This cross-sectional study investigates the adequacy of blood pressure control among stroke survivors and antihypertensive treatment trends using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data.

Key Points

Question

Among stroke survivors, what are the national rates of blood pressure control and trends in antihypertensive treatment?

Findings

In this analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional surveys conducted between 2005 and 2016, 37% of an estimated 6.4 million adults with a history of stroke had uncontrolled blood pressure, despite 80% of them taking antihypertensive medication. The most commonly used antihypertensive medications were angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, with diuretics becoming less commonly used over time; no class of antihypertensive medication had statistically significantly higher frequency of blood pressure control.

Meaning

Substantial undertreatment of hypertension was found in individuals with a history of stroke; these data demonstrate a missed opportunity nationally for secondary stroke prevention.

Abstract

Importance

Hypertension is a well-established, modifiable risk factor for stroke. National hypertension management trends among stroke survivors may provide important insight into secondary preventive treatment gaps.

Objective

To investigate the adequacy of blood pressure control among stroke survivors and antihypertensive treatment trends using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Cross-sectional surveys conducted between 2005 and 2016 of nationally representative samples of the civilian US population were analyzed from March 2019 to January 2020. The NHANES is a large, nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted in 2-year cycles in the United States. Evaluations include interviews, medication lists, physical examinations, and laboratory tests on blood samples. Among 221 982 140 adults 20 years or older in the NHANES from 2005 through 2016, a total of 4 971 136 had stroke and hypertension and were included in this analysis, with 217 011 004 excluded from the primary analysis.

Exposures

Hypertension was defined by self-report, antihypertensive medication use, or uncontrolled blood pressure (>140/90 mm Hg) on physical examination. Antihypertensive medication was classified as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, or other.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Weighted frequencies and means were reported using NHANES methods, estimating the proportion of individuals with stroke and hypertension. For all other analyses, 4 971 136 individuals with stroke and hypertension were examined, summarizing number and classes of antihypertensive medications, frequency of uncontrolled hypertension, and associations between antihypertensive classes and blood pressure control. Trends in antihypertensive medication use over time were examined.

Results

Among 4 971 136 individuals with a history of stroke and hypertension, the mean age was 67.1 (95% CI, 66.1-68.1) years, and 2 790 518 (56.1%) were women. In total, 37.1% (33.5%-40.8%) had uncontrolled blood pressure on examination, with 80.4% (82.0%-87.5%) taking antihypertensive medication. The most commonly used antihypertensive medications were angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (59.2%; 95% CI, 54.9%-63.4%) and β-blockers (43.8%; 95% CI, 40.3%-47.3%). Examining trends over time, diuretics have become statistically significantly less commonly used (49.4% in 2005-2006 vs 35.7% in 2015-2016, P = .005), with frequencies of other antihypertensive classes remaining constant.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study that used national survey data, substantial undertreatment of hypertension was found in individuals with a history of stroke, and more than one-third had uncontrolled hypertension. Because hypertension is a major risk factor for stroke, these data demonstrate a missed opportunity nationally for secondary stroke prevention.

Introduction

Stroke remains one of the leading causes of morbidity, disability, and mortality in the United States.1,2 Each year in the United States, more than 750 000 adults experience a stroke, with up to 25% being recurrent or secondary strokes.3 Hypertension is a major risk factor for secondary stroke and is responsible for most of the global cerebrovascular disease burden.4 The risk of recurrent stroke increases progressively with rising blood pressure.5,6,7 Although the targeted blood pressure goal among individuals with prior ischemic stroke has been debated,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 experts agree that consistently elevated blood pressure exceeding 140/90 mm Hg is associated with increased risk of recurrent stroke4 and should be treated both pharmacologically and with behavior modification.8,9

Despite this knowledge, the prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension remains dangerously high.16 Although substantial efforts have been made to investigate hypertensive management trends and treatment gaps among the general population,17,18,19,20,21,22 comparable information regarding blood pressure control among stroke survivors is lacking. Hypertension management trends among stroke survivors may provide important insight into secondary preventive treatment gaps, with direction for future improved interventions.

Although the benefit of hypertension treatment in stroke survivors is clear, further information regarding treatment adequacy is required. To this end, we aimed to summarize the proportion of individuals in the United States with a history of stroke who also have hypertension, assess the extent of blood pressure control among these individuals, and examine the different antihypertensive regimens used by them, as well as testing associations between antihypertensive classes and blood pressure control.

