During the past 4 months, we have witnessed unfolding of the COVID-19 pandemic that by now has affected every corner of the planet, infecting more than 3.3 million people, killing more than 234,000,[1,2] and directly or indirectly affecting billions of individuals.[3] The quick rise in both cases and deaths was due to the high infectivity of the virus, quickly overwhelming health-care systems and prompting physical distancing measures of historically unprecedented scale.[4] The speed and robustness of public health responses within individual countries appear to be associated with early successful containment, fewer cases, and lower mortality.[5,6] Driven by fears just as powerful as hopes, the humanity is now firmly united in defeating the common enemy, severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

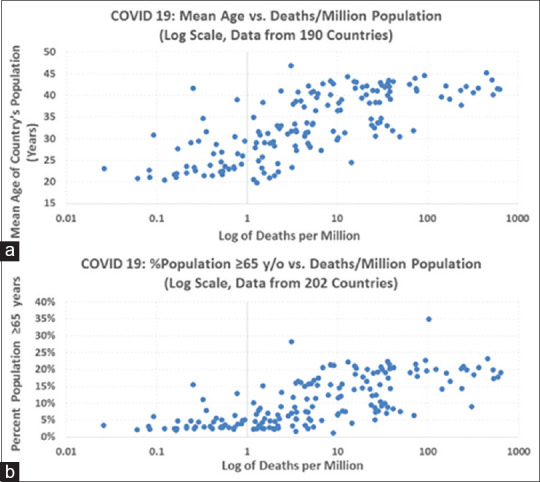

As country after country fell victim to the relentless disease, disbelief gave way to horror as the “far-away problem” became one that hits all too close to home.[7] One new fact after another emerged about our new mortal enemy – from its ruthless affinity for those with comorbid conditions to the high proportion of asymptomatic or presymptomatic transmission.[4] With few exceptions, there is a striking yet expected relationship between the average recorded daily deaths per million population and both the average age and the percentage of geriatric population among countries around the world [Figure 1a and b][8,9,10]. There may also be a similar correlation between the number of symptomatic cases and the average population age,[11] suggesting strongly that SARS-CoV-2 does not appear to discriminate by national wealth, per-capita income, or number of hospital beds per person.[11,12,13,14] It is hoped that the costly lessons of what is believed to be only the first global wave of COVID-19 will help inform any subsequent waves of COVID-19 disease, as well as future pandemic response across both high-income countries (HICs) and low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs).[14,15]

Figure 1.

Deaths per million population versus (a, top) mean age of country's population and percentage of country's population ≥65 years (b, bottom)

The collective learning among geographically separated members of the international medical community is another example of the new global age of instant scientific communication and synergy creation. In this context, several group experiences helped change and refine how we treat patients. For example, the initial management approach in Europe and America was to intubate early, when the COVID-19 respiratory failure was still mild.[16,17,18] However, this approach did not seem to reduce mortality in the affluent Lombardy region of Italy, where some of the highest mortality rates in the world were recorded.[16] This aggressive intubation approach was contrasted to a study from China where patients with COVID-19 pneumonia were treated with high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) as the first-line therapy, followed by a stepwise escalation to noninvasive ventilation (NIV) and then tracheal intubation for refractory cases.[19] In the latter experience, only 4 out of 318 patients were eventually intubated.[19] Similar experiences and success stories have been reported with early proning of nonintubated patients.[4,20]

Recent reports also suggest that many patients with COVID-19 present with so-called “silent hypoxia” that is characterized by the apparent absence of dyspnea or overt air hunger.[21,22] Of interest, patients with such “silent hypoxia” appear to be more likely to progress on to develop severe respiratory failure of COVID-19 within 2–4 days without early aggressive intervention (e.g., HFNC and nonintubated proning). Mechanistically, the damaged lungs have impaired O2 handling, but the CO2 exchange is still intact. Because CO2 is the main driver for dyspnea, patients may feel falsely reassured and thus do not seek emergent medical attention. Instead, hypoxia is compensated by involuntary tachypnea for 2–4 days while the lung injury progresses, up until a cytokine storm occurs, with ensuing dyspnea, elevated CO2, and the rapid development of severe respiratory failure.[21,22] From public health perspective, this phenomenon requires early and aggressive implementation of home- or community-based pulse oximetry programs, combined with around-the-clock telemedicine services, to effectively intercept patients who may be entering the rapid deterioration phase of COVID-19.[21,23,24,25]

