Abstract

The precise modulation of regional cerebral blood flow during neural activation is important for matching local energetic demand and supply and clearing brain metabolites. Here we discuss advances facilitated by high-resolution optical in vivo imaging techniques that for the flrst time have provided direct visualization of capillary blood flow and its modulation by neural activity. We focus primarily on studies of microvascular flow, mural cell control of vessel diameter, and oxygen level-dependent changes in red blood cell deformability. We also suggest methodological standards for best practices when studying microvascular perfusion, partly motivated by recent controversies about the precise location within the microvascular tree where neurovascular coupling is initiated, and the role of mural cells in the control of vasomotility.

Towards Physiological Understanding of Cerebral Capillary Flow

Neural function is associated with large energetic demands; yet the degree of neural activity across the brain is constantly fluctuating. As a result, a specialized system has evolved to ensure coupling between regional energetic demand and supply through precise spatial and temporal modulation of blood flow (neurovascular coupling) [1]. Three decades of work have shown that within ~2–3 seconds of sensory stimulation, arterioles supplying sensory cortex dilate to increase local perfusion. It is generally accepted that local neuronal activation leads to release of vasoactive substances, which include neurotransmitters and/or physiologically active metabolites such as NO, PGE2, adenosine, and K+ ions [2]. Capillary perfusion is traditionally regarded as passive, such that red blood cell (RBC) velocity increases because of upstream vasodilation. However, several publications have recently turned this concept upside down. Two-photon microscopy of the exposed cerebral cortex of mice has revealed that capillary hyperemia occurs seconds prior to arterial dilation, which calls into question the very basic assumption that relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) drives the initial events leading to functional hyperemia. This conceptual revision raises several novel and exciting questions. Among them, what in fact controls capillary flow? And how is capillary hyperemia transmitted to upstream arterioles? This review will discuss these recent developments and address a current controversy regarding the role of pericytes in capillary hyperemia. We also suggest methodological standards in the study of capillary perfusion, emphasizing among other issues the need for analyses conducted in vivo and at high spatiotemporal resolution, given that proper understanding of the entire vascular bed is predicated upon reliable observations of the tiniest vessels of the vascular tree.

Why Is Studying Capillary Blood Flow Important and How Is It Accomplished?

