Abstract

Human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) is an emerging life-threatening tick-borne disease caused by the obligate intracellular bacterium Ehrlichia chaffeensis. HME is often presented as a nonspecific flu-like illness characterized by presence of fever, headache, malaise, and myalgia. However, in some cases the disease can evolve to a severe form, which is commonly marked by acute liver injury followed by multi-organ failure and toxic shock-like syndrome [1–3]. Macrophages and monocytes are the major target cells for Ehrlichia, although this bacterium can infect other cell types such as hepatocytes and endothelial cells [4]. In this article, we discuss how macrophages polarization to M1 or M2 phenotypes dictate the severity of ehrlichiosis and the outcome of infection. We will also discuss the potential mechanisms that regulate such polarization.

Keywords: Ehrlichiosis, Intracellular Pathogens, Tick-borne diseases, Immunopathology, Liver injury, mTORC1, Macrophages

M1-M2 Macrophages Polarization

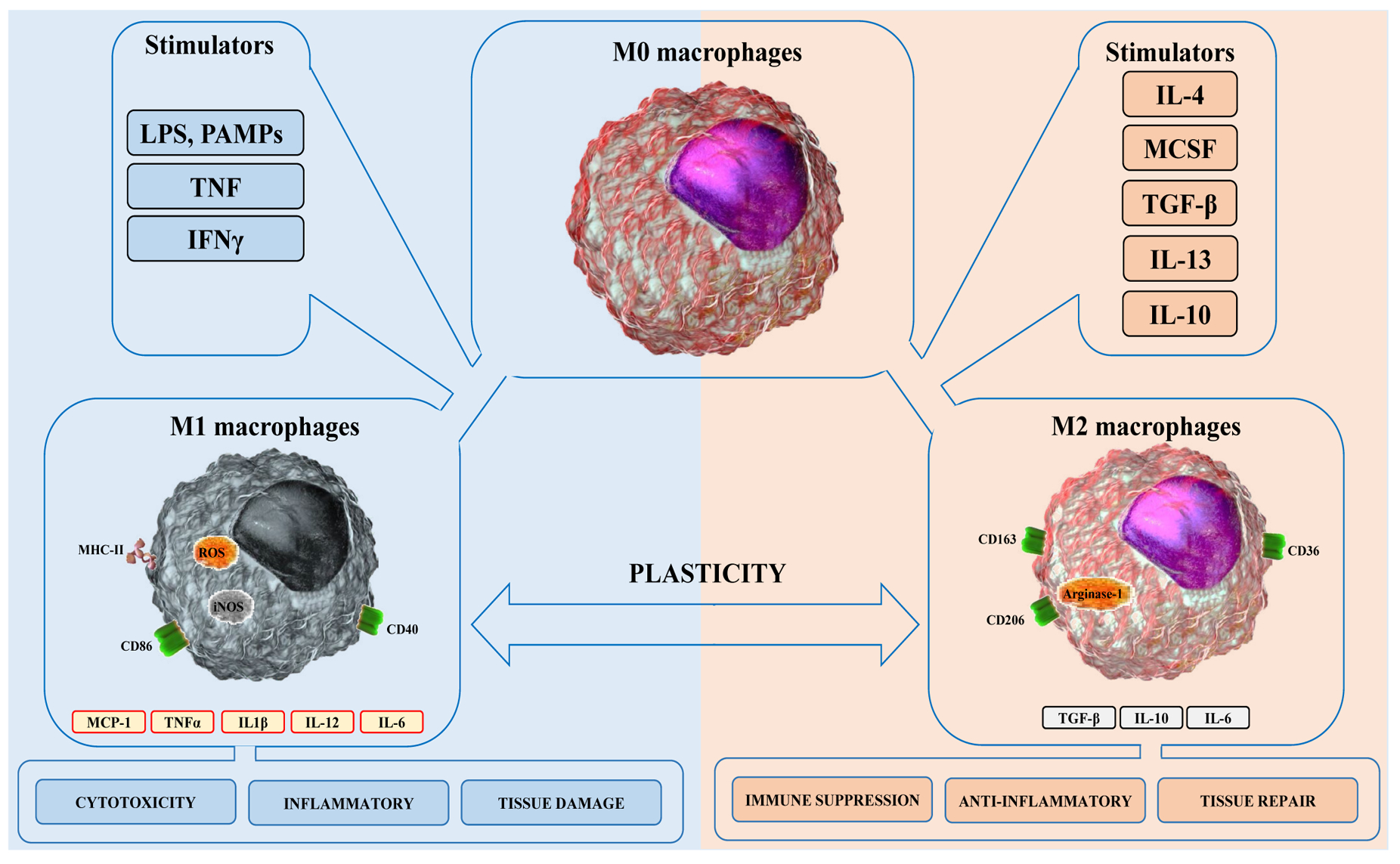

Macrophages are innate immune cells that play a key role in regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses against infections with several pathogens as they respond to pathogens and tissue injury, serve as antigen presenting cells priming the adaptive immune response, drive inflammation and host defense as well as repairing damaged tissue [5–7]. Macrophages reside in almost all of the lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues [8]. Two major lineages are currently known: cells that are derived from myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow (BM) that give rise to blood-circulating monocytes that migrate to sites of host insult, and macrophages that are derived from the yolk sac and present in the tissues as resident macrophages [9–11]. Examples of tissue-resident macrophages are alveolar macrophages in the lung and Kupffer cells in the liver. Several macrophage subsets with distinct functions have been described. Classically activated macrophages (M1 macrophages) mediates host defense against several bacterial, viral and protozoal pathogens and they play a role in antitumor immunity [12,13]. These M1 cells are characterized by MHC class II, CD86 and CD40 upregulation [14,15], downregulation of mannose receptor (CD206), their ability to engulf and digest microbes, secrete Pro-inflammatory/T helper 1 (Th1)-promoting cytokines such as IL-12, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α production of microbicidal molecules; nitric oxide (NO), and reactive oxygen species (ROS), secretion of chemokines for