Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) use intensive care at the end of life and die in a hospital more frequently than patients with cancer or heart disease. Advance care planning (ACP) can help align treatment with patient preferences and improve patient-centered care, yet ACP quality and experiences among older patients with CKD and their care partners remain incompletely understood, particularly among the non–dialysis-dependent population.

Study Design

In-person interviewer-administered surveys of patients 70 years and older with non–dialysis-dependent CKD stage 4 or 5 and their self-identified care partners.

Setting & Participants

42 participants (31 patients, 11 care partners) at 2 clinical sites in greater Boston.

Outcomes

Completion of advance directives and self-reported perceptions, preferences, and experiences of ACP.

Analytical Approach

Descriptive analysis of patient and care partner surveys. McNemar test analysis to compare patient and care partner responses.

Results

Most patients had written advance directives (64%) and surrogate decision makers (81%). Although patients reported positive perceptions and high trust in their clinicians’ judgment, few (16%) had actually discussed preferences for life-sustaining treatment with their nephrologists. Few ACP discussions included components reflective of high-quality ACP: 16% of patients had been asked about their values concerning end-of-life care and 7% had discussed issues of decision-making capacity and consent to care should their health decline. When presented with 2 hypothetical scenarios (stroke/heart attack or dementia), nearly all patients and care partners reported a preference for comfort care over delaying death. Care partners were more likely than patients to report that they had experienced discussion components reflective of high-quality ACP with the clinical team.

Limitations

Single metropolitan area; most patients did not identify a care partner; nonresponse bias and small sample size.

Conclusions

Patients often believed that their clinicians understood their end-of-life wishes despite not having engaged in ACP conversations that would make those wishes known. Improving clinical ACP communication may result in end-of-life treatment that better aligns with patient goals.

Index Words: Decision-making, kidney disease, advance directives, caregiving, advance care planning, shared decision-making

Editorial, p. 102

Efforts to increase advance care planning (ACP) for patients with serious illness are growing, including reimbursement introduced by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in 2016. ACP is especially important for older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) because they face difficult decisions about dialysis initiation, often have poor prognoses, and frequently experience cognitive decline, limiting their ability to engage in treatment decision making.1, 2, 3 The 1-year mortality rate after dialysis initiation for adults older than 65 years is estimated at ∼30% using US Renal Data System data and at ∼54.5% using national representative survey data, with older non-Hispanic white patients and those with comorbid conditions faring worst.4,5 Compared with patients with similarly complex conditions such as cancer, patients with advanced CKD experience more than double the rate of death in the intensive care unit (32.3% vs 13.4%), often contradicting patient preferences to die at home.6

Although nearly a third of adults older than 60 years have CKD, their experiences with ACP have been understudied compared with patients with other high-mortality diseases.4,5 The experiences of older adults with advanced CKD (stages 4-5 CKD) who are not receiving dialysis are particularly understudied, and evidence suggests that this non–dialysis-dependent population faces unique barriers to high-quality end-of-life care, such as tension with their clinicians over the decision to forgo dialysis and aligning care with patient goals.7

There is increasing recognition that ACP may improve the quality of end-of-life care for patients with serious illnesses, particularly those with diminishing ability to engage in medical decisions.8,9 Especially for patients with advanced CKD who wish to forgo dialysis, ACP can preserve patient autonomy by ensuring that patient values, goals, and preferences for care are communicated to clinicians before the development of incapacity or the need for urgent decision making.8 A systematic review of ACP interventions across a wide range of settings and illnesses found that ACP reduced hospitalizations, increased use of hospice, and increased compliance with patients’ wishes.10 Among older adults with CKD and cardiovascular diseases, ACP improved shared decision making: a process in which patients, care partners, and clinicians discuss options for care in the context of patient values, preferences, and goals.11 ACP also increased patient and family satisfaction, reduced decisional conflict (uncertainty when making a choice), and improved family bereavement outcomes among elderly patients.12 Among the maintenance dialysis population, ACP also increased patient–care partner congruence in decision making.13,14 Experiences among the non–dialysis-dependent advanced CKD population remain incompletely understood. This study aims to address that gap.7

Despite the importance of ACP for older patients with advanced CKD, including those not receiving dialysis, and findings that most patients are eager to discuss their preferences, ACP rarely occurs until near death and often focuses on the less effective written advance directives rather than iterative discussion-based approaches.9,10,15, 16, 17, 18 However, timely discussions of prognosis between patients and clinicians are associated with less emotional distress, increased patient trust in clinicians, and enhanced patient hope.10,19,20 Focusing on older non–dialysis-dependent patients with advanced CKD, this study examines patient and care partner preferences, perceptions, and experiences related to ACP. Understanding patient-centered values and preferences for ACP may improve strategies to support patients, decision-making surrogates, and clinicians, as well as clarify opportunities for improvement, particularly in the period before the decision to initiate or forgo dialysis.

