Abstract

Background: The rapidly evolving coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020. It was first detected in the Wuhan city of China and has spread globally resulting in a substantial health and economic crisis in many countries. Observational studies have partially identified different aspects of this disease. There have been no published systematic reviews that combine clinical, laboratory, epidemiologic, and mortality findings. Also, the effect of gender on the outcomes of COVID-19 has not been well-defined.

Methods: We reviewed the scientific literature published from January 1, 2019 to May 29, 2020. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA (version 14, IC; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The pooled frequency with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was assessed using random effect model. P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant publication bias.

Results: Out of 1,223 studies, 34 satisfied the inclusion criteria. A total of 5,057 patients with a mean age of 49 years were evaluated. Fever (83.0%, CI 77.5–87.6) and cough (65.2%, CI 58.6–71.2) were the most common symptoms. The most prevalent comorbidities were hypertension (18.5%, CI 12.7–24.4) and Cardiovascular disease (14.9%, CI 6.0–23.8). Among the laboratory abnormalities, elevated C-Reactive Protein (CRP) (72.0%, CI 54.3–84.6) and lymphopenia (50.1%, CI 38.0–62.4) were the most common. Bilateral ground-glass opacities (66.0%, CI 51.1–78.0) was the most common CT scan presentation. The pooled mortality rate was 6.6%, with males having significantly higher mortality compared to females (OR 3.4; 95% CI 1.2–9.1, P = 0.01).

Conclusion: COVID-19 has caused a significant number of hospitalization and mortality worldwide. Mortality associated with COVID-19 was higher in our study compared to the previous reports from China. The mortality was significantly higher among the hospitalized male group. Further studies are required to evaluate the effect of different variables resulting in sex disparity in COVID-19 mortality.

Keywords: coronavirus, COVID-19, mortality, male, pandemic

Introduction

Facing an immediate crisis by the novel coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) which has been called the once in a century pathogen, requires a global response (1). The disease caused by this virus has been named “coronavirus disease 2019” (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO). As of now, more than 180 countries have reported COVID-19 patients. Given the increasing number of countries infected with SARS-CoV-2, WHO finally classified COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (2). The SARS-CoV-2 virus is a beta-coronavirus, belonging to the same coronavirus family as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome virus (MERS-CoV) and SARS-CoV. MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV were previously responsible for respiratory syndrome outbreaks. However, COVID-19 is the first virus of the coronavirus family to cause a pandemic (3).

COVID-19 started in China in December 2019 when a cluster of patients with pneumonia of unknown origin were identified in the city of Wuhan. Since then, it has infected hundreds of thousands of people around the world and resulted in more than 539,900 deaths up to this date (4). Despite governmental travel restrictions in many countries, the confirmed number of new cases has been rising globally. The international community has asked for at least 675 million US dollars to use for preparedness and protection of states with weaker health systems (5).

In the previous two outbreaks of coronaviral respiratory illness, namely Severe Acute Respiratory Illness (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Illness (MERS), gender-based differences in mortality were observed. In SARS, mortality risk was twice as high in younger males compared to younger females, but this difference in mortality decreased with older age. Additionally, the case fatality rate observed in males was twice that of females in MERS (6). The effect of sex on COVID-19 mortality was unknown. In our systematic review, we compared male and female mortality risk for COVID-19.

The novelty of COVID-19 has raised many questions about the epidemiology of the disease, clinical and laboratory methods of diagnosis, as well as therapeutic measures. Many observational studies have been dealing with these features separately. Further combined systematic reviews are needed, to understand the role of sex in COVID-19 associated mortality. In this meta-analysis study, we reviewed the published literature from January 1, 2019 to May 29, 2020 to provide a comprehensive overview of COVID-19.

Methods

Search Strategy

We searched Pubmed/Medline, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library for studies published from January 1, 2019 to May 29, 2020. The search strategy was based on the following key-words: COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, nCoV disease, SARS2, COVID19, Wuhan coronavirus, Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus, 2019-nCoV, coronavirus disease-19, coronavirus disease 2019, 2019 novel coronavirus and Wuhan pneumonia. Lists of references of selected articles and relevant review articles were hand-searched to identify further studies. This study was conducted and reported according to the PRISMA guidelines (7). The study did not require Institutional Review Board approval.

Study Selection

The records found through database searching were merged and the duplicates were removed using EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA). Two reviewers (YF and PJ) independently screened the records by title and abstract to exclude those not related to the current study. The full texts of potentially eligible records were retrieved and evaluated by a third reviewer (AT). Included studies met the following inclusion criteria: (i) patients were confirmed and diagnosed with RT-PCR as suggested by WHO; (ii) The raw data for clinical, radiological and laboratory findings were included; and (iii) the outcomes were addressed. Studies with insufficient information about patients' characteristics and outcomes were excluded. Case reports, reviews, and animal studies were also excluded. Only studies written in English were selected.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A data extraction form was designed by two reviewers (AZ and SH). These reviewers extracted the data from all eligible studies and differences were resolved by consensus. The following data was extracted: first author name; year of publication; type of study; country(ies) where the study was conducted; distribution of age and sex in the population; number of patients investigated; data for clinical, radiological, and laboratory findings; and outcomes.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with STATA (version 14, IC; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The pooled frequency with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was assessed using random effect model. The between-study heterogeneity was assessed by Cochran's Q and the I2 statistic. Publication bias was assessed statistically by using Begg's and Egger's tests (p < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistically significant publication bias).

Quality Assessment

The checklist provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) was used to perform quality assessment (8).

