Abstract

Pre-pregnancy maternal obesity is associated with adverse outcomes for the offspring, including increased incidence of neonatal bacterial sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis. We recently reported that umbilical cord blood (UCB) monocytes from babies born to obese mothers generate a reduced IL6/TNFα response to Toll-like receptors 1/2 and 4 ligands compared to those collected from lean mothers. These observations suggest altered development of the offspring’s immune system, which in turn results in dysregulated function. We, therefore, investigated transcriptional and epigenetic differences within UCB monocytes stratified by pre-pregnancy maternal body mass index (BMI). We show that UCB monocytes from babies born to obese mothers generate a dampened response to LPS stimulation compared to those born to lean mothers, at the level of secreted immune mediators and transcription. Since gene expression profiles of resting UCB monocytes from both groups were comparable, we next investigated the role of epigenetic differences. Indeed, we detected stark differences in methylation levels within promoters/regulatory regions of genes involved in Toll-like receptor signaling in resting UCB monocytes. Interestingly, DNA methylation status of resting cells was highly predictive of transcriptional changes post LPS stimulation, suggesting cytosine methylation as one of the dominant mechanisms driving functional inadequacy in UCB monocytes obtained from babies born to obese mothers. These data highlight a potentially critical role of maternal pregravid obesity-induced epigenetic changes in influencing the function of offspring’s monocytes at birth. These findings further our understanding of mechanisms that explain the increased risk of infection in neonates born to mothers with high pre-pregnancy BMI.

Keywords: Pregravid obesity, neonates, umbilical cord blood monocytes, DNA Methylation, Transcription

INTRODUCTION

Almost 37% of women of childbearing age are categorized as obese, making obesity one of the most common co-morbidities during pregnancy (1). It is well established that a high pre-pregnancy (pregravid) body mass index (BMI) is associated with detrimental health outcomes for both mother and child (2–4). Maternal complications of pregravid obesity include increased rates of preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, placental abruption, preterm delivery, and cesarean delivery (1). For the fetus, complications include increased risk of stillbirth, abnormal growth, and cardiac/neural tube defects (1, 4). Moreover, neonates born to obese mothers are at increased risk of bacterial sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis, requiring admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (5, 6). Some adverse health outcomes for the offspring persist into adulthood, including increased susceptibility to respiratory infections such as respiratory syncytial virus (7, 8), asthma (9), wheezing (10), cancer (11), type-2 diabetes (12), and cardiovascular disease (13), culminating in an increased risk for all-cause offspring mortality (14).

The aforementioned observations strongly suggest that pregravid obesity disrupts the development and maturation of the offspring’s immune system in utero. This hypothesis is supported by studies in murine models that have shown detrimental effects on the immune system of pups born to obese compared with lean dams (15, 16). Specifically, pups born to obese dams generated disparate IgG (smaller) and IgE (larger) antibody responses following vaccination with ovalbumin (15). If these results are true in humans, they could explain the increased incidence of asthma (9) and wheezing (10) in children born to obese mothers. Additional rodent studies reported greater morbidity and mortality following bacterial infection (Escherichia. coli sepsis and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus. aureus infection) and greater susceptibility to auto-immune encephalitis in pups born to obese dams (16). Lastly, ex-vivo LPS stimulation of colonic lamina propria lymphocytes resulted in increased secretion of inflammatory cytokines IL6, IL1β and IL17, whereas LPS stimulation of splenocytes resulted in decreased levels of TNFα and IL6 in pups born to obese dams(16). Collectively, these data strongly suggest dysregulated immunity in pups born to obese dams where aberrant responses (such as to auto-antigens) are exaggerated while protective anti-microbial responses are reduced. Similarly, a baboon study reported significant changes in the expression of genes involved in antigen presentation, complement and coagulation cascade, leukocyte migration, and B cell receptor signaling, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) collected from infants born to obese compared to lean dams (17).

However, only a few studies have explored the impact of maternal pregravid obesity on neonatal immune function in humans. One study reported that children born to obese mothers have a 16-fold higher risk of having detectable levels of C reactive protein (CRP) after adjusting for BMI, Tanner stages, and gender compared to children born to lean mothers, suggesting that high pregravid maternal BMI results in dysregulated inflammatory responses in the offspring (18). More recently, we have demonstrated that pregravid maternal BMI is associated with a reduced number of umbilical cord blood (UCB) CD4+ T-cells, IL-4 secreting CD4+ T-cells, and a diminished ability of monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells to respond to ex vivo stimulation with LPS (TLR4 ligand) and HKLM/Pam3CSK4 (TLR1/2 ligands) (19). However, the mechanisms that drive these dysregulated processes are unknown.

Therefore, in this study, we sought to investigate the mechanisms underlying the suppressed responses of UCB monocytes collected from babies born to obese mothers following LPS stimulation. We chose to focus on monocytes in light of the critical role they play in host defense during the early neonatal period (20). In addition, monocytes are some of the earliest phagocytic cells in the fetus, appearing as early as week 3 of gestation (21), making them exquisitely sensitive for reprogramming by the maternal metabolic environment. We carried out a combination of functional and genomics analyses to uncover the impact of pregravid obesity on purified UCB monocyte response to LPS. First, we measured differences in cytokine, chemokines and growth factor production between UCB monocytes collected from babies born to obese and lean mothers. We then determined differences in transcriptional activity between these two groups and finally, we assessed differences in DNA methylation. Our analyses revealed significant dampening of immune mediator production coupled with a repressed transcriptional program and changes in levels of methylation in genomic loci that overlap regulatory regions of genes critical for mediating a pro-inflammatory response in UCB monocytes of babies born to obese mothers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This research project was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Boards (IRB) of Oregon Health and Science University and University of California Riverside. All subjects provided signed consent before enrolling in the study. The characteristics of this cohort were described earlier (19). For the studies described in this manuscript, a total 18 umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells (UCBMC) samples collected from non-smoking women without gestational diabetes who had an uncomplicated, singleton gestation were used: eight women with a mean age of 31.25 ± 4.9 years and a pre-pregnancy BMI of 21.8 ± 1.9 kg/m2 (lean); and ten women with a mean age of 30.5 ± 5.6 and a pre-pregnancy BMI of 36.6 ± 4.5 kg/m2 (obese). The racial distribution was as follows: 15 Caucasian, 1 Asian American/Pacific Islander, 1 American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 1 unknown.

Cell separation and purification

UCBMC were obtained by standard density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll (BD Bioscience, San Jose CA), resuspended in 10% DMSO/FBS, frozen using Mr. Frosty Freezing Containers (Thermo Fisher, Waltham MA), and stored in liquid nitrogen until analysis. Frozen UCBMCs were thawed and UCB monocytes were purified using CD14 antibodies conjugated to magnetic microbeads per manufacturer’s recommendations (Miltenyi Biotech, San Diego CA). Magnetically bound UCB monocytes were washed and eluted for collection. Positive selection of UCB monocytes was chosen to ensure high purity of the population, which was assessed using flow cytometry and was ≥90% for all samples analyzed.

LPS Stimulation and detection of soluble mediators

Purified UCB monocytes were plated at 2×105/well and stimulated with 100ng (1 ug/mL) of LPS (TLR4 ligand, E. coli 055:B5; InvivoGen, San Diego CA) or left untreated for 16 hours at 37C and 5% CO2. The above concentration of LPS was previously standardized for robust detection of gene expression in primary human monocytes (22, 23). Following the 16hr incubation, cells were spun down. Supernatants were collected for analysis using the human ProcartaPlex multiplex immunoassay (eBioscience/Affymetrix), which simultaneously measures the concentration of 45 cytokines (TNFα, TNFβ, IFNG, IL1α, IL1β, IL6, IL13, IL15, IL18, IL22, IL23, and IL27, IL1RA, IL4, and IL10), chemokines (MIP1α, MIP1β, MCP-1, IL8, IP10, RANTES, and Eotaxin), and growth factors (VEGF, SDF1α, EGF, PDGF, GMCSF, HGF, and FGF2) (http://www.ebioscience.com/human-cytokine-chemokine-growth-factor-1-45-plex-procartaplex-multiplex-kit.htm). Values below the limit of detection were designated as half of the lowest limit.

Principal component analysis of cytokine, chemokine, and growth factors was performed using prcomp function and visualized using ggbiplot package in R. Differences between protein levels between the two groups before and after stimulation were statistically assessed using two-way ANOVA and corrected for multiple comparisons using Sidak’s multiple comparison test. Differences in protein levels following stimulation after corrections for resting levels was statistically assessed using unpaired t-test (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Cell Migration Assay

Migratory potential of PBMCs was measured using CytoSelect 96-well Cell Migration Assay Cell Migration assay (Cell Biolabs, San Diego CA). Briefly, 2×105 adult PBMCs were incubated in serum free media in the upper wells of the migration plate, while supernatants collected following LPS stimulation of UCB monocytes were placed in lower wells. Migration plates were incubated at 37C and 5% CO2 for 5hr. The number of cells that migrated into the lower wells was quantified using CyQuant cell proliferation assay per manufacturer’s instructions. Absolute numbers of migrated cells were calculated using a standard curve for CyQuant assay with a linear range of fluorescence limited from 50 to 50,000 cells. Supernatant from LPS stimulated purified adult monocytes (n=2) was used as a positive control, whereas media served as negative control.

RNA-Seq

RNA from stimulated and unstimulated monocyte cell pellets were extracted using Zymo Research Direct-zol RNA mini-prep (Zymo Research, San Diego CA) per manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and integrity was determined using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Following ribosomal RNA depletion using Ribo-Gone rRNA removal kit (Clontech, Mountain View CA), libraries were constructed using SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq kit (Clontech, Mountain View CA). Briefly, rRNA-depleted RNA was fragmented, converted to ds cDNA and ligated to adapters. The roughly 300 bp long fragments were then amplified by PCR and selected by size exclusion. Each library was prepared with unique index facilitating multiplexing of several samples for sequencing. Following QC for size, quality and concentrations, libraries were multiplexed and sequenced to single-end 100-bp sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq2500 platform.

