Abstract

In most US health insurance markets, plans face strong incentives to “upcode” the patient diagnoses they report to the regulator, as these affect the risk-adjusted payments plans receive. We show that enrollees in private Medicare plans generate 6% to 16% higher diagnosis-based risk scores than they would under fee-for-service Medicare, where diagnoses do not affect most provider payments. Our estimates imply that upcoding generates billions in excess public spending and significant distortions to firm and consumer behavior. We show that coding intensity increases with vertical integration, suggesting a principal-agent problem faced by insurers, who desire more intense coding from the providers with whom they contract.

Diagnosis-based subsidies have become an increasingly important regulatory tool in US health insurance markets and public insurance programs. Between 2003 and 2014, the number of consumers enrolled in a market in which an insurer’s payment is based on the consumer’s diagnosed health conditions increased from almost zero to over 50 million, including enrollees in Medicare, Medicaid, and state and federal Health Insurance Exchanges. These diagnosis-based payments to insurers are known as risk adjustment, and their introduction has been motivated by a broader shift away from public fee-for-service health insurance programs and towards regulated private markets (Gruber, 2017). By compensating insurers for enrolling high expected-cost consumers, risk adjustment weakens insurer incentives to engage in cream-skimming—that is, inefficiently distorting insurance product characteristics to attract lower-cost enrollees, as in Rothschild and Stiglitz (1976).1

The intuition underlying risk adjustment is straightforward: diagnosis-based transfer payments can break the link between the insurer’s expected costs and the insurer’s expected profitability of enrolling a chronically ill consumer. But the mechanism assumes that a regulator can objectively measure each consumer’s health state. In practice in health insurance markets, regulators infer an enrollee’s health state from the diagnoses reported by physicians during their encounters with the enrollee. This diagnosis information, usually captured in bills sent from the provider to the insurer, is aggregated into a risk score on which a regulatory transfer to the insurer is based. Higher risk scores trigger larger transfers. Insurers thus have a strong incentive to “upcode” reported diagnoses and risk scores, either via direct insurer actions or by influencing physician behavior.2 By upcoding, we mean activities that range from increased provision of diagnostic services that consumers value to outright fraud committed by the insurer or provider. The extent of such practices is of considerable policy, industry, and popular interest. Nonetheless, the few recent studies examining the distortionary effects of risk adjustment (e.g., Brown et al., 2014, Carey, 2017, Einav et al., 2015, and Geruso, Layton and Prinz, 2016) have all taken diagnosis coding as fixed for a given patient, rather than as an endogenous outcome potentially determined by physician and insurer strategic behavior. In contrast, in this paper we show that endogenous diagnosis coding is an empirically important phenomenon that has led to billions in annual overpayments by the federal government, as well as significant distortions to consumer choices.

We begin by constructing a stylized model to assess the effects of upcoding in a setting where private health plans receiving risk adjustment payments compete for enrollees against a public option. We use the model to show that when risk scores (and thus plan payments) are endogenous to the contract details chosen by the private plans, three types of distortions are introduced. First, a wedge is introduced between the efficient private contract and the private contract offered in equilibrium. Equilibrium contracts are characterized by levels of coding services (and in some cases, other healthcare services) that are too high in the sense that the marginal social cost of the service exceeds the marginal social benefit. Second, the higher intensity of coding in the private plans increases government subsidies paid to these plans, which in turn increases the cost of the program to taxpayers. Third, the higher subsidies to plans with higher coding intensity lead to equilibrium plan prices that fail to reflect the underlying social resource cost of enrolling a consumer in the plan, causing consumer choices to be inefficiently tilted toward the plans that code most intensely. An important insight from our model is that these results hold whether the differential coding intensity is caused by illegal activity such as insurer fraud or by the seemingly innocuous activity of private plans offering diagnostic services at lower out-of-pocket prices than under the public option.

We investigate the empirical importance of upcoding in the context of Medicare. For hospital and physician coverage, Medicare beneficiaries can choose between a traditional public fee-for-service (FFS) option and enrolling with a private insurer through Medicare Advantage (MA). In the FFS system, most reimbursement is independent of recorded diagnoses. Payments to private MA plans are capitated with diagnosis-based risk adjustment. As illustrated by our model, although the incentive for MA plans to code intensely is strong, doing so is not costless and a plan’s response to this incentive depends on its ability to influence the providers that assign the codes. Thus, whether and to what extent coding differs between the MA and FFS segments of the market is an empirical question.

The key challenge in identifying coding intensity differences between FFS and MA, or within the MA market segment across competing insurers, is that upcoding estimates are potentially confounded by adverse selection. An insurer might report an enrollee population with higher-thanaverage risk scores either because the consumers who choose the insurer’s plan are in worse health (selection) or because for the same individuals, the plan’s benefit design and coding practices result in higher risk scores (upcoding). We develop an approach to separately identify selection and coding differences in equilibrium. The core insight of our research design is that if the same individual would generate a different risk score under two plans and if we observe an exogenous shift in the market shares of the two plans, then we should also observe changes in the market-level average of reported risk scores. Such a pattern could not be generated or rationalized by selection, because selection can affect only the sorting of risk types across insurers or plans within the market, not the overall market-level distribution of reported risk scores.3,4

To identify coding differences, we exploit large and geographically heterogeneous increases in MA enrollment within county markets that began in 2006 following the Medicare Modernization Act. We simultaneously exploit an institutional feature of the MA program that causes risk scores to be based on prior year diagnoses. This yields sharp predictions about the timing of effects relative to changing market penetration in a difference-in-differences framework. Using the rapid withincounty changes in penetration that occurred over our short panel, we find that a 10 percentage point increase in MA penetration leads to a 0.64 percentage point increase in the reported average risk score in a county. This implies that MA plans generate risk scores for their enrollees that are on average 6.4% larger in the first year of MA enrollment than what those same enrollees would have generated under FFS. Our results also suggest that the MA coding intensity differential may ratchet up over time, reaching 8.7% by the second year of MA enrollment and continuing to grow into the third year. These are large effects. A 6.4% increase in market-level risk is equivalent to 6% of all consumers in a market becoming paraplegic, 11% developing Parkinson’s disease, or 39% becoming diabetic. While these effects would be implausibly large if they reflected rapid changes to actual population health, they are plausible when viewed as reflecting only endogenous coding behavior.

To complement our main identification strategy at the market level, we also provide individual-level evidence and a second identification strategy for a sample of Massachusetts residents. We track risk scores within consumers as they transition from an employer or individual-market commercial plan to Medicare at the age 65 eligibility threshold. We present event study difference-in-differences graphs comparing the groups that eventually choose MA and FFS. We show that during the years prior to Medicare enrollment when both groups were enrolled in similar employer and commercial plans, level differences in coding intensity were stable. Following Medicare enrollment, however, the difference in coding intensity between the MA and FFS groups spike upward, providing transparent visual evidence of a coding intensity effect of MA.

These empirical findings have specific implications for the Medicare program as well as broader implications for the regulation of private insurance markets. Medicare is the costliest public health insurance program in the world and makes up a significant fraction of US government spending. Even relative to a literature that has consistently documented phenomena leading to significant overpayments to or gaming by private Medicare plans (e.g., Ho, Hogan and Scott Morton, 2014; Decarolis, 2015; Brown et al., 2014), the size of the overpayment due to manipulable coding is striking. Absent a coding correction, our estimates imply excess payments of around $10.2 billion to Medicare Advantage plans annually, or about $650 per MA enrollee per year. The excess payments, combined with external estimates of enrollment elasticities, imply that completely removing the hidden subsidy due to upcoding would reduce the size of the MA market by 17% to 33%, relative to a counterfactual in which the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) made no adjustment. In 2010, toward the end of our study period, CMS began deflating MA risk payments due to concerns about upcoding, partially counteracting these overpayments.5

We view our results as addressing an important gap in the literature on adverse selection and the public finance of healthcare. Risk adjustment is the most widely implemented regulatory response to adverse selection. A few recent studies, including Curto et al. (2014) and Einav and Levin (2014), have begun to recognize the potential importance of upcoding, but the empirical evidence is underdeveloped. The most closely related prior work on coding has shown that patients’ reported diagnoses in FFS Medicare vary with the local practice style of physicians (Song et al., 2010) and that coding responds to changes in how particular codes are reimbursed by FFS Medicare for inpatient hospital stays (Dafny, 2005; Sacarny, 2014). Ours is the first study to model the welfare implications of differential coding patterns across insurers and to provide empirical evidence of the size and determinants of these differences.

Our results also provide a rare insight into the insurer-provider relationship. Because diagnosis codes ultimately originate from provider visits, insurers face a principal-agent problem in contracting with physicians. We find that coding intensity varies significantly according to the contractual relationship between the physician and the insurer. Fully vertically integrated (i.e., provider owned) plans generate 16% higher risk scores for the same patients compared to FFS, nearly triple the effect of non-integrated plans. This suggests that the cost of aligning physician incentives with insurer objectives may be significantly lower in vertically integrated firms. These results connect to a long literature concerned with the internal organization of firms (Grossman and Hart, 1986) and the application of these ideas to the healthcare industry (e.g., Gaynor, Rebitzer and Taylor, 2004 and Frakt, Pizer and Feldman, 2013). Our results also represent the first direct evidence of which we are aware that vertical integration between insurers and providers may facilitate the “gaming” of health insurance payment systems. However, these results likewise raise the possibility that strong insurer-provider contracts may also facilitate other, more socially beneficial, objectives, including quality improvements through pay-for-performance incentives targeted at the level of the insurer. This is an issue of significant policy and research interest (e.g., Fisher et al., 2012; Frakt and Mayes, 2012; Frandsen and Rebitzer, 2014), but as Gaynor, Ho and Town (2015) describe, it is an area in which there is relatively little empirical evidence.

