Abstract

Purpose:

Family-building after gonadotoxic treatment often requires in vitro fertilization, surrogacy, or adoption, with associated challenges such as uncertain likelihood of success, high costs, and complicated laws regulating surrogacy and adoption. This study examined adolescent and young adult female (AYA-F) survivors’ experiences and decision-making related to family-building after cancer.

Methods:

Semi-structured interviews explored fertility and family-building themes (N=25). Based on an a priori conceptual model, hypothesis coding and grounded theory coding methods guided qualitative analysis.

Results:

Participants averaged 29 years old (SD=6.2); were mostly White and educated. Four major themes were identified: Sources of Uncertainty, Cognitive and Emotional Reactions, Coping Behaviors, and Decision-making. Uncertainty stemmed from medical, personal, social, and financial factors, which led to cognitive, emotional, and behavioral reactions to reduce distress, renegotiate identity, adjust expectations, and consider „next steps’ toward family-building goals. Most AYA-Fs were unaware of their fertility status, felt uninformed about family-building options, and worried about expected challenges. Despite feeling that “action” was needed, many were stalled in decision-making to evaluate fertility or address information needs; postponement and avoidance were common. Younger AYA-Fs tended to be less concerned.

Conclusion:

AYA-Fs reported considerable uncertainty, distress, and unmet needs surrounding family-building decisions post-treatment. Support services are needed to better educate patients and provide opportunity for referral and early preparation for potential challenges. Reproductive counseling should occur throughout survivorship care to address medical, psychosocial, and financial difficulties, allow time for informed decision-making, and the opportunity to prepare for barriers such as high costs.

Keywords: young adult cancer, fertility, infertility, uncertainty, health decision-making, decisional conflict

Introduction

There are more than half a million adolescent and young adult female (AYA-F) cancer survivors in the U.S. and the vast majority hope to have children [1]. Fertility is ranked as among the most distressing survivorship issues, particularly for young women [2–4]. Pre-treatment fertility counseling is now well-accepted as an essential component of AYA cancer care [5, 6]. However, few AYA-Fs receive follow-up fertility care post-treatment [7]. Estimates suggest 62% of AYA-Fs feel uninformed about using assisted reproductive technology (ART) and more than 80% would consider adoption but, among those, 88% are concerned about the process [8–10].

For AYA-Fs who received gonadotoxic therapy, making decisions about alternative family-building options, including in vitro fertilization (IVF), surrogacy, or adoption, involves complex decision-making. Information about reproductive potential are based on estimates and the likelihood of success with different options is largely unknown. It is impossible to predict how many IVF cycles may be needed to achieve pregnancy or the exact nature of adoption processes. It may also be difficult to decide how to spend limited financial resources for the best chance of success.

Although there is growing attention to AYA-Fs’ experiences related to fertility preservation at the time of diagnosis [11, 12], we are not aware of any prior work evaluating AYA-Fs’ decision-making about family-building after cancer. We drew from two theoretical models to build a conceptual model. As specified by the Tripartite Model of Uncertainty, AYAs affected by cancer experience three main sources of uncertainty: medical uncertainty (e.g., inexact estimates of fertility potential), personal uncertainty (e.g., lack of clarity about priorities and values), and social uncertainty (e.g., managing relationships) [13]. Self-Regulation Theory posits that patients’ cognitive and emotional reactions in response to uncertainty are central to and predictive of decision-making and health risk management [14–17]. Young adult survivors report that the most difficult part of healthcare decision-making is managing uncertainty and fear of receiving bad news [18]. We previously found high rates of decision-making difficulty among AYA-Fs in relation to family-building after cancer: 87% felt uninformed, 70% wanted more advice to help manage decisional uncertainty, and 35% wanted more emotional support [19].

Survivors who feel uncertain or overwhelmed by family-building decisions may be at-risk for being unable to have a biologically related child if they delay reproductive healthcare (e.g., due to diminishing ovarian reserve) or may experience greater challenges associated with the medical, psychosocial, legal, and financial barriers. This study aimed to further understand AYA-Fs’ experience of uncertainty and decision-making processes related to family-building after cancer. We hypothesized there would be themes signifying high levels of uncertainty surrounding infertility risk and family-building options, resulting in cognitive and emotional reactions related to quality decision-making (e.g., uninformed, inconsistent with values). Building on prior work and grounded in an a priori self-regulation theoretical model, we sought to examine AYA-F cancer survivors’ decision-making about family-building after cancer.

Methods

Study procedures were approved by the Northwell Health Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Eligibility criteria include: 1) female, 2) aged 15–39 years old, 3) completed gonadotoxic cancer treatment including systemic chemotherapy and/or pelvic radiation, 4) had not had a child since diagnosis, and 5) desired children or undecided family-building plans.

