Abstract

Hemichorea and other hyperkinetic movement disorders are a rare presentation of stroke, usually secondary to deep infarctions affecting the basal ganglia and the thalamus. Chorea can also result from lesions limited to the cortex, as shown in recent reports. Still, the pathophysiology of this form of cortical stroke-related chorea remains unknown. We report 4 cases of acute ischemic cortical strokes presenting as hemichorea, with the infarction being limited to the parietal and insular cortex in perfusion computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging. These cases suggest potential dysfunction of pathways connecting these cortical regions with the basal ganglia.

Key Words: Chorea, Stroke, Cortex, Insula

Introduction

Hyperkinetic movement disorders are a rare presentation of stroke.1 , 2 The pathophysiology of these abnormal movements remains uncertain.1, 2, 3 They are either seen in the acute phase of mostly thalamic infarction as a result of deafferentation or in the chronic phase of stroke involving the contralateral basal ganglia, especially the subthalamic and lentiform nucleus.1, 2, 3, 4 More recently, cortical ischemic lesions have added to locations causing chorea in stroke.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 We present 4 cases of patients that suffered an acute hemichorea secondary to isolated parietal and insular cortical acute ischemic strokes, highlighting the role of the cortex in acute hyperkinetic disorders.

Results

We describe four patients, three females and one male, mean age 72 years old. All of the patients presented hemichorea within 24 h of symptom onset, which was the primary presenting symptom in 3 of them. All of them had normal laboratory results, including glycemia, thyroid function, and blood cell count. Two of the cases had a perfusion computed tomography (CT) scan done during the hyperacute evaluation, and all four underwent a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing cortical frontal, parietal, and/or insular infarctions and sparing of the basal ganglia. Three patients received acute revascularization for the stroke, two mechanical thrombectomy, and one iv fibrinolysis, and one did not due to excessive time since symptom onset upon arrival.

Case 1

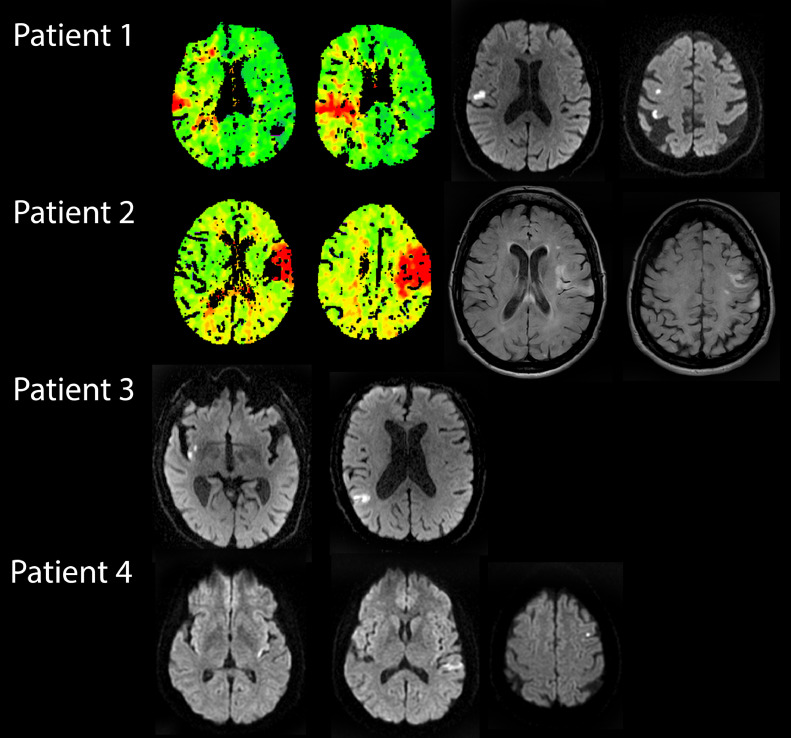

A 74-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital due to acute onset dysarthria, left-hand hypesthesia, with agraphestesia, and choreoathetosic movements of the left arm. A multimodal CT study including CT perfusion (CTP) during the symptomatic phase, revealed right cortical hypoperfusion due to an occlusion of the right distal middle cerebral artery (MCA, M3 branch) with normal perfusion of the basal ganglia (Fig. 1 , top row, first and second images). After iv thrombolysis, the hyperkinetic movements ceased. A control MRI showed an acute patchy ischemic stroke in the right parietal and posterior frontal cortices, sparing the basal ganglia (Fig. 1, top row, third and fourth images).

Fig. 1.