recruitment of immune cells such as CCL2/MCP-1, and present antigens to T cells for the initiation of adaptive immunity [16–19]. Alternatively activated macrophages (M2 macrophages), on the other hand, are characterized by upregulation of markers such as CD206, arginase-1, IL-10, and TGF-β [20,21] (Figure 1). M2 cells play a role in down regulating the inflammatory mediators, up regulating the anti- inflammatory mediators, expressing scavenging receptors (e.g. mannose receptor), phagocytizing apoptotic bodies and cellular debris, and promoting wound healing and tissue repair [17]. These M2 macrophages are a strong inducer of T helper 2 (Th2) cells and/or regulatory T cells. M1-macrophage polarization is enhanced by both IFN-γ and Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), while M2 polarization promoted via IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 [22,23].

Figure 1: M1 and M2 macrophages polarization.

Macrophages are differentiated into M1 macrophages in response to stimulation with PAMPs such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and/or cytokines such as TNF and IFNγ. M1 macrophages express high level of MHC-II, CD86, CD40, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), MCP-1, TNFα, IL-1β, IL-12 and IL-6. M1 macrophages mediate excessive inflammatory responses, cytotoxicity and tissue damage. In contrast, macrophages are polarized into M2 macrophages in response to stimulation with cytokines and growth factors such as IL-4, TGF-β, IL-13, IL-10 and M-CSF. M2 macrophages express CD163, CD206 and CD36 surface markers, intracellular arginase-1 and produce cytokines such as TGF-β, IL-10 and IL-6. M2 macrophages promote anti-inflammatory and immune suppressive responses as well as tissue healing.

However, several studies suggest that differentiation of M0 macrophages to M1 and M2 subsets is an oversimplification of macrophages phenotypes where different environmental stimuli lead to differentiation of sub-groups within each subset [24,25]. For example, M2 macrophages are sub-grouped as M2a (induced by IL-4 and IL-10), M2b (induced by toll-like receptors (TLR), and IL-1 receptor (IL-1R), and M2c (induced by IL-10) [26–29]. In addition, recent proteomic and transcriptomic studies have provided evidence for the phenotypic heterogeneity of macrophages based on different stimuli, suggesting that multiple phenotypes could exist during course of infection or inflammation [30–32]. Analysis of the functional responses of the different phenotypes of macrophages will be critical in understanding the pathogenesis of several infectious and inflammatory human diseases including ehrlichiosios.