Methods

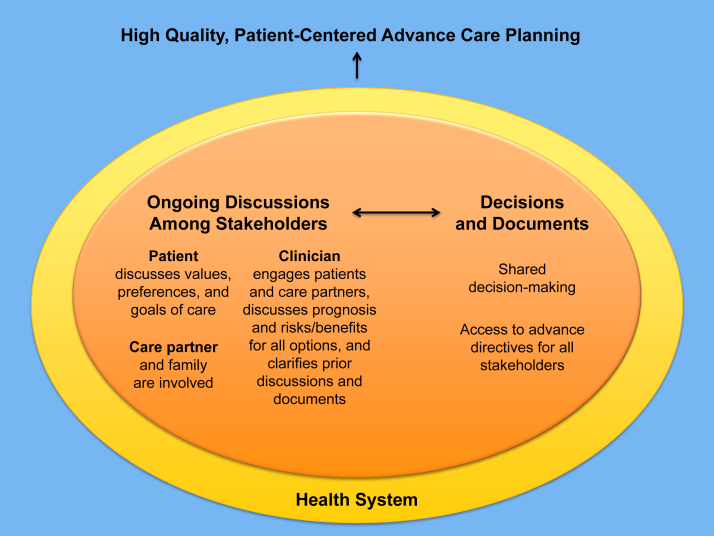

Core components of high-quality patient-centered ACP include prehospitalization discussion of patient preferences, prognostic discussion, documentation in the medical record, and organizational mechanisms to enable access to up-to-date written advance directives.21 Figure 1 outlines ACP quality indicators and illustrates how key stakeholders (patients, care partners, and clinicians) can achieve shared decision making and high-quality patient-centered ACP. Drawing on this framework, we conducted a survey of patients older than 70 years with CKD stages 4 to 5 (non–dialysis-dependent) and their care partners to assess preferences, perceptions, and experiences with ACP (survey questions included as Item S1). We also examined the degree to which care partners could accurately predict the end-of-life preferences of their loved ones by using 2 vignettes.14

Figure 1.

Interconnected components of high-quality patient-centered advance care planning (ACP) for patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. Informed by the Sinuff et al21 (2015) list of ACP quality indicators.

This study was approved by the Tufts Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (#12345).

Data Collection

At 2 outpatient nephrology clinics in the greater Boston area, electronic health records were used to screen for eligible patients. Eligibility criteria included: English speaking, 70 years or older, advanced CKD (stages 4 or 5, non–dialysis-dependent), and >15% risk for developing kidney failure according to the Kidney Failure Risk Equation with a time horizon of 5 years.22 Potentially eligible patients were either mailed information about the study or approached in person by study staff at clinic visits. Study coordinators met with eligible patients, explained the study, and consented interested patients.

Enrolled patients were asked to identify a care partner using a standardized validated social network question, asking them to name “someone with whom they discuss important matters” and who would be most likely to assist in decision making.23 These care partners were approached and consented following patient permission. Patients were interviewed in person following a routine nephrology or other clinical visit, while care partner interviews were completed by mail, telephone, or in person based on care partner preference. Trained interviewers read each question aloud to patients and recorded their responses, using visual aids as needed.

Measures

Patient characteristics included self-reported demographics, laboratory results from medical record review, and results from the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL-36) questionnaire, which assessed the effects and burdens of kidney disease on patients’ quality of life.24 Patients self-reported their ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living and activities of daily living to assess independence and functional disability.25 The rest of the survey included questions to assess patients’ understanding of advance directives, participation in ACP, and the Quality of Patient-Clinician Communication About End-of-Life Care scale.26 Developed for patients with AIDS, the 4-question instrument assessed communication between patients and clinicians by asking clinicians’ level of understanding and care for patients and patient preferences. Answers of “no,” “probably yes,” and “definitely yes” were scored as 1, 2, and 3, respectively, yielding a range from 4 to 12 when summing the 4 questions, with higher scores suggesting better interactions about the quality of end-of-life care communications.