Procedure

Two recruitment strategies were used. Hospital-based recruitment identified patients through electronic medical records (EMR). After obtaining consent from primary clinicians, letters were mailed home with follow-up phone calls to complete enrollment. We also partnered with young adult cancer patient organizations (e.g., Stupid Cancer, Lacuna Loft). Study advertisements (IRB-approved) were posted on organizations’ websites and social media pages providing a brief description of the study and link to provide contact information using a HIPPA-compliant platform. Follow-up calls confirmed eligibility and completed enrollment. For minors (15–17 years old), parental consent and participant assent were obtained. Qualitative interviews were conducted over the phone following a standardized, semi-structured interview guide (Supplemental Table). The interview guide followed our theoretical framework, based in the Tripartite Model of Uncertainty and Self-Regulation Theory. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service, and kept confidential. Interviews lasted 45–60 minutes.

Qualitative Analysis

Guidelines for conducting qualitative research were followed including the use of an audit trail, member checking among the coding team, and saturation [20]. The coding team (CB, ALH, and AM) read all transcripts at least twice and inter-rater reliability was established for all codes (>.70; calculated via the Dedoose qualitative coding platform). Coding used two techniques: hypothesis coding, which involves creating a set of codes based on hypothesized concepts; and grounded theory coding, which is an exploratory approach that allows unexpected but salient themes to emerge from the data [20]. Hypothesis coding was based on our integrated theoretical framework, drawing from the Tripartite Model of Uncertainty, Self-Regulation Theory, prior work, and from the literature [13, 15, 16, 19, 21]. Given family-building costs and cancer financial toxicity effects, we hypothesized that “financial uncertainty” would be a distinct factor and coded it as such; while in the Tripartite Model financial uncertainty is subsumed under personal sources of uncertainty. First, a round of open coding was conducted to confirm and/or modify components of our hypothesized model and initial code set. A code book was created through iterative independent and collaborative analysis. After open coding was completed, codes were evaluated by reviewing participant comments reflecting each code and a collaborative process of interpretation and defining codes. All transcripts were read another time to confirm codes. This second cycle coding also categorized the coded data based on themes and conceptual similarities and attributed meaning in terms of relationships among themes/subthemes. A collaborative approach to finalize our conceptual model ensured accurate representation of coded data and the overall structure of relationships among themes.

Results

The sample (N=25) averaged 29 years old (SD=6.20; range 15–39) and was primarily White (80%), non-Hispanic (84%), and partnered (68%); total income ranged from <$50,000 (36%) to >$100,000 (20%). All AYA-Fs reported a desire for future children, per eligibility criteria; only 32% (n=8) had taken steps to preserve their fertility before treatment. Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample descriptives (N=25).

| Sociodemographic and medical characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Median | Range | |

| Current age (years) | 29.44 (6.20) | 28.00 | 15 – 39 |

| Age at cancer diagnosis (years) ± | 22.68 (8.46) | 22.00 | 9 – 38 |

| Age finished most recent treatment (years) ± | 23.92 (8.12) | 21.50 | 10 – 38 |

| Time since most recent treatment (years)1 | 5.81 (5.43) | 2.00 | 0.5 – 16 |

| Diagnosed in childhood (<15 years old), n=4 | |||

| n | % | ||

| Diagnosis (first cancer) | |||

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 6 | 24.00 | |

| Breast | 5 | 20.0 | |

| Gynecological cancers (Ovarian, Cervical, Uterine) | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Leukemia | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 3 | 12.0 | |

| Anal, rectal, colon, colorectal | 1 | 4.0 | |

| Sarcoma | 1 | 4.0 | |

| Myelodysplastic Syndrome | 1 | 4.0 | |

| Recurrence(s) or secondary primary cancer | 3 | 12.0 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 20 | 80.0 | |

| More than one race | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Other | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 4.0 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| non-Hispanic | 21 | 84.0 | |

| Hispanic | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Relationship status | |||

| Married/partnered | 17 | 68.0 | |

| Geographic locality | |||

| Suburban | 19 | 76.0 | |

| Urban | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Rural | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Annual income (household total) | |||

| Less than $50,000 | 9 | 36.0 | |

| $50,000 - $100, 000 | 9 | 36.0 | |

| More than $100,000 | 5 | 20.0 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Education | |||

| College Degree | 12 | 48.0 | |

| Post-graudate Degree | 7 | 28.0 | |

| High school degree/ Vocational training | 5 | 20.0 | |

| Some high school, no degree | 1 | 4.0 | |

| Employed, full- or part-time | 22 | 88.0 | |

| Family-building characteristics | N | % | |

| Took steps to preserve fertility before treatment2 | 8 | 32.0 | |

| Lupron Injecton | 4 | 16.0 | |

| Froze eggs | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Frozen embroys | 2 | 8.0 | |

| Froze Ovarian Tissue | 1 | 4.0 | |

Variable includes missing data; not included in SD and median calculations

Excluding hormone therapy (e.g., tamoxifen for breast cancer survivors) and long-term targeted therapy (e.g., Gleevec or Herceptin).

Categories not mutually exclusive.

