Abstract

Background:

There is a dearth of national and international data on the impact of social support on physical, mental, and financial outcomes following bereavement.

Methods:

We draw from two large, population-based studies of bereaved people in Australia and Ireland to compare bereaved people’s experience of support. The Australian study used a postal survey targeting clients of six funeral providers and the Irish study used telephone interviews with a random sample of the population.

Results:

Across both studies, the vast majority of bereaved people reported relying on informal supporters, particularly family and friends. While sources of professional help were the least used, they had the highest proportions of perceived unhelpfulness. A substantial proportion, 20% to 30% of bereaved people, reported worsening of their physical and mental health and about 30% did not feel their needs were met. Those who did not receive enough support reported the highest deterioration in wellbeing.

Discussion:

The compassionate communities approach, which harnesses the informal resources inherent in communities, needs to be strengthened by identifying a range of useful practice models that will address the support gaps. Ireland has taken the lead in developing a policy framework providing guidance on level of service provision, associated staff competencies, and training needs.

Keywords: bereavement support, mental health, physical health, professional support, social support, sources of support, wellbeing, compassionate communities

Background

Bereavement is a universal experience that inevitably affects everyone at some point, and typically many times, over the life course. For many people, the intensity of grief subsides over time as grievers adapt and accommodate the loss into their everyday lives. A considerable minority of grievers, about 6% to 8%, experience intense, persistent, and disabling grief that meets the criteria of a mental disorder,1,2 recognised as Prolonged Grief Disorder.3 Thus, bereavement represents a major health and economic challenge.4–6

In recent decades, there has been much research on the health sequelae of disordered grief,7 with less attention paid to the majority of grievers. Much of what is known is based on studies of informal caregivers. These caregivers are central to the provision of end-of-life care, yet investigating the effects of caregiving and bereavement is an emerging area, with some methodological limitations. What is known is that pre-death grief appears to have a stronger association with post-death grief8,9 than do demographic factors.10,11 However, these studies typically don’t include social factors.

Reviews of factors that are associated with grief outcomes indicate that social support is one of the strongest determinants of positive psychosocial outcomes after bereavement12,13; social support is also one of the few that is modifiable after bereavement.14 A recent study of a very large cohort of Australians compared the health-related quality of life of people bereaved by the death of one or more close friends (n = 9586) to those who had not experienced this loss (n = 16,929).15 After controlling for potential confounding variables, the authors demonstrated adverse and enduring physical, psychological, and social outcomes. Importantly, these deleterious outcomes were more likely for bereaved people reporting lower levels of social activity, demonstrating the role that social connectedness plays in bereavement outcomes.

However, there is a dearth of national and international data on the impact of social support on physical, mental, and financial outcomes. We draw from two large studies of bereaved people – one in Australia, one in Ireland – to compare bereaved people’s experience of support in the two countries. Specifically, the study had the following objectives.

Objectives

To compare the self-reported physical, mental, and financial impact of the most recent bereavement in the last 2 years from the date of the survey in Australia and Ireland.

To determine who provides bereavement support in the community in the two countries.

To determine the extent to which the support was perceived sufficient to meet the needs of the bereaved.

To identify what sources of support were perceived to be the most or least helpful.

Methods

Study design

The Australian study was a population-based cross-sectional investigation of bereavement experiences (see Aoun and colleagues,1 for the initial results of the study, based on data from four funeral providers in the states of Victoria and Western Australia). A postal survey was used to collect information from clients of six funeral providers in Australia, 6 to 24 months after the death of their family member. We chose this time period as 6 months post-bereavement is the earliest time period required for diagnosis of Prolonged Grief Disorder while 24 months is not likely to compromise the accuracy of recalled information. Funeral providers were used as it was not possible to recruit through the Death Registry.

This study in Ireland was based on a population-based cross-sectional study of bereavement experiences and entailed a telephone survey of a random sample of 908 adults (18+ years) living in the Republic of Ireland. The majority surveyed (n = 767, 85%) reported being bereaved of someone close at some point in their life. Only the data from those who were bereaved within the previous 2 years at the time of the survey (n = 218, 37%) were included in the analyses reported here for appropriate comparison with the Australian data.

Participants and procedures

A total of 6258 study packages were delivered to the six Australian funeral providers in the states of Victoria, Western Australia, New South Wales, and Tasmania (2014-2016). These packages included an invitation letter addressed from the funeral provider to the family, information sheet, the questionnaire, a list of support services for the family to use in case the participant became distressed while completing the questionnaire, and a reply-paid envelope. Clients who were bereaved 6 to 24 months ago were selected by funeral providers from their databases, who affixed names and address labels on the envelopes and posted the study packages. Return of the completed survey was considered implied consent. It was considered insensitive to send a reminder letter to the bereaved families. Clients were eligible to participate in the study if they had been bereaved by a close family member or friend in the specified timeframe, were over 18 years old and were able to read, understand, and write in English.

