Abstract

The dysregulation of Wnt signaling is a frequent occurrence in many different cancers. Oncogenic mutations of CTNNB1/β-catenin, the key nuclear effector of canonical Wnt signaling, lead to the accumulation and stabilization of β-catenin protein with diverse effects in cancer cells. Although the transcriptional response to Wnt/β-catenin signaling activation has been widely studied, an integrated understanding of the effects of oncogenic β-catenin on molecular networks is lacking. We used affinity-purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS), label-free liquid chromatography– tandem mass spectrometry, and RNA-Seq to compare protein–protein interactions, protein expression, and gene expression in colorectal cancer cells expressing mutant (oncogenic) or wild-type β-catenin. We generate an integrated molecular network and use it to identify novel protein modules that are associated with mutant or wild-type β-catenin. We identify a DNA methyltransferase I associated subnetwork that is enriched in cells with mutant β-catenin and a subnetwork enriched in wild-type cells associated with the CDKN2A tumor suppressor, linking these processes to the transformation of colorectal cancer cells through oncogenic β-catenin signaling. In summary, multiomics analysis of a defined colorectal cancer cell model provides a significantly more comprehensive identification of functional molecular networks associated with oncogenic β-catenin signaling.

Keywords: Wnt signaling, β-catenin, oncogenic mutations, protein–protein interaction network, multiomics integration, DNA methyltransferase I

INTRODUCTION

Altered activity of Wnt and β-catenin signaling is a key driver of tumorigenesis in many cancers. Stabilizing mutations of β-catenin are an important class of mutations that alter canonical Wnt signaling and function by blocking the phosphorylation of residues that would normally target the protein for destruction.1 Substitution or deletion mutations at S45 of β-catenin are important clinical mutations in diverse tumors because this residue acts as a critical molecular switch for canonical Wnt signaling.1,2 Elevated β-catenin levels then exert oncogenic effects through the activation of downstream gene-expression programs in concert with TCF transcription factors.3 In addition to its role as a transcriptional effector, β-catenin functions as a component of cell–cell adhesion complexes, although the relative balance between β-catenin’s different cellular functions is complex.4 As expected, given its diverse functions and subcellular localizations, β-catenin exhibits a wide range of different protein interactions with other structural proteins in adhesion complexes, proteins in the destruction complex,5 and nuclear interactions with transcription and chromatin modification factors.6 In addition, transcriptional targets of β-catenin and TCF signaling have been defined in many systems; in cancer cells, these include other transcription factors, regulators of the cell cycle, and components and antagonists of the Wnt signaling pathway (Wnt home page; http://wnt.stanford.edu).

Omics analyses of Wnt activation to date have focused on understanding a single molecular layer of the response to Wnt activation, such as proteomic analyses of selected Wnt pathway components7,8 or the proteomic- or transcriptomic-expression response to Wnt activation.9,10 However, the response to the activation of cell signaling pathways occurs at multiple molecular levels; recent work has shown how the activation of the Wnt pathway leads directly to protein stabilization in addition to the well-studied transcriptional response.11 In addition, although it is convenient to consider proximal events in cell signaling (i.e., components of the pathway itself) separately from the response or output of signaling activation (e.g., transcriptional activation), these are intrinsically linked. Several core protein components of the Wnt signaling pathway (e.g., Axin and Dkk) are themselves transcriptional targets and directly activated through β-catenin and TCF signaling and providing feedback regulation of the Wnt signaling activity12,13

To understand, therefore, how oncogenic β-catenin alters networks at multiple molecular levels and how this promotes tumorigenesis, we conducted a multiomics analysis using colorectal cancer cells with targeted inactivation of either the mutant (stabilizing Δ45 mutation) or the wild-type allele of CTNNB1/β-catenin.14 Affinity-purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) analysis of mutant and wild-type β-catenin cells showed patterns of protein interactions consistent with the nuclear localization of mutant β-catenin and membrane-associated wild-type β-catenin. Integrating AP-MS and expression proteomic profiling, we identified several enriched protein networks that are preferentially expressed in mutant or wild-type cells including elevated DNA-methylation-linked proteins in mutant cells and a nucleolar-enriched tumor-suppressor module in wild-type cells. Through a comparative analysis of enriched Gene Ontology (GO) categories, we show that there is concerted alteration of pathways and processes at the proteomic and transcriptomic levels in the mutant and wild-type cells. We show that interaction-proteomics, expression-proteomics, and transcriptomic data sets contribute complementary information to the integrated network and that multiomics analysis provides a more-comprehensive delineation of β-catenin-associated oncogenesis. In summary, our multiomics analysis provides a comprehensive view of how oncogenic β-catenin alters molecular networks at multiple levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell-Line Culture and Sample Extraction

Colorectal cancer cell lines HCT116-CTNNB1−/Δ45 and HCT116-CTNNB1WT/− were regularly maintained in McCoy-5A media (Life Technologies, 16600–108, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, 10438–026) and 1% streptomycin–penicillin (Life Technologies, 15140–148) at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator (5% CO2 and 100% H2O). Cells were harvested by scraping the cells off plates and then washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline twice for immediate use or storage (−80 °C). Harvested cells were lysed (25 mM Tris–HCl and pH of 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 50% glycerol, and Protease inhibitor cocktail) by homogenization and incubated on ice for 30 min followed by centrifugation at 13 000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant (soluble fraction) was kept for further analysis. Proteins were quantified by Bio-Rad protein assay dye (500–0006, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) by measuring the absorbance at 595 nm. An NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Pierce) was used to prepare nuclear and cytosolic fractions, which were assessed using anti-Dnmt1 and anti-Gapdh Western blots.

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

Equal amounts (20 μg) of proteins from different samples was loaded on precast 4–12% Bis–Tris gel (Life Technologies NP-0335) and subjected to electrophoresis. Gels were either stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Pierce 20278, Rockford, IL) or transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman 10402594, Dassel, Germany). Western blotting was used to detect the protein with super signal ELISA Pico chemiluminescent substrate. Primary antibodies used were anti-β-catenin (Cell Signaling Technology, 9581, Danvers, MA), anti-Dnmt1 (Cell Signaling Technology, 5119), anti-UHRF1 (Novus Biologicals, H00029128-M01, Littleton, CO), anti-HDAC1 (Abcam, ab7028, Cambridge, MA), anti-PCNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-56, Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-α-tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology, 2144). Loading controls were applied at 1:1000, and secondary antibodies of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antimouse (Promega, W4011, Madison, WI) and HRP-conjugated antirabbit (Cell Signaling Technology, 7074) were added at 1:20 000. Chemiluminescence detection using SuperSignal* ELISA Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, PI-37070, Rockford, IL) was applied to all Western blots.