Methods

Study Design

Using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, cross-sectional surveys conducted between 2005 and 2016 of the civilian US population were analyzed from March 2019 to January 2020. The NHANES is a large, nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted in 2-year cycles in the United States, focusing on health conditions and behaviors, physical examination findings, and laboratory results. The sampling method seeks to create nationally representative estimates for the nonmilitary, noninstitutionalized US population using a complex, multistage probability design that samples individuals in strata defined by geographic location and race/ethnicity. Evaluations include interviews, medication lists, physical examinations, and laboratory tests on blood samples. Among 221 982 140 adults 20 years or older in the NHANES from 2005 through 2016, a total of 4 971 136 had stroke and hypertension and were included in this analysis, with 217 011 004 excluded from the primary analysis.

The design and methods of the NHANES have been described elsewhere.23 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants by the NHANES, and our study was reviewed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics. For this analysis, all data were obtained from six 2-year NHANES survey cycles from 2005 through 2016 in individuals 20 years and older. The respondents’ actual or imputed date of birth was used to calculate age. Sex was obtained from standardized interviews. Race/ethnicity was self-reported and classified as Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or other, including multiracial. Educational level was assessed by asking the highest level of school completed or the highest degree received and classified as less than high school, high school graduate, or college or above. Socioeconomic status was defined by the income to poverty ratio, which was calculated by dividing household income by the US federal poverty threshold specific to family size and year and was classified as less than 1.00, 1.00 to 2.99, 3.00 to 4.99, and 5.00 or higher. Smoking status was obtained with a standardized questionnaire and classified as current smoking vs other. Drug use was similarly assessed using standardized questionnaires accounting for the use of various substances, including cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamines. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, both obtained during the standardized examination, and dichotomized at a cutoff of 30.

Blood pressure was assessed using an average of 3 consecutive standardized blood pressure readings during the physical examination. Uncontrolled blood pressure was defined as a mean blood pressure exceeding 140/90 mm Hg. History of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, cancer or malignant neoplasm, chronic kidney disease, myocardial infarction, hypertension, and stroke was obtained by participant report that a physician or other health professional had previously diagnosed that particular condition. Coronary artery disease was defined by self-reported history of coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction. Diabetes was defined by self-reported history or use of antidiabetic agents. Hyperlipidemia was defined by self-reported history or use of cholesterol-modifying agents. Hypertension was defined by self-reported history, self-reported antihypertensive medication use, or uncontrolled blood pressure (>140/90 mm Hg) on physical examination. Antihypertensive medication was classified as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ACE/ARB), diuretic, β-blocker, calcium channel blocker (CCB), or other. Weighted frequencies and means were reported using NHANES methods, estimating the proportion of individuals with stroke and hypertension. For all other analyses, 4 971 136 individuals with stroke and hypertension were examined, summarizing number and classes of antihypertensive medications, frequency of uncontrolled hypertension, and associations between antihypertensive classes and blood pressure control. Trends in antihypertensive medication use over time were examined.

Use of antihypertensive, diabetes, and cholesterol-modifying medications was assessed by self-report. All reported drug names were recorded as standard generic drug, with an associated unique generic drug code from the Multum Lexicon drug database used for drug classification.24 The Multum Lexicon uses a 3-level category system for each generic drug. The first level for all antihypertensive medications was cardiovascular agent. Antihypertensive categories were derived from the second level and grouped into the following classes: ACE/ARB, diuretic, β-blocker, and CCB. The second-level combination agents formed the combination antihypertensive group used for analysis, whereas the remaining second-level cardiovascular agents with antihypertensive properties corresponded to the final other antihypertensive group. Combination agents, which included the 4 primary grouped classes for analysis (ACE/ARB, diuretic, β-blocker, and CCB), were identified using the third-level categories and added to the respective group. Further subcategorization of thiazide diuretic was also derived from the third level, with all other second-level diuretic categories grouped as other diuretic. Polytherapy was defined as the use of more than one antihypertensive medication with a unique drug code. All antidiabetic agents were identified by reported use of medications defined by first-level metabolic and second-level antidiabetic agent from the Multum Lexicon. All cholesterol-modifying agents were identified by reported use of medications defined by first-level metabolic, second-level antihyperlipidemic agent from the Multum Lexicon.