RNA-Seq Bioinformatics

Raw reads assessed for quality using FASTQC (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) and trimmed using TrimGalore (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). To conform to Clontech library prep protocol, five bases from leading end and 3 bases at the trailing end were trimmed, with minimum base quality of 30 ensuring reads of a minimum length of 50 bases. Reads were then aligned to the human genome using TopHat2 (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml). Reads mapping uniquely to exonic regions were counted gene-wise using GenomicRanges package in R. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were determined using edgeR (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html) and defined as those with fold-change ≥2 and an FDR corrected p value of ≤0.05. Functional enrichment of DEGs and pathway over-representation was performed using InnateDB (http://www.innatedb.com/redirect.do?go=batchGo) and confirmed independently using DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/summary.jsp). Transcriptional regulation of DEGs was performed using cisRed (http://www.cisred.org/). All plots were generated in R using gplots. Gene networks were generated using MetacoreTM (Thomson Reuter, Washington, DC).

Methyl-Seq

DNA cytosine methylation levels in purified resting UCB monocytes were measured at single base resolution using a targeted bisulfite sequencing approach (SureSelectXT Human Methyl-Seq enrichment system, Agilent, Santa Clara CA), focusing on regions where methylation is known to impact gene regulation (cancer tissue-specific differentially methylated regions or DMRs, GENCODE promoters, CpG islands, shores and shelves ±4kb, DNase I hypersensitive sites and RefGenes). Restricting methylation measurements to a relevant portion of the genome increases the statistical power for detecting subtle alterations in gene regulatory regions. Briefly, 200 ng genomic DNA was isolated from resting 2–5×105 CD14+ monocytes using Quick-gDNA MiniPrep (Zymo Research, Irvine CA), sheared to 100–200 bp using Covaris Ultrasonicator (Covaris, Woburn MA) and verified using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. The ends of sheared DNA were repaired, 3′ adenylated, and ligated with methylated adapters. These DNA fragments were then hybridized with 120 nt biotinylated RNA library fragments that recognize methylated DNA regions and isolated using streptavidin beads followed by bisulfite conversion using Zymo EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo, Irvine CA), which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils. Libraries were then PCR amplified, ligated with unique indices, and sequenced on Illumina NextSeq500 platform to generate 60 million 50 bp paired-end reads per sample. Efficiency of bisulfite conversion was measured using 20 pg of unmethylated phage lambda DNA spiked in with each sample before DNA fragmentation. The bisulfite non-conversion rate was calculated as the percentage of cytosines sequenced at cytosine reference positions in lambda genome. Six lean and 3 obese samples were used in these experiments, and among them 3 lean and 3 obese samples were also included in the stimulation studies allowing us to carry out a pairwise correlation analysis between gene expression and DNA methylation patterns.

Methyl-Seq Bioinformatics

Raw reads were assessed for quality and trimmed to ensure bases with quality scores less than 30 and reads shorter than 50 bases were eliminated. QC passed reads were aligned to the human genome hg19 using Bismark (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/bismark/). To measure bisulfite conversion rates, reads were mapped to phage lambda genome that was spiked into each library. PCR duplicates in the alignment files were filtered using picard tools (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) and file conversions were performed using samtools (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/). Single base resolution methylation calls were made using the R package methylKit (https://github.com/al2na/methylKit). Differences in methylation between lean and obese groups was measured using a logistic regression model built in methylKit, allowing us to identify differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) with at least 25% difference in methylation levels and an FDR corrected p-value of at least 0.05. DMCs overlapping chromosomes X, Y and mitochondrial genome were eliminated from subsequent analyses. We performed optimized region analysis of methylation using eDMR (https://github.com/ShengLi/edmr), which uses a bimodal distribution to identify accurate boundaries of regions/loci harboring significant epigenetic changes without a priori assignment of DMR length. DMC and DMR locations were annotated using HOMER (http://homer.salk.edu). DMRs overlapping genic and intergenic regions were enriched using InnateDB, DAVID, and GREAT (http://bejerano.stanford.edu/great/public/html/).

Correlation between DNA methylation and gene expression

For context-specific association between DNA methylation changes and gene expression, we first compared DMR annotations with gene expression changes between stimulated cells from both groups after correcting basal transcription levels in resting cells. For each DMR, the methylation difference scores were considered. For the expression of genes associated with the genomic context, the fold change in obese group relative to the lean group following stimulation was considered after correcting the transcriptional levels in corresponding unstimulated cells. Only DEGs with FDR ≤ 10% were considered.

We then used a second approach for genome-wide correlations between methylation and gene expression. Using an extension of the established statistical framework, sample specific correlations were evaluated (24) using 3 lean and 3 obese samples for which both RNAseq and methylSeq data were available. Briefly, for each gene, association regions were extended 5KB upstream of transcription start site (TSS) and 5KB downstream of transcription termination site (TTS) with the RPKM of the gene assigned as the expression value for the sample (Supplement Figure 4). For methylation scores, we considered only cytosines with measured values across all samples. Median beta levels within each region for a sample were assigned as the methylation level for the particular sample. Beta values were measured taking into consideration differing coverage at different genomic locations allowing us to perform a weighted correlation analysis. Next, for each gene, sample wise weighted correlation between beta values and RPKM was performed using rcorr function from Hmisc package (http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/wiki/Main/Hmisc) in R, and corrected for multiple hypothesis testing generating false discovery rates for each association.

RESULTS

UCB monocytes from babies born to obese mothers respond poorly to LPS

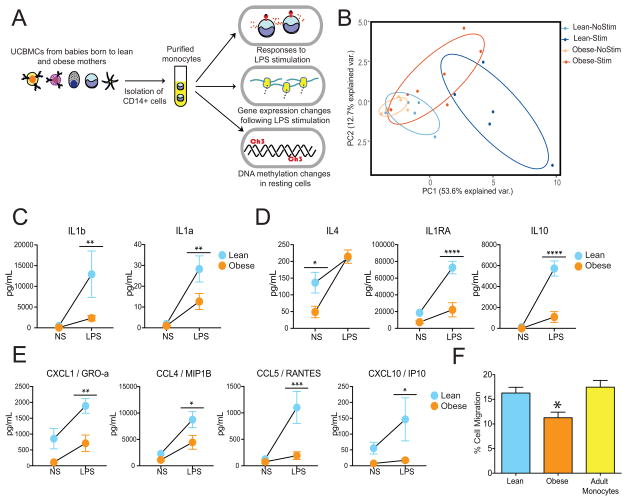

Our previous studies showed a reduced ability of monocytes from babies born to obese mothers to respond to LPS (TLR4 agonist) as well as HKLM/Pam3CSK (TLR1/2 ligands) (19). However, these experiments were carried out using total umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells (UCBMC) and only measured intracellular levels of TNFα and IL6. To specifically assess the impact of pregravid BMI on the functional ability of UCB monocytes to respond to the TLR4 ligand LPS, CD14+ monocytes were purified from UCBMC collected from babies born to lean (lean group) and obese (obese group) mothers, then cultured overnight in the presence or absence of LPS (Figure 1A). Production of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors was determined in the supernatant using a human multiplex immunoassay. Principal component analysis (PCA) clearly indicates that while unstimulated and stimulated UCB monocytes isolated from the lean group formed distinct immune mediator production profiles, those from the obese group had overlapping profiles indicative of the lack of response to LPS (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. UCB monocytes from babies born to obese mothers (obese group) generate dampened responses following ex vivo LPS stimulation.

(A) Experimental design interrogating the influence of maternal pregravid obesity on transcriptional, epigenetic and functional responses of cord blood monocytes (B) Principal Component Analysis of immune mediators released by monocytes from lean and obese groups in the absence and presence of LPS as measured by multiplexed ELISA assay. (C – E) Secreted levels of (C) pro-inflammatory mediators, (D) regulatory cytokines and (E) chemokines following LPS stimulation. (F) Bar graphs representing migration of adult PBMC towards the media of LPS stimulated UCB monocytes from lean and obese groups.

In particular, we observed dampened responses across several mediators secreted following LPS stimulation including pro-inflammatory mediators IL1α and IL1β (Figure 1C), anti-inflammatory cytokines IL10 and IL1RA (Figure 1D), and chemokines CCL4, CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL10 (Figure 1E). Except IL4, we observed no differences in analyte levels produced by resting cells from both groups (Figure 1D). These differences in the levels of secreted immune mediators was observed in the absence of any variations in the frequencies of either total or CD16+ UCB monocytes from the lean or obese group (19). Moreover, expression of cell surface receptors CD14, CD16, and TLR4 was comparable between lean and obese groups (Supplement Figure 1A). In order to determine whether the reduced production of soluble mediators by UCB monocytes from the obese group was functionally relevant, we measured the ability of adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to migrate in response to the supernatant collected from LPS stimulated UCB monocytes from lean and obese groups. In line with the reduced concentration of several chemokines, we detected a significant reduction in the ability of adult PBMCs to migrate in response to the LPS-supernatant from the obese group compared to the lean group (Figure 1F).