M1 and M2 Macrophages Influence Innate Immunity and Outcome of Ehrlichia Infection

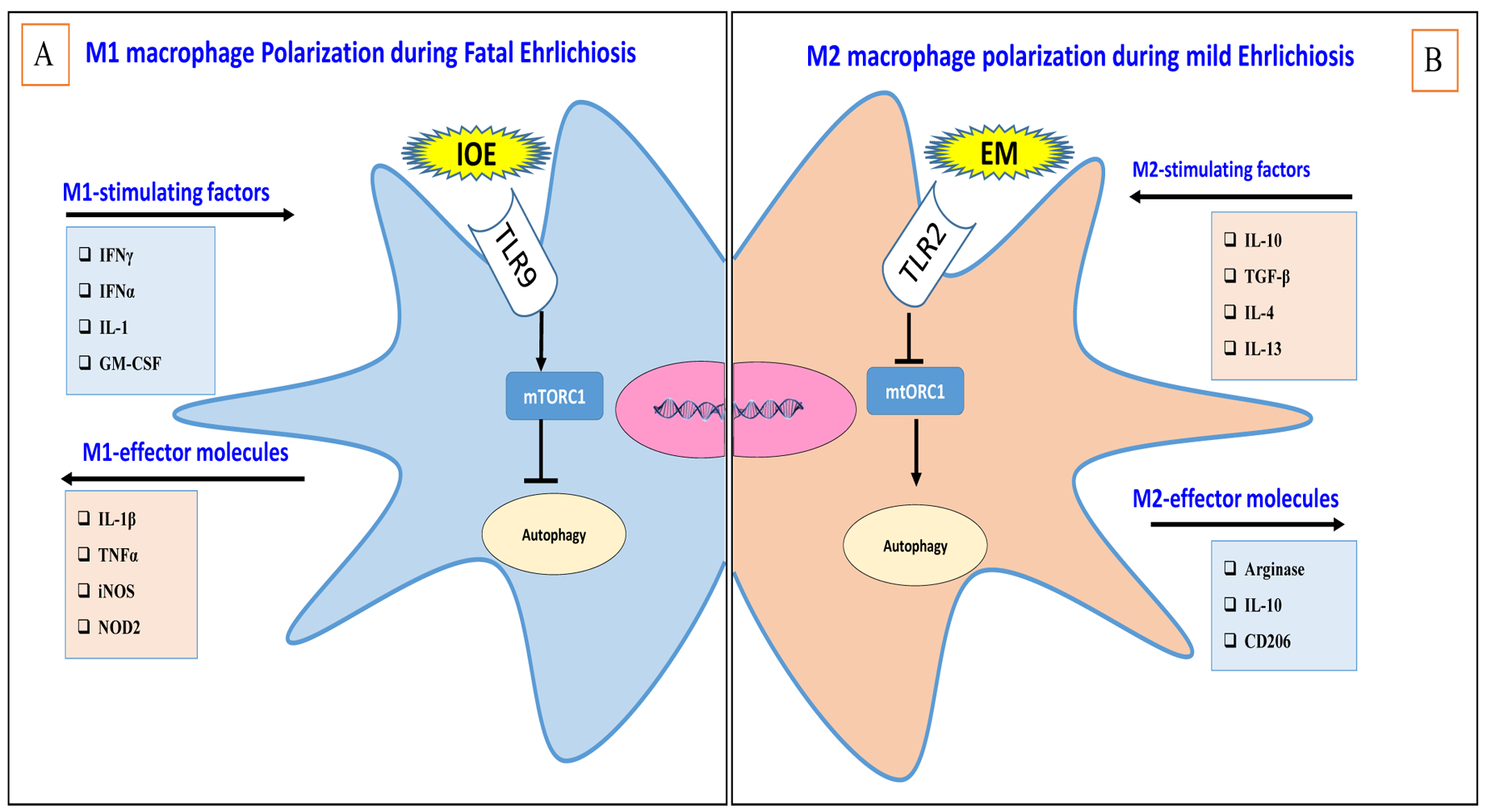

Our study has found that in vitro infection of unprimed primary bone marrow derived macrophages (BMM) with highly virulent Ixodes Ovatus Ehrlichia (IOE) (the causative agent of fatal murine ehrlichiosis), or mildly virulent Ehrlichia muris (the causative agent of mild murine ehrlichiosis) induce polarization of BMM into M1 and M2 phenotypes, respectively [25]. IOE-induced polarization of macrophages into M1 phenotype is rather interesting since Ehrlichia species do not express LPS [33], which is an important pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) that primes macrophages into M1 phenotype [34]. Moreover, cells infected with both IOE or E. muris do not provide significant levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10 that could promote M1/M2 polarization via autocrine/paracrine signals [25]. Nonetheless, how IOE or E. muris trigger M1 and M2 polarization, sequentially, and what are the ehrlichial PAMPs associated with these processes remains obscure. Using murine model of mild and fatal ehrlichiosis, we have further showed that Ehrlichia-induced liver damages and sepsis linked with accumulation of infiltrating pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages/monocytes in the liver [25]. Accumulation of monocyte-derived M1 macrophages and their production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and Granzyme B in the liver of IOE-infected mice coincided with organ damage, dysfunction, and high bacterial burden [35–38] (Figure 2A). In contrast, mild ehrlichiosis is associated with polarization of macrophages into M2 phenotypes, which are important in the resolution phases of inflammation. Notably, we found that M2 cells in E. muris-infected mice accumulated at initial site of infection, peritoneum, which was associated with effective bacterial clearance, limited inflammation, and minimal liver injury (Figure 2B). The differences in bacterial replication in IOE and EM-infected mice and its correlation with macrophages polarization suggest that differentiation of macrophages into M1/M2 cells influence the host immune response and outcome of infection [25].

Figure 2: Macrophage polarization during mild and fatal ehrlichiosis.

A. Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages are likely induced during fatal ehrlichiosis by inflammatory cytokines and factors produced by IOE infection (e.g., IFNγ, TNF-α, IL-1 and GM-CSF). Infection of macrophages with IOE also triggers TLR9 signaling that possibly lead to polarization of M1 cells via activation of mTORC1 and inhibition of autophagy. M1 cells produce oxidative molecules such as nitric oxide (NO), and inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, and IL-1β), causing immunopathology. B. Anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages are likely induced during mild ehrlichiosis via early production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β). It is possible that TLR2 signaling or other factors inhibit mTORC1 activation, which leads to autophagy induction and M2 polarization. M2 macrophages produce arginase and anti-inflammatory cytokines, which mediate tissue remodeling and anti-inflammatory responses.

