Abstract

Behavioral inhibition (BI) and maternal over-control are early risk factors for later childhood internalizing problems, particularly social anxiety disorder (SAD). Consistently high BI across childhood appears to confer risk for the onset of SAD by adolescence. However, no prior studies have prospectively examined observed maternal over-control as a risk factor for adolescent social anxiety (SA) among children initially selected for BI. The present prospective longitudinal study examines the direct and indirect relations between these early risk factors and adolescent SA symptoms and SAD, using a multi-method approach. The sample consisted of 176 participants initially recruited as infants and assessed for temperamental reactivity to novel stimuli at age 4 months. BI was measured via observations and parent-report across multiple assessments between the ages of 14 months and 7 years. Maternal over-control was assessed observationally during parent-child interaction tasks at 7 years. Adolescents (ages 14–17 years) and parents provided independent reports of adolescent SA symptoms. Results indicated that higher maternal over-control at 7 years predicted higher SA symptoms and lifetime rates of SAD during adolescence. Additionally, there was a significant interaction between consistently high BI and maternal over-control, such that patterns of consistently high BI predicted higher adolescent SA symptoms in the presence of high maternal over-control. High BI across childhood was not significantly associated with adolescent SA symptoms when children experienced low maternal over-control. These findings have the potential to inform early interventions by indentifying particularly at-risk youth and specific targets of treatment.

Keywords: Behavioral inhibition, parenting, maternal over-control, social anxiety

In early childhood, behavioral inhibition (BI) refers to a biologically-based temperamental style in which young children consistently respond to unfamiliar situations, objects, and people with negative emotion and withdrawal (Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, 2005; Kagan, 1997). BI is typically measured in the laboratory by observing young children’s reactivity to novel stimuli, including non-social and social stimuli (e.g., unfamiliar room, mechanical robot, adult stranger; Fox, Henderson, Rubin, Calkins, & Schmidt, 2001; Kagan, Reznick, & Snidman, 1987). While younger children usually display BI across a range of novel contexts, older children tend to display BI more clearly in novel social contexts. Earlier measures of infant reactivity and toddler BI are understood to be antecedents of later childhood BI in social contexts (Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009).

Across studies, the terms “shyness,” “social withdrawal,” and “social reticence” are commonly used to describe children’s display of fear, wariness, and avoidance in response to social novelty (Rubin et al., 2009). These terms collectively describe children who consistently remain on the outskirts of novel social situations, appearing self-conscious around unfamiliar adults and peers, quietly watching others from a distance rather than actively participating, despite having the desire to approach or join the social interaction (Degnan, Henderson, Fox, & Rubin, 2008; Rubin et al., 2009). Thus, hereafter we use the term BI to signify the consistent tendency across childhood to react to novel situations with negative emotion and withdrawal.

Approximately 15 to 20% of children display BI early in life, as assessed in laboratory paradigms (Fox et al., 2005). Several longitudinal studies report continuity estimates of BI ranging from .18 to .52 across early childhood, with continuity referring to consistency in the expression of BI in groups of children over time (Bornstein, Brown, & Slater, 1996; Degnan & Fox, 2007). Moderate continuity of BI across early childhood has been found among samples initially selected for temperamental reactivity/BI in toddlerhood (r = .52), whereas less continuity from toddlerhood across early childhood has been observed among unselected samples (r = .26; Degnan & Fox, 2007). Variation in continuity may reflect differences in sample composition, assessment methods, and study design.

Past research suggests that BI is associated with increased risk for the development of anxiety, though there has been considerable variability across studies in the measurement of these constructs. In a recent study, preschoolers selected for parent-reported BI were classified as high BI based on a laboratory observation of their reactions to novel stimuli. High BI preschoolers had a greater likelihood of meeting diagnostic criteria for concurrent anxiety disorders than low BI preschoolers (Hudson, Dodd, & Bovopoulous, 2011), as well as social anxiety disorder (SAD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) two years later (Hudson, Dodd, Lyneham, & Bovopoulous, 2011). Similarly, Biederman and colleagues (2001) reported that BI, assessed observationally once between the ages of 2–6 years, was specifically associated with concurrent SAD among children at familial risk for anxiety, and predicted the onset of SAD over a 5-year follow-up period (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2007). Another study reported that children high in BI who were initially recruited based on parent-report of BI, and then assessed comprehensively for BI at ages 5–8 years, evidenced increased parent-reported social anxiety (SA) symptoms at ages 8–11 (Muris, van Brakel, Arntz, & Schouten, 2011).

At least four longitudinal studies have examined BI as a risk factor for adolescent psychological disorders. In a sample assessed for BI at age two years, Schwartz and colleagues (1999) reported that 34% of adolescents with histories of high BI had lifetime SAD by age 13, relative to 9% classified as low BI. In a large normative sample followed from infancy, Prior et al. (2000) reported that 42% of children classified as high BI had anxiety problems at age 13–14 years (i.e., the highest 15% of parent- and child-reported anxiety scores), compared to 11% never classified as high BI. Importantly, “high BI” was defined as high BI across 6 out of 8 study assessments.

In another community sample, Essex and colleagues (2010) reported greater rates of lifetime SAD among 14-year-olds initially assessed from a home observation of BI at age 4.5 years, and then assessed biennially for continued BI via parent-, teacher-, and child-report. Results indicated that 50% of children who exhibited chronic high BI had a lifetime diagnosis of SAD by age 14 years, compared to none in the chronic low group. Similarly, Chronis-Tuscano et al. (2009) reported that 20% of adolescents (aged 14–17 years) with histories of consistently high maternal-reported BI across childhood, met criteria for lifetime SAD, relative to 11.2% of adolescents with histories of low BI. Taken together, these studies strongly suggest that BI is associated with increased risk for later anxiety, with mounting empirical support for a specific link to SAD. Further, these studies suggest that children who show high BI consistently across childhood face particularly high risk for later SAD (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Essex et al., 2010; Prior et al., 2000). Thus, the importance of measuring BI at multiple time points across childhood has recently been emphasized in this literature.