Results

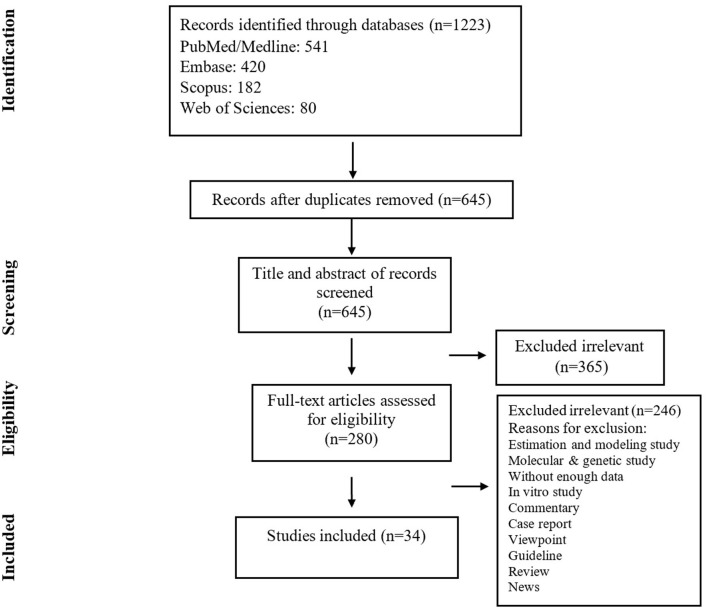

The search yielded 1,223 publications, of which 280 potentially eligible studies were identified for full-text review, resulting in 34 studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria (Figure 1) (Table 1). A total of 5,057 patients were included, of which the mean age was 49.0 years. Based on JBI tool, the included studies had a low risk of bias.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| First author | Country | Published time | Type of study | Mean age | Male/female | Nationality | No. of patients | Diagnostic methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hui et al. (9) | China | 14, Jan, 2020 | Case series | NR | NR | Chinese | 41 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Xia et al. (10) | China | 26, Feb, 2020 | Case series | 54.5 | 21M, 9F | Chinese | 30 | RT-PCR |

| Xu et al. (11) | China | 13, Feb, 2020 | Case series | 41 | M35, F27 | Chinese | 62 | RT-PCR |

| Zhang et al. (12) | China | 7, Feb, 2020 | Case series | NR | NR | Chinese | 178 | RT-PCR |

| To et al. (13) | China | 12, Feb, 2020 | Case series | 62.5 | 7M, 5F | Chinese | 12 | RT-PCR |

| Zou et al. (14) | China | 19, Feb, 2020 | Correspondence | 59 | 9M,9F | Chinese | 18 | RT-PCR |

| Hoehl et al. (15) | Germany | 3, Mar, 2020 | Correspondence | 35 | NR | German | 126 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Pan et al. (16) | China | 24, Feb, 2020 | Correspondence | NR | NR | Chinese | 82 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Tang et al. (17) | China | 19, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 54 | 98M, 85F | Chinese | 183 | RT-PCR |

| Chung et al. (18) | China | 4, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 51 | M13, F8 | Chinese | 21 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Fang et al. (19) | China | 19, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 45 | 29M, 22F | Chinese | 51 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Guan et al. (20) | China | 28, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 47 | 640M,459F | Chinese | 1099 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Huang et al. (21) | China | 24, Jan, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 49 | 30M,11F | Chinese | 41 | RT-PCR |

| Kui et al. (22) | China | 7, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 57 | 61M,76F | Chinese | 137 | RT-PCR |

| Li et al. (23) | China | 29, Jan, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 52 | M238, F187 | Chinese | 425 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Liu et al. (24) | China | 9, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 53.6 | 8M, 4F | Chinese | 12 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Wang et al. (25) | China | 7, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 56 | 75M, 63F | Chinese | 138 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Wu et al. (26) | China | 29, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 46 | 39M, 41F | Chinese | 80 | RT-PCR |

| Zhang et al. (27) | China | 19, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 57 | 71M,69F | Chinese | 140 | RT-PCR |

| Ai et al. (28) | China | 26, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 48.5 | M467, F547 | Chinese | 1014 | RT-PCR/CT scan |

| Pan et al. (29) | China | 13, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 40 | 6M, 15F | Chinese | 21 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Shi et al. (30) | China | 24, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 49.5 | 42M, 39F | Chinese | 81 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Yang et al. (31) | China | 21, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 59.7 | 35M, 17F | Chinese | 52 | RT-PCR |

| Bajema et al. (32) | China | 4, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | NR | 115M, 95F | Chinese | 210 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Bernheim et al. (33) | China | 20, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 45.3 | 61M, 60F | Chinese | 121 | RT-PCR |

| Chen et al. (34) | China | 15, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 55.5 | 67M, 32F | Chinese | 99 | RT-PCR |

| Pan et al. (35) | China | 13, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 45 | 33M, 30F | Chinese | 63 | RT-PCR |

| Xu et al. (36) | China | 21, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 44 | 29M, 21F | Chinese | 50 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Xu et al. (37) | China | 28, Feb, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 50 | 39M, 51F | Chinese | 90 | RT-PCR |

| Chang et al. (38) | China | 7, Feb, 2020 | Research letter | 34 | 10M, 3F | Chinese | 13 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Chen et al. (39) | China | 26, Feb, 2020 | Research letter | NR | NR | Chinese | 85 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Kwok et al. (40) | China | 7, Feb, 2020 | Research letter | 59.8 | 9M, 5F | Chinese | 14 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Hansen et al. (41) | Norway | 23 April, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 72.5 | 28M,14F | Norwegian | 42 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

| Yu et al. (42) | China | 14, May, 2020 | Cross-sectional | 64 | 139 M, 87 F | Chinese | 226 | RT-PCR/CT-scan |