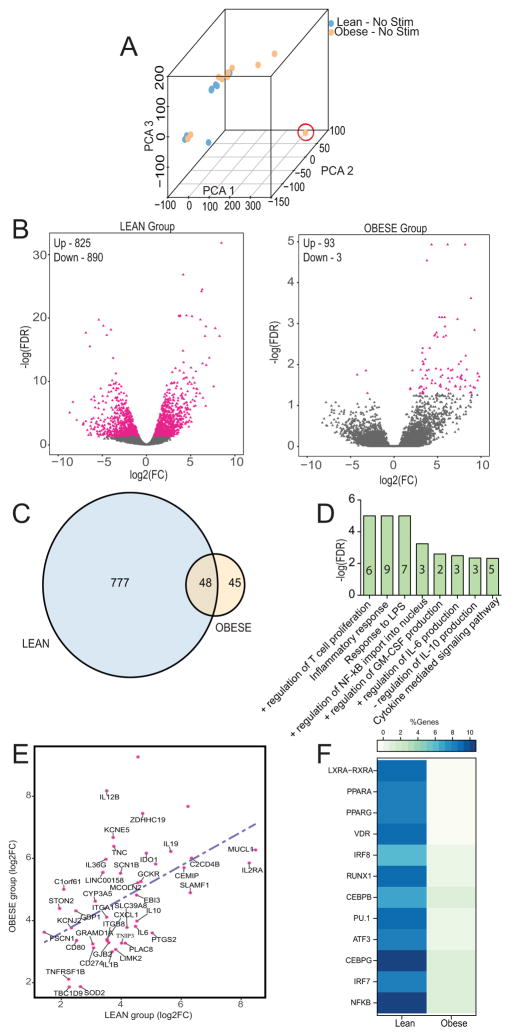

UCB monocytes from lean and obese groups are transcriptionally distinct following LPS stimulation

We next investigated if the dampened response of neonatal monocytes from the obese group stems from reduced transcriptional activation following LPS stimulation using RNA-Seq (Figure 1A). As described for soluble mediators above, the transcriptional profiles looked indistinguishable prior to LPS stimulation (Figure 2A and Supplement Figure 1B). However, despite comparable surface and gene expression of TLR4 (Supplement Figure 1A and 1C), large gene expression changes were only observed in the lean (Figure 2B and Supplement Figure 1D) but not the obese group (Figure 2B and Supplement Figure 1E) following LPS stimulation. More specifically, while 825 up-regulated and 890 down-regulated genes were identified in UCB monocytes from lean group following LPS stimulation (FDR ≤ 5%, |Fold Change| ≥ 2) (Figure 2B), monocytes from the obese group show very limited gene expression changes following stimulation (93 up- and 3 down-regulated) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. LPS stimulation induces a blunted transcriptional response in UCB monocytes from the obese group.

(A) Principal Component Analysis of transcriptional profiles of unstimulated UCB monocytes from lean and obese group. Sample circled in red (obese group) was identified as an outlier and removed from subsequent analysis. (B) Volcano plots representing overall gene expression changes observed in lean (left) and obese (right) group following LPS stimulation. Genes displaying statistically significant differences in expression following LPS stimulation compared to resting state are marked in pink. The numbers of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that are either upregulated (Up) or downregulated (Down) are indicated. (C) Venn diagram identifying overlap of up-regulated DEGs in lean and obese groups following LPS stimulation. (D) Functional enrichment (Biological processes) of the 48 DEGs upregulated in both obese and lean groups carried out using InnateDB. Numbers within the bars indicate the number of genes that mapped to the gene ontology (GO) term. (E) Scatterplot of fold changes and regression line based on best-fit of the 48 DEGs upregulated in both groups revealed lower magnitudes of up-regulation in the obese group. (F) Heatmap of the percentages of genes regulated by LPS inducible and metabolically sensitive transcription factors (TFs) in lean and obese groups. The percentages were calculated based on total number of predicted genes regulated by each TF as determined by cisRed.

Only 48 genes were up-regulated in both lean and obese groups in response to LPS, with 777 and 45 genes up-regulated exclusively in the lean and obese groups respectively (Figure 2C). The 48 shared differentially expressed genes (DEGs) enriched to pathways associated with LPS response (Figure 2D) and comprised genes important for the inflammatory response including cytokines and chemokines (IL1B, IL6, IL2RA, IL10, and CXCL1), regulators of T-cell activation (CD80, CD274, and SLAMF1), and cell adhesion (MUCL1, LIMK2, and ITGB8) (Figure 2D). However, the magnitudes of fold change of these shared up-regulated genes was lower in the obese group compared to the lean group (Figure 2E). Additionally, expression of TNFRSF1, the major receptor for TNFA in myeloid cells and TNIP3, a negative regulator of NF-kB induced gene expression program, was reduced in the obese group (Figure 2E). Similar trends were also observed in expression of classic stress responders such as mitochondrial encoded SOD2 and zinc transporter SLC39A8 (Figure 2E). These observations suggest an overall suppression of the LPS-induced transcriptional program in UCB monocytes from the obese group. Not surprisingly, the number of genes trans-activated by transcription factors (TFs) regulated by the metabolic status of monocytes (LXRA/RXRA, PPARA, PPARG, and VDR) was dramatically reduced in the obese group (Figure 2F).

UCB monocytes from the obese group fail to transcriptionally activate and suppress key regulatory processes involved in cellular response to LPS

Functional enrichment of the 777 genes up-regulated exclusively in UCB monocytes from the lean group following LPS stimulation revealed significant over representation of inflammatory innate immune processes, such as “JUN kinase activity” and “MyD88-dependent TLR signaling pathway” (Figure 3A). Some of the notable DEGs within these processes include genes involved in toll-like receptor engagement (TLR1, TLR2, TLR8, PTX3, TNIP1, and ACOD1), pro-inflammatory responses (TNF, IL1A, IL15, TNFAIP, and IRGM), cell migration (CCR7, CCL20, CCL19, CXCL3, and CXCL8), and pathogen pattern recognition (FPR2, NOD1, TLRs 1, 2, and 8) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. UCB monocytes from lean group display a robust LPS inducible inflammatory transcriptional program.

(A) Functional enrichment of the 777 genes upregulated exclusively in the lean group carried out using InnateDB. Numbers within the bars indicate the number of genes that mapped to each of the GO terms. (B) Heatmap displaying expression levels (RPKM) of the 31 genes that mapped to the GO term “inflammatory response”. (C) Functional enrichment of 890 genes down-regulated only in lean group following LPS stimulation as reported by InnateDB. Numbers within the bars indicate the number of DEGs that mapped to each of the GO terms. (D) Heatmap of immune related genes down-regulated exclusively in the lean group.

Some of the 45 genes up-regulated exclusively in UCB monocytes from the obese group played a role in signaling (CACNA1F, MECOM, PPP2R2C, and CSF2) and metabolism (EPHX2, NUBP2, and CHRM3) (Table I). Notable genes within this group include FLI1, a negative regulator of matrix metalloproteases and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 (25), and the long non-coding RNA oncogene LINC00511, which plays a role in chromatin remodeling (26) (Table I).

Table I.

Genes exclusively up-regulated by LPS in obese group1

| Gene ID | Fold Change | Gene Symbol | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENSG00000166069 | 12.27 | TMCO5A | Transmembrane and coiled-coil membrane 5A |

| ENSG00000273478 | 11.06 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000184156 | 10.31 | KCNQ3 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily Q member 3 |

| ENSG00000241106 | 10.25 | HLA-DOB | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DO beta |

| ENSG00000257931 | 10.23 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000215871 | 10.12 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000138028 | 10.03 | CGREF1 | Cell growth regulator with EF-hand domain 1 |

| ENSG00000222036 | 9.79 | POTEM | POTE ankyrin domain family member M |

| ENSG00000213344 | 9.63 | PCNPP3 | PEST containing nuclear protein pseudogene 3 |

| ENSG00000250658 | 9.61 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000224607 | 9.61 | IGKV1D-27 | Immunoglobulin kappa variable 1D-27 (pseudogene) |

| ENSG00000234320 | 9.30 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000144452 | 9.15 | ABCA12 | ATP binding cassette subfamily A member 12 |

| ENSG00000234335 | 8.87 | RPS4XP11 | Ribosomal protein S4X pseudogene 11 |

| ENSG00000164400 | 8.85 | CSF2 | Colony stimulating factor 2 |

| ENSG00000198307 | 8.78 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000227107 | 8.76 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000123243 | 8.24 | ITIH5 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain family member 5 |

| ENSG00000203721 | 8.19 | LINC00862 | Long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 862 |

| ENSG00000102001 | 8.18 | CACNA1F | Calcium voltage-gated channel subunit alpha1 F |

| ENSG00000266664 | 7.78 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000112742 | 7.77 | TTK | TTK protein kinase |

| ENSG00000259315 | 7.69 | ACTG1P17 | Actin gamma 1 pseudogene 17 |

| ENSG00000157429 | 7.64 | ZNF19 | Zinc finger protein 19 |

| ENSG00000268355 | 7.63 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000150672 | 7.59 | DLG2 | Discs large MAGUK scaffold protein 2 |

| ENSG00000065618 | 7.30 | COL17A1 | Collagen type XVII alpha 1 |

| ENSG00000171811 | 7.29 | CFAP46 | Cilia and flagella associated protein 46 |

| ENSG00000227036 | 7.08 | LINC00511 | Long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 511 |

| ENSG00000229727 | 7.06 | N/A | Uncharacterized |

| ENSG00000163121 | 7.05 | NEURL3 | Neuralized E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 3 |

| ENSG00000185834 | 6.72 | RPL12P4 | Ribosomal protein L12 pseudogene 4 |

| ENSG00000224424 | 6.52 | PRKAR2A-AS1 | PRKAR2A antisense RNA 1 |

| ENSG00000120915 | 6.22 | EPHX2 | epoxide hydrolase 2 |

| ENSG00000085276 | 5.38 | MECOM | MDS1 and EVI1 complex locus |

| ENSG00000147130 | 5.37 | ZMYM3 | Zinc finger MYM-type containing 3 |

| ENSG00000133019 | 5.36 | CHRM3 | Cholinergic receptor muscarinic 3 |

| ENSG00000074211 | 5.33 | PPP2R2C | Protein phosphatase 2 regulatory subunit B gamma |

| ENSG00000100726 | 4.74 | TELO2 | Telomere maintenance 2 |

| ENSG00000239899 | 4.74 | RN7SL674P | RNA, 7SL, cytoplasmic 674, pseudogene |

| ENSG00000185803 | 4.32 | SLC52A2 | Solute carrier family 52 member 2 |

| ENSG00000171045 | 3.69 | TSNARE1 | T-SNARE domain containing 1 |

| ENSG00000095906 | 3.43 | NUBP2 | Nucleotide binding protein 2 |

| ENSG00000134326 | 3.18 | CMPK2 | Cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase 2 |

| ENSG00000151702 | 2.99 | FLI1 | Fli-1 proto-oncogene, ETS transcription factor |

List of the 45 differentially expressed genes (DEG) up regulated only in UCB monocytes from the obese group following LPS stimulation.