Proteomic Sample Preparation

For analysis of the expression proteome, cell extracts were fractionated using the NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Pierce), with each fraction separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then fractionated in two fractions per sample per lane after Coomassie blue staining prior to tryptic digestion. Each sample combination (e.g., mutant with nuclear and mutant with cytosolic) was replicated twice. Affinity purifications from 107 cells were performed as previously described15 using anti-β-catenin (Cell Signaling Technology, 9581) antibodies. Affinity-purification experiments were replicated using two independent mutant and two independent wild-type cell lines, and each sample was replicated twice. In-gel tryptic digestion was performed, and combined elution fractions were lyophilized in a SpeedVac Concentrator (Thermo Electron Corporation, Milford, MA), resuspended in 100 μL of 0.1% formic acid, and further cleaned by reverse-phase chromatography using C18 column (Harvard, Southborough, MA). The final volume was reduced to 10 μL by vacuum centrifugation and the addition of 0.1% formic acid.

Mass Spectrometry

Online reverse-phase nanoflow capillary liquid chromatography (nano-LC, Dionex Ultimate 3000 series HPLC system) coupled to electrospray ionization (ESI) tandem mass spectrometry (Thermo-Finnegan LTQ Orbitrap Velos) was used to separate and analyze tryptic peptides. Peptides were eluted on nano-LC with 90 min gradients (6 to 73% acetonitrile in 0.5% formic acid with a flow rate of 300 nL/min). Data-dependent acquisition was performed using Xcalibur software (version2.0.6, Thermo Scientific) in positive-ion mode with a resolution of 60 000 at a m/z range of 325.0–1800.0 and using 35% normalized collision energy. Up to the five most-intensive multiple charged ions were sequentially isolated, fragmented, and further analyzed. Raw liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS data) were processed using Mascot version 2.2.0 (Matrix Science, Boston, MA). The sequence database was searched with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.8 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 15 ppm. The raw data were searched against the human International Protein Index database (74 017 protein sequences; version 3.42) with a fixed modification of carbamidomethyl (C), a variable modification of oxidation (M), and one allowed missed cleavage. Peptides were filtered at a significance threshold of p < 0.05 (Mascot). Raw mass-spectrometry chromatograms were processed and analyzed using Xcalibur Qual Browser software (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., version 2.0.7). Scaffold (Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR; version 3.00.04) was used to analyze LC–MS/MS-based peptide and protein identifications. Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95.0% probability, as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm.16 Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 99.0% probability and contained at least 2 identified peptides. Proteins that contained similar peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony. Protein quantitation for the expression proteomics study was performed using ion peak-intensity measurements in the Rosetta Elucidator software (version 3.3.0.1; Rosetta Inpharmatics LLC, Seattle, WA). The PeakTeller algorithm within Rosetta Elucidator was used for the peak detection, extraction, and normalization of peptide and protein abundance. Protein quantitation of AP-MS experiments was performed using Scaffold (Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR, USA; version 3.00.04) to compute normalized spectral counts for each protein. Proteins were excluded from AP-MS results if the frequency across control experiments from HCT116 cells was >0.33.15 Mass spectrometry data are available via the PRIDE repository with data-set identifiers PXD006053 (expression proteome) and PXD006051 (interaction proteome).

RNA-Seq Analysis

The quantity of total RNA in each sample was collected using Qubit (Invitrogen) and libraries prepared using Illumina TruSeq Total RNA v2 kit with Ribo Zero Gold for rRNA removal. The Ribo-Zero kit was used to remove rRNA (rRNA) from 1 μg of total RNA using a hybridization/bead capture procedure that selectively binds rRNA species using biotinylated capture probes. The resulting purified mRNA was used as input for the Illumina TruSeq kit in which libraries are tagged with unique adapter indices. Final libraries were validated using the Agilent high-sensitivity DNA kit (Agilent), quantified via Qubit, and diluted and denatured per Illumina’s standard protocol. High-throughput sequencing was carried out using the Illumina HiScan SQ instrument, 100 cycle paired-end runs, with 1 sample loaded per lane, yielding, on average, >100 million reads per sample. Reads were mapped to human genome hg19 using TopHat2 version 2.1.017 with default settings and reads summarized by gene features using htseqcount. Differential expression analysis was performed and the p values adjusted for false discovery rates (FDR) were computed with DeSeq18 Data are available from GEO (accession no. GSE95670).

Functional and Network Analyses

The combined abundance score, as previously described,19 was computed using all significant (p < 0.05) proteins from the 3 data sets, providing a single, normalized log fold-change value for each protein. (Selected additional protein were included in which the p value was significant at p < 0.1 because it was observed for several proteins that they were differentially abundant across more than one data set, e.g., CUL1). Functional networks were constructed using Pathway Studio (Elsevier), version 9.0. Gene and protein identifiers were imported and networks created by selecting all direct edges between the imported nodes (physical interactions, expression regulation, and protein-modification relations) and network diagrams were created in Cytoscape, version 3.3.0. Edge thickness between two functional groups was calculated by dividing the number of interactions between the groups by the size of the groups (number of genes and proteins), creating a normalized edge weight. GO term enrichment was computed in Pathway Studio (Ariadne Genomics). The significantly differential sets of mutant and wild-type genes from the RNA-Seq analysis were analyzed using Enrichr20 and o-POSSUM-3.21

Experimental Design and Statistical Rationale

AP-MS was performed on two independently derived clones of the HCT116-CTNNB1−/Δ45 and HCT116-CTNNB1WT/− cell lines (i.e., four different cell lines) and then replicated twice. The use of independent clones allowed us to capture the biological variation in the expression of CTNNB1/β-catenin. We observed that AP-MS proteomics experiments produced very similar results between these clones (Supplementary Figure 1). Expression-proteomics experiments were performed on subcellular fractionated mutant and wild-type cell cultures. Each combination of cell type and subcellular fraction (mutant and nuclear, mutant and cytosol, wild-type and nuclear, and wild-type and cytosol) was replicated twice, and we found a high level of correlation within these groups (Supplementary Figure 3). RNA-Seq experiments were performed in triplicate (three mutant and three wild-type), yielding significant differentially regulated transcripts at low FDR. For each data set, the log2 ratio of mutant-to-wild-type abundance was computed, and Student’s t test was used to compute p values with adjustment for FDR.

