Abstract

Hard-rock mining for metals, such as gold, silver, copper, zinc, iron and others, is recognized to have a significant impact on the environmental media, soil and water, in particular. Toxic contaminants released from mine waste to surface water and groundwater is the primary concern, but human exposure to soil contaminants either directly, via inhalation of airborne dust particles, or indirectly, via food chain (ingestion of animal products and/or vegetables grown in contaminated areas), is also, significant. In this research, we analyzed data collected in 2007, as part of a larger environmental study performed in the Rosia Montana area in Transylvania, to provide the Romanian governmental authorities with data on the levels of metal contamination in environmental media from this historical mining area. The data were also considered in policy decision to address mining-related environmental concerns in the area. We examined soil and water data collected from residential areas near the mining sites to determine relationships among metals analyzed in these different environmental media, using the correlation procedure in the SAS statistical software. Results for residential soil and water analysis indicate that the average values for arsenic (As) (85 mg/kg), cadmium (Cd) (3.2 mg/kg), mercury (Hg) (2.3 mg/kg) and lead (Pb) (92 mg/kg) exceeded the Romanian regulatory exposure levels [the intervention thresholds for residential soil in case of As (25 mg/kg) and Hg (2 mg/kg), and the alert thresholds in case of Pb (50 mg/kg) and Cd (3 mg/kg)]. Average metal concentrations in drinking water did not exceed the maximum contaminant level (MCL) imposed by the Romanian legislation, but high metal concentrations were found in surface water from Rosia creek, downstream from the former mining area.

Keywords: metal contamination, mining, soil, water

Introduction

Rosia Montana is a former mining area in the Apuseni Mountains (part of the Western Romanian Carpathians), belonging to the Golden Quadrilateral, one of the most important gold-producing areas in Europe. The volcanogenic complex from Rosia Montana is considered as a maar-diatreme structure, mainly consisting of clastic rocks created by successive phases of volcanic activity (1). The occasional contact between the ascending magma and the shallow aquifers has produced a large pile of phreatomagmatic breccias. Two main dacitic bodies, locally affected by hydrothermal alterations, initiated the mineralization process. The geological processes in the past times provided Rosia Montana with ores rich in metals, such as silver and gold, which have been mined since the Roman times. Ore extraction/processing and disposal of the mining tailings are the most common mining operations leading to the contamination of the environment (2), particularly the contamination of water, soil and vegetation/crops grown in and around the mining areas (3, 4). Contaminants of concern in the residential areas near the former mining sites include metalloids and heavy metals [arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), mercury (Hg), nickel (Ni), lead (Pb)] found in soil and dust, which are deposited on the vegetation (including crops) and/or in the water bodies, as a result of leaching from the mine tailings and rocks, due to the acid mine drainage aggressive action (5). These contaminants might pose health risks to population groups living in surroundings of the mining areas (4), as the metals in the environmental media (air, soil, water, crops) may enter the human body via inhalation of airborne particles, ingestion of water and/or food, inadvertent ingestion of soil and dermal contact with soil and/or water (6). Some of these metalloids and heavy metals may bioaccumulate in the body causing a number of adverse health effects, including cancer (7–10).

As part of a larger investigation, we have conducted a study to evaluate the distribution of metals and levels of exposure in the residential areas located near the former mining sites in Rosia Montana, and to investigate the pathways through which the contaminants are entering the residential areas.