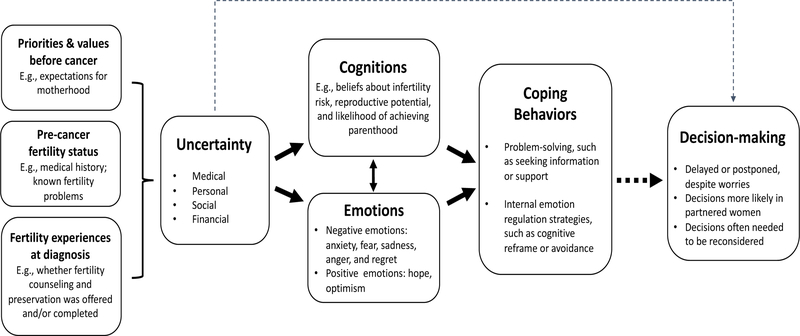

Four major themes were identified: Sources of Uncertainty, Cognitive and Emotional Reactions, Coping Behaviors, and Decision-making. Themes are depicted in Figure 1, with definitions and sample quotes in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Decision-making process of young women considering family-building after cancer.

Model of adolescent and young adult female cancer survivors’ decision-making processes for family-building after cancer, based on a self-regulation theoretical framework. Survivors experience multiple sources of uncertainty after cancer (medical, personal, social, and financial) related to fertility, reproductive potential, and family-building options, which lead to cognitive and emotional reactions; primarily related to expected difficulties of achieving parenthood goals and negative emotions. Coping behaviors include problem-solving and emotion-regulation strategies to manage uncertainty and distress. Decision-making is often delayed or postponed (represented by a dotted line to represent a lack of engagement with decision-making processes) due to uncertainty about personal values related to family-building options, uncertainty about actionable “next step” options, or due to avoidance and postponement of fertility issues as a coping behavior to manage distress.

Table 2.

Qualitative themes of family-building experiences after cancer.

| Themes | Subthemes (% reported) | Definition | Sample quotes± |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sources of Uncertainty | Medical (100%) | - Lack of knowledge about current fertility status and future reproductive potential - Lack of knowledge about how to navigate the health system to obtain fertility care - Unpredictable health future |

“That’s my big thing right now … how do I know how long my fertility window is? Because I’m sure it’s been compromised in some form, but has it been hardly at all or, you know, is it looking like I have one more year of having good fertility to have children? And then from there, you know, what should I do? From there, what path should I take in like preservation or just planning it out?” “So I still have a ton of questions about like what are the next steps. And at what point do I - when do I decide that I want to do this? … What if menopause comes early for me? Because I read somewhere that it could come early now that I’ve been through all of this. Just so many questions.” “Every person’s case is different so it kind of just leaves me more confused and not knowing what kind of fertility specialist to go to or what test to request.” “Trusting your body is pretty important and cancer is a huge trust breaker. I felt fine when I was diagnosed with cancer. I had no idea that there was anything wrong with me, so that breaks that trust relationship you have with your body… it’s so hard to think that it might not break again.” |

| Personal (100%) | - Questioning changes in identity related to expectations for motherhood and family-building goals - Questions about meeting important lifetime milestones, including family-building |

“I don’t feel like a cancer survivor, because cancer took away having children. I can’t carry because of cancer. I can’t move past cancer or accept that I had cancer, because of everything it took away from me. I’m trying to figure that out.” “It was worse than hearing the words, “You have cancer,” ‘cause it’s like you picture yourself as a young woman, “I still have time to build a family,” and now you might not ever be able to have kids.” “People say cancer is the gift that keeps on giving… we have it ten times harder just to do something that ‘normal people’ can just have done no problem and it sucks.” |

|

| Social (100%) | - Uncertainty about how best to communicate about fertility issues with partners, family, and friends - Questions about how best to communicate about potential infertility with future partners |

“I feel like going through this essentially alone. I have my husband who loves me but he doesn’t understand my individual experience, why sometimes I get so frustrated that we can’t have a child like someone normal.” “It makes me feel uncomfortable about ever having that kind of discussion with someone when I am ready to start a family. It’s a situation that is very much outside of my control. And it makes me feel like I’m less than most just because of the fact that I probably can’t have a child.” “If I survive this, how am I gonna tell my future partner, ‘Hey, there’s a high probability that I may never be able to bear a child?”‘ |

|

| Financial (100%) | - Lack of knowledge about potential cost of family-building - Unsure of how to plan for the financial cost of family building |

“What am I going to do next? If I have to use my eggs, how am I going to pay for it? I only took my eggs out; I didn’t make embryos. I’m scared that it’s going to be so expensive. And how much of a burden is that going to be on me?” “Here you are, spending tons of money to retrieve your eggs and freeze them, and if you can’t carry… it’s emotionally damaging if you created embryos, and they’re sitting there, and you can’t even use them because you can’t afford surrogacy.” “I’ve gone to see the general amounts of how much a normal treatment cycle would be and it’s a little overwhelming just to see that number. And especially overwhelming because I’m not even sure if that’s even an option.” |

|

| Cognitive and Emotional Reactions | Cognitions (96%) | - Belief that cancer had caused fertility problems and that family-building would be difficult, relating to distress - Beliefs about time pressures associated with reproductive timeline and impact on reproductive potential, connected to emotions of anxiety and fear - Beliefs about definitions of womanhood and motherhood in relation to fertility |