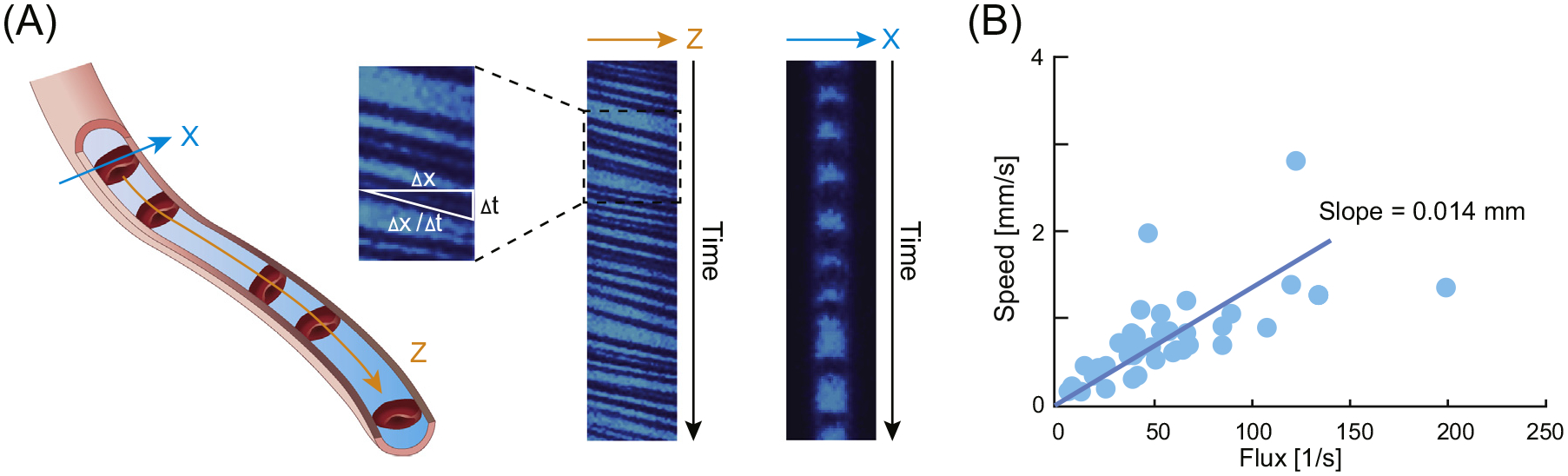

The primary function of the vascular system is to deliver O2 and glucose to metabolically active cells across the capillary bed, while concurrently removing CO2 and other metabolic waste products. Arteries and veins can thus be viewed as structures that support capillary function. Capillary blood flow in vivo is principally studied by two-photon line scan imaging (Figure 1). In this approach, plasma is visualized by an intravascular fluorescent tracer, while the laser continuously scans a single line placed along the principal axis of the capillary [3], demonstrating the flow of RBCs appearing as dark shadows against the plasma fluorescence. The velocity of RBCs along the imaging line is calculated by the rate of their displacement and has been estimated to be in the range of 0.1–1.0 mm/s with an RBC flux of ~40–50/s [3,4]. In a variant of this technique, repetitive scans are acquired by placing the laser line across the capillary lumen. This approach loses information about RBC velocity, but provides accurate measurements of RBC flux, which is linearly correlated with RBC velocity under resting conditions [3]. A major problem in quantifying functional hyperemia is the spontaneous fluctuations in RBC velocities [4]. These fluctuations likely arise due to multiple factors, including vasomotion and transit of leukocytes, which are larger than RBCs. The resultant large variability in baseline RBC velocity calls for measurements of many capillaries to estimate mean functional hyperemia. Interestingly, the variability in capillary flow velocity decreases during hyperemia [5,6], and it has thus been suggested that lesser heterogeneity, in itself, improves brain oxygenation [7].

Figure 1.

Quantification of Capillary Red Blood Cell (RBC) Velocity In Vivo. (A) Two-photon line scanning can be placed either along the length of the capillary (orange arrow Z) or across the capillary (cyan arrow, X). Insert shows two-photon images collected in the Z or X direction. Velocity (x/ t) of RBC passing though the capillary can only be calculated when the line is placed along the length of the capillary. RBC flux can be calculated using both orientations of the line by simply counting the number of RBC passing the capillary per second. (B) RBC flux correlate with RBC velocity (speed). Modified from [3].