Clinical Manifestations and Comorbidities

The most common signs and symptoms were fever (83.0%, CI 77.5–87.6), cough (65.2%, CI 58.6–71.2), dyspnea (27.4%, CI 19.6–35.2), myalgia/fatigue (34.7%, CI 26.0–44.4), and Sputum production (17.2%, CI 10.8–26.4). Less common symptoms included hemoptysis (2.4%, CI 0.8–6.7), diarrhea (5.7%, CI 3.8–8.6), and nausea/vomiting (5.0%, CI 2.3–10.7) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of comorbidities.

| Pooled frequency | n/N* | Publication bias | Heterogeneity test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (p-value) | (p-value) | I2 (%) | p value | ||

| Smoking | 8.0 (2.3–13.6) | 172/1,332 | 0.06 | 100 | 0.00 |

| Hypertension | 18.5 (12.7–24.4) | 306/1,800 | 0.98 | 100 | 0.00 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 14.9 (6.0–23.8) | 178/2,031 | 0.72 | 100 | 0.00 |

| Diabetes | 10.8 (8.3–13.3) | 166/1,932 | 0.39 | 100 | 0.00 |

| Pulmonary disease | 3.4 (0.8–6.0) | 39/2,031 | 0.72 | 100 | 0.00 |

| Malignancies | 2.8 (0.8–4.8) | 33/1,816 | 0.74 | 100 | 0.00 |

| Chronic liver disease | 8.1 (4.6–11.6) | 29/546 | 0.45 | 100 | 0.00 |

| Renal disease | 4.4 (0.24–8.6) | 17/1,472 | 0.33 | 100 | 0.00 |

n, number of patients with comorbidity; N, total number of patients.

The most common comorbidities were hypertension (18.5%, CI 12.7–24.4), cardiovascular diseases (14.9%, CI 6.0–23.8), diabetes (10.8%, CI 8.3–13.3), chronic liver disease (8.1, CI 4.6–11.6) and smoking (8.0%, CI 2.3–13.6), respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of clinical manifestations.

| Pooled frequency | n/N* | Publication bias | Heterogeneity test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (p-value) | I2 (%) | p-value | ||

| Fever | 83.0 (77.5–87.6) | 2,073/2,465 | 0.76 | 86 | 0.00 |

| Cough | 65.2 (58.6–71.2) | 1,689/2,515 | 0.80 | 85 | 0.00 |

| Dyspnea | 27.4 (19.6–35.2) | 477/2,014 | 0.42 | 89 | 0.00 |

| Myalgia/fatigue | 34.7 (26.0–44.4) | 742/1,938 | 0.60 | 89 | 0.00 |

| Sputum production | 17.2 (10.8–26.4) | 480/1,862 | 0.01 | 89 | 0.00 |

| Sore throat | 14.5 (10.6–19.5) | 224/1,577 | 0.88 | 66 | 0.00 |

| Headache | 11.1 (7.7–15.7) | 230/1,864 | 0.30 | 74 | 0.00 |

| Diarrhea | 5.7 (3.8–8.6) | 104/2,041 | 0.77 | 66 | 0.00 |

| Hemoptysis | 2.4 (0.8–6.7) | 20/1,339 | 0.77 | 100 | 0.00 |

| Anorexia | 10.1 (1.0–57.2) | 82/1,322 | 0.73 | 98 | 0.00 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 5.0 (2.3–10.7) | 65/1,563 | 0.90 | 85 | 0.00 |

| Dizziness | 8.6 (2.5–26.0) | 16/205 | 0.90 | 65 | 0.00 |

| Chest tightness | 8.4 (2.5–26.0) | 24/256 | 0.24 | 78 | 0.00 |

| Rhinorrhea | 9.3 (2.2–31.0) | 28/232 | 0.17 | 88 | 0.00 |

| Chills | 14.3 (3.0–47.4) | 12/111 | NA | 86 | 0.00 |

Lab Abnormalities and Complications

The most frequent abnormal laboratory findings in patients with COVID-19 were, respectively, elevated C-Reactive Protein (CRP) (72% CI 54.3–84.6), lymphopenia (50.1%, CI 38.0–62.4), elevated Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) (41%, CI 22.8–62.0), elevated serum aspartate aminotransferase (19.7%, CI 10.5–33.7), and thrombocytopenia (11.1%, CI 7.7–15.7) (Table 4). Among the confirmed COVID-19 subjects, 14.0% (CI, 6.7–29.0) had viremia. Impaired hepatic function with ALT levels >47.25 U/L was seen in 13.3% (CI 3.2–41.0) of COVID-19 subjects. Acute cardiac injury with troponin levels >28 pg/ml was seen in 12.4% (CI 6.2–23.2). Acute kidney injury was found in 5.5% (CI 1.3–20.8). Shock was reported in 4.0% (CI 1.6–12.0). Finally, 13.0% (CI 4.8–30.0) met the definition of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Table 4.