Cultural sensitivity questions assessed how strongly patients believed that their clinicians understood their values and respected them.27 To assess patients’ and care partners’ ACP experiences with clinicians, questions were adapted from the conceptual model of Sinuff et al21 and ranking of ACP quality indicators, many of which correlate to the Renal Physicians Association’s clinical practice guidelines for shared decision making.21,28 Last, to assess their care goals, patients and care partners independently answered whether in 2 hypothetical scenarios: (1) a sudden stroke or heart attack and (2) development of dementia, they would prefer either life-sustaining treatment (including dialysis) that delays death or comfort care.14 Comfort care was described as “For example, speaking to you about palliative care or treating symptoms like pain without trying to cure or control your underlying illness.”

Statistical Analyses

We used SPSS (version 25; IBM Corp) to perform descriptive analyses on survey data, determining the frequency and proportion of responses among patients and care partners. McNemar χ2 test compared care partner responses with those of the patient partners.

Results

Sample Enrollment and Characteristics

Of 89 patients approached for participation (60 by mail and 29 in clinic), 51.7% of patients approached in clinic consented and 30% of patients consented following recruitment letters. All care partner participants were approached and surveyed in person when they accompanied their patient partners to clinic visits. In total, 42 participants (31 patients and 11 care partners) completed surveys. Mean patient age was 79±6.5 years, 67% were men, and 77% completed high school. Average estimated glomerular filtration rate was 20±4.9 mL/min/1.73 m2. All patients had difficulty with 1 or more instrumental activities of daily living, and 13% of patients had difficulty with 1 or more activities of daily living (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristics | All Patients (n = 31) | Patients Without Care Partners (n = 20) | Patients With Care Partners (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 79 ± 6.5 | 77 ± 6.2 | 79 ± 7.0 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 21 (68%) | 13 (65%) | 8 (73%) |

| Women | 10 (32%) | 7 (35%) | 3 (27%) |

| Race | |||

| White | 24 (77%) | 14 (70%) | 10 (91%) |

| Black or African American | 4 (13%) | 4 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| Asian | 1 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 1 (3.2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 2 (6.5%) | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Married or living with partner | 16 (52%) | 9 (45%) | 7 (64%) |

| Unmarried | 15 (48%) | 11 (55%) | 4 (36%) |

| Highest level of education | |||

| <High school | 7 (23%) | 4 (20%) | 3 (27%) |

| High school | 6 (19%) | 3 (15%) | 3 (27%) |

| Some college | 5 (16%) | 4 (20%) | 1 (9%) |

| College or postgraduate | 13 (42%) | 9 (45%) | 4 (36%) |

| Annual household income | |||

| <$25,000 | 5 (16%) | 3 (15%) | 2 (18%) |

| $25,000-$50,000 | 7 (23%) | 3 (15%) | 4 (36%) |

| >$50,000 | 15 (48%) | 10 (50%) | 5 (45%) |

| Not specified | 5 (16%) | 5 (25%) | 0 (0%) |

| Difficulty with ≥1 ADL | 4 (13%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (27%) |

| Difficulty with ≥1 IADL | 31 (100%) | 20 (100%) | 11 (100%) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 20 ± 4.9 | 21 ± 5.0 | 18 ± 4.0 |

| KDQOL-36: Effects of Kidney Disease score | 86 ± 15 | 88 ± 15 | 82 ± 13 |

| KDQOL-36: Burden of Kidney Disease score | 77 ± 25 | 80 ± 24 | 71 ± 27 |

Note. Numbers reflect the frequency with which each response was selected. Values expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number (percent), unless otherwise noted. The survey measures have been abbreviated for clarity.

Abbreviations: ADL, activity of daily living; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IADL, instrumental activity of daily living; KDQOL-36; Kidney Disease Quality of Life questionnaire.