The telephone interviews in Ireland were carried out by Amárach Research in September 2016 as part of their regular syndicated telephone omnibus survey. The respondents were accessed from a panel of over 40,000 potential respondents, using strict quotas, which were imposed by sex, age, and region, to ensure the sample was statistically representative of the Irish adult population. The participants were informed of the nature of the study from the outset of the survey and given an option to opt out at any stage of the interview process. The respondents were also given details of an independent counselling service if they wished to discuss any issues raised in the survey. None did. Unlike the Australian sample which targeted a bereaved sample, the Irish study accessed a population based sample so the time since death at the time of the survey varied (<3 months: 8%; 3-6 months: 6%; 6-12 months: 7%; 1-2 years: 16%; >2 years: 63%).

Materials

The Australian questionnaire was developed to obtain demographic information, the supports people accessed, supports they would have liked to have been able to access, their perceived needs, and whether they were met. It had 8 sections with a total of 82, predominantly closed questions. The questionnaire was developed in consultation with a reference group comprising representatives of the funeral industry, bereavement counsellors, palliative care services, primary care, and community-based services.1,16

The Irish questionnaire included items on attitudes to death, dying, and bereavement used in previous Irish surveys and many of the questions had been included in an earlier survey commissioned by the Irish Hospice Foundation. In addition, nine questions relating to bereavement experiences used by the Australian population-based postal survey were included.1

The present article focuses on the questions used in both surveys, in the last 2 years from survey date: demographic information, the nature of the relationship between the bereaved and the deceased, the time since the death, experience of physical, mental, and financial wellbeing since the death; specific types of support accessed and their helpfulness, support that may have been missing and the overall adequacy of support received. The supports bereaved people received were grouped into professional, community, and informal. Professional support included support offered by trained counsellors, bereavement support groups, social workers, case coordinators, psychologists, and psychiatrists. Community support included support offered by general physicians (GPs), nursing homes, hospitals, pharmacists, community groups, palliative care providers, or school-based advisors. Informal support included support offered by family, friends, funeral directors, financial or legal advisors, religious or spiritual advisors, the Internet, or literature.1

Ethics approvals

Ethics approval for the Australian study was granted by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HR-57/2012). In Ireland, the survey was evaluated by the Research Ethics Committee (Sciences) of University College Dublin, and it was accepted as an Exemption for full ethical approval, provided best ethical practice was applied. In Ireland, the participants were informed of the nature of the survey from the outset of the survey and given an option to opt out at any stage of the interview process. The respondents were also given details of an independent counselling service if they wished to discuss any issues raised in the survey. None availed of this. In Australia, recipients were provided in the survey package with a comprehensive list of appropriate services and contact details should they become distressed.

Analysis

The data were analysed using IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 24). Descriptive and inferential statistics were conducted with frequencies calculated for the categorical variables and significance testing performed using chi-square. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

The response rates ranged from 13.3% to 28.6% among the six Australian funeral providers, with an average response rate of 18.2%. This yielded 1139 completed responses, of which 839 were eligible for analysis as the remainder fell outside the bereavement period of 6–24 months. 84% of the Irish sample had been bereaved of someone close and of these 37% (n = 281) had been bereaved within the previous 2 years and these are the ones being compared to the Australian sample.

Profile of the bereaved

In the Australian survey, the mean age of respondents was 63 years with 78% aged 55 years and older, 71% were female, 50% were married/de facto and 36% widowed, 45% were retired and 40% in paid employment, and 35% lost a partner and 48% lost a parent (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of those bereaved in the last two years in Australia and Ireland.

| Australia (839) |

Ireland (281) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 240 | 28.7 | 146 | 52 |

| Female | 597 | 71.3 | 135 | 48 |

| Missing | 2 | |||

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18-24 years | 1 | 0.1 | 51 | 18 |

| 25-34 years | 12 | 1.4 | 51 | 18 |

| 35-44 years | 34 | 4.1 | 56 | 20 |

| 45-54 years | 138 | 16.7 | 41 | 15 |

| 55+ years | 643 | 77.7 | 82 | 29 |

| Missing | 11 | |||

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married or single | 41 | 4.9 | 74 | 26 |