Limitations of Brain Slice Preparations in Studying Capillary Flow

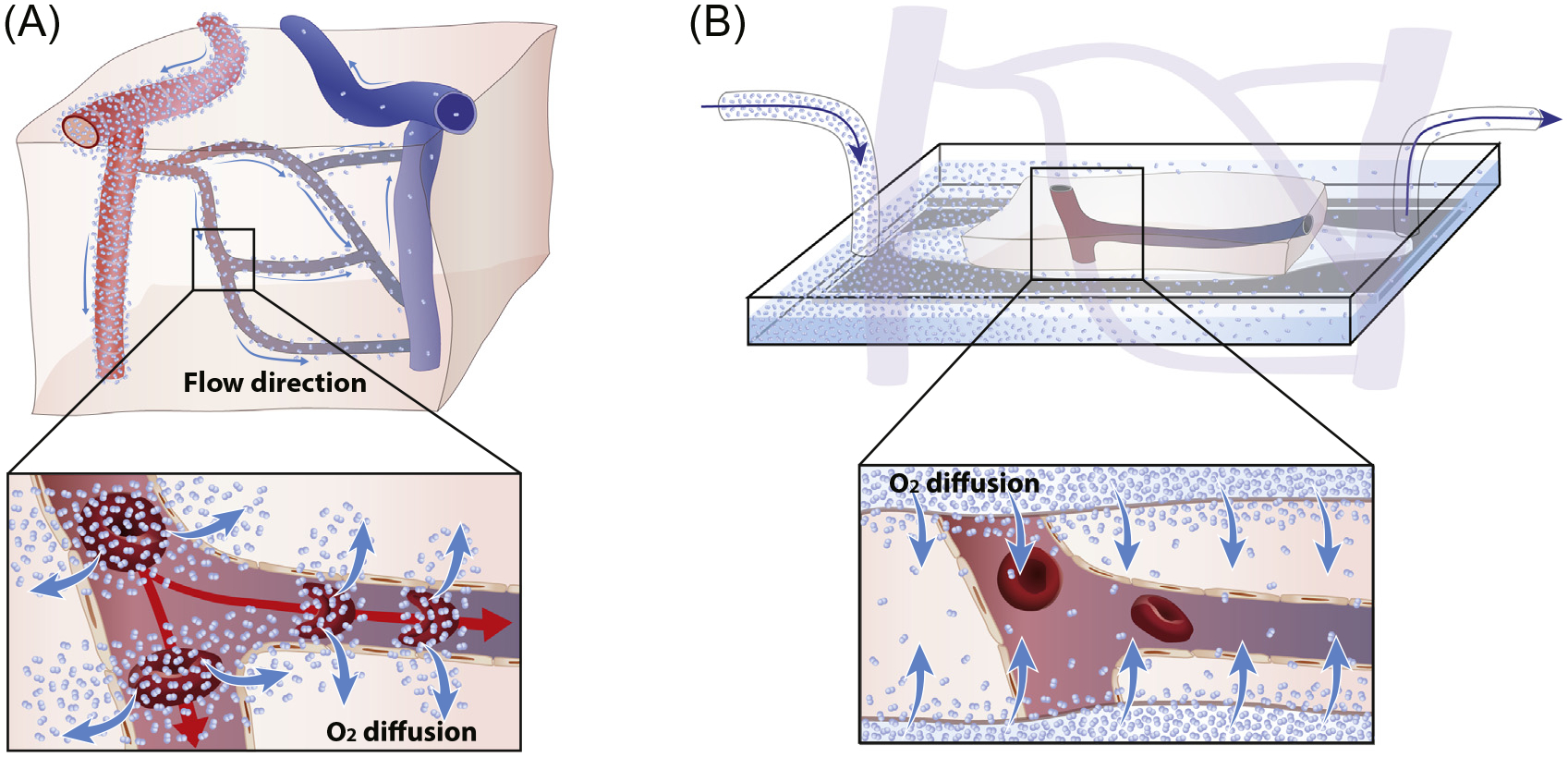

Over the past decade, brain slice preparations have been used to study both arterial and capillary control of vessel diameter and effects of pericytes on vessel dilation or constriction [8–10]. Brain slices have proved useful in the analysis of neurovascular biology and perhaps in identifying candidate signaling molecules. Ultimately, however, the only firm validation of physiologically relevant mechanisms of capillary function is via in vivo analyses. Brain slices suffer from various limitations, some of them inherent to the technique and some specific to the context of studying capillary flow. Prominently, in slices, the main function of the vasculature (delivery of O2 and glucose) has been eliminated. Capillaries in brain slices are no longer connected to arteries and veins and the perfusion pressure is abolished (Figure 2). Instead, the tissue sections are supplied by O2 and glucose from the incubation medium. Moreover, decapitation and cutting of the brain slices releases a multitude of vasoactive compounds that (among other effects) constrict or relax vascular SMCs in an unpredictable and time-dependent manner. The lack of a baseline vascular tone and the resulting need to preconstrict vessels with pharmacological agents during vasomotility studies is another major limitation of slices [11]. The use of electrical stimulation to induce vasomotility likely activates multiple signaling pathways simultaneously. Moreover, the composition of artificial cerebrospinal fluid used for brain slice studies often contains constituents at concentrations that are not physiologic and could thus affect vasomotility. Reactive gliosis with retraction of astrocytic processes and microglial cell activation is observed as early as 1.5 hours after slice cutting [12], even though slices may remain viable for another 4–6 hours. The pathological changes in slices include a dramatic upregulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) expression, which has been implicated in vasoregulation in slices, but not in vivo [8,12]. Altogether, when it comes to studying blood flow regulation, the utility of brain slices is extremely limited. For example, recent publications reporting direct control of capillary and arteriolar flow by pericytes and astrocytes [10,13], based on measurement of changes in vessel diameter in slices, are likely limited by the above-mentioned problems. We argue that any candidate mechanism proposed based on slice studies necessitates in vivo validation for making any substantive statement on its physiological relevance; and even in vivo analyses require careful attention to important methodological considerations and caveats, as discussed in the following sections.

Figure 2.

Diagram Illustrating How O2 Is Delivered to the Tissue In Vivo versus Ex Vivo. (A) Schematic of cortex illustrating the convective polarized passage of red blood cells (RBCs) from arteries to veins driving by the pressure wave during the cardiac cycle. Insert illustrates that O2 is released and passively diffuses into the tissue as RBCs pass the capillaries. (B) When studying vascular regulation in slice preparation, the different segments of the vascular tree are separated and pressure gradients are lost. O2 diffuses passively into the brain slice from the oxygenated bath solution and RBCs no longer serve as a primary source of O2.

Arteriolar Diameter Offers an Indirect Surrogate Measure of Blood Flow In Vivo, but the Underlying Principles Do Not Generalize to Capillaries

Blood flow in arteries and arterioles is generally dictated by Poiseuille’s law, which predicts that the resistance is reduced by the fourth power of increases in the radius of the channel. Arterial blood flow is therefore exquisitely sensitive to minor vessel dilation or constriction. Measurement of arterial diameter has been used for decades as a sensitive surrogate of blood flow. However, as one proceeds to channels of narrower diameter, the effects of viscosity increase, and therefore other principles apply to flow in capillaries compared with arteries and arterioles. The average diameter of mouse RBCs is ~5.5 μm, but despite this small size, they are squeezed through capillaries, the luminal diameter of which is only ~4.2 μm. This passage relies upon the deformability of RBCs, which increases upon deoxygenation [14]. A key component in this mechanism is the band 3 protein anion exchanger 1 (eAE1), a structural element of the erythrocyte cell membrane, occupying about 25% of its surface. When O2 is released into the tissue, ankyrin is displaced from band 3, leading to detachment of the spectrin/actin cytoskeleton from the membrane [15,46]. This weakening of membrane-cytoskeletal interactions accounts for the increasing deformability and higher velocity of deoxygenated RBCs, without changes in the capillary diameter [14].

