Introduction

Rectal cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the United States, with an overall incidence of 11.7 cancers per 100,000 persons for all ages and 44 cancers per 100,000 persons for those over 65 years [1]. There has been a rapid increase in the incidence of rectal cancer in younger patients, as those born in 1990 have four times the risk of developing rectal cancer compared to those born in 1950 [2]. By far, adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic type of rectal cancer. MRI is the established imaging modality for local staging of rectal adenocarcinoma and has important implications for patient management and outcomes [3,4].

In addition to adenocarcinoma, there are a variety of less common rectal neoplasms and non-neoplastic mimics. The practicing abdominal radiologist should be familiar with the imaging features of these rare rectal masses, as the management and prognosis of these masses can be significantly different compared to that of rectal adenocarcinoma.

The aim of this article is to review some of the rare rectal tumors beyond adenocarcinoma, with a particular emphasis on the MRI imaging features, local staging, standard treatment, and prognostic implications.

Intramural malignant tumors

Rectal Lymphoma

Extra-nodal lymphoma arises most commonly in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GI tract lymphomas are most commonly non-Hodgkin’s, B-cell lymphomas [5,6]. On the other hand, primary colorectal lymphoma is rare and accounts for only 0.1%–0.4% of primary rectal neoplasms and only a small proportion of GI tract lymphomas. Colorectal lymphoma has a male predominance (a 2:1 male to female ratio) and is most often seen in the sixth or seventh decade of life [7,8]. The risk is increased for patients with inflammatory bowel disease or immunosuppression [7]. Bleeding is an uncommon symptom at presentation (~20% of cases); abdominal pain and constitutional symptoms are more common [8,9].

When the rectum is involved, it is usually in the context of widespread systemic disease and there is adenopathy outside the GI tract. In contrast, primary gastrointestinal lymphoma will be present without systemic disease. Rectal lymphoma tends to involve multiple segments and longer segments of colon; however, obstruction and perforation from the tumor is uncommon [10].

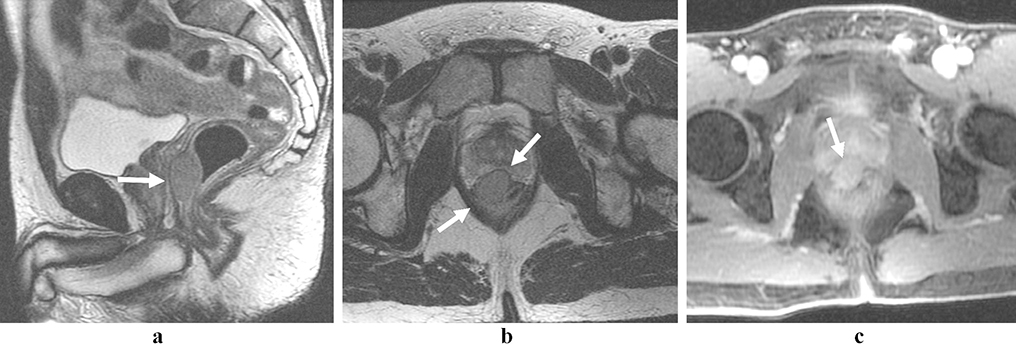

Rectal lymphoma can be protean in its appearance and can be polypoid, circumferential, ulcerated or may simply be seen as mucosal nodularity, and its appearance can overlap with rectal adenocarcinoma [7]. On MRI, high T2 signal and intermediate T1 signal are the norm, and mild to moderate enhancement may be expected [6,7]. Given the high cellularity of lymphoma, restricted diffusion is present [11] (Figure 1).