Statistical Analysis

Because of the complex, multistage sampling in the NHANES, specific procedures must be used that incorporate the stratum, cluster, and weighting of data from each individual to accurately estimate associations and variances. We followed the specifications and recommendations for analysis and weighting outlined on the NHANES website.25 Specifically, among the available weights for each survey component, the weight of each individual was chosen based on the selection group of the most restrictive variable. Because 6 survey cycles of the continuous NHANES survey were combined, each weight was divided by 6. We first calculated the weighted frequency of individuals with a history of stroke from 2005 to 2016 and the proportion of these with hypertension, awareness of having hypertension, having an antihypertensive medication prescription, and reporting antihypertensive medication use.

For the remainder of the analysis, we focused on individuals with a history of stroke and hypertension. Distributions of variables were calculated using the procedure SURVEYMEANS for continuous variables and SURVEYFREQ for categorical variables (SAS, version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc), and results were summarized with means (95% CIs) for continuous variables or proportions (95% CIs) for categorical variables. The frequency of antihypertensive medication use by medical class was then calculated as well as the frequency of uncontrolled blood pressure. Next, the sample was stratified into those with and without uncontrolled blood pressure as well as summarized frequencies of antihypertensive medication use by class. Finally, frequencies of blood pressure control and antihypertensive medication use were examined by class in 2-year NHANES cycles from 2005-2006 through 2015-2016. Trends over time were analyzed via linear regression models, with statistical significance set at 2-sided P < .05.

Results

Among an estimated 6.4 million adults with a history of stroke from 2005 to 2016, 78.2% (5.0 million) had hypertension, whereas only 74.3% (4.7 million) reported being aware of having hypertension. In total, 69.6% (4.4 million) had been prescribed antihypertensive therapy; however, only 64.4% (4.1 million) reported taking antihypertensive medication.

The population-weighted descriptive statistics of adults with a history of stroke and hypertension (n = 4 971 136) are listed in Table 1. The mean age was 67.1 (95% CI, 66.1-68.1) years, and 2 790 518 (56.1%) were women. The mean blood pressure was 134/68 (95% CI, 133/67 to 136/69) mm Hg, and the mean number of antihypertensive medications was 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7-1.9). Although most individuals identified their race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic white, other characteristics, such as sex, educational level, and income to poverty ratio, were evenly distributed among the population sample. In total, 4 721 409 of 4 971 136 individuals with a history of stroke and hypertension (95.0%) were aware of their hypertension diagnosis; more than 10% of these individuals had not been previously prescribed an antihypertensive medication, despite awareness of their disease. Additional medical comorbidities and risk factor frequencies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Nationally Representative Population-Weighted Descriptive Statistics of Individuals With a History of Stroke and Hypertensiona.

| Categorical variable | Weighted frequency (N = 4 971 136) | % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 2 790 518 | 56.1 (52.4-59.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 354 239 | 7.1 (5.4-8.8) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 3 458 906 | 69.6 (65.3-73.8) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 804 545 | 16.2 (13.0-19.4) |

| Other | 353 446 | 7.1 (4.9-9.4) |

| Highest educational level | ||

| Less than high school | 1 459 858 | 29.4 (26.0-32.8) |

| High school graduate | 1 470 372 | 29.6 (25.8-33.3) |

| College or above | 2 040 906 | 41.1 (36.9-45.3) |

| Income to poverty ratiob | ||

| <1.00 | 2 223 644 | 44.7 (41.5-48.0) |

| 1.00-2.99 | 1 441 393 | 29.0 (25.2-32.8) |

| 3.00-4.99 | 809 876 | 16.3 (13.0-19.6) |

| ≥5.00 | 496 222 | 10.0 (7.1-12.8) |

| Medical comorbidities | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 1 535 549 | 30.9 (26.8-35.0) |

| Congestive heart failure | 928 933 | 18.7 (15.3-22.0) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 614 080 | 72.7 (69.0-76.4) |

| Diabetes | 1 657 161 | 33.3 (29.6-37.0) |

| Cancer or malignant neoplasm | 1 098 886 | 22.1 (18.6-25.6) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 622 999 | 12.5 (10.7-14.3) |

| Current smoking | 1 152 760 | 23.2 (19.7-26.7) |

| Drug use | 348 371 | 7.0 (4.8-9.2) |

| BMI >30 | 2 068 298 | 41.6 (37.6-45.6) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Continuous variables include the following: mean age, 67.1 (95% CI, 66.1-68.1) years; mean systolic blood pressure, 134.4 (132.5-136.2) mm Hg; mean diastolic blood pressure, 68.0 (66.7-69.3) mm Hg; and mean number of antihypertensive medications, 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7-1.9).