Methods

Study area

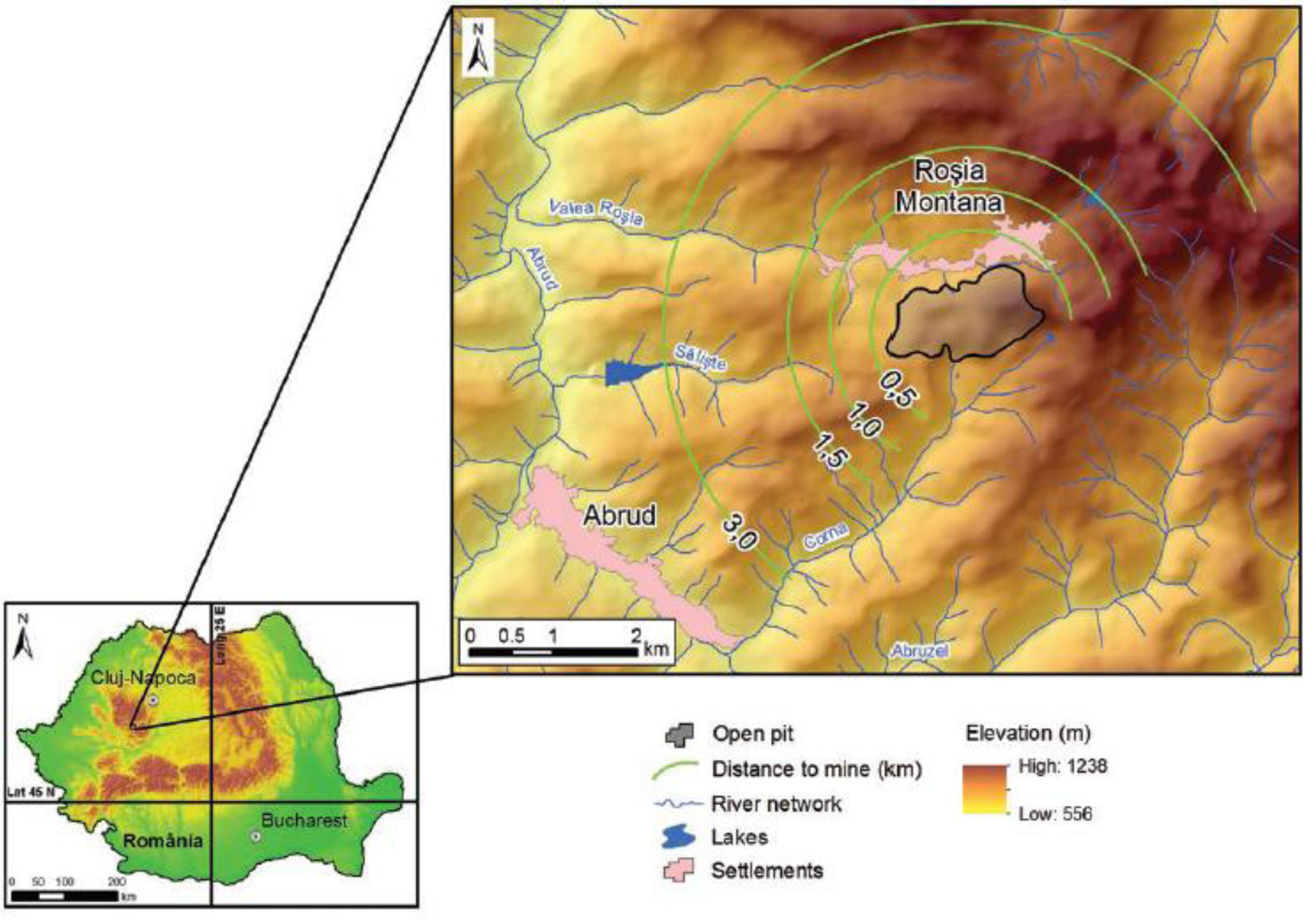

Our study area is a former mining area in the Apuseni Mountains on the administrative territory of Alba County, hosting 2656 inhabitants in Rosia Montana Commune (according to 2011 Romanian governmental census), located within the area of the Rosia stream springs, which eventually flow into the Abrud River and then into the Aries River (Figure 1). The relief of this area is dominated by hills and valleys, with elevations above 1000 m in the massifs (Carnic, Cetate and Orlea) and lower elevations in Rosia Montana basin (550–580 m above mean sea level). The area has a temperate continental climate, with an annual average temperature of 5.5 °C and an annual precipitation between 600 and 996 mm (multi-annual average of 795 mm) (11).

Figure 1:

Rosia Montana area.