“I remember breaking down and crying and I’m like this is poison, like, this is going to mess up my body, it’s going to prevent me from ever having kids.” “If having a biological child is my goal, you know, literally the clock is ticking and if I don’t make that decision in a decent time period I’m not giving myself the best chance.” “I’m older and I don’t have much time. And so it’s something that keeps me up at night. I think about it constantly. I really don’t think - I think about the cancer coming back, but at the end of the day the thing that really - the hardest part for me was my fertility and moving forward with that. Like I can deal with the cancer. I can go to chemotherapy, I can go to radiation, I can take hormones, whatever I need to do. I can do that. But the fertility thing is the thing that really got me.” “Cancer took a lot of things from me, but it also took away a piece that is part of your womanhood.” “It’s another thing to feel… like you’re not whole, like you’re not a complete woman, that you’re different than everyone else.” |

| Emotions (100%) | - Anxiety and fear, based in beliefs that family-building will be difficult or unachievable - Depictions of loss (or threat of loss) and subsequent feelings of stress, anxiety, sadness, and anger - For a subgroup, lack of concern and distress, related to beliefs that family-building would be achievable |

“I was scared… you see your friends building their families in kinda the ‘normal way’ and you know that’s not an option for you. What are my options? I don’t know my options. I was scared and incredibly sad and confused. I felt like I was standing in front of a hundred roads that I could go down and there was absolutely no indicator which road I should go down…I had really no direction.” “It was devastating…to me the worst part of all of this was losing my fertility.” “I’m a minor, so I know that by the time I’m thinking about having kids and family-building there will probably be more options for me. I have looked on the news and seen uterine transplants and things like that.” |

|

| Coping Behaviors | Problem-solving (76%) | - Proactive efforts to manage distress and uncertainty, including seeking information and support | “I started looking at other options to figure out more about fertility because I realized that it wasn’t necessarily going to be something that was going to be easily accessible through my own doctor team.” “They have in-house counseling, and I started to go to those counseling sessions, because it helped me understand cancer and infertility, and what was the best option for me.” “I became part of a domestic adoption group on Facebook, and just being able to hear stories from other women and other couples who are going through something very similar to us is just a great resource and it’s a great outlet too emotionally.” |

| Emotion regulation (48%) | - Strategies to manage internal states and negative emotions, so as to avoid feeling overwhelmed and to facilitate emotional recovery after cancer - Efforts to accept or adjust to uncertainty; often in the context of adjusting to the cancer experience as a whole |

“I feel a little bit anxious about it because it’s still sort of up in the air and unknown. I’m trying not to let it overwhelm my emotions… I mean, if it happens, it happens. Great. And if it doesn’t, then we’ll figure something out, right?” “I’m still trying to process what having gone through treatment means for my future and trying to get my body back to being as fit as it was before… I’m still trying to focus on healing and just getting back to myself.” |

|

| Decision making about fertility and family-building | Actively pursuing an option (20%) | - Decisions made, reconsidered, and reframed to account for new information and shifting priorities - Reflection on family-building decisions, amidst ongoing emotional processing of cancer effects on fertility Note: participants described decision making processes, though parenthood had not been achieved yet. |

“It’s an insane amount of money for anybody. I know there’s other forms of building your family, adoption is a big one. I can’t emotionally pursue adoption, because I have these biological embryos. I think making sure that I can try to use these embryos is more mentally healthy for me than whatever financial risks that I take.” (decision to pursue IVF with frozen embryos) “I’m excited to adopt, but I think that it’s always a piece that’s going to make me really sad, and it’s always going to be hard. If you’re sitting at a baby shower when someone else has a belly and you never got to have that, it’s always going to be a hard topic.” (decision to pursue adoption) |

| Not engaged in decision making (80%) | - Delay and avoidance of considering decision options due to uncertainty, feeling overwhelmed or unable to manage negative emotions, and/or needing to recovery emotionally from the cancer experience - Decisions delayed, often despite concerns that action was needed |

“It’s a little upsetting because I don’t know and the unknown is a little scary. And having to make the decisions having to see a doctor is a scary step anyway and then having to find out the answer is kind of almost a deterrent in a way like I don’t want to go because I’m afraid to know but I feel like I should go for my own mental health.” “I have huge concerns. If I had trouble getting pregnant before what makes me think that it’s gonna be easy after. How stressful is the process gonna be? How much time and effort and emotion can I really have to spare to put into the process of getting pregnant.” “[I’m feeling] a little overwhelmed because I’m not sure where to start.” |

Some quotes were double coded and represent more than one theme/subtheme.