Knowledge and Completion of Advance Directives

Nearly half (48%) the patients reported knowing what an advance directive was. After being provided a definition, 65% of patients stated that they had an advance directive. The most commonly cited reason for not having an advance directive among patients was not knowing what an advance directive was (18%) or having never thought about signing one (11%). Among those who had an advance directive, 68% had a durable power of attorney for health care and 32% had a living will. Access to advance directives was commonly limited to a patient’s family (57%), whereas 17% stated that their lawyer or clinician had access. Overall, 32% of patients stored their advance directive at home compared with 25% at the hospital and 21% with their family. Only 7% indicated that their advance directive was stored in their medical record.

Most (81%) patients had designated a surrogate decision maker in writing, and 58% of patients had discussed their preferences for life-sustaining treatments with their surrogate decision maker. However, only 16% of patients had discussed preferences for life-sustaining treatments with their nephrologist, and 19% had discussed their preferences for life-sustaining treatments with other health care clinicians (ie, a nurse, social worker, or spiritual care). Care partners were more likely than patients to say that they or the patient had discussed the patient’s advance directives, including preferences for life-sustaining treatments, with their clinicians (P = 0.04).

Patient Beliefs and Trust in Clinicians

Patients in general reported high levels of trust in their clinician’s judgments about their medical care (m=9.1±2.1, from 0-10) when assessing this clinician’s judgments about their medical care. Mean score for the Quality of Patient-Clinician Communication About End-of-Life Care scale was 10±1.6 (from 4-12). Most (68%) patients said that their clinician “definitely” cared about them, 68% believed that their clinician listened to them in these discussions, and 77% believed that their clinician gave them sufficient attention. In a set of questions examining cultural sensitivity, 61% said that they “strongly agreed” that their clinician understood their background and values and 87% “strongly disagreed” that their clinician lacked respect for them and the way they lived their lives (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality of Patient-Clinician Communication About End-of-Life Care and Cultural Sensitivity

| Survey Measure | Patient Attitudes (n = 31) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely Yes | Probably Yes | No | |

| Clinician knows treatment preferences | 12 (40%) | 16 (50%) | 3 (10%) |

| Clinician cares about patient | 21 (68%) | 10 (32%) | 0 (0%) |

| Clinician listens to what patient has to say | 21 (68%) | 10 (32%) | 0 (0%) |

| Clinician gives patient enough of his or her attention | 24 (77%) | 6 (19%) | 1 (3%) |

| Poor | Fair | Good | Very Good | Excellent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall quality of ACP conversations | 4 (15%) | 6 (22%) | 5 (19%) | 6 (22%) | 6 (22%) |

| Strongly Agree | Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural sensitivity | ||||

| Clinician understands my values | 19 (61%) | 8 (26%) | 2 (6.5%) | 2 (6.5%) |

| Clinician looks down on me | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (10%) | 27 (87%) |

Note. Numbers reflect the frequency with which each response was selected. Values expressed as number (percent). The survey measures have been abbreviated for clarity.

Abbreviation: ACP, advance care planning.

Quality and Experience With ACP Discussions

Despite high levels of trust, more than a third (37%) of patients rated conversations with nephrologists about their end-of-life treatment preferences “poor” or “fair.” Moreover, only 40% of patients thought their nephrologist “definitely” knew the kinds of treatment they would want if they became too sick to speak for themselves (Table 3). Few (26%) patients in our survey had engaged in discussions about prognosis. Just 16% of patients reported discussing the outcomes, benefits, and burdens (or risks) of life-sustaining medical treatments with their clinicians. Still fewer (10%) patients had been involved in discussions about preferences for conservative care. A quarter (23%) of patients received help from their health care team accessing legal documents to communicate their advance care plans, and just 7% of patients and their families recalled being offered the opportunity to discuss issues around capacity to engage in decision making and consent to care. Only 16% of patients recalled having been asked by a clinician about what was important to them, such as values, spiritual beliefs, or other practices as they consider health care decisions, and about half (45%) of patients indicated that they were given the opportunity to express their fears or concerns. A minority (39%) of patients indicated that they were given the opportunity for clarification questions, and 42% of patients indicated that they had been informed that they could change their mind regarding goals of care decision making (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient Experiences of Advance Care Planning Discussions with Clinicians

| Has a member of the clinical team talked to you about… | All Patients (n = 31) |

