Abstract

Dietary fat consumption during accelerated stages of mammary gland development, such as peripubertal maturation or pregnancy, is known to increase the risk for breast cancer. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. Here we examined the gene expression profile of mouse mammary epithelial cells (MMECs) on exposure to a high‐fat diet (HFD) or control diet (CD). Trp53 −/− female mice were fed with the experimental diets for 5 weeks during the peripubertal period (3‐8 weeks of age). The treatment showed no significant difference in body weight between the HFD‐fed mice and CD‐fed mice. However, gene set enrichment analysis predicted a significant enrichment of c‐Myc target genes in animals fed HFD. Furthermore, we detected enhanced activity and stabilization of c‐Myc protein in MMECs exposed to a HFD. This was accompanied by augmented c‐Myc phosphorylation at S62 with a concomitant increase in ERK phosphorylation. Moreover, MMECs derived from HFD‐fed Trp53 −/− mouse showed increased colony‐ and sphere‐forming potential that was dependent on c‐Myc. Further, oleic acid, a major fatty acid constituent of the HFD, and TAK‐875, an agonist to G protein‐coupled receptor 40 (a receptor for oleic acid), enhanced c‐Myc stabilization and MMEC proliferation. Overall, our data indicate that HFD influences MMECs by stabilizing an oncoprotein, pointing to a novel mechanism underlying dietary fat‐mediated mammary carcinogenesis.

Keywords: breast cancer, c‐Myc, high‐fat diet, mammary gland, oleic acid

We analyzed mammary gland epithelial cells derived from Trp53 −/− mice fed a high‐fat diet. This revealed a possibility that fatty acids induce stabilization of c‐Myc in mammary gland epithelial cells through enhancement of mitogenic signaling.

Abbreviations

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- CD

control diet

- Cdkn1a

cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor 1A

- CHX

cycloheximide

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- FFA

free fatty acid

- FFAR

free fatty acid‐binding receptor

- GPR40

G protein‐coupled receptor 40

- GSK‐3β

glycogen synthase kinase‐3β

- IB

immunoblotting

- HFD

high‐fat diet

- Klk8

kallikrein‐8

- Max

Myc‐associated factor X

- MMEC

mouse mammary epithelial cell

- NEFA

nonesterified fatty acids

- OA

oleic acid

- P‐

phosphorylated

- PA

palmitic acid

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- Rb

retinoblastoma protein

- rh

recombinant human

1. INTRODUCTION

Various biological and epidemiological studies have reported that dietary fat consumption is one of the major risk factors that increases the prevalence of breast cancer. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 The majority of health hazards related to excessive fat intake are associated with being overweight or obese. However, additional evidence in nonobese mouse models has indicated that HFD alone, and not the associated obesity, is responsible for mammary carcinogenesis. The proliferation of MMECs is known to be stimulated by high fat intake independent of body weight. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Furthermore, HFD induces inflammatory cytokines and growth factors, which ultimately cause mammary tumors in nonobesogenic mice. 7 , 11 Additionally, the incidence of premenopausal mammary tumor is higher among red meat‐consuming healthy‐weight individuals than overweight individuals. Hence, these previous findings propose that excessive fat consumption directly facilitates mammary carcinogenesis.

Exposure to HFD during the peripubertal stage (3‐8 weeks of age) in mice has been shown to increase the risk of developing mammary tumors in later life, suggesting sustaining an irreversible effect of high fat intake. 7 , 8 , 9 Moreover, such exposure to a HFD is sufficient to promote murine MMEC proliferation and enhance the recruitment of eosinophils and mast cells. 7 Excessive intake of dietary fat during this pubertal transition period has been shown to decrease event‐free survival time in a 7,12‐dimethylbenzanthracene‐induced mouse mammary tumor model. 8 Similarly, BALB/c mice carrying xenografted Trp53‐null mammary gland have been reported to develop spindle cell carcinoma more frequently, which resembles the human claudin‐low type breast cancer upon high‐fat feeding. 9

P53 is a tumor suppressor that engages in diverse cellular processes including cell cycle regulation, DNA repair machinery, senescence, and apoptosis. Specifically, TP53 mutations manifest in 30% of human breast carcinomas and more than 80% of triple‐negative breast cancers. 12 Trp53 −/− mice are susceptible to a range of tumors including lymphomas, which frequently develop at 6 months of age. 13 Hence, mammary tumors rarely appear during the short lifespan of Trp53 −/− unless additional factors are involved. Thus, in most of the studies, mammary carcinogenesis with Trp53‐null status is investigated using alternative approaches. One such common method is to transplant Trp53 −/− mammary epithelium into a host mouse. 9 However, this procedure has been suggested to disrupt the innate interaction between mammary epithelium and surrounding host tissue. 14

In the present study, we fed Trp53 −/− mice with HFD or CD during the peripubertal stage and cultured MMECs for a defined period to analyze the gene expression profile. Furthermore, we determined differentially expressed genes between the MMECs derived from HFD‐fed and CD‐fed mice to identify molecules that potentially link HFD to mammary carcinogenesis. Gene set enrichment analysis of microarray data predicted that c‐Myc oncoprotein‐targeted genes were significantly enriched in the MMECs from HFD‐fed mice compared to those detected in CD‐fed mice. Furthermore, our findings suggest that HFD elevates c‐Myc stability and protein levels through alteration in its phosphorylation status. Based on these findings, we propose a potential mechanism whereby irrespective of obesity, excessive fat intake during puberty contributes to mammary tumorigenesis.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Mice and diets

The Trp53 −/− mice 15 were obtained from RIKEN BRC (#CDB0001K), interbred, and maintained in a cohort. Wild‐type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan) at 3 weeks of age. Trp53 −/− female mice were randomly assigned to a specific diet, CD or HFD. They were fed from 3 weeks of age to 8 weeks of age. The HFD (D12492, 60% kcal fat) and CD (D12450B, 10% kcal fat) were purchased from Research Diets (Table S1). The HFD was replaced every 2 days as this diet is susceptible to oxidation. Littermates were equally distributed between groups. Mice were housed in polysulfone cages and received food and water ad libitum. They were maintained under aseptic conditions and exposed to a 12:12 hour light : dark cycle with a relative humidity of 45%‐50% at 20‐24°C. Mouse experiments were undertaken in accordance with a Kanazawa University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee‐approved protocol (AP‐153426).