To help address the impact of “silent hypoxia” in both LMIC and HIC settings, we recommend the following combined public/community health plus hospital based-management approach to decrease the need for invasive ventilation and overall mortality in the event of widespread community transmission:

Approximately 90% of COVID-19 patients do not require hospitalization, and it may be sufficient to isolate mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic cases in their homes for 14–28 days[26]

When continuous pulse oximetry is not available, monitor those showing mild symptoms at least every 8–12 h for “silent hypoxia” – also see ACAIM-WACEM Joint Working Group clinical management algorithm[22]

Public education and increased access to pulse oximetry near-patient homes will be critical to successful remediation of the “silent hypoxia” phenomenon

-

Once detected, treatment of silent hypoxia (SpO2< 90%–93% or respiratory rate >25/min) should be started according to the following stepwise escalation protocol:[22,27]

- Oxygen through nasal prongs or face mask 5–6 L/min

- If SpO2 remains <88% on nasal prongs, use nonrebreathing masks 10–15 L/min

- If SpO2 remains <88% on non-rebreathing masks, use either NIV or HFNC (depending on availability)

- If SpO2 remains <88% on NIV or HFNC, consider invasive ventilation.

Keep patient in prone position alternating with sitting position for >16 h/day or as long as reasonably feasible[4,28]

Consider restricted use of intravenous fluids and the use of corticosteroids for severe respiratory failure as per recommendations,[17] with appropriate medication including low molecular weight heparin and end-organ support as per prevailing recommendations.

As various hospital and intensive care therapies and management approaches take shape, so does an entire new universe of telemedicine as it comes of age. Following its inception, telehealth was viewed by some as a “modality looking for indications.”[29,30] This is no longer the case, as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently adopted equivalency for tele- and in-person care, voiding the need for the existence of a prior patient–physician relationship to pay claims for telemedicine visits.[31] This is just one way in which the COVID-19 pandemic permanently changed the health-care landscape, with true effects and the magnitude of such tectonic shift to be felt for years to come.[25] In addition to enabling ongoing care of patients with chronic medical conditions, the new paradigm also enables innovative approaches to cross-border specialty expertise sharing as well as continued productive employment of health-care providers who may be under quarantine orders.[4,25] The current pandemic is likely the beginning of a long-term trend toward sustainable, home-based care models.[30,32]

As frontline medical personnel make important clinical discoveries and advances, so do basic and translational scientists. Despite multiple clinical studies, from retrospective reviews to prospective randomized trials, showing limited or no efficacy of one therapeutic agent after another, much hope remains as the resilient cycle of scientific discovery ploughs ahead.[4,33,34,35] And although there is no “magic bullet” in sight, several important discoveries were made in the areas of antivirals (preliminary results suggesting that remdesivir may shorten the duration of illness) and vaccines.[36,37,38,39] The first, and somewhat surprising finding, is the association between universal Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) national vaccination policies and reduced morbidity and mortality among COVID-19 patients.[37] Clinical trials of BCG vaccination among health-care workers are ongoing.[40,41,42] The second, and somewhat expected finding, is the apparent efficacy of convalescent plasma in the management of severe COVID-19 infections.[43,44,45] A longer-term, sustainable derivative that builds on the theme of convalescent plasma is the identification and synthesis of highly effective anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.[35,46,47,48] Finally, important new developments are emerging in the race to produce an effective human vaccine,[38,49,50] although the final product will likely not be available in the immediate future.

In addition to the development of new therapeutics and vaccines, there is a tremendous need for better understanding of the COVID-19 clinical disease. For example, we do not fully understand why the disease seems to take a largely binary course – for some, it appears to be a “flu-like illness,” while for others, it takes a much more acute course. The differentiation between the two “disease paths” seems to be occurring right around the 2nd week of the illness.[51] Still, etiologic factors responsible for this phenomenon remain unknown. In another highly controversial observation, tobacco smokers appeared to be somewhat protected from the more severe manifestations of COVID-19, but it is not clear what factors (or unrecognized biases) may be responsible for these preliminary findings and confirmatory research will be required to substantiate any associated claims.[52,53] The ongoing recognition of new signs and symptoms, long after the first reported case of COVID-19, exemplifies the diverse number of presentations associated with the viral illness. For example, only recently was the phenomenon of “COVID toes” described,[54] and there is a growing recognition of the association between COVID-19 and thromboembolic phenomena.[55,56] There is also the spirit of innovation in the face of adversity. For example, when faced with acute shortage of N95 respirator masks and face shields, citizenry around the globe began designing, testing, and making their own substitute do-it-yourself products, with various degrees of success and air filtration effectiveness.[57,58,59]