| Married or de facto | 418 | 50.1 | 171 | 61 |

| Separated or divorced | 77 | 9.2 | 26 | 9 |

| Widowed | 298 | 35.7 | 10 | 4 |

| Main employment | ||||

| Paid employment | 331 | 39.8 | 218 | 78 |

| Retired, volunteer | 373 | 44.8 | 29 | 10 |

| Disabled | 13 | 1.6 | - | - |

| Household duties | 99 | 11.9 | 11 | 4 |

| Unemployed | 12 | 1.4 | 14 | 5 |

| Other | 47 | 0.5 | 9 | 3 |

| Period of bereavement (months) | ||||

| <6 months | 0 | 0.0 | 110 | 39 |

| 6-12 months | 306 | 36.5 | 51 | 18 |

| 13-18 months | 295 | 35.2 | 120 | 43 |

| 19-24 months | 238 | 28.4 | ||

| Relationship to the deceased | ||||

| Wife/husband or partner | 290 | 34.6 | 10 | 4 |

| Girlfriend/boyfriend | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1 |

| Mother/father | 51 | 6.1 | 10 | 4 |

| Sister/brother | 31 | 3.7 | 35 | 13 |

| Daughter/son | 403 | 48.1 | 42 | 15 |

| Other relative | 45 | 5.4 | 117 | 42 |

| Friend | 16 | 1.9 | 60 | 21 |

| Other | 2 | 0.2 | ||

In the Irish survey, the gender was almost equal between males and females. The majority of respondents in Ireland are other relative and friend (total 63%) and the age is stratified to have equal proportions in each age group, thus 29% are 55 years and over. By comparison in Australia, most respondents are spouses or adult children (total 82.7%) (Table 1).

Self-reported impact of bereavement

Participants’ responses demonstrated a multi-faceted impact of bereavement in Australia and Ireland, with 26% and 27%, respectively, reporting a deterioration in physical health and 27% and 35%, respectively, reporting a deterioration in mental health after the death. In addition, 17% to 19% experienced a decline in their financial situation (Table 2). Conversely, some reported that their financial situation (26% in Australia; 11% in Ireland), physical health (11%, 10%), and mental health (14%, 8%) improved following bereavement.

Table 2.

Respondents’ self-reported physical and mental health and financial situation since relative/ friend died (N, %).

| Australia, n = 839 |

Ireland, n = 281 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical health |

Mental health |

Financial situation |

Physical health |

Mental health |

Financial situation |

|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Improved | 90 (10.8) | 119 (14.3) | 218 (26.1) | 27 (10) | 23 (8) | 31 (11) |

| Stayed the same | 529 (63.3) | 491 (58.8) | 475 (56.8) | 178 (63) | 162 (58) | 197 (70) |

| Got a bit worse | 181 (21.7) | 178 (21.3) | 109 (13.0) | 65 (23) | 80 (29) | 38 (14) |

| Got a lot worse | 36 (4.3) | 47 (5.6) | 34 (4.1) | 10 (4) | 16 (6) | 14 (5) |

Participants who reported deterioration in one aspect of wellbeing (i.e. physical health, mental health, and financial situation) were more likely to report deterioration in another aspect of wellbeing. In particular, those who reported deterioration in physical health were more likely to report deterioration in their mental health (with large effect sizes), 89% in Australia (Cramer’s V = 0.542, P < .0001) and 67% in Ireland (Cramer’s V = 0.421, P < .0001).

Sources of support after bereavement

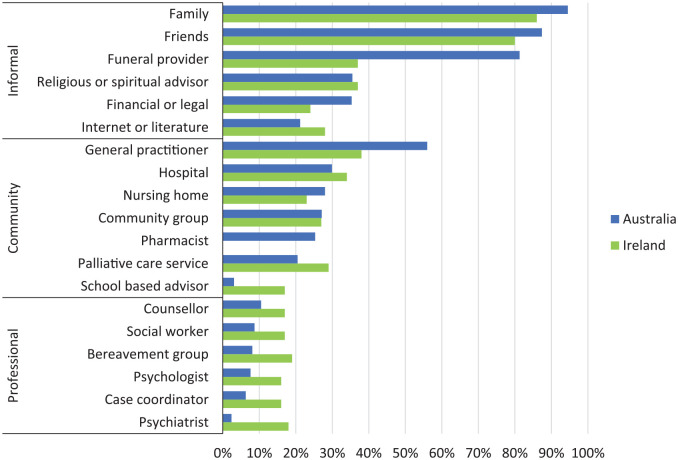

Sources of support are illustrated in Figure 1 and are indicated as ‘informal’, ‘community’ and ‘professional’ supports, following the categorisation by Aoun and colleagues. As might be expected, the majority of bereaved people reported that family (94% Australia and 86% Ireland) and friends (88% Australia and 80% Ireland) as sources of support as well as to those most likely to be present at/close to the time of a death such as the funeral director (82% in Australia and 37% in Ireland), or priest/spiritual advisor (36% in Australia and 37% in Ireland). At a community level, health structures were evident with relatively large proportions accessing support from GPs (56% in Australia and 38% in Ireland), hospitals (30% in Australia and 34% in Ireland), palliative care services (20% in Australian and 29% in Ireland), or nursing homes (28% in Australia and 23% in Ireland). The proportion of those who accessed professional bereavement support from mental health professionals or bereavement support groups ranged from 5% to 10% in Australia and 16% to 19% in Ireland.