Macrophages Polarization Influence Adaptive Immunity against Ehrlichia

Macrophages as innate immune and antigen presenting cells are key factors that regulate the phenotype and function of adaptive immune responses against pathogens. Previous studies found that M1 macrophages promote differentiation of naive CD4 T cells into Th1 or Th17 phenotypes via production of Th1- or Th17- promoting cytokines as well as interferon regulatory 5 (IRF5) signaling [39]. Cross talk between Th1 or Th17 cells producing IFNγ and IL-17, respectively, can also promote macrophage polarization into M1 type via a positive feedback loop. Although, this M1-Th17 axis can mediate the clearance of pathogens, they can also increase inflammation and produce tissue injury [40]. Our murine studies demonstrate that fatal ehrlichiosis is linked to induction and expansion of Th17 and presence of high serum level of IL-17 in infected mice at day 7 post-infection (p.i.), which followed by death on days 8–10 p.i. This response in lethally (IOE) infected mice correlate with systemic cytokine and chemokine storm marked by significant increase in the serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines that known to promote M1-Th17 differentiation such as GM-CSF, IL-1 β, and IL-6 compared to uninfected or non-lethally (E. muris)- infected mice [25]. GM-CSF is known to polarize macrophages into M1-type, while IL-1β and IL-6 support initiation and increase of antigen-specific Th1 and Th17 cell responses [41]. Our data suggest that M1-Th17 axis likely play a role in the pathogenesis of fatal ehrlichiosis by promoting inflammation and host cell death [25]. Farther investigation required for understanding the role of Th17 to host protection during Ehrlichia and disease pathogenesis.

Regulation of macrophages polarization via mTORC1 activation and Autophagy.

Previous data illustrated a significant association between macrophages polarization and autophagic activity. Many studies in cancer models have demonstrated that M2-type macrophages regulated after activating autophagy, however, the connection with M1 or M2 was contextual [42,43]. For instance, deficiency of autophagy protein Atg5 promotes M2 polarization activation, suggesting that autophagy induction negatively regulate M2 polarization [44–46]. However, in our Ehrlichia infection model, we found that polarization and expansion of M2 macrophages in E. muris-infected mice (i.e., mild ehrlichiosis) is linked to induction of autophagy, while M1 polarization in IOE-infected mice (fatal ehrlichiosis) was associated with inhibition of autophagy [25,47] (Figure 2B). Mechanistically, our data demonstrate that inhibition of autophagy and M1 polarization was due to mTORC1 activation. Blocking mTORC1 signaling in IOE-infected macrophages enhanced autophagy and decreased polarization of M1 macrophages, suggesting that mTORC1 is a key regulator of m1 polarization during Ehrlichia-induced sepsis (Figure 2A).