RESULTS

Experimental Overview

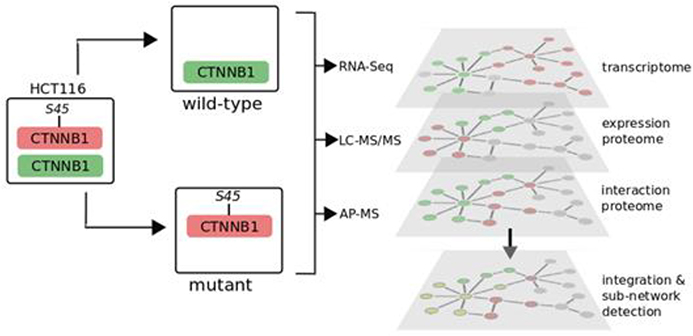

The experimental strategy of this study is to use multiple, complementary omics approaches to identify perturbed molecular networks, as shown in Figure 1. We used a previously described model derived from HCT116 colorectal cancer cells (heterozygous for the stabilizing Δ45 mutation of β-catenin) in which either the mutant or the wild-type allele has been disrupted,14 thus creating two cell-lines expressing either mutant β-catenin (CTNNB1−/Δ45) or wild-type β-catenin (CTNNB1WT/−). To characterize mutant and wild-type β-catenin protein–protein interactions, we used anti-β-catenin affinity-purification mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS AP-MS). We also analyzed nuclear and cytosolic fractions to increase overall coverage using label-free protein profiling (LC–MS/MS) to identify differentially abundant proteins in the mutant and wild-type cells (two replicates of each cell type and fraction combination, a total of eight samples). Finally, we used RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq) to compare the transcriptomes of mutant and wild-type β-catenin cells. Three replicates each of mutant and wild-type cells were analyzed and genes with differential gene-expression profiles identified.

Figure 1.

Integrated multiomics analysis of β-catenin signaling networks. Experimental design and data acquisition of interactome (AP-MS), expression proteome (LC–MS/MS), and transcriptome (RNA-Seq) from colorectal cancer cell lines HCT116-CTNNB1−/Δ45 (mutant) and HCT116-CTNNB1WT/− (wild-type) expressing endogenous mutant or wild-type CTNNB1/β-catenin

AP-MS Analysis Identification of Distinct Mutant and Wild-Type β-catenin Protein Interactions

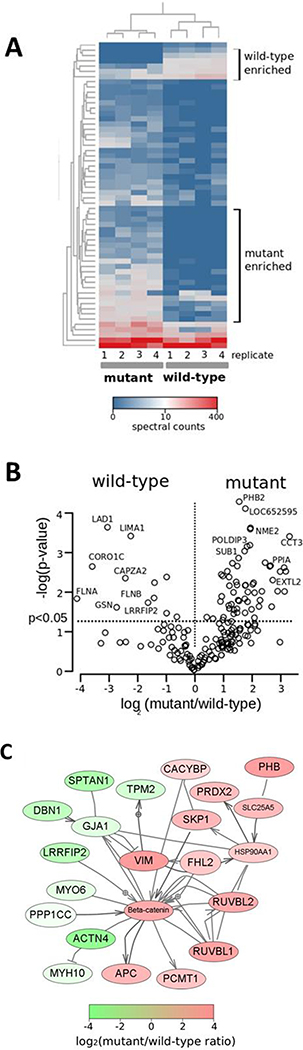

We analyzed the mutant and wild-type β-catenin protein interactions using AP-MS experiments, as shown in Figure 2. AP-MS analyses were performed using two distinct clones each for mutant and wild-type cells (a total of four replicates of mutant and four replicates of wild-type cells), and we observed a high level of correlation of protein abundance in AP-MS analyses between replicates and clones (Supplementary Figure 1). AP-MS experiments yielded 67 proteins differentially associated with mutant or wild-type β-catenin (p < 0.05), and we observed distinct profiles of proteins from the mutant and wild-type AP-MS analyses that are consistent with the differential subcellular localization of mutant and wild-type β-catenin (Supplementary Table 1). Figure 2A shows a heatmap of proteins significant proteins identified in AP-MS experiments, and Figure 2B shows a volcano plot of log2 ratios of mutant and wild-type proteins. We found that mutant protein interactions were highly enriched for nuclear proteins and for proteins functioning in regulation of gene expression, whereas wild-type proteins were significantly enriched for membrane-associated proteins (see Figure 3). To investigate in greater detail, we constructed a protein network of all known physical interactions between the identified set of proteins. The largest connected component of this network is shown in Figure 2C with known mutant-enriched (red) and wild-type-enriched (green) β-catenin interaction partners identified in the analysis. Higher interconnectivity between pairs of proteins identified in the mutant cells was observed than between proteins identified in the wild-type cells (and this is not due to differences in the overall connectivity of mutant- and wild-type-enriched proteins because there is no significant difference between the degree of distributions of the mutant and wild-type proteins: two-sample t test and a p value of >0.3). These findings and the distinct sets of enriched functional categories indicate that β-catenin in the mutant and wild-type cells functions in distinct protein networks, in concordance with distinct subcellular localizations of mutant and wild-type β-catenin.

Figure 2.

AP-MS analysis of mutant and wild-type β-catenin protein interactions. (A) Heatmap of protein spectral counts across four replicate HCT116-CTNNB1−/Δ45 (mutant) and four HCT116-CTNNB1WT/− (wild-type) AP-MS samples. Selected profiles of proteins associated with either mutant AP-MS or wild-type AP-MS samples are shown. (B) Volcano plot indicating log2 ratio of mutant-to-wild-type spectral counts from a single AP-MS study, with significant (p < 0.05) proteins indicated. (C) Network diagram of β-catenin (CTNNB1) interaction partners identified in the study. The largest connected component subnetwork in the Pathway Studio analysis is shown. Proteins are shaded according to their mutant-to-wild-type spectral count ratio (red-shaded proteins are highly enriched in mutant AP-MS samples, and green-shaded proteins are highly enriched in wild-type AP-MS samples).

Figure 3.