Figure 1.

Sources of bereavement support accessed in Australia and Ireland.

More respondents in Ireland had accessed palliative care services (30% vs 20%), school-based advisors (17% vs 3%), and professional services (16%-19%; 5%-10%) for bereavement support compared to Australia. While more respondents in Australia had accessed family (95% vs 86%), funeral providers (81% vs 37%), and GPs (56% vs 38%) when compared to Ireland (Figure 1).

The helpfulness of sources of support

The extent to which these sources of support were actually rated as ‘helpful’ varied. In Australia, while the professional category sources were the least used, and used less than in Ireland, they had the highest proportions of perceived unhelpfulness: Half of those who used psychiatrists found them unhelpful (50%), and about 40% of respondents who used the following professional services rated them unhelpful: Bereavement support group (37%), case coordinator (42%), social worker (44%), and school based advisor (42%). Similar high rates of unhelpfulness were reported in the community category and in particular a community group (37%), community pharmacist (38%), and palliative care service (32%). By contrast, the lowest proportions of unhelpfulness were in the informal category where only 10% found family and funeral providers unhelpful, followed by friends (12%) (Figure 2(a)).

Figure 2.

(a) Sources of support accessed and perceived as helpful or unhelpful in Australia. (b) Sources of support accessed and perceived as helpful or unhelpful in Ireland.

In Ireland, like Australia, the sources rated most ‘helpful’ included family (84%), friends (80%), and funeral provider (76%). Although most rated support from family and friends as helpful, some found this support unhelpful (16% and 20%, respectively). More respondents rated the remaining informal supports (55%-61%), the community supports (54% to 68%), and the professional supports (53%-63%) as helpful than not helpful. However, more respondents rated community groups as unhelpful (53%) than helpful (Figure 2(b)).

Both countries rated the helpfulness of the support from the hospital, palliative care, social work, bereavement groups, psychiatrist, and the Internet quite similar. However, more respondents in Australia rated some informal supports (family, friends, funeral director), community supports (GP, community groups, nursing homes) and professional supports (counsellor, psychologist, case coordinator) more helpful when compared to respondents in Ireland.

Perceived sufficiency of received support

In all, 65% of the bereaved respondents in Australia and 58% in Ireland felt that they received as much support as they needed. However, almost one third (29% in Australia and 32% in Ireland) reported that they were not fully supported in their bereavement (either they got some support but not as much as they needed, they did not get the support they would have liked and tried to get more help, or they did not get the support they would have liked but they did not ask for more help) (Figure 3). A further 8% to 10% stated that they did not need help.

Figure 3.

Sufficiency of support in Australia and Ireland.

Receiving sufficient support after the death significantly impacted on self-reported wellbeing (i.e. physical health, mental health, and financial situation). Those who did not receive enough support reported the highest deterioration in wellbeing when compared to those who felt they received sufficient support (P < .001), with small to medium effect sizes (Figure 4(a)–(c), Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Sufficiency of support and self-reported physical wellbeing: Australia and Ireland. (b) Sufficiency of support and self-reported mental wellbeing: Australia and Ireland. (c). Sufficiency of support and self-reported financial wellbeing: Australia and Ireland.

Table 3.

Sufficient support and wellbeing after bereavement in Australia (N, %).

| Physical health |

Mental health |

Financial health |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved/Same |

Got worse |

Improved/Same |

Got worse |

Improved/Same |

Got worse |

|||||||

| n | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | n | % | |

| Enough support | 430 | 81.6 | 97 | 18.4 | 431 | 81.8 | 96 | 18.2 | 453 | 86.0 | 74 | 14.0 |

| Not enough support | 124 | 54.1 | 105 | 45.9 | 114 | 50.0 | 114 | 50.0 | 170 | 73.9 | 60 | 26.1 |

| Did not need support | 46 | 82.1 | 10 | 17.9 | 45 | 80.4 | 11 | 19.6 | 49 | 89.1 | 6 | 10.9 |

| P-value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||||||||

| Effect size | 0.282 | 0.320 | 0.149 | |||||||||

Fisher’s Exact test for 3x2 contingency tables.

Bereavement support vs Physical health: Cramer’s V, small-medium effect size.

Bereavement support vs Mental health: Cramer’s V, medium effect size.