Finally, our results connect more broadly to the economic literature on agency problems in monitoring, reporting, and auditing. Here, insurers are in charge of reporting the critical inputs that will determine their capitation payments from the regulator. The outsourcing of regulatory functions to interested parties is not unique to this setting, with examples in other parts of the healthcare system (Dafny, 2005), in environmental regulation (Duflo, Greenstone and Ryan, 2013), in financial markets (Griffin and Tang, 2011), and elsewhere. Our results point to a tradeoff in which the tools used to better align regulator and firm incentives in one way (here, risk adjustment to limit cream-skimming) may cause them to diverge in other ways (as coding intensity is increased to capture subsidies).

2. Background

We begin by outlining how a risk-adjusted payment system functions, though we refer the reader to van de Ven and Ellis (2000) and Geruso and Layton (2017) for more detailed treatments. We then briefly discuss how diagnosis codes are assigned in practice.

2.1. Risk Adjustment Background

Individuals who are eligible for Medicare can choose between the FFS public option or coverage through a private MA plan. All Medicare-eligible consumers in a county face the same menu of MA plan options at the same prices. Risk adjustment is intended to undo insurer incentives to avoid sick, high cost patients by tying subsidies to patients’ health status. By compensating the insurer for an enrollee’s expected cost on the basis of their diagnosed health conditions, risk adjustment can make all potential enrollees—regardless of health status—equally profitable to the insurer on net in expectation, even when premiums are not allowed to vary across consumer types. This removes plan incentives to distort contract features in an effort to attract lower-cost enrollees, as in Rothschild and Stiglitz (1976) and Glazer and McGuire (2000). Risk adjustment was implemented in Medicare starting in 2004 and was fully phased-in by 2007.

Formally, plans receive a risk adjustment subsidy, Si, from a regulator for each individual i they enroll. The risk adjustment subsidy supplements or replaces premiums, p, paid by the enrollee with total plan revenues given by p + Si. In Medicare Advantage, Si is calculated as the product of an individual’s risk score, ri, multiplied by some base amount, , set by the regulator: .6 In practice in our empirical setting, is set to be approximately equal to the mean cost of providing FFS in the local county market for a typical-health beneficiary, or about $10,000 per enrollee per year on average in 2014.7

The risk score is determined by multiplying a vector of risk adjusters, xi, by a vector of risk adjustment coefficients, Λ. Subsidies are therefore . Risk adjusters, xi, typically consist of a set of indicators for demographic groups (age-by-sex cells) and a set of indicators for condition categories, which are based on diagnosis codes contained in health insurance claims. In Medicare, as well as the federal Health Insurance Exchanges, these indicators are referred to as Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCCs). Below, we refer to xi as “conditions” for simplicity. The coefficients Λ capture the expected incremental impact of each condition on the insurer’s expected costs, as estimated by the regulator in a regression of total spending on the vector xi in some reference population. Coefficients Λ are normalized by the regulator so that the average risk score is equal to 1.0 in the reference population. For Medicare Advantage payment, the reference population is FFS, and risk scores for payment in year t are based on diagnoses in t − 1. The important implicit assumption underlying the functioning of risk adjustment is that conditions, xi, do not vary according to the plan in which a consumer is enrolled. In other words, diagnosed medical conditions are properties of individuals, not individual × plan matches.

2.2. Diagnosis Coding in Practice

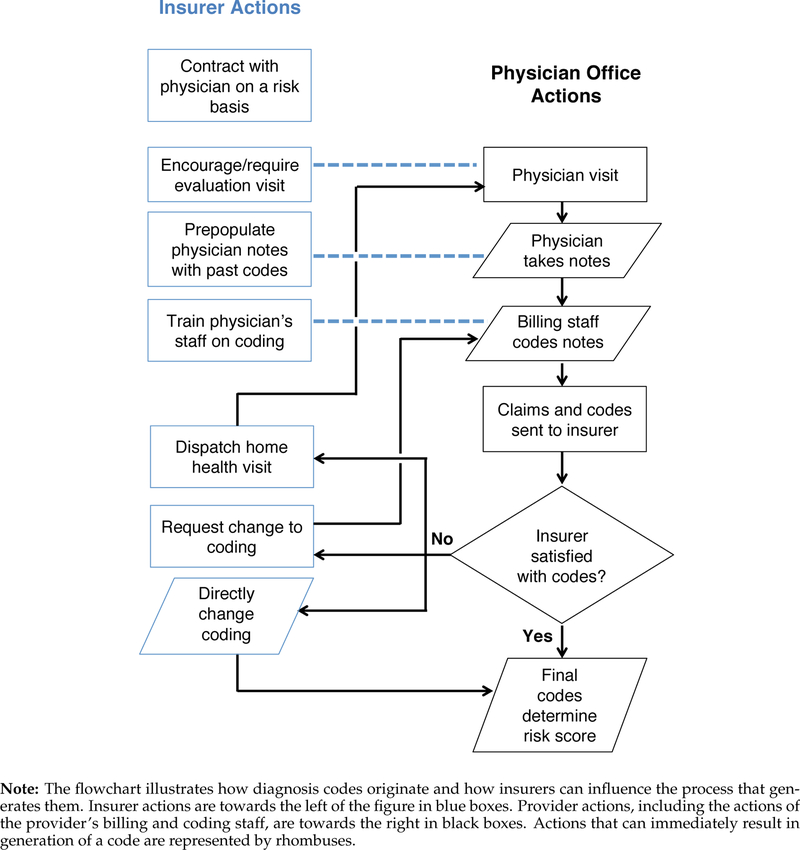

Typically, the basis for all valid diagnosis codes is documentation from a face-to-face encounter between the provider and the patient. During an encounter like an office visit, a physician takes notes, which are passed to the billing staff in the physician’s office. Billers use the notes to generate a claim, which includes diagnosis codes, that is sent to the insurer for payment. The insurer pays claims and over time aggregates all of the diagnoses associated with an enrollee. Diagnoses are then submitted to the regulator, who generates a risk score on which payments to the insurer are based.

There are many ways for plans and providers to influence the diagnoses that are reported to the regulator. Although we reserve a more complete description of these mechanisms to Appendix Section A.2 and Figure A1, we note that insurers can structure contracts with physician groups such that the payment to the group is a function of the risk-adjusted payment that the insurer itself receives from the regulator. This directly passes through coding incentives to the physician groups. Additionally, even after claims and codes are submitted to the insurer for an encounter, the insurer or its contractor may perform a chart review—automatically or manually reviewing physician notes and patient charts to add new codes that were not originally translated to the claims submitted by the submitting physician’s office. Such additions may be known only to the insurer who edits the reports sent to the regulator, with no feedback regarding the change in diagnosis being sent to the physician or her patient. Plans may also directly or indirectly encourage more diagnostic office visits to ensure that enrollees visit the doctor and have their conditions coded. Finally, insurers may proactively contact enrollees likely to have code-able conditions and send a physician or nurse to the enrollee’s home with the sole purpose of coding the relevant, reimbursable diagnoses for the current plan year. As we discuss in Section 8, this issue is of particular concern to the Medicare regulator, CMS, as these visits, often performed by third-party contractors, appear to often be unmoored from any follow-up care or even communication with the patient’s normal physician.

None of the insurer activities targeted at diagnosis coding take place in FFS because providers under the traditional system are paid directly by the government, and the basis of these payments outside of hospital settings is procedures, not diagnoses. This difference in incentive structure between FFS and MA makes Medicare a natural setting for studying the empirical importance of differential coding intensity.

3. Model of Risk Adjustment with Endogenous Coding

In this section, we present a stylized model of firm behavior in a competitive insurance market where payments are risk adjusted. The model illustrates how distortions to public spending, consumers’ plan choices, and insurers’ benefit design can arise if risk scores are endogenous to a plan’s behavior.

3.1. Setup

We consider an insurance market similar to Medicare, where consumers choose between a public option plan (FFS) and a uniform private plan alternative offered by insurers in a competitive market (MA). An MA plan consists of two types of services and a price: {δ, γ; p}. Coding services, δ, include activities like insurer chart review. These services affect the probability that diagnoses are reported. We also allow them to impact patient utility. All other plan details are rolled up into a composite healthcare service, γ. We allow that any healthcare service or plan feature may impact reported diagnoses. For example, zero-copay specialist visits may induce some consumer moral hazard and alter the probability that a consumer visits a specialist and thus influence the probability that a marginal (correct) diagnosis is recorded.8 Services δ and γ are measured in the dollars of cost they impose on the MA plan.

Denote the consumer valuations of δ and γ in dollar-metric utility as v(δ) and w(γ), respectively. We assume utility is additively separable in v and w with vʹ > 0, wʹ > 0, vʺ < 0, and wʺ < 0. The FFS option offers reservation utility of for the mean consumer. Its price is zero. A taste parameter, σi, which is uncorrelated with costs net-of-risk adjustment, distinguishes consumers with idiosyncratic preferences over the MA/FFS choice. The purpose of the assumption of orthogonality between the taste parameter and costs is to simplify the exposition of the consequences of upcoding. The conclusions we draw from this stylized model do not rely on this assumption.9 Utility of the MA plan is thus v(δ)+w(γ)+σi. Using ζi to capture mean zero ex ante health risk that differs across consumers, expected costs in MA are ci, MA = δ + γ + ζi.