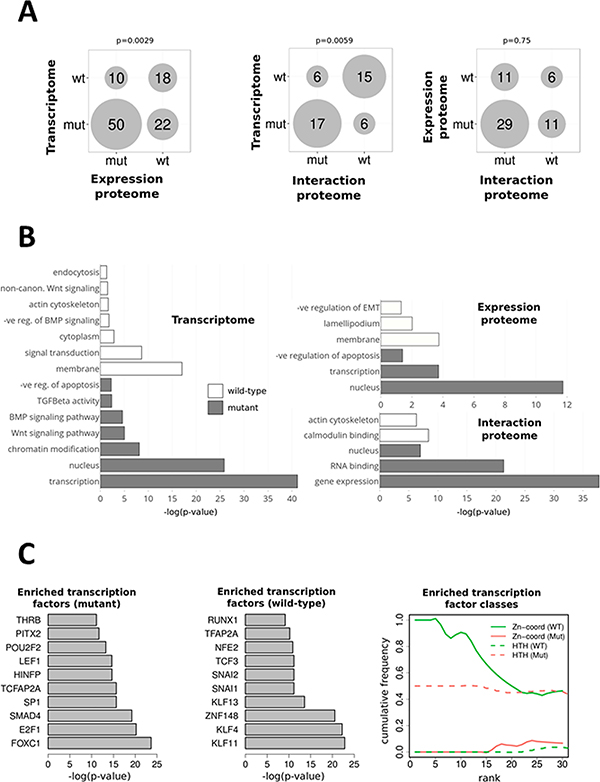

Functional analysis of β-catenin-associated proteomic and transcriptomic profiles (A) Bubble plot indicating the size of the intersections of Gene Ontology (GO) terms between interaction, expression-proteome, and transcriptomic data sets. The numbers indicate shared GO terms for each comparison for GO terms significantly (p < 0.05) enriched in mutant or wild-type samples. The p values are Fisher’s exact test values indicating the significance of the observed overlap of GO terms.(B) Enriched GO terms in mutant and wild-type cells across each data set. The most significantly differential GO terms were identified for each data set by comparing the p values for each term between mutant and wild-type gene sets. (C) Enriched transcription factors in the significantly (p < 0.05) differential mutant or wild-type gene sets from RNA-Seq analysis. Enrichr analysis was used to identify the most-enriched transcription factors in the significantly different (p < 0.05) RNA-Seq data sets. The top 10 enriched transcription factors are shown for mutant and wild-type samples (panel 1 and 2). Ranked transcription factor classes for the mutant and wild-type RNA-Seq significantly different data sets show distinct classes of transcription factors in each cell type.

Comparison of Functional Trends between Mutant and Wild-Type Cells

We next analyzed gene and protein expression in the mutant and wild-type cells using RNA-Seq and LC–MS/MS, respectively. RNA-Seq analysis identified transcripts from 18 239 genes, with 1085 showing significantly differential expression in mutant cells (p < 0.05; log-fold-change >2) and 735 showing significantly differential expression in wild-type cells (FPKM distribution plots; Supplementary Figure 2). To increase protein coverage, we performed protein expression profiling in conjunction with subcellular fractionation of cell lysates. This analysis yielded 640 proteins identified as significantly differentially expressed (p < 0.05) between mutant and wild-type cells in either cytosolic or nuclear fractions. We compared the functional trends in the interaction-proteome, expression-proteome, and transcriptome data sets. For each data set, GO terms significantly (p < 0.05) enriched in mutant or wild-type or both samples were identified and then compared across the data sets. Overlap of significantly differential genes and proteins between the data sets was limited (57 genes and proteins were identified in more than one data set from a combined total of 2465 significantly differentially regulated genes or proteins). However, significant numbers of shared enriched GO terms were identified across all three data sets. The number of shared GO terms is summarized in Figure 3A, and we observed much-greater concordance between mutant-enriched GO terms between data sets and between wild-type-enriched GO terms, indicating a concerted cellular response at proteomic and transcriptomic levels to the β-catenin mutation (Figure 3A). Selected significantly enriched GO terms in either mutant or wild-type cells are shown in Figure 3B, and these reflect the findings for the AP-MS data set, wherein mutant transcriptome and proteome data sets are enriched for nuclear- and gene-expression-associated functions, whereas the wild-type transcriptome and proteome are enriched for membrane- and cytoskeleton-associated functions. In addition, comparison of the differentially regulated RNA-Seq gene sets against two curated repositories, TSGene22 and the Tumor Associated Gene database,23 showed significant enrichment (p = 0.00182; Fisher’s exact) of tumor suppressors and oncogenes (p = 0.02979; Fisher’s exact), indicating that these cancer-relevant functional classes are frequently differentially regulated in the mutant and wild-type β-catenin model.

As expected, the GO analysis showed that canonical Wnt signaling was highly enriched in the mutant cells. We therefore analyzed what direct canonical Wnt signaling targets (taken from the Wnt home page at http://wnt.stanford.edu) bound by TCF transcription factors were differentially expressed between mutant and wild-type cells (Supplementary Table 2) and found that many of the known Wnt targets are differentially regulated in our data, indicating a substantial direct response to β-catenin and TCF. We noted that two classical targets of canonical Wnt signaling, CCND1 (cyclin D1) and MYC (c-myc), were not significantly differential between the mutant and wild-type cells. The same finding was reported in the initial analysis of the same cell lines, and it was concluded that although these genes have been observed as direct transcriptional targets of β-catenin and TCF in many systems,24 they are not physiological targets in these cell lines.14 We next compared our transcriptome data set with two previously published CTNNB1 siRNA analyses in colorectal cancer cells.25,26 This previous study identified a set of 335 genes for which a consistent positive and negative trend was seen across siRNA experiments in 2 colorectal cancer cell-lines. Comparing our transcriptome data set to this set showed a significant overlap and trend correlation (p = 0.0245; Fisher’s exact test), particularly in the correlation between genes whose expression is repressed in response to CTNNB1 siRNA and genes up-regulated in mutant CTNNB1 cells (Supplementary Table 3), indicating that different β-catenin perturbation models (siRNA, knockout) have similar transcriptional outcomes.

To further understand the transcriptional regulatory programs in the mutant or wild-type cells, we analyzed enriched transcription factor binding sites in the mutant or wild-type gene sets (Figure 3C). The β-catenin binding partner Lef1, a TCF transcription factor, is among the most highly represented predictions in the mutant cells. We also noted that the mutant and wild-type gene sets exhibited enrichment of different classes of transcription factor (Figure 3C).The wild-type set is highly enriched in zinc-finger transcription factor binding sites (6 of the top 10 most-enriched TFs are of this type). Multiple Kruppel-like factor (KLF) transcription factors are represented in this set, and this class of transcription factors has been shown to function as tumor suppressors in colorectal cancer.27–29 KLF4 has been shown to interact with β-catenin and inhibit Wnt signaling in the colon.30,31 TCF3 is also identified as an enriched transcription factor in the wild-type cells. Recent analysis showed that TCF3 binds the MYC Wnt-responsive element to inhibit MYC expression by preventing the binding of β-catenin and TCF4 at the same promoter element.32

