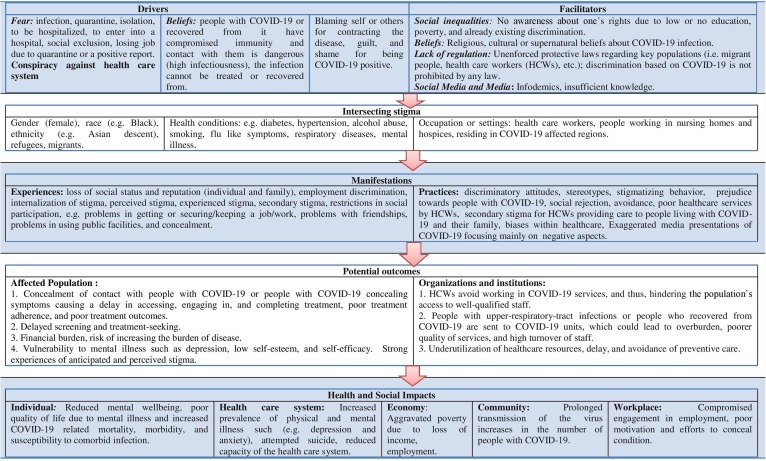

Being part of a social minority (e.g. migrants, people of color or Asian descent in Western countries) is not itself a risk factor for contracting Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). However, certain groups of people across the world are being targeted by COVID-19 related stigma (COS) and discrimination, which constitutes a growing concern (Bagcchi, 2020). There is an urgent need to better understand it, as it may pose a barrier for accessing testing and health care and for maintaining treatment adherence (Stangl et al., 2019). It is very likely that COS is the consequence of multiple socio-ecological drivers (e.g., fear, misinformation) and facilitators (e.g., racism, poverty) (Logie, 2020). In this letter, we attempt to explore COS related factors based on the real-life experiences of a group of psychiatrists from thirteen countries using the health stigma and discrimination framework (HSDF) (Stangl et al., 2019). We categorized these experiences as per the process domains (such as drivers, facilitators); and these process domains along with examples/responses are depicted in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Analysis of the stigmatization process for COVID-19 using Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework (HSDF).

In the majority of represented countries, COS was associated with similar drivers, (e.g., fear associated with the infection or the quarantine), beliefs (supra-natural or religious), and blame to self or others for contracting the disease, as well as guilt and shame. Common facilitators of COS were not being aware of one’s rights not to be discriminated against due to lack of education or lack of legislation or policies addressing discrimination, or lack of enforcement. Infodemic (i.e. excessive circulation of misinformation) acted both as a driver and facilitating factor for COS (Ransing et al., 2020). Unfortunately, most contributors in our group reported that these drivers and facilitators were inadequately addressed in their countries. In certain cases, the reinforcement of negative stereotypes and prejudice, plus social processes of labeling, further fueled already existing social inequalities, which were then reinforced by some public health enforcement measures (e.g., arresting people for breaching quarantine) (Clissold et al., 2020, Logie and Turan, 2020).

Most of the authors reported that people with current or past COVID-19 and their relatives, social minorities (depending on the country, it could include people from Asian descent or black races, and immigrants) and healthcare workers (HCWs) deployed in COVID-19 services have experienced and continue to experience COS. This has led to some HCWs and affected populations to suffer a range of stigma experiences and practices. These people have experienced, and are experiencing, discrimination such as the refusal of housing, verbal abuse or gossip, and social devaluation. Also, their family members or friends are experiencing ‘secondary’ or ‘associative’ stigma. Likewise, older people, people with premorbid illnesses, and marginalized people are suffering stigmatizing experiences and may not favor treatment due to scarcity of medical resources.

Furthermore, COS may have led to diminished access to health care and uptake of testing, delayed treatment and poor adherence to treatment, decreased acceptability of HCWs in their communities, and overall decreased resilience (i.e. power to challenge stigma). These outcomes may jeopardize their health and wellbeing. They are key outcomes for organizations and institutions, including laws and policies, the availability and quality of health services, law enforcement practices, and social protections. These manifestations are affecting the COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 organizations or institutions in different ways, as mentioned in Fig. 1 (Batty et al., 2020, Lassale et al., 2020).

Moreover, COS may increase already existing social inequalities by leading to further unemployment and poverty, and impede several social processes such as social integration. For example, documented and undocumented immigrants, refugees, ethnic and religious minorities, people recovered from COVID-19, and marginalized populations may experience socio‐economic exclusion due to rapid policy changes such as VISA restriction in some countries. Also, people who have experienced criminalization (due to breaching public health measures) may find reduced access to employment, housing, and healthcare, and may be exposed to exacerbated risks for suicide and violence in the pandemic and post-pandemic period (Shoib et al., 2020).