Sources of Uncertainty

Participants were queried about medical, personal, social, and financial sources of uncertainty and all endorsed some degree of uncertainty in each domain. Medical uncertainty stemmed from lack of knowledge about current fertility status and reproductive potential and timeline (e.g., rate of diminishing ovarian reserve); risk of cancer-related late effects; and feeling uninformed about how to navigate the health system to obtain fertility care. Survivors felt uncertain about whether they could trust their current health and wondered if they were “strong enough” to carry a pregnancy and the chances for cancer recurrence during pregnancy. A few AYA-Fs worried about the health of a future child, stemming from unknown genetic risks (e.g., “Will my child go through what I went through?”). Personal sources of uncertainty came from self-reflection about changing roles, identity, and priorities after cancer. AYA-Fs were still adjusting to the impact of cancer on their sense of self and the threat of infertility added another dimension to shifting identities, particularly in relation to definitions of womanhood and motherhood. Another source of uncertainty related to social factors, based on questions about how to manage social interactions and relationships with partners, friends, and family, including how to communicate concerns and fears. AYA-Fs without a partner questioned if fertility problems would impact dating, worried about disclosing fertility problems to a future partner, and feared rejection; whereas partnered women questioned whether they were on the same page with their partners regarding feelings and expectations for family-building. Financial uncertainty was discussed in great detail. AYA-Fs were aware that IVF, surrogacy, and adoption are costly, but had a poor sense of the potential financial burden. They wondered if financial barriers would ultimately prevent them from achieving parenthood and were unsure how to plan financially.

Experiences of uncertainty were influenced by personal priorities and values that existed before cancer. All AYA-Fs had pre-cancer expectations that motherhood would be achieved through pregnancy with a biologically related child, which was described as a “natural right.” A few women had known fertility issues prior to cancer including baseline uncertainty about reproductive potential, which compounded concerns about additional treatment-related effects.

All AYA-Fs discussed how fertility experiences at diagnosis impacted their current thoughts and feelings including whether counseling and fertility preservation were offered and/or completed. For some who underwent fertility preservation, having frozen eggs/embryos provided reassurance, though uncertainty was still reported about the process and costs. For others, however, steps taken to preserve fertility did not reduce uncertainty and women still felt unsure about their likelihood of success achieving family-building goals (e.g., “There’s no guarantee that an embryo is going to turn into a baby.”). Some women were unsure as to whether measures taken to preserve fertility had worked (e.g., leuprolide acetate to suppress ovarian function, reducing risk of premature ovarian failure).

Cognitive and Emotional Reactions

In the midst of such uncertainty, AYA-Fs formed beliefs about their reproductive potential and what their journey toward family-building would entail, which were associated with a range of emotional reactions. As depicted in Figure 1, cognitive and emotional reactions had bidirectional influences. Given a lack of fertility counseling post-treatment, AYA-Fs pieced together information from various sources to draw conclusions and make assumptions. Most believed they would have difficulty achieving pregnancy, though very few had undergone a fertility evaluation. In reaction to beliefs about perceived risks and negative expectations, emotions were mostly negative, based in anxiety and fear. At the same time, emotions were also powerful drivers for the pieces of information attended to (confirmation bias), which influenced perceptions and expectations. Heightened fear about a low chance for success appeared to increase AYA-Fs’ focus on the perceived challenges. Survivors felt “pissed off,” anxious, and hurt that family-building options were now limited and grieved this loss. Adolescents who were not included in pretreatment fertility decisions felt “cheated.” Alternatively, optimism that family-building would be possible was associated with lower risk perceptions and less perceived urgency and reproductive time pressures. At times, AYA-Fs described both positive and negative emotions simultaneously (e.g., fear and hope).

Distress was particularly high among older aged survivors and those in life stages in which family-building was a more pressing concern. For AYA-Fs in their late 20s and 30s, beliefs centered on an awareness of reproductive timelines (biologically based and societal expectations) and perceived time pressures; references to “biological clocks” were common, relating to anxiety and fear about missing their reproductive window. There was a sense of urgency to have children “as soon as possible,” which exacerbated anxiety particularly among those who did not yet feel ready for motherhood and among single women. Conversely, younger survivors acknowledged fertility issues may be upsetting in the future but tended to believe advances in reproductive medicine would solve problems, which alleviated worry.

Finally, cognitions about identity and what it means to be a woman and mother also impacted emotional experiences. Per study eligibility criteria, motherhood was something that all AYA-Fs hoped for and for many was considered an essential part of womanhood. While some were uncertain about what fertility challenges meant for their identity (described under Sources of Uncertainty), others had well developed beliefs about loss of womanhood. Risk of infertility and expectations about family-building difficulties threatened their sense of self and what they envisioned their life to be. Cancer had “taken away” options and changed how motherhood would be achieved. Cognitions surrounding the threat or loss of a “natural right” to motherhood led to sadness, resentment, and anger.

Coping Behaviors

These cognitive and emotional reactions related to coping strategies to regulate emotions and manage negative affect (Figure 1). Problem-solving strategies included information seeking to address questions and concerns (e.g., Googling; 60%), connecting with cancer peers with similar experiences (32%), plans to see a fertility specialist and/or pursue a fertility evaluation (36%), speaking to a therapist or counselor (20%), self-care strategies (e.g., exercise, journaling; 16%), and finding support from loved ones (8%). For some, information-seeking alleviated fears and provided reassurance that parenthood was possible; whereas for others, information increased uncertainty and distress due to greater awareness of challenges. Emotion regulation strategies were reported; defined as distinct coping efforts to regulate internal states and manage distress (e.g., cognitive reframing). These were deliberate, proactive attempts to change thoughts and expectations to create more hopeful and optimistic beliefs and emotions (34%) and engender acceptance (20%), often as part of more global efforts to adjust to the entirety of cancer-related changes. One survivor described a storyline from a popular television show depicting a successful uterine transplant, which she used to help maintain confidence that she would be able to carry a child in the future. A few AYA-Fs focused on rationalization to create meaning about cancer and fertility problems (e.g., “part of God’s plan”; 20%).