As the global fight against the pandemic continues, we must remember and persist in the hope that this traumatic event will eventually come to an end. With this optimistic outlook, we must start thinking about the humanity's emergence from the state of “deep freeze,” physical distancing, and the respectful fear of the unknown. Key to this post-COVID-19 “rebirth” of sorts will be a well-organized, well-thought-out system of checks and balances that will allow the maintenance of appropriate safety measures while also permitting the return of economic activity in the broadest possible sense. A formidable new challenge will be the copresence of COVID-19 and influenza during the next annual “flu season,” effectively resulting in what the authors are coining as “Covi-Flu season.” The costs of dual testing, personal protective equipment, as well as the need for high degree of clinical vigilance are likely to create significant inefficiencies across our clinics and emergency departments. To overcome this and many other challenges, some degree of “collective sacrifice” will likely be necessary, whether it means large-scale testing and issuing vaccination/immunity certificates, or perhaps a protracted period of continued social distancing with associated ramification of being “together but separated.” Ultimately, these difficult questions will need to be answered by citizens of each region of the globe while maintaining the utmost respect for the prevailing cultural norms, individual freedoms, and the collective societal well-being. We live in special times, and we shall emerge from the great challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic together, as a one human family, stronger, wiser, and better.

REFERENCES

- 1.World-O-Meter. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 29]. Available from: https://wwwworldometersinfo/coronavirus/

- 2.World Health Organization. Rolling Updates on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) World Health Organization; 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 27]. Available from: https://wwwwhoint/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gozes O, Frid-Adar M, Greenspan H, Browning PD, Zhang H, Ji W. Rapid ai Development Cycle for the Coronavirus (covid-19) Pandemic: Initial Results for Automated Detection and Patient Monitoring Using Deep Learning ct Image. Analysis arXiv preprint arXiv; 200305037. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stawicki SP, Jeanmonod R, Miller AC, Paladino L, Gaieski DF, Yaffee AQ, et al. The 2019-2020 Novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) pandemic: A joint american college of academic international medicine-world academic council of emergency medicine multidisciplinary COVID-19 working group statement. J Global Infect Dis. 2020;12:47–93. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_86_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Day M. Eastern European Economies Begin to Reopen: Former Eastern Block Nations Appear to have Coped Much Better with the Pandemic than those in Western Europe. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://wwwtelegraphcouk/news/2020/04/30/eastern-european- economies-begin-reopen/

- 6.Giugliano F. Greece Shows how to Handle the Crisis: The Government Imposed Severe Social Distancing Measures Much Earlier than Others. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://wwwbloombergcom/opinion/articles/2020-04-10/greece- handled-coronavirus-crisis-better-than-italy-and-spain .

- 7.Buchan G. Australia Goes Hard and Goes Early on Covid-19. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://wwwcsisorg/analysis/australia-goes-hard-and-goes-early-covid-19 .

- 8.Department of Economic and Social Affairs, P.D. United Nations, World Population Prospects; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Max Roser HR, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) Published online at OurWorldInDataorg. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agency CI. The World Factbook 2020. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports. World Health Organization; 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 07]. Available from: https://wwwwhoint/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports . [Google Scholar]

- 12.The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://datahelpdeskworldbankorg/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups .

- 13.World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory Data Repository: Hospital Bed Density Data by Country. World Health Organization; 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://appswhoint/gho/data/viewmainHS07v . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harden RD, Ivers LC. Anticipating the Next Waves of COVID-19. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://thehillcom/opinion/healthcare/490028-anticipating-the-next-waves-of-covid-19 .