Soil sampling and chemical analysis

We collected and analyzed 84 soil samples from a residential area located in the surroundings of a former mining area that included around 600 inhabitants and not more than 300 inhabited dwellings, at only a single time point, in 2007. Residential soil samples in Rosia Montana area were collected from the yards of the houses and placed in metal-free polyethylene containers. A clean stainless steel shovel was used to collect the samples from the topsoil layer (0–5 cm depth). After collection, samples were labeled, sealed and transported to the laboratory where they were stored indoors until analysis. Fifty-gram aliquots of each residential soil sample were then analyzed using X-ray fluorescence (NITON XL 700, Niton Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA), according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) 6200 method. Also, soil samples (composite samples) were collected from mining pits and metals were analyzed using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry [data provided by Rosia Montana Gold Corporation (RMGC)].

Water sampling and analysis:

Drinking water samples were collected from springs and wells in the area, in 250 mL containers and were stored on ice during transportation to the lab, and then, at 4 °C, until analysis. Immediately after collection, the water samples were acidified with 2.5 mL concentrated nitric acid. Metals in water samples were analyzed using atomic absorption spectrometry with hydride generation (AAS-HG, VARIO 6®HydroEA, Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) for As, graphite furnace (AAS-GP, VARIO 6®EA, Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) for Pb, Cd, Cr, Ni and cold vapors hydride generation (AAS-CVHG, VARIO 6®HydrHg, Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) for Hg. The data on metal concentrations in water were extracted from the Environmental Impact Assessment Study – Water Baseline Report and Surface Water Quality, submitted to the Romanian Ministry of Environment by RMGC (12, 13).

Data analysis:

We used the SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) for the statistical analysis. We investigated metal distributions in the environmental media (soil and water) collected from the residential area in the surroundings of the mining sites, using the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) procedure. The continuous response/dependent variables in the analysis were soil and water metal concentrations (results of 84 soil samples and 21 groundwater samples). The classification/independent variables were town and street. The primary assumption in this analysis was that the variation in environmental media results were due to the effect of location (town and street). Random error was assumed to account for the remaining variation. Results were used to determine if there was an effect of distance from Cetate Pit (the central mining area in Rosia Montana) on concentrations of metals in soil and water. Significant difference was indicated by p-values ≤ 0.05.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 show the average values and standard deviations (SDs) for the metal concentrations in composite soil samples from mine pits and residential areas, surface water from the streams and drinking water collected from springs and wells. In residential soil, the average levels of As and Hg exceeded the Romanian regulatory levels. More precisely, the intervention thresholds (IT) for residential soil (IT for As = 25 mg/kg and IT for Hg = 2 mg/kg) and the average levels of Pb and Cd exceeded the alert thresholds (AT) for residential soil (AT = 50 mg/kg for Pb and AT = 3 mg/kg for Cd) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Levels of contaminants of concern in soil, in Rosia Montana (RM) area, and Romanian regulatory exposure levels for metals in residential soil (mg/kg or ppm) – alert thresholds (AT) and intervention thresholds (IT) for residential soil.

| Pb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | Mine Pit (n=7) | 114.4±17.7 | <8a | 22.1±3 | - | 39 | 104.4±106.3 |

| Residential (n=84) | 85±51 | 3.2±5.9 | 41±43 | 2.3±2.8 | 20±19 | 92±51 | |

| Romanian Regulatory Exposure Levels for metals (residential soil) - AT / IT | 15/25 | 3/5 | 100/300 | 1/2 | 75/150 | 50/100 | |

Contaminants of concern concentrations (COCs) in mg/kg (ppm) for soil (average ± SD).

Limit of detection (LOD). Bold value indicates Romanian regulatory exposure levels AT/IT.

“–” no data.

Table 2:

Levels of contaminants of concern in water, in Rosia Montana (RM) area, and Romanian regulatory exposure levels for metals in drinking water (μg/L) – maximum contaminant level (MCL) in drinking water.