A large number of genes were down-regulated exclusively in UCB monocytes from the lean group. These DEGs enriched to regulatory processes such as mRNA catabolic processes (e.g. L ribosomal proteins), translation initiation, and termination (Figure 3C and Supplement Figure 2A). We also observed down-regulation of genes involved in antigen presentation (HLADMA, HLADPA1, HLADPB1, HLADQA1, HLADQB1, and HLADRA), T-cell co-stimulation (CD4, CD86, PAK1, SPN, ICOSLG, and MAP3K14) (innate immune response, and response to wounding (Figure 3C and 3D). Additionally, network analysis revealed that several of the down-regulated DEGs directly interact with one another and are regulated by key transcription factors AP-1, SMAD3, CREB1, and IRF8 (Supplement Figure 2B).

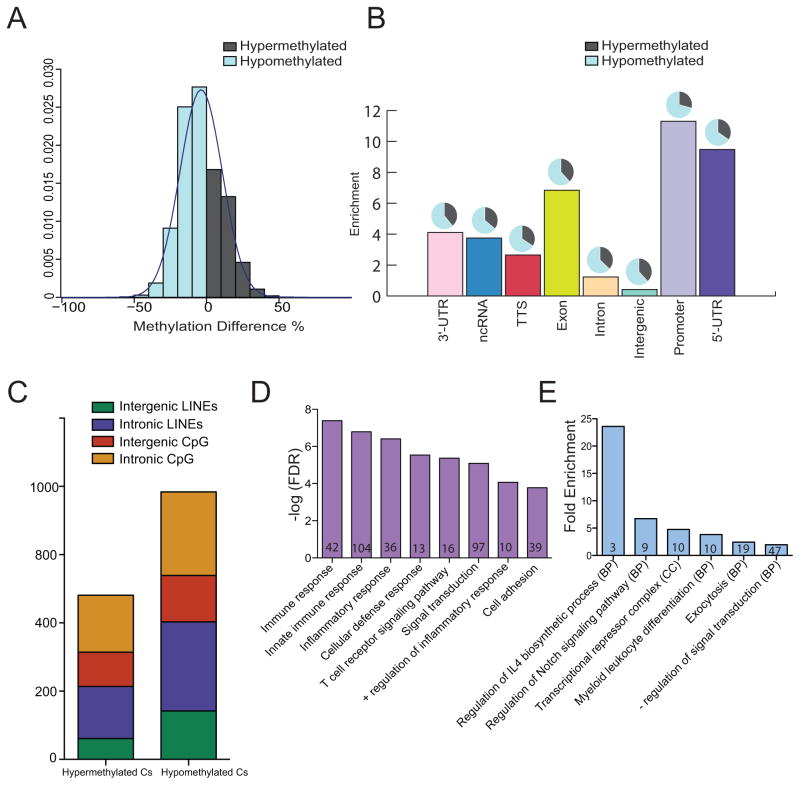

Maternal Obesity is associated with global hypomethylation in UCB monocytes

Given the large functional and transcriptional differences between lean and obese groups, we next wanted to identify epigenetic mechanisms by which maternal obesity dysregulates UCB monocyte response to LPS stimulation. Given previous reports of maternal obesity-associated DNA methylation changes in select loci in offspring PBMC, and its role in predicting cellular responses to biological stimuli like LPS (27), we investigated pregravid obesity-induced changes in methylome of UCB monocytes. We measured global changes in methylation levels of 2,278,000 – 3,392,222 cytosines at single nucleotide resolution, using a targeted approach. After filtering methylation changes that weren’t measured across all samples and those located on X and Y-chromosomes, a total of 1,769,148 differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) were included in our analysis. Overall, maternal obesity was associated with more hypomethylation (8,887 cytosines, Δβ ≥ 25%, q ≤ 0.05) than hypermethylation (4,838 cytosines, Δβ ≤ 25%, q ≤ 0.05) in UCB monocytes (Figure 4A and Supplement Figure 3A). These trends were consistent across all genomic contexts (Figure 4B) and were uniformly distributed across all chromosomes (Supplement Figure 3B). Methylation changes were more pronounced in 5′ regulatory and promoter regions (Figure 4B). The global trends in methylation changes agree with methylation patterns in long interspersed nuclear elements (LINE), which have been previously reported as a bona fide measure of methylation levels in the genome (Figure 4C) (28).

Figure 4. Maternal pregravid obesity is associated with global hypomethylation in UCB monocytes as measured by targeted bisulfite sequencing.

(A) Distribution of overall single base resolution methylation changes in UCB monocytes from obese group relative to lean group. (B) Bar graph representing context specific changes in methylation following correction for lengths of genomic regions indicates particular enrichment at the 5′ regulatory and promoter regions. The pie charts above each bar represent the proportion of raw number of hypo- and hyper-methylated cytosines in each context after including corrections for genomic lengths. (C) Profile of frequencies of differentially methylated cytosines (DMCs) overlapping LINE and CpG islands. (D) Genes with DMCs in 5′ regulatory regions preferentially enrich to immune system processes. Numbers within the bars indicate the number of genes that mapped to the GO term. (E) Functional enrichment of genes regulated by DMCs in CpG islands using cis-regulatory model described by GREAT shows over-representation of inflammatory processes. Numbers within the bars indicate the number of genes that mapped to the GO term.

Functional enrichment of genes differentially methylated in 5′ regulatory and promoter regions using DAVID revealed over-representation of gene ontology (GO) terms such as immune response (HLAG, CCR3, CCR6, CCR9, NCR2, ITK, and LSP1) and inflammatory response (NFKB1, NFKBIZ, NLRC4, S100A12, IL37, IL23A, IL36G, CLEC7A, CXCR6, and CXCL10) (Figure 4D). Moreover, differential methylation of cytosines within CpG islands was associated with genes involved in regulating IL4 synthesis (ICOSLG, IRF4, and ZFPM1), myeloid cell differentiation (CBFA2T3, FAM20C, NFATC1, and ZFPM1), and transcriptional repression (HDAC4, NCOR2, PRDM16, CTBP2, and ZFPM1) as determined using GREAT (Figure 4E).

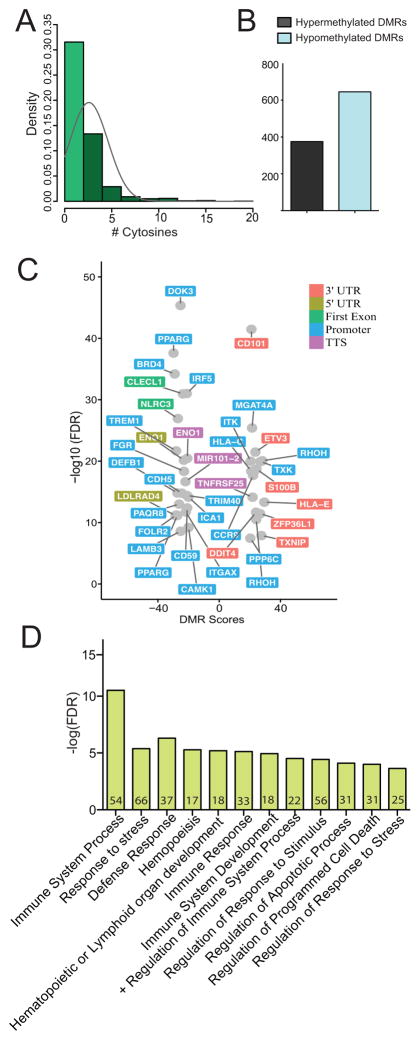

Maternal Obesity induces DNA methylation changes in genomic regions that regulate expression of key immune genes in UCB monocytes

Having established the general pattern of methylation changes in promoter regions, we next asked if resolution of these DMCs into differentially methylated regions (DMRs) would allow us to identify changes in specific genes with higher confidence and biological relevance. Without a priori assignment of region lengths, eDMR (https://github.com/ShengLi/edmr) identified 1506 DMRs with 1020 DMRs containing at least 2 DMCs (Figure 5A): 375 hypermethylated (Δβ ≥ 20%, q ≤ 0.05) and 645 hypomethylated (Δβ ≤ 20%, q ≤ 0.05) DMRs (Figure 5B). While the lengths of these regions were highly variable (Supplement Figure 3C), trends of over-representation in 5′ regulatory regions were maintained in both hypomethylated and hypermethylated DMRs (Supplement Figure 3D). Importantly, our analysis revealed hypomethylation in promoters and 5′ regulatory regions of genes involved in metabolism (CAMK1, PPARG, PAQR8, FOLR2, LDLRAD4, ENO1, and ICA1) (Figure 5C). Additionally, some DMRs overlapped genes important in cell migration and adhesion in myeloid cells (FGR, ITGAX, CDH5, and LAMB3), and defense response (DOK3, TRIM40, TREM1, CD59, IRF5, and DEFB1) (Figure 5C). Finally, we report hypomethylated DMRs overlapping first exons of CLECL1 and NLRC3, two genes critical for the ability of innate cells to activate T cells (Figure 5C). We observed very limited hypermethylation overlapping metabolic genes (RHOH, MGAT4A), but large hypermethylated changes occurring at 3′ and promoter regions of immune genes (CD101, ETV3, S100B, HLAE, HLAC, ITK, RHOH, ZFP36L1, and TNFRSF25), and stress response genes (TXNIP and DDIT4).

Figure 5. Pregravid obesity-associated changes in methylation in UCB monocytes overlap genes critical in metabolism, cell adhesion, and migration.