- 15.Lawton G. Will the Spread of Covid-19 be Affected by Changing Seasons. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://wwwnewscientistcom/article/2239380-will-the-spread-of-covid-19-be-affected-by-changing- seasons/

- 16.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Massimo Antonelli M, Cabrini L, et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region Italy. Jama. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poston JT, Patel BK, Davis AM. Management of Critically Ill Adults with COVID-19. Jama. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phua J, Weng L, Ling L, Egi M, Lim CM, Divatia JV, et al. Asian Critical Care Clinical Trials Group. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:506–17. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang K, Zhao W, Li J, Shu W, Duan J. The experience of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus -infected pneumonia in two hospitals of Chongqing, China. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00653-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siow WT, et al. Managing COVID-19 in resource-limited settings: Critical care considerations. Bio Med Cent Crit Care. 2020;24:167. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02890-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levitan R. The infection that's silently killing coronavirus patients. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://wwwnytimescom/2020/04/20/opinion/sunday/coronavirus-testing-pneumoniahtml .

- 22.Galwankar S, Paladino L, Gaieski DF, Nanayakkara P, DiSomma S, Grover J, et al. Management algorithm for subclinical hypoxemia in COVID-19 patients: Intercepting the 'silent killer. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2020:13. doi: 10.4103/JETS.JETS_72_20. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nacoti M, et al. At the epicenter of the Covid-19 pandemic and humanitarian crises in Italy: Changing perspectives on preparation and mitigation. NEJM Catalyst Innovat Care Delivery. 2020:1. Catal Non-Issue Content [Internet] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong AW, et al. Practical considerations for the diagnosis and treatment of fibrotic interstitial lung disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chest. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.019. S0012-3692(20)30756-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chauhan V, et al. Novel coronavirus (COVID-19): Leveraging telemedicine to optimize care while minimizing exposures and viral transmission. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2020;13:20. doi: 10.4103/JETS.JETS_32_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burrer SL, et al. Characteristics of Health Care Personnel with COVID-19-United States, February 12–April 9, 2020. 2020 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dondorp AM, et al. Respiratory support in novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) patients, with a focus on resource-limited settings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020 doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0283. 104269/ajtmh20-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun Q, Qiu H, Huang M, Yang Y. Lower mortality of COVID-19 by early recognition and intervention: experience from Jiangsu Province. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00650-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John O, Jha V. Karger Publishers; 2019. Remote Patient Management in Peritoneal Dialysis: An Answer to an Unmet Clinical Need, in Remote Patient Management in Peritoneal Dialysis; pp. 99–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wade VA, Taylor AD, Kidd MR, Carati C. Transitioning a home telehealth project into a sustainable, large-scale service: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:183. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1436-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bini SA, Schilling PL, Patel SP, Kalore NV, Ast M, Maratt J. Digital orthopaedics A glimpse into the future in the midst of a pandemic. J Arthrop. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamsu-Foguem B, Foguem C. Telemedicine and mobile health with integrative medicine in developing countries. Health Policy Technol. 2014;3:264–71. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sayburn A. Covid-19: trials of four potential treatments to generate “robust data” of what works. BMJ. 2020 Mar 24;368:m1206. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freund A. Coronavirus Studies: Chloroquine is Ineffective and Dangerous. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://wwwdwcom/en/chloroquine-is-ineffective-and-dangerous/a-53188219 .

- 35.Dhama K, Sharun K, Tiwari R, Dadar M, Malik YS, Singh KP. COVID-19, an emerging coronavirus infection: Advances and prospects in designing and developing vaccines, immunotherapeutics, and therapeutics [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 18] Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1735227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krawczy K. FDA Reportedly Plans to Authorize Emergency use of Largely Untested Drug to Treat Coronavirus. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://newsyahoocom/fda-reportedly-plans-authorize-emergency-190500694html .

- 37.Miller A, Reandelar MJ, Fasciglione K, Roumenova V, Li Y, Otazu GH. Correlation between universal BCG vaccination policy and reduced morbidity and mortality for COVID-19: An epidemiological study. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prompetchara E, Ketloy C, Palaga T. Immune responses in COVID-19 and potential vaccines: Lessons learned from SARS and MERS epidemic. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2020;38:1–9. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed SF, Quadeer AA, McKay MR. Preliminary identification of potential vaccine targets for the COVID-19 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on SARS-CoV immunological studies. Viruses. 2020;12:254. doi: 10.3390/v12030254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.ClinicalTrials. Gov BCG Vaccination to Protect Healthcare Workers Against COVID-19 (BRACE) 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 05]. Available from: https://clinicaltrialsgov/ct2/show/NCT04327206 .