Several two-photon imaging studies have used capillary diameter as a surrogate for capillary flow in the exposed cerebral cortex of anesthetized mice. This is problematic for several reasons. First, the optical resolution of an optimally aligned two-photon microscope is ~300 nm when imaging at the surface of the brain, but this resolution declines dramatically when focusing on deeper vascular structures due to scattering of the emitted light and markedly reduced excitation [3]. The reported dilations of cortical capillaries ranged from 1% to 3% of the baseline diameter [10,16], corresponding to an increase in diameter of 50 to 150 nm for the typical ~4.5 μm capillary diameter in mice [9,10]. Thus, even under optimal circumstances, and disregarding brain motion associated with vascular pulsatility and breathing, two-photon microscopy is unfit to reliably detect bona fide physiological changes of capillary diameter in vivo. Moreover, as noted above, the high viscosity of RBC passage through capillaries and the increases in RBC deformability upon changes in PO2 and K+ violate Poiseuille’s law.

Pericytes and SMCs Are Distinct Microvascular Mural Cell Types That Require Precise Identification during Vasomotility Studies

An essential step in investigating the mechanisms controlling capillary blood flow is clarifying which mural cells that surround microvessels are the ones that can exert contractile forces and relax during neural activation. To properly study the unique physiological properties of mural cells (contractility, electrophysiology, and signaling), it is essential to use specific morphological and molecular markers to distinguish between the different mural cell types. Particular controversy has surrounded the definition of pericytes versus SMCs. Some studies have relied on classical morphological criteria such as vessel diameter and branch order, ‘bump-on-a-log’ morphology of pericytes [9,10,17], as well as markers such as NG2 [17] and PDGFRβ [16]. However, none of these markers are specific for either of these cell types, and branch order and diameter are unreliable features for their unambiguous identification [18–20]. Importantly, many functional studies have been performed in slice preparations, where it is difficult (in addition to various caveats listed earlier) to preserve and examine the 3D vascular architecture. Consequently, it is challenging in slices to delineate the precise boundaries between pericytes and SMCs along the vascular tree. This has contributed to confusion in the field with regards to the definitions of mural cells [21] and their specific functions during neurovascular coupling and in neuropathological processes.