Bereavement support vs Financial health: Cramer’s V, small effect size.

Table 4.

Sufficient support and wellbeing after bereavement in Ireland (N, %).

| Physical health |

Mental health |

Financial health |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved/Same |

Got worse |

Improved/Same |

Got worse |

Improved/Same |

Got worse |

|||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Enough support | 132 | 83 | 27 | 17 | 122 | 76.7 | 37 | 23.3 | 136 | 85.5 | 23 | 14.5 |

| Not enough support | 45 | 50.6 | 44 | 49.4 | 37 | 41.1 | 57 | 58.9 | 63 | 70.8 | 26 | 29.2 |

| Did not need support | 26 | 92.9 | 2 | 7.1 | 24 | 85.7 | 4 | 14.3 | 25 | 89.3 | 3 | 10.7 |

| P-value | <.001 | <.001 | .009 | |||||||||

| Effect size | 0.365 | 0.37 | 0.185 | |||||||||

Fisher’s Exact test for 3x2 contingency tables.

Bereavement support vs Physical health: Cramer’s V, small-medium effect size.

Bereavement support vs Mental health: Cramer’s V, medium effect size.

Bereavement support vs Financial health: Cramer’s V, small effect size.

In all, 46% to 49% of those who did not receive enough support experienced worsening of their physical health compared to 18% to 17% of those who did receive enough support (Figure 4(a)). Higher proportions of the bereaved who did not receive enough support reported worsening mental health (50%-59%) compared to those who did receive enough support (18%-23%) (Figure 4(b)). Financial wellbeing was the least affected although the differences between the two groups were also significant (Figure 4(c)).

Discussion

This comparative study was valuable in identifying similarities or differences in the bereavement experience between two English-speaking countries though in two different continents. Currently, there are no national standards for bereavement service provision in either Ireland or Australia. As a result, bereavement care varies across settings and locations.17 Service provision is more structured in some settings due to the introduction of standards or guidelines, such as palliative care, hospice settings, and maternity services. The majority of bereavement care is provided by voluntary organisations and relies on the ability of the organisation to raise awareness of their services among possible referral sources and the public.18 Statutory mental health services are in charge with dealing with severe complications of grieving.

Despite the different recruitment methodologies in the two studies and the different age distribution of the bereaved and their relationship to the deceased, the vast majority of bereaved people relied on informal supporters, particularly family and friends, than community or professional support. This is in line with a public health approach to bereavement support.1

Impact of bereavement

The study confirmed, through self-report, that the majority of people adapt in bereavement19 with two-thirds reporting that their physical, mental, and financial circumstances stayed the same. Nevertheless, a substantial proportion, between 20% and 30%, reported worsening of these aspects of quality of life. Those reporting their mental health ‘got a lot worse’ (5.6% in Australia, 6% in Ireland) aligns with the proportion (6.4%) identified as ‘high-risk’ group and in need of more support.1 Similarly, they are in line with the most recent prevalence for population levels of prolonged grief established in Germany2 and in an international systematic review and meta-analysis.20

A relationship between self-reported post-bereavement mental and physical health and perceived support during bereavement was observed. Those who rated their health as deteriorated also attested a lack of support in bereavement. This relationship is likely to reflect a complexity of issues and cannot be viewed as causal. However, it is clear that a considerable proportion of bereaved people experience isolation/lack of support and poor health, which they connect to the experience of being bereaved.21–23

Sources of support and their perceived helpfulness

Aoun and colleagues1 concluded that, apart from everyone needing informal support from their social networks, more than two-fifths of people required some other form of bereavement support (35% community and 6% professional). More centrally, they noted that those most at risk of complications in grieving were accessing formal professional services and those at moderate risk were accessing community-based services. While standardised grief measurements were not used in the current comparative study, there are clear indications that help was being sought at community and professional level by relatively large proportions of bereaved people. If the trend in help-seeking follows, Aoun and colleagues’s observation that those seeking help from professional services are those most in need, then it is concerning to see the quality or perceived effectiveness of help rated as low. We may extrapolate either that people are not receiving best bereavement care or people’s expectations of what is helpful is not reflected in the services. In fact, a closer analysis of respondents who used palliative care services24 showed that just half of the bereaved had a follow-up contact from the palliative care services at 3 to 6 weeks, and only a quarter had a follow-up at 6 months and that the blanket non-tailored approach to bereavement support adopted by the services was deemed unhelpful by survey respondents.24

Respondents rated professional supports, such as counsellors, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers poorly. A systematic review of studies assessing professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and/or training regarding grief and complicated grief highlighted training deficits in bereavement in general,25 either related to lack of exposure to evidence-based grief information or relying on old-fashioned and unproductive models used with bereaved clients.26,27 Also higher expectations of what care professionals should offer could be reflected in higher dissatisfaction levels. However, it is worth noting that inappropriate referrals for intervention may lead to worse outcomes in bereavement.28,29 The possibility of grief to be seen as a problem that requires only professional intervention30 may compromise the support that could be offered by existing networks and this could be triggered by early and unrequested referrals to counsellors.