Despite the greater risk of anxiety associated with high BI, only a small portion of adolescents who develop anxiety disorders have histories of high BI across childhood (Degnan & Fox, 2007). Indeed, Prior et al. (2000) reported that only 21.4% of adolescents with anxiety problems had a history of consistent high BI, compared to 11% of non-anxious adolescents. Although high BI is one of the most consistent individual level risk factors for later anxiety that can be identified in early childhood (Fox et al., 2005), the association between childhood BI and later anxiety still shows almost as much disassociation as it shows association across time (Degnan & Fox, 2007). Though several studies have found direct associations between childhood BI and adolescent anxiety, these are typically modest effects (Degnan & Fox, 2007), and one past study failed to find this association at all (Caspi, Moffitt, Newman, & Silva, 1996). Also, indirect rather than direct effects are often found, in which childhood BI predicts adolescent SA only in the presence of cognitive moderators (e.g., Perez-Edgar, Bar-Haim, et al., 2010; Perez-Edgar, McDermott, et al., 2010; Reeb-Sutherland et al., 2009). Thus, it is important to examine potential moderators of this association (Degnan, Almas, & Fox, 2010).

Parenting likely plays a critical role in whether children who exhibit BI across childhood develop later SAD (Rapee, 1997). In particular, the parenting dimensions referred to in the literature as “parental over-control”, “intrusiveness”, “overinvolved/overprotective”, or “oversolicitousness” have been associated with childhood and adolescent SA (McLeod, Wood, & Weisz, 2007; Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang, & Chu, 2003). Compared to other parenting behaviors, maternal over-control has been fairly consistently associated with anxiety generally, and with SA specifically. A recent meta-analysis reported a medium effect size (d = .58) for the association between observed maternal over-control and childhood anxiety, and a larger effect size (d = .76) for childhood social anxiety (van der Bruggen, Stams, & Bogels, 2008).

Rubin and colleagues have proposed a developmental theory to explain how early BI increases risk for later SAD (Rubin, Hymel, Mills, & Rose-Krasnor, 1991). This theory posits that, for some parent-child dyads, there is a reciprocal relation between BI and parenting, in which parents perceive their inhibited children as highly vulnerable, due to the negative emotion and withdrawal these children exhibit in novel situations, particularly in novel social situations as children get older (Mills & Rubin, 1990; 1993). Accordingly, in order to reduce child distress, some parents engage in overly protective, directive, and controlling behaviors, even when the situation does not require such behavior (Rubin, Nelson, Hastings, & Asendorpf, 1999). In turn, their children become increasingly reliant on adults, internalizing the belief that they will not be able to successfully cope with anxiety-provoking situations on their own (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). Thus, maternal over-control may increase risk for later SA when parents behave in ways that limit their children’s exposure to and independent coping with novel social situations (Rapee, 1997). As such, maternal over-control may be viewed as moderating the link between BI and later SA (Rubin et al., 2009). That is, children with both early risk factors may be at greater risk for SAD than those low in BI or those whose mothers are less controlling.

Indeed, a recent study suggests that observed maternal over-control longitudinally predicts later SAD and GAD among 6-year-olds assessed for BI as preschoolers (Hudson, Dodd, Lyneham, et al., 2011). Previous studies conducted with community samples indicate that maternal over-control predicts later internalizing symptoms, based on ratings by multiple informants and direct laboratory observations (Bayer, Hastings, Sansom, Ukoumunne, & Rubin, 2010; Bayer, Sanson, & Hemphill, 2006; Edwards, Rapee, & Kennedy, 2010). Two of these studies employed observational tasks to measure maternal over-control (Bayer et al., 2006; Hudson, Dodd, Lyneham, et al., 2011), whereas the others relied on parenting questionnaires (Bayer et al., 2010; Edwards et al., 2010). Additionally, maternal over-control has been found to moderate the association between BI and later internalizing problems during early childhood (Coplan, Arbeau, Armer, 2008; Feng, Shaw, & Moilanen, 2011; Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002) and into middle childhood (Degnan et al., 2008; Hane, Cheah, Rubin, & Fox, 2008). Throughout all of this work, no studies have prospectively examined the role of maternal over-control, assessed observationally, in predicting SAD in adolescence, the developmental period during which the onset of SAD peaks (Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brook, & Ma, 1998).

The present study extends the prior research literature in several critical ways. We followed participants prospectively, from infancy through adolescence, across approximately 14 years of development. We measured BI comprehensively, through behavioral observation and parent-report across multiple childhood assessments. Importantly, we measured maternal over-control observationally, rather than by parent report or retrospective report. Further, we utilized multiple informants to assess SA in adolescence. To our knowledge, this is the only prospective longitudinal study to examine the interaction between a multi-method measure of BI and observed maternal over-control in predicting adolescent SA. Based on past research, we predicted that consistently high BI and maternal over-control would both individually predict higher adolescent SA symptoms. We additionally predicted that maternal over-control would moderate the association between consistently high BI and adolescent SA symptoms, such that SA symptoms would be highest among adolescents with histories of both early risk factors.

Method

Participants

The sample was drawn from a longitudinal study examining temperament and social behavior across the lifespan (e.g., Calkins, Fox, & Marshall, 1996; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Fox et al., 2001; Kagan et al., 1987). Initial recruitment procedures for the larger study involved sending mailings to families from the birth records of local hospitals, asking that parents return a survey to ensure that infants met study inclusion criteria. Of families who returned the initial survey, those who indicated that infants were born full-term, normally developing, and had parents who were right-handed (to address aims of the larger study) were invited to attend a laboratory assessment of infants’ reactivity to novel auditory and visual stimuli (see Kagan et al 1987 and Calkins et al 1996 for a description of this paradigm) at the University of (This should University of Maryland) (N = 443). Based on this assessment, 176 infants were selected and followed into adolescence.

Participants were included (n =176; 89 female, 87 male) in the present study if they provided data on at least one of the measures, including BI, maternal over-control, or SA symptoms. Of the sample selected, 66 (37.5%) had complete data on all measures of BI, maternal over-control, and SA symptoms. Of the final sample of 176, 35% of infants showed high negative/high motor reactivity to novel stimuli, 31% showed high positive/high motor reactivity to novel stimuli, and 34% showed low reactivity to novel stimuli at the 4-month assessment. All participants were European-American and initially from two-parent, middle-to-upper class families. Most mothers had graduated from high school (28%) or college (49%), with the remainder having completed graduate school (11%) or listed their educational attainment as “other” (12%).

Of the original selected sample, 165 provided BI data either observationally and/or via maternal report at some point across childhood (at 14 months, 24 months, 4 years, and 7 years), 81 completed the parenting observation at the 7-year assessment, and 137 provided SA data as adolescents (age range: 14 – 17 years; M = 15.05, SD = 1.82). Missing data patterns across these measures (including child gender, parent education, and 4-month reactivity) did not violate the assumption that they were missing completely at random (MCAR; Little & Rubin, 1987), Little’s MCAR χ2 = 11.79, p = .11. Therefore, data were analyzed in Mplus 6.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 2011) using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) in order to use all available data points.