2.2. Genotyping of mice

Mouse genomic DNA was isolated from the cut tails of the mouse after digestion in a buffer containing 0.1 mol/L Tris‐HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mmol/L EDTA, 0.25 mol/L NaCl, 0.2% SDS, and 100 mg/mL proteinase K at 55°C. Polymerase chain reaction was carried out to identify the genotype according to a method published previously. 16

2.3. Mouse mammary epithelial cell isolation and culture

Mouse mammary glands were isolated from 8‐week‐old female Trp‐53 −/− mice that had been fed with HFD or CD for 5 weeks. The mammary tissue was dissociated with 1 mL collagenase/hyaluronidase (#07912; STEMCELL Technologies) and 9 mL DMEM/F‐12 (048‐29785; Wako) supplemented with 5% FBS (#SH30079; HyClone) for 6 hours at 37°C with occasional pipetting and vortexing. To make the dissociation process fast, tissue was minced beforehand. The resultant material was further dissociated to obtain the single‐cell suspension using 0.25% trypsin‐EDTA (3 minutes) at 37°C, followed by 5 mg/mL Dispase (Life Technologies) and 1 mg/mL DNase I (1 min) (Sigma‐Aldrich). The cell suspension was filtered through 40 µm mesh (#352340; Falcon). The MMECs were enriched in the sample by removing unwanted cells such as hematopoietic, endothelial, and fibroblastic cells (CD45+, TER119+, CD31+, and BP‐1+) using EasySep Mouse Epithelial Cell Enrichment kit (#19758; STEMCELL Technologies) and Purple EasySep magnet (18 000; STEMCELL Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Enriched MMECs were cultured on 0.1% (w/v) gelatin‐coated (Iwaki) dishes in FBS‐free Complete EpiCult‐B Medium (Mouse) (#05610; STEMCELL Technologies) supplemented with 10 ng/mL rh bFGF (PeproTech), 10 ng/mL rh EGF (PeproTech), 4 µg/mL (0.0004%) heparin (#07980; STEMCELL Technologies), and 5 µg/mL insulin (Sigma‐Aldrich). 17 , 18 , 19

2.4. MCF10A cell culture

MCF10A cells were cultured in Mammary Epithelial Growth Media (CC‐3150; Lonza) supplemented with 0.1 µg/mL cholera toxin solution (Wako).

2.5. Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted from MMECs with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cyanine‐3‐labeled cRNA was prepared from 0.2 µg RNA using the Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by RNAeasy column purification (Qiagen). Dye incorporation and cRNA yield were checked with the NanoDrop ND‐1000 Spectrophotometer. The microarray analysis was carried out with Whole Mouse Genome microarray 4 × 44K version 2.0 (G2519F #26655; Agilent). The fluorescence intensity was measured with Agilent DNA Microarray Scanner (G2539A). Data were normalized and filtered with 3 filters using GeneSpring software 12.1 (Agilent). In brief, raw data were normalized with their 75 percentile values. These microarray data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE144328). The normalized microarray results were analyzed by the weighted average difference method. 20 Enrichment analysis by EnrichR (version 2.1) was undertaken by R. 21 , 22 Gene set enrichment analysis (A) was carried out on signal to noise metrics using gene sets obtained from H hallmark gene sets and C2 curated gene sets, which are freely available at http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp. 23

2.6. Reverse transcription‐qPCR

Reverse transcription‐qPCR was carried out on total RNA isolated from cultured MMECs using TRIzol (#15596018; Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Isolated RNA was reverse‐transcribed at 37°C with random primers to obtain cDNA, and the qPCR analysis was done as described previously. 24 , 25 TaqMan primers used in the qPCR were c‐Myc (Mm00487803_m1), Mycn (Mm00627179_m1), Mycl1 (Mm00493155_m1), Cdkn1a (Mm04205640_g1), Klk8 (Mm00501179_m1), and Actb (Mm00607939_s1).

2.7. Antibodies and IB

Mouse mammary epithelial cell were lysed by RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail (25 955; Nacalai Tesque) and the whole‐cell lysate was obtained for IB analysis. Enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (WBKLS0500; Millipore, MA01821) was used to obtain the signals and visualize bands using the ImageQuant LAS4000 chemiluminescent image system. Quantification of the band intensity was undertaken using ImageJ‐NIH software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). c‐Myc (9402), P‐c‐Myc‐(S62) (E1J4K) (13 748), p44/42 MAPK (9102), P‐p44/42 MAPK (T202/Y204), GSK‐3β (D5C5Z) XP(R) (12 456), P‐GSK‐3β (S9) (D85E12) (5558) XP(R), P‐Rb(S807/811) (9308), cyclin D1 (2926), PCNA (D3H8P) XP(R) (13 110), anti‐mouse IgG HRP‐linked (7076), and anti‐rabbit IgG HRP‐linked (7074) Abs were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti‐Myc (phospho‐Thr58) (Y011034), anti‐A‐tubulin mouse MAB (DM1A) and Rb (C‐15) sc:50 Abs were purchased from Applied Biological Materials, EMD Millipore, and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, respectively.

2.8. Protein half‐life assay

Primary MMECs were treated with 10 µg/mL CHX (C7698; Sigma‐Aldrich), and whole‐cell lysate was collected at 0, 10, 25, 45, and 60 minutes and immunoblotted with the Ab to c‐Myc.

2.9. Colony formation assay

Mouse mammary epithelial cells were dissociated and resultant single cells were plated at 4000 cells/well in a 60‐mm dish. Colonies were stained with modified Giemsa solution after 14 days of incubation, and the positive area for staining was quantified using ImageJ‐NIH software. The experiment was repeated using different mouse pairs (experiment and control groups) at different passage numbers of cells.

2.10. Mammosphere assay

Cells in monolayer culture were dissociated, filtered through 40‐µm cell strainer to obtain single‐cell suspension, and seeded at a density of 2500 cells/well onto a 96‐well ultralow adherence plate (EZ‐BindShut II; AGC Techno Glass) containing 1% methylcellulose containing αMEM medium supplemented with B27 (Life Technologies), 20 ng/mL rh EGF (Wako), and 20 ng/mL rh bFGF (Wako). After 14 days of incubation, mammospheres were visualized under an inverted phase‐contrast microscope, and BZ software was used to analyze on BZ‐9000 (Keyence) equipped with a hybrid cell counting module. The experiment was repeated using MMECs obtained from different mouse pairs including littermates.

2.11. Fatty acid treatments

Mouse mammary epithelial cells were cultured in FBS‐free complete EpiCult‐B medium (Mouse) (#05610; STEMCELL Technologies) as described above and treated with 3 mmol/L BSA‐conjugated OA (stock solution; #O3008) (Sigma‐Aldrich) or 30% w/v fatty acid‐free BSA (015‐23871; Wako) alone for 48 hours. For the PA treatment, BSA‐conjugated PA 3 mmol/L stock solution was prepared according to a protocol described previously using sodium palmitate (P9767; Sigma‐Aldrich) and BSA (A7030; Sigma‐Aldrich) and treated for 48 hours. 26

2.12. Serum fatty acid analysis

Nonesterified fatty acids present in serum were quantified using a LabAssay NEFA kit (Wako) using the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.13. G protein‐coupled receptor 40 stimulation

Mouse mammary epithelial cells were cultured in FBS‐free complete EpiCult‐B medium (Mouse) (#05610; STEMCELL Technologies) as described above and treated with 100 nmol/L GPR40 agonist (TAK‐875; ChemScene) or DMSO (Nacalai Tesque).

2.14. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis was carried out on 4‐µm specimens obtained from paraffin‐embedded mammary glands. Tissue slides were stained with the Ab to PCNA ([D3H8P] XP[R] [13 110]; Cell Signaling Technology) using a DAB+ Substrate Chromogen detection system (Dako) and counter‐stained with hematoxylin.

2.15. Inhibitor treatment

Mouse mammary epithelial cells were treated with a Myc inhibitor, 10058‐F4, 5‐[(4‐ethylphenyl)methylene]‐2‐thioxo‐4‐thiazolidinone (Tokyo Chemical Industries) or with a MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 (1,4‐diamino‐2,3‐dicyano‐1,4‐bis(2‐aminophenylthio) butadiene) (Selleck Chemicals).