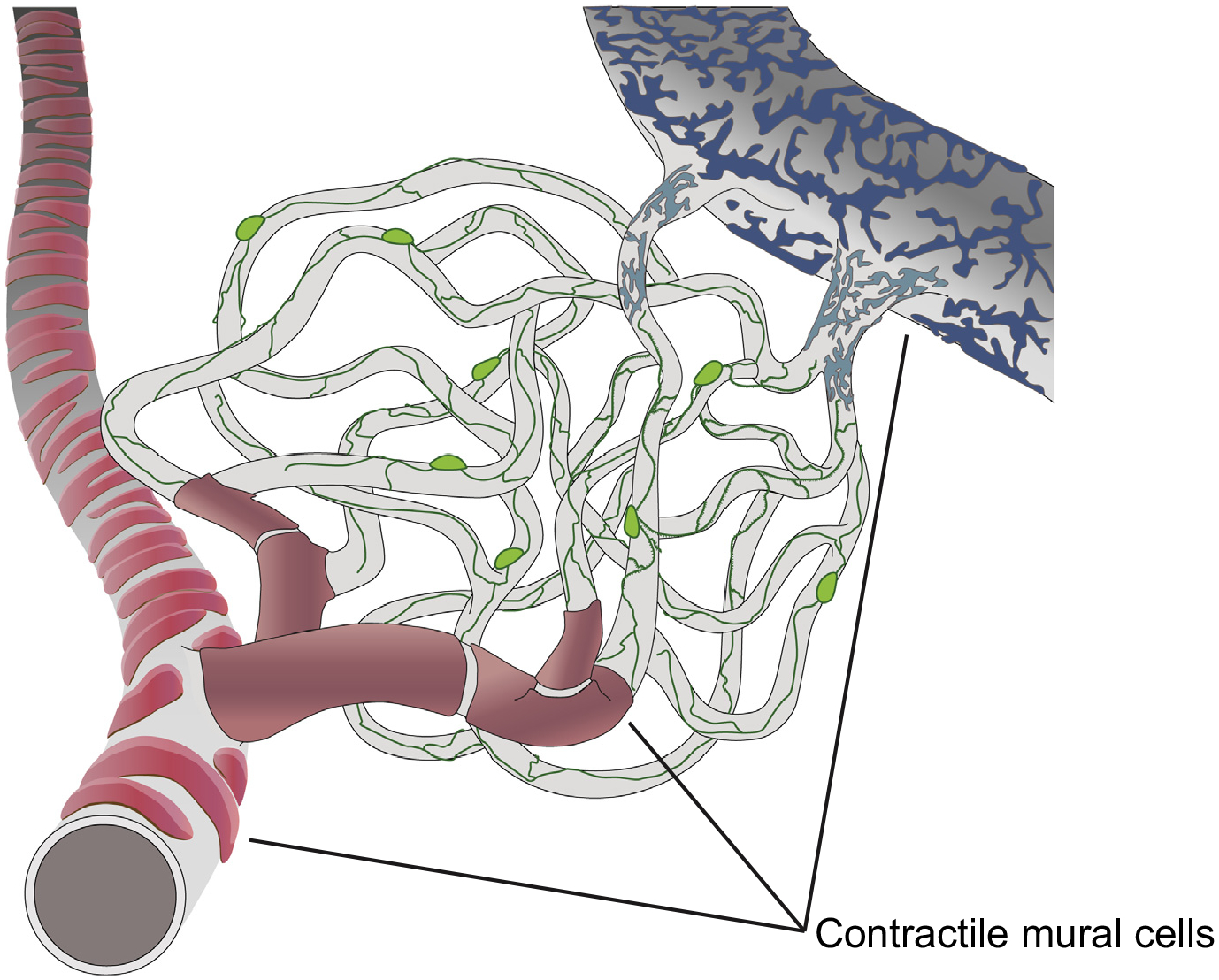

To advance the understanding of mural cells and their functions, a number of recent studies from our groups and others have applied various novel tools, including high-resolution intravital optical imaging [14,18,22,23], pericyte-specific dyes [19], functional interrogation with direct optogenetic stimulation [18], calcium imaging [18,24], and single cell transcriptome analysis [20,25,26]. These methodologically diverse studies have provided a remarkably consistent picture. The analyses show that brain pericytes are a distinct and (in our interpretation) homogeneous mural cell type, are characterized by longitudinal processes that span multiple vessels, surround about 85% of intraparenchymal microvasculature, and do not express the contractile protein smooth muscle actin (αSMA) (Figure 3). In contrast, immediately adjacent precapillary and arteriolar SMCs are ring-like cells that surround about 15% of brain microvessels, robustly express αSMA, and have a transcriptome that can be clearly segregated from that of pericytes [20,25,26]. Terminal precapillary SMCs may differ slightly from arteriolar SMCs by displaying a more elongated ring-like morphology and lower levels of αSMA expression [18,20,27,28], although they do not appear to have additional significant transcriptome differences [20,28]. Consistent with the ring-like morphology of SMCs, which is optimal for exerting radial forces, and with their αSMA expression, it was shown that only arteriolar and precapillary SMCs, but not capillary pericytes, were contractile and able to modulate vasomotility following sensory stimulation or direct mural cell optogenetic activation in the live mouse cortex [18] and olfactory bulb [24] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Distinct Mural Cell Types with and without Contractile Capacity along the Microvascular Tree. Pericytes (green) are distinct mural cells with long filamentous processes that can span multiple capillary segments and spiral ~85% of the intraparenchymal microvascular length. These cells do not express the contractile protein αSMA and do not contract or relax upon sensory stimulation or direct in vivo optogenetic activation. In contrast, smooth muscle cells (red) have a ring-like morphology, ideal for exerting radial forces, robustly express αSMA, and readily constrict upon optogenetic stimulation. Mural cells around venules (blue) have a distinct patchwork morphology, express low levels of αSMA, and may have weak contractile capacity.

Precise identification of mural cell types is also important in the context of neuropathological processes [29]. For example, after recanalization of large vessels following stroke, capillaries frequently remain occluded, preventing adequate tissue reperfusion. The mechanisms causing such ‘no-reflow’ phenomenon are complex [30,31], and advancing their understating may aid in the design of therapies to diminish ischemic injury. Previous studies in brain slices have claimed that during ischemia, capillary pericytes die ‘in rigor’, causing microvascular spasm and occlusion [10,17]. In contrast, high-resolution intravital imaging during ischemia and in experimental spreading depolarization has demonstrated that viable SMCs in precapillary arterioles, but not capillary pericytes, undergo transient hypercontractility leading to vasospasm and distal capillary thrombosis [18], consistent with decades of previous research [31–33].

Despite their different properties with regards to contractility, both SMCs and capillary pericytes display intermittent calcium (Ca++) transients. In the case of SMCs, Ca++ transients are strongly anticorrelated and synchronous with changes in vessel diameter [18,24], consistent with a role of Ca++ signaling in smooth muscle contractility. Pericytes, by contrast, have higher frequency Ca++ transients that do not correlate well with changes in vasomotility [18,24], although they correlate better with patterns of neuronal activation [24]. This raises the intriguing possibility that pericyte Ca++ transients may participate in intercellular signaling mechanisms, rather than contractile functions. Pericytes may act as homeostatic sensors (i.e., sensors of oxygen, CO2 or glucose) or may respond to activity-dependent local release of neurotransmitters or K+ ions. Signals may then propagate through gap junction channels to more proximal SMCs or via endothelial cells [34] to regulate vasomotility in upstream microvasculature, thereby modulating the retrograde propagation of the hemodynamic response during neural activity [35].

Recommendations for Best Practice in Studying Capillary Hyperemia

Although the study of capillary blood flow regulation is still in its infancy, considerable controversies have already surfaced. We argue that it is indispensable for future studies to agree upon what constitutes ‘best practices’, and what technical pitfalls are best avoided. We venture to list below our recommendations for optimal study design.