Perfusion computed tomography (CTP) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of all 4 patients. The first two images on top row show a CTP of patient 1 while symptomatic, with delayed perfusion in the right fronto-parietal cortex, as shown in the time-to-peak (TTP) with normal perfusion of deep structures; third and fourth images show follow-up diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) MRI of the same patient after symptom resolution with patchy acute ischemic lesions in the right convexity, sparing the basal ganglia. The two images to the left on the second row show TTP CTP of patient 2, during the first asymptomatic phase, with delayed perfusion on the left insular, frontal and parietal cortex with normal perfusion of basal ganglia; the two images to the right show MRI fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences after the onset of right hemichoreic movements, where ischemic left insular, frontal, and postcentral gyrus lesions can be appreciated; note the absence of compromise of the deep territory. The two images on the third row consist of the DWI MRI sequences of patient 3, performed while symptomatic, demonstrating a right hemispheric ischemic lesion on the posterior insula and parietal cortex, sparing the basal ganglia. Bottom row shows three DWI MRI images of patient 4, performed 24 hours after symptom onset, with ischemic lesions in the left posterior insular and parietal cortex, also without involvement of deep gray matter structures.

Case 2

A 79-year-old woman with unremarkable medical history was brought to our facility due to acute aphasia and right hemiparesis. A multimodal CT showed an M2 branch occlusion of the left MCA, and a corresponding focal perfusion deficit without basal ganglia involvement, as well as a thrombosed aortic arch (Fig. 1, second row, first and second images). She underwent urgent endovascular treatment with successful revascularization and partial clinical improvement. Two days after the procedure, the deficits worsened and presented abnormal choreic movements of the right limbs, that ceased with iv haloperidol. The MRI showed an acute ischemic stroke affecting the left insular and parietal cortex and complete sparing of the basal ganglia (Fig. 1, second row, third and fourth images). At discharge, the patient recovered completely and did not need chronic neuroleptic treatment.

Case 3

A 83-year-old man presented with sudden onset left hemichorea. The CT scan revealed no early ischemic lesions, and there was no proximal occlusion on the CT angiogram. A subsequent MRI confirmed an acute ischemic stroke affecting the right parietal and insular cortex, with complete sparing of the basal ganglia (Fig. 1, third row). The hyperkinetic symptoms self-limited in the first 48h without any pharmacologic treatment and he was started on anticoagulation due to paroxysmal atrial fibrillation during the etiologic investigation.

Case 4

A 59-year-old woman without relevant past history presented to the emergency department with high-amplitude right-sided hemichorea (that included the face), and Wernicke's aphasia that had begun 45 min before (Online Supplementary material, video 1). The abnormal movements remitted with 2,5 mg i.v. haloperidol. A head CT scan showed no abnormalities, and the CT-angiogram revealed a distal left M2 occlusion; CT-perfusion could not be performed as this patient was admitted during the Covid-19 pandemic and the acute neuroimaging protocol was simplified at that time. Complete reperfusion was achieved with mechanical thrombectomy. An MRI 24 h later showed a cortical acute ischemic lesion in the insular, temporal, and parietal cortex (Fig. 1, fourth row). She was discharged asymptomatic soon after.

Discussion

Sudden hyperkinetic movements such as hemichorea are a rare presentation of acute ischemic stroke,1 , 2 usually involving a disfunction of the subthalamic nucleus and other basal ganglia structures.1, 2, 3, 4 We report four cases of such abnormal movements secondary to parietal-insular cortical ischemic stroke as documented by perfusion CT scans during the symptomatic phase and/or DWI-MRI, and with no other laboratory or imaging abnormalities pointing to alternative causes.

The presence of stroke-associated abnormal hyperkinetic movements such as chorea has been known for long, often due to the infarction of deep brain structures including the subthalamic nucleus as well as other basal ganglia structures,1, 2, 3, 4 being the suggested pathophysiology a diminished activity of the “indirect pathway” in the classical basal ganglia circuitry scheme.10 In other instances chorea presents as the result of sensory deafferentation in the setting of thalamic infarction.

In the past few years, growing literature has been published reporting cases of abnormal movements such as chorea or ballism with ischemic strokes only affecting the cerebral cortex and not the basal ganglia.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Participation of the parietal (and also frontal) cortex has previously been suggested in the setting of acute ischemic stroke,5, 6, 7, 8, 9 in possible relation to an impaired hyperdirect pathway of the motor control system.5 According to this, a decreased direct stimulus from the cortex would result in disinhibition of the thalamus due to hypofunction of the subthalamic nucleus,11 causing a disbalance between the direct and indirect pathways. Control of chorea with haloperidol in one of the cases we report would fit with this notion. Alternatively, sensory loss through reduced input from sensory to motor cortex, as seen in thalamic or parietal cortex lesions, might also play a role in the origin of hyperkinetic contralateral movements.12 Previously reported cases could not rule out hypoperfusion of the basal ganglia due to a proximal occlusion that subsequently recanalized as the origin of the symptoms.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 , 13 In two of our cases we have evidence of limited cortical hypoperfusion during the symptomatic phase, with sparing of the basal ganglia, and all the cases were confirmed to have only cortical infarctions on MRI, suggesting a fundamental contribution of the cortex.