Patients Without Care Partners (n = 20) |

Patients With Care Partners (n = 11) |

Care Partners (n = 11) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Prognosis | 8 (26%) | 22 (71%) | 5 (25%) | 14 (70%) | 3 (27%) | 8 (73%) | 1 (9%) | 9 (82%) |

| Outcomes of life-sustaining medical treatments | 5 (16%) | 26 (84%) | 4 (20%) | 16 (80%) | 1 (9%) | 10 (91%) | 3 (27%) | 7 (64%) |

| Outcomes of conservative care | 3 (10%) | 28 (90%) | 2 (10%) | 18 (90%) | 1 (9%) | 10 (91%) | 4 (36%) | 6 (55%) |

| You and your family meeting with the clinician to discuss treatment options | 6 (19%) | 24 (77%) | 4 (20%) | 15 (75%) | 2 (18%) | 9 (82%) | 6 (55%) | 4 (36%) |

| Prior discussions or documents regarding life-sustaining treatments | 5 (16%) | 24 (77%) | 4 (20%) | 14 (70%) | 1 (9%) | 10 (91%) | 7 (64%) | 2 (18%) |

| What is important to you/your loved ones regarding health care decisions at this stage of your life | 5 (16%) | 25 (81%) | 4 (20%) | 15 (70%) | 1 (9%) | 10 (91%) | 4 (36%) | 5 (46%) |

| Your fears or concerns | 14 (45%) | 16 (52%) | 11 (55%) | 8 (40%) | 3 (27%) | 8 (73%) | 6 (55%) | 2 (18%) |

| Any questions or clarifications regarding your overall goals of care | 12 (39%) | 17 (55%) | 7 (35%) | 11 (55%) | 5 (45%) | 6 (55%) | 5 (46%) | 4 (36%) |

| Treatments you prefer to have or not have if you develop a life-threatening illness | 6 (19%) | 24 (77%) | 5 (25%) | 14 (70%) | 1 (9%) | 10 (91%) | 3 (27%) | 4 (36%) |

| The option to change your mind regarding decisions around the goals of care | 13 (42%) | 16 (52%) | 10 (50%) | 8 (40%) | 3 (27%) | 8 (73%) | 4 (40%) | 3 (30%) |

| An opportunity to discuss capacity and consent with regard to advance care planning | 2 (7%) | 26 (84%) | 2 (10%) | 15 (75%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (100%) | 3 (27%) | 5 (46%) |

| Support from the allied health care team as needed? | 2 (75%) | 29 (93%) | 2 (10%) | 18 (90%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (100%) | 6 (55%) | 5 (46%) |

| ”Goals of care discussion” information to look at before conversations with the clinician? | 3 (10%) | 26 (84%) | 3 (15%) | 15 (75%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (100%) | 4 (36%) | 5 (46%) |

| Accessing legal documents to communicate you/your loved one’s Advance Care Plans? | 7 (23%) | 24 (77%) | 5 (25%) | 15 (75%) | 2 (18%) | 9 (82%) | 3 (27%) | 8 (73%) |

Note. Numbers reflect the frequency with which each response was selected. Values given as number (percent). The survey measures have been abbreviated for clarity.

Most questions about patient experiences with clinicians were answered similarly among patients and their care partners, but care partners were more likely to say that a clinician had offered to arrange a family meeting (P = 0.04) and more likely to say that they had been asked by a clinician about prior discussions or written documents about the use of life-sustaining treatment (P = 0.01). Care partners were also more likely to say that their loved one had been offered support from the allied health care team (P = 0.03).

Goals of Care Concordance Among Patients and Care Partners

Two hypothetical scenarios (stroke/heart attack or development of dementia) were presented to patients and care partners, using a measure developed and used in other studies with older patients with CKD.14 In each scenario, 84% and 81% of patients, respectively, preferred a focus on comfort care over life-prolonging treatment. None of the care partners preferred for the patient to delay death in either scenario, although many (44% and 22%, respectively) reported uncertainty. In comparing care partner and patient responses, there was usually agreement on focusing on comfort as the preferred approach, with the exception of 2 patients preferring life-prolonging treatment in the first scenario while their care partners preferred otherwise or were unsure (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patient and Care Partner Concordance on Goals of Care

| All Patients (n = 31) | Patients Without Care Partners (n = 20) | Patients With Care Partners (n = 11) | Care Partners (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke or heart attack | ||||

| Goals of care should be focused on delaying death | 2 (6%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Goals of care should be focused on comfort and peace | 26 (84%) | 18 (90%) | 8 (73%) | 5 (56%) |