Meta-analysis of laboratory findings.

| Pooled frequency | n/N* | Publication bias | Heterogeneity test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (p-value) | I2 (%) | p-value | ||

| Lymphopenia | 50.1 (38.0–62.4) | 1,122/1,853 | 0.08 | 93 | 0.00 |

| Lymphocytosis | 33.5 (2.4–90.2) | 55/93 | NA | 88 | 0.00 |

| Neutrophilia | 29.7 (19.3–42.7) | 60/191 | 0.51 | 58.7 | 0.08 |

| Leukopenia | 28.0 (20.0–37.4) | 544/1,798 | 0.89 | 88 | 0.00 |

| Leukocytosis | 10.8 (5.8–19.1) | 165/1,829 | 0.86 | 92 | 0.00 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 11.1 (7.7–15.7) | 343/1,393 | 0.00 | 86 | 0.00 |

| Anemia | 43.5 (30.3–57.7) | 79/179 | NA | 72 | 0.00 |

| Decreased albumin | 51.8 (2.0–98.0) | 105/191 | 0.99 | 96 | 0.00 |

| High CRP | 72.0 (54.3–84.6) | 918/1,681 | 0.02 | 96 | 0.00 |

| High LDH | 41.0 (22.8–62.0) | 408/1,393 | 0.32 | 94 | 0.00 |

| High ESR | 79.7 (66.6–88.5) | 143/179 | NA | 69 | 0.00 |

| High AST | 19.7 (10.5–33.7) | 267/1,474 | 0.70 | 93 | 0.00 |

| High ALT | 14.6 (7.6–26.3) | 191/1,290 | 0.99 | 84.8 | 0.00 |

| High creatinine kinase | 14.1 (8.3–23.0) | 142/1,453 | 0.20 | 84 | 0.00 |

| High bilirubin | 7.9 (2.9–19.0) | 95/1,278 | 0.96 | 89 | 0.00 |

| High creatinine | 3.3 (1.2–9.1) | 20/1,294 | 0.13 | 74 | 0.00 |

| High troponin I | 2.4 (0.3–15.0) | 1/41 | NA | 0.00 | 0.1 |

Radiological Characteristics

Chest X-Ray (CXR) and Chest CT scan were the most common imaging modalities used for the diagnosis of COVID-19. The pooled sensitivity of CT scan for detecting COVID-19 was 79.3%. The most common sites of the lung involvement based on chest CT scan were right lower lobe (76.2%, CI 57.8–82.5) followed by the left lower lobe (71.8%, CI 57.8–82.5). Most of the patients (74.8%) had bilateral involvement. The most common pattern of parenchymal involvement was ground-glass opacities (66.0%, CI 51.1–78.0). The Chest CT scan was reported normal in 20.7% of the patients with confirmed RT-PCR results (Table 5).

Table 5.

Meta-analysis of imaging findings.

| CT Scan | Patterns | Pooled frequency | n/N* | Publication bias | Heterogeneity test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (p-value) | I2 (%) | p-value | ||||

| Location of involvement | Number of affected lobe | Unaffected | 20.7 (15.1–27.6) | 33/161 | 0.18 | 0.0 | 0.57 |

| 1 lobe | 14.8 (7.4–24.0) | 52/318 | 0.22 | 73 | 0.00 | ||

| 2 lobes | 9.5 (6.5–12.8) | 30/318 | 0.32 | 0.0 | 0.50 | ||

| 3 lobes | 11.7 (7.9–14.6) | 36/318 | 0.64 | 0.0 | 0.50 | ||

| 4 lobes | 15.8 (10.3–20.7) | 49/318 | 0.90 | 40 | 0.15 | ||

| 5 lobes | 37.2 (32.0–42.3) | 118/318 | 0.50 | 30 | 0.22 | ||

| Affected lobe (s) | RUL | 56.8 (50.6–62.8) | 145/255 | 0.12 | 52 | 0.10 | |

| RML | 48.6 (42.5–54.8) | 124/255 | 0.07 | 0.0 | 0.48 | ||

| RLL | 76.2 (65.5–84.4) | 193/255 | 0.14 | 64 | 0.03 | ||

| LUL | 56.0 (47.1–64.7) | 153/255 | 0.12 | 0.0 | 0.40 | ||

| LLL | 71.8 (57.8–82.5) | 167/234 | 0.30 | 76 | 0.01 | ||

| Laterality | Uni lateral | 28.8 (16.6–45.2) | 62/205 | 0.80 | 77 | 0.01 | |

| Bi lateral | 70.6 (55.3–82.5) | 142/205 | 0.20 | 74 | 0.01 | ||

| Pattern of involvement | Pattern of involvement | No involvement | 17.2 (11.4–25.0) | 193/1,080 | 0.42 | 63.0 | 0.04 |

| Both of GGO* & consolidation | 39.0 (28.1–51.0) | 57/142 | NA | 25 | 0.24 | ||

| GGO without consolidation | 66.0 (51.1–78.0) | 846/1,365 | 0.67 | 90 | 0.00 | ||

| Consolidation without GGO | 9.4 (3.3–23.6) | 26/274 | 0.21 | 82 | 0.00 | ||

| Laterality | Uni lateral | 21.8 (12.0–36.3) | 101/507 | 0.63 | 87 | 0.00 | |

| Bi lateral | 74.8 (62.5–84.0) | 405/548 | 0.29 | 84 | 0.00 | ||

GGO, Ground Glass Opacities.