- 41.Prestigiacomo A. Vaccine From 1920s Being Tested To Fight Coronavirus. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 05]. Available from: https://wwwdailywirecom/news/vaccine-from-1920s-being-tested-to-fight-coronavirus .

- 42.Mack E. A Vaccine from the 1920s is Now Being Tested for use Against the Coronavirus Pandemic. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: https://wwwforbescom/sites/ericmack/2020/03/31/a-vaccine-from-the-1920s-could-help-fight-the-coronavirus-pandemic/#17a40c3c1220 .

- 43.Shen C, Wang Z, Zhao F, Yang Y, Li J, Yuan J. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. Jama. 2020;323:1582–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duan K, Liu B, Li C, Zhang H, Yu T, Qu J. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proceed Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:9490–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004168117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanne JH. Covid-19: FDA approves use of convalescent plasma to treat critically ill patients. BMJ. 2020;368:m1256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1256. Published 2020 Mar 26. doi:10.1136/bmj. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shanmugaraj B, Siriwattananon K, Wangkanont K, Phoolcharoen W. Perspectives on monoclonal antibody therapy as potential therapeutic intervention for Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2020;38:10–18. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0773. doi:10.12932/AP-200220-0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu C, Zhou Q, Li Y, Garner L V, Watkins SP, Carter LJ, Smoot J, et al. Research and Development on Therapeutic Agents and Vaccines for COVID-19 and Related Human Coronavirus Diseases. ACS central science. 2020;6:315–31. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li X, Geng M, Peng Y, Meng L, Lu S. Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 5] J Pharm Anal. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thanh Le T, Andreadakis Z, Kumar A, Gómez Román R, Tollefsen S, Saville M, et al. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2020;19(5):305–306. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen WH, Strych U, Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME. The SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Pipeline: an Overview [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 3] Curr Trop Med Rep. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s40475-020-00201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernstein L, Cha AE. Second-Week Crash' is time of Peril for Some Covid-19 Patients. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://wwwwashingtonpostcom/health/second-week-crash-is-time-of-peril-for-some-covid-19- patients/2020/04/29/3940fee2-8970-11ea-8ac1-bfb250876b7a_storyhtml .

- 52.O'Donnell T. Scientists are Perplexed by the Low Rate of Coronavirus Hospitalizations. Among Smokers Nicotine May Hold the Answer. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://theweekcom/speedreads/911429/scientists-are-perplexed-by-low-rate-coronavirus-hospitalizations- among-smokers-nicotine-may-hold-answer .

- 53.Farsalinos K, Barbouni A, Niaura R. Smoking, Vaping and Hospitalization for COVID-19. Qeios. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee JY. 'COVID toes' Might be the Latest Unusual Sign that People are Infected with the Novel Coronavirus. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://wwwbusinessinsidercom/covid-toes-frostbite-coronavirus-skin-lesion-discolored-swollen-feet- 2020-4 .

- 55.Connors JM, Levy JH. Thromboinflammation and the hypercoagulability of COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 17] J Thromb Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14849. 101111/jth14849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hamilton J. Doctors Link COVID-19 To Potentially Deadly Blood Clots and Strokes. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://wwwnprorg/sections/health-shots/2020/04/29/847917017/doctors-link-covid-19-to-potentially-deadly-blood-clots-and- strokes .

- 57.Berkowitz B, Steckelberg A. Answers to your DIY Face Mask Questions, Including what Material you Should Use. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://wwwwashingtonpostcom/health/2020/04/07/answers-your-diy-face-mask-questions-including-what- material-you-should-use/arc404=true .

- 58.Konda A, Prakash A, Moss GA, Schmoldt M, Grant GD, Guha S. Aerosol Filtration Efficiency of Common Fabrics Used in Respiratory. Cloth Masks ACS Nano. 2020 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toussaint K. Makers are Rushing to Fight Coronavirus with 3D Printed face Shields and Test Swabs. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 30]. Available from: https://wwwfastcompanycom/90482710/makers-are-rushing-to-fight-coronavirus-with-3d- printed-face-shields-and-test-swabs .