The survey weighting methods sometimes resulted in decimal numbers as estimates. When rounded and summed, the numbers may not add exactly to the heading totals.

The distribution of antihypertensive medication use among individuals with a history of stroke and hypertension is listed in Table 2. In total, 37.1% (95% CI, 33.5%-40.8%) had uncontrolled hypertension on examination, and 15.3% (95% CI, 12.5%-18.0%) were not taking any antihypertensive medication. Of the 84.7% (95% CI, 82.0%-87.5%) of individuals taking antihypertensive medication, the most commonly used antihypertensive medications were ACEs/ARBs (59.2%; 95% CI, 54.9%-63.4%) and β-blockers (43.8%; 95% CI, 40.3%-47.3%), followed by diuretics (41.6%; 95% CI, 37.3%-45.9%) and CCB (31.5%; 95% CI, 28.2%-34.8%). In total, 56.7% (95% CI, 52.8%-60.6%) of individuals were taking more than 1 antihypertensive medication, whereas 28.0% (95% CI, 24.6%-31.5%) were taking only 1.

Table 2. Frequency of Antihypertensive Medication Use Among Individuals With a History of Stroke and Hypertension.

| Variable | Weighted frequency (N = 4 971 136) | % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled blood pressure | 1 846 470 | 37.1 (33.5-40.8) |

| Taking antihypertensive medication | 4 211 423 | 84.7 (82.0-87.5) |

| ACE/ARB | 2 940 545 | 59.2 (54.9-63.4) |

| Diuretic | 2 069 015 | 41.6 (37.3-45.9) |

| Thiazide | 1 218 446 | 24.5 (21.0-28.0) |

| Other diuretic | 954 984 | 19.2 (16.3-22.1) |

| β-Blocker | 2 175 112 | 43.8 (40.3-47.3) |

| CCB | 1 566 907 | 31.5 (28.2-34.8) |

| Other | 239 932 | 4.8 (3.3-6.3) |

| Combination medication | 705 565 | 14.2 (11.1-17.3) |

| Monotherapy | 1 392 825 | 28.0 (24.6-31.5) |

| Polytherapy | 2 818 598 | 56.7 (52.8-60.6) |

Abbreviations: ACE/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

Frequencies of antihypertensive class use were then analyzed after separation of individuals into cohorts of controlled or uncontrolled blood pressure (Table 3). Among individuals with uncontrolled blood pressure, 80.4% (82.0%-87.5%) were taking antihypertensive medication. In comparison, individuals with controlled blood pressure were more likely to be taking any antihypertensive medication across class type, except for CCBs (29.9% vs 34.3%) and other antihypertensive classes (3.9% vs 6.3%), which were more common among individuals with uncontrolled blood pressure. Table 4 summarizes the frequency of blood pressure control according to specific antihypertensive class use. Among individuals taking antihypertensive medication, 64.7% had controlled blood pressure. No class of antihypertensive medication had statistically significantly higher frequency of blood pressure control; however, those taking diuretics (65.9%), specifically thiazides (70.5%), had the highest frequency of blood pressure control, whereas individuals taking CCBs (59.6%) or other antihypertensive classes (51.2%) had the lowest frequency of blood pressure control. We found no statistically significant association between polytherapy and blood pressure control.

Table 3. Frequency of Antihypertensive Medication Use Among 4 971 135 Individuals With Controlled or Uncontrolled Blood Pressure.

| Variable | Weighted frequency, % | |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled blood pressure (n = 3 124 665) | Uncontrolled blood pressure (n = 1 846 470) | |

| Taking antihypertensive medication | 2 726 058 (87.2) | 1 485 365 (80.4) |

| ACE/ARB | 1 906 327 (61.0) | 1 034 218 (56.0) |

| Diuretic | 1 363 194 (43.6) | 705 821 (38.2) |

| Thiazide | 858 490 (27.5) | 359 956 (19.5) |

| Other diuretic | 570 818 (18.3) | 384 165 (20.8) |

| β-Blocker | 1 388 270 (44.4) | 786 842 (42.6) |

| CCB | 934 152 (29.9) | 632 756 (34.3) |

| Other | 122 818 (3.9) | 117 115 (6.3) |

| Combination medication | 207 671 (6.6) | 80 313 (4.3) |

| Monotherapy | 937 111 (30.0) | 455 715 (24.7) |

| Polytherapy | 1 788 947 (57.3) | 1 029 651 (55.8) |

Abbreviations: ACE/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

Table 4. Frequency of Controlled Blood Pressure Among Individuals Taking Specific Antihypertensive Medications.