| Pb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Stream | ||||||

| 2005 | Upstream from RM mining area (n=3) | 1.5±0.9 | <1a | 4.8 | - | 1.8 | <1a |

| 2005 | Downstream from RM mining area (n=3) | 17±14.5 | 6±7.2 | 44.9±3.6 | - | 72.4±58.7 | <1a |

| 2006 | Upstream from RM mining area (n=3) | 2.7±3.5 | <1a | 2.2±1.3 | - | <1a | <1a |

| 2006 | Downstream from RM mining area (n=2) | 22.8±27.1 | 29.1±39.4 | 20.2±12.4 | - | 121±143.5 | 22.5 |

| 2007 | Upstream from RM mining area (n=2) | 2.1±0.3 | <1a | 3.5 | - | <1a | <1a |

| 2007 | Downstream from RM mining area (n=0) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2008 | Upstream from RM mining area (n=1) | <0.05a | <1a | <1a | - | <1* | <1a |

| 2008 | Downstream from RM mining area (n=1) | 294 | 95.3 | 57.1 | - | 93.6 | 23.8 |

| Water | Drinking (n=10) | 5.4±3.1 | 2.1±0.3 | 4.2±1.5 | - | 5.4±3.1 | 1.7±1.9 |

| Romanian Regulatory Exposure Levels for metals (Drinking water) - MCL | 10 | 5 | 50 | 1 | 20 | 10 | |

Contaminants of concern concentrations (COCs) in μg/L for water (average ± SD).

Limit of detection (LOD). Bold value indicates Romanian regulatory exposure levels MCL.

“–” no data.

Metal concentrations in Rosia creek showed fluctuations over time, with higher average levels downstream compared to upstream from the mining impacted areas (Table 2). For the early part of this dataset, mining activities were being conducted (2005 until early 2006). From that time forward, the metal concentrations generally increased in the surface waters, probably because the water treatment system required for operating the mining activities was deactivated when mining operations ceased. The difference in metal average levels upstream and downstream from the mining area (higher levels downstream as compared to upstream), illustrates the contribution of the mining process to the contamination of the stream. However, the average metal concentrations in drinking water collected from five springs and five wells in the area did not exceed the maximum contaminant level (MCL) imposed by the Romanian legislation (Table 2).