Previous infectious disease outbreaks [e.g. influenza A (H1N1), bubonic plague, Asiatic flu, cholera, Ebola virus disease, Zika virus, HIV, tuberculosis, SARS and MERS] have been associated with stigma and discrimination against some populations (Fischer et al., 2019). We noticed that most of our countries experiences related to COS were unfortunately somewhat expected based on the experience of similar stigmatizing processes during past infections outbreaks. However, due to the current extent of social media and mass media and immediate global communication via the internet, infodemic may boost COS continuously reinforcing it in ‘social media bubbles’ an ‘echo chambers’, and hindering any attempt to address it. At the same time, a lack of global policy or collaboration to address COS might further interfere with any efforts to address COS effectively and efficiently. Still, if unaddressed, COS may have severe catastrophic consequences on population health outcomes and community wellbeing.

To contribute to reducing COS and its negative impact, we collated recommendations for developing interventions using the HSDF (Table 1 ) (Stangl et al., 2019). We suggest that any adopted interventions should address drivers and facilitators, without disregarding underlying social and health inequities. They should be multi-component, multi-level (Logie and Turan, 2020), and directed towards broader social, cultural, political, and economic factors. More importantly, they should focus on empowering and strengthening communities. Also, these efforts require long term investments in transforming values, laws, rights, and policies (Logie, 2020). There is a pressing need to collect more systematic data to identify the complex factors related to COS and to improve our understanding of the way it intersects with social and health disparities, to identify gaps where new interventions or programs are required, and to develop appropriate strategies or improve existing programs addressing this problem (Table 1).

Table 1.

Brief Recommendations for developing interventions using the HSDF framework.

| Stages of Stigmatization process | Specific recommendations | General recommendations | Future directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drivers and facilitators |

|

|

|

| Intersecting stigma |

|

|

|

| Manifestations |

|

|

|

| Potential outcomes |

|

|

|

| Health and Social Impacts |

|

Abbreviations: CES: community-engaged strategies; COS: COVID-19 related stigma; HCWs: healthcare workers.

Our countries experiences suggest that COS is a global phenomenon. To address it, we need to amplify our collective ability to respond effectively through global collaborations in cross-disciplinary research and policy efforts. These experiences, put together through HSDF, provide an opportunity to explore the COS, to suggest efficient and effective interventions with the perspectives of clinicians, policymakers, researchers, and project implementers rather than focusing on individual’s experiences These developed interventions may appropriately address the complex realities of affected and vulnerable populations. We suggest that COS researchers should standardize the measures, compare outcomes, and build more effective cross-cutting interventions (Ransing et al., 2020b).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Early Career Psychiatrists Section of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) for being a supportive network that allowed to connect early career psychiatrists from different countries to work together on this initiative.

Funding

The authors declare that there was no funding for this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.033.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:782. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty G.D., Deary I.J., Luciano M., Altschul D.M., Kivimäki M., Gale C.R. Psychosocial factors and hospitalisations for COVID-19: prospective cohort study based on a community sample. Brain, Behavior, Immunity. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clissold E., Nylander D., Watson C., Ventriglio A. Pandemics and prejudice. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020937873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer L.S., Mansergh G., Lynch J., Santibanez S. Addressing disease-related stigma during infectious disease outbreaks. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2019;13:989–994. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2018.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassale C., Gaye B., Hamer M., Gale C.R., Batty G.D. Ethnic disparities in hospitalisation for COVID-19 in England: the role of socioeconomic factors, mental health, and inflammatory and pro-inflammatory factors in a community-based cohort study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie C.H. Lessons learned from HIV can inform our approach to COVID-19 stigma. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2020;23 doi: 10.1002/jia2.25504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie C.H., Turan J.M. How do we balance tensions between COVID-19 public health responses and stigma mitigation? Learning from HIV research. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2003–2006. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02856-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransing R., Adiukwu F., Pereira-Sanchez V., Ramalho R., Orsolini L., Schuh Teixeira A.L., Gonzalez-Diaz J.M., Pinto da Costa M., Soler-Vidal J., Bytyçi D.G., El Hayek S., Larnaout A., Shalbafan M., Syarif Z., Nofal M., Kundadak G.K. Mental health interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a conceptual framework by early career psychiatrists. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;102085 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransing R., Nagendrappa S., Patil A., Shoib S., Sarkar D. Potential role of artificial intelligence to address the COVID-19 outbreak-related mental health issues in India. Psychiatry Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransing R., Ramalho R., Orsolini L., Adiukwu F., Gonzalez-Diaz J.M., Larnaout A., Pinto da Costa M., Grandinetti P., Bytyçi D.G., Shalbafan M., Patil I., Nofal M., Pereira-Sanchez V., Kilic O. Can COVID-19 related mental health issues be measured? Brain Behav. Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoib S., Nagendrappa S., Grigo O., Rehman S., Ransing R. Factors associated with COVID-19 outbreak-related suicides in India. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.L. Stangl, V.A. Earnshaw, C.H. Logie, W. van Brakel, C.L. Simbayi, I. Barré, J.F. Dovidio, The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas, BMC Med. 17 (2019) 31, doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.