For some AYA-Fs, fear-related cognitions and emotions appeared to trigger avoidance of threatening information or cognitive minimization of perceived risks (24%). For these survivors, thinking about family-building felt overwhelming and anxiety-provoking. In response, distraction, postponement, and avoidance were effective coping strategies (e.g., “trying to stay busy and not think about it”). For example, fear of receiving bad news and a desire to avoid distressing emotions stopped survivors from seeking a fertility evaluation (as described in Family-building Decision-making). These strategies were reported by AYA-Fs of all ages including among older survivors who simultaneously voiced concerns about age-related fertility decline and reproductive time pressures. Another reason for avoidant coping was perceived financial barriers. AYA-Fs avoided information about costs out of fear of learning costs would be prohibitive and hoped for greater financial security in the future to manage the financial burden.

Family-building Decision-making

The cognitive, emotional, and behavioral/coping reactions to cancer-related fertility impairment (or perceptions of risk) ultimately led to decision-making processes about post-treatment fertility care and family-building (Figure 1). The main theme of decision-making was broadly conceptualized as either making a clear choice about a preferred family-building option and active pursuit of a chosen family-building path; or any consideration of “next steps” related to parenthood goals including intermediary decisions to manage risks such as accessing fertility care and gaining knowledge to ultimately inform family-building decisions and preparation. As some participants were years away from their preferred and expected timeframe for having a child, this definition of decision-making was inclusive of their experiences and the long-term decision-making processes involved in planning for future family-building after cancer.

The majority of AYA-Fs (80%) reported uncertainty about family-building decision options and had not chosen a preferred choice if natural conception was not possible. Having a biologically related child was generally cited as a “first choice,” particularly if AYA-Fs had frozen eggs/embryos stored; and using donor eggs/embryos or adoption was perceived as “back-up” options. Although many acknowledged that back-up plans may be needed, in-depth consideration of what this would involve was limited. Thus, despite beliefs about the challenges ahead, decision-making about preparatory actions to plan for or mitigate risks, such as seeking a fertility evaluation or planning for costs, had also not been considered or only considered superficially. Although many reported proactive coping efforts to manage distress (e.g. information seeking), this did not necessarily translate into consideration of or action toward next steps aligned with future family-building goals.

Different sources of uncertainty seemed to directly affect decision-making, or lack thereof, about next steps. Although many worried about the consequences of postponing fertility issues, AYA-Fs were uncertain about what to do and failed to proactively figure out options. For example, many AYA-Fs hoped to have a biologically related child and feared a shortened reproductive timeline, yet they had not sought a fertility evaluation, despite wondering if they should. Others worried about costs but had not taken steps to learn about expenses or financial planning solutions. Uncertainty about identity and conceptions of motherhood also led to disengagement from considering family-building options, as AYA-Fs were still figuring out what changed expectations for family-building meant for them. Thus, a substantial group of AYA-Fs described a sort of stalled decision-making process in which they were aware (and worried) that they should consider their options and plan for potential future barriers yet refrained from doing so. This was true even among those who reported urgency to have children, high levels of anxiety and fear about potential challenges, and those engaged in proactive coping efforts (e.g., “Googling for information”). Some AYA-Fs recognized a cognitive dissonance as they identified future parenthood as an important life goal and described being fearful of inaction, while at the same time failed to make decisions and take next steps consistent with achieving those goals; and appeared confused by their own contradictory behavior. Alternatively, in association with avoidant coping behaviors, others were clear in their decision to postpone decision-making until the future, when they expected to feel better equipped to cope with challenges.

A subgroup of survivors (20%) were in the beginning stages of pursuing a chosen family-building path. All were partnered and described their decision-making as an ongoing, iterative process. In reflecting on past and current decision-making experiences, survivors described a fluctuating sense of feeling informed and confident at times, juxtaposed with feeling overwhelmed and disheartened as new challenges arose, such as first learning of the complexity of surrogacy laws or being surprised by add-on costs. Unforeseen difficulties and setbacks were common, and decisions were reconsidered, reframed, and renegotiated to account for new information and shifting priorities. Three survivors had first pursued IVF, but after failed attempts started the decision-making process over to consider a second option for achieving parenthood. Some faced decisions about competing priorities of wanting to have a biologically related child but also trying to maximize chances for success within a limited budget. Notably, having chosen a path to pursue family-building did not alleviate fertility distress. Survivors were simultaneously excited and hopeful, while continuing to grieve the experience of cancer and fertility problems.

