Requests for ophthalmologic evaluation for ocular symptoms are customary in medicine. Whether they are outpatient referrals (from optometrists,1 ophthalmologists,1 or other physicians1, 2, 3), inpatient consultations,4 or emergency referrals,1 , 4 it is convention for the requesting health care professional to specify a suspected diagnosis or to ask a clinical question in the request. However, the literature indicates limited reports examining the diagnostic accuracy of referring healthcare providers.1, 2, 3, 4 Currently, a growing need exists for ophthalmologists to accurately diagnose urgent and emergent ocular referrals remotely, which has been highlighted by the 2019 coronavirus pandemic.

The Wills Eye Hospital Emergency Department (ED) is a high-volume tertiary academic referral center that receives urgent and emergent referrals from outpatient offices, urgent care centers, and outside emergency departments. Referring health care professionals call triaging ophthalmology medical staff via a dedicated transfer line to establish appropriateness of the referral before patient transfer. This study was designed to prospectively evaluate the accuracy of referring health care professionals’ working diagnoses and to evaluate the ability of a telephone-triaging ophthalmologist to diagnose these urgent and emergent ocular conditions remotely.

After receiving approval from the Wills Eye Hospital Institutional Review Board, data were collected prospectively from all health care professionals and their patients who were referred to the Wills Eye Hospital ED via the dedicated transfer phone over a 3-month period (June 1, 2018–September 1, 2018). Referral data were collected by a triaging ophthalmology staff member (a second-year ophthalmology resident, supervised by an attending ophthalmologist) on free-text triage sheets and included history of present illness, referring provider specialty, and the working diagnosis. Before patient arrival, the triaging ophthalmologist recorded his or her own suspected diagnosis, based on the collected information, indicating if he or she agreed with the referring diagnosis. The triaging sheets were reviewed after the visit by an ophthalmology resident (J.D.D., D.C.A., D.J.O., L.B., or A.R.M.). Reviewers were masked appropriately to the referring, triaging, and final diagnoses as necessary. Coded diagnosis categories were generated from the free-text entries (Table S1, available at www.aaojournal.org).

After the patients’ visits, their charts were reviewed by a reviewer (J.D.D., D.C.A., D.J.O., L.B., or A.R.M.) to collect the final diagnosis and the anatomic location of the diagnosis. Again, reviewers were masked to the referring and triaging diagnoses. The final diagnosis was categorized by primary anatomic location: orbit and ocular adnexa, ocular surface and cornea, anterior segment, glaucoma, retina and vitreous, optic nerve, or central and peripheral nervous system. A final diagnosis was labeled a “can’t-miss diagnosis” if it could cause irreversible vision loss or death if not diagnosed and treated emergently. Can’t miss diagnoses included giant cell arteritis, cerebrovascular accident, ruptured globe, orbital compartment syndrome, acute angle-closure glaucoma, central nervous system lesion, third-nerve palsy, acute Horner’s syndrome, and endophthalmitis (Table S2, available at www.aaojournal.org). The final diagnosis was compared with the prospectively collected data to assess the accuracy of the referring and triaging diagnoses.

Over the study period, 530 patients were referred to the eye ED via the transfer line. Of these patients, 334 (63.0%) were included. The remaining patients were excluded for never appearing at the ED (n = 146 [27.5%]) or incomplete data (n = 50 [9.4%]). Most referring professionals were emergency medicine physicians (52.4% [n = 175]), followed by ophthalmologists (24.9% [n = 83]), optometrists (7.8% [n = 26]), and urgent care physicians (6.3% [n = 21]). Ten referring providers’ specialties (3.0%) were not recorded and were categorized as unknown.