Outcomes

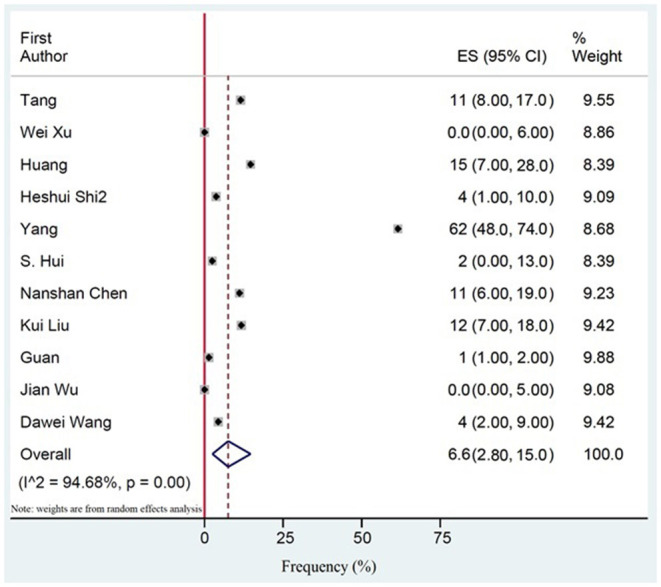

94.6% (CI 73.8–99.1) of the patients with severe COVID-19 were hospitalized. The pooled mortality rate of these patients was 6.6% (CI 2.8–15.0) (Tables 6, 7). Old age, male sex, presence of underlying diseases, higher level of D-dimer, lower level of fibrinogen and anti-thrombin, progressive radiographic deterioration on follow up CT scans, development of ARDS, and requirement of mechanical ventilation were all reported factors associated with increased mortality rate. As shown in Table 8, men had significantly higher mortality in the hospital compared to women (OR 3.4; 95% CI 1.2–9.1, P = 0.01). Although ICU admission was higher in men, the difference was not statistically significant. The mean duration between the time of hospitalization and death was 17.5 days with minimum and maximum periods of 14 and 21 days, respectively. The effects and summaries calculated using a random-effects model weighted by the study population is shown in Figure 2.

Table 6.

Meta-analysis of complications.

| Pooled frequency | n/N* | Publication bias | Heterogeneity test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (p-value) | I2 (%) | p-value | ||

| RNAemia | 14.0 (6.7–29.0) | 6/41 | NA | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| ARDS | 13.0 (4.8–30.0) | 142/1,794 | 0.67 | 96 | 0.00 |

| Acute cardiac injury | 12.4 (6.2–23.2) | 28/243 | 0.83 | 65 | 0.03 |

| Acute kidney injury | 5.5 (1.3–20.8) | 34/1,441 | 0.58 | 93 | 0.00 |

| Liver failure | 13.3 (3.2–41.0) | 20/144 | 0.50 | 84 | 0.00 |

| Shock | 4.0 (1.6–12.0) | 32/1,389 | 0.60 | 86 | 0.00 |

| Hospitalization | 94.6 (73.8–99.1) | 1,561/1,829 | 0.76 | 98 | 0.00 |

Table 7.

Meta-analysis of outcomes.

| Pooled frequency | n/N* | Publication bias | Heterogeneity test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | (p-value) | I2 (%) | p-value | ||

| Discharged | 52.7 (36.5–68.4) | 486/948 | 0.44 | 93 | 0.00 |

| Death | 6.6 (2.8–15.0) | 111/2,026 | 0.50 | 93 | 0.00 |

Table 8.

Mortality and ICU admission in men vs. women in patients with COVID-19.

| Pooled OR | p-value | Heterogeneity test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p-value | ||

| Mortality in men vs. women | 3.4 (1.2–9.1) | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.6 |

| ICU admission in men vs. women | 1.6 (0.7–3.2) | 0.1 | 0.00 | 0.5 |

Figure 2.

The pooled mortality rate of patients with COVID-19. Effects and summaries were calculated using a random-effects model weighted by study population.

Discussion

We evaluated the signs and symptoms, diagnostic modalities, therapeutic measures, and epidemiologic features of COVID-19 to have a better understanding of this pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2. The pooled mortality rate of these patients was 6.6% overall. We detected several factors that contributed to a worsened outcome including old age, male sex, presence of underlying diseases, and abnormal laboratory finding such as an elevated D-Dimer. Although there was not a significant difference between male and female gender in ICU admissions, male gender showed a significantly higher in-hospital mortality rate.

D-Dimer >1 μg/mL was identified as an associative factor that increased odds of in-hospital death in a study by Zhou et al. (p = 0.0033) (43).

Another significant finding in our analysis was the incidence of cardiac injury in 12.4% of the patients, which is a common event seen in a multitude of viral illnesses (44). Gao et al. observed that subjects with influenza (H7N9) and cardiac injury had an elevated risk of mortality (HR = 2.06) (45). In a study by Ludwig et al. which analyzed cardiac biomarkers in influenza patients, 24% of the subjects showed acute cardiac injury ≤30 days after influenza diagnosis and half of the injuries included myocardial infarctions (46). Although our analysis did not show increased mortality risk in patients with cardiac injury, these findings could indicate the potential need for identifying and optimizing cardiac risk factors in COVID-19 patients during the treatment period.

The mean duration between hospitalization and death was 17.5 days (range: 4–21 days), compared to 17.4 days in SARS (47). The overall mortality rate in this study was 6.6%, which is more than twice that was reported earlier (20). Though comparable mortality was reported by Li et al. (7%) and Qian et al. (8.9%) in their meta-analyses, a study by Rodriguez et al. showed a much higher death rate of 13.9% (48–50). On the other hand, a study from the Jiangsu province of China results showed a high cure rate equal to 96.67%. Although the main reason for very low mortality in this study remains unknown, measures including early recognition and centered-quarantine may be contributing factors (51).