In Australia, funeral providers were the third most prevalent form of bereavement support after friends and family and only 10% of them were deemed unhelpful. Aoun and colleagues31 concluded that, in addressing community needs, funeral providers can play a crucial role in bolstering community capacity around death, dying and bereavement. However, respondents have sought more support from funeral providers in Australia (82%) than in Ireland (38%), possibly because in Australia as less religion is practised than Ireland, the funeral providers may have taken the place of religious leaders. In fact, it is reported in the literature that there are indications that in Western countries, religious figures have essentially been replaced by funeral providers as sources of professional support on death-related matters.32 However even in Ireland, 75% of bereaved respondents were satisfied with the support received from funeral providers. As reported in other studies,1,21 we are not certain if they are providing ongoing support or whether the nature and extent of their dealings shortly after death has a durable positive impact.

Given the largest proportion of bereavement care occurs in communities, rather than professional settings, it is important to note that, in the Irish study, 20% rated support from family and friends as ‘not or a little helpful’, while it was only about 8% to 10% in Australia. Other supports in the community in both countries, such as GP, nursing homes, hospitals, community groups and school-based advisors, were rated relatively poorly. It is suggested that few protective factors in bereavement can be modified to the extent that social support can.14 Both professional and public understandings of bereavement are often based on old theoretical models (eg, Kubler-Ross’s five stages) and guided by social norms or rules which set out what is ‘appropriate’ in terms of progress in grief.33 Consequently, subjective grief experiences which do not match these prescriptions may be even more confusing or isolating for the mourner who feels their grief is outside of ‘normal’ experience.34

Perceived sufficiency of support

It is noteworthy that in the two studies the proportion of 29% to 32% of people who did not feel their needs were met, were also likely to have sought or accessed help from more sources. This group is of particular concern as they were more likely to report deterioration in mental and physical health and their financial situation. They accessed family and friends but were more likely to find this support less helpful and thus more likely to access other formal supports. Aoun and colleagues1 found that those most at risk of complications in their grieving were more likely to perceive a lack of support when compared to moderate and low risk groups. Thus, this subgroup may be at risk of a complicated grief. This highlights the importance of community-based approaches. There are number of growing initiatives to raise awareness of grief and grief reactions and improve community capacity to provide timely and appropriate bereavement care. Community initiatives, like compassionate community projects, enhance the natural supporters of grief through improving perceptions of and attitudes towards death, dying and bereavement, and harnessing the informal resources inherent in communities.35–37

What is interesting is that, despite the different recruitment methodologies in the two studies and by consequence the different age distribution of the bereaved and their relationship to the deceased, the impact of the perceived insufficiency of support on health deterioration is very similar, just slightly higher in Ireland where the cohort with very recent bereavement in the last 6 months was included in the analysis (39% of total). The majority of the bereaved in Ireland were other relative and friend (total 63%) and the age is stratified to have equal proportions in each age group and hence only 29% were 55 years and over. By comparison in Australia, most respondents were spouses or adult children (total 82.7%) who we assume would have had more hands-on care than a more distant relative or a friend and 78% were 55 years and over. However, support may be perceived as insufficient for a number of reasons. It may not actually have been offered because a loss has not been recognised/acknowledged by others, and a person experiences a disenfranchised grief.38 This may come into play for the category of ‘other relative’ and ‘other’ and as Robson and Walter39 noted there is a popular tendency to work to a hierarchy of grief. Alternatively, support may have been offered, but it may be insufficient to the level of need experienced by a person.15 Another explanation is that grievers might benefit from assistance with harnessing their natural support networks. One study of bereaved family carers showed that a key theme related to utilising social networks (eg, seeking and accepting support, expressing support needs).22

Limitations

While the same questions were asked in both surveys, we acknowledge the different recruitment methodologies in the two studies led to the different age distribution of the bereaved and their relationship to the deceased. Nevertheless, the findings were remarkably similar.

The limitations of drawing on data from the anonymous Australian survey are related to the study sample which is not a random sample of the general bereaved population. However its demographic composition compares well with a large mortality follow back survey in the United Kingdom, and these limitations have been highlighted in previous publications related to the survey.1,21 In general, similar postal surveys, with no reminder follow-up have similar response rates. Those who did not respond to the survey may have had different experiences to those reported in this study. Having selected respondents from funeral providers’ databases could have influenced the considerable number who felt supported by these providers in the Australian study.