These data suggest that metabolic state is a key factor in macrophage polarization in ehrlichiosis, which is consistent with conclusion made in other models [25]. For example, recent studies demonstrated that activated macrophages are glycolytic cells with different metabolic status of M1 and M2 cells [48]. Activation of M1 macrophages is linked to aerobic glycolysis, which lead to increased glucose uptake. Additionally, M1 polarization has been associated with the induction of a pentose phosphate pathway, which provides NADPH for the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and attenuates mitochondrial respiratory change, resulting in increased ROS production. In contrast, M2 macrophage utilizes fatty acid oxidation [49]. One of the mechanisms of differential metabolic states between M1 and M2 macrophages has been identified as a switch in the expression of phosphofructokinase 2 isoenzymes that appears to be a common event after LPS/IFN-γ or TLR 2, 3, 4, and 9 stimulation (M1 pathway) [48]. Nevertheless, although the differences in the metabolic states of M1 and M2 are well accepted, the underlying mechanisms involved in switching between metabolic states are not well understood.

To this end, other studies have shown that a key molecule of signal transduction pathway Akt also contributes to macrophage polarization, depending on its isoform. Akt1 isoform ablation in macrophages produces an M1 macrophage phenotype, and Akt2 ablation results in an M2 phenotype [50]. Akt2−/− mice are more resistant to LPS-induced endotoxin shock and to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis than wild-type mice, whereas Akt1 ablation renders the mice more sensitive to LPS- induced endotoxin shock [50]. Other studies suggested that the cAMP response element-binding protein is critical transcription factor for up-regulating IL-10 and arginine-1, markers of M2 phenotype, while suppressing polarization of M1 cells. This conclusion is based on data showing that deletion of two cAMP response element binding protein-binding sites from the C/EBPβ gene promoter blocks the downstream induction of anti-inflammatory genes associated with M2-like macrophage activation [51]. Other study demonstrated an association between increased AMP protein kinase activity and a decreased polarization of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages [52]. Similarly, AMP protein kinase α1−/− macrophages fail to differentiate into anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype [53].

miRNA has also been implicated in macrophages polarization. miRNA let-7c promotes M2 macrophage polarization and suppresses M1 polarization [54]. Similarly, miR-124 decreases M1 polarization and enhances M2 polarization in bone marrow derived macrophages from mice. This conclusion is supported by data showing that overexpression of miR-124 reduces expression of M1 phenotypic markers CD45, CD11b, F4/80, MHCII, and CD86, but increases the expression of arginine 1, an M2 phenotypic marker. Finally, miR-223 deficient macrophages were highly susceptible to LPS stimulation and M1 polarization, which was mediated via Pknox1, a proinflammatory gene that was identified in these studies as a target of miR- 223 [55].

ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) family member protein also plays a key role in macrophage polarization from M1 to M2. ABCF1 expression enhances TRIF-dependent anti-inflammatory cytokine and IFNβ production by polarizing macrophages to an M2 phenotype. In contract, the loss of ABCF1 leads to pro-inflammatory cytokine production by polarizing macrophages to an M1 phenotype [56].

Finally, it was suggested that pattern recognition receptors such as toll like receptors (TLRs) and cytosolic receptors such as Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2) regulate M1/M2 polarization. Employing our murine models of mild ehrlichiosis, we have found that M2 polarization in mice infected with mildly virulent E. muris is linked to upregulation of TLR2 signaling, protective immunity, and development of mild disease. In contrast, M1 polarization in mice infected with highly virulent IOE is associated with NOD2 and TLR9 signaling, immunopathology, and development of severe liver damage and sepsis [57]. Notably, recently we have demonstrated that TLR9 signaling causes mTORC1 activation and activation of deleterious inflammasome activation that cause liver injury [47]. Since mTORC1 activation trigger M1 polarization, our data suggest that TLR9 signaling during fatal Ehrlichia infection induces M1 polarization. However, it is unclear whether NOD2 and TLR2 signaling directly induce M2 and M1 polarization during IOE and E. muris infection and the mechanisms involved. Previous studies have demonstrated that TLR2 may induce M2 polarization via stimulation of autophagic machinery [58,59]. On the other hand, NOD2 signaling in human macrophages may cause M1 polarization by promoting expression of proinflammatory cytokines [60]. However, other studies did not support this conclusion as NOD2 knockout did not cause any changes in the macrophage phenotype [25,61]. Nevertheless, the impact of differential sensing of intracellular pathogens by PRRs such as TLRs or NOD on macrophages polarization and the mechanisms involved require further examination.