2.16. Statistical analysis

Student’s t test and 2‐way ANOVA tests were used for the statistical analysis. P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software) and basic statistic tools available in Microsoft Excel were used in statistical analysis. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, and ****P < .0001.

3. RESULTS

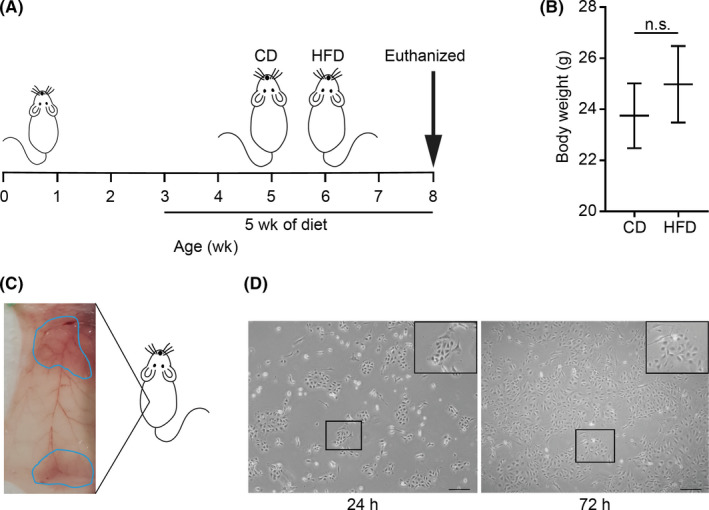

3.1. High‐fat diet promotes MMEC proliferation before inducing obesity

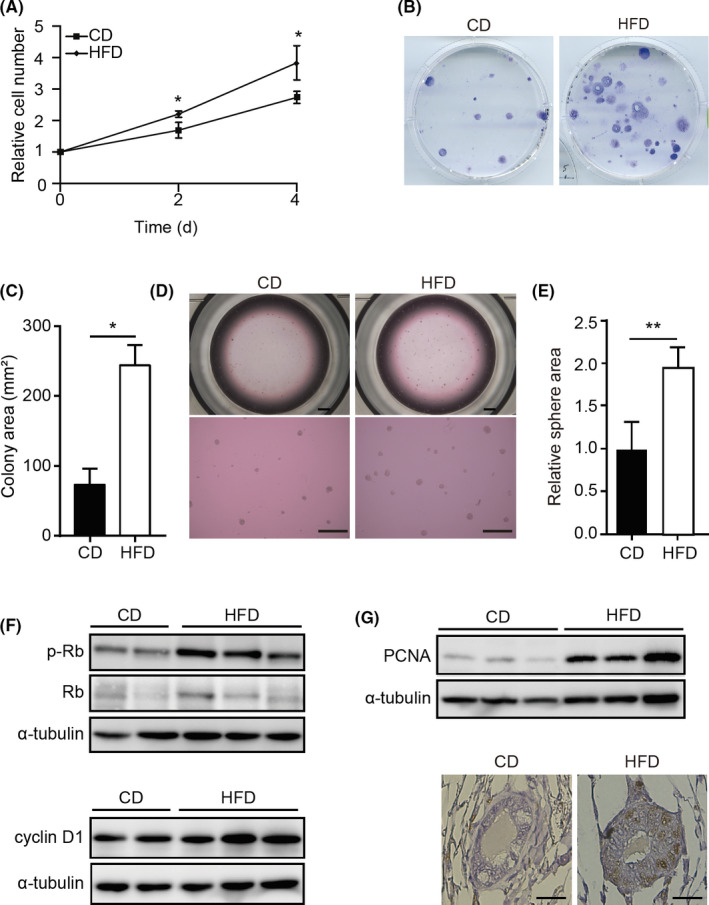

To identify the genes that could be responsible for mammary carcinogenesis stimulated by peripubertal high fat intake, we fed Trp53 −/− mice with HFD or CD for 5 weeks from the age of 3 weeks (Figure 1A). Diet composition is shown in Table S1. The HFD and CD contain equal calories. The HFD‐fed mice showed no significant difference in gain of body weight over the experimental period compared to CD‐fed mice (Figure 1B). We collected mammary gland tissues from these mice (Figure 1C), isolated MMECs according to previously published methods, 17 , 18 , 19 and cultured them under 2‐D conditions (Figure 1D). During culture, MMECs derived from HFD‐fed mice (HFD‐MMECs) were observed to proliferate significantly faster than MMECs derived from CD‐fed mice (CD‐MMECs) (Figure 2A). In addition, we found that HFD‐MMECs were more efficient in forming colonies (Figure 2B,C) and mammospheres (Figure 2D,E) than those in CD‐MMECs. We detected an elevated expression of p‐Rb and cyclin D1 in HFD (Figure 2F). Moreover, an increased PCNA expression was detected in MMECs and the mammary gland using IB and immunohistochemistry analysis, respectively, in HFD‐fed mice (Figure 2G). Thus, our results indicate that HFD promotes the proliferation of MMECs before mice gain obesity.

FIGURE 1.

Establishment of mouse mammary epithelial cells (MMECs). A, Schema of feeding of Trp53‐null mice with a high‐fat diet (HFD) or a control diet (CD) for 5 wk. Mice were killed at 8 wk and mammary glands were harvested. B, Body weight of the mice at the time of death (N = 7 for each group). C, Ventral view of abdominal (bottom) and thoracic (upper) mammary glands incised from either side of the mouse. D, MMECs cultured in serum‐free EpiCult‐B medium supplemented with recombinant human (rh) basic fibroblast growth factor, rh epidermal growth factor, heparin, and insulin. Images captured 24 h (left) and 72 h (right) after seeding. Scale bar = 200 µm. Data are mean ± SE. *P < .05 (Student’s t test) n.s., non‐significant

FIGURE 2.

High‐fat diet (HFD) stimulates growth of mouse mammary epithelial cells (MMECs). A, WST‐1‐based cell proliferation assay of MMECs derived from mice fed control diet (CD‐MMECs; N = 3) or HFD (HFD‐MMECs; N = 3) B, Colony formation assay of MMECs derived from mice fed with CD or HFD. C, Quantitative analysis of the colony area (N = 3 for each group). D, Mammosphere formation assay of CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs. Scale bar = 100 µm. E, Quantitative analysis of the sphere area (N = 3 for each group). F, Immunoblotting (IB) of indicated proteins in HFD‐MMECs and CD‐MMECs. Experiments were done in triplicate or duplicate. α‐Tubulin was used as a loading control. G, IB of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs (upper), a representative immunohistochemistry staining of PCNA in the mammary gland tissue in mice fed CD or HFD (bottom). Scale bar = 100 µm. Data are mean ± SE. *P < .05, **P < .01 (Student’s t test). p‐, phosphorylated; Rb, retinoblastoma protein