The survey items in the Irish study were included in a wider survey omnibus. The company uses quota controls to ensure a nationally representative sample. However, the survey is limited to those who own a telephone.

Conclusion

Bereavement care varies across settings and locations in both Australia and Ireland. A public health approach to bereavement care is needed to support ‘everyday assets’ in the community who care for the majority of the bereaved, without the over-reach from professional services.40 As highlighted in Aoun and colleagues,21 the compassionate communities approach, so far focused on care of the dying, is well and truly operational in the bereavement phase, but needs to be strengthened by identifying a range of useful practice models.

A first step in this process should be to develop standards for bereavement care in the two countries which would provide a framework for services, providing guidance on level of service provision, associated staff competencies, and training needs. Although this research has shown more similarities than differences between the two countries, developing comprehensive guiding standards differed between the two countries. At the Australian policy level, the research has informed the development of Standard 6 on Grief Support in the revised National Palliative Care Standards in Australia.41 In particular, standards stated ‘the service develops strategies and referral pathways in partnership with other providers in the community’ and ‘referrals to mental health specialists and counselling professionals are made when clinically indicated’. However, Ireland went a step further and a recent report ‘Enhancing Adult Bereavement Care across Ireland’ endorsed the ‘Pyramid Model’ (as in Aoun and colleagues)1 as a way forward for a national framework to shape bereavement care policy, planning and service delivery.18 This framework was developed through a national collaborative process, involving both state and voluntary organisations, at all levels of service provision. It is the first step in a process to enhance bereavement care provision across Ireland and will be used as a guide in further developments such as, national standards and mapping of service provision across Ireland.42 Ireland has a reputation for ‘doing death well’, partly as a result of the elaborate, traditional rituals or wakes at the time of death. Such public affirmations of dying, death, and grief, are key to the compassionate communities approach.43

Acknowledgments

The research team acknowledges the contribution of bereaved people to the surveys in both countries, and the cooperation of funeral providers in Australia. We would also like to acknowledge the support of Dr Barbara Coughlan, School of Nursing, Midwifery and Health Systems, University College Dublin, the contribution of John Weafer from Weafer Research Associates, and Denise Howting for assisting with the analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Samar M. Aoun  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4073-4805

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4073-4805

Lauren J. Breen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0463-0363

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0463-0363

Contributor Information

Samar M. Aoun, Public Health Palliative Care Unit, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, VIC 3086, Australia; Perron Institute for Neurological and Translational Science, Perth, WA, Australia.

Orla Keegan, Irish Hospice Foundation, Dublin, Ireland; Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin, Ireland.

Amanda Roberts, Irish Hospice Foundation, Dublin, Ireland.