Of note, the in-hospital mortality of males was significantly higher than that of females (OR 3.4; 95% CI 1.2–9.1, P = 0.01). A similar pattern of higher mortality in males has been reported in previous coronavirus outbreaks of SARS and MERS. Karlberg et al. also reported that the gender-based difference in mortality was higher in younger males (0–44 years) (RR = 2), compared to those of age group 45–74 (RR-1.45) (52). Similarly, the study by Alghamdi et al. showed that the case fatality rate in males was twice that of females in MERS (52 vs. 23%) (6). Although a gender-based difference in the immune response to infections has been suggested as a possible factor, other contributing factors including smoking history and severity of underlying comorbidities cannot be ruled out (53). This is especially of significance in China, where the prevalence of smoking among men (57.6%) is almost 10 times higher that of women (6.7%) (54). This difference in mortality opens the discussion for the need to treat COVID-19 more aggressively in males, including the possibility of earlier intubation and mechanical ventilation in this population. Cigarette Smokers showed to have a higher expression of Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in lower airways. As it was discussed, ACE2 is the receptor for SARSCoV-2 in the lower respiratory tracts. This finding suggests that smokers are at a higher risk for COVID-19 (55). Therefore we emphasize on smoking cessation especially in the male group with COVID-19. Men smoke more than five times as much as women. (35% in males compared to 6% in females). Although this ratio varies in different countries, it is true that men smoke more in almost all countries (56). These findings can suggest part of the reason behind the significant higher mortality in males with COVID-19. Further investigations are needed to understand this phenomenon.

According to Xiaochen Li et al. male, elder age, leukocytosis, high LDH level, cardiac injury, hyperglycemia and chronic corticosteroid use were related to a higher risk of death in COVID-19. Male group counted for slightly more than half of all their patients (50.9%), however 56.9% of the severe COVID-19 cases were males compared to 45.2% females (P = 0.006). They showed that 19.2% of patients with severe COVID-19 were smokers (57).

Ruan et al. studied 68 deceased cases and 82 discharged ones to identify the clinical predictors of COVID-19 mortality, they found a significant difference among patients with Cardiovascular diseases (p < 0.001), however, their study didn't show any significant difference in sex ratio between the death group and the discharge group. (P < 0.43) (58).

Obesity is a risk factor for comorbid conditions such as cardiovascular diseases which are associated with a higher COVID-19 related deaths. Simonnet et al. showed that invasive mechanical ventilation was significantly associated with male sex (p < 0.05) and Body Mass Index (BMI) (p < 0.05), independent of age, diabetes, and hypertension (59). Previous studies had shown a low mortality rate in obese and morbid obese patients presenting with ARDS which is defined as obesity paradox. There is still more data required to identify whether this paradox is broken by COVID-19 (60).

According to Zirui Tay et al. there may be alleles on the location of ACE2 on X-chromosome that confer resistance to COVID-19. This may explain the lower mortality among females. Additionally, estrogen and testosterone sex hormones can modulate the immune response. Therefore, the disease severity may vary based on the hormonal immunoregulation effect (61). In general testosterone have an immunosuppressive effect and estrogen enhances the immunity. Females are less susceptible to viral infections (62).

Recent studies have shown that estrogen upregulates ACE2 in human atrial myocardium by modulating the local Renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS). Apart from ACE2, Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 is also encoded on X-chromosome. TLR7 mediates several immune cell responses (63). Berghöfer et al. showed that in vitro exposure of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to TLR7 ligands results in higher production of interferon-α (IFNα) in cells from females compared to the cells from males (64).

The mechanisms by which androgens such as testosterone decrease the immune response has not been fully understood. Rettew et al. evaluated the acute effect of testosterone through in vitro treatment of macrophages generated in absence of androgen. The result was a significant decrease in TLR4 expression and sensitivity to a TLR4-specific ligand. In vivo removal of testosterone resulted in significantly increased TLR4 cell surface expression and higher sensitivity to endotoxin. This may indicate an important mechanism of testosterone immunosuppressive effect (65).

Similar to the sex-based differences in SARAS-CoV2, some studies related to SARS-CoV infection have shown a higher mortality and severity of the disease in males. Karlberg et al. showed a significantly higher case fatality rate in males compared females infected with SARS-CoV (p < 0.0001) (52). Channappanavar et al. evaluated the susceptibility to SARS-CoV infection in male mice compared to the age-matched female group. Ovariectomy or estrogen receptor antagonist treatment of female mice showed increased mortality in the SARS-CoV infected mice indicating a protective effect of estrogen receptor signaling (66).

Although around 70% of health and social care workforce worldwide are women and they are in potential exposure to sick patients, most of the studies have shown a higher overall mortality among men with COVID-19. More research is needed to investigate how sex results in different outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (63).

This study has several limitations. Due to the rapidly emerging COVID-19 situation around the globe and the novelty of this coronavirus, there is still limited clinical data regarding diagnostic modalities and effective therapeutic measures. Most of the clinical findings were from observational studies. Future clinical trials and animal models are also required to have conclusive clinical information. More studies outside China are needed for comprehensive results that reflect COVID-19 epidemiology globally. Due to the lack of accurate reports of the new cases in different countries, the epidemiologic measures are also limited. As this pandemic is growing fast, future studies are needed for the evaluation of epidemiologic and clinical features of COVID-19.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has presented with a significant number of mortalities especially among the males around the world. The high rate of hospitalization and case fatality among hospitalized patients along with the lack of intensive care facilities necessitated the identification of the risk factors associated with severe disease and mortality. Males had a significant higher risk of mortality compared to females in our study which was higher than the previous reports from the studies done in China. The reason behind the gender and sex disparity in COVID-19 mortality is still unclear. COVID-19 has been an emerging, rapidly evolving situation. There is still a lot of unknown features of COVID-19 for the broad scientific community to study and identify the risk factors and possible causes of a worse outcome among these patients.