To narrow focus here on the distortions generated by upcoding even when risk adjustment succeeds in perfectly in counteracting selection, we make two simplifying assumptions. First, we assume that consistent with the regulatory intent of risk adjustment, there is no uncompensated selection after risk adjustment payments are made: Risk adjustment payments net out idiosyncratic health risk in expectation, allowing us to ignore the mean zero ζi term when considering firm incentives. Expected (net) marginal costs are equal to expected (net) average costs and are δ + γ. To simplify exposition, we assume further that there is no sorting by health status across plans in equilibrium. This implies that the mean risk score within the MA plan is 1.10

MA plans charge a premium p and receive a per-enrollee subsidy, Si, that is a function of the risk score, ri, MA, the plan reports. Following the institutional features of Medicare, , where is a base payment equal to the cost of providing FFS to the typical health Medicare beneficiary in the local market. Defining ρi(δ, γ) ≡ ri, MA − ri, FFS as the difference between the risk score each beneficiary would have generated in MA relative to the risk score she would have generated in FFS, the average (per capita plan-level) MA subsidy is then . This simplifies to if we assume, counter to the empirical facts we document, that risk scores are fixed properties of individuals and invariant to MA enrollment.

3.2. Planner’s Problem

To illustrate how the competitive equilibrium may yield inefficiencies, consider as a benchmark a social planner who is designing an MA alternative to FFS, and whose policy instruments include δ, γ, and the supplemental MA premium p. The planner takes as given the cost, zero price, and reservation utility of the FFS option, though we return to the issue of the social cost of FFS further below.11 The planner maximizes consumer utility generated by MA plan services, net of the resource cost of providing them:

| (1) |

First order conditions with respect to γ and δ yield v’(δ∗) = 1 and w’(γ∗) = 1. At the optimal provision of healthcare services and the optimal investment in coding, the marginal consumer utility of γ and δ equal their marginal costs, which is 1 by construction.

Next consider the price p∗ that efficiently allocates consumers to the FFS and MA market segments. In an efficient allocation, consumers choose the MA plan if and only if the social surplus generated by MA for them exceeds the social surplus generated by FFS.12 This condition is

| (2) |

A consumer chooses MA only if her valuation of MA minus the premium exceeds her reservation utility in the FFS option at its zero price: . This criterion for a consumer choosing MA matches the efficient allocation condition in (2) if . Therefore, the planner sets the MA/FFS price difference equal to the difference between resources consumed under MA (δ+γ) versus under FFS . This is the familiar result that (incremental) prices set equal to (incremental) marginal costs induce efficient allocations.

3.3. Insurer Incentives and Coding in Equilibrium

We next consider an MA insurer who sets {δ, γ; p} in a competitive equilibrium. Because consumer preferences are identical up to a taste-for-MA component that is uncorrelated with δ and γ and is uncorrelated with costs net of risk adjustment, there is a single MA plan identically offered by all insurers in equilibrium. Insurers will offer the contract that maximizes consumer surplus subject to the zero-profit condition, or else face zero enrollment. The zero profit condition here is p+S = δ+γ. As described above, subsidies are a function of the level of healthcare and coding services chosen by the plan: . The insurer’s problem, which simplifies to maximizing consumer surplus, is then

| (3) |

where we have substituted marginal costs net of the subsidy for the price using the zero profit condition. The first-order conditions yield and . If risk scores were exogenous to δ and γ and fixed at their FFS level, then and S would amount to a lump sum subsidy. In this case service provision would be set to the socially optimal level in a competitive equilibrium, with and . Additionally, the competitive equilibrium MA premium would equal the premium that efficiently sorts consumers between MA and FFS: . Efficient plan design and pricing would be achieved.

Generally, however, when the subsidy is endogenous to γ and δ, inefficiencies will arise. Given diminishing marginal utility of δ and γ, and assuming that more coding services and more healthcare services lead to higher risk scores, competition under endogenous risk scores induces MA insurers to set the levels of both healthcare spending and coding inefficiently high: and . This is because on the margin, insurers are rewarded via the subsidy for setting service provision above the level implied by the tradeoff between satisfying consumer preferences and incurring plan costs. The intuition here is the standard public finance result that taxes or subsidies that are responsive to an agent’s behaviors induce inefficient behaviors relative to the first best. We show in Appendix Section A.4 that identical distortions arise in the incentives for setting δ and γ in an imperfectly competitive market with endogenous coding. Given the first order conditions above, the competitive equilibrium premium will be equal to because the zero profit condition forces the additional subsidy to be passed through to the consumer as a lower premium. This price below marginal cost induces inefficient sorting, tilting consumer choices towards MA.

3.4. Welfare

Although we do not estimate the welfare impacts of upcoding in this paper, modeling welfare is instructive for understanding the implications of the coding differences we identify. To build up a welfare expression, let θMA and θFFS denote the fraction of the Medicare market enrolled in the MA and FFS segments, respectively, with . Here, θFFS expresses the fraction of the population for whom idiosyncratic preferences for MA, σ ∼ F(·), are less than the mean difference in consumer surplus generated by FFS at its zero price relative to the MA alternative at its price p(δ, γ). MA’s market share is simply 1 − θFFS. Let ΦMA and ΦFFS tally the per-enrollee social surplus generated by each option, excepting the idiosyncratic taste component, σ.13

Welfare is the social surplus generated for enrollees in each of the MA and FFS market segments minus the distortionary cost of raising public funds to subsidize (both segments of) the market. Using tildes to indicate the competitive equilibrium outcomes with endogenous risk scores, equilibrium social surplus per capita is

| (4) |

where the integral term accounts for the variable component of surplus generated by idiosyncratic tastes for MA among those who enroll in MA. The last term captures the distortionary cost of financing Medicare. It is the government’s expenditure on FFS plus its expenditure on MA, multiplied by the excess burden of raising public funds, κ. Taking per capita FFS costs, , as given and assuming that the levels of δ and γ chosen by the MA plans generate risk scores that exceed the FFS risk scores, public spending on the Medicare program increases for every consumer choosing MA instead of FFS. Without differential coding, FFS and MA risk scores are the same (ρ = 0) and the public funds term would reduce to , which is not a function of the share of beneficiaries choosing MA.

Next consider the welfare loss associated with endogenous coding by comparing the social surplus in (4) to a (possibly infeasible) regime in which risk scores are exogenously determined and service levels are optimally set. With defined as above, let WExo denote the social surplus per capita in a competitive equilibrium in which risk scores are exogenous to plan choices, which we show above replicates the social planner’s solution in the same setting. Using stars to indicate plan features (δ∗, γ∗) and market outcomes (θ∗, Φ∗) in the case of first best service levels and exogenously determined subsidies that do not depend on those levels, this difference is

| (5) |

The expression, derived in Appendix A.5, reveals three sources of inefficiency that arise from linking the MA subsidy to risk scores that plans can influence: (i) a subsidy “overpayment” to MA plans that is not balanced by a reduction in FFS spending, thus expanding overall spending on the Medicare program and the consequent public funds cost; (ii) an allocative inefficiency in which consumers sort to the wrong FFS vs MA market segment because the MA prices are distorted; and (iii) a resource use inefficiency in which plans over-invest in services that affect risk scores relative to the value of these plan features to consumers.

Although we are not able to estimate the necessary parameters for assessing the extent of each of the three inefficiencies, our estimation recovers , the differential coding intensity in MA relative to FFS, which is an input to term (i). Because the base payment and the fraction of the market in MA are quantities that are directly observable, we can calculate term (i) after recovering . We do this in Section 8.1. Note that estimating term (i) does not require us to pin down the mechanism behind the MA/FFS coding difference. It requires only generating an unbiased estimate of the difference itself. Note also that this quantity reflects the difference between actual MA coding and FFS coding, not the difference between actual MA coding and optimal MA coding, ρ(δ∗, γ∗), which too could differ from FFS coding.14

Term (ii) is a function of how many consumers choose MA in equilibrium relative to the first best: . In Section 8.2 we combine our estimates of ρ with parameters from the MA literature to calculate how different the size of the MA market would be relative to what we observe if the differential MA subsidy to coding were removed. This sheds some light on the size of the distortion in (ii).

Term (iii) reveals that even if consumers place positive value on the marginal coding services provided by plans (i.e., ), there is a welfare loss with endogenous risk scores because the incremental valuation of the coding services is less than the incremental social cost . Insurers don’t internalize the full social cost of these services because the subsidy partially compensates them for coding-related activities at a rate .

Because our empirical strategy is not designed to recover consumer preferences over healthcare services, we cannot estimate term (iii). The term nonetheless provides useful intuitions in interpreting our results. For example, it implies that inefficiencies may also arise in the provision of non-coding services such as annual wellness visits and lab tests if these have incidental impacts on the probability that a diagnosis is captured. In the controversial case of MA home health risk assessments, even if home visits provide value to enrollees, such valuations are likely to fall below the social cost of provision and would not have been included in plans if insurers were responding only to consumer preferences over healthcare services. Likewise, it is possible in principle that consumers get value out of intensive coding, perhaps because physicians have more information about their conditions and can thus provide better treatment. The model shows that while improved coding may be valued by consumers, profit maximization implies that in equilibrium its value will be exceeded by its (social resource) cost, so the additional coding is inefficient.