Brain State and Anesthesia

We recommend that experiments be conducted in awake or lightly sedated animals, preferably supplied with chronic and not acute cranial windows. To avoid variability associated with diurnal cycles, experiments should be performed at the same time of day, ideally in awake mice acclimated to a reversed light cycle. If anesthesia is used, we encourage reporting this in the paper’s abstract. Measurements of blood gasses should be a requirement in deeply anesthetized animals and can be advantageous in other circumstances as well.

Local Hyperemia versus Global Startle Responses

One important limitation of two-photon analyses of capillary flow is that measurements cannot distinguish local events from global changes. Many physiological stimulation paradigms (such as painful sensory stimuli) are linked to activation of the locus coeruleus [36], which innervates the entire neuraxis with vasoactive noradrenaline. Global release of noradrenaline is generally associated with increases in blood pressure and redistribution of cerebral blood volume. Consequently, a global change in cerebral blood volume could be misidentified as local regulation of blood flow. Therefore, continuous arterial blood pressure monitoring is recommended. Likewise, measurement of arterial blood gases is important given their profound influence on cerebral blood flow. This is particularly relevant in the context of experiments involving painful stimuli or startle in awake animals, due to the induction of hyperventilation in these circumstances.

Spontaneous Fluctuations in Capillary RBC Velocity

To accommodate the large variability in baseline RBC velocity and flux, power analysis indicates that at least 40 capillaries from each of six animals should be included in the analysis [3,37]. Furthermore, changes in capillary diameter/flow could also be passive, resulting from upstream hemodynamic events such as modest changes in systemic blood pressure. Thus, measurements of capillary diameter cannot properly serve as a proxy for RBC velocity.

Identification of Pericytes and SMCs

As mentioned, the identification of pericytes and SMCs has been one of the issues at the core of ongoing controversies regarding the roles of these cell types in neurovascular coupling. Transgenic mice that express a fluorescent protein under the αSMA promoter have opened up opportunities for precise cellular identification of pericytes and for distinguishing them from adjacent precapillary SMCs and postcapillary venule mural cells. Arterioles and precapillary SMCs express αSMA, a protein that is absent from capillary pericytes and is expressed in very low levels in larger venular mural cells [18,20,25,26]. These mice can be crossbred with mice expressing a different fluorophore in all mural cells driven by the PDGFRβ promoter [18]. An alternative for specific identification of pericytes during in vivo imaging is to use the small fluorescent molecule Neurotrace 555, that was recently shown to rapidly and specifically label pericytes after topical application to the exposed cortex [19]. Recently, single cell transcriptome studies have identified genes that are unique to pericytes and absent from SMCs, such as Abcc9 and Kcnj8 [20]. In the near future, transgenic mouse lines using these or other promoters are likely to become available for visualization, manipulation, and accurate identification of mural cells.

What Have ‘Best Practice’ Analyses of Capillary Flow Shown So Far?

The Kleinfeld and Charpak groups pioneered the use of high resolution in vivo line scanning two-photon imaging of the microvasculature as a proxy for RBC velocity [3,37]. It is now solidly documented that capillary RBC velocity exhibits baseline fluctuations extending over an order of magnitude and that RBC velocity and flux correlate under baseline conditions [3,37]. Existing data suggest that capillaries, which are embedded in the O2-consuming neuropil and are exposed to activity-induced changes in extracellular potassium, are immediately responsible for the increased need for energy substrates [10,14], preceding responses on the arterial side by several seconds in cortex. Importantly, regional differences in timing of neurovascular coupling exist. For example, dilation of upstream arterioles typically occurs with a delay of 2–3 s in cortex [10,14], but as early as 600–700 ms after exposure to odors in olfactory cortex [24]. In fact, the fast arteriole dilation in olfactory glomeruli occurs essentially simultaneously with the increase in capillary RBC velocity [24], whereas capillary RBC velocity rises ~1 s after hind limb or whisker stimulation in sensory cortex, or 1–2 s prior to dilation of upstream arterioles [10,14]. It remains to be determined what underlies the regional difference in timing of neurovascular coupling, and that anesthesia plays a role cannot be excluded. Awake animal imaging was used in the olfactory bulb studies [24], whereas the studies in cortex employed alpha-chloralose and light isoflurane [10,14]. Of note, the retina in live animals presents an excellent target organ for hyperemia studies [38,39]. It would be interesting to see how properties of neurovascular coupling in the retina compare to brain regions.