| I am not sure | 3 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (18%) | 4 (44%) |

| Dementia | ||||

| Goals of care should be focused on delaying death | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Goals of care should be focused on comfort and peace | 25 (81%) | 17 (85%) | 8 (73%) | 7 (78%) |

| I am not sure | 5 (16%) | 3 (15%) | 2 (18%) | 2 (22%) |

Discussion

Our findings align with prior literature in demonstrating the need for ACP among patients with CKD, especially before they reach the decision to initiate dialysis given that the non–dialysis-dependent population faces unique barriers to patient-centered ACP.2,3,7,9 In our study of older adults with advanced non–dialysis-dependent CKD, most believed that clinicians knew their preferences for treatment if their condition were to progress, though few had actually discussed this with their clinicians. Patients reported high levels of trust and communication quality with clinicians, consistent with findings for patients with other complex chronic diseases.26 Despite this, most patients reported ACP communication experiences that did not satisfy ACP quality indicators.10,19, 20, 21 Most had not discussed possibilities of changing their mind or losing the ability to consent to care and few had discussed values or been offered help to complete written advance directives. This highlights an opportunity for improvement: high levels of trust among patients with advanced CKD in their clinicians should be buttressed by increased communication about ACP.29 These conversations are especially important to protect the autonomy of patients who opt to forgo dialysis.

Nephrology clinicians are critical to ACP because they can facilitate a discussion of prognosis and disease trajectory with patients and families. Though challenging, these conversations may improve end-of-life outcomes and reduce emotional distress.19 However, few patients had discussed prognosis with their clinicians despite evidence that patients want to know their prognosis even when their predicted outcomes are not desirable.18 Reluctance to discuss prognosis with patients with advanced CKD may be partly due to limited CKD-specific validated tools estimating life expectancy needed to assist clinicians in providing effective and compassionate guidance.30,31 Studies demonstrate that for patients with serious illness such as advanced cancer, discussion of prognosis is associated with more realistic patient expectations and has not been shown to harm patients’ emotional well-being or patient-physician relationships.32 Lack of training in having ACP conversations, time constraints, and loss of revenue from foregoing dialysis may also deter clinicians from engaging patients in ACP.33

Involving family in ACP discussions is also critical to shared decision making because they may know and understand the patients’ values, goals, and preferences. Our results demonstrate that some patients who have not engaged in ACP discussions with their clinicians may already be discussing ACP with loved ones, highlighting a missed opportunity for clinicians to engage both patients and care partners in decision making. Among our participants, more patients had formally designated a surrogate decision maker than had completed a written advance directive. Most patients had discussed the use of life-sustaining treatment with their surrogate decision maker (often a family member), whereas few patients discussed this with clinicians. However, ACP has been demonstrated to be most effective when clinicians introduce the topic and promote shared decision making with the patient and his or her family, leading to greater patient and family satisfaction and congruence and reduced decisional conflict.11,12,14

Our findings also demonstrate that patients and their care partners do not always remember discussions with clinicians similarly. In a systematic review of the effect of ACP on surrogate decision makers for patients with chronic illnesses, at least one-third experienced negative emotional burdens, including stress, guilt, and doubt, which were often substantial and long lasting.34,35 Facilitating ACP communication between the patient-family-clinician triad to ensure that surrogate decision makers know which treatment is consistent with patients’ preferences can reduce the emotional burden on surrogate decision makers.31,34 This reinforces the need for iterative discussions over time and for starting ACP conversations earlier, before decision making is needed. Clinicians should attempt to engage patients and their families together because improved shared decision-making efforts could increase patients’ understanding of their disease and care options, as well as improve concordance and help all members of the patient-family-clinician triad have a mutual understanding of the patients’ preferences and treatment path.