Measures

Behavioral inhibition.

At 14 and 24 months, infants’ reactions to novel stimuli in the laboratory were coded to provide an index of BI (see Calkins et al., 1996, Fox et al., 2001, and Kagan et al., 1987, for a complete description of these procedures). At 14 months, the novel stimuli consisted of: (1) an unfamiliar room; (2) a mechanical robot; and (3) an adult stranger. At 24 months, the stimuli were identical and, additionally, children were asked to crawl through an inflatable tunnel. A composite index of BI at each age was computed by summing standardized reaction scores to these novel stimuli, with higher scores indicating greater BI. Specifically, child behavior was coded in seconds for latency to touch a toy or approach the stranger, latency to vocalize, and proportion of time spent in proximity to mother. At 14 months, inter-rater reliability was computed for 15% of the sample and Pearson correlations ranged from 0.85 to 1.00. At 24 months, inter-rater reliability was computed for 24% of the sample and Pearson correlations ranged from 0.77 to 0.97.

Maternal ratings of temperament at 14 and 24 months were gathered using the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ; Goldsmith, 1996), an 111-item measure on which mothers rated the frequency of specific behaviors as they occurred in the past month. For this study, the Social Fearfulness scale, which consists of 19 items (α = .87) measuring inhibition, distress, withdrawal, and shyness, was utilized as a measure of BI, with higher scores indicating greater BI. For instance, items included: “When s/he saw other children while in the park or playground, how often did your child approach and immediately join in play?”; “When one of the parents’ friends who does not have daily contact with your child visited the home, how often did your child talk much less than usual?”; “When your child was approached by a stranger when you and she/he were out, how often did your child show distress or cry?”

At 4 and 7 years of age, children were observed in same-age, same-sex quartet playgroups to assess their reactions to unfamiliar peers. Each playgroup consisted of one child who exhibited high BI in the laboratory at the previous visit (one-half standard deviation or more above the mean), one child who exhibited very low BI in the previous laboratory visit (one-half standard deviation or more below the mean), and two average children (within one standard deviation of the mean). Data for this study were taken from the free-play session, during which the children were left alone in the playroom for 15 minutes with age-appropriate toys, while their mothers remained in a waiting area.

Child behaviors fitting two categories from the Play Observation Scale (POS; Rubin, 2001) were coded from the 15-minute free-play session in 10-second segments: Onlooking behavior, defined as “the child observes the other children’s activities without attempting to play,” and Unoccupied behavior, defined as “the child demonstrates an absence of focus or intent” (see Fox et al., 2001 for additional details). The sum of these two behaviors was divided by the total number of observed segments minus the number of un-codable segments to create the proportion of time spent displaying BI, with higher scores indicating a greater proportion of BI observed. Three independent coders double-coded 30% of the cases at each age, yielding Cohen’s kappas ranging from 0.71 to 0.86 at age four and 0.84 to 0.88 at age seven.

At 4 and 7 years, mothers completed the Colorado Children’s Temperament Inventory (CCTI; Buss & Plomin, 1984; Rowe & Plomin, 1977). The Shyness/Sociability subscale of the CCTI was used for the present study. In prior research, this subscale has been associated with observed BI and shyness (e.g., Emde et al., 1992). It includes 5 items rated from 1–5, such as “child tends to be shy” or “child takes a long time to warm up to strangers,” (α = .88), with higher scores indicating greater BI.

Longitudinal BI profiles.

To create a comprehensive, single BI variable incorporating all of the eight measures of BI collected across the four study time points, continuous BI profiles were created using Latent Class Analysis (LCA) performed in Mplus. This analysis yielded a measure of each child’s probability score of belonging to a high BI profile. While variable-oriented approaches like correlation examine associations between measures, LCA is a person-oriented analysis that seeks to identify unmeasured (i.e., latent) class membership among participants using observed indicator variables in a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework (see Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009, for a more detailed description of this analysis).

The LCA included continuous measures of observed BI and maternal report of BI at the four study assessments (i.e., a total of 8 measures), to estimate BI class membership. To account for our use of different BI measures over time, a sub-type of LCA, Latent Profile Analysis (LPA; Gibson, 1959), was performed, which estimates the average level of BI at each age independently within each class or profile. Models with 2 through 4 profiles were estimated. Best model fit was assessed using Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), where the smallest negative number indicates best fit. This index has been shown to identify the appropriate number of groups in finite mixture models and penalizes the model for the number of parameters, thus guarding against models over fitting the data. The Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood ratio test (LMRL) was also used, which tests the significance of the −2 Log likelihood difference between models with k and k-1 profiles (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001).

The LPA was computed using all 165 participants who provided BI data at any of the assessments, as the data did not violate missing data assumptions, Little’s MCAR χ2 (180) = 192.86, p = .24. Model fit (BIC) for the current analysis was 2861.29 for one profile, 2737.55 for two profiles, 2722.96 for three profiles, and 2701.36 for four profiles. The LMRL showed that the 2-profile model was significantly better than the 1-profile model (p < .05); however, the 3-profile model was not significantly better than the 2-profile model (p > .05), nor was the 4-profile model significantly better than the 3-profile model (p > .05). Given that a low BIC and a significant LMRL occurred for the 2-profile model, this was chosen as the best-fitting model.

The high BI profile represented high average levels of BI at all four study time points and 15% of the sample (n = 25) had a higher probability of membership in this profile than the other profile. The “low” profile represented lower levels of BI at all four time points and 85% of the sample (n = 140) had a higher probability of membership in this profile than the other profile. In the current study, the continuous individual probabilities of membership in the high BI profile were used as the consistently high BI variable in all subsequent analyses (M = 0.16, SD = 0.33; range = 0–1; skewness = 1.94).

Maternal over-control.

Three parent-child interaction tasks were conducted at the 7-year assessment. These included an unstructured free play session, a toy clean-up, and an origami paper-folding task (Hane et al., 2008). Quality of maternal behavior was coded following the guidelines developed by Rubin and Cheah (2000). Maternal behaviors were rated on five scales: (1) hostile affect; (2) negative affect; (3) over-control; (4) positive control; and (5) guidance. A portion of the videotaped interactions (20%) were double-coded by independent raters who were blind to study hypotheses. Adequate inter-rater reliability was attained across scales, with inter-rater reliability correlations ranging from 0.81 to 0.93. Given previously reviewed findings, the maternal over-control scale was of primary interest.