With regard to the vascular mural cells that exert contractile forces leading to vasomotility, it has become clear that for their proper investigation it is inadequate to perform experiments in slice preparation and to measure subresolution changes in vessel diameter as a proxy for flow [10]. It is thus essential to collect experimental data in vivo and use precise mural cell molecular markers, as capillary pericytes and adjacent precapillary SMCs are distinct cell types with different functions. Thanks to the ability to sparsely label mural cells in transgenic mice using the αSMA promoter [18] and pericyte-specific dyes [19], as well as the ability to visualize and manipulate individual mural cells by high-resolution in vivo imaging and single cell optogenetic stimulation, there is broad recognition now that the expression of αSMA separates SMCs from pericytes and that branch order and microvessel diameter are unreliable features to define a mural cell as a pericyte or SMCs. One study that seemed to counter some of these arguments is a 2017 publication that employed measurements of both capillary diameter and RBC velocity in vivo, and demonstrated that capillary hyperemia is suppressed in pericyte-deficient transgenic mice [16]. The authors concluded that it is the lack of pericyte-mediated vasomotion that was responsible for uncoupling of neurovascular responses. We note, however, that it is equally possible that chronic pathological changes of vasculature, including blood-brain barrier deficits in pericyte-deficient mice [40], impair capillary hyperemia through a mechanism that does not involve pericytic control of capillary diameter.

Finally, astrocytes have also been shown to play a role in the regulation of neurovascular coupling [8,41,42]. Recently, in vivo Ca++ imaging with genetically encoded indicators [43] has revealed a variable degree of correlation between vasomotility, changes in blood flow and Ca++ transients in astrocytic cell bodies and fine processes [44]. This pattern suggest that astrocytes likely play a complex modulatory role in neurovascular coupling rather than as direct effectors of vasomotility.

Concluding Remarks

The regulation of functional hyperemia is a highly complex mechanism that results from the coordinated interactions of various cell types. The precise contributions of each one of these cells to the modulation of neurovascular coupling remains to be elucidated (see Outstanding Questions). Methodological advances have offered a wealth of new tools for the study of neurovascular coupling. In vivo high-resolution two-photon imaging, label-free differential scatter and adaptive optics to measure single flowing RBC flux, velocity, and vessel hematocrit [45], combined with novel genetically encoded biosensors of cell physiology, have greatly enhanced the ability to investigate the precise cellular mechanisms of microvascular blood flow control and the consequences of its dysregulation in disease.

Outstanding Questions.

What are the precise cellular mechanisms and signals that initiate functional hyperemia?

How do cells within the neurovascular unit communicate with each other to coordinate neurovascular coupling?

How does functional hyperemia propagate through the microvascular tree?

Do calcium transients in pericytes mediate intercellular communication?

What is the precise function of neurovascular coupling?

How is functional hyperemia altered in cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases?

What are the consequences of abnormal neurovascular coupling?

Furthermore, recent studies using single cell transcriptome analysis have identified genes that are uniquely expressed in various cells of the neurovascular unit, such as capillary pericytes and arteriolar SMCs [20,25,26]. The knowledge derived from such studies will facilitate the development of transgenic mouse lines with precise specificity to the different mural cell types, allowing cell-specific expression of fluorescent proteins and biosensors, as well as single cell molecular manipulations that will allow sophisticated investigation of cellular mechanisms of brain microvascular flow regulation in vivo.

Highlights.

In vivo optical imaging studies in rodents over the past two decades have significantly advanced the understanding of cellular mechanisms of neurovascular coupling.

Rapid changes in red blood cell deformability and blood rheology due to fluctuations in oxygen levels can increase capillary cell flux prior to microvascular dilation.

We review in vivo evidence indicating that activity-dependent changes in regional blood flow are mediated by smooth muscle cell contractility in arterioles but not by pericytes.

Technical recommendations are provided for reproducible studies of neurovascular coupling in vivo and proper functional characterization of pericytes and smooth muscle cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Union (EU) Joint Program, Neurodegenerative Disease Research Program (JPND; Horizon 2020 Framework Programme, grant agreement 643417/DACAPO-AD), Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Network of Excellence (16/CVD/05), and NIH/NINDS NS110049 to M.N. and by NIH NS089734, RF1AG058257, and Cure Alzheimer’s Fund to J.G. We thank Dan Xue for expert graphic design.