Discussion

This study proposes a model for how AYA-Fs understand their fertility and make decisions about family-building after cancer. Findings extend our prior research and are consistent with the literature identifying high rates of uncertainty, distress, and decisional conflict related to family-building after cancer [19, 21–25]. Most AYA-Fs in this study were uncertain of their fertility status, believed family-building would be difficult without a guarantee of success, and worried about expected challenges. Coping behaviors included postponement and avoidance of fertility as a way to manage distress. Most AYA-Fs were not fully engaged in fertility-related decision-making, despite being concerned that “next steps” should be taken to prepare for the future. Among those in pursuit of a chosen family-building path, decision-making was described as an ongoing process wrought with unexpected difficulties and set-backs.

To our knowledge, this is the first theoretically driven, evidence-based model of AYA-Fs’ decision-making about family-building after cancer. It is well established that uncertainty and decisional conflict are associated with low quality decision-making (i.e., uninformed, inconsistent with values) and long-term regret and distress [26–28], and may lead to delayed decision-making and avoidance [27]. For AYA-Fs at-risk for premature ovarian failure, delays may cause them to miss their narrowed window of reproductive opportunity. Delays may also prevent opportunities to prepare for future challenges, such as freezing eggs/embryos post-treatment if they were unable to before. Others may consider financial planning strategies to prepare for costs. Greater uncertainty and distress may prevent planning and increase the risk of experiencing difficulties associated with family-building pursuits. While it is true that postponement or avoidance of fertility issues may be adaptive coping strategies for managing current distress, there may also be consequences of delaying care. Many survivors will experience little or no difficulty achieving parenthood or will be well-equipped to overcome barriers in the future. For others, however, early consideration of potential barriers may be important in determining future likelihood of success and mitigating potential challenges. The challenges and lack of preparation for difficulties was observed among AYA-Fs who had initiated family-building plans. It is also not clear that postponement and avoidance do in fact lead to lower distress. It may be that AYA-Fs would prefer to address fertility and family-building issues if they were confident in having access to support and resources. Consistent with principles of patient-centered care, survivors should be informed about risks and options – and adequately supported – in order to facilitate decisions that are consistent with their values, priorities, and long-term goals including the option of deciding to postpone or delay considerations.

There is a clear need for follow-up fertility counseling that is aligned with individual needs and parenthood goals. Most oncofertility research has focused on pre-treatment fertility preservation [29, 30]. Fertility counseling at diagnosis should be followed up after treatment to provide continuity of care as patients transition to survivorship with evolving questions and concerns [31–33]. Most AYA-Fs are uninformed about their fertility and family-building options post-treatment [12]. Improving access to medical and supportive care resources aligned with their readiness to have discussions may help alleviate fears, correct misbeliefs, and create hope that motherhood is possible. Providing support along with information about risks and potential barriers is critical to help survivors cope with distress including fear of receiving bad news and low self-efficacy to manage challenges.

Finally, for some AYA-Fs, family-building will be far in the future and survivors may not perceive these issues as a priority. Self-regulation strategies often lead people to prioritize immediate, concrete experiences over future, abstract events, which can dissuade people from taking steps that have future benefit [14]. For example, undergoing a fertility evaluation presents an immediate threat (e.g., receiving bad news), whereas benefits (e.g., greater chances for risk management and family-building success) may not be experienced for a while. Clinical discussions that clarify short- vs. long-term costs and benefits may be important. Targets of intervention may include helping survivors recognize tradeoffs and make decisions aligned with their goals and priorities.

Limitations

The study primarily included White non-Hispanic AYA-Fs recruited via social media outreach, which may limit the generalizability of findings. Adolescents (15–17 years old), compared to young adults (18–39 years old), were also under-represented. Social media recruitment may lead to overestimation of cancer-related distress including related to fertility [34]. Greater effort to engage diverse patient subgroups and employ methodology that leads to representative samples of the target population is needed. Specific exploration of adolescents’ experiences is also warranted. Longitudinal decision-making processes were not assessed, and challenges may change over time.

Conclusion

This study highlights the need to address fertility and family-building issues in post-treatment survivorship care as many AYA-Fs are uncertain, distressed, and may be at-risk for medical, psychosocial, legal, and financial challenges associated with family-building after cancer. Counseling about family-building should be brought up early in survivorship care to allow time for informed decision-making, timely referral, and planning opportunity. Resources may also be needed to help survivors build coping and self-management skills to regulate distressing emotions and build confidence to pursue information and care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the support provided from our patient organization partners with recruitment efforts, including Stupid Cancer, Lacuna Loft, The Samfund, GRYT Health, Alliance for Fertility Preservation, and Army of Women.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R03CA212924, PI: Catherine Benedict) and through the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA008748, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest: Catherine Benedict is a member of the Stupid Cancer Board of Directors, a Research Advisor to GRYT Health, and a member of the Advisory Council for the Alliance for Fertility Preservation. There are no financial relationships to disclose.