Integrated Proteomic and Transcriptomic Network

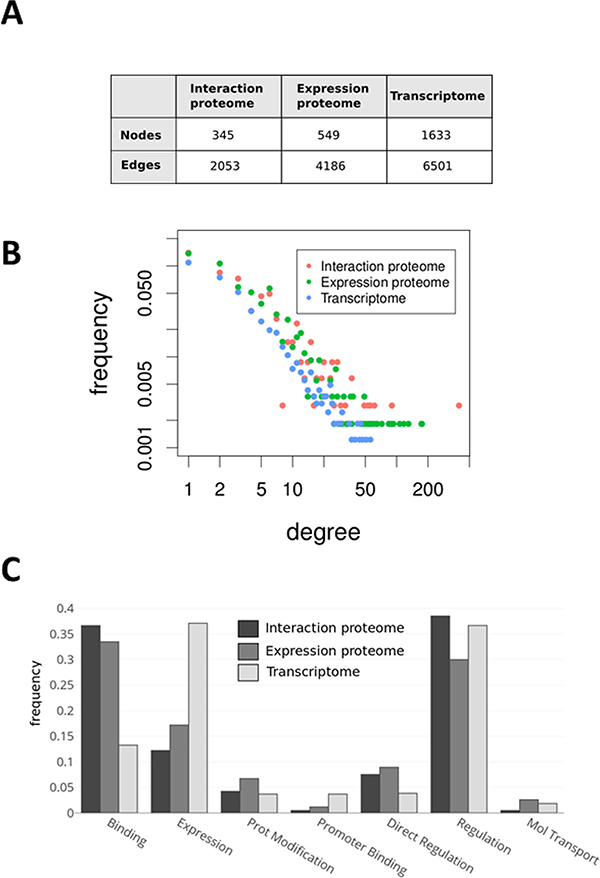

To construct an integrated network combing the transcriptome, expression-proteome, and interaction-proteome data, a combined abundance score19 was computed for each significant node (p value of <0.05) across the three data sets. All direct relations (physical interaction, protein modification, and expression regulation) between the 2623 gene and protein entities in the combined set were used to construct an integrated network using the Pathways Studio database (we hereafter use the terms “edge” to refer to protein–protein relations and “node” to refer to the proteins themselves). To analyze how each of the omics data sets contributes to this integrated network, we computed several network statistics (Figure 4). We observed that the average degree of nodes from each of the three data sets differ within the integrated network (interaction proteome, 5.95; expression proteome, 7.62; transcriptome, 3.98), and we therefore plotted the degree distributions of nodes from each data set as shown (Figure 4B). Nodes within the transcriptome data set have a distinctly lower average degree, attributed to the large fraction of genes and proteins from this data set with few described interactions in the database. The significant enrichment of gene-encoding transcription factors present in the significantly different transcriptome data set contribute toward this difference because, for many of these genes, relatively few interactions have been described. This finding prompted us to investigate whether the types of edges represented in the three data sets differed (Figure 4C). We observe substantial differences in edges annotated as “Binding” in the Pathway Studio database and those annotated as regulating “Expression”, with greater numbers of binding edges in the interaction and expression proteome data sets and substantially more expression edges in the transcriptome data set, indicating the complementarity these different omics datatypes in identifying different types of proteins and edges.

Figure 4.

Network properties of proteomic and transcriptomic data sets. (A) Summary of network properties from the integrated network constructed by integrating all three data sets with known protein–protein interactions. The table indicates the numbers of nodes (protein and genes) and edges (relations between proteins) from each data set integrated into the combined network. (B) Log–log plot of the degree distributions for nodes from each data set (the number of connections for protein nodes typically follow the pattern of interaction proteome > expression proteome > transcriptome). (C) Analysis of interaction (edge) types for each data set indicate significant differences of functional type of edges contributed to the integrated network.

Functional Module Identification and Validation

To focus on specific modules within the integrated network, we curated subnetworks associated with biological pathways or processes that were identified as significantly different between mutant and wild-type cells in the gene set enrichment analysis. Figure 5A shows several selected modules within the integrated network with β-catenin-associated functions. The abundance of proteins indicative of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) were strongly enriched in the mutant cells. We noted that epithelial markers such as claudins and E-cadherin were differentially expressed in the wild-type cells,33 whereas mesenchymal markers such as the cytoskeletal protein vimentin (VIM) are strongly enriched in the mutant cells (VIM was differentially expressed in both the expression-proteome and the transcriptome data sets). In addition, several proteins with functions in tissue remodelling, such as matrix metalloprotease (MMP13) and laminins (LAMB3 and LAMC2), which form the basement membrane required for the attachment and organization of epithelial cells, were identified.

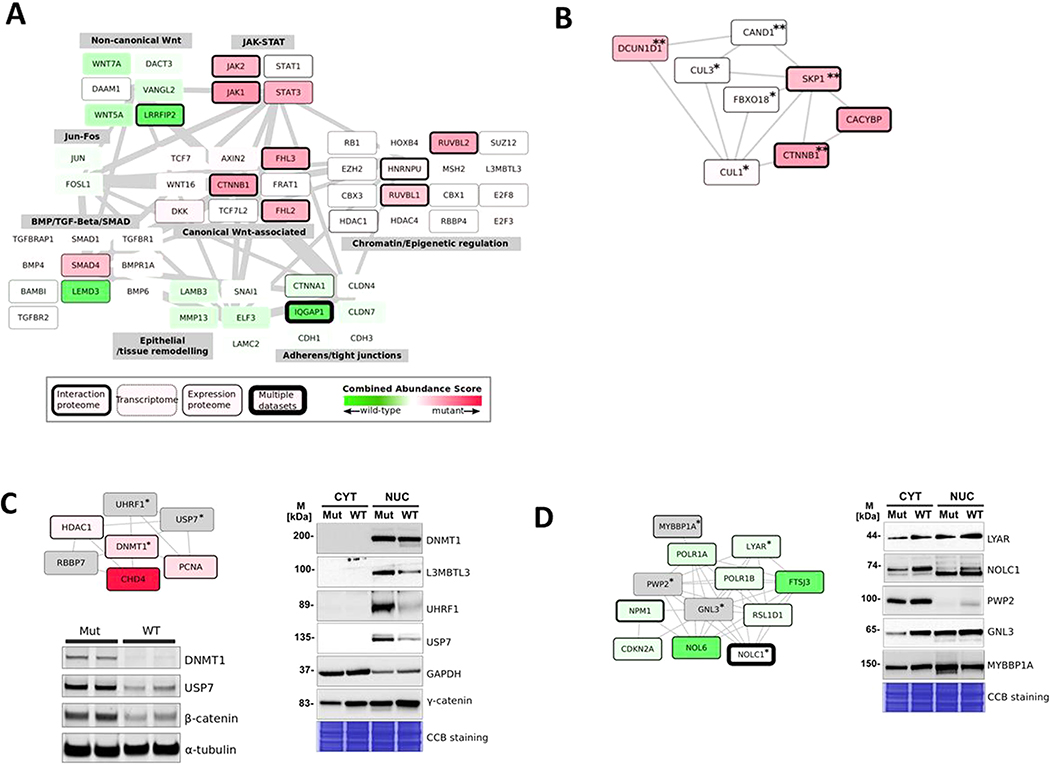

Figure 5.