| Variable | Total frequency | Controlled blood pressure frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taking antihypertensive medication | 4 211 423 | 2 726 058 | 64.7 |

| ACE/ARB | 2 940 545 | 1 906 327 | 64.8 |

| Diuretic | 2 069 015 | 1 363 194 | 65.9 |

| Thiazide | 1 218 446 | 858 490 | 70.5 |

| Other diuretic | 954 984 | 570 818 | 59.8 |

| β-Blocker | 2 175 112 | 1 388 270 | 63.8 |

| CCB | 1 566 907 | 934 152 | 59.6 |

| Other | 239 933 | 122 818 | 51.2 |

| Combination medication | 705 565 | 484 883 | 68.7 |

| Monotherapy | 1 392 825 | 937 111 | 67.3 |

| Polytherapy | 2 818 598 | 1 788 947 | 63.5 |

Abbreviations: ACE/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker.

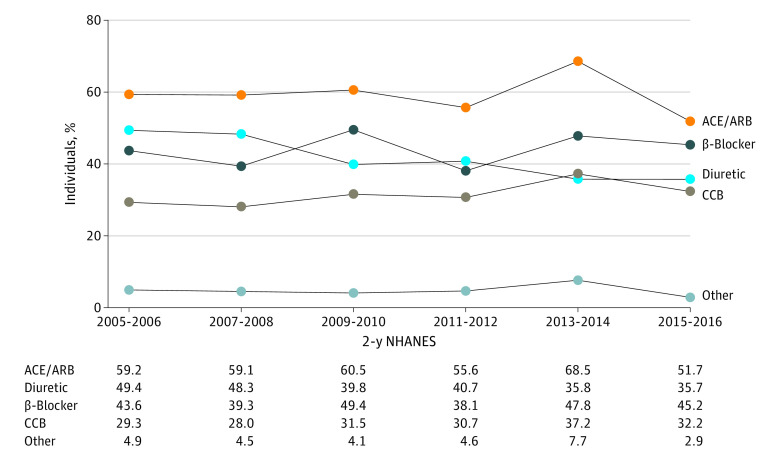

Among individuals with stroke and hypertension, the frequency of both antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control has remained constant from 2005 through 2016. The use of diuretics over time statistically significantly declined (P = .005), from 49.4% in 2005-2006 to 35.7% in 2015-2016, with frequencies of other antihypertensive classes remaining constant (Figure).

Figure. Trends in Antihypertensive Medication Class Use Among Individuals With a History of Stroke and Hypertension (2005-2016).

ACE/ARB indicates angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; and NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Discussion

Using NHANES data, we found that an estimated 5.0 million US adults with a history of stroke from 2005 to 2016 also had hypertension. Of these stroke survivors, 1 in 3 have uncontrolled blood pressure (>140/90 mm Hg), and 1 in 5 did not report taking any medication for their hypertension. Even among those who reported taking their prescribed antihypertensive medication, approximately one-third continued to have uncontrolled blood pressure, despite medication use. Of the antihypertensive medications used by this population, ACEs/ARBs were the most common, followed by β-blockers, diuretics, and CCBs. However, no statistically significant differences or trends were found in the distribution of antihypertensive medication use among stroke survivors with controlled or uncontrolled hypertension.

The prevalence and blood pressure trends among adults with hypertension derived from the NHANES database have been previously described.26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 Approximately one-third of the general population have hypertension.27 This prevalence appears to have remained unchanged since 2000; however, rates of blood pressure treatment and control have increased over time.26,27 Although the association between stroke and hypertension has been previously described in the NHANES,36,37,38,39,40 information about hypertension and blood pressure control specifically among stroke survivors is lacking.

The 78.2% prevalence of hypertension among individuals with prior stroke described in the present study is consistent with previous analyses using data from the NHANES cohorts dating back to the 1980s.38,41,42 These studies also report similar rates of antihypertensive medication use; however, they describe higher rates of uncontrolled blood pressure. Although we report that 37.1% of individuals with prior stroke had uncontrolled blood pressure on examination, previous data, specifically from 1999 to 2004, describe rates of uncontrolled blood pressure exceeding 50%.41,42 These rates align with those reported in individuals with hypertension among the general population during the same period.26,27,43 As rates of blood pressure control have increased in the general population, it may be that so too have rates of blood pressure control increased among patients with prior stroke.