3.2. High‐fat diet alters expression of c‐Myc target genes

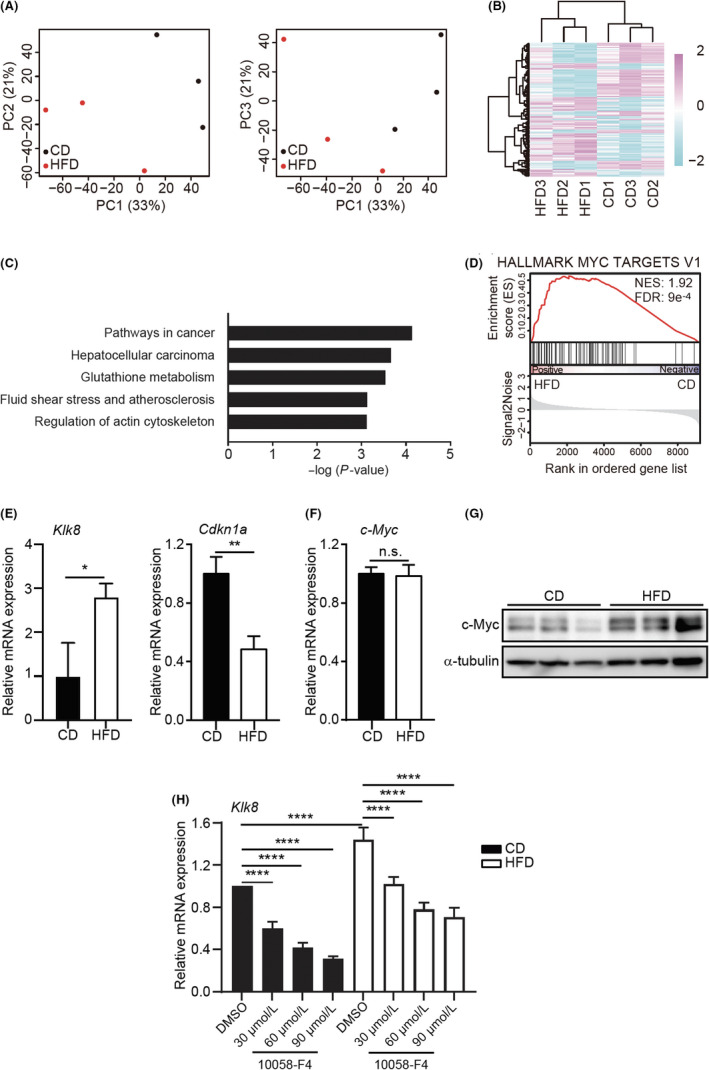

To investigate the molecular basis underlying the phenotypic changes in HFD‐MMECs, we analyzed the gene expression profile of HFD‐MMECs (N = 3) and CD‐MMECs (N = 3) using microarray analysis. Principal component analyses emphasized a significant difference between the gene expression of HFD‐MMECs and CD‐MMECs (Figure 3A). Moreover, an unbiased gene cluster analysis of top‐ranked upregulated or downregulated genes revealed that MMECs acquired distinct gene expression patterns following HFD exposure (N = 3) (Figure 3B and Table S2). We analyzed the top 100 genes upregulated in HFD‐MMECs compared to CD‐MMECs using Enrichr software and identified that networks related to “pathways in cancer” were enriched (Figure 3C and Table S3). Gene set enrichment analysis exhibited predefined gene sets related to cell cycle progression, cell proliferation (Figure S1A and Table S4), and c‐Myc target genes among upregulated genes in HFD (Figures 3D and S1B, Table S5).

FIGURE 3.

High‐fat diet (HFD) induces altered expression of the c‐Myc target genes and increases the c‐Myc protein level. A, Principal component (PC) analyses of gene expression profile in HFD‐mouse mammary epithelial cells (MMECs) (N = 3) and control diet (CD)‐MMECs (N = 3). B, Heat map of clustering analysis of top 100 up‐ or downregulated genes in HFD‐MMECs (N = 3) and CD‐MMECs (N = 3) by weighted average differentiation. C, Enrichr analysis of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways significantly (adjusted P < .05) enriched in the top 100 upregulated genes in HFD‐treated MMECs. D, Gene set enrichment of MYC signature (h.all.v7.0.symbols.gene.) in HFD‐MMECs vs CD‐MMECs. E, mRNA expression of indicated genes in CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs. F, mRNA expression of c‐Myc (N = 3). G, Immunoblotting of c‐Myc protein in CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs (N = 3). α‐Tubulin was used as a loading control. H, mRNA expression of Klk8 gene in CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs after treatment with Myc inhibitor 10058‐F4 or DMSO for 24 h in the indicated concentrations (N = 3 for each group). Data are mean ± SE, *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001 (Student’s t test and 2‐way ANOVA). FDR, false discovery rate; NES, net enrichment score; n.s., non‐significant

Next, we determined the relative mRNA expression of c‐Myc transcriptional targets Klk8 (a positive target) and Cdkn1a (a negative target) using RT‐qPCR. Results were found to be consistent with the microarray analysis (Figure 3E). Subsequently, we speculated that the altered expression of c‐Myc target genes was due to aberrant c‐Myc expression at the transcriptional or translational stage. Although we did not observe a distinct expression in the MYC proto‐oncogene family genes, c‐Myc (Figure 3F), Mycn, and Mycl (Figure S2), IB analysis detected a robust induction of c‐Myc expression in HFD (Figure 3G).

Furthermore, we ascertained whether the increased expression of c‐Myc target genes in the microarray analysis and subsequent RT‐qPCR is dependent on elevated c‐Myc protein levels detected in HFD. Here, we treated MMECs with a well‐established Myc inhibitor, 10058‐F4, that blocks c‐Myc activity by disrupting the dimerization of c‐Myc with its obligate partner molecule, Max. As Myc‐Max heterodimerization regulates c‐Myc transcriptional activity, the inhibitor blocks c‐Myc function. 27 , 28 Indeed, 10058‐F4 treatment suppressed the transcription of c‐Myc target genes (Figure 3H). Collectively, these data imply that HFD alters c‐Myc expression at the post‐translational process, in MMECs, and the anomalous c‐Myc activity influences the c‐Myc‐driven transcriptional regulation.