Maternal over-control was defined as ill-timed, excessive, and inappropriately controlling maternal behaviors, relative to the child’s behavior, interests, and desires (Rubin & Cheah, 2000). Ratings of maternal over-control were assigned for each minute of the parent-child interaction on a 3-point scale, in which a score of 1 indicated “none” (i.e., no instances of maternal over-control observed); a score of 2 indicated “moderate over-control” (i.e., mother verbally dominates the conversation or the play activity, directing the child’s attention away from his/her interests and/or excluding the child from participation); and a score of 3 indicated “outright over-control” (i.e., frequent unnecessary and restrictive instructions and/or physically controlling behaviors that change or stop the child’s play). For example, maternal behaviors receiving a “3” in this domain would include parents frequently issuing unnecessary commands/instructions, interrupting the child, physically moving the child away from his/her interests, grabbing a toy from the child, or restricting the child’s access to a desired toy. These scores were then summed and divided by the total number of one-minute scores to create an average maternal over-control score for each of the three tasks (Hane et al., 2008). Average scores were then standardized to account for variability in the length of these tasks. Z-scores were summed to create a maternal over-control variable, with higher scores indicating greater maternal over-control.

Social anxiety.

At the adolescent assessment, participants and their parents independently completed the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1999). The SCARED is a psychometrically-sound measure of child and adolescent anxiety symptoms. Due to prior evidence of consistently high BI and maternal over-control as specific risk factors for later SAD, the Social Phobia scales of the adolescent- and parent-report versions of the SCARED (SCARED-SP) were the dependent variables of interest. The parent and adolescent versions of the SCARED-SP scale include the same 7 items rated on a 3-point scale (0 = not true/hardly ever true, 1 = somewhat/sometimes true, and 2 = very true/very often true). For example, items include, “it is hard for me (or, “my child”) to talk with people I don’t (or, “my child doesn’t”) know well” or “I feel nervous when I am with other children or adults and I have to do something while they watch me like read aloud, speak, play a game, or play a sport” or “I feel nervous when I am going to parties, dances, or any place where there will be people I don’t know well.” Higher scores on this scale indicated greater SA symptoms.

To assess lifetime diagnoses of SAD, 133 (97%) of the 137 adolescents with SCARED data, and their parents, were separately administered the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Kaufman et al., 1997). The K-SADS-PL was supplemented with additional probe questions from the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (Silverman & Albano, 1996; see Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009 for more detail). Interviews were conducted by advanced clinical psychology doctoral students under the close supervision of a licensed clinical psychologist and a board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist, all of whom were blind to early temperament and maternal over-control data as well as questionnaire data. Audiotapes of 59 interviews (44%) were reviewed for reliability, and agreement between interviewers and expert clinicians was high for anxiety diagnoses (κ = .92).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the main study variables. Table 2 presents intercorrelations between the predictor variables. The majority (89%) of observed and parent-reported measures of BI were significantly positively correlated, ranging from 0.23 to 0.74, p’s < .05. Additionally, correlations between the BI continuous probability measure used in all following analyses and each individual measure of BI were all positive and significant, ranging from 0.25 to 0.71 (M = .49; p’s < .05). None of the measures of BI were significantly correlated with maternal over-control, p’s > .05. There were no gender differences in BI or SA symptoms, p’s > .05; thus, child gender was not included in our main analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics on Main Study Variables for the Total Sample

| Measure | N | % of data | Min | Max | M | SD | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed BI | |||||||

| 14 Months | 142 | 80.1% | −8.90 | 16.75 | 0.00 | 5.07 | 1.08 |

| 24 Months | 150 | 85.2% | −8.07 | 11.52 | 0.00 | 4.32 | 0.44 |

| 4 Years | 137 | 77.8% | 0.00 | 0.87 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 1.98 |

| 7 Years | 115 | 65.3% | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 2.95 |

| Parent-reported BI | |||||||

| 14 Months | 139 | 79.0% | 1.63 | 6.40 | 3.88 | 0.83 | .30 |

| 24 Months | 133 | 75.6% | 2.00 | 6.21 | 4.09 | 0.95 | .28 |

| 4 Years | 133 | 75.6% | 1.00 | 4.80 | 2.54 | 0.84 | .35 |

| 7 Years | 116 | 65.9% | 1.00 | 4.00 | 2.24 | 0.76 | .35 |

| Maternal Over-Control | 81 | 46.0% | −0.94 | 2.55 | −0.04 | 0.66 | 1.21 |

| SCARED-Social Phobia | |||||||

| Adolescent-report | 122 | 69.3% | 0.00 | 13.00 | 3.84 | 3.35 | .59 |

| Parent-report | 122 | 69.3% | 0.00 | 14.00 | 3.91 | 3.68 | .85 |

Note. BI = Behavioral Inhibition

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations Between Study Predictor Variables

| 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Observed BI – 14 mon. | .40*** n = 131 |