Future Direction

Further studies are essential on the role of sex hormones on mortality in COVID-19. Moreover, social, lifestyle, and environmental factors should be investigated to understand gender difference in COVID-19 mortality. Studying risk factors associated with mortality can assist us to develop a precise prognostic tool and to personalize treatment in COVID-19.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

MN and MMi: conception and design of study. AT, YF, MA, SHas, PJ, and MN: acquisition of data. MN and MMi: analysis and/or interpretation of data. SHad, MMu, MN, and MMi: drafting and revision of manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. MN was supported by Department of Research of the School of Medicine (Grant number: 22960), Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

References

- 1.Gates B. Responding to Covid-19 — a once-in-a-century pandemic? N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1677–9. 10.1056/NEJMp2003762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Summary: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/summary.html (accessed March 12, 2020).

- 3.Peeri NC, Shrestha N, Rahman MS, Zaki R, Tan Z, Bibi S, et al. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol. (2020) dyaa033. 10.1093/ije/dyaa033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lukelsu Coronavirus Dashboard (GEOG 4046 Example). (2020). Available online at: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/90b89509931e4c309e83d7f51e101a08 (accessed June 10, 2020).

- 5.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180:1–11. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alghamdi IG, Hussain II, Almalki SS, Alghamdi MS, Alghamdi MM, El-Sheemy MA, et al. The pattern of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive epidemiological analysis of data from the Saudi Ministry of Health. Int J Gen Med. (2014) 7:417–23. 10.2147/IJGM.S67061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Internal Med. (2009) 151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual 2014. The Systematic Review of Prevalence and Incidence Data Adelaide. Adelaide, SA: The Joanna Briggs Institute; (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui DS, Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. (2020) 91:264–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol. (2020) 92:589–94. 10.1002/jmv.25725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu X-W, Wu X-X, Jiang X-G, Xu K-J, Ying L-J, Ma C-L, et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ. (2020) 368:m792. 10.1136/bmj.m792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Du R-H, Li B, Zheng X-S, Yang X-L, Hu B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. (2020) 9:386–9. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.To KK-W, Tsang OTY, Chik-Yan Yip C, Chan K-H, Wu T-C, Chan J, et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) ciaa149. 10.1093/cid/ciaa149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1177–9. 10.1056/NEJMc2001737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoehl S, Berger A, Kortenbusch M, Cinatl J, Bojkova D, Rabenau H, et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in returning travelers from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1278–80. 10.1056/NEJMc2001899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan Y, Zhang D, Yang P, Poon LL, Wang Q. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect Dis. (2020) 20:411–2. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thrombosis Haemost. (2020) 18:844–7. 10.1111/jth.14768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, Zhang N, Huang M, Zeng X, et al. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Radiology. (2020) 295:202–7. 10.1148/radiol.2020200230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang Y, Zhang H, Xie J, Lin M, Ying L, Pang P, et al. Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR. Radiology. (2020) 200432. 10.1148/radiol.2020200432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y, Liang W-h, Ou C-q, He J-x, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1708–20. 10.1101/2020.02.06.20020974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. (2020) 395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kui L, Fang Y-Y, Deng Y, Liu W, Wang M-F, Ma J-P, et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J. (2020) 133:1025–31. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1199–207. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Yang Y, Zhang C, Huang F, Wang F, Yuan J, et al. Clinical and biochemical indexes from 2019-nCoV infected patients linked to viral loads and lung injury. Sci China Life Sci. (2020) 63:364–74. 10.1007/s11427-020-1643-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. (2020) 323:1061–9. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J, Liu J, Zhao X, Liu C, Wang W, Wang D, et al. Clinical characteristics of imported cases of COVID-19 in Jiangsu Province: a multicenter descriptive study. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) ciaa199. 10.1093/cid/ciaa199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, Yuan YD, Yang YB, Yan YQ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. (2020) 75:1730–41. 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. (2020) 200642. 10.1148/radiol.2020200642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, Gui S, Liang B, Li L, et al. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology. (2020) 295:715–21. 10.1148/radiol.2020200370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:727–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Liu H, Wu Y, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. (2020) 8:475–81. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bajema KL, Oster AM, McGovern OL, Lindstrom S, Stenger MR, Anderson TC, et al. Persons evaluated for 2019. Novel coronavirus—United States, january 2020. Morb Mortal Week Rep. (2020) 69:166–70. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6906e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, Yang Y, Fayad ZA, Zhang N, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. (2020) 295:3. 10.1148/radiol.2020200463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. (2020) 395:507–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan Y, Guan H, Zhou S, Wang Y, Li Q, Zhu T, et al. Initial CT findings and temporal changes in patients with the novel coronavirus pneumonia (2019-nCoV): a study of 63 patients in Wuhan, China. Eur Radiol. (2020) 30:3306–9. 10.1007/s00330-020-06731-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Y-H, Dong J-H, An W-m, Lv X-Y, Yin X-P, Zhang J-Z, et al. Clinical and computed tomographic imaging features of novel coronavirus pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2. J Infection. (2020) 80:394–400. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu X, Yu C, Qu J, Zhang L, Jiang S, Huang D, et al. Imaging and clinical features of patients with 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Eur J Nuclear Med Mol Imag. (2020) 47:1275–80. 