References

- 1.Iadecola C (2017) The neurovascular unit coming of age: a journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Neuron 96, 17–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girouard H and Iadecola C (2006) Neurovascular coupling in the normal brain and in hypertension, stroke, and Alzheimer disease. J. Appl. Physiol 100, 328–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinfeld D et al. (1998) Fluctuations and stimulus-induced changes in blood flow observed in individual capillaries in layers 2 through 4 of rat neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 95, 15741–15746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villringer A et al. (1994) Capillary perfusion of the rat brain cortex. An in vivo confocal microscopy study. Circ. Res 75, 55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefanovic B et al. (2008) Functional reactivity of cerebral capillaries. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 28, 961–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulte ML et al. (2003) Cortical electrical stimulation alters erythrocyte perfusion pattern in the cerebral capillary network of the rat. Brain Res. 963, 81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmussen PM et al. (2015) The effects of transit time heterogeneity on brain oxygenation during rest and functional activation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 35, 432–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zonta M et al. (2003) Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat. Neurosci 6, 43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peppiatt CM et al. (2006) Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes. Nature 443, 700–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall CN et al. (2014) Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease. Nature 508, 55–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iadecola C and Nedergaard M (2007) Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat. Neurosci 10, 1369–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takano T et al. (2014) Rapid manifestation of reactive astrogliosis in acute hippocampal brain slices. Glia 62, 78–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mishra A et al. (2016) Astrocytes mediate neurovascular signaling to capillary pericytes but not to arterioles. Nat. Neurosci 19, 1619–1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei HS et al. (2016) Erythrocytes are oxygen-sensing regulators of the cerebral microcirculation. Neuron 91, 851–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stefanovic M et al. (2013) Oxygen regulates the band 3-ankyrin bridge in the human erythrocyte membrane. Biochem. J 449, 143–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kisler K et al. (2017) Pericyte degeneration leads to neurovascular uncoupling and limits oxygen supply to brain. Nat. Neurosci 20, 406–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yemisci M et al. (2009) Pericyte contraction induced by oxidative-nitrative stress impairs capillary reflow despite successful opening of an occluded cerebral artery. Nat. Med 15, 1031–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill RA et al. (2015) Regional blood flow in the normal and ischemic brain is controlled by arteriolar smooth muscle cell contractility and not by capillary pericytes. Neuron 87, 95–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damisah EC et al. (2017) A fluoro-Nissl dye identifies pericytes as distinct vascular mural cells during in vivo brain imaging. Nat. Neurosci 20, 1023–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanlandewijck M et al. (2018) A molecular atlas of cell types and zonation in the brain vasculature. Nature 554, 475–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Attwell D et al. (2016) What is a pericyte? J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 36, 451–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernández-Klett F et al. (2010) Pericytes in capillaries are contractile in vivo, but arterioles mediate functional hyperemia in the mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 22290–22295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berthiaume A-A et al. (2018) Dynamic remodeling of pericytes in vivo maintains capillary coverage in the adult mouse brain. Cell Rep. 22, 8–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rungta RL et al. (2018) Vascular compartmentalization of functional hyperemia from the synapse to the pia. Neuron 99, 362–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chasseigneaux S et al. (2018) Isolation and differential transcriptome of vascular smooth muscle cells and mid-capillary pericytes from the rat brain. Sci. Rep 8, 12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saunders A et al. (2018) Molecular diversity and specializations among the cells of the adult mouse brain. Cell 174, 1015–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant RI et al. (2019) Organizational hierarchy and structural diversity of microvascular pericytes in adult mouse cortex. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 39, 411–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He L et al. (2018) Single-cell RNA sequencing of mouse brain and lung vascular and vessel-associated cell types. Sci. Data 5, 180160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu X et al. (2017) Cerebral vascular disease and neurovascular injury in ischemic stroke. Circ. Res 120, 449–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grutzendler J et al. (2014) Angiophagy prevents early embolus washout but recanalizes microvessels through embolus extravasation. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 226ra31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ames A et al. (1968) Cerebral ischemia. II. The no-reflow phenomenon. Am. J. Pathol 52, 437–453 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mchedlishvili GI et al. (1967) Reaction of different parts of the cerebral vascular system in asphyxia. Exp. Neurol 18, 239–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cipolla MJ et al. (2013) Mechanisms of enhanced basal tone of brain parenchymal arterioles during early postischemic reperfusion: role of ET-1-induced peroxynitrite generation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 33, 1486–1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Longden TA et al. (2017) Capillary K+-sensing initiates retrograde hyperpolarization to increase local cerebral blood flow. Nat. Neurosci 20, 717–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iadecola C et al. (1997) Local and propagated vascular responses evoked by focal synaptic activity in cerebellar cortex. J. Neurophysiol 78, 651–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bekar LK et al. (2012) The locus coeruleus-norepinephrine network optimizes coupling of cerebral blood volume with oxygen demand. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 32, 2135–2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaigneau E et al. (2003) Two-photon imaging of capillary blood flow in olfactory bulb glomeruli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 100, 13081–13086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornfield TE and Newman EA (2014) Regulation of blood flow in the retinal trilaminar vascular network. J. Neurosci 34, 11504–11513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biesecker KR et al. (2016) Glial cell calcium signaling mediates capillary regulation of blood flow in the retina. J. Neurosci 36, 9435–9445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell RD et al. (2010) Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 68, 409–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takano T et al. (2006) Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat. Neurosci 9, 260–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mulligan SJ and MacVicar BA (2004) Calcium transients in astrocyte endfeet cause cerebrovascular constrictions. Nature 431, 195–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y et al. (2011) An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. Science 333, 1888–1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gu X et al. (2018) Synchronized astrocytic Ca2+ responses in neurovascular coupling during somatosensory stimulation and for the resting state. Cell Rep. 23, 3878–3890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guevara-Torres A et al. (2016) Label free measurement of retinal blood cell flux, velocity, hematocrit and capillary width in the living mouse eye. Biomed. Opt. Express 7, 4228–4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou S et al. (2019) Oxygen tension-mediated erythrocyte membrane interactions regulate cerebral capillary hyperemia. Sci. Adv 5, eaaw4466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]