Last, when presented with specific scenarios in which longer life would be associated with substantial negative impacts on quality of life, this study showed that nearly all patients and care partners expressed a preference for focusing on comfort over delaying death as a care goal. This is consistent with previous research demonstrating that patients who experience appropriate ACP are more likely to receive conservative care in alignment with their wishes and less likely to die in a hospital.36 Thus, the integration of ACP into usual care for older patients with advanced CKD and their care partners presents an important opportunity to delineate patients’ goals, values, and preferences to best tailor and align their future care. Among patients already receiving dialysis, ACP is associated with an increased propensity for dialysis withdrawal, a finding that likely demonstrates how ACP can increase patient knowledge of alternatives to dialysis and improve congruence of care with patient wishes because many of these patients may prefer conservative care over dialysis.13 Given that many patients with advanced CKD start or prepare to start dialysis despite significant comorbid conditions or advanced age, improving ACP could potentially prevent unwanted high-intensity treatment or a pathway for withdrawal for advanced-stage patients for whom conservative care may better align with their goals and preferences.37,38

Study strengths include a wide and comprehensive range of questions that assessed both perceptions and experiences regarding ACP, and that patient and care partner responses were directly compared. In addition, the method of individual 1-on-1 surveys allowed for clarifications to be made when necessary and for the patients to go at their own pace, reducing response bias and increasing patient comfort.

Our study is not without limitations, including enrolling moderate- to high-functioning older adults without severe cognitive issues and with overall high education levels, a small sample size, and 35% response rate. In addition, all participants lived in the greater Boston area and many were white men, limiting generalizability. For the survey question of patient trust in their clinicians, the high reported level of trust had a strong ceiling effect, limiting its accuracy. Questions regarding patient attitudes were measured on a scale that was loaded toward a positive answer, and the ACP conservation quality rating question did not include a not applicable response for participants who may not have had any ACP conversations. The simplicity of the hypothetical goals of care scenarios may not be directly applicable to real life. Additionally, the statistical comparisons between patient and care partner responses should be interpreted with caution owing to the small sample size of care partners.

Currently, our team is leading the Decision-Aid for Renal Therapy (DART) trial (clinicaltrials.gov NCT03522740), a larger multisite study examining the comparative effectiveness of an interactive web-based decision aid to help older patients with advanced CKD and their care partners choose treatment aligned with their preferences and complete ACP. The DART study aims also to extend the findings of this study to the wider and more diverse population of older adults with advanced CKD.

Though patients perceive that their clinicians understand their treatment wishes, this perception often does not align with the completion of key ACP steps during end-of-life care discussions. Clinicians should communicate prognosis and include both patients and families in ACP discussions, especially because these conversations often already occur in the patient-family context and this dyad may have some differences in their perceptions of clinical interactions. With the July 2019 announcement of the Advancing American Kidney Health Initiative,39 upcoming models likely will include greater incentives and improved reimbursement for patient and care partner education and for conservative and palliative care options. By focusing on key ACP steps, clinicians may be able to improve concordance between patient preferences and treatment received and congruence between patients and care partners, as well as increase the numbers of patients who have written advance directives, ultimately resulting in more patient-centered care.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Tira Oskoui, BS, Renuka Pandya, PhD, Daniel E. Weiner, MD, MS, John B. Wong, MD, Susan Koch-Weser, ScM, ScD, and Keren Ladin, PhD, MSc.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: KL, JBW, DEW, SK-W; data acquisition: KL, TO, RP; data analysis: TO. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy and integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), award number KL2TR002545 (Dr Ladin). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The funder had no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Satia A. Marotta, PhD, for help with data analysis.

Peer Review

Received July 9, 2019. Evaluated by 3 external peer reviewers and a statistician, with editorial input from an Acting Editor-in-Chief (Editorial Board Member Jennifer S. Scherer, MD). Accepted in revised form November 11, 2019. The involvement of an Acting Editor-in-Chief to handle the peer-review and decision-making processes was to comply with Kidney Medicine’s procedures for potential conflicts of interest for editors, described in the Information for Authors & Journal Policies.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Item S1: Survey questions.

Supplementary Material

Item S1.