.26*** n = 120 |

.15 n = 103 |

.22** n = 133 |

.36*** n = 118 |

.23* n = 119 |

.23* n = 103 |

.11 n = 70 |

.02 n = 98 |

.09 n = 97 |

| 2. Observed BI – 24 mon. | -- | .36*** n = 130 |

.23* n = 108 |

.19* n = 130 |

.37*** n = 131 |

.28** n = 126 |

.32** n = 108 |

−.17 n = 74 |

.06 n = 105 |

.02 n = 104 |

| 3. Observed BI – 4 years | -- | .30** n = 111 |

.36*** n = 120 |

.34*** n = 117 |

.48*** n = 133 |

.42*** n = 112 |

.04 n = 77 |

−.04 n = 99 |

.06 n = 99 |

|

| 4. Observed BI – 7 years | -- | .03 n = 102 |

.07 n = 100 |

.32*** n = 109 |

.32** n = 107 |

−.17 n = 75 |

.18 n = 87 |

.09 n = 89 |

||

| 5. Parent-report BI – 14 mon. | -- | .36*** n = 118 |

.23* n = 119 |

.30** n = 103 |

.07 n = 69 |

−.05 n = 99 |

−.04 n = 98 |

|||

| 6. Parent-report BI – 24 mon. | -- | .35*** n = 114 |

.41*** n = 102 |

.12 n = 70 |

.13 n = 96 |

.20 n = 93 |

||||

| 7. Parent-report BI – 4 years | -- | .74*** n = 109 |

.05 n = 75 |

.17 n = 96 |

.31** n = 96 |

|||||

| 8. Parent-report BI – 7 years | -- | .03 n = 78 |

.19 n = 87 |

.38*** n = 86 |

||||||

| 9. Observed Maternal Over-control | -- | .20 n = 61 |

.29* n = 57 |

|||||||

| 10. Adolescent-report SCARED-SP | -- | .48*** n = 107 |

||||||||

| 11. Parent-report SCARED-SP | -- |

Note. BI = Behavioral Inhibition. SCARED-SP = SCARED Social Phobia scale.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Additionally, bivariate correlations revealed that the adolescent- and parent-reported SCARED-SP scores were moderately correlated, r = .48, p < .001. Thus, the scores were averaged in order to simplify the results. However, the results held when either the adolescent- or parent-report SCARED-SP scale was included as the dependent variable. Of the 133 adolescents assessed with the K-SADS-PL, 26 (19.5%) met diagnostic criteria for lifetime SAD. SCARED-SP scores were significantly higher for adolescents with SAD than for those who were not diagnosed with SAD (NSAD), Adolescent-report: t (114) = −4.37, p = .00 (MSAD=6.48, SDSAD=3.38; MNSAD=3.31, SDNSAD=3.05); Parent-report: t (26.52) = −6.97, p = .00 (MSAD=8.04, SDSAD=4.34; MNSAD=2.98, SDNSAD=2.74). Overall, the averaged SCARED-SP scores ranged from 0–14 (skewness = .57). Thus, the SCARED-SP scores were normally distributed, despite the inclusion of adolescents with SAD in the sample.

Predicting Adolescent Social Anxiety

In order to test whether BI, maternal over-control, or the interaction of the two would predict SA symptoms in adolescence, a linear regression was conducted in an SEM framework with MLE for all participants with data on one or more variables using Mplus 6.1 (N = 176; Muthen & Muthen, 2011). An additional logistic regression was conducted in order to examine lifetime SAD in adolescence as the dependent variable. This analysis estimates the log likelihood of each model for the outcome (e.g., SA symptoms), conditional on the covariates (e.g., BI, maternal over-control, BI x maternal over-control). Similar to traditional regression analysis, all covariates were assumed to be correlated. Means and variances of all continuous covariates were estimated in the model to allow for missing data among these measures. Prior to all regression analyses, continuous covariates were mean-centered and the interaction of the predictors was computed as the product of the two mean-centered variables.

The effects of BI, maternal over-control, and the interaction of the two on SA symptoms are presented in Table 3. Overall, the linear regression analysis predicting SA symptoms provided good fit to the data, χ2 = 0.00, p = .99; RMSEA = 0.00; CFI = 1.00, TFI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.00, and it showed significant improvement over a model with zero-level effects, Δ χ2 (3) = 12.65, p < .01. Results of the model revealed a main effect of maternal over-control, such that higher maternal over-control at age 7 was associated with higher adolescent SA symptoms, p = .00. In addition, the interaction between consistently high BI and maternal over-control was a significant predictor of adolescent SA symptoms, p = .02.

Table 3.

Predicting Adolescent Social Anxiety from Consistently High BI and Maternal Over-Control

| Social Anxiety Symptoms (SCARED-SP Scale; N = 176) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | |

| BI | 0.36 | 0.99 | 0.04 |

| Over-Control | 1.70 | 0.55 | 0.35** |

| BI x Over-Control | 5.15 | 2.24 | 0.29* |

| Total R2 | .16* | ||

| Lifetime Social Anxiety Disorder (KSADS-PL; N = 175) | |||

| B | SE B | β | |

| BI | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.12 |

| Over-Control | 0.55 | 0.20 | 0.36** |

| BI x Over-Control | 1.14 | 0.60 | 0.20t |

| Total R2 | .16t | ||

Note: BI = Behavioral Inhibition

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01

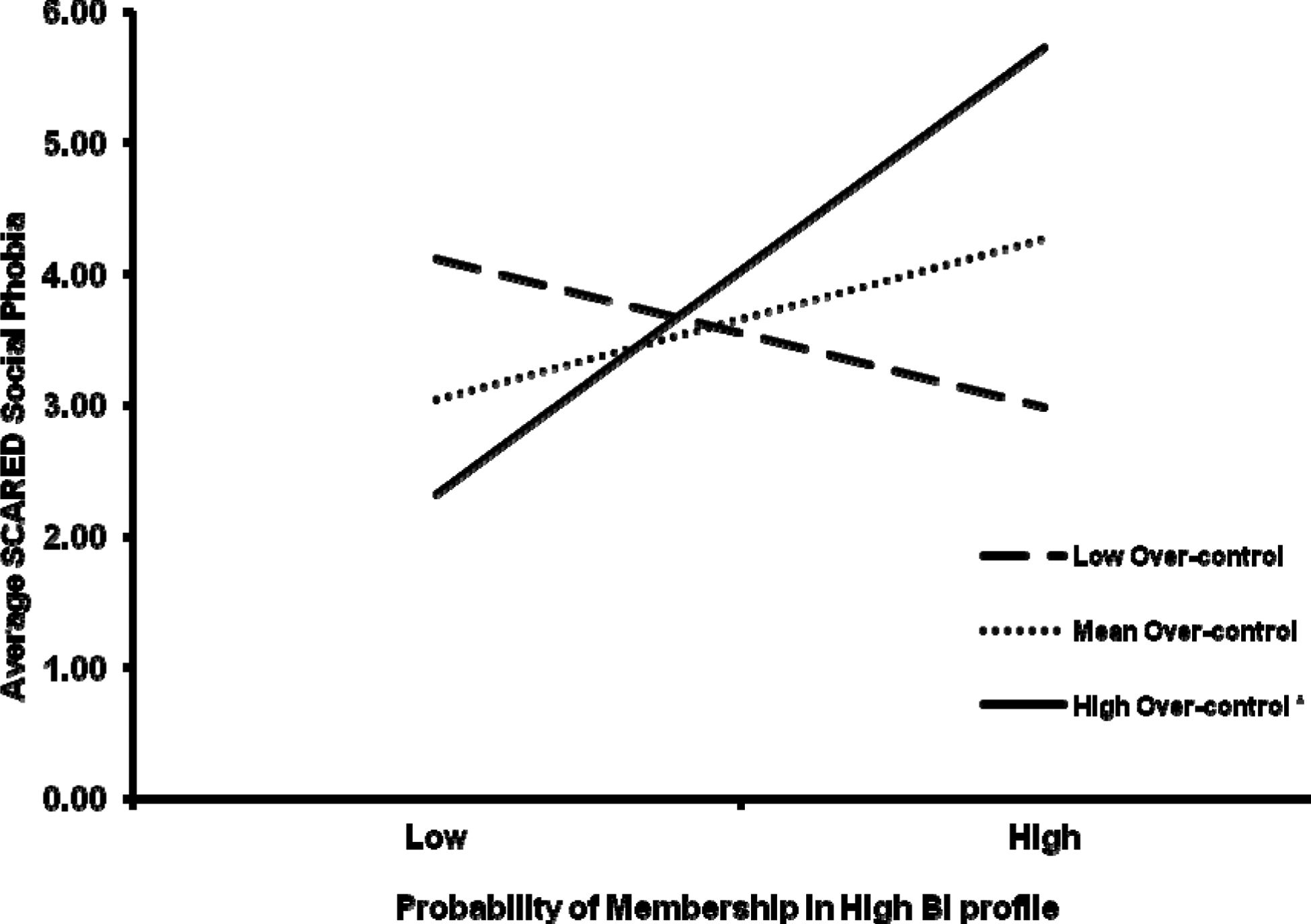

As recommended by Aiken and West (1991), to examine the two-way interaction, the effect of consistently high BI on SA symptoms was examined when maternal over-control was low (−1 sd) and high (+1 sd). When maternal over-control was low, consistently high BI was not significantly related to adolescent SA symptoms, p = .16. However, in the presence of high maternal over-control, consistently high BI was positively related to adolescent SA symptoms, p = .01. In other words, greater probability of following the high BI profile over time was associated with greater adolescent SA symptoms for those who experienced high maternal over-control (see Figure 1). High BI across childhood was not associated with adolescent SA symptoms for those who experienced low maternal over-control.

Figure 1.

Interaction between consistently high BI and maternal over-control predicting adolescent social anxiety symptoms.

The effects of BI, maternal over-control, and the interaction of the two on lifetime SAD are presented in Table 3. Overall, the logistic regression analysis provided good fit to the data, CFI = 1.00, TFI = 1.00; WRMR = 0.00. Results of the model revealed a main effect of maternal over-control, such that higher maternal over-control was associated with a greater likelihood of adolescent SAD diagnosis, p = .01. However, the interaction between the two predictors was significant only at trend level, p = .06, and was therefore not probed any further.

Discussion

In the present study, childhood risk factors for adolescent SA were examined in a longitudinal research design. This study extends prior research in this area by incorporating multiple observational and maternal-report assessments of BI across childhood, prospectively examining the influence of observed maternal over-control on adolescent SA, and examining the moderating role of observed maternal over-control on the association between childhood BI and adolescent SA symptoms. The results supported our hypothesis that higher maternal over-control at age seven years would predict higher SA symptoms, as well as lifetime rates of SAD, in adolescence. Additionally, our prediction that maternal over-control would moderate the association between consistently high BI and adolescent SA symptoms was also supported. Specifically, maternal-control was positively associated with adolescent SA symptoms among adolescents who had histories of high BI across childhood, but not among those who had histories of lower BI across childhood. However, contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find evidence of a main effect of consistently high BI on adolescent SA symptoms.

Our results are consistent with prior research suggesting that maternal over-control is an important risk factor for later SAD (van der Bruggen et al., 2008), though our study extends results of prior work by following children prospectively into adolescence and by utilizing an observational measure of maternal over-control, which is considered the exemplary method of assessing parenting behaviors (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2008). To our knowledge, this is also the very first study to report a significant interaction between consistently high BI and maternal over-control as related to SA symptoms in adolescence. Consistent with developmental theory (Rubin et al., 1991), our results suggest that young children who exhibit high BI across early childhood are at-risk for later SA when their mothers behave in overly controlling ways.

Consistent with our previously reported finding on this sample (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009), there was no main effect of consistently high BI on adolescent SA symptoms when the BI profiles included behavioral observations and maternal reports of BI. Specifically, Chronis-Tuscano et al. (2009) reported that the predictive link between childhood BI and adolescent SAD only held when BI was based solely on maternal-report, and not when it was based on behavioral observation or on composites derived from both maternal-report and behavioral observation. Similarly, in past studies reporting direct effects of childhood BI on adolescent SA, the multiple assessments of BI across childhood were based solely on maternal-report (Prior et al., 2000), or on parent-, child-, and teacher-report (Essex et al., 2010), rather than the observational measures incorporated into our measure of BI. We chose to conceptualize BI as a continuous variable based on multiple observations and maternal-ratings of BI over time in order to yield the most reliable and valid measure of BI, and to lessen the possibility that our findings would be an artifact of shared-method variance. Additionally, though there has been empirical support for a direct and specific association between childhood BI and adolescent SA, not all past studies have reported this association (Caspi et al., 1996) and many have reported indirect, rather than direct, effects of childhood BI on adolescent anxiety (e.g., Reeb-Sutherland et al., 2009).

Recent studies suggest that it may be critical to differentiate subtypes of children among those who show consistently high BI in childhood. For example, one recent study reported that preschool social BI was concurrently associated with parent-reported shyness, inhibition with peers, adults, and in performance situations, as well as the SA and separation anxiety scales of a preschool diagnostic interview; whereas preschool non-social BI was concurrently associated with parent-reported fear and the specific phobia scale on a preschool diagnostic interview (Dyson, Klein, Olino, Dougherty, & Durbin, 2011). Further, recent work by Buss (2011) suggests that toddlers who exhibit fear and withdrawal in both low-threat contexts (i.e., situations that most toddlers find enjoyable and do not show significant wariness) and high-threat contexts (i.e., situations in which most toddlers exhibit fear and engage in avoidance) are at greatest risk for later internalizing problems and anxiety, compared to toddlers who exhibit increasing fear and avoidance as situations increase in the level of threat (Luebe, Kiel, & Buss, 2011). Similarly, Gazelle (2008) identified distinct subtypes of 3rd grade children who showed “anxious-withdrawal,” similar to our definition of BI in the present study, and found different developmental trajectories of peer rejection and victimization based on subtype membership among children exhibiting anxious-withdrawal. As collectively suggested by these studies, the construct of BI may require greater differentiation in order to yield the greatest specificity in predicting later psychopathology.

Although the present study included several methodological strengths, it is important to interpret our results in light of study limitations. As in any longitudinal study, there was a substantial proportion of missing data, particularly for the parenting observation at the 7-year assessment. However, we utilized statistical methods well-equipped to handle missing data, and there was no evidence of selective attrition. Our sample was predominantly comprised of European-American, middle-class participants, which limits the generalizability of our findings to more diverse cultural groups. The sample was also initially recruited and followed based on infants’ reactivity to novel stimuli, which provided a wider range of temperamental reactivity in the current sample than would be observed in a random community sample. It is therefore unclear whether our findings would remain the same in unselected community samples.

Further, we examined only one dimension of parenting at a single time point through observed parent-child interaction tasks. Though observation is largely regarded as superior to relying on maternal- or retrospective-report of parental behaviors, we cannot rule out the notion that maternal behavior may have been influenced by the artificial nature of the laboratory tasks. Moreover, we failed to measure other potentially important predictors of adolescent SA, including parental psychopathology. A recent meta-analysis suggests much greater risk of anxiety and depressive disorders among offspring of anxious parents (Micco et al., 2009). It may be that anxious parents more often engage in overly controlling behaviors, and thus, maternal over-control may mediate the association between parent and child anxiety. Future studies are therefore needed to further tease apart the complex interplay of associations between childhood BI, parental psychopathology, parental over-control, and adolescent SA.

Future studies should continue to build on the findings reported here, by incorporating multiple methods and assessments of BI and maternal over-control across childhood in predicting adolescent psychopathology. These might include measures of not only BI, but also temperamental exuberance, as well as other observed parenting dimensions in addition to maternal over-control. Future studies might also examine over-control observed in distinct contexts (e.g., play vs. anxiety-provoking situations) to better understand the circumstances under which this dimension of parenting is most predictive of later SA.

Despite the limitations inherent in the present study, our results clearly indicate that maternal over-control is an important predictor of later SA symptoms and diagnoses, particularly among adolescents who exhibited consistently high patterns of BI across childhood. This research offers practical implications for who, when, and what intervention programs should target in order to prevent the development of SAD.

Clinical Implications

Our results provide important clinical information regarding which children should be targeted by prevention or early intervention programs, namely, children whose parents report a history of consistently high BI from toddlerhood across early childhood. Parenting programs aimed at reducing maternal over-control may place such children on healthier social trajectories, thereby preventing the development of adolescent SAD, which has been linked to continued anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders in young adulthood (Pine et al., 1998; Tull, Baruch, Duplinksy, & Lejuez, 2008).

Regarding specific targets for early interventions, though there is evidence that parental involvement is less essential in cognitive-behavioral treatment for older children and adolescents with anxiety disorders (M = 9.9 years, SD = 2.8; Silverman, Kurtines, Jaccard, & Pina, 2009), our results along with findings from a recent randomized clinical trial (RCT) of a parenting intervention for anxious preschoolers (Hirshfeld-Becker et al., 2010), highlight the importance of modifying parent behaviors when treating young children with anxiety. Indeed, results from a recent RCT testing a 6-session parenting intervention for preschoolers with high BI, Rapee and colleagues (2010) found that child anxiety disorders were effectively treated by the intervention, but high BI was not altered over the course of treatment. That is, the parenting intervention did not change children’s underlying temperament, but was associated with the remission of anxiety disorders (i.e., a reduction in the impairment associated with high BI). These findings suggest the importance of targeting maternal behaviors when treating young children with high BI.

Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT; Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008) is an evidence-based treatment (EBT) that teaches parents strategies to follow children’s lead in play through therapists providing in-vivo coaching of specific skills (i.e., Child Directed Interaction skills). That is, as one intervention component, parents are taught skills on the opposite end of the continuum of those comprising our measure of maternal over-control. While PCIT is a well-established treatment for preschoolers with disruptive behavior disorders (Eyberg et al., 2008), studies examining the efficacy of PCIT in treating separation anxiety have also yielded promising results (Chase & Eyberg, 2008). Additional studies testing PCIT and/or other EBTs focused on reducing maternal over-control to prevent the emergence of SAD among children with histories of consistently high BI appear warranted.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01MH07454 and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R37HD17899 awarded to Nathan A. Fox.

References

- Aiken LS, & West GM (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Hastings PD, Sanson AV, Ukoumunne OC, & Rubin KH (2010). Predicting mid-childhood internalising symptoms: A longitudinal community study. The International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 12, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Sanson AV, & Hemphill SA (2006). Parent influences on early childhood internalizing difficulties. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27, 542–559. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2006.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Hérot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, & Farone SV (2001). Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1673–1979. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, & Baugher M (1999). Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1230–1236. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Brown E, & Slater A (1996). Patterns of stability and continuity in attention across early infancy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA (2011). Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear, regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology, 47, 804–819. doi: 10.1037/a0023227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, & Plomin R (1984). Temperament: Early Developing Personality Traits. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA, & Marshall TR (1996). Behavioral and physiological antecedents of inhibited and uninhibited behavior. Child Development, 67, 523–540. doi: 10.2307/1131830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, & Silva PA (1996). Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 1033–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase RM, & Eyberg SM (2008). Clinical presentation and treatment outcome for children with comorbid externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan K, Pine D, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson H, Diaz Y, … Fox N (2009). Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Arbeau KA, & Armer M (2008). Don’t fret, be supportive! Maternal characteristics linking child shyness to psychosocial and school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 359–371. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9183-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, Almas AN, & Fox NA (2010). Temperament and the environment in the etiology of childhood anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry,51, 497–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02228.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan KA, & Fox NA (2007). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: Multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 729–746. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degnan K, Henderson H, Fox N, & Rubin K (2008). Predicting social wariness in middle childhood: The moderating roles of childcare history, maternal personality, and maternal behavior. Social Development, 17, 471–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00437.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson W, Klein DN, Olino TM, Dougherty LR, Durbin CE (2011). Social and non-social behavioral inhibition in preschool-age children: Differential associations with parent-reports of temperament and anxiety. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 42, 390–405. doi: 10.1007.1007/s10578-011-0225-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards SL, Rapee RM, & Kennedy S (2010). Prediction of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: Examination of maternal and paternal perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 313–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emde RN, Plomin R, Robinson J, Corley R, DeFries J, Fulker DW, … Zahn-Waxler C (1992). Temperament, emotion, and cognition at fourteen months: The MacArthur longitudinal twin study. Child Development, 63, 1437–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Klein MH, Slattery MJ, Goldsmith HH, & Kalin NH (2010). Early risk factors and development pathways to chronic high inhibition and social anxiety disorder in adolescence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 40–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.07010051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, & Boggs SR (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Shaw DS, & Moilanen KL (2011). Parental negative control moderates the shyness-emotion regulation pathway to school-age internalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 425–436. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9469-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox N, Henderson H, Marshall P, Nichols K, & Ghera M (2005). Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 56, 235–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox N, Henderson H, Rubin K, Calkins S, & Schmidt L (2001). Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development, 72, 1–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H, & Ladd GW (2003). Anxious solitude and peer exclusion: A diathesis-stress model of internalizing trajectories in childhood. Child Development, 74, 257–278. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle H (2008). Behavioral profiles of anxious solitary children and heterogeneity in peer relations. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1604–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson WA (1959). Three multivariate models: factor analysis, latent structure analysis and latent profile analysis. Psychometrika, 24, 229–252. doi: 10.1007/BF02289845 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH (1996). Studying temperament via construction of the Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire. Child Development, 67, 218–235. doi: 10.2307/1131697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hane AA, Cheah C, Rubin KH, & Fox NA (2008). The role of maternal behavior in the relation between shyness and social reticence in early childhood and social withdrawal in middle childhood. Social Development, 17, 795–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-07.2008.00481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Biederman J, Henin A, Faraone SV, Davis S, Harrington K, & Rosenbaum JF (2007). Behavioral inhibition in preschool children at risk is a specific predictor of middle childhood social anxiety: A five-year follow-up. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 28, 225–233. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000268559.34463.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Masek B, Henin A, Blakely LR, Pollock-Wurman RA, McQuade J, … Biederman J (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy for 4- to 7-year old children with anxiety disorders: A randomized control trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 498–510. doi: 10.1037/a0019055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, Bloomfield A, Biederman J, & Rosenbaum J (2008). Behavioral inhibition. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 357–367. doi: 10.1002/da.20490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, Dodd HF, & Bovopoulos N (2011). Treatment, family environment and anxiety in preschool children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 939–951. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9502-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, Dodd HF, Lyneham HJ, & Bovopoulous N (2011). Temperament and family environment in the development of anxiety disorder: Two-year follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 1255–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J (1997). Temperament and the reactions to the unfamiliarity. Child Development, 68, 139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, & Snidman N (1987). The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Development, 58, 1459–1473. doi: 10.2307/1130685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, … Ryan N (1997). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children–Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA & Rubin DB (1987) Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. J. Wiley & Sons, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Luebe AM, Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2011). Toddlers’ context-varying emotions, maternal responses to emotions, and internalizing behaviors. Emotion, 11, 697–703. doi: 10.1037/a0022994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, & Rubin DB (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767–778. doi: 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Wood JJ, & Weisz JR (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micco JA, Henin A, Mick E, Kim S, Hopkins CA, Biederman J, & Hirshfeld-Becker DR (2009). Anxiety and depressive disorders in offspring at high risk for anxiety: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 1158–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills RS, & Rubin KH (1990). Parental beliefs about problematic social behaviors in early childhood. Child Development, 61, 138–151. doi: 10.2307/1131054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills RSL, & Rubin KH (1993). Socialization factors in the development of social withdrawal In Rubin KH & Asendorpf J (Eds.), Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, van Brakel AML, Arntz A, & Schouten E (2011). Behavioral inhibition as a risk factor for the development of childhood anxiety disorders: A longitudinal study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20, 157–170. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9365-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2011). Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JNM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2010). Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion, 10, 349–357. doi: 10.1037/a0018486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Edgar K, McDermott JNM, Korelitz K, Degnan KA, Curby TW, Pine DS, & Fox NA (2010). Patterns of sustained attention in infancy shape the developmental trajectory of social behavior from toddlerhood through adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1723–1730. doi: 10.1037/a0021064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, & Ma Y (1998). The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 559, 56–64 doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, & Oberklaid F (2000). Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 461–468. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200004000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM (1997). Potential role of childrearing practices in the development of anxiety and depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 17, 47–67. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(96)00040-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Kennedy SJ, Ingram M, Edwards SL, & Sweeney L (2010). Altering the trajectory of anxiety in at-risk young children. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 1518–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeb-Sutherland BC, Vanderwert RE, Degnan KA, Marshall PJ, Pérez-Edgar K, Chronis-Tuscano A, … Fox NA (2009). Attention to novelty in behaviorally inhibited adolescents moderates risk for anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 1365–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02170.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, & Plomin R (1977). Temperament in early childhood. Journal of Personality Assessment, 41, 150–156. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4102_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH (2001). The Play Observation Scale (POS). Unpublished instrument. University of Maryland. Available from author. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess K, & Hastings P (2002). Stability and social-behavioral consequences of toddlers’ inhibited temperament and parenting behaviors. Child Development, 73, 483–495. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, & Cheah CSL (2000). The Parental Warmth and Control Scale. Unpublished instrument. University of Maryland. Available from author. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, & Bowker JC (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 141–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Hymel S, Mills RSL, & Rose-Krasnor L (1991). Conceptualizing different pathways to and from social isolation in childhood In Cicchetti D & Toth S (Eds.), The Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology, Vol. 2, Internalizing and Externalizing Expressions of Dysfunction, (pp. 91–122). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Nelson LJ, Hastings P, & Asendorpf J (1999). The transaction between parents’ perceptions of their children’s shyness and their parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 23, 937–958. doi: 10.1080/016502599383612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Snidman N, & Kagan J (1999). Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Adademy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1008–1015. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, & Albano AM (1996). The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children for DSM-IV, Child and Parent Versions. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Kurtines WM, Jaccard J, & Pina AA (2009). Directionality of change in youth anxiety treatment involving parents: An initial experiment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 474–485. doi: 10.1037/a0015761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Baruch DE, Duplinsky MS, & Lejuez CW (2008). Illicit drug use across the anxiety disorders: Prevalence, underlying mechanisms, and treatment In Zvolensky MJ & Smits JAJ (Eds.), Anxiety in health behaviors and physical illness (pp. 55–79). New York, NY: Springer Science and Business Media. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-74753-8_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Bruggen CO, Stams GJJM, & Bögels SM (2008). The relation between child and parent anxiety and parental control: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 1257–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Sigman M, Hwang W, & Chu BC (2003). Parenting and childhood anxiety: theory, empirical findings, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 134–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]