Human Rights: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Northwell Health Institutional Review Board; Protocol #16–876) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Welfare of Animals: This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- [1].van Dijk M, van den Berg MH, Overbeek A, et al. Reproductive intentions and use of reproductive health care among female survivors of childhood cancer. Hum Reprod 2018; 33: 1167–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Cancer 2013; 119: 201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Keegan THM, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv 2012; 6: 239–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gorman JR, Su HI, Roberts SC, et al. Experiencing reproductive concerns as a female cancer survivor is associated with depression. Cancer 2015; 121: 935–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Quinn GP, Block RG, Clayman ML, et al. If you did not document it, it did not happen: rates of documentation of discussion of infertility risk in adolescent and young adult oncology patients’ medical records. J Oncol Pract 2015; 11: 137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lewin J, Ma JMZ, Mitchell L, et al. The positive effect of a dedicated adolescent and young adult fertility program on the rates of documentation of therapy-associated infertility risk and fertility preservation options. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25: 1915–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kim J, Mersereau JE, Su HI, et al. Young female cancer survivors’ use of fertility care after completing cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24: 3191–3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shay LA, Parsons HM, Vernon SW. Survivorship care planning and unmet information and service needs among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2017; 6: 327–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jukkala AM, Azuero A, McNees P, et al. Self-assessed knowledge of treatment and fertility preservation in young women with breast cancer. Fertil Steril 2010; 94: 2396–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gorman JR, Whitcomb BW, Standridge D, et al. Adoption consideration and concerns among young adult female cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2017; 11: 149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang Y, Anazodo A, Logan S. Systematic review of fertility preservation patient decision aids for cancer patients. Psychooncology 2019; 28: 459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Logan S, Perz J, Ussher JM, et al. A systematic review of patient oncofertility support needs in reproductive cancer patients aged 14 to 45 years of age. Psychooncology 2018; 27: 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Donovan EE, Brown LE, LeFebvre L, et al. ‘The uncertainty is what is driving me crazy’: the tripartite model of uncertainty in the adolescent and young adult cancer context. Health Commun 2015; 30: 702–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cameron LD, Biesecker BB, Peters E, et al. Self-regulation principles underlying risk perception and decision making within the context of genomic testing. Soc Personal Psychol Compass; 11 Epub ahead of print May 2017. DOI: 10.1111/spc3.12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Clark NM, Gong M, Kaciroti N. A Model of Self-Regulation for Control of Chronic Disease. Health Educ Behav 2014; 41: 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med 2016; 39: 935–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Diefenbach MA, Leventhal H. The common-sense model of illness representation: Theoretical and practical considerations. J Soc Distress Homeless 1996; 5: 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shay LA, Schmidt S, Cornell SD, et al. ‘Making my own decisions sometimes’: a pilot study of young adult cancer survivors’ perspectives on medical decision-making. J Cancer Educ 2018; 33: 1341–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Benedict C, Thom B, N Friedman D, et al. Young adult female cancer survivors’ unmet information needs and reproductive concerns contribute to decisional conflict regarding posttreatment fertility preservation. Cancer 2016; 122: 2101–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Saldana J The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Second Edition London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Benedict C, McLeggon J-A, Thom B, et al. ‘Creating a family after battling cancer is exhausting and maddening’: Exploring real-world experiences of young adult cancer survivors seeking financial assistance for family building after treatment. Psychooncology 2018; 27: 2829–2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Benedict C, Shuk E, Ford JS. Fertility issues in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2016; 5: 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gorman JR, Bailey S, Pierce JP, et al. How do you feel about fertility and parenthood? The voices of young female cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2012; 6: 200–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schover LR. Motivation for parenthood after cancer: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs 2005; 2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Halliday LE, Boughton MA. Exploring the concept of uncertain fertility, reproduction and motherhood after cancer in young adult women. Nursing Inquiry 2011; 18: 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Garvelink MM, Boland L, Klein K, et al. Decisional Conflict Scale findings among patients and surrogates making health decisions: part II of an anniversary review. Med Decis Making 2019; 39: 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].O’Connor A Ottawa Decision Support Framework, https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/odsf.html.

- [28].O’Connor AM, Jacobsen MJ, Stacey D. An evidence-based approach to managing women’s decisional conflict. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing 2002; 31: 570–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ehrbar V, Urech C, Tschudin S. Fertility decision-making in cancer patients – current status and future directions. Expert Review of Quality of Life in Cancer Care 2018; 3: 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Müller M, Urech C, Boivin J, et al. Addressing decisional conflict about fertility preservation: helping young female cancer survivors’ family planning decisions. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2018; 44: 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Rubinsak LA, Christianson MS, Akers A, et al. Reproductive health care across the lifecourse of the female cancer patient. Support Care Cancer 2019; 27: 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Murphy D, Klosky JL, Reed DR, et al. The importance of assessing priorities of reproductive health concerns among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer. Cancer 2015; 121: 2529–2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Murphy D, Orgel E, Termuhlen A, et al. Why healthcare providers should focus on the fertility of AYA cancer survivors: it’s not too late! Front Oncol 2013; 3: 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Benedict C, Hahn AL, Diefenbach MA, et al. Recruitment via social media: advantages and potential biases (In press). Digital Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.