(A) Distribution of number of cytosines residing in differentially methylated regions (DMRs) determined by eDMR. (B) Bar graph representing the number of hyper- and hypo-methylated DMRs. (C) Volcano plot of immune genes with DMRs overlapping 3′ and 5′ regulatory regions. (D) Functional enrichment of cis-regulatory associations of intergenic DMRs as predicted by GREAT indicates impact on immune system response, development, and apoptosis.

Intergenic DNA methylation changes overlap cis elements regulating defense response and immune development

Since a large number of DMRs overlapped intergenic regions (Supplement Figure 3D), we asked if these changes overlap cis regulatory regions with possible associations with coding regions. We addressed this question using GREAT, with a proximal regulatory assignment of 5 kb upstream and 1kb downstream of transcriptional start sites (TSS), and a distal regulatory assignment of 100 kb on either side of TSS. This analysis revealed significant methylation changes in intergenic regions regulating defense response (HLA-DRA, HLA-DRB5, IFNAR1, IFNGR2, IRF2, CD180, and CXCL1), hematopoietic development (KLF4, CD28, CEBPA, VEGFA, and EPHA2) and apoptosis (BCL6, KDM2B, PSMA6, FLT4, DAD1, and ERCC3) (Figure 5D).

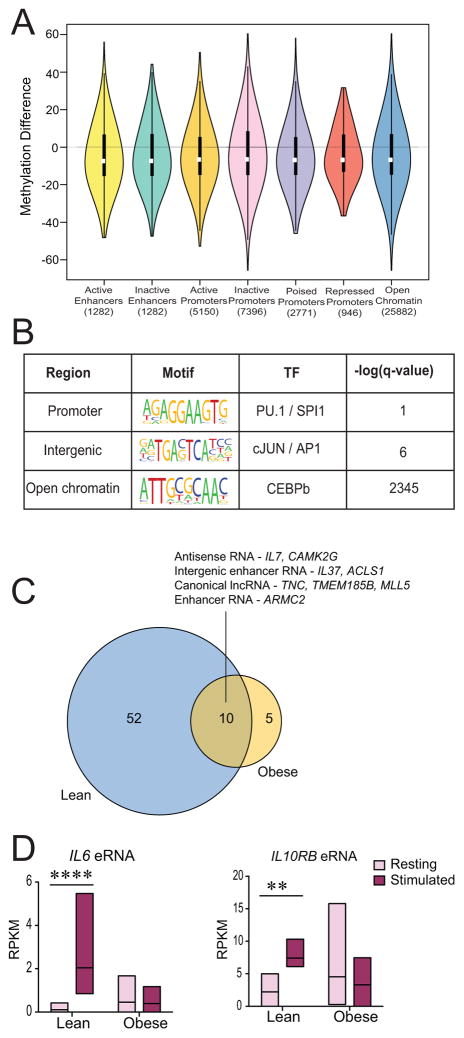

Given recent reports of potential cross talk between DNA methylation and histone methylation in transcriptional silencing of genes during endotoxin tolerance of in vitro cultured monocytes (29), we compared maternal obesity associated DMRs to histone data available from Human ENCODE and BLUEPRINT consortia for CD14+CD16- monocytes (http://epigenomesportal.ca/ihec/) since the overwhelming majority of UCB monocytes are CD16- (19). This analysis showed that DMRs with large magnitudes of methylation differences (both hyper- and hypomethylation) overlapped inactive promoters and open chromatin (Figure 6A). Since DNA methylation has been previously shown to modulate TF occupancy in a context specific fashion (30), we explored preferential TF binding sites in different contexts of DMRs. Promoter DMRs had preferential binding sites for PU.1/SP1 transcription factor, while intergenic DMRs had preferential cJun/AP1 binding sites, and open chromatin regions had increased CEBPB binding sites (Figure 6B). Importantly, all of these transcription factors are critical for the LPS inducible transcriptional program in monocytes and macrophages (31). In comparison, we observed modest changes in both active and inactive enhancers (Figure 6A). We next determined whether these modest changes in inducible enhancer regions could affect levels of LPS inducible enhancer RNAs following stimulation. Therefore, we measured expression changes of 257 long noncoding and enhancer RNA (eRNA) previously reported in human THP1 cells following a 4-hour LPS stimulation (32). This analysis revealed dampened expression of LPS inducible enhancers (Figure 6C), including IL6 and IL10RB eRNA (Figure 6D) in UCB monocytes from the obese group, supporting the general theme of dampened transcriptional activation in these cells.

Figure 6. Pregravid obesity-associated DMRs within intergenic regions are more prevalent in inactive promoters.

(A) Violin plots describing methylation changes in DMRs overlapping known monocyte promoter and enhancer profiles predicted by ENSEMBL’s Regulatory Segmentation tool. The violins represent symmetric distribution of methylation differences in each region, with violin height representing the range of methylation difference. Inactive promoters and open chromatin regions displayed the broadest range of changes. (B) Enriched motifs for DMRs overlapping different genomic contexts predicted by HOMER. (C) Venn diagram of statistically significant enhancer and long non-coding RNA differentially expressed following LPS stimulation in lean and obese groups. (D) Pre- and post-stimulation levels of IL6 and IL10RB enhancer RNAs in lean and obese groups indicate significant changes in the lean group only.

High pregravid maternal BMI-associated DNA methylation patterns correlate with altered gene expression in UCB monocytes

Next, we integrated the expression and methylation datasets to identify correlations between maternal pregravid obesity-induced DNA methylation changes in resting UCB monocytes and corresponding gene expression changes following LPS stimulation. We used two approaches to address this question. Our first method measured gene expression differences between stimulated monocytes from both groups after correcting for expression levels in resting cells and compared it with methylation changes in those genes in a context specific manner. This analysis revealed that only 30 DMRs overlapped gene bodies with significant gene expression changes (Table II). Some of these genes included: ADA (Adenosine deaminase), which plays a critical role in monocyte/macrophage maturation (33); ZFP36L1 (Zinc Finger Protein Like 1), critical for monocyte/macrophage differentiation (34); and KLF2 (FC=2.87), which regulates proinflammatory activation of monocytes (35). Additionally, this list included two TLR4 interacting genes: CD180, a TLR4 accessory protein that negatively regulates TLR4 signaling (36), and LY86, which cooperates with TLR4 and CD180 to mediate the response to LPS (37) (Table II). This approach, however, compares overall changes in methylation with gene expression and is unable to capture subtle differences in sample specific methylation and gene expression.

Table II.

Direct context specific association between gene expression and DNA methylation1

| 3′ Regulatory Region | Methylation Difference | Expression Fold Change |

| ADA | 25.58 | 2.29 |

| FAN46A | −29.05 | −2.49 |

| TCF7L1 | −23.81 | 4.58 |

| ZFP36L1 | 26.74 | −1.79 |

| 5′ Regulatory Region | Methylation Difference | Expression Fold Change |

| ANKRD22 | −29.07 | 5.17 |

| APMAP | −25.09 | −2.09 |

| CECR2 | −21.25 | −2.67 |

| FAM65B | 25.26 | 1.76 |

| MIR3945HG | −27.06 | 3.57 |

| PDCD1LG2 | −35.49 | 3.05 |

| TMEM177 | 21.52 | 3.79 |

| UBASH3B | −25.14 | −1.75 |

| ZNF385A | −25.55 | −2.32 |

| Introns | Methylation Difference | Expression Fold Change |

| BHLHE40-AS1 | −22.77 | 7.74 |

| CD180 | −26.39 | −2.86 |

| FOXN3 | −24.01 | −1.63 |

| GPR157 | −28.74 | −2.53 |

| KIAA0930 | −21.57 | −2.30 |

| KIAA0930 | −21.93 | −2.30 |

| LINC00862 | −30.47 | 7.95 |

| LY86 | 21.61 | −3.37 |

| MAFA | 22.25 | 3.05 |

| MEGF6 | −25.46 | 3.05 |

| MEIKIN | 24.45 | −3.47 |

| RAPGRP1 | 24.46 | 2.17 |

| RGS2 | −21.81 | −2.92 |

| RPS6KA2 | −26.85 | −2.91 |

| SH3PXD2B | −29.64 | 2.34 |

| SLC25A37 | −24.23 | 2.33 |

| SORT1 | −24.42 | −2.43 |

| TBC1D1 | −22.87 | 2.80 |

| TIMM13 | −31.52 | −2.15 |

| Exons | Methylation Difference | Expression Fold Change |

| AKR1A1 | −23.10 | −2.10 |

| CMYA5 | 24.93 | 4.85 |

| FAM46A | −29.05 | −2.49 |

| FAM78A | −30.60 | −1.89 |

| GBP5 | −23.07 | 2.56 |

| KLF2 | 23.66 | 2.87 |

| LGALS12 | −21.56 | −4.23 |

| SNORD17 | −22.49 | 2.977 |

| TCF7L1 | −23.81 | 4.58 |

| ZFP36L1 | 26.74 | −1.79 |

| ZFP36L1 | 23.12 | −1.79 |

Summary of direct context specific changes in genes with statistically significant expression and methylation changes. Gene names in column have been categorized by specific contexts in which methylation changes were observed. Columns two and three represent changes in methylation and gene expression respectively.