Equation (5) also informs how the government, as an actor, may or may not address the specific inefficiencies caused by the coding incentive. The primary strategy currently used by regulators to address the implicit MA overpayment is to deflate private plan risk scores by some factor before determining payments. If risk scores were reduced by an amount η set equal to ρ, then the additional cost of public funds (term i), could be eliminated. However, this would not eliminate welfare losses due to inefficient sorting (term ii), as the new net-of-subsidy MA price still would not accurately reflect the differential cost of FFS vs. MA. Risk score deflation also would not eliminate surplus losses due to inefficient contracts (term iii) because the insurer’s marginal incentives to code intensely would not be changed by subtracting a fixed term from the subsidy.15,16

Finally, we note that the welfare analysis here is relative to a first best in a setting with exogenously determined subsidies. It assumes away other distortions in the MA market that affect prices and the design of plan services. Although our focus is on the specific distortions generated by the coding incentive, these are just one piece in the broader landscape of efficiency and welfare in the MA program, and a complete second best analysis must account for other simultaneous market failures.

3.5. Upcoding, Complete Coding, and Socially Efficient Coding

Motivated by the model, we define upcoding in MA as the difference between the risk score a consumer would receive if she enrolled in an MA plan and the score she would have received had she enrolled in FFS: ρi(δ, γ) ≡ ri, MA − ri, FFS. It is simply the differential coding intensity between FFS and MA, which maps to the first source of inefficiency documented in Equation (5). It is the parameter required to measure the excess spending (and, therefore the excess burden) associated with a consumer choosing MA in place of FFS.

As an alternative benchmark, one could define upcoding as many physicians do: the difference between a reported risk score and the risk score that would be assigned to an individual if coding were “complete” in the sense that the individual was objectively examined and all conditions were recorded. Even setting aside the practical and conceptual difficulties with such a definition,17 our model highlights that such a benchmark of “complete” coding ignores the social resource costs of the coding, a key component of social welfare. This highlights an important distinction between the economist’s and physician’s view of this phenomenon.

4. Identifying Upcoding in Selection Markets

The central difficulty of empirically identifying upcoding arises from selection on risk scores. At the health plan level, average risk scores can differ across plans competing in the same market either because coding differs for identical patients, or because patients with systematically different health conditions select into different plans. Our solution to the identification problem is to focus on market level averages of risk scores, rather than plan risk scores. Whereas the reported risk composition of plans can reflect both coding differences and selection, risk scores calculated at the market level will not be influenced by selection—that is, by how consumers sort themselves across plans within the market. We show in this section that changes in risk scores at the market level that result from consumers shifting between plans within the market identify differences in coding.

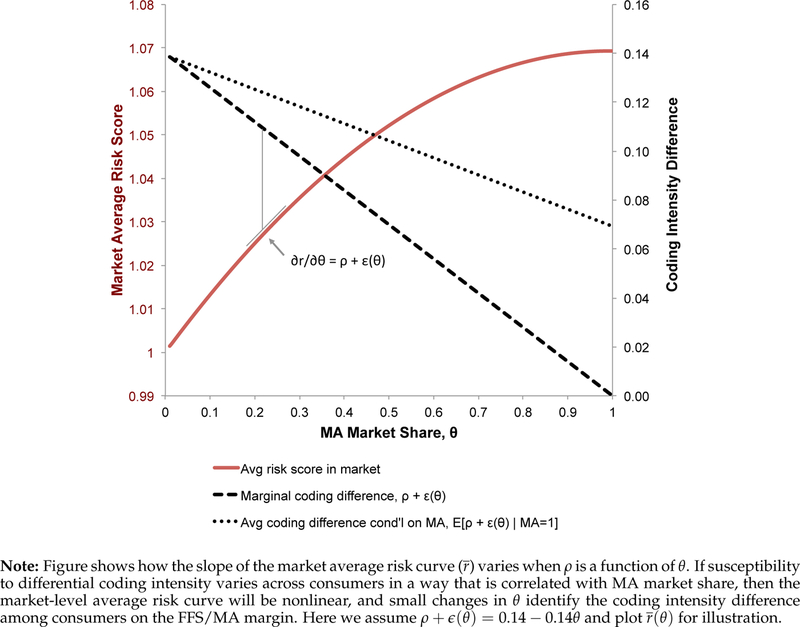

To see this, consider how the mean risk score in a county changes as local Medicare beneficiaries shift from FFS to MA. Define the risk score an individual would have received in FFS as . Define the same person’s risk score had they enrolled in MA as , where is the mean coding intensity difference between MA and FFS across all i and where we allow for individual-level heterogeneity in the difference between MA and FFS risk scores as captured by ei. Using as the indicator function for choosing MA, an individual’s realized risk score is then . Let ϵ(θ) be the average value of ei for the set of consumers on the MA/FFS margin when the MA enrollment share equals θ. The county-level mean risk score as a function of MA enrollment can thus be written as , where expresses the unconditional expectation of . The integral measures the mean MA/FFS coding difference among the types choosing MA. In the simple case of no individual heterogeneity in the size of the coding effect, and the derivative of the county-level risk score with respect to changes in MA share exactly pins down the difference in coding intensity. That is, . In the more complex case in which there is arbitrary heterogeneity in ϵi, the slope identifies not the mean differential coding intensity across all i, which is , but rather the coding difference for the marginal consumers generating the change in market share. (See Appendix A.7.)

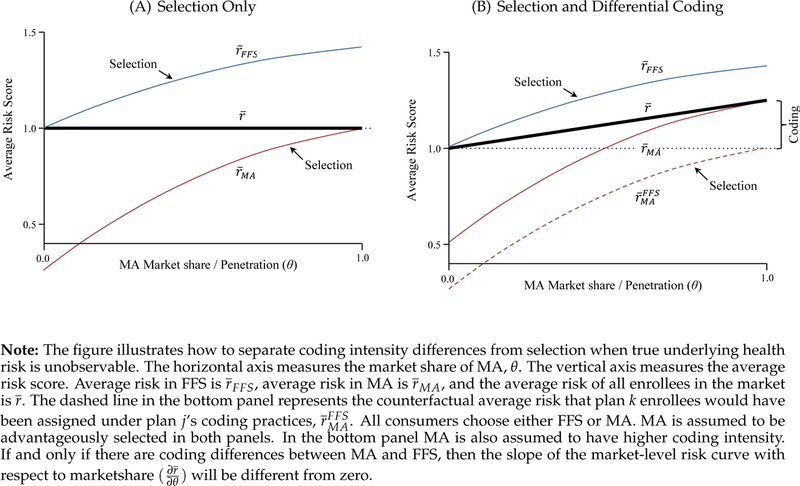

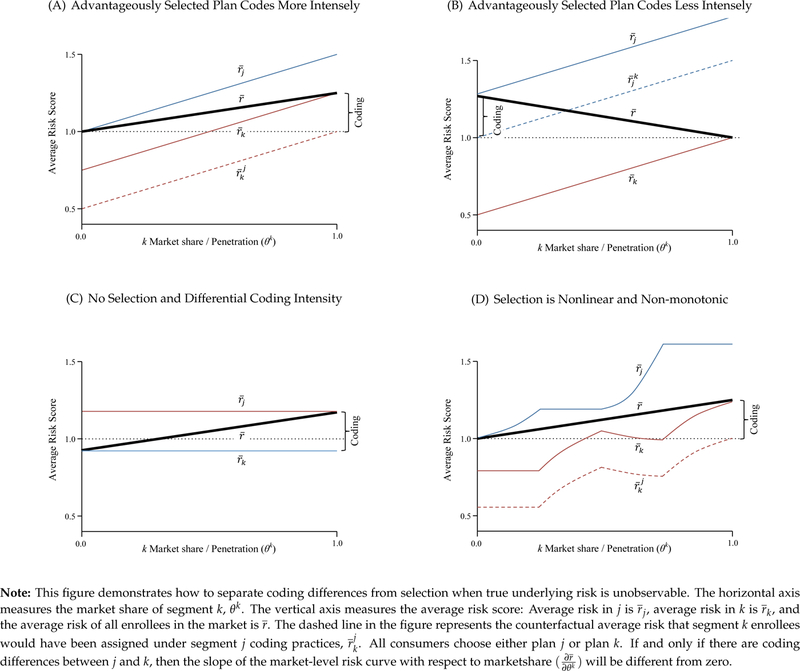

Figure 1 provides a graphical intuition of this idea for the simple case of a constant additive effect of MA enrollment on risk scores. We depict two market segments that are intended to align with FFS and MA, though the intuitions apply to considering coding differences across MA plans within the MA market segment as well. In the figure, all consumers choose either FFS or MA. The market share of MA increases along the horizontal axis. The MA segment is assumed to be advantageously selected on risk scores, so that the risk score of the marginal enrollee is higher than that of the average enrollee. Thus, the average risk within the MA segment is lower at lower levels of θMA.18

Figure 1:

Identifying Coding Differences in Selection Markets

In the top panel of Figure 1, we plot the baseline case of no coding differences across plans . The top panel shows three curves: the average risk in FFS , the average risk in MA , and the average risk of all enrollees in the market . As long as there is no coding difference between the plans or market segments, the market-level risk , which is averaged over all enrollees, is constant as θ changes. This is because reshuffling enrollees across plan options within a market does not affect the market-level distribution of underlying health conditions. Nor does it affect risk scores if the mapping from health to recorded diagnoses does not vary with plan choice (which is by assumption here). In the bottom panel of Figure 1 we add differential coding. For reference, the dashed line in the figure represents the counterfactual average risk that MA enrollees would have been assigned under FFS coding intensity, . The key difference in the bottom panel is that if MA/FFS coding intensity differs, then market-level risk changes as a function of MA’s market share. This is because even if the population distribution of actual health conditions is fixed, market-level reported risk scores would change as market shares shift between plans with higher and lower coding intensity. As the marginal consumer switches from FFS to MA, she increases θMA by a small amount and simultaneously increases the average reported risk in the market by a small amount (by moving to a plan that assigns her a higher score). Thus the slope identifies . We estimate this slope in the empirical exercise that follows.