These increased rates of control of hypertension among the general population have been largely attributed to an aggressive campaign to improve patient awareness over the past 20 years.17,22,43 Although there has been a parallel increase in blood pressure treatment and control with rates of awareness among all individuals with hypertension,17,18,19,21,22,26,35,43,44 the same is not apparent among those with a history of stroke. This analysis found that about 95% of individuals with a history of stroke and hypertension were aware of their hypertension diagnosis, yet more than 10% of these individuals had not been previously prescribed an antihypertensive medication, despite awareness of their disease. A recent study45 reported substantial disparities in the prescription of antihypertensive medication after hospitalization for stroke. Clinicians were less likely to discharge patients with stroke and hypertension on an antihypertensive medication regimen unless they had been previously diagnosed as having hypertension, and they were influenced on the decision by factors outside of blood pressure control, including sex, stroke severity, and presence of dementia. Whether this hesitancy to prescribe new antihypertensive medication after hospitalization for stroke is because of clinician bias or a continued debate on the ideal poststroke blood pressure parameters is difficult to determine.6,7,10,11,46,47,48,49,50,51 Nonetheless, this discrepancy in hypertension diagnosis and prescription of antihypertensive medication is worth further exploration.

The most common antihypertensive medications among individuals with prior stroke were ACEs/ARBs, followed by β-blockers, continuing a trend seen since 1999 in the general population.52 In the past 20 years, studies20,52,53,54,55 have shown an overwhelming increase in ACE/ARB use among individuals with hypertension, surpassing prescription of the previously preferred class of diuretics. Use of β-blockers has also increased; among individuals with a history of stroke, we found that their use has exceeded that of diuretics during the past decade as the second most frequently used antihypertensive medication. We report increased rates of blood pressure control compared with previous studies53,55; however, we found no statistically significant association between the class of antihypertensive medication used and blood pressure control.

Among the antihypertensive medication trends identified in individuals with hypertension is increased use of polytherapy to achieve blood pressure control. Previous literature has suggested that at least 2 medications may be needed to adequately control hypertension in most adults,56 and a 2012 study53 using the NHANES database primarily attributed the higher rates of blood pressure control seen between 2001 and 2010 to increased rates of polytherapy regimens. That study53 reported that individuals with hypertension receiving polytherapy regimens were most likely to meet their blood pressure goals. Although the study53 found an increase in polytherapy from 27% to 32% among individuals with hypertension, other subset analyses have found that nearly 50% of individuals with a history of stroke and hypertension take 2 or more antihypertensive medications.42,55,57 We found that 56.7% of individuals with a history of stroke and hypertension adhere to polytherapy antihypertensive regimens. Although we did not find a statistically significant association between polytherapy and blood pressure control, the continued increase in polytherapy may partially account for the higher rates of blood pressure control observed herein.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the present study include that the NHANES database comprises a large, nationally representative sample of the US population over many years. Blood pressure was measured using a standardized approach, minimizing bias by taking the average of 3 consecutive readings obtained under the same conditions. Medical histories were collected by trained examiners using established protocols. Prescription medications were also verified with drug containers, helping to eliminate known biases associated with self-report.