In conclusion, using two different types of Ehrlicha as an infection model for fatal and mild ehrlichiosis, are excellent tools to understand the differences and participation of macrophages in both types of infection. We argue that the induction of M2 polarization at early stage of infection with mildly virulent E. muris control the infection by activating homeostatic and anti-inflammatory responses. On the other hand, we conclude that polarization of M1 cells during infection with highly virulent IOE promote immunopathology and tissue injury, while eliminating replicating bacteria, via multiple effector mechanisms including production of iNOS, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and activation of inflammatory antigen-specific Th17 cells.

The Future Direction of Macrophages Polarization

A better understanding of macrophages differentiation into M1 or M2 have become essential for understanding the pathogenesis of several infectious, inflammatory and autoimmune diseases as well as cancer development and metastasis. Further studies are necessary to determine the molecular and cellular mechanisms that regulate polarization of macrophages and their plasticity during courses of infectious diseases. Information from these studies could be applied towards design of novel immunotherapeutic approaches. For example, approaches that control M1 polarization could attenuate excessive inflammatory responses and tissue damage. Similarly, therapeutic approaches that prevent polarization of M2 macrophages could be helpful for treatment of infectious or non-infectious diseases associated with immunosuppression such as cancer.

Funding

This study was funded by the NIH Grant R56 AI097679.