Integrated proteomic and transcriptomic functional modules. (A) Selected functional modules from the integrated network. Edge thickness represents the overall connectivity between modules (normalized edge weights calculated as the total number of edges divided by the number of genes and proteins in each module). Node (gene and protein) color intensity indicates the combined abundance score (red, mutant; green, wild-type). (B) SCF (Skp-Cullin-F-box)-associated protein network showing proteins significantly (double asterisks indicate p < 0.05; a single asterisk indicates p < 0.1) abundant in interaction- and expression-proteome data sets. (C) DNA methyltransferase I (Dnmt1)-associated protein network. Protein nodes marked with an asterisk were also tested by immunoblotting as shown. Dnmt1, USP7, and β-catenin were tested using immunoblotting on whole-cell lysates from mutant and wild-type cells and additional related interaction partners (UHRF1, L3MBTL3) analyzed by the immunoblotting of nuclear and cytosolic subcellular fractions from mutant and wild-type cells. (D) Western analysis of the ribosome-biogenesis-associated protein network in subcellular fractionated samples. Protein nodes marked with asterisks were also tested by immunoblotting, as shown in nuclear and cytosolic fractions from mutant and wild-type cells as in Figure 5C.

Wild-type cells preferentially expressed proteins implicated in non-canonical Wnt signaling. In addition to the non-canonical Wnt ligands WNT5A and WNT7A, we found that the dishevelled (Dvl)-interacting proteins, DACT3 and DAAM1, were more abundant in the wild-type cells. DACT3 is a member of a family of proteins known to antagonize canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling, suggesting that the process of mutant β-catenin-driven oncogenesis involves the repression of antagonists of canonical signaling. While most components of TGF-β/SMAD and BMP signaling were higher in mutant cells (module 7), we noted that LEMD3, a known antagonist of TGF-β/SMAD signaling was significantly higher in wild-type cells.

Although the integration of transcriptomes and proteomes allowed for increased coverage and representation within functional modules, as shown in Figure 5A, we also observed exclusively proteomic modules.Skp–Cullin–Fbox (SCF) protein complexes are ubiquitin ligase complexes that regulate the ubiquitination of many proteins including β-catenin, and these were uniformly more abundant in mutant cells (Figure 5B). This module was almost uniformly significantly differentially regulated in the proteomic data sets but not in the transcriptomic data set, indicating, in concordance with other findings, that these complexes are mainly regulated at the post-translational level through dynamic rearrangement of protein components.34

We selected two modules for further validation (Figure 5C,D). The primary maintenance DNA methyltransferase (DNMT1) is significantly more abundant in the expression proteome and transcriptome of mutant cells. We analyzed the expression of Dnmt1 and two direct interaction partners of Dnmt1, USP7/HAUSP and UHRF1, and all of these proteins were found to be both nuclear-specific and enriched in mutant cells (Figure 5C). We previously showed that an interaction between β-catenin and the primary DNA methyltransferase, Dnmt1, stabilizes both proteins in the nucleus of cancer cells.35 We previously showed that USP7 regulates the stability of Dnmt1 in cancer cells,36 and UHRF1 has been shown to also participate in the regulation of Dnmt1 stability via ubiquitination. 37 These latest results indicate the coordinated upregulation of Dnmt1–USP7–UHRF1 complexes in mutant cells, linking β-catenin-driven oncogenesis to altered DNA methytransferase activity.

We also noted that one of the most-enriched categories in the gene-enrichment analysis for WT cells were proteins annotated as nucleolar (WT expression proteome data set, p value of 4 × 10−11) and with the related functional annotations of rRNA processing and ribosome biogenesis. We found that many of these proteins formed a highly connected module within the larger integrated network (Figure 5D). Western analysis was used to validate the expression of several proteins that were either significantly differentially abundant in the omics data sets (shaded green) or predicted based upon their connections to other proteins in the module (shaded gray). In addition to their role in ribosome function, several of these proteins have known tumor-suppressing functions. The well-characterized tumor suppressor CDKN2A (P19ARF) is a prominent member of this module and functions to regulate the levels of p53 through its sequestration of MDM2 (a negative regulator of p53)38 in the nucleolus (MDM2 was not identified in the proteomic experiments and not significantly differentially expressed in the transcriptomic experiments). Another protein, nucleostemin (GNL3), that has also been linked to MDM2-p53 regulation39 was differentially more abundant in wild-type cells. We previously identified GNL3 as an interaction partner of LYAR40 and therefore analyzed the expression of this and several other known nucleolar proteins linked to LYAR as shown in Figure 4D, showing their greater abundance in wild-type cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we performed the first multiproteomic and transcriptomic analysis of the molecular response to the stabilization of β-catenin in colorectal cancer cells. We used a cell model of oncogenic β-catenin activity to compare cells expressing a pathogenically and clinically important β-catenin mutation that stabilizes the protein with cells expressing wild-type β-catenin. Global analysis of functional trends showed that mutant cells and mutant β-catenin interactions were enriched in mutant cells, in line with the known importance of the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin for its pathogenic activity. This is in line with the findings presented in the original publication describing these cells, which showed that β-catenin in the mutant cells was more abundant in the nucleus and bound less to E-cadherin than to β-catenin in the wild-type cells, even though the overall abundance of β-catenin in the two cell lines was similar.4

Using integrated proteomic and transcriptomic analyses allowed us to reveal novel functional modules associated with β-catenin-driven oncogenesis. Significantly different expression of multiple Wnt ligand genes was observed between mutant and wild-type cells. WNT2, WNT5A, and WNT7A are significantly higher in the wild-type cells, whereas WNT16 is higher in mutant cells. Wnt5a is the best-studied ligand of this group and is associated with β-catenin-independent or non-canonical Wnt signaling.41 Interestingly, WNT5A can antagonize β-catenin signaling,42 exhibits tumor-suppression activity in colorectal cancer,43 and is associated with subgroups of colorectal cancer patients with good prognosis,44 although WNT5A’s tumor-suppressor properties appear to be limited to certain tumor types.41 We also showed that the expression of DNA methyltransferase I (Dnmt1) and several key Dnmt1 interaction partners are significantly elevated in mutant β-catenin cells, which is consistent with our previous report that β-catenin and Dnmt1 proteins engage in a mutually stabilizing interaction in the nuclei of cancer cells.35 In addition, USP7, which regulates the stability of Dnmt1, has also recently been shown to stabilize β-catenin in colorectal cancer cells expressing APC mutations,45 further linking the regulation of Dnmt1 to β-catenin-driven oncogenesis. Conversely, we identified a module of nucleolar-enriched proteins that were significantly more abundant in wild-type β-catenin cells, including the tumor-suppressor CDKN2A. Expression of CDKN2A is frequently silenced in colorectal and other tumors through promoter hyper-methylation,46 suggesting that alterations of CpG methylation may be induced via oncogenic β-catenin and the greater abundance of DNMT1 and its associated regulators that we observed in cells with mutant β-catenin.