Our study also has limitations. The NHANES relies on self-reported history of stroke. The NHANES has not validated its self-reporting of stroke; however, self-reported stroke is sensitive, specific, and reliable.58,59 Although blood pressure measurements were repeated and standardized, we only had data on blood pressure at a single time point, confounding reliable identification of ambulatory controlled or uncontrolled hypertension. The effectiveness and necessity of antihypertensive medication may also differ by stroke etiology, and we were unable to distinguish subtypes of stroke given limitations of the NHANES survey. Many antihypertensive medications, specifically β-blockers, are also frequently prescribed for indications other than hypertension, thereby introducing another confounding factor to medication trends.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to analyze and report national antihypertensive medication trends exclusively among individuals with a history of stroke in the United States and includes the most recent data on hypertension prevalence and blood pressure control among these stroke survivors. Although this study reveals a gap in secondary prevention of stroke, future studies are needed to determine preferential antihypertensive medication in patients after stroke. Studies focused on the efficacy of the class and number of antihypertensive medications in this patient population may be particularly beneficial. Additional identification of socioeconomic obstacles to treatment and nonpharmacological interventions among individuals with a history of stroke may also be indicated.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. ; Writing Group Members; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics–2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics Health, United States, 2014: With Special Feature on Adults Aged 55-64. National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Report 2015-1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease . Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Donnell MJ, Chin SL, Rangarajan S, et al. ; INTERSTROKE Investigators . Global and regional effects of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with acute stroke in 32 countries (INTERSTROKE): a case-control study. Lancet. 2016;388(10046):761-775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30506-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R; Prospective Studies Collaboration . Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9349):1903-1913. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11911-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawes CMM, Bennett DA, Feigin VL, Rodgers A. Blood pressure and stroke: an overview of published reviews. Stroke. 2004;35(4):1024-1033. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000126208.14181.DD [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katsanos AH, Filippatou A, Manios E, et al. . Blood pressure reduction and secondary stroke prevention: a systematic review and metaregression analysis of randomized clinical trials. Hypertension. 2017;69(1):171-179. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. . 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):e13-e115. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. . 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okin PM, Kjeldsen SE, Devereux RB. Systolic blood pressure control and mortality after stroke in hypertensive patients. Stroke. 2015;46(8):2113-2118. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin MP, Ovbiagele B, Markovic D, Towfighi A. Systolic blood pressure and mortality after stroke: too low, no go? Stroke. 2015;46(5):1307-1313. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gueyffier F, Boissel JP, Boutitie F, et al. ; INDANA (Individual Data Analysis of Antihypertensive Intervention Trials) Project Collaborators . Effect of antihypertensive treatment in patients having already suffered from stroke: gathering the evidence. Stroke. 1997;28(12):2557-2562. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.28.12.2557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arima H, Chalmers J, Woodward M, et al. ; PROGRESS Collaborative Group . Lower target blood pressures are safe and effective for the prevention of recurrent stroke: the PROGRESS trial. J Hypertens. 2006;24(6):1201-1208. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226212.34055.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalmers J, MacMahon S. Perindopril pROtection aGainst REcurrent Stroke Study (PROGRESS): interpretation and implementation. J Hypertens Suppl. 2003;21(5):S9-S14. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200306005-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Gijn J. The PROGRESS trial: preventing strokes by lowering blood pressure in patients with cerebral ischemia: emerging therapies: critique of an important advance. Stroke. 2002;33(1):319-320. doi: 10.1161/str.33.1.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fryar CD, Ostchega Y, Hales CM, Zhang G, Kruszon-Moran D. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(289):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo F, He D, Zhang W, Walton RG. Trends in prevalence, awareness, management, and control of hypertension among United States adults, 1999 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(7):599-606. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988-2000. JAMA. 2003;290(2):199-206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Simon PA, Kuo T, Ogden CL. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control among adults aged ≥18 years: Los Angeles County, 1999-2006 and 2007-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(32):846-849. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6632a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarganas G, Knopf H, Grams D, Neuhauser HK. Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among adults with hypertension in Germany. Am J Hypertens. 2016;29(1):104-113. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpv067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon SSS, Carroll MD, Fryar CD. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(220):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoon SS, Gu Q, Nwankwo T, Wright JD, Hong Y, Burt V. Trends in blood pressure among adults with hypertension: United States, 2003 to 2012. Hypertension. 2015;65(1):54-61. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Health Statistics The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Analytic and Reporting Guidelines. Accessed January 31, 2020. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analyticguidelines.aspx

- 24.Cerner Multum. Drug database. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://www.cerner.com/solutions/drug-database

- 25.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Module 3: weighting. Accessed December 1, 2019. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/tutorials/module3.aspx