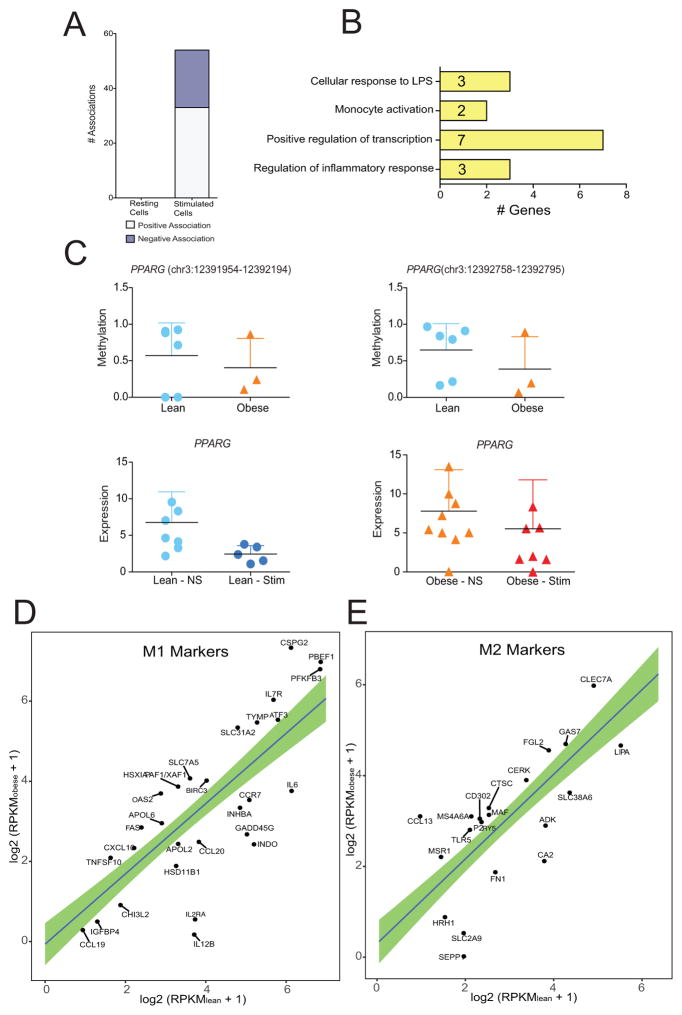

We therefore, used a second; more robust and sensitive method to measure sample-wise association between DNA methylation levels and gene expression levels, allowing us to measure association before and after stimulation separately (Supplement Figure 4). This approach not only accounts for contributions of intergenic DNA methylation changes, but also captures heterogeneity in methylation and expression changes among individual samples before and after LPS stimulation. This approach revealed no statistically significant associations in unstimulated cells, but 54 positive and negative associations were detected in post LPS stimulation expression profiles suggesting that maternal obesity associated DNA methylation changes are more predictive of gene expression changes following ex vivo stimulation, as previously reported in adult PBMCs (27) (Table III) (Figure 7A).

Table III.

Weighted Pairwise association between gene expression and DNA methylation1

| Gene | Chr | Start | Stop | Spearman |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBNO2 | chr19 | 1102569 | 1102675 | 1 |

| SBNO2 | chr19 | 1177517 | 1177605 | 1 |

| PPARG | chr3 | 12392758 | 12392795 | 1 |

| ARHGAP26 | chr5 | 142431271 | 142431331 | 1 |

| ZNF516 | chr18 | 74201176 | 74201349 | −1 |

| AC007278.3 | chr2 | 103052681 | 103052768 | −1 |

| PTRH1 | chr9 | 130474243 | 130474298 | −1 |

| IRF5 | chr7 | 128579512 | 128580582 | 1 |

| NFATC1 | chr18 | 77269145 | 77269329 | −1 |

| IGF2BP2 | chr3 | 185429286 | 185429418 | 1 |

| MIR3945 | chr4 | 185776752 | 185776854 | 1 |

| PPARG | chr3 | 12391954 | 12392194 | 1 |

| JAK1 | chr1 | 65363869 | 65363974 | 1 |

| ZNF516 | chr18 | 74198756 | 74198855 | −1 |

| RP5-968J1.1 | chr20 | 1798583 | 1798776 | −1 |

| WDR59 | chr16 | 75034758 | 75034983 | −1 |

| ANKRD13A | chr12 | 110450642 | 110450723 | 1 |

| PIK3R5 | chr17 | 8867288 | 8867387 | −1 |

| CTD-2319I12.1 | chr17 | 58160030 | 58160123 | −1 |

| IL1R1 | chr2 | 102680182 | 102680254 | −1 |

| MOAP1 | chr14 | 93652953 | 93653040 | 1 |

| METTL9 | chr16 | 21663891 | 21663937 | 1 |

| RASA3 | chr13 | 114900020 | 114900137 | −1 |

| UXS1 | chr2 | 106712973 | 106713176 | 1 |

| TIMM13 | chr19 | 2423123 | 2423287 | −1 |

| SEP9 | chr17 | 75385143 | 75385269 | −1 |

| RGCC | chr13 | 42037300 | 42037548 | −1 |

| AC003104.1 | chr17 | 40425651 | 40425728 | 1 |

| TBC1D7 | chr6 | 13303043 | 13303065 | 1 |

| TRAJ20 | chr14 | 22993035 | 22993190 | 1 |

| FOXP1 | chr3 | 71542816 | 71542914 | 1 |

| TRAK1 | chr3 | 42258087 | 42258157 | −1 |

| SNAP23 | chr15 | 42803175 | 42803323 | 1 |

| ERGIC1 | chr5 | 172314050 | 172314166 | −1 |

| MXRA7 | chr17 | 74709515 | 74709775 | 1 |

| RP11-589N15.1 | chr8 | 11754669 | 11755204 | 1 |

| BIN3 | chr8 | 22503551 | 22503623 | 1 |

| AEN | chr15 | 89168304 | 89168351 | 1 |

| GPR97 | chr16 | 57701448 | 57701619 | 1 |

| ZC3H12A | chr1 | 37937355 | 37937438 | −1 |

| ENDOD1 | chr11 | 94841383 | 94841420 | −1 |

| TREM1 | chr6 | 41254310 | 41254471 | 1 |

| ZNF710 | chr15 | 90547691 | 90548203 | 1 |

| STX5 | chr11 | 62573843 | 62574403 | 1 |

| RP11-426C22.5 | chr16 | 29188779 | 29189157 | −1 |

| TRAJ22 | chr14 | 22993035 | 22993190 | 1 |

| ADAM9 | chr8 | 38855985 | 38856736 | 1 |

| MBNL1 | chr3 | 152046667 | 152046751 | −1 |

| PARN | chr16 | 14530501 | 14530619 | 1 |

| SF1 | chr11 | 64539603 | 64539824 | −1 |

| FCGR2C | chr1 | 161574652 | 161575205 | 1 |

| TMEM80 | chr11 | 692948 | 693088 | 1 |

| HSPA7 | chr1 | 161574652 | 161575205 | 1 |

| RP11-25K21.6 | chr1 | 161574652 | 161575205 | 1 |

Summary of genes with significant association between DNA methylation and expression. All associations FDR p value <0.01. Each gene is provided with genomic location for which a significant association with gene expression is reported.

Figure 7. Pregravid obesity -associated alterations in cytosine methylation within resting UCB monocytes are predictive of LPS-inducible transcriptional responses.

(A) Bar graph representing number of significant associations reported by pair-wise weighted integration of DNA methylation and gene expression profiles following corrections for multiple testing. (B) Assignment of biological functions to 54 genes with significant associations between expression profile and methylation status 5KB surrounding gene body. (C) DNA methylation changes within two DMRs overlapping PPARG gene (top). Gene expression changes in lean (left bottom) and obese (right bottom) following stimulation. (D) Scatterplot comparing normalized transcript levels of transcriptional markers of M1 and M2 macrophages in resting cells from lean and obese groups. X and Y-axis represent RPKMs from lean and obese groups respectively. Only genes outside the 95% CI of the regression line are annotated.

Significant associations between gene expression and DNA methylation was detected in several genes that regulate monocyte activation and polarization (Figure 7B). The most striking example of a robust association was the correlation between expression and methylation of PPARG (Figure 7C), a critical metabolically sensitive TF that regulates LPS inducible gene expression. In particular, PPARG promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and regulates uptake of oxidized LDL (38, 39). Negative associations were also significant for NFATC1, a transcription factor that mediates cell differentiation events in response to TNF (40) and ZNF516, a methylation target in myeloid leukemia (41). We also detected a positive association for IRF5, a transcriptional repressor that polarizes macrophages to an inflammatory phenotype and supports a Th1–Th17 response (42) and FOXP1, a transcription factor that regulates monocyte differentiation via its role in integrin engagement (43, 44).

Since we detected significant associations in genes important for monocyte activation and differentiation, we sought to computationally analyze the expression level of genes previously classified as transcriptional markers of M1 and M2 macrophages (45). Since LPS polarizes macrophages to an M1 phenotype, we focused on transcriptional levels of M1 and M2 markers in resting monocytes only. Several cytokine, chemokine, and receptor markers of M1 macrophages (CCL19, IL12B, IL2RA, CCL20, IL6, and CCR7) showed higher expression in UCB monocytes from the lean group compared to monocytes from the obese group. However, these cells had greater expression of apoptotic genes (FAS, XAF1, and BIRC3) and solute carriers (SLC31A2 and SLC7A5) compared to the lean counterparts (Figure 7D). In contrast, M2 cytokine and receptor markers (MSR1, CCL13, CD302, CLEC7A, P2RY5, and MS4A6A) had higher expression in the obese group (Figure 7E), whereas enzymes and solute carriers that mediate M2 phenotype were more up regulated in the lean group. These gene expression profiles strongly suggest that UCB monocytes from the lean group are more poised towards differentiating into an M1 phenotype while those from the obese group are poised towards a regulatory phenotype.

DISCUSSION

In utero exposure to environmental factors can influence cellular developmental processes and long-term health outcomes in the offspring (46). Of particular importance, maternal nutrition serves as a critical early environmental signal that can perturb the gestational milieu to influence metabolic plasticity during fetal development (47, 48). This phenomenon has been demonstrated in animal models of nutritional constraint (48–50), intrauterine growth restriction (51–53), and epidemiological studies (54, 55). Findings from these studies demonstrate that reprogramming of gene expression and rewiring of epigenetic circuitry mediate early alteration of offspring cellular and developmental function. However, although pregravid obesity is widespread and has been linked to several adverse outcomes for both mother and child, the mechanisms remain under-studied. Therefore, in this study, we investigated how the maternal obese environment reprograms the neonatal immune system.