We show in Appendix A.7 that the core intuition of Figure 1 holds if we relax many of our assumptions, including additive baseline risk and the direction and monotonicity of selection. Additionally, we show that when heterogeneity in risk is correlated with θ, estimates of are “local,” identifying the average coding difference across the set of consumers who are marginal to the variation in MA penetration used in estimation, analogous to the treatment on the treated. As explained in Appendix A.7, this local estimate is, conveniently, likely to be the parameter of interest for determining excess public spending.

5. Setting and Empirical Framework

5.1. Data

Estimating the slope requires observing market-level risk scores as MA penetration changes. We obtained yearly county-level averages of risk scores and MA enrollment by plan type from CMS for 2006 through 2011.19 MA enrollment is defined as enrollment in any MA plan type, including managed care plans like Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) and Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs), private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans, and employer MA plans. In our main specifications, we consider the Medicare market as divided between the MA and FFS segments and collapse all MA plan types together. We later estimate heterogeneity in coding within MA, across its various plan type components. MA penetration (θMA) is the fraction of all beneficiary-months of a county-year spent in an MA plan. Average risk scores are weighted by the fraction of the year each beneficiary was enrolled in Medicare.

All analysis of risk scores in the national sample is conducted at the level of market averages, as the regulator does not generally release individual-specific risk adjustment data for MA plans. We supplement these county-level aggregates with administrative data on demographics for the universe of Medicare enrollees from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) for 20062011. These data allow us to construct county-level averages of the demographic (age and gender) component of risk scores, which we use in a falsification test.

Table 1 displays summary statistics for the balanced panel of 3,128 counties that make up our analysis sample. The columns compare statistics from the introduction of risk adjustment in 2006 through the last year for which data are available, 2011. These statistics are representative of counties, not individuals, since our unit of analysis is the county-year. The table shows that risk scores, which have an overall market mean of approximately 1.0, are lower within MA than within FFS, implying that MA selects healthier enrollees.20 Table 1 also shows the dramatic increase in MA penetration over our sample period, which comprises one part of our identifying variation.

Table 1:

Summary Statistics

| Analysis Sample: Balanced Panel of Counties, 2006 to 2011 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2011 | ||||

| Mean | Std. Dev | Mean | Std. Dev | Obs | |

| MA penetration (all plan types) | 7.1% | 9.1% | 16.2% | 12.0% | 3128 |

| Risk (HMO/PPO) plans | 3.5% | 7.3% | 10.5% | 10.5% | 3128 |

| PFFS plans | 2.7% | 3.2% | 2.7% | 3.7% | 3128 |

| Employer MA plans | 0.7% | 2.2% | 2.8% | 4.3% | 3128 |

| Other MA plans | 0.2% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3128 |

| MA-Part D penetration | 5.3% | 8.0% | 13.1% | 10.8% | 3128 |

| MA non-Part D penetration | 1.8% | 3.0% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 3128 |

| Market risk score | 1.000 | 0.079 | 1.000 | 0.085 | 3128 |

| Risk score in TM | 1.007 | 0.082 | 1.003 | 0.084 | 3128 |

| Risk score in MA | 0.898 | 0.171 | 0.980 | 0.147 | 3124 |

Note: The table reports county-level summary statistics for the first and last year of the main analysis sample. The sample consists of 3,128 counties for which we have a balanced panel of data on Medicare Advantage penetration and risk scores. MA penetration in the first row is equal to the beneficiary-months spent in Medicare Advantage divided by the total number of Medicare months in the county × year. The market risk score is averaged over all Medicare beneficiaries in the county and normed to 1.00 nationally in each year.

5.2. Identifying Variation

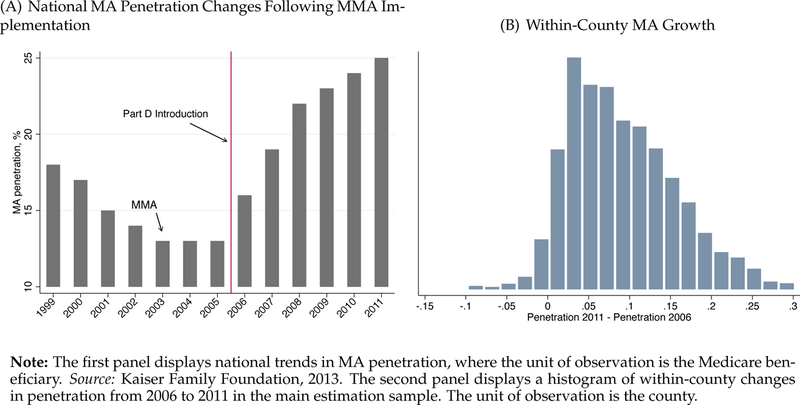

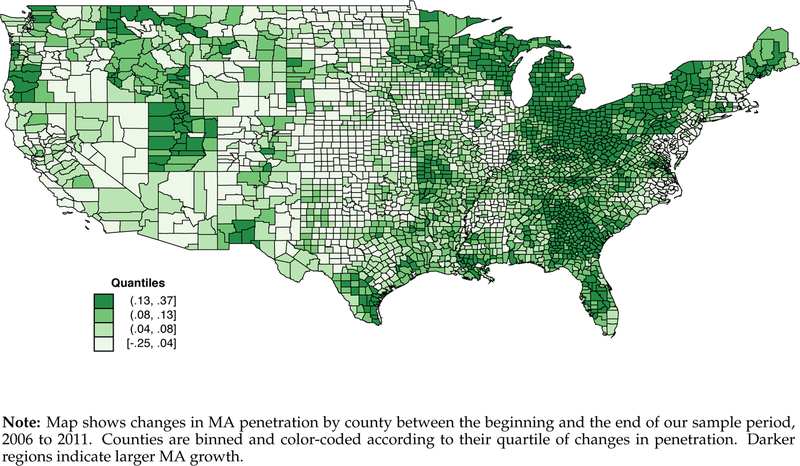

We exploit the large and geographically heterogeneous increases in MA penetration that followed implementation of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. The Act introduced Medicare Part D, which was implemented in 2006 and added a valuable new prescription drug benefit to Medicare. Because Part D was available solely through private insurers and because insurers could combine Part D drug benefits and MA insurance under a single contract, this drug benefit was highly complementary to enrollment in MA. Additionally, MA plans were able to “buy-down” the Part D premium paid by all Part D enrollees. This, along with increases in MA benchmark payments in some counties, led to fast growth in the MA market segment (Gold, 2009). In Panel A of Figure 2, we put this timing in historical context. Following a period of decline, MA penetration doubled nationally between 2005 and 2011. Panel B of the figure shows that within-county penetration changes were almost always positive, though the size of these changes varied widely. A map of changes by county, presented in Figure A3, shows that this MA penetration growth was not limited to certain regions or to urban or rural areas.

Figure 2:

Identification: Within-County Growth in Medicare Advantage Penetration

Our main identification strategy relies on year-to-year variation in penetration within geographic markets to trace the slope of the market average risk curve, . The identifying assumption in our difference-in-differences framework is that year-to-year growth in MA enrollment within counties did not track year-to-year variation in the county’s actual population-level health. The assumption is plausible because the incidence of the types of chronic conditions used in risk scoring (such as diabetes and cancer) is unlikely to change sharply year-to-year. In contrast, reported risk can change sharply due to coding differences as the local Medicare population shifts to MA. In support of the identifying assumption, we show that there is no correlation between within-county changes in θMA and within-county changes in a variety of demographic, morbidity, and mortality outcomes that could in principle signal health-motivated demand shifts.