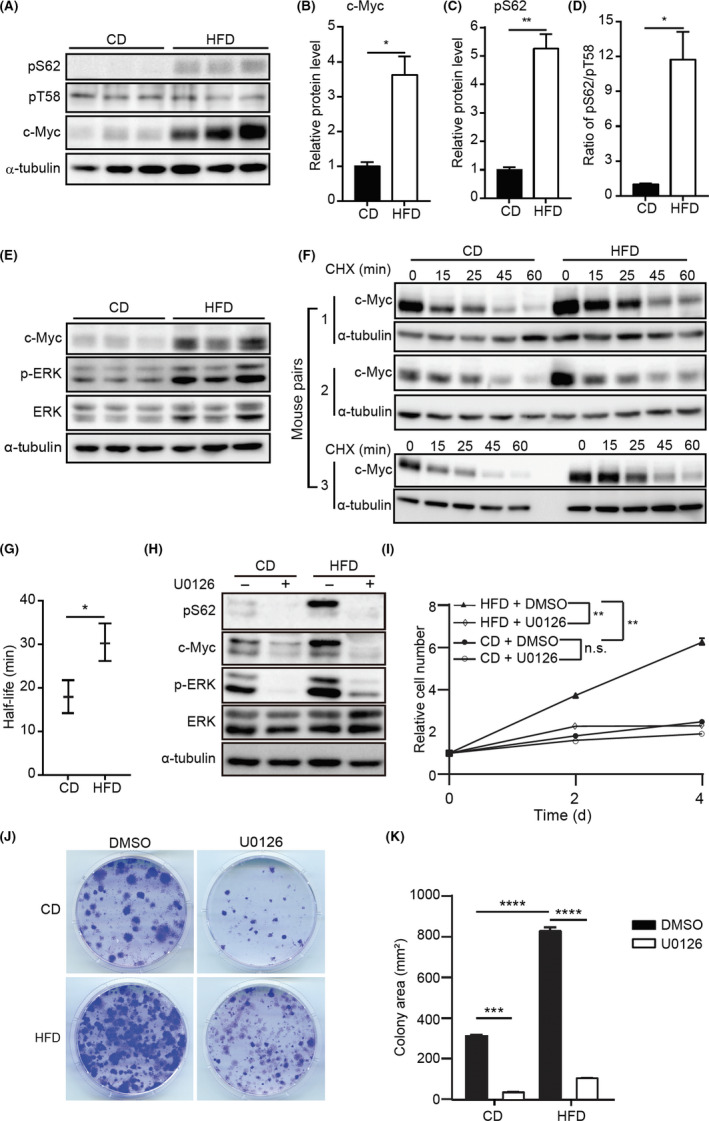

3.3. High‐fat diet stabilizes c‐Myc

We investigated the mechanism underlying the HFD‐mediated c‐Myc stabilization in MMECs. Two phosphorylation events occurring at serine 62 (S62) and threonine 58 (T58) are the key determinants for c‐Myc stability. 29 S62 and T58 phosphorylation govern the ubiquitination‐mediated proteasome degradation pathway of c‐Myc turnover. 30 c‐Myc phosphorylated at S62 (pS62) has widely been reported to activate its function to stimulate transcription of target genes. 31 Subsequently, c‐Myc is phosphorylated at T58 (pT58) by GSK‐3β and directed to be recognized by E3 ligase stem cell factor. 30 , 31

Notably, we detected an increased expression of c‐Myc pS62 in HFD‐MMECs with markedly upregulated c‐Myc levels. (Figure 4A‐C). Although c‐Myc pT58 expression was moderately changed between the 2 different diet groups (Figure 4A), the ratio of pS62 to pT58 c‐Myc expression was substantially higher in HFD‐MMECs (Figure 4D) compared to that in CD‐MMECs. c‐Myc stabilization primarily occurs through mitogenic activation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK axis. 32 Next, we analyzed the activity of ERK, which is the kinase responsible for c‐Myc phosphorylation at S62. Indeed, we observed enhanced ERK activity in HFD with concomitant induction of c‐Myc (Figure 4E). Although the pT58 level was slightly altered in HFD, we noticed a remarkable reduction of GSK‐3β expression between HFD‐MMECs and CD‐MMECs (Figure S3).

FIGURE 4.

High‐fat diet (HFD) stabilizes c‐Myc. A, Immunoblotting (IB) of c‐Myc phosphorylation at serine (S62) (pS62) and threonine (T58) (pT58) in control diet (CD)‐mouse mammary epithelial cells (MMECs) and HFD‐MMECs (N = 3). B, C, Quantitative analysis of expression of indicated proteins. D, Quantitative analysis of the pS62/pT58 using the IB data in (A). E, IB of indicated proteins in CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs (N = 3). F, Cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay to determine the half‐life of c‐Myc in CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs (N = 3). Cells were treated with 10 µg/mL CHX for the indicated time periods. G, Quantitative analysis of c‐Myc half‐life in CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs (N = 3). H, IB of indicated proteins in CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs in the presence of DMSO or nmol/L ERK inhibitor U0126 for 1 h. I, WST‐1‐based cell proliferation assay of CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs treated with DMSO or nmol/L U0126. Medium was replenished every 24 h (N = 3 for each group). J, Colony formation assay of CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs in the presence of DMSO or nmol/L U0126 for 14 days. Cell culture medium was replenished every 72 h. K, Quantitative analysis of the colony area in (J) (N = 3 for each group). α‐Tubulin was used as a loading control. ImageJ‐NIH software was used to quantify IB band intensities. Data are the mean ± SE. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001 (Student’s t test and 2‐way ANOVA) n.s., non‐significant

Furthermore, we determined the T1/2 of c‐Myc in 3 different mouse pairs using CHX chase assay using IB. The HFD‐MMECs showed a lower turnover rate of c‐Myc compared to that of CD‐MMECs (Figure 4F,G) which is consistent with the altered pS62/pT58. The IB band intensities obtained from the densitometric analysis are provided in Figure S4. Furthermore, on treating CD‐MMECs with a proteasomal inhibitor (MG‐132), a significant c‐Myc expression was detected in vitro (Figure S5), suggesting c‐Myc undergoes proteasome degradation in MMECs. These findings support the notion that HFD promotes c‐Myc stability due to enhanced ERK activity and augmented c‐Myc phosphorylation at S62.

To further explore whether the activated ERK is responsible for HFD‐driven upregulation of c‐Myc, we used an inhibitor for ERK, U0126. 33 The treatment antagonized the elevation of both pS62 and c‐Myc induced by HFD (Figure 4H). Moreover, U0126 exposure significantly antagonized the increased proliferation (Figure 4I) and colony formation of MMECs induced by HFD (Figure 4J,K).

To address whether the Trp53‐null background is necessary for the c‐Myc stabilization by HFD, we fed WT C57BL/6 mice with HFD or CD, as we did for Trp53 −/− mice. We could not detect a dramatic modification in c‐Myc activity in cultured MMECs derived from WT C57BL/6 mice fed either HFD or CD (data not shown). Moreover, WT MMECs failed to form colonies (data not shown). These findings suggest several possibilities, eg the HFD effect on c‐Myc stabilization is more evident in a Trp53‐null background, or immortalization might be necessary for the presentation of c‐Myc stabilization by HFD.

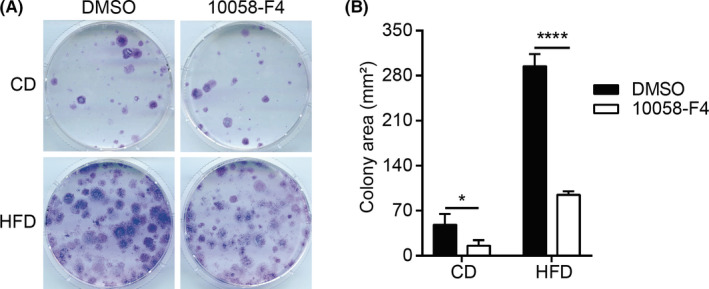

3.4. High‐fat diet stimulates MMECs to form colonies in a c‐Myc‐dependent manner

Next, we evaluated whether the increased colony‐forming potential in HFD‐MMECs (Figure 2B) is due to the enhanced c‐Myc activity, by undertaking colony‐forming assays in the presence of the Myc inhibitor 10058‐F4. The 10058‐F4 treatment significantly antagonized the elevated clonogenic activity in HFD‐MMECs. These data suggest that c‐Myc is responsible for the enhanced clonogenic activity in HFD (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