Lauren J. Breen, School of Psychology, Curtin University, Perth, WA, Australia

References

- 1. Aoun SM, Breen LJ, Howting DA, et al. Who needs bereavement support? A population based survey of bereavement risk and support need. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0121101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kersting A, Brähler E, Glaesmer H, et al. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. J Affect Disord 2011; 131: 339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, et al. Prolonged grief disorder: psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guldin M-B, Jensen AB, Zachariae R, et al. Healthcare utilization of bereaved relatives of patients who died from cancer. A national population-based study: healthcare utilization of bereaved relatives of cancer patients. Psychooncology 2013; 22: 1152–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stephen AI, Macduff C, Petrie DJ, et al. The economic cost of bereavement in Scotland. Death Stud 2015; 39: 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet 2007; 370: 1960–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rumbold B, Aoun S. Bereavement and palliative care: a public health perspective. Prog Palliat Care 2014; 22: 131–135. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breen LJ, Aoun SM, O’Connor M, et al. Effect of caregiving at end of life on grief, quality of life and general health: a prospective, longitudinal, comparative study. Palliat Med 2020; 34: 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nielsen MK, Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, et al. Do we need to change our understanding of anticipatory grief in caregivers? A systematic review of caregiver studies during end-of-life caregiving and bereavement. Clin Psychol Rev 2016; 44: 75–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nielsen MK, Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, et al. predictors of complicated grief and depression in bereaved caregivers: a nationwide prospective cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 53: 540–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomas K, Hudson P, Trauer T, et al. Risk factors for developing prolonged grief during bereavement in family carers of cancer patients in palliative care: a longitudinal study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 47: 531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burke LA, Neimeyer RA. Prospective risk factors for complicated grief: a review of the empirical literature. In: Stroebe MS, Schut H, van den Bout J. (eds) Complicated grief: scientific foundations for health care professionals. London: Routledge and Taylor & Francis, 2013, pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, et al. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud 2010; 34: 673–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Logan EL, Thornton JA, Breen LJ. What determines supportive behaviors following bereavement? A systematic review and call to action. Death Stud 2018; 42: 104–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu W-M, Forbat L, Anderson K. Correction: death of a close friend: short and long-term impacts on physical, psychological and social well-being. PLoS ONE 2019; 14: e0218026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aoun SM, Breen LJ, Rumbold B, et al. Reported experiences of bereavement support in Western Australia: a pilot study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2014; 38: 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Breen LJ, Aoun SM, O’Connor M, et al. Bridging the gaps in palliative care bereavement support: an international perspective. Death Stud 2014; 38: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mc Loughlin K. Enhancing adult bereavement care across Ireland: a study. Report, The Irish Hospice Foundation, Dublin, June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zisook S, Iglewicz A, Avanzino J, et al. Bereavement: course, consequences, and care. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014; 16: 482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lundorff M, Holmgren H, Zachariae R, et al. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2017; 212: 138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aoun SM, Breen LJ, White I, et al. What sources of bereavement support are perceived helpful by bereaved people and why? Empirical evidence for the compassionate communities approach. Palliat Med 2018; 32: 1378–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Breen LJ, Aoun SM, Rumbold B, et al. Building community capacity in bereavement support: lessons learnt from bereaved caregivers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017; 34: 275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Breen LJ, O’Connor M. Family and social networks after bereavement: experiences of support, change and isolation. J Fam Therap 2011; 33: 98–120. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aoun SM, Rumbold B, Howting D, et al. Bereavement support for family caregivers: the gap between guidelines and practice in palliative care. PLoS ONE 2017; 12: e0184750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dodd A, Guerin S, Delaney S, et al. Complicated grief: knowledge, attitudes, skills and training of mental health professionals: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2017; 100: 1447–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Breen LJ. Professionals’ experiences of grief counselling: implications for bridging the gap between research and practice. Omega 2010; 62: 285–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Breen LJ, Fernandez M, O’Connor M, et al. The preparation of graduate health professionals for working with bereaved clients: an Australian perspective. Omega 2012; 66: 313–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Waller A, Turon H, Mansfield E, et al. Assisting the bereaved: a systematic review of the evidence for grief counselling. Palliat Med 2016; 30: 132–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wittouck C, Van Autreve S, De Jaegere E, et al. The prevention and treatment of complicated grief: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31: 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kirby E, Kenny K, Broom A, et al. The meaning and experience of bereavement support: a qualitative interview study of bereaved family caregivers. Palliat Support Care 2018; 16: 396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aoun SM, Lowe J, Christian KM, et al. Is there a role for the funeral service provider in bereavement support within the context of compassionate communities? Death Studies 2018; 43: 619–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Welch C. Marketing death through erotic art. In: Dobscha S. (ed.) Death in a consumer culture. London: Routledge, 2016, pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stroebe M, Schut H, Boerner K. Cautioning health-care professionals: bereaved persons are misguided through the stages of grief. Omega (Westport) 2017; 75: 455–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harris DL, Bordere TC. Looking broadly at loss and grief: a critical stance. In: Harris DL, Bordere TC. (eds) Handbook of social justice in loss and grief: exploring diversity, equity, and inclusion (Series in death, dying, and bereavement). London: Routledge and Taylor & Francis, 2016, pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Breen LJ, Kawashima D, Joy K, et al. Grief literacy: a call to action for compassionate communities. Death Studies. Epub ahead of print 19 March 2020. DOI: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1739780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hilbers J, Rankin-Smith H, Horsfall D, et al. ‘We are all in this together’: building capacity for a community-centred approach to caring, dying and grieving in Australia. Eur J Person Cent Healthc 2018; 6: 685–692. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aoun SM. Bereavement support: from the poor cousin of palliative care to a core asset of compassionate communities. Prog Palliat Care 2020; 28: 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Doka KJ. Disenfranchised grief in historical and cultural perspective. In: Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, et al. (eds) Handbook of bereavement research and practice: advances in theory and intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2008, pp. 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Robson P, Walter T. Hierarchies of loss: a critique of disenfranchised grief. Omega 2013; 66: 97–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rumbold B, Aoun S. An assets-based approach to bereavement care. Bereave Care 2015; 34: 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Palliative Care Australia. National palliative care standards. Griffith, ACT, Australia: Palliative Care Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42. The Irish Hospice Foundation. Adult bereavement care pyramid. A national framework. Dublin: The Irish Hospice Foundation, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rumbold B, Lowe J, Aoun SM. The evolving landscape: funerals, cemeteries, memorialization, and bereavement support. Omega. Epub ahead of print 18 February 2020. DOI: 10.1177/0030222820904877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]