References

- 1.Ismail N, Bloch KC, McBride JW. Human ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 2010. March 1;30(1):261–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavelites JJ, Prahlow JA. Fatal human monocytic ehrlichiosis: a case study. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology. 2011. September 1;7(3):287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mott J, Barnewall RE, Rikihisa Y. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and Ehrlichia chaffeensis reside in different cytoplasmic compartments in HL-60 cells. Infection and Immunity. 1999. March 1;67(3):1368–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aizarani N, Saviano A, Mailly L, Durand S, Herman JS, Pessaux P, et al. A human liver cell atlas reveals heterogeneity and epithelial progenitors. Nature. 2019. August;572(7768):199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Büchau AS, Gallo RL. Innate immunity and antimicrobial defense systems in psoriasis. Clinics in Dermatology. 2007. November 1;25(6):616–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabas I, Lichtman AH. Monocyte-macrophages and T cells in atherosclerosis. Immunity. 2017. October 17;47(4):621–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ricardo SD, Van Goor H, Eddy AA. Macrophage diversity in renal injury and repair. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008. November 3;118(11):3522–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakubzick CV, Randolph GJ, Henson PM. Monocyte differentiation and antigen-presenting functions. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2017. June;17(6):349–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epelman S, Lavine KJ, Beaudin AE, Sojka DK, Carrero JA, Calderon B, et al. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity. 2014. January 16;40(1):91–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013. January 24;38(1):79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto D, Chow A, Noizat C, Teo P, Beasley MB, Leboeuf M, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013. April 18;38(4):792–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutterwala FS, Noel GJ, Clynes R, Mosser DM. Selective suppression of interleukin-12 induction after macrophage receptor ligation. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1997. June 2;185(11):1977–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutterwala FS, Noel GJ, Salgame P, Mosser DM. Reversal of proinflammatory responses by ligating the macrophage Fcγ receptor type I. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998. July 1;188(1):217–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhuang G, Meng C, Guo X, Cheruku PS, Shi L, Xu H, et al. A novel regulator of macrophage activation: miR-223 in obesity-associated adipose tissue inflammation. Circulation. 2012. June 12;125(23):2892–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Li R, Peng Z, Hu B, Rao X, Li J. [Corrigendum] HMGB1 participates in LPS-induced acute lung injury by activating the AIM2 inflammasome in macrophages and inducing polarization of M1 macrophages via TLR2, TLR4, and RAGE/NF-κB signaling pathways. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2020. May 1;45(5):1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutknecht MF, Bouton AH. Functional significance of mononuclear phagocyte populations generated through adult hematopoiesis. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2014. December;96(6):969–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minutti CM, Knipper JA, Allen JE, Zaiss DM. Tissue-specific contribution of macrophages to wound healing InSeminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2017. January 1 (Vol. 61, pp. 3–11). Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012. March 1;122(3):787–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gouwy M, Ruytinx P, Radice E, Claudi F, Van Raemdonck K, Bonecchi R, et al. CXCL4 and CXCL4L1 differentially affect monocyte survival and dendritic cell differentiation and phagocytosis. PloS one. 2016;11(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills CD. Macrophage arginine metabolism to ornithine/urea or nitric oxide/citrulline: a life or death issue. Critical Reviews™ in Immunology. 2001;21(5). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell L, Saville CR, Murray PJ, Cruickshank SM, Hardman MJ. Local arginase 1 activity is required for cutaneous wound healing. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2013. October 1;133(10):2461–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boldrick JC, Alizadeh AA, Diehn M, Dudoit S, Liu CL, Belcher CE, et al. Stereotyped and specific gene expression programs in human innate immune responses to bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002. January 22;99(2):972–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nau GJ, Richmond JF, Schlesinger A, Jennings EG, Lander ES, Young RA. Human macrophage activation programs induced by bacterial pathogens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002. February 5;99(3):1503–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. The Journal of Immunology. 2006. November 15;177(10):7303–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haloul M, Oliveira ER, Kader M, Wells JZ, Tominello TR, El Andaloussi A, et al. mTORC1-mediated polarization of M1 macrophages and their accumulation in the liver correlate with immunopathology in fatal ehrlichiosis. Scientific Reports. 2019. October 1;9(1):1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rőszer T Understanding the mysterious M2 macrophage through activation markers and effector mechanisms. Mediators of inflammation. 2015;2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benoit M, Desnues B, Mege JL. Macrophage polarization in bacterial infections. The Journal of Immunology. 2008. September 15;181(6):3733–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gordon S Alternative activation of macrophages. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2003. January;3(1):23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wynn TA, Barron L. Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis InSeminars in Liver Disease 2010. August (Vol. 30, No. 03, pp. 245–257). © Thieme Medical Publishers; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2011. November;11(11):723–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petre G, Atifi ME, Millet A. Proteomic signature reveals modulation of human macrophage polarization and functions under differing environmental oxygen conditions. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2017. December 1;16(12):2153–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das A, Sinha M, Datta S, Abas M, Chaffee S, Sen CK, et al. Monocyte and macrophage plasticity in tissue repair and regeneration. The American Journal of Pathology. 2015. October 1;185(10):2596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin M, Rikihisa Y. Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum lack genes for lipid A biosynthesis and incorporate cholesterol for their survival. Infection and Immunity. 