High‐fat diet (HFD) stimulates mouse mammary epithelial cells (MMECs) to form colonies in a c‐Myc‐dependent manner. A, Colony formation assay of control diet (CD)‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs treated with or 60 µmol/L c‐Myc inhibitor 10058‐F4 (N = 3). Cells (4 × 103) were seeded on day 0 onto 60‐mm dishes and stained with crystal violet on day 14. B, Quantitative analysis of the average colony area in (A). Data are mean ± SE *P < .05, ****P < .0001 (2‐way ANOVA)

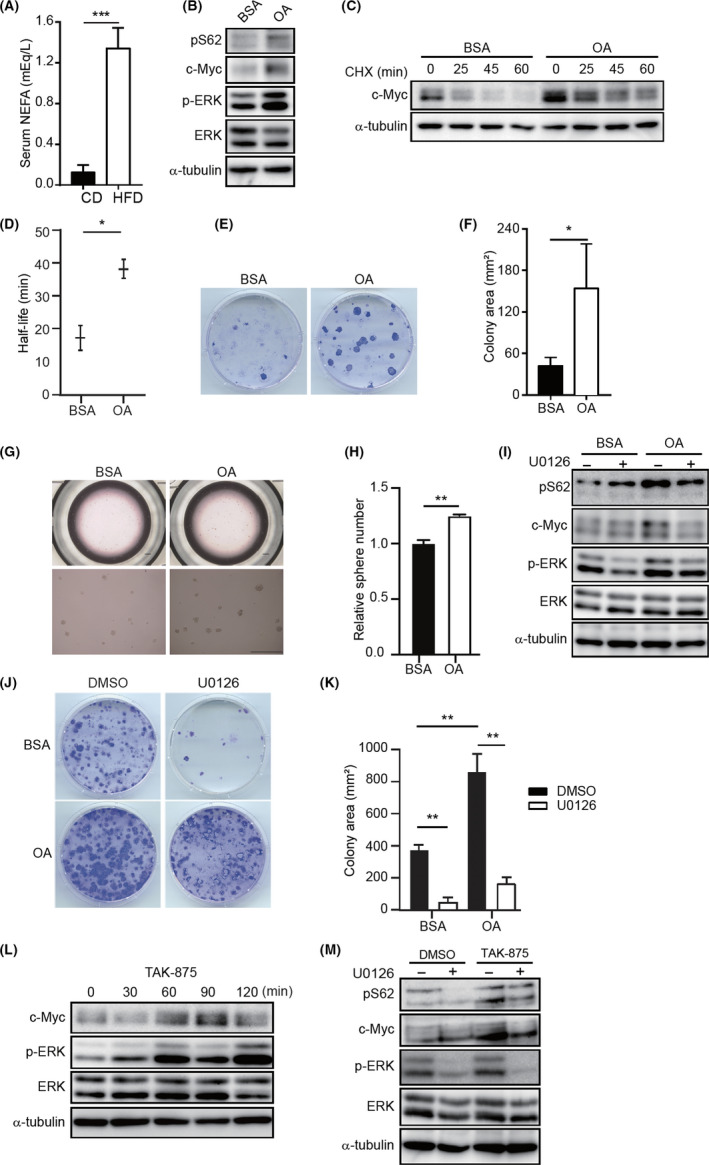

3.5. Oleic acid stabilizes c‐Myc in MMECs

As fatty acid is one of the major constituents of HFD (Table S6), we postulated that the circulating FFA level might be elevated in mice with high fat intake. Moreover, HFD‐derived serum FFA could be a dietary factor that generates a tremendous influence on MMECs. As expected, FFA was found to be elevated in HFD‐fed mice (Figure 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Oleic acid (OA) stabilizes c‐Myc in mouse mammary epithelial cells (MMECs). A, Serum nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) concentration in mice fed with control diet (CD) or high‐fat diet (HFD) for 5 weeks (N = 3). B, Immunoblotting (IB) of indicated proteins in CD‐MMECs treated with BSA or 0.15 mmol/L BSA‐conjugated OA for 48 h (N = 4). C, Cycloheximide (CHX) assay of CD‐MMECs treated with BSA or 0.15 mmol/L BSA‐conjugated OA for 48 h followed by 10 µg/mL CHX treatment for the indicated time periods (N = 3). D, Quantitative analysis of c‐Myc half‐life in CD‐MMECs and HFD‐MMECs (N = 3). E, Colony formation assay of CD‐MMECs (N = 3). Cells were treated with BSA or 0.15 mmol/L BSA‐conjugated OA . Cells (4 × 103) were seeded on day 0 onto 60‐mm dishes and stained with crystal violet on day 14. F, Quantitative analysis of the colony area in (E). G, Mammosphere formation assay of CD‐MMECs treated with BSA or 0.15 mmol/L BSA‐conjugated OA (N = 3). H, Quantitative analysis of the sphere number in (G). Scale bar = 100 µm (upper), 200 µm (bottom). I, IB of indicated proteins in CD‐MMECs treated with BSA or 0.15 mmol/L BSA‐conjugated OA followed by treatment with DMSO or 50 nmol/L U0126 for 1 h. J, Colony formation assay of CD‐MMECs treated with BSA or 0.15 mmol/L BSA‐conjugated OA for 10 days and then with DMSO or 50 nmol/L U0126 for additional 7 days. Cells (6 × 103) were seeded on day 0 onto 60‐mm dishes and stained with crystal violet on day 14 (N = 3 for each group). Cell culture medium was replenished every 72 h. K, Quantitative analysis of the colony area in (J) (N = 3 each group). L, IB of indicated proteins in CD‐MMECs treated with DMSO or 100 nmol/L TAK‐875 (G protein‐coupled receptor [GPR40] agonist) for indicated time periods. M, IB of indicated proteins in CD‐MMECs treated with DMSO or 100 nmol/L GPR40 agonist TAK‐875 for 24 h and then with DMSO or 50 nmol/L U0126 for additional 1 h. α‐Tubulin was used as a loading control. Cells were cultured in serum‐free complete EpiCult‐B medium supplemented with recombinant human (rh) basic fibroblast growth factor, rh epidermal growth factor, heparin, and insulin. Data are mean ± SE, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 (Student’s t test and 2‐way ANOVA)

To further investigate the effect of FFA, we treated MMECs with OA, which is a major fatty acid constituent of the HFD. We cultured CD‐MMECs in serum‐free media for 24 hours and then treated with 30 µmol/L OA for an additional 48 hours. Immunoblotting analysis revealed a dramatically enhanced expression of total c‐Myc and c‐Myc pS62 in OA‐treated MMECs compared to their expression in control cells (Figure 6B). Moreover, we observed extended T1/2 of c‐Myc in CD‐MMECs when treated with OA (Figure 6C,D). Additionally, we found higher clonogenic and spherogenic activity in MMECs after treatment with OA (Figure 6E‐H). These data indicate that serum fatty acid contributes to attenuated c‐Myc degradation.

We addressed whether the activated ERK is directly responsible for the OA‐induced c‐Myc stability as we observed in HFD. We analyzed the effect of U0126 on OA‐mediated induction of c‐Myc and p‐Myc (S62). Indeed, U0126 abrogated the enhanced c‐Myc and p‐Myc (S62) activity induced by OA treatment (Figure 6I). Consistently, U0126 suppressed the augmented colony formation induced by OA (Figure 6J,K).