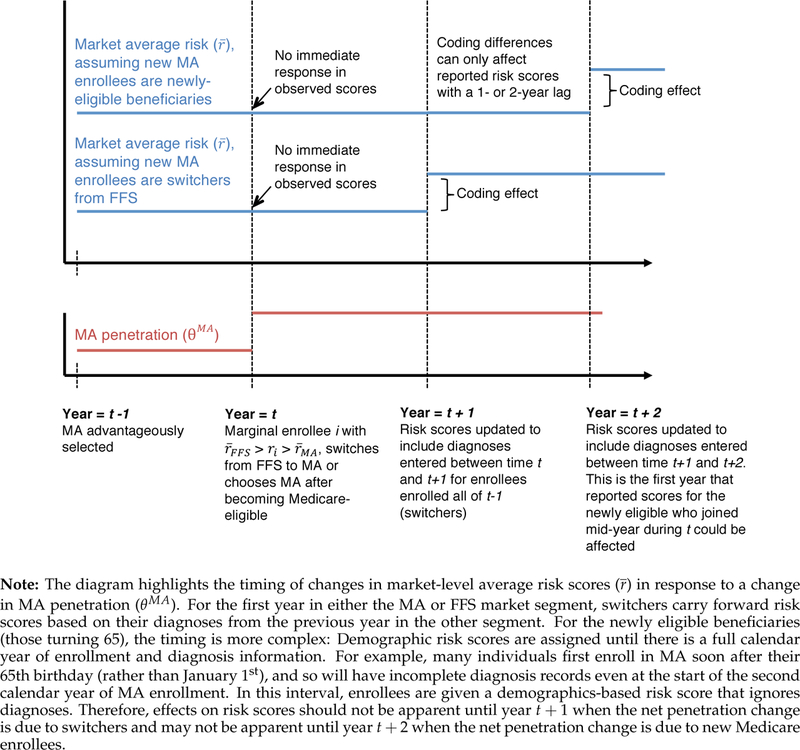

We also exploit an institutional feature of how risk scores are calculated in MA to more narrowly isolate the identifying variation. Under Medicare rules, the risk scores that are assigned to beneficiaries and used as a basis for payment in calendar year t are based on diagnoses derived from service provision in calendar year t − 1. This implies, for example, that if an individual moves to MA from FFS during open enrollment in January of a given year, the risk score for her entire first year in MA will be based on diagnoses she received while in FFS during the prior calendar year. Only after the first year of MA enrollment will the risk score of the switcher include diagnoses she received while enrolled with her MA plan. Changes in risk scores due to upcoding should therefore not occur in the same year as the identifying shift in enrollment. We test this.

5.3. Econometric Framework

We estimate difference-in-differences models of the form:

| (6) |

where is the average market-level risk in county c of state s in year t, and θMA denotes MA penetration, which ranges from zero to one. County and year fixed effects are captured by γc and γt, so that effects β are identified within counties over time. County fixed effects control for any unobserved constant local factors that could simultaneously affect population health and MA enrollment, such as medical infrastructure, consumer health behaviors, or physician practice styles (Song et al., 2010; Finkelstein, Gentzkow and Williams, 2016). Year fixed effects are included to capture any changes in the composition of Medicare at the national level. Xsct is a vector of time-varying county characteristics described in more detail below. The subscript τ in the summation indicates the timing of the penetration variable, θ, relative to the timing of the reported risk score. This specification allows flexibility in identifying the timing of effects. Coefficients βτ multiply contemporaneous MA penetration (τ = t), leads of MA penetration (τ > t), and lags of MA penetration (τ < t). Contemporaneous and leading βs serve as placebo tests, revealing whether counties were differentially trending in the dependent variable prior to when risk scores could have plausibly been affected by upcoding.

The coefficient of interest is βt−1 because of the institutional feature described above in which risk scores are calculated based on the prior full year’s medical history, so that upcoding could plausibly affect risk scores only after the first year of MA enrollment. A positive coefficient on lagged penetration indicates more intensive coding in MA relative to FFS.

6. Results

6.1. Main Results

Table 2 reports our main results. The coefficient of interest is on lagged MA penetration. In column 1, we present estimates of the baseline model controlling for only county and year fixed effects. The difference-in-differences coefficient indicates that the market-level average risk score in a county increases by about 0.07—approximately one standard deviation—as lagged MA penetration increases from 0% to 100%. Because risk scores are scaled to have a mean of one, this implies that an individual’s risk score in MA is about 7% higher than it would have been under fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare. In column 2, we add linear state time trends, and in column 3, we add time-varying controls for county demographics.21 Across specifications, the coefficient on lagged MA penetration is stable.22

Table 2:

Main Results: Impacts of MA Expansion on Market-Level Reported Risk

| Dependent Variable: County-Level Average Risk Score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| MA Penetration t (placebo) | 0.007 (0.015) |

0.001 (0.019) |

0.001 (0.019) |

0.006 (0.017) |

| MA Penetration t-1 | 0.069** (0.011) |

0.067** (0.012) |

0.064** (0.011) |

0.041** (0.015) |

| MA Penetration t-2 | 0.046* (0.022) |

|||

| Main Effects | ||||

| County FE | X | X | X | X |

| Year FE | X | X | X | X |

| Additional Controls | ||||

| State X Year Trend | X | X | X | |

| County X Year Demographics | X | X | ||

| Mean of Dep. Var. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Observations | 15,640 | 15,640 | 15,640 | 12,512 |

Note: The table reports coefficients from difference-in-differences regressions in which the dependent variable is the average risk score in the market (county). Effects of contemporaneous (t) and lagged (t − 1, t − 2) Medicare Advantage (MA) penetration are displayed. Because MA risk scores are calculated using diagnosis data from the prior plan year, changes in MA enrollment can plausibly affect reported risk scores via differential coding only with a lag. Thus, contemporaneous penetration acts as a placebo test. Observations are county × years. The inclusion of an additional lag in column 4 reduces the available panel years and the sample size. All specifications include county and year fixed effects. Column 2 additionally controls for state indicators interacted with a linear time trend. Columns 3 and 4 additionally control for the demographic makeup of the county × year by including 18 indicator variables capturing the fraction of the population in 5-year age bins from 0 to 85 and >85. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the county level.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

An alternative interpretation of these results is that, contrary to our identifying assumption, the estimates reflect changes in underlying health in the local market. Although we cannot rule out this possibility entirely, the coefficient estimates for the contemporaneous MA penetration variable, reported in the first row of Table 2, constitute a kind of placebo test. If there were a contemporaneous correlation between MA penetration changes and changes in risk scores, it would suggest that the health of the population was drifting in a way that was spuriously correlated with the identifying variation. Contrary to this, the placebo coefficients are very close to zero and insignificant across all specifications. Effects appear only with a lag, consistent with the institutions described above.23

As discussed above, switchers from FFS to MA carry forward their old FFS risk scores for their first MA plan year. For newly-eligible consumers aging into Medicare at 65 and choosing MA, the timing is more complex. Diagnosis-based risk scores may not be assigned until after two calendar years with MA enrollment due to the details of how new enrollees are treated by the risk adjustment system.24 To investigate, in column 4 of Table 2 we include a second lag of θ in the regression. Each coefficient represents an independent effect, so that point estimates in column 4 indicate a cumulative upcoding effect of 8.7% (=4.1+4.6) after two years. The timing is consistent with some of the changes in θ being driven by newly-eligible beneficiaries. It is also consistent with the possibility that even among switchers, for whom effects could begin to be seen after one year of enrollment, coding intensity differentials ratchet up over the time a beneficiary stays with an MA plan (Kronick and Welch, 2014). This is plausible, as some insurer strategies for increasing coding intensity, such as prepopulating physician notes with past years’ diagnoses, require a history of contact with the patient.

To put the size of our main estimate in context, a 6.4% increase in market-level risk (Table 2, column 3) would be associated with 6% of all consumers in a market becoming paraplegic, 11% developing Parkinson’s disease, or 39% becoming diabetic. The effects we estimate would be implausibly large if they reflected true (high frequency) changes in underlying population health, rather than coding activity.

6.2. Falsification Tests

As further support of the identifying assumption, in Table 3 we conduct a series of falsification tests intended to uncover any correlation between changes in MA penetration and changes in other timevarying county characteristics not plausibly affected by upcoding. Each column in the table replicates specifications from Table 2, but with alternative dependent variables. In columns 1 and 2, the dependent variable is the demographic portion of the risk score. The demographic portion of the risk score is based only on age and gender, with this information retrieved from the Social Security Administration rather than reported by the plan. Both the lagged and contemporaneous coefficients are near zero and insignificant, showing no correlation between MA penetration and the portion of the risk score that is exogenous to insurer and provider actions.25

Table 3:

Falsification Tests: Effects on Measures Not Manipulable by Coding

| Ependent Variable, Calculated as County Average: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Portion of Risk Score |

Mortality Over 65 |

Cancer Incidence Over 65 |

||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| MA Penetration t | 0.001 (0.002) |

0.001 (0.002) |

0.002 (0.002) |

0.002 (0.003) |

−0.005 (0.005) |

−0.005 (0.005) |

| MA Penetration t-1 | 0.000 (0.002) |

−0.001 (0.002) |

−0.002 (0.002) |

−0.002 (0.002) |

0.001 (0.004) |

0.003 (0.005) |

| Main Effects | ||||||

| County FE | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Year FE | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Additional Controls | ||||||

| State X Year Trend | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| County X Year Demographics | X | X | X | |||

| Mean of Dep. Var. | 0.485 | 0.485 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| Observations | 15,640 | 15,640 | 15,408 | 15,408 | 3,050 | 3,050 |

Note: The table reports estimates from several falsification exercises in which the dependent variables are not in principle manipulable by coding activity. The coefficients are from difference-in-differences regressions of the same forms as those displayed in Table 2, but in which the dependent variables are changed, as indicated in the column headers. In columns 1 and 2, the dependent variable is the average demographic risk score in the county-year, calculated by the authors using data from the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File based on age, gender, and Medicaid status, but not diagnoses. In columns 3 and 4, the dependent variable is the mortality rate which is derived using data from the National Center for Health Statistics. In columns 5 and 6, the dependent variable is the cancer incidence rate from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute, which tracks cancer rates independently from rates observed in claims data. The smaller sample size in columns 3 and 4 is due to the NCHS suppression of small cells. The smaller sample size in columns 5 and 6 reflects the incomplete geographical coverage of SEER cancer incidence data. Cancer incidence and mortality are both calculated conditional on age ≥ 65. Observations are county × years. Controls are as described in Table 2. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the county level.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

In columns 3 through 6 of Table 3, we test whether changes in MA penetration are correlated with independent (non-insurer reported) measures of mortality and morbidity. Mortality is independently reported by vital statistics. For morbidity, finding data that is not potentially contaminated by the insurers’ coding behavior is challenging. The typical sources of morbidity data are the medical claims reported by insurers. Here we rely on cancer incidence data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute, which operates an independent data collection enterprise to determine diagnoses. Cancer data is limited to the subset of counties monitored by SEER, which accounted for 27% of the US population in 2011 and 25% of the population over 65. In columns 3 and 4, the dependent variable is the county × year mortality rate among residents age 65 and older. In columns 5 and 6, it is the SEER-reported cancer incidence in the county × year among residents age 65 and older. Across all of the outcomes in Table 3, coefficients on contemporaneous and lagged MA penetration are consistently close to zero. In Table A5 we show that similar results hold when the dependent variables are various measures of the Medicare age structure in the county × year. Each falsification test supports the assumption that actual county population health was not changing in a way that was correlated with our identifying variation.