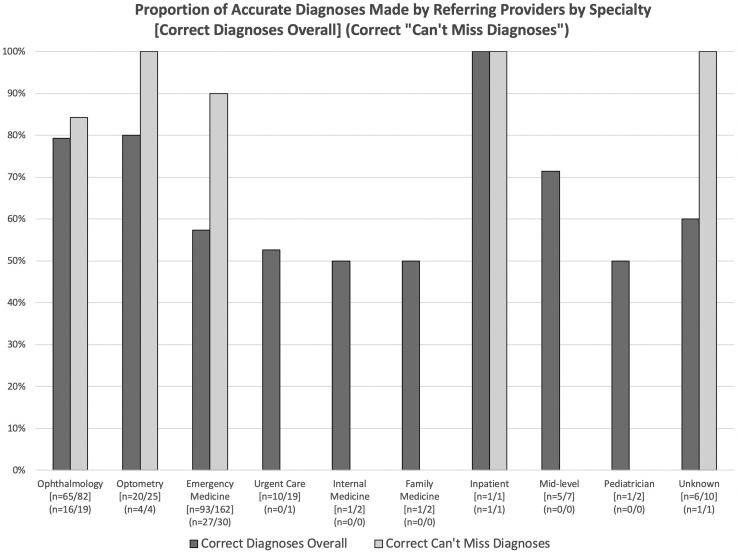

Overall, the referring professionals who provided a working diagnosis were correct in 65.1% of cases (n = 203/312). Eye specialists (ophthalmologists, optometrists, and unknown) made the correct referring diagnosis in significantly more cases (77.8% [91/117]) than non-eye specialists (57.4% [112/195]; X2 1 = 13.31; P < 0.001). A detailed breakdown of the diagnostic accuracy of referring professionals by specialty can be seen in Figure 1 (X2 9 = 16.58; P = 0.05). Non-eye specialists (n = 196) were most accurate at making diagnoses of the orbit and ocular adnexa (81.6% [31/38]), followed by ocular surface and cornea (63.0% [46/73]), glaucoma (61.5% [8/13]), anterior segment (42.9% [12/28]), retina and vitreous (38.2% [13/34]), central and peripheral nervous system (25.0% [2/8]), and optic nerve (0.0% [0/1]; X2 6 = 22.433, P = 0.001; Fig S2, available at www.aaojournal.org).

Figure 1.

Bar graph showing the proportion of accurate diagnoses made by referring providers by specialty. Data in brackets are correct diagnoses overall and data in parentheses are correct can’t-miss diagnoses.

Over the phone, the triaging ophthalmologists were able to interpret the reported histories, physical examination findings, and limited testing capabilities of the referring provider and to make the correct diagnosis in 69.9% of cases (n = 179/256). Prior studies have evaluated the reliability of tele-ophthalmology in the evaluation of diabetic retinopathy, clinically significant macular edema, ocular hypertension, and glaucoma, using a variety of tele-based services ranging from 41.3% to 90.0% accuracy.5 This study provides data on the ability of a telephone-triaging ophthalmologist to identify urgent and emergent ocular disorders referred by other medical professionals.

Both the referring professionals and the triaging eye ED staff more accurately identified can’t-miss diagnoses. Referring professionals correctly identified can’t-miss diagnoses in 87.5% of referrals (n = 49/56) compared with all other conditions 60.1% (154/256; X2 1 = 15.11; P < 0.001). Similarly, the triaging ophthalmology staff correctly identified can’t-miss diagnoses in 97.2% of referrals (n = 35/36) compared with all other conditions (65.5%; n = 144/220; X2 1 = 14.85; P < 0.001).

The referring professional and the triaging staff agreed on the diagnosis in 160 of the 234 cases (68.4%) in which they both submitted diagnoses (κ = 0.566; P < 0.001). When the referring professional and the triaging ophthalmology staff agreed on the diagnosis, this diagnosis was correct in 85.6% of cases (n = 137/160). When the referring professional and the triaging staff agreed on a can’t-miss diagnosis, it was correct in 100.0% of cases (n = 31/31).

This study from the Wills Eye ED found that urgent and emergent ophthalmic problems were misdiagnosed in more than one third of all referred cases. The diagnostic accuracy was significantly worse when non-eye specialists made the referrals. Reassuringly, the rate of misdiagnosis decreased when only sight- and life-threatening eye disease were analyzed; most of these cases were referred appropriately. This study underscores the limitations of ocular diagnostic accuracy in the healthcare community and highlights the usefulness of a telephone-triaging ophthalmologist in the diagnosis of urgent and emergent ocular conditions.

Footnotes

Disclosure(s): All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures form.

The author(s) have made the following disclosure(s): J.A.H.: Consultant – KalVista, Lowy Medical Research Institute, Bionic Sight LLC; Board member – Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb; Data and safety monitoring committee – Aura Bioscience, Lowy Medical Research Institute, Bionic Sight LLC

Supported by the Heed Ophthalmic Foundation (J.D.D.).

HUMAN SUBJECTS: Human subjects were included in this study. The human ethics committees at Wills Eye Hospital approved the study. All research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Individual patient-level consent was not required.

No animal subjects were included in this study.

Author Contributions:

Conception and design: Deaner, Ozzello, Zhang, Haller

Analysis and interpretation: Deaner, Amarasekera, Ozzello, Swaminathan, Bonafede, Meeker, Zhang, Haller

Data collection: Deaner, Amarasekera, Ozzello, Swaminathan, Bonafede, Meeker, Zhang, Haller

Obtained funding: Deaner, Haller; Study was performed as part of the authors' regular employment duties. No additional funding was provided.

Overall responsibility: Deaner, Amarasekera, Ozzello, Swaminathan, Bonafede, Meeker, Zhang, Haller

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Nari J., Allen L.H., Bursztyn L.L.C.D. Accuracy of referral diagnosis to an emergency eye clinic. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52(3):283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison R.J., Wild J.M., Hobley A.J. Referral patterns to an ophthalmic outpatient clinic by general practitioners and ophthalmic opticians and the role of these professionals in screening for ocular disease. BMJ. 1988;297(6657):1162–1167. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6657.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fung M., Myers P., Wasala P., Hirji N. A review of 1000 referrals to Walsall’s hospital eye service. J Public Health Oxf Engl. 2016;38(3):599–606. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Docherty G., Hwang J., Yang M. Prospective analysis of emergency ophthalmic referrals in a Canadian tertiary teaching hospital. Can J Ophthalmol. 2018;53(5):497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohammadpour M., Heidari Z., Mirghorbani M., Hashemi H. Smartphones, tele-ophthalmology, and VISION 2020. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(12):1909–1918. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2017.12.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.