To corroborate further that the OA promotes mitogenic signals to activate c‐Myc, we treated MMECs with TAK‐875, a GPR40 agonist. G protein‐coupled receptor 40 is recognized as a target of medium‐ to long‐chain fatty acids, such as OA, to generate mitogenic signaling through the Gpr40‐Mek‐Erk axis. 34 We found markedly elevated c‐Myc expression in MMECs on TAK‐875 exposure in a time‐dependent manner (Figure 6L). Additionally, we treated CD‐MMECs with TAK‐875 for 24 hours then with the ERK inhibitor U0126. This revealed that the pS62 expression and c‐Myc protein expression increased following TAK‐875 exposure was significantly antagonized when the p‐ERK expression was decreased (Figure 6M).

We used MCF10A, a nonmalignant immortalized human mammary epithelial cell line, to investigate whether OA gives rise to a similar effect observed in human MMECs. Both OA and TAK‐875 augmented p‐Myc (S62) and c‐Myc levels (Figure S6) in MCF10A. As PA is one of the most abundant saturated fatty acids in serum, we attempted to reveal the influence of PA on c‐Myc stability. We observed a substantial increase of c‐Myc and p‐Myc (S62) in MMECs and MCF10A cells that were exposed to PA at lower concentrations (25‐50 µmol/L). However, PA at higher concentrations (100‐200 µmol/L) decreased c‐Myc levels in MCF10A cells (Figure S7). Importantly, the PA‐driven c‐Myc induction was attained without p‐ERK elevation (Figure S7). These findings suggest that PA might induce c‐Myc at relatively low concentrations through an alternative pathway. Additionally, OA but not PA reduced GSK‐3β in MMECs and MCF10A cells (Figure S8). Overall, our findings indicate that HFD contributes to breast carcinogenesis in part by extending c‐Myc stability through fatty acid‐induced stimulation of mitogenic signaling.

4. DISCUSSION

Despite many studies reporting the crucial influence of HFD on mammary tumor initiation and promotion, 7 , 8 , 9 , 11 the mechanistic insight remains elusive. In the present study, we have determined that HFD intake during the peripubertal period has a remarkable impact on Trp53 −/− MMECs through the stabilization of c‐Myc oncoprotein.

c‐Myc is known to be expressed at a higher level in the majority of human malignancies, including breast cancer. 29 , 35 , 36 Many mouse models have revealed the critical role of c‐Myc in initiating and promoting a wide variety of tumors. 29 , 37 Conventionally, c‐Myc is known to be activated due to gene amplification, increased mRNA expression, or enhanced protein stability. 29 , 35 , 38 c‐Myc stability is regulated by phosphorylation events. Initially, c‐Myc is phosphorylated at S62 residue by ERK, which improves protein stability and facilitates c‐Myc to activate transcription of the target genes. 29 , 35 , 36 Subsequent phosphorylation at T58 residue by GSK‐3β directs the protein to ubiquitination and proteasome‐mediated degradation. 30 , 39 In malignancies, c‐Myc activity is increased due to its aberrant phosphorylation status, which is attained by deregulation of mitogenic signals. Our study shows that HFD has the potential to augment c‐Myc S62 phosphorylation and to decrease GSK‐3β activity, which enables c‐Myc to gain extra stability. In normal cells, c‐Myc expression is strictly regulated, and T1/2 of c‐Myc is typically reported to be 20‐30 minutes. 39 , 40 In the present study, T1/2 of c‐Myc in CD‐MMECs was found to be 18 minutes, whereas it was extended to 30 minutes in HFD‐MMECs.

Malignantly transformed cells, including breast cancer cells, utilize FFAs to mediate proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 Oleic acid is one of the long‐chain fatty acids and a major fatty acid constituent of the HFD. We found increased serum concentration of FFAs, including OA, in HFD‐fed mice (Figure 6A). Serum fatty acid concentration has already been recognized as a valuable clinical parameter in breast cancer patients. 46 , 47 In particular, OA acts as an endogenous ligand for several types of receptors such as a class of GPRs known as FFARs to perform its diverse functions. 48 , 49 Both FFAR1/GPR40 and FFAR4/GPR120 are primarily activated by long‐chain fatty acids such as OA. 41 , 43 , 50 These receptors are predominantly expressed in breast cancer and noncancerous mammary epithelial cell lines and reported to mediate cell proliferation. 41 Moreover, it has been proposed that OA induces ERK1/2 activity and subsequently stimulates the proliferation of breast cancer cell lines such as MCF‐7 and MDA‐MB‐231. 43 Our present study together with the previous findings in breast cancer cell lines indicate that serum OA could play a pivotal role in the prediction of breast cancers.

In conclusion, we here identified that HFD influences MMECs by stabilizing an oncoprotein, pointing to a novel mechanism underlying mammary carcinogenesis enhanced by dietary fat. We also propose that fat intake should be restricted during the peripubertal period to lower the breast cancer risk in later life. This study can be extended to accelerated stages of mammary gland development such as pregnancy and breastfeeding. Additionally, we suggest the possibility of using fatty acid receptor antagonists to preventor treat breast cancer.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Supporting information

Fig S1‐S8

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5

Table S6

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Funding Program for Next Generation World‐Leading Researchers (LS049), Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (15H01487 and 17H05615), and Grants‐in‐Aid for Scientific Research (17H03576, 17K19586, 19K22555, and 20H03509), and AMED‐CREST (20gm0910003h0206). NK thanks the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) scholarship program for support. S. Kumar was supported by an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (GNT1103006).

Kulathunga N, Kohno S, Linn P, et al. Peripubertal high‐fat diet promotes c‐Myc stabilization in mammary gland epithelium. Cancer Sci. 2020;111:2336–2348. 10.1111/cas.14492