6.3. Heterogeneity and Provider Integration

Because diagnoses originate with providers rather than insurers, insurers face an agency problem regarding coding. Plans that are provider-owned, selectively contract with physician networks, or follow managed care models (i.e., HMOs and PPOs) may have more tools available for influencing provider coding patterns. For example, our conversations with MA insurers and physician groups indicated that vertically integrated plans often pay their physicians (or physician groups) partly or wholly as a function of the risk score that physicians’ diagnoses generate. Within large physician groups, leadership may further transmit this incentive to individuals by placing pressure on low scoring physicians to bring their average risk scores into line with the group. Integration, broadly defined as the strength of the contract between insurers and providers, could therefore influence a plan’s capacity to affect coding.

To investigate this possibility, in Table 4 we separate the effects of market share increases among HMO, PPO, and private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans. HMOs may be the most likely to exhibit integration, followed by PPOs. PFFS plans are fundamentally different. During most of our sample period, PFFS plans did not have provider networks. Instead, PFFS plans reimbursed Medicare providers based on procedure codes (not diagnoses) at standard Medicare rates. Thus, PFFS plans had access to only a subset of the tools available to managed care plans to influence diagnoses recorded within the physician’s practice. In particular, PFFS insurers could not arrange a contract with providers that directly financially rewarded intensive coding. PFFS plans could, nonetheless, set lower copays for routine and specialist visits than beneficiaries faced under FFS, which may have increased contact with providers. PFFS plans could also utilize home visits and perform chart reviews.

Table 4:

Heterogeneity by Plan Type and by Plan Integration

| Heterogeneity by Plan Type |

By Plan Ownership |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| HMO & PPO Share, t-1 | 0.089** (0.026) |

0.088** (0.026) |

|||

| HMO Share, t-1 | 0.103** (0.028) |

0.101** (0.028) |

|||

| PPO Share, t-1 | 0.068* (0.028) |

0.068* (0.028) |

|||

| PFFS Share, t-1 | 0.057* (0.025) |

0.058* (0.025) |

0.057* (0.025) |

0.058* (0.025) |

|

| Employer MA Share, t-1 | 0.041** (0.012) |

0.041** (0.012) |

0.041** (0.012) |

0.041** (0.012) |

|

| Non-Provider-Owned Plans Share, t-1 | 0.061** (0.011) |

||||

| Provider-Owned Plans Share, t-1 | 0.156** (0.031) |

||||

| Main Effects | |||||

| County FE | X | X | X | X | X |

| Year FE | X | X | X | X | X |

| Additional Controls | |||||

| State X Year Trend | X | X | X | X | X |

| County X Year Demographics | X | X | X | X | X |

| Special Need Plans (SNP) Share | X | X | |||

| Observations | 15,640 | 15,640 | 15,640 | 15,640 | 15,640 |

Note: The table shows coefficients from difference-in-differences regressions in which the dependent variable is the average risk score in the market (county). Effects of lagged (t − 1) MA penetration are displayed, disaggregated in columns 1 through 4 by shares of the Medicare market in each category of MA plans (HMO/PPO/PFFS/Employer MA). Share variables are fractions of the full (MA plus FFS) Medicare population. Regressions in these columns additionally control for the corresponding contemporaneous (t) effects and the share and lagged share of all other contract types. In column 5, MA penetration is disaggregated by whether plans were provider-owned, following the definitions constructed by Frakt, Pizer and Feldman (2013) (see Section A.10 for full details). Observations are county × years. Controls are as described in Table 2. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the county level.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

As in the main analysis, the coefficients of interest in Table 4 are on lagged penetration.26 Point estimates in the table show that the strongest coding intensity is associated with managed care plans generally, and HMOs in particular. Risk scores in HMO plans are around 10% higher than they would have been for the same Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in FFS. PPO coding intensity is around 7% higher than FFS. PFFS and employer MA plans, while intensely coded relative to FFS, exhibit relatively smaller effects. Because today, PFFS comprises a very small (<1%) fraction of MA enrollment, estimates of upcoding based on changes in the HMO/PPO shares (row 1 of columns 1 and 2) are likely to be more informative of typical MA coding intensity differences today. Estimates inclusive of PFFS (as in Table 2) are informative of the overall budgetary impact of MA during our study period.

In the last column of Table 4, we report on a complementary analysis that classifies MA plans according to whether the plan was provider-owned, using data collected by Frakt, Pizer and Feldman (2013). We describe these data in Appendix Section A.10. The coefficients show that provider ownership is associated with risk scores that are about 16% higher than in FFS Medicare, while the average among all other MA plans is a 6% coding difference. This evidence suggests that the costs of aligning physician and insurer incentives may decline significantly with vertical integration and that vertical integration may facilitate gaming of the regulatory system.27 In Appendix Tables A6 through A8 we investigate heterogeneity across other plan characteristics (e.g. for-profit/not-for-profit) and county characteristics (e.g. use of electronic health records, market concentration, population size, etc.) but do not find any other consistent patterns.

7. Individual-Level Evidence

We next turn to a smaller, individual-level dataset. In these data, we can exploit the within-person change in insurance status that occurs when 64-year-olds age into Medicare at 65 and choose either FFS or MA. This allows us to demonstrate the robustness of our key empirical results to an entirely different identification strategy and to investigate the margins along which upcoding occurs.28

7.1. Data: Massachusetts All-Payer Claims

We use the 2010–2013 Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Dataset (APCD) to track how reported diagnoses for a person change when the person enrolls in MA. The APCD includes an individual identifier that allows us to follow consumers across years and health plans as they change insurance status. These data cover all private insurer claims data, including Medicare Advantage, Medigap, employer, and individual-market commercial insurers. Therefore, we can observe a consumer in her employer plan at age 64 and then again in her private MA plan or in FFS with Medigap at age 65.29

We focus on two groups of consumers in the data: all individuals who join an MA plan within one year of their 65th birthday and all individuals who join FFS with a Medigap plan within one year of their 65th birthday. We divide enrollment spells into 6-month blocks relative to the start of enrollment and limit the sample to individuals with at least six months of data before and after joining MA or Medigap. These 6-month periods include different calendar months × years for different individuals. For example, for an individual who enrolled in Medicare in March 2010, period −1 is September 2009 through February 2010, period 0 is March 2010 through August 2010, period 1 is September 2010 through February 2011, and so on. For the pre-Medicare period we include all 6-month periods during which the individual was continuously enrolled in some form of health insurance. For the post-Medicare period, we include all 6-month periods during which the individual was continuously enrolled in either MA or Medigap. Our final sample includes 34,901 Medigap enrollees and 10,337 MA enrollees. The mean number of 6-month periods prior to Medicare enrollment that we observe is 4.6 (just over 2 years), and the mean number of 6-month periods after Medicare enrollment is 4.4. Additional details regarding the sample construction are included in Appendix Section A.13.

We use diagnoses from the claims data to generate risk scores for each individual based on diagnosed conditions during each 6-month period in the individual’s enrollment panel. Risk scores are calculated according to the same Medicare Advantage HCC model regardless of the plan type in which the consumer is enrolled (i.e., employer, individual market, FFS, or MA). These risk scores do not share the lagged property of the scores from the administrative data used in Sections 5 and 6 as we calculate the scores ourselves based on current-year diagnoses. We normalize these partial-year risk scores by dividing by the pre-Medicare enrollment mean of the 6-month risk score.

7.2. Risk Scores across the Age 65 Threshold

To recover the effect of entering MA relative to entering FFS on an individual’s risk score, we estimate the following difference-in-differences regression:

| (7) |

where rimt represents i’s risk score during 6-month period t, MAi is an indicator equal to one for anyone in MA or who will eventually elect to join MA, Postt is an indicator equal to one for periods of post-Medicare enrollment, αt represents fixed effects for each 6-month period relative to initial Medicare enrollment, and Γm controls for a full set of month × year of Medicare entry fixed effects (e.g., joined Medicare in June 2012). β2 is the difference-in-differences coefficient of interest. It measures the differential change in risk scores between the pre- and post-Medicare periods for individuals enrolling in MA vs. individuals enrolling in FFS. We also estimate versions of this regression where we include individual fixed effects or match individuals on pre-enrollment characteristics.