2003. September 1;71(9):5324–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koo SJ, Garg NJ. Metabolic programming of macrophage functions and pathogens control. Redox Biology. 2019. April 20:101198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rust C, Gores GJ. Apoptosis and liver disease22. The American Journal of Medicine. 2000. May 1;108(7):567–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sass G, Koerber K, Bang R, Guehring H, Tiegs G. Inducible nitric oxide synthase is critical for immune-mediated liver injury in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001. February 15;107(4):439–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nathan C, Ding A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell. 2010. March 19;140(6):871–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwakiri Y Nitric oxide in liver fibrosis: The role of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Clinical and Molecular Hepatology. 2015. December;21(4):319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krausgruber T, Blazek K, Smallie T, Alzabin S, Lockstone H, Sahgal N, et al. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and T H 1-T H 17 responses. Nature Immunology. 2011. March;12(3):231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakai K, He YY, Nishiyama F, Naruse F, Haba R, Kushida Y, et al. IL-17A induces heterogeneous macrophages, and it does not alter the effects of lipopolysaccharides on macrophage activation in the skin of mice. Scientific Reports. 2017. September 29;7(1):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lacey DC, Achuthan A, Fleetwood AJ, Dinh H, Roiniotis J, Scholz GM, et al. Defining GM-CSF–and macrophage-CSF–dependent macrophage responses by in vitro models. The Journal of Immunology. 2012. June 1;188(11):5752–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanjurjo L, Aran G, Téllez É, Amézaga N, Armengol C, López D, et al. CD5L promotes M2 macrophage polarization through autophagy-mediated upregulation of ID3. Frontiers in Immunology. 2018. March 12;9:480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang J, Zhang L, Yu C, Yang XF, Wang H. Monocyte and macrophage differentiation: circulation inflammatory monocyte as biomarker for inflammatory diseases. Biomarker Research. 2014. December;2(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ye X, Zhou XJ, Zhang H. Exploring the role of autophagy-related gene 5 (ATG5) yields important insights into autophagy in autoimmune/autoinflammatory diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 2018. October 17;9:2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen TA, Wang JL, Hung SW, Chu CL, Cheng YC, Liang SM. Recombinant VP1, an Akt inhibitor, suppresses progression of hepatocellular scarcinoma by inducing apoptosis and modulation of CCL2 production. PloS One. 2011;6(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen P, Cescon M, Bonaldo P. Autophagy-mediated regulation of macrophages and its applications for cancer. Autophagy. 2014. February 26;10(2):192–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kader M, El-Azher M, Vorhauer J, Kode BB, Wells JZ, Stolz D, et al. MyD88-dependent inflammasome activation and autophagy inhibition contributes to Ehrlichia-induced liver injury and toxic shock. PLoS Pathogens. 2017. October 19;13(10):e1006644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodríguez-Prados JC, Través PG, Cuenca J, Rico D, Aragonés J, Martín-Sanz P, et al. Substrate fate in activated macrophages: a comparison between innate, classic, and alternative activation. The Journal of Immunology. 2010. July 1;185(1):605–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galván-Peña S, O’Neill LA. Metabolic reprograming in macrophage polarization. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014. September 2;5:420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arranz A, Doxaki C, Vergadi E, de la Torre YM, Vaporidi K, Lagoudaki ED, et al. Akt1 and Akt2 protein kinases differentially contribute to macrophage polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012. June 12;109(24):9517–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruffell D, Mourkioti F, Gambardella A, Kirstetter P, Lopez RG, Rosenthal N, et al. A CREB-C/EBPβ cascade induces M2 macrophage-specific gene expression and promotes muscle injury repair. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009. October 13;106(41):17475–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sag D, Carling D, Stout RD, Suttles J. Adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase promotes macrophage polarization to an anti-inflammatory functional phenotype. The Journal of Immunology. 2008. December 15;181(12):8633–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mounier R, Théret M, Arnold L, Cuvellier S, Bultot L, Göransson O, et al. AMPKα1 regulates macrophage skewing at the time of resolution of inflammation during skeletal muscle regeneration. Cell Metabolism. 2013. August 6;18(2):251–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Banerjee S, Xie N, Cui H, Tan Z, Yang S, Icyuz M, et al. MicroRNA let-7c regulates macrophage polarization. The Journal of Immunology. 2013. June 15;190(12):6542–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ponomarev ED, Veremeyko T, Barteneva N, Krichevsky AM, Weiner HL. MicroRNA-124 promotes microglia quiescence and suppresses EAE by deactivating macrophages via the C/EBP-α–PU. 1 pathway. Nature Medicine. 2011. January;17(1):64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arora H, Wilcox SM, Johnson LA, Munro L, Eyford BA, Pfeifer CG, et al. The ATP-binding cassette gene ABCF1 functions as an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme controlling macrophage polarization to dampen lethal septic shock. Immunity. 2019. February 19;50(2):418–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chattoraj P, Yang Q, Khandai A, Al-Hendy O, Ismail N. TLR2 and Nod2 mediate resistance or susceptibility to fatal intracellular Ehrlichia infection in murine models of ehrlichiosis. PloS One. 2013;8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang CP, Su YC, Hu CW, Lei HY. TLR2-dependent selective autophagy regulates NF-κB lysosomal degradation in hepatoma-derived M2 macrophage differentiation. Cell Death & Differentiation. 2013. March;20(3):515–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang CP, Su YC, Lee PH, Lei HY. Targeting NFKB by autophagy to polarize hepatoma-associated macrophage differentiation. Autophagy. 2013. April 4;9(4):619–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hedl M, Yan J, Abraham C. IRF5 and IRF5 disease-risk variants increase glycolysis and human M1 macrophage polarization by regulating proximal signaling and Akt2 activation. Cell Reports. 2016. August 30;16(9):2442–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Awad F, Assrawi E, Jumeau C, Georgin-Lavialle S, Cobret L, Duquesnoy P, et al. Impact of human monocyte and macrophage polarization on NLR expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. PloS One. 2017;12(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]