The insular cortex has been described to be related with somatomotor and elaborate motor tasks and motor plasticity in poststroke recovery of motor functions in functional imaging studies.14 However, we are not aware of previous reports of insula-basal ganglia connections related to hyperkinetic movements. In our series, the insular infarction, although present in the majority of the cases (3 out of 4), always occurred accompanied by ischemic lesions in the parietal and/or frontal cortices. Previous described cases also present with an associated insular infarction.5 For those reasons, it is doubtful that the insular region had any role in the symptoms, and the presence of insular lesions could be just the result of poor collateral circulation in the insula in patients with large vessel occlusions involving the middle cerebral artery territory.15

In all of our patients, symptoms ceased rapidly after stroke revascularization. This finding is in line with previous publications,13 , 16 suggesting a good prognosis, probably due to preservation of the deep structures circuitry integrity. Hence, recognition of acute chorea as a possible presentation of stroke is important for a timely and effective treatment in these cases.

Conclusions

Although it is an uncommon form of presentation, a sudden onset hemichorea should be considered an acute stroke until proven otherwise and treated as such. These cases support the theory of a relevant role of parietal (and possibly insular) cortex in the origin of abnormal hyperkinetic movements, and a possible functional connection with the basal ganglia.

Funding

This study is not funded.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105150.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Electronic supplementary material. Video 1. Video of patient number 4 upon admission to the hospital. Note the wide amplitude choreic movements in her right limbs. Although the patient presented with aphasia, she seemed to be unaware of the abnormal movements. After complete symptomatic resolution, she was specifically asked about the hyperkinetic movements and she admitted of being totally unaware of them and was even surprised and amused when we showed this video to her.

References

- 1.Mehanna R., Jankovic J. Movement disorders in cerebrovascular disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(6):597–608. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghika-Schmid F., Ghika J., Regli F., Bogousslavsky J. Hyperkinetic movement disorders during and after acute stroke: The Lausanne Stroke Registry. J Neurol Sci. 1997;146(2):109–116. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(96)00290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park J. Movement disorders following cerebrovascular lesion in the basal ganglia circuit. J Mov Disord. 2016;9(2):71–79. doi: 10.14802/jmd.16005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang K.J., Hong I.K., Ahn T. Cortical hemichorea–hemiballism. J Neurol. 2013;260:2986–2992. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotroneo M., Ciacciarelli A., Cosenza D. Hemiballism: Unusual clinical manifestation in three patients with frontoparietal infarct. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;188 doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacob S., Gupta H.V. Delayed hemichorea following temporal-occipital lobe infarction. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2016;19(6):414. doi: 10.7916/D8DB821H. https://doi.org/eCollection 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malhotra K., Khunger A. Cortical stroke and hemichorea. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2017;7:444. doi: 10.7916/D8BK1CWK. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss S., Rafie D., Nimma A., Romero R., Hanna P.A. Pure cortical stroke causing hemichorea-hemiballismus. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;28(10) doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung S.J., Im J., Lee M.C., Kim J.S. Hemichorea after stroke: CLINICAL-radiological correlation. J Neurol. 2004;251:725–729. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander G.E., DeLong M.R., Strick P.L. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357‐381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nambu A. A new dynamic model of the cortico-basal ganglia loop. Prog Brain Res. 2004;143:461–466. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)43043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navnika G., Sanjay P. Post-thalamic stroke movement disorders: a systematic review. Eur Neurol. 2018;79:303–314. doi: 10.1159/000490070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel A.R., Patel A.R., Desai S. Acute hemiballismus as the presenting feature of parietal lobe infarction. Cureus. 2019;11(5):e4675. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nieuwenhuys R. The insular cortex: a review. Prog Brain Res. 2012;195:123–163. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laredo C., Zhao Y., Rudilosso S. Prognostic significance of infarct size and location: the case of insular stroke. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9498. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27883-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizushima N., Park-Matsumoto Y.C., Amakawa T., Hayashi H. A case of hemichorea-hemiballism associated with parietal lobe infarction. Eur Neurol. 1997;37:65–66. doi: 10.1159/000117408. https://doi.org/1159/000117408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Electronic supplementary material. Video 1. Video of patient number 4 upon admission to the hospital. Note the wide amplitude choreic movements in her right limbs. Although the patient presented with aphasia, she seemed to be unaware of the abnormal movements. After complete symptomatic resolution, she was specifically asked about the hyperkinetic movements and she admitted of being totally unaware of them and was even surprised and amused when we showed this video to her.