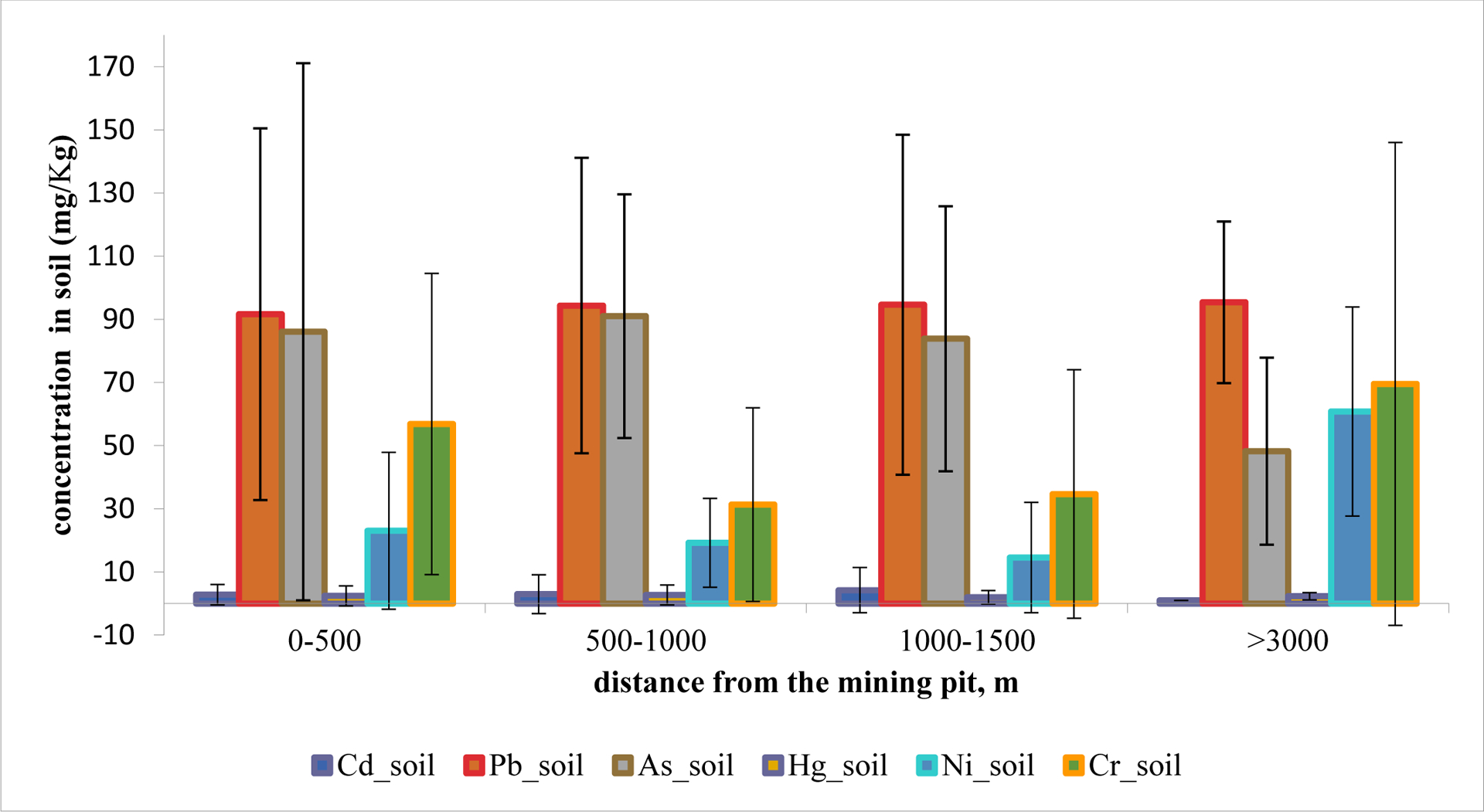

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the average metal concentrations and SDs with the distance from the mining area (Cetate Pit). The average concentration values do not seem to decrease further from the pit.

Figure 2:

Average and SDs for metals concentrations (mg/kg or ppm) measured in n = 84 soil samples from residential areas near the former mine, by distance from the mining pit.

The ANOVA results for soil and water metals concentration by distance from the Cetate Pit indicate that the distance from the pit influences specific environmental media results. The metal concentrations in environmental media were influenced by the distance from the Cetate Pit in case of As in water and Pb in soil and water (data not shown). For the other metals, As, Cr, Ni, Cd and Hg in soil, the concentrations in the environmental media were not influenced by the distance from the pit, and were generally well above background levels seen at non-mining locations.

Discussion

We determined the metal concentrations in the environmental media and evaluated their distribution within the residential areas located near the former mining sites. We found metals (As, Hg) in residential soil in concentrations that exceeded the Romanian regulatory exposure levels (the IT level) for residential soil, but no contaminant of concern exceeded the MCL for the water sources employed as drinking water sources in the residential area near the former mine, while the quality of the surface waters was dramatically changed by the historical contamination sources (former mine acid drainage), as reflected by the higher concentrations of contaminants downstream from mining area, compared to upstream concentrations.

The statistical analysis of our data indicated that metal contamination in soil is widespread in the residential areas near the former mining sites in Rosia Montana, and that the distance from the mining pit (Cetate Pit) does influence the metal contamination in the investigated environmental media (soil and water), but the effect of distance from the mining pit is limited. Thus, distance from the pit was found to only affect two metals of concern: As in water and Pb in soil and water.

Other similar studies conducted in Rosia Montana area have shown that Ni and Cr levels in topsoil do not seem to be related to the rocks accommodating the gold mineralization (5).

As regards the geology of the area, in the main part of Rosia Montana village, the geological structure consists of volcanic rocks belonging to different types of andesites and andesitic/dacitic breccias. The heavy metal content in these rocks is relatively homogeneous. The areas located much farther from the former mine, especially in the western side, have a sedimentary substrate consisting of Cretaceous marine sediments with different heavy metal contents, compared to the volcanic rocks. In the latter areas, the Ni and Cr content become higher, while the concentration of the other metals decreases.