Our study showed how a multiomics approach combining different layers of proteomic and transcriptomic information can reveal more comprehensively how oncoproteins transform molecular networks in cancer cells. Recent studies have shown that, in addition to the mediation of a transcriptional response, the activation of canonical Wnt signaling also acts independently of transcriptional programs to alter protein stabilization,47 necessitating the characterization of oncogenic-mediated effects at proteomic as well as transcriptomic levels. We have adopted the approach of integrating multiomics data with existing network information48 to identify modules within the cellular network that may be perturbed across the multiple layers of transcriptome, expression proteome, or interaction proteome. We observed concerted cellular responses in terms of pathways and processes across these multiple layers. We also showed that these different “layers” of information contribute differentially to the overall analysis of β-catenin-driven oncogenesis by, for example, contributing different types of protein–protein relationship (edges) and identifying proteins with differing network features. In summary, our study both reveals novel biology associated with β-catenin-driven oncogenesis and also illustrates the greater insight that can be gained from applying a systematic multiomics approach.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

R.M.E and Z.W. acknowledge NCI award no. 1R21CA16006 that supported, in part, the work described here. R.M.E acknowledges an EU Marie Curie award (no. FP7-PEOPLE-2012-CIG). This research was supported by the Genomics Core Facility of Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine’s Genetics and Genome Sciences Department.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00180.

A table showing proteins differentially identified between mutant β-catenin and wild-type β-catenin AP-MS experiments. (XLSX)

A table showing a list of canonical Wnt signaling targets. (XLSX)

A table showing a comparison of RNA-Seq data to the previous study. (XLSX)

A table showing peptide, protein, and protein-group lists. (XLS)

A table showing protein sequence database cross-referencing for IPI human v3.72. (PDF)

Figures showing protein abundance (log spectral count values) scatter plots and correlations, the correlation and distribution of fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads, and exemplar protein intensity scatter plots. (PDF)