Initial studies from our laboratory demonstrated that UCB monocytes collected form babies born to obese mothers fail to respond vigorously to TLR1/2 and TLR4 ligands (19). TLRs play a critical role in the recognition of pathogens that are relevant to neonates, including ones recognized by TLR2 (group B Streptococcus (56), Listeria monocytogenes, Mycoplasma hominis, (57) C. albicans hyphae, and cytomegalovirus (58)) and TLR4 (Enterobacteriaceae, C. albicans blastoconidia (58), and respiratory syncytial virus (59)). Dysregulated TLR signaling has been attributed to development of several early diseases in neonates such as necrotizing enterocolitis (60). Given that babies born to obese mothers are at increased risk of neonatal infections such as necrotizing enterocolitis and bacterial sepsis (5, 6, 61), we investigated the impact of pregravid obesity on functional, transcriptional and epigenetic profiles of UCB monocytes in response to LPS stimulation.

In agreement with our previous study (19), we report dampened UCB monocyte cytokine and chemokine responses in the obese group following LPS. Furthermore, our data agree with a previous study that documented reduced IL6 and TNFα production in response to LPS by splenocytes isolated from pups born to obese dams fed a high fat WD during gestation (16). Interestingly, we observed reduced IL4 levels in resting cells from obese group. IL4 suppresses LPS-induced production of IL-12 and IL-10 in human peripheral blood monocytes (62) and inhibits adipogenesis by down-regulating expression of PPARG and CEBPA in adipocytes (63). All four of these genes were downregulated in UCB monocytes from the obese group relative to the lean group. Transcriptional analysis using RNA-Seq confirmed the failure of UCB monocytes from the obese group to fully activate LPS-inducible inflammatory gene expression program. Even genes activated by LPS stimulation in both groups showed relatively lower magnitudes of up-regulation in the obese group compared to the lean group. These transcriptional differences were seen despite comparable levels of CD14 and TLR4 expression as well as frequencies of non-classical monocytes (CD14+CD16+) in unstimulated UCB monocytes, suggesting the involvement of transcriptional/post transcriptional regulatory mechanisms.

Several mechanisms can regulate gene expression. Previous studies have shown that maternal pregravid obesity-associated high concentrations of glucose, insulin, and fatty acids, as well as hormones (e.g. insulin and leptin), and inflammatory mediators (e.g IL6 and TNFα) cross the placenta and influence neuroendocrine and brain development (64). These changes are mediated, in part, by epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, that affect pathways including lipid peroxidation and corticosteroid-receptor expression (65). Similarly, previous clinical studies have demonstrated that maternal BMI is associated with hypomethylation of offspring’s peripheral blood cells at genes involved in inflammatory and metabolic pathways that can persist for years (66, 67). However, no studies to date have investigated the relationship between pregravid maternal obesity-induced methylation changes and immune function in the offspring. Moreover, DNA methylation is highly cell specific, and measurements made in heterogeneous populations of cells such as PBMCs do not necessarily allow us to infer contributions of cell subsets. Therefore, we interrogated methylation changes at a single cytosine resolution in UCB monocytes and its association with LPS-induced gene expression changes.

As previously shown in total blood leukocytes (66, 67), our analysis revealed global hypomethylation in UCB monocytes from babies born to obese mothers relative to their lean counterparts. Profiling these changes in intergenic and gene regulatory regions revealed significant over-representation of critical innate immune genes with potential functional relevance to both the metabolic status of neonatal monocytes and its ability to participate in host defense and inflammation. Additional analysis of intergenic regions and regulatory regions showed statistically significant methylation changes in genomic regions critical for monocyte ability to respond to LPS (AP1, CEPBP) and differentiation (PU.1). These transcription factors dictate both early and late transcriptional responses to LPS and mediate cytokine responses and cell differentiation events in monocytes, suggesting that maternal obesity associated changes in DNA methylation levels in UCB monocytes predispose the cells to respond differently following secondary stimulation such as with LPS.

Recent studies in human immune cells have shown that although DNA methylation is stable when cells are presented with acute biological stimulus like LPS (68), it is predictive of ex-vivo stimulation responses of PBMCs (27). We therefore used this rationale to determine if maternal obesity associated methylation changes in resting UCB monocytes was predictive of its transcriptional response to an ex vivo stimulation. As recently described for adult PBMC (27), sample-wise association between transcriptional and methylation levels, suggest that methylation levels of genes in resting cells are more predictive of gene expression patterns following LPS stimulation than in resting UCB monocytes. The association between methylation and post-LPS gene expression profiles also suggest differences in polarization potential of UCB monocytes. Particularly, transcription factors such as PPARG (38, 39), IRF5(42), and FOXP1(44) have established critical roles in regulating the differentiation of monocytes into pro-inflammatory (M1) or regulatory (M2) macrophages. Indeed, transcriptional analysis of resting UCB monocytes indicate higher levels of M1 genes in lean and M2 genes in obese groups suggesting that UCB monocytes from the obese group may be poised towards a regulatory phenotype.

The small number of associations detected suggests that in the context of maternal obesity, DNA methylation is not the sole regulatory mechanism for gene expression. Alternative regulatory mechanisms include histone posttranslational modifications that could result in active chromatin remodeling. Indeed, maternal high-fat diet induced epigenetic changes in inhibitory histone marks in offspring monocytes such as H3K9 trimethylation have been reported in rodent models (69, 70). These changes have direct consequences on monocyte function by altering expression of genes such as TLR4 and LBP (16). However, the absence of expression differences in LPS receptors CD14 and TLR4 in resting UCB monocytes from obese and lean groups in our study suggests the involvement of other mechanisms that regulate transcription. One example of such a mechanism is chromatin remodeling of cis-regulatory regions of LPS-inducible genes mediated by histone methylation changes and regulatory RNA. Future studies will investigate global changes in histone H3 methylation footprint, combined with expression changes of enhancer and long non-coding RNA using unbiased genome-wide approaches.

Another possibility is that increased in utero exposure to a high-fat diet resulted in altered TLR4 as well as TLR1/2 signaling due to activation by fatty acids (71, 72). Alternatively, maternal obesity may lead to an enhanced inflammatory environment within the placenta, which promotes immune tolerance. Indeed, in non-human primates and humans, maternal obesity resulted in the accumulation of macrophages within the placenta (73), and increased expression of inflammatory molecules IL-1, TNFA, and MCP-1 (74). The contribution of an altered maternal gut microbiome as a consequence of obesity cannot be ruled out either (75). Maternal pregravid obesity also has the potential to alter offspring gut microbiome (76). Additionally, it is still unclear if pregravid obesity alters the placental microbiome (77) and if changes in placental microbiota composition and/or abundance could contribute to the establishment of immune tolerance in the neonate. Future studies should be devoted to understanding and elucidating the relative contributions of maternal obesity-induced mechanisms that lead the neonatal immune system to respond differently during an infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Evelien M. Bunnik, Department of Cell Biology and Neuroscience, UCR for her technical assistance with epigenetics experiments. We would also like to thank Dr. Xinping Cui and Ashley Cacho, Department of Statistics, UCR, for their help with preliminary bioinformatics analysis.

This work was supported by NIH grants KL2TR000152 (N.E.M) and R03AI112808 (I.M) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH under award number UL1TR000128.

Footnotes

ETHICS APPROVAL

The Institutional Ethics Review Boards (IRB) of Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) and University of California Riverside (UCR) approved this research project. All subjects in the study provided signed consent before enrolment.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Gene expression and methylation data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive under accession number SUB2952704 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S, N.E.M, J.Q.P, K.L.T, and I.M conceived and designed the experiments. S.S, R.M.W, and M.R performed the experiments. S.S and R.M.W analyzed the data. S.S and I.M wrote the paper with input from N.E.M, J.Q.P, and K.L.T.