10.1007/s00259-020-04735-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang D, Lin M, Wei L, Xie L, Zhu G, Cruz CSD, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infections involving 13 patients outside Wuhan, China. JAMA. (2020) 323:1092–3. 10.1001/jama.2020.1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen W, Lan Y, Yuan X, Deng X, Li Y, Cai X, et al. Detectable 2019-nCoV viral RNA in blood is a strong indicator for the further clinical severity. Emerg Microbes Infect. (2020) 9:469–73. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1732837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwok KO, Wong V, Wei VWI, Wong SYS, Tang JW-T. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) cases in Hong Kong and implications for further spread. J Infect. (2020) 80:671–93. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ihle-Hansen H, Berge T, Tveita A, Rønning EJ, Ernø PE, Andersen EL, et al. COVID-19: symptoms, course of illness and use of clinical scoring systems for the first 42 patients admitted to a Norwegian local hospital. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen. (2020) 140:7. 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu Y, Xu D, Fu S, Zhang J, Yang X, Xu L, et al. Patients with COVID-19 in 19 ICUs in Wuhan, China: a cross-sectional study. Crit Care. (2020) 24:219. 10.1186/s13054-020-02939-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. (2020) 395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greaves K, Oxford JS, Price CP, Clarke GH, Crake T. The prevalence of myocarditis and skeletal muscle injury during acute viral infection in adults: measurement of cardiac troponins I and T in 152 patients with acute influenza infection. Arch Internal Med. (2003) 163:165–8. 10.1001/archinte.163.2.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao C, Wang Y, Gu X, Shen X, Zhou D, Zhou S, et al. Association between cardiac injury and mortality in hospitalized patients infected with avian influenza A (H7N9) virus. Crit Care Med Soc. (2020) 48:451–8. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ludwig A, Lucero-Obusan C, Schirmer P, Winston C, Holodniy M. Acute cardiac injury events </=30 days after laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infection among U.S. veterans, 2010-2012. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2015) 15:109. 10.1186/s12872-015-0095-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng D, Jia N, Fang L-Q, Richardus JH, Han X-N, Cao W-C, et al. Duration of symptom onset to hospital admission and admission to discharge or death in SARS in mainland China: a descriptive study. Trop Med Int Health. (2009) 14:28–35. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02188.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qian K, Deng Y, Tai Y, Peng J, Peng H, Jiang L. Clinical characteristics of 2019. novel infected coronavirus pneumonia:a systemic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). 10.1101/2020.02.14.20021535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li L-Q, Huang T, Wang Y-Q, Wang Z-P, Liang Y, Huang T-B, et al. 2019 novel coronavirus patients' clinical characteristics, discharge rate and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J Med Virol. (2020) 92:577–83. 10.1002/jmv.25757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Gutiérrez-Ocampo E, Villamizar-Peña R, Holguin-Rivera Y, Escalera-Antezana JP, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a ystematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. (2020) 34:101623. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun Q, Qiu H, Huang M, Yang Y. Lower mortality of COVID-19 by early recognition and intervention: experience from Jiangsu Province. Ann Intensive Care. (2020) 10:33. 10.1186/s13613-020-00650-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karlberg J, Chong DS, Lai WY. Do men have a higher case fatality rate of severe acute respiratory syndrome than women do? Am J Epidemiol. (2004) 159:229–31. 10.1093/aje/kwh056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klein SL. The effects of hormones on sex differences in infection: from genes to behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2000) 24:627–38. 10.1016/S0149-7634(00)00027-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang T, Barnett R, Jiang S, Yu L, Xian H, Ying J, et al. Gender balance and its impact on male and female smoking rates in Chinese cities. Soc Sci Med. (2016) 154:9–17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leung JM, Yang CX, Tam A, Shaipanich T, Hackett TL, Singhera GK, et al. ACE-2 Expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID-19. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). 10.1101/2020.03.18.20038455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ritchie H. Who Smokes More, Men or Women? (2019). Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/who-smokes-more-men-or-women (accessed September 02, 2019).

- 57.Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang K, Tao Y, Zhou Y, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2020) 146:110–8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46:846–8. 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, Raverdy V, Noulette J, Duhamel A, et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity. (2020) 28:1195–9. 10.1002/oby.22831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Engin AB, Engin ED, Engin A. Two important controversial risk factors in SARS-CoV-2 infection: obesity and smoking. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. (2020) 78:103411. 10.1016/j.etap.2020.103411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tay MZ, Poh CM, Rénia L, MacAry PA, Ng LFP. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. (2020) 20:363–74. 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taneja V. Sex hormones determine immune response. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1931. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gebhard C, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Neuhauser HK, Morgan R, Klein SL. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol Sex Differ. (2020) 11:29. 10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berghöfer B, Frommer T, Haley G, Fink L, Bein G, Hackstein H. TLR7 ligands induce higher IFN-alpha production in females. J Immunol. (2006) 177:2088–96. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rettew JA, Huet-Hudson YM, Marriott I. Testosterone reduces macrophage expression in the mouse of toll-like receptor 4, a trigger for inflammation and innate immunity. Biol Reprod. (2008) 78:432–7. 10.1095/biolreprod.107.063545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Channappanavar R, Fett C, Mack M, Ten Eyck PP, Meyerholz DK, Perlman S. Sex-based differences in susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J Immunol. (2017) 198:4046–53. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material.