In Rosia Montana area, there are a few sources of environmental contamination related to the former mining activities in the area, such as Cetate and Carnic open pits, the old mine galleries, two tailings management facilities (Saliste and Gura Rosiei), and a few mine waste dumps (5). As in mining areas from other parts of the world (14), in Rosia Montana, the acid waters discharged from the mine tailings and the old mine galleries into the water streams (Rosia and Corna Creek, Abrud River) (15) are contaminating the water and the sediments (16, 17), and represent a pathway by which the metal contamination is reaching the residential areas. Metal pattern distribution around the mining areas is strongly influenced by their water solubility and mobility (2). Another pathway by which the metal contamination is reaching the residential areas, is mediated by human activity and the wind. Both human activity and the wind are important contributors to the transport of the metals on suspended particles originating in soil and dust, from open mining pits and/or mine tailings, further away from the mining area (18). Climate conditions also, play a role in the transfer of metals from the deposits zone in the mining areas to the soil in the surroundings, as does the carbonate content of the geologic substrate in the deposits zone, which can influence the acid pH created by the sulfide oxidation processes, thus influencing the mobilization of metals (2, 19). Other elements that might affect the metal contamination extent into the residential areas near the mining sites, are the geochemical particularities and the degree of tailings mineralization (20). Also, chemical processes such as precipitation, co-precipitation and sorption determine the amount of metals discharged via sulfide oxidation processes (21, 22).

Knowing the environmental contaminant sources and sinks, transport and soil/dust transfer mechanism from the outdoor to the indoor environment is essential for the exposure assessment and health hazard evaluation in the population groups living near mining sites with mining-impacted waters, soils or sediments (23).

One of the major limitations of our study was that we used the X-ray fluorescence technique to analyze for the metals in residential soil samples. To address this limitation, in 2015, we collected additional soil and dust samples from the area, to complete our database and increase the statistical power, and to be able to better assess the exposure and look deeper into the soil/dust transfer mechanism of hazardous contaminants from the outside to the inside environment. These data will also help to characterize health risks posed by the exposure in this highly contaminated former mining area. We plan to analyze these soil samples using sequential extractions and X-ray spectroscopy (XANES and EXAFS) to determine the COCs speciation as described by Al-Abed et al. (24) and D’Amore et al. (25), in order to better characterize the chemical conversion of the contaminants of concern, occurring in the environmental media.

In the future, we will incorporate in our study, the collection of drinking water samples and water samples from streams, to better assess the exposure and will fill in the pathway exposure model by integrating the soil/dust transfer from outside to the indoor environment, which is providing a ‘sink’ for potentially continuous exposure in residences in or near (within 3 km) mining sites.

Conclusion

Environmental policies in the European Union (EU) are increasingly focusing on integrating media protection (air, water and land) and emphasizing multi-statute education, research, permitting for new industrial activities and implement environmental rehabilitation at historically contaminated sites. As Romania and the EU face increasing demands on limited resources, it becomes even more critical that each member state manage its responsibilities efficiently, including those related to mining. Due to Romania’s history of widespread mining in the Carpathians, responsibilities that address mining-related environmental concerns should be prioritized, as the issue affects a disproportionate amount of the country’s land and water resources.

Acknowledgments:

This paper has been subjected to the US Environmental Protection Agency’s internal and quality assurance review. The research results presented herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Agency or its policy. One of the authors (Calin Baciu) acknowledges the financial support provided by the Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research, CCCDI – UEFISCDI, project 3-005 Tools for sustainable gold mining in EU (SUSMIN).