References

- 1.Gaillard R, Durmus B, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW. Risk factors and outcomes of maternal obesity and excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1046–1055. doi: 10.1002/oby.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Reilly JR, Reynolds RM. The risk of maternal obesity to the long-term health of the offspring. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;78:9–16. doi: 10.1111/cen.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leddy MA, Power ML, Schulkin J. The impact of maternal obesity on maternal and fetal health. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2008;1:170–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott-Pillai R, Spence D, Cardwell CR, Hunter A, Holmes VA. The impact of body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a retrospective study in a UK obstetric population, 2004–2011. BJOG. 2013;120:932–939. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rastogi S, Rojas M, Rastogi D, Haberman S. Neonatal morbidities among full-term infants born to obese mothers. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:829–835. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.935324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suk D, Kwak T, Khawar N, Vanhorn S, Salafia CM, Gudavalli MB, Narula P. Increasing maternal body mass index during pregnancy increases neonatal intensive care unit admission in near and full-term infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:3249–3253. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1124082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haberg SE, Stigum H, London SJ, Nystad W, Nafstad P. Maternal obesity in pregnancy and respiratory health in early childhood. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23:352–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffiths PS, Walton C, Samsell L, Perez MK, Piedimonte G. Maternal high-fat hypercaloric diet during pregnancy results in persistent metabolic and respiratory abnormalities in offspring. Pediatr Res. 2016;79:278–286. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumas O, Varraso R, Gillman MW, Field AE, Camargo CA., Jr Longitudinal study of maternal body mass index, gestational weight gain, and offspring asthma. Allergy. 2016;71:1295–1304. doi: 10.1111/all.12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerra S, Sartini C, Mendez M, Morales E, Guxens M, Basterrechea M, Arranz L, Sunyer J. Maternal prepregnancy obesity is an independent risk factor for frequent wheezing in infants by age 14 months. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:100–108. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksson JG, Sandboge S, Salonen MK, Kajantie E, Osmond C. Long-term consequences of maternal overweight in pregnancy on offspring later health: findings from the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study. Ann Med. 2014;46:434–438. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.919728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan AR, Thompson JM, Murphy R, Black PN, Lam WJ, Ferguson LR, Mitchell EA. Obesity and diabetes genes are associated with being born small for gestational age: results from the Auckland Birthweight Collaborative study. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaillard R. Maternal obesity during pregnancy and cardiovascular development and disease in the offspring. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:1141–1152. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0085-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds RM, Allan KM, Raja EA, Bhattacharya S, McNeill G, Hannaford PC, Sarwar N, Lee AJ, Bhattacharya S, Norman JE. Maternal obesity during pregnancy and premature mortality from cardiovascular event in adult offspring: follow-up of 1 323 275 person years. BMJ. 2013;347:f4539. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odaka Y, Nakano M, Tanaka T, Kaburagi T, Yoshino H, Sato-Mito N, Sato K. The influence of a high-fat dietary environment in the fetal period on postnatal metabolic and immune function. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:1688–1694. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myles IA, Fontecilla NM, Janelsins BM, Vithayathil PJ, Segre JA, Datta SK. Parental dietary fat intake alters offspring microbiome and immunity. J Immunol. 2013;191:3200–3209. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farley D, Tejero ME, Comuzzie AG, Higgins PB, Cox L, Werner SL, Jenkins SL, Li C, Choi J, Dick EJ, Jr, Hubbard GB, Frost P, Dudley DJ, Ballesteros B, Wu G, Nathanielsz PW, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE. Feto-placental adaptations to maternal obesity in the baboon. Placenta. 2009;30:752–760. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leibowitz KL, Moore RH, Ahima RS, Stunkard AJ, Stallings VA, Berkowitz RI, Chittams JL, Faith MS, Stettler N. Maternal obesity associated with inflammation in their children. World J Pediatr. 2012;8:76–79. doi: 10.1007/s12519-011-0292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson RM, Marshall NE, Jeske DR, Purnell JQ, Thornburg K, Messaoudi I. Maternal obesity alters immune cell frequencies and responses in umbilical cord blood samples. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26:344–351. doi: 10.1111/pai.12387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adkins B, Leclerc C, Marshall-Clarke S. Neonatal adaptive immunity comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:553–564. doi: 10.1038/nri1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Kleer I, Willems F, Lambrecht B, Goriely S. Ontogeny of myeloid cells. Front Immunol. 2014;5:423. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki T, Hashimoto S, Toyoda N, Nagai S, Yamazaki N, Dong HY, Sakai J, Yamashita T, Nukiwa T, Matsushima K. Comprehensive gene expression profile of LPS-stimulated human monocytes by SAGE. Blood. 2000;96:2584–2591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NEII. Heward JA, Roux B, Tsitsiou E, Fenwick PS, Lenzi L, Goodhead I, Hertz-Fowler C, Heger A, Hall N, Donnelly LE, Sims D, Lindsay MA. Long non-coding RNAs and enhancer RNAs regulate the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in human monocytes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3979. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smallwood SA, Lee HJ, Angermueller C, Krueger F, Saadeh H, Peat J, Andrews SR, Stegle O, Reik W, Kelsey G. Single-cell genome-wide bisulfite sequencing for assessing epigenetic heterogeneity. Nat Methods. 2014;11:817–820. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho HH, Ivashkiv LB. Downregulation of Friend leukemia virus integration 1 as a feedback mechanism that restrains lipopolysaccharide induction of matrix metalloproteases and interleukin-10 in human macrophages. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2010;30:893–900. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun CC, Li SJ, Li G, Hua RX, Zhou XH, Li DJ. Long Intergenic Noncoding RNA 00511 Acts as an Oncogene in Non-small-cell Lung Cancer by Binding to EZH2 and Suppressing p57. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e385. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam LL, Emberly E, Fraser HB, Neumann SM, Chen E, Miller GE, Kobor MS. Factors underlying variable DNA methylation in a human community cohort. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(Suppl 2):17253–17260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121249109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lisanti S, Omar WA, Tomaszewski B, De Prins S, Jacobs G, Koppen G, Mathers JC, Langie SA. Comparison of methods for quantification of global DNA methylation in human cells and tissues. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Gazzar M, Yoza BK, Chen X, Hu J, Hawkins GA, Mccall CE. G9a and HP1 Couple Histone and DNA Methylation to TNF alpha Transcription Silencing during Endotoxin Tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32198–32208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803446200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maurano MT, Wang H, John S, Shafer A, Canfield T, Lee K, Stamatoyannopoulos JA. Role of DNA Methylation in Modulating Transcription Factor Occupancy. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1184–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guha M, Mackman N. LPS induction of gene expression in human monocytes. Cell Signal. 2001;13:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(00)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ilott NE, Heward JA, Roux B, Tsitsiou E, Fenwick PS, Lenzi L, Goodhead I, Hertz-Fowler C, Heger A, Hall N, Donnelly LE, Sims D, Lindsay MA. Corrigendum: Long non-coding RNAs and enhancer RNAs regulate the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in human monocytes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6814. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer D, Van der Weyden MB, Snyderman R, Kelley WN. A role for adenosine deaminase in human monocyte maturation. J Clin Invest. 1976;58:399–407. doi: 10.1172/JCI108484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen MT, Dong L, Zhang XH, Yin XL, Ning HM, Shen C, Su R, Li F, Song L, Ma YN, Wang F, Zhao HL, Yu J, Zhang JW. ZFP36L1 promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation by repressing CDK6. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16229. doi: 10.1038/srep16229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das H, Kumar A, Lin Z, Patino WD, Hwang PM, Feinberg MW, Majumder PK, Jain MK. Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) regulates proinflammatory activation of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6653–6658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Divanovic S, Trompette A, Petiniot LK, Allen JL, Flick LM, Belkaid Y, Madan R, Haky JJ, Karp CL. Regulation of TLR4 signaling and the host interface with pathogens and danger: the role of RP105. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:265–271. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0107021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee CC, Avalos AM, Ploegh HL. Accessory molecules for Toll-like receptors and their function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:168–179. doi: 10.1038/nri3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tontonoz P, Nagy L, Alvarez JG, Thomazy VA, Evans RM. PPARgamma promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell. 1998;93:241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagy L, Tontonoz P, Alvarez JG, Chen H, Evans RM. Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARgamma. Cell. 1998;93:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yarilina A, Xu K, Chen J, Ivashkiv LB. TNF activates calcium-nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT)c1 signaling pathways in human macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1573–1578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gebhard C, Schwarzfischer L, Pham TH, Schilling E, Klug M, Andreesen R, Rehli M. Genome-wide profiling of CpG methylation identifies novel targets of aberrant hypermethylation in myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6118–6128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krausgruber T, Blazek K, Smallie T, Alzabin S, Lockstone H, Sahgal N, Hussell T, Feldmann M, Udalova IA. IRF5 promotes inflammatory macrophage polarization and TH1–TH17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:231–238. doi: 10.1038/ni.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi C, Zhang X, Chen Z, Sulaiman K, Feinberg MW, Ballantyne CM, Jain MK, Simon DI. Integrin engagement regulates monocyte differentiation through the forkhead transcription factor Foxp1. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:408–418. doi: 10.1172/JCI21100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi C, Sakuma M, Mooroka T, Liscoe A, Gao H, Croce KJ, Sharma A, Kaplan D, Greaves DR, Wang Y, Simon DI. Down-regulation of the forkhead transcription factor Foxp1 is required for monocyte differentiation and macrophage function. Blood. 2008;112:4699–4711. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-137018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: new molecules and patterns of gene expression. J Immunol. 2006;177:7303–7311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barker DJ. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1995;311:171–174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Godfrey KM, Lillycrop KA, Burdge GC, Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Epigenetic mechanisms and the mismatch concept of the developmental origins of health and disease. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:5R–10R. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e318045bedb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gluckman PD, Lillycrop KA, Vickers MH, Pleasants AB, Phillips ES, Beedle AS, Burdge GC, Hanson MA. Metabolic plasticity during mammalian development is directionally dependent on early nutritional status. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12796–12800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705667104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burdge GC, Slater-Jefferies J, Torrens C, Phillips ES, Hanson MA, Lillycrop KA. Dietary protein restriction of pregnant rats in the F0 generation induces altered methylation of hepatic gene promoters in the adult male offspring in the F1 and F2 generations. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:435–439. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507352392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lillycrop KA, Slater-Jefferies JL, Hanson MA, Godfrey KM, Jackson AA, Burdge GC. Induction of altered epigenetic regulation of the hepatic glucocorticoid receptor in the offspring of rats fed a protein-restricted diet during pregnancy suggests that reduced DNA methyltransferase-1 expression is involved in impaired DNA methylation and changes in histone modifications. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:1064–1073. doi: 10.1017/S000711450769196X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fu Q, McKnight RA, Yu X, Wang L, Callaway CW, Lane RH. Uteroplacental insufficiency induces site-specific changes in histone H3 covalent modifications and affects DNA-histone H3 positioning in day 0 IUGR rat liver. Physiol Genomics. 2004;20:108–116. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00175.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fu Q, McKnight RA, Yu X, Callaway CW, Lane RH. Growth retardation alters the epigenetic characteristics of hepatic dual specificity phosphatase 5. FASEB J. 2006;20:2127–2129. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6179fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacLennan NK, James SJ, Melnyk S, Piroozi A, Jernigan S, Hsu JL, Janke SM, Pham TD, Lane RH. Uteroplacental insufficiency alters DNA methylation, one-carbon metabolism, and histone acetylation in IUGR rats. Physiol Genomics. 2004;18:43–50. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00042.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klebanoff MA, Meirik O, Berendes HW. Second-generation consequences of small-for-dates birth. Pediatrics. 1989;84:343–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eriksson JG. Proved association between low birth weight and coronary disease in adulthood. Too quick weight gain can disturb the muscle-fat balance. Lakartidningen. 2001;98:5306–5307. 5310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henneke P, Berner R. Interaction of neonatal phagocytes with group B streptococcus: recognition and response. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3085–3095. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01551-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peltier MR, Freeman AJ, Mu HH, Cole BC. Characterization and partial purification of a macrophage-stimulating factor from Mycoplasma hominis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;54:342–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]