- 26.Ong KL, Cheung BMY, Man YB, Lau CP, Lam KSL. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999-2004. Hypertension. 2007;49(1):69-75. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252676.46043.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension: United States, 1999-2002 and 2005-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):103-108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, et al. . Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1991. Hypertension. 1995;25(3):305-313. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.25.3.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogden LG, He J, Lydick E, Whelton PK. Long-term absolute benefit of lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients according to the JNC VI risk stratification. Hypertension. 2000;35(2):539-543. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.35.2.539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Larson MG, O’Donnell CJ, Roccella EJ, Levy D. Differential control of systolic and diastolic blood pressure: factors associated with lack of blood pressure control in the community. Hypertension. 2000;36(4):594-599. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.36.4.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franklin SS, Jacobs MJ, Wong ND, L’Italien GJ, Lapuerta P. Predominance of isolated systolic hypertension among middle-aged and elderly US hypertensives: analysis based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Hypertension. 2001;37(3):869-874. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.37.3.869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, et al. . Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010;375(9718):895-905. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60308-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bautista LE. Predictors of persistence with antihypertensive therapy: results from the NHANES. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(2):183-188. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muntner P, Shimbo D, Tonelli M, Reynolds K, Arnett DK, Oparil S. The relationship between visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure and all-cause mortality in the general population: findings from NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Hypertension. 2011;57(2):160-166. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burt VL, Cutler JA, Higgins M, et al. . Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the adult US population. Data from the health examination surveys, 1960 to 1991. Hypertension. 1995;26(1):60-69. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.26.1.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J, Gall SL, Nelson MR, Sharman JE, Thrift AG. Lower systolic blood pressure is associated with poorer survival in long-term survivors of stroke. J Hypertens. 2014;32(4):904-911. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin MP, Ovbiagele B, Markovic D, Towfighi A. “Life’s Simple 7” and long-term mortality after stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(11):4. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Towfighi A, Markovic D, Ovbiagele B. Impact of a healthy lifestyle on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality after stroke in the USA. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(2):146-151. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown DW, Giles WH, Greenlund KJ. Blood pressure parameters and risk of fatal stroke, NHANES II Mortality Study. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20(3):338-341. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowman TS, Gaziano JM, Kase CS, Sesso HD, Kurth T. Blood pressure measures and risk of total, ischemic, and hemorrhagic stroke in men. Neurology. 2006;67(5):820-823. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000233981.26176.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kesarwani M, Perez A, Lopez VA, Wong ND, Franklin SS. Cardiovascular comorbidities and blood pressure control in stroke survivors. J Hypertens. 2009;27(5):1056-1063. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832935ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Razmara A, Ovbiagele B, Markovic D, Towfighi A. Patterns and predictors of blood pressure treatment, control, and outcomes among stroke survivors in the United States. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(4):857-865. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988-2008. JAMA. 2010;303(20):2043-2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ostchega Y, Yoon SS, Hughes J, Louis T. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control: continued disparities in adults: United States, 2005-2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2008;(3):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalli LL, Kim J, Thrift AG, et al. . Disparities in antihypertensive prescribing after stroke: linked data from the Australian Stroke Clinical Registry. Stroke. 2019;50(12):3592-3599. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Webb AJ, Fischer U, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM. Effects of antihypertensive-drug class on interindividual variation in blood pressure and risk of stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9718):906-915. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60235-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ovbiagele B, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. ; PROFESS Investigators . Level of systolic blood pressure within the normal range and risk of recurrent stroke. JAMA. 2011;306(19):2137-2144. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ovbiagele B. Low-normal systolic blood pressure and secondary stroke risk. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22(5):633-638. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al. ; ACCORD Study Group . Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1575-1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper-DeHoff RM, Gong Y, Handberg EM, et al. . Tight blood pressure control and cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease. JAMA. 2010;304(1):61-68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rashid P, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath P. Blood pressure reduction and secondary prevention of stroke and other vascular events: a systematic review. Stroke. 2003;34(11):2741-2748. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000092488.40085.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Dillon C, Burt V. Antihypertensive medication use among US adults with hypertension. Circulation. 2006;113(2):213-221. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.542290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gu Q, Burt VL, Dillon CF, Yoon S. Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among United States adults with hypertension: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001 to 2010. Circulation. 2012;126(17):2105-2114. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dorans KS, Mills KT, Liu Y, He J. Trends in prevalence and control of hypertension according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(11):7. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gu Q, Burt VL, Paulose-Ram R, Dillon CF. Gender differences in hypertension treatment, drug utilization patterns, and blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2004. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(7):789-798. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cushman WC, Ford CE, Cutler JA, et al. ; ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group . Success and predictors of blood pressure control in diverse North American settings: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2002;4(6):393-404. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.02045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gu A, Yue Y, Desai RP, Argulian E. Racial and ethnic differences in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003 to 2012. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(1):10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Mahony PG, Dobson R, Rodgers H, James OF, Thomson RG. Validation of a population screening questionnaire to assess prevalence of stroke. Stroke. 1995;26(8):1334-1337. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.26.8.1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Engstad T, Bonaa KH, Viitanen M. Validity of self-reported stroke: the Tromsø Study. Stroke. 2000;31(7):1602-1607. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.7.1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]