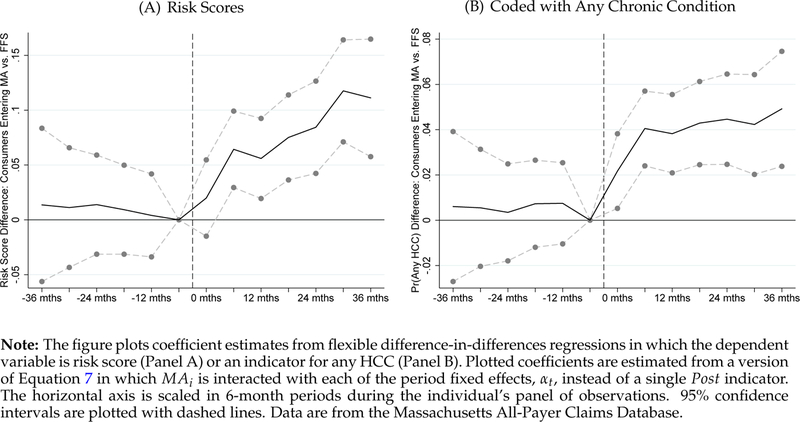

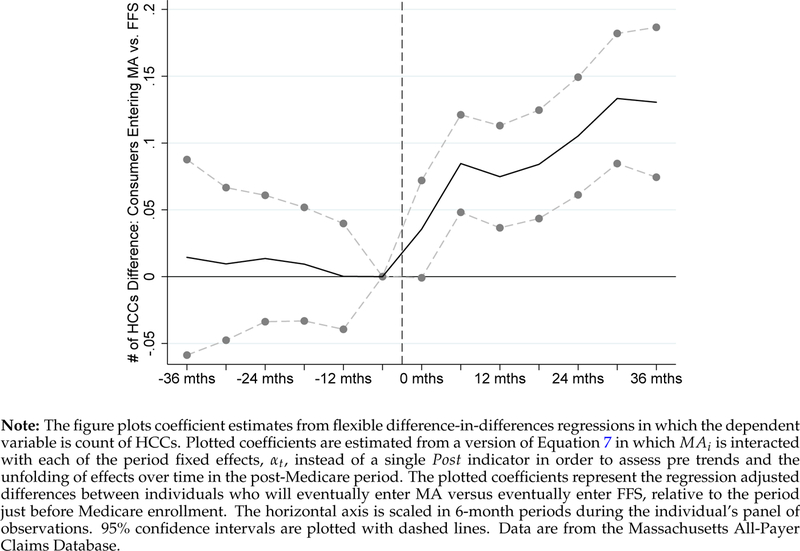

We begin in Figure 3A by plotting the coefficients from an event study version of Equation (7) where we interact MAi with each of the period fixed effects (αt) instead of a single Post indicator. This specification makes it simple to assess the existence of differential pre-trends, which here would indicate that people who would eventually choose MA were already on a path to higher risk scores prior to their actual Medicare enrollment. Each plotted coefficient represents the difference in the differences of risk scores of people entering MA vs. FFS in the indicated period relative to the period just before Medicare enrollment (period −1). The dashed vertical line indicates Medicare enrollment (the start of period 0). The figure shows that during the 36 months prior to Medicare enrollment, the risk scores for the MA and FFS groups were not differentially trending. Post-Medicare enrollment, however, there is a clear divergence, with risk scores for the MA group increasing much more rapidly than risk scores for the FFS group. By the sixth 6-month period (3 years after Medicare enrollment), normalized risk scores for the MA group were higher by a little more than 10% of the pre-period mean, relative to the FFS group. The apparent growth in the MA coding effect from time zero to 36 months is consistent with the ratcheting-up interpretation of results from column 4 of Table 2 (in the national sample and main identification strategy). These showed that effects were larger (8.7%) by the second year following a shift in θ. Figures 3B and A5 present similar event studies where the dependent variable is the probability of having any HCC during the 6-month period and the number of HCCs, respectively. These figures show similar patterns.

Figure 3:

Alternative Identification: Diff-in-Diff Event Study at Age 65, MA versus FFS

Table 5 presents regression estimates in which all 6-month periods are grouped as either pre- or post-Medicare enrollment spells, as in Equation (7). Column 1 presents results without individual fixed effects, while column 2 includes individual fixed effects, which subsume the MA indicator. The negative coefficient on MAi in the first row of column 1 indicates that during the pre-Medicare periods, people who would eventually select into MA had lower risk scores than people who would eventually select FFS, consistent with previous evidence that MA is advantageously selected (e.g., Curto et al., 2014). The coefficients of interest on MAi × Postt indicate that risk scores for the MA group grew more rapidly in the post-Medicare periods relative to the FFS group: The risk score of an individual enrolling in MA increased by 4.7 to 5.8% more than the risk score of an individual enrolling in FFS between the pre- and post-Medicare periods. This magnitude is consistent with the visual evidence in Figure 3, if one took the mean over the entire post period.

Table 5:

Alternative Identification: Coding Differences at Age 65 Threshold, MA vs. FFS

| Dependent Variable: Specification: Sample Restriction: |

Risk Score |

At least 1HCC |

Count of HCCs |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-in-D Full Sample |

Matching D-in-D Full Sample |

Extensive Margin Full Sample |

Intensive Margin At least 1 HCC |

|||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| Selected MA | −0.113** (0.007) |

−0.116** (0.006) |

−0.054** (0.005) |

−0.038** (0.005) |

−0.028** (0.005) |

−0.043** (0.003) |

−0.143** (0.014) |

|||

| Post-65 X Selected MA | 0.058** (0.009) |

0.047** (0.007) |

0.058** (0.007) |

0.054** (0.007) |

0.060** (0.007) |

0.051** (0.007) |

0.033** (0.004) |

0.033** (0.003) |

0.090** (0.018) |

0.071** (0.018) |

| Person FE | X | X | X | |||||||

| Matching Variables: | ||||||||||

| Gender/County | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Count of HCCs | X | X | ||||||||

| Risk Score | X | X | ||||||||

| Mean of Dep. Var. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

| Observations | 319,094 | 319,094 | 316,861 | 314,293 | 288,407 | 287,676 | 319,094 | 319,094 | 118,327 | 118,327 |

Note: The table shows coefficients from difference-in-differences regressions described by Eq. 7 in which the dependent variables are the risk score (columns 1 through 6), an indicator for having at least one chronic condition (HCC) during the period (columns 7 and 8), and the count of chronic conditions, conditional on periods in which individuals have at least one HCC (columns 9 and 10). All regressions compare coding outcomes pre- and post-Medicare enrollment among individuals who select MA relative to individuals who select FFS. Data are from the Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Dataset. The unit of observation is the person-by-six month period, where six-month periods are defined relative to the month in which the individual joined Medicare. Columns 3–6 report coefficients from regressions where the observations are weighted with propensity scores estimated using the indicated matching variables. The coefficient on “Selected MA” should be interpreted as the pre-Medicare enrollment difference in the outcome for individuals who will eventually enroll in an MA plan versus individuals who will eventually enroll in FFS. The coefficient on “Post-65 X Selected MA” is the difference-in-differences coefficient. Standard errors in parentheses are clustered at the person level.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

The results are robust to alternative ways of controlling for MA/FFS selection. In columns 3 through 6 of Table 5, we estimate versions of the regression in column 1 in which we match individuals on pre-period observable characteristics: gender, county of residence, pre-Medicare risk scores, and pre-Medicare count of HCCs. For these regressions, we generate propensity scores on combinations of these variables, then weight the difference-in-differences regressions using these scores, dropping observations for which there is no common support. This matching procedure significantly reduces the coefficient that reflects selection: the coefficient on MAi reduces from −0.112 to −0.028. But even as the selection estimate is reduced, estimates of the difference-in-differences effect of interest (the effect of MA enrollment on risk scores in the post period) are stable, remaining similar in size to the main specifications in columns 1 and 2. In Appendix Table A9, we estimate versions of Equation (7) that include interactions between Postt and a full set of fixed effects for an individual’s pre-Medicare plan. Effects are identified off of consumers in the same pre-65 employer or individual market plan who make a different MA/FFS choice at 65. In all robustness exercises, the results are consistent with columns 1 though 6 of Table 5. Overall, these individual-level results support and complement the findings of our main analysis.

7.3. Mechanisms

In addition to the estimates of the coding effects, the richer data in the APCD allows us to investigate some of the mechanisms behind the differential coding increases we observe in MA. Of particular interest is who is upcoded: relatively healthy or relatively sick enrollees? Enrollees who, if not for MA, would not have made contact with the medical system in a given period, or enrollees with regular healthcare utilization regardless of the MA/FFS enrollment choice? Understanding such questions is useful in forming future regulatory frameworks that are less susceptible to manipulable diagnosis coding.

In columns 7 through 10 of Table 5, we investigate MA coding effects along the extensive and intensive margins. In columns 7 and 8, we replace the dependent variable with an indicator for having at least one HCC in a 6-month period. Individuals in the MA group have a lower probability of having any HCC during the pre-Medicare period, but their probability of having any HCC increases more in the post-Medicare periods relative to the FFS group. Columns 9 and 10 investigate the intensive margin. The dependent variable in these columns is the number of HCCs during the 6-month period, restricted to person-period observations with at least one HCC. We find large effects, indicating that the MA coding effect occurs on both the extensive and intensive margins.

In Appendix Table A10, we variously restrict the sample to different subsets based on pre-Medicare health status, as reflected by the diagnosed chronic conditions in the pre-Medicare employer plan. These results show that there are important effects of MA on diagnosis coding for both the healthy and the sick and that the coding effects for the sick are larger.