Table descriptions and a list of references. (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Clevers H Wnt/Beta-Catenin Signaling in Development and Disease. Cell 2006, 127 (3), 469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Amit S; Hatzubai A; Birman Y; Andersen JS; Ben-Shushan E; Mann M; Ben-Neriah Y; Alkalay I Axin-Mediated CKI Phosphorylation of Beta-Catenin at Ser 45: A Molecular Switch for the Wnt Pathway. Genes Dev. 2002, 16 (9), 1066–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Morin PJ; Sparks AB; Korinek V; Barker N; Clevers H; Vogelstein B; Kinzler KW Activation of Beta-Catenin-Tcf Signaling in Colon Cancer by Mutations in Beta-Catenin or APC. Science 1997, 275 (5307), 1787–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Valenta T; Hausmann G; Basler K The Many Faces and Functions of β-Catenin. EMBO J. 2012, 31 (12), 2714–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Angers S; Moon RT Proximal Events in Wnt Signal Transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Cadigan KM TCFs and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling: More than One Way to Throw the Switch. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2012, 98, 1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Song J; Wang Z; Ewing RM Integrated Analysis of the Wnt Responsive Proteome in Human Cells Reveals Diverse and Cell-Type Specific Networks. Mol. BioSyst. 2014, 10 (1), 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Tian Q Proteomic Exploration of the Wnt/Beta-Catenin Pathway. Curr. Opin Mol. Ther 2006, 8 (3), 191–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Gujral TS; MacBeath G A System-Wide Investigation of the Dynamics of Wnt Signaling Reveals Novel Phases of Transcriptional Regulation. PLoS One 2010, 5 (4), 10024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hilger M; Mann M Triple SILAC to Determine Stimulus Specific Interactions in the Wnt Pathway. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Acebron SP; Karaulanov E; Berger BS; Huang Y-L; Niehrs C Mitotic Wnt Signaling Promotes Protein Stabilization and Regulates Cell Size. Mol. Cell 2014, 54 (4), 663–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Jho E; Zhang T; Domon C; Joo C-K; Freund J-N; Costantini F Wnt/Beta-Catenin/Tcf Signaling Induces the Transcription of Axin2, a Negative Regulator of the Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22 (4), 1172–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Niida A; Hiroko T; Kasai M; Furukawa Y; Nakamura Y; Suzuki Y; Sugano S; Akiyama T DKK1, a Negative Regulator of Wnt Signaling, Is a Target of the [Beta]-Catenin//TCF Pathway. Oncogene 2004, 23 (52), 8520–8526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Chan TA; Wang Z; Dang LH; Vogelstein B; Kinzler KW Targeted Inactivation of CTNNB1 Reveals Unexpected Effects of Beta-Catenin Mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99 (12), 8265–8270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Song J; Hao Y; Du Z; Wang Z; Ewing RM Identifying Novel Protein Complexes in Cancer Cells Using Epitope-Tagging of Endogenous Human Genes and Affinity-Purification Mass Spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11 (12), 5630–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Nesvizhskii AI; Keller A; Kolker E; Aebersold R A Statistical Model for Identifying Proteins by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75 (17), 4646–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kim D; Pertea G; Trapnell C; Pimentel H; Kelley R; Salzberg SL TopHat2: Accurate Alignment of Transcriptomes in the Presence of Insertions, Deletions and Gene Fusions. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Anders S; Pyl PT; Huber W HTSeq—a Python Framework to Work with High-Throughput Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31 (2), 166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Balbin OA; Prensner JR; Sahu A; Yocum A; Shankar S; Malik R; Fermin D; Dhanasekaran SM; Chandler B; Thomas D Reconstructing Targetable Pathways in Lung Cancer by Integrating Diverse Omics Data. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chen EY; Tan CM; Kou Y; Duan Q; Wang Z; Meirelles GV; Clark NR; Ma’ayan A Enrichr: Interactive and Collaborative HTML5 Gene List Enrichment Analysis Tool. BMC Bioinf. 2013, 14, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kwon AT; Arenillas DJ; Worsley Hunt R; Wasserman WW oPOSSUM-3: Advanced Analysis of Regulatory Motif over-Representation across Genes or ChIP-Seq Datasets. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genet. 2012, 2 (9), 987–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Zhao M; Sun J; Zhao Z TSGene: A Web Resource for Tumor Suppressor Genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41 (D1), D970–D976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Chen J-S; Hung W-S; Chan H-H; Tsai S-J; Sun HS In Silico Identification of Oncogenic Potential of Fyn-Related Kinase in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Bioinformatics 2013, 29 (4), 420–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lin SY; Xia W; Wang JC; Kwong KY; Spohn B; Wen Y; Pestell RG; Hung MC Beta-Catenin, a Novel Prognostic Marker for Breast Cancer: Its Roles in Cyclin D1 Expression and Cancer Progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97 (8), 4262–4266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Herbst A; Jurinovic V; Krebs S; Thieme SE; Blum H; Göke B; Kolligs FT Comprehensive Analysis of β-Catenin Target Genes in Colorectal Carcinoma Cell Lines with Deregulated Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Mokry M; Hatzis P; Schuijers J; Lansu N; Ruzius F-P; Clevers H; Cuppen E Integrated Genome-Wide Analysis of Transcription Factor Occupancy, RNA Polymerase II Binding and Steady-State RNA Levels Identify Differentially Regulated Functional Gene Classes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40 (1), 148–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Buck A; Buchholz M; Wagner M; Adler G; Gress T; Ellenrieder V The Tumor Suppressor KLF11 Mediates a Novel Mechanism in Transforming Growth Factor Beta-Induced Growth Inhibition That Is Inactivated in Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2006, 4 (11), 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ghaleb AM; Elkarim EA; Bialkowska AB; Yang VW KLF4 Suppresses Tumor Formation in Genetic and Pharmacological Mouse Models of Colonic Tumorigenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016, 14, 385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zhao W; Hisamuddin IM; Nandan MO; Babbin BA; Lamb NE; Yang VW Identification of Krüppel-like Factor 4 as a Potential Tumor Suppressor Gene in Colorectal Cancer. Oncogene 2004, 23 (2), 395–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Zhang W; Chen X; Kato Y; Evans PM; Yuan S; Yang J; Rychahou PG; Yang VW; He X; Evers BM; et al. Novel Cross Talk of Kruppel-like Factor 4 and Beta-Catenin Regulates Normal Intestinal Homeostasis and Tumor Repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26 (6), 2055–2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Evans PM; Chen X; Zhang W; Liu C KLF4 Interacts with Beta-Catenin/TCF4 and Blocks p300/CBP Recruitment by Beta-Catenin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30 (2), 372–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Shah M; Rennoll SA; Raup-Konsavage WM; Yochum GS A Dynamic Exchange of TCF3 and TCF4 Transcription Factors Controls MYC Expression in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Cell Cycle Georget. Cell Cycle 2015, 14 (3), 323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Gonzalez DM; Medici D Signaling Mechanisms of the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Sci. Signaling 2014, 7 (344), re8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Pierce NW; Lee JE; Liu X; Sweredoski MJ; Graham RLJ; Larimore EA; Rome M; Zheng N; Clurman BE; Hess S; et al. Cand1 Promotes Assembly of New SCF Complexes Through Dynamic Exchange of F-Box Proteins. Cell 2013, 153 (1), 206–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Song J; Du Z; Ravasz M; Dong B; Wang Z; Ewing RM A Protein Interaction between -Catenin and Dnmt1 Regulates Wnt Signaling and DNA Methylation in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13 (6), 969–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Du Z; Song J; Wang Y; Zhao Y; Guda K; Yang S; Kao H-Y; Xu Y; Willis J; Markowitz SD; et al. DNMT1 Stability Is Regulated by Proteins Coordinating Deubiquitination and Acetylation-Driven Ubiquitination. Sci. Signaling 2010, 3 (146), ra80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Qin W; Leonhardt H; Pichler G Regulation of DNA Methyltransferase 1 by Interactions and Modifications. Nucl. Austin Tex 2011, 2 (5), 392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Stott FJ; Bates S; James MC; McConnell BB; Starborg M; Brookes S; Palmero I; Ryan K; Hara E; Vousden KH; et al. The Alternative Product from the Human CDKN2A Locus, p14(ARF), Participates in a Regulatory Feedback Loop with p53 and MDM2. EMBO J. 1998, 17 (17), 5001–5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Tsai RYL Turning a New Page on Nucleostemin and Self-Renewal. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127 (18), 3885–3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ewing RM; Chu P; Elisma F; Li H; Taylor P; Climie S; McBroom-Cerajewski L; Robinson MD; O’Connor L; Li M; et al. Large-Scale Mapping of Human Protein-Protein Interactions by Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007, 3, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kikuchi A; Yamamoto H; Sato A; Matsumoto S Wnt5a: Its Signalling, Functions and Implication in Diseases. Acta Physiol. 2012, 204 (1), 17–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).van Amerongen R; Fuerer C; Mizutani M; Nusse R Wnt5a Can Both Activate and Repress Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling during Mouse Embryonic Development. Dev. Biol. 2012, 369 (1), 101–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Ying J; Li H; Yu J; Ng KM; Poon FF; Wong SCC; Chan ATC; Sung JJY; Tao Q WNT5A Exhibits Tumor-Suppressive Activity through Antagonizing the Wnt/Beta-Catenin Signaling, and Is Frequently Methylated in Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14 (1), 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Dejmek J Wnt-5a Protein Expression in Primary Dukes B Colon Cancers Identifies a Subgroup of Patients with Good Prognosis. Cancer Res. 2005, 65 (20), 9142–9146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Novellasdemunt L; Foglizzo V; Cuadrado L; Antas P; Kucharska A; Encheva V; Snijders AP; Li VSW USP7 Is a Tumor-Specific WNT Activator for APC-Mutated Colorectal Cancer by Mediating β-Catenin Deubiquitination. Cell Rep. 2017, 21 (3), 612–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Baylln SB; Herman JG; Graff JR; Vertino PM; Issa JP Alterations in DNA Methylation: A Fundamental Aspect of Neoplasia. Adv. Cancer Res. 1997, 72, 141–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Acebron SP; Niehrs C β-Catenin-Independent Roles of Wnt/LRP6 Signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Joyce AR; Palsson BØ The Model Organism as a System: Integrating “Omics” Data Sets. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7 (3), 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.