REFERENCES

- 1. Boyd NF, Stone J, Vogt KN, Connelly BS, Martin LJ, Minkin S. Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: A meta‐analysis of the published literature. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(9):1672‐1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thiebaut ACM, Kipnis V, Chang S‐C, et al. Dietary fat and postmenopausal invasive breast cancer in the national institutes of health‐AARP Diet and Health Study Cohort. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(6):451‐462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sieri S, Krogh V, Ferrari P, et al. Dietary fat and breast cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(5):1304‐1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martinez‐Chacin RC, Keniry M, Dearth RK. Analysis of high fat diet induced genes during mammary gland development: identifying role players in poor prognosis of breast cancer. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sieri S, Chiodini P, Agnoli C, et al. Dietary fat intake and development of specific breast cancer subtypes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(5):68 10.1093/jnci/dju068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nguyen NM, de Oliveira AF, Jin L, et al. Maternal intake of high n‐6 polyunsaturated fatty acid diet during pregnancy causes transgenerational increase in mammary cancer risk in mice. Breast Cancer Res. 2017;19(1):1‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao Y, Tan YS, Aupperlee MD, et al. Pubertal high fat diet: effects on mammary cancer development. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(5):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aupperlee MD, Zhao Y, Tan YS, et al. Puberty‐specific promotion of mammary tumorigenesis by a high animal fat diet. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1):1‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu Y, Aupperlee MD, Zhao Y, et al. Pubertal and adult windows of susceptibility to a high animal fat diet in Trp53‐null mammary tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7(50):83409‐83423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Olson LK, Tan Y, Zhao Y, Aupperlee MD, Haslam SZ. Pubertal exposure to high fat diet causes mouse strain‐dependent alterations in mammary gland development and estrogen responsiveness. Int J Obes. 2010;34(9):1415‐1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhu Y, Aupperlee MD, Haslam SZ, Schwartz RC. Pubertally initiated high‐fat diet promotes mammary tumorigenesis in obesity‐prone FVB mice similarly to obesity‐resistant BALB/c mice. Transl Oncol. 2017;10(6):928‐935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bertheau P, Lehmann‐Che J, Varna M, et al. P53 in breast cancer subtypes and new insights into response to chemotherapy. Breast. 2013;22:S27‐S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hursting SD, Perkins SN, Phang JM, Barrett JC. Diet and cancer prevention studies in p53‐deficient mice. J Nutr. 2001;131(11):3092S‐3094S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holen I, Speirs V, Morrissey B, Blyth K. In vivo models in breast cancer research: progress, challenges and future directions. Dis Model Mech. 2017; 10:359‐371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tsukada T, Tomooka Y, Takai S, et al. Enhanced proliferative potential in culture of cells from p53‐deficient mice. Oncogene 1993;8(12):3313‐3322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salah M, Nishimoto Y, Kohno S, et al. An in vitro system to characterize prostate cancer progression identified signaling required for self‐renewal. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55(12):1974‐1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stingl J, Eirew P, Ricketson I, et al. Purification and unique properties of mammary epithelial stem cells. Nature. 2006;439(7079):993‐997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karantza‐Wadsworth V, White E. Chapter 4 A mouse mammary epithelial cell model to identify molecular mechanisms regulating breast cancer progression. Methods Enzymol. 2008;446:61‐76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fujiwara T, Bandi M, Nitta M, Ivanova EV, Bronson RT, Pellman D. Cytokinesis failure generating tetraploids promotes tumorigenesis in p53‐null cells. Nature. 2005;437(7061):1043‐1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kadota K, Nakai Y, Shimizu K. A weighted average difference method for detecting differentially expressed genes from microarray data. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2008;3(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, et al. Interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14(1):128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W90‐W97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge‐based approach for interpreting genome‐wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545‐15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kitajima S, Kohno S, Kondoh A, et al. Undifferentiated state induced by Rb‐p53 double inactivation in mouse thyroid neuroendocrine cells and embryonic fibroblasts. Stem Cells. 2015;33(5):1657‐1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Muranaka H, Hayashi A, Minami K, et al. A distinct function of the retinoblastoma protein in the control of lipid composition identified by lipidomic profiling. Oncogenesis. 2017;6(6):e350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pike LS, Smift AL, Croteau NJ, Ferrick DA, Wu M. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation by etomoxir impairs NADPH production and increases reactive oxygen species resulting in ATP depletion and cell death in human glioblastoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta ‐ Bioenerg. 2011;1807(6):726‐734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yin X, Giap C, Lazo JS, Prochownik EV. Low molecular weight inhibitors of Myc‐Max interaction and function. Oncogene. 2003;22(40):6151‐6159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guo J, Parise RA, Joseph E, et al. Efficacy, pharmacokinetics, tisssue distribution, and metabolism of the Myc‐Max disruptor, 10058–F4 [Z, E]‐5‐[4‐ethylbenzylidine]‐2‐thioxothiazolidin‐4‐ one, in mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63(4):615‐625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang X, Farrell AS, Daniel CJ, et al. Mechanistic insight into Myc stabilization in breast cancer involving aberrant Axin1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(8):2790‐2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Welcker M, Orian A, Jin J, et al.The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation‐dependent c‐Myc protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101(24):9085–9090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Farrell AS, Sears RC. MYC degradation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(3):a014365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bachireddy P, Bendapudi PK, Felsher DW. Getting at MYC through RAS. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(12):4278‐4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang C, Zhang S, Liu J, Xu S, Fu Y. Secreted pyruvate kinase M2 promotes lung cancer metastasis through activating the integrin Beta1/FAK Signaling. Pathway. 2020;30:1780‐1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miyamoto J, Mizukure T, Park SB, et al. A gut microbial metabolite of linoleic acid, 10‐hydroxy‐cis‐12‐octadecenoic acid, ameliorates intestinal epithelial barrier impairment partially via GPR40‐MEK‐ERK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(5):2902‐2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang X, Cunningham M, Zhang X, et al. Phosphorylation regulates c‐Myc’s oncogenic activity in the mammary gland. Cancer Res. 2011;71(3):925‐936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang C, Zhang S, Zhang Z, He J, Xu Y, Liu S. ROCK has a crucial role in regulating prostate tumor growth through interaction with c‐Myc. Oncogene. 2014;33(49):5582‐5591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen H, Liu H, Qing G. Targeting oncogenic Myc as a strategy for cancer treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2018;3(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu J, Chen Y, Olopade OI. MYC and breast cancer. Genes Cancer. 2010;1(6):629‐640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hann SR. Role of post‐translational modifications in regulating c‐Myc proteolysis, transcriptional activity and biological function. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16(4):288‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clark EA, Shu GL, Lüscher B, et al. Activation of human B cells. Comparison of the signal transduced by IL‐4 to four different competence signals. J Immunol. 1989;143(12):3873‐3880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marcial‐Medina C, Ordoñez‐Moreno A, Gonzalez‐Reyes C, Cortes‐Reynosa P, Salazar EP. Oleic acid induces migration through a FFAR1/4, EGFR and AKT‐dependent pathway in breast cancer cells. Endocr Connect. 2019;8(3):252‐265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhao J, Zhi Z, Wang C, et al. Exogenous lipids promote the growth of breast cancer cells via CD36. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(4):2105‐2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Soto‐Guzman A, Robledo T, Lopez‐Perez M, Salazar EP. Oleic acid induces ERK1/2 activation and AP‐1 DNA binding activity through a mechanism involving Src kinase and EGFR transactivation in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;294(1–2):81‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Navarro‐Tito N, Soto‐Guzman A, Castro‐Sanchez L, Martinez‐Orozco R, Salazar EP. Oleic acid promotes migration on MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells through an arachidonic acid‐dependent pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42(2):306‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li S, Zhou T, Li C, et al. High metastaticgastric and breast cancer cells consume oleic acid in an AMPK dependent manner. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Madak‐Erdogan Z, Band S, Zhao YC, et al. Free fatty acids rewire cancer metabolism in obesity‐associated breast cancer via estrogen receptor and mTOR signaling. Cancer Res. 2019;79(10):2494‐2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Byon CH, Hardy RW, Ren C, et al. Free fatty acids enhance breast cancer cell migration through plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 and SMAD4. Lab Investig. 2009;89(11):1221‐1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Falomir‐Lockhart LJ, Cavazzutti GF, Giménez E, Toscani AM. Fatty acid signaling mechanisms in neural cells: fatty acid receptors. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019;13:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McArthur MJ, Atshaves BP, Frolov A, Foxworth WD, Kier AB, Schroeder F. Cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of long chain fatty acids. J Lipid Res. 1999;40(8):1371‐1383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang X, He S, Gu Y, et al. Fatty acid receptor GPR120 promotes breast cancer chemoresistance by upregulating ABC transporters expression and fatty acid synthesis. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:251‐262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1‐S8

Table S1

Table S2

Table S3

Table S4

Table S5

Table S6