References

- 1.Tamas CG. Endogenous breccias structures (breccia pipe–breccia dyke) and the petrometallogeny of Rosia Montana ore deposit (Metaliferi Mountains, Romania). Cluj-Napoca: Book of Science House, 2007:230pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarro MC, Perez-Sirvent C, Martinez-Sanchez MJ, Vidal J, Tovar PJ, et al. Abandoned mine sites as a source of contamination by heavy metals: a case study in a semi-arid zone. J Geochem Explor 2008;96:183–93. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Wang Y, Gou X, Su Y, Wang G. Risk assessment of heavy metals in soils and vegetables around non-ferrous metals mining and smelting sites, Baiyin, China. J Environ Sci 2006;18(6):1124–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhuang P, McBride MB, Xia H, Li N, Li Z. Health risk from heavy metals via consumption of food crops in the vicinity of Dabaoshan mine, South China. Sci Total Environ 2009;407(5):1551–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazar AL, Baciu C, Roba C, Dicu T, Pop C, et al. Impact of the past mining activity in Rosia Montana (Romania) on soil and vegetation. Environ Earth Sci 2014;72:4653–66. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qu C-S, Ma Z-W, Yang J, Liu Y, Bi J, et al. Human exposure pathways of heavy metals in a lead-zinc mining area, Jiangsu Province, China. PLoS One 2012;7(11):e46793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong S, von Schirnding YE, Prapamontol T. Environmental lead exposure: a public health problem of global dimensions. B World Health Organ 2000;78:1068–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarup L, Hellstrom L, Alfven T, Carlsson MD, Grubb A, et al. Low level exposure to cadmium and early kidney damage: the OSCAR study. Occup Environ Med 2000;57(10):668–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baastrup R, Sørensen M, Balstrøm T, Frederiksen K, Larsen CL, et al. Arsenic in drinking-water and risk for cancer in Denmark. Environ Health Persp 2008;116(2):231–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas LDK, Hodgson S, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Jarup L. Early kidney damage in a population exposed to cadmium and other heavy metals. Environ Health Persp 2009;117(2):181–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosia Montana Gold Corporation (RMGC). Environmental Report for Zonal Urban Plan (PUZ), vol. I, 2007. Available at: http://en.rmgc.ro/rosia-montana-project/environment/environmentevaluation-for-puz.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosia Montana Gold Corporation (RMGC). Environmental Impact Assessment Study – Water Baseline Report, 2007. Available at: http://en.rmgc.ro/rosia-montana-project/environment/environmental-impact-assessment.html.

- 13.Rosia Montana Gold Corporation (RMGC). Environmental Impact Assessment Study –Surface Water Quality, 2007. Available at: http://en.rmgc.ro/rosia-montana-project/environment/environmental-impact-assessment.html.

- 14.Carvalho PCS, Neiva AMR, Silva MMVG, Antunes IMHR. Metal and metalloid leaching from tailings into streamwater and sediments in the old Ag–Pb–Zn Terramonte mine, northern Portugal. Environ Earth Sci 2014;71:2029–41. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stefanescu L, Robu BM, Ozunu A. Integrated approach of environmental impact and risk assessment of Rosia Montana mining area, Romania. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2013;20(11): 7719–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Florea RM, Stoica AI, Baiulescu GE, Capota P. Water pollution in gold mining industry: a case study in Rosia Montana district, Romania. Environ Geol 2005;48:1132–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bird GT, Brewer PA, Macklin MG, Serban M, Balteanu D, et al. Heavy metal contamination in the Aries river catchment, western Romania: implications for development of the Rosia Montana gold deposit. J Geochem Explor 2005;86:26–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adriano DC. Trace elements in terrestrial environments: biogeochemistry, bioavailability and risks of metals, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY, 2001:866pp. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hidalgo MC, Rey J, Benavente J, Martınez J. Hydrogeochemistry of abandoned Pb sulphide mines: the mining district of La Carolina (southern Spain). Environ Earth Sci 2010;61:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson RH, Blowes DW, Robertson WD, Jambor JL. The hydrogeochemistry of the nickel rim mine tailings impoundment, Sudbury, Ontario. J Contam Hydrol 2000;41:49–80. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGregor RG, Blowes DW, Jambor JL, Robertson WD. Mobilization and attenuation of heavy metals within a nickel mine tailings impoundment near Sudbury, Ontario, Canada. Environ Geol 1998;36:305–19. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger AM, Bethke CM, Krumhansl LK. A process model of natural attenuation in drainage from a historic mining district. Appl Geochem 2000;15:655–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fishbein L. Sources, transport and alterations of metal compounds: an overview. I. Arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, chromium, and nickel. Environ Health Persp 1981;40:43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Abed SR, Hageman PL, Jegadeesan G, Madhavan N, Allen D. Comparative evaluation of short-term leach tests for heavy metal release from mineral processing waste. Sci Total Environ 2006;364:14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Amore JJ, Al-Abed SR, Scheckel KG, Ryan JA. Methods for speciation of metals in soils: a review. J Environ Qual 2005;34:170745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]