References

- 1.Berger I., Wu S., Masson P. Cognition in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0745-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison S.N., Torgunrud C. The creation of an advance care planning process for patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49(1):27–36. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurella M., Chertow G.M., Fried L.F. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment in the elderly: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7):2127–2133. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wachterman M.W., O'Hare A.M., Rahman O.K. One-year mortality after dialysis initiation among older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(7):987–990. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saran R., Robinson B., Abbott K.C. US Renal Data System 2018 Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73:A7–A8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong S.P., Kreuter W., O’Hare A.M. Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(8):661–663. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong S.P., McFarland L.V., Liu C.-F., Laundry R.J., Hebert P.L., O’Hare A.M. Care practices for patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):305–313. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudore R.L., Lum H.D., You J.J. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331. e821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladin K., Buttafarro K., Hahn E., Koch-Weser S., Weiner D.E. “End-of-life care? I’m not going to worry about that yet.” Health literacy gaps and end-of-life planning among elderly dialysis patients. Gerontologist. 2017;58(2):290–299. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A., Rietjens J.A., van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014;28(8):1000–1025. doi: 10.1177/0269216314526272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briggs L.A., Kirchhoff K.T., Hammes B.J., Song M.-K., Colvin E.R. Patient-centered advance care planning in special patient populations: a pilot study. J Prof Nurs. 2004;20(1):47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Detering K.M., Hancock A.D., Reade M.C., Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirchhoff K.T., Hammes B.J., Kehl K.A., Briggs L.A., Brown R.L. Effect of a disease-specific advance care planning intervention on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):946–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song M.-K., Ward S.E., Fine J.P. Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: a randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):813–822. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hines S.C., Glover J.J., Holley J.L., Babrow A.S., Badzek L.A., Moss A.H. Dialysis patients' preferences for family-based advance care planning. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):825–828. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-10-199905180-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holley J.L., Stackiewicz L., Dacko C., Rault R. Factors influencing dialysis patients' completion of advance directives. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30(3):356–360. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luckett T., Sellars M., Tieman J. Advance care planning for adults with CKD: a systematic integrative review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):761–770. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladin K., Lin N., Hahn E., Zhang G., Koch-Weser S., Weiner D.E. Engagement in decision-making and patient satisfaction: a qualitative study of older patients' perceptions of dialysis initiation and modality decisions. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;32(8):1394–1401. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davison S.N., Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2006;333(7574):886. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38965.626250.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMahan R.D., Knight S.J., Fried T.R., Sudore R.L. Advance care planning beyond advance directives: perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinuff T., Dodek P., You J.J. Improving end-of-life communication and decision making: the development of a conceptual framework and quality indicators. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(6):1070–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tangri N., Grams M.E., Levey A.S. Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):164–174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burt R.S. Network items and the general social survey. Social Networks. 1984;6(4):293–339. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hays R.D., Kallich J.D., Mapes D.L., Coons S.J., Carter W.B. Development of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL TM) instrument. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(5):329–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00451725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spector W.D., Fleishman J.A. Combining activities of daily living with instrumental activities of daily living to measure functional disability. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(1):S46–S57. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.1.s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curtisa J.R., Patrick D.L., Caldwell E., Greenlee H., Collier A.C. The quality of patient-doctor communication about end-of-life care: a study of patients with advanced AIDS and their primary care clinicians. AIDS. 1999;13(9):1123–1131. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199906180-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saha S., Arbelaez J.J., Cooper L.A. Patient–physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1713–1719. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renal Physicians Association Working Group; Rockville, MD: 2010. Shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis: Clinical practice guidelines. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.renalmd.org/resource/resmgr/Store/Shared_Decision_Making_Recom.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sellars M., Clayton J.M., Morton R.L. An interview study of patient and caregiver perspectives on advance care planning in ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(2):216–224. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Couchoud C., Hemmelgarn B., Kotanko P., Germain M.J., Moranne O., Davison S.N. Supportive care: time to change our prognostic tools and their use in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(10):1892–1901. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12631115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holley J.L. Advance care planning in CKD/ESRD: an evolving process. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(6):1033–1038. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00580112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enzinger A.C., Zhang B., Schrag D., Prigerson H.G. Outcomes of prognostic disclosure: associations with prognostic understanding, distress, and relationship with physician among patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3809–3816. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.9239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladin K., Pandya R., Kannam A. Discussing conservative management with older patients with CKD: an interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(5):627–635. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wendler D., Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(5):336–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carson R.C., Bernacki R. Is the end in sight for the “don’t ask, don’t tell” approach to advance care planning? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(3):380–381. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00980117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silveira M.J., Kim S.Y., Langa K.M. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13):1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong S.P., Hebert P.L., Laundry R.J. Decisions about renal replacement therapy in patients with advanced kidney disease in the US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2000–2011. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(10):1825–1833. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03760416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Combs S.A. Working toward more effective advance care planning in patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(12):2107–2109. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10511016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Executive Order on Advancing American Kidney Health. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-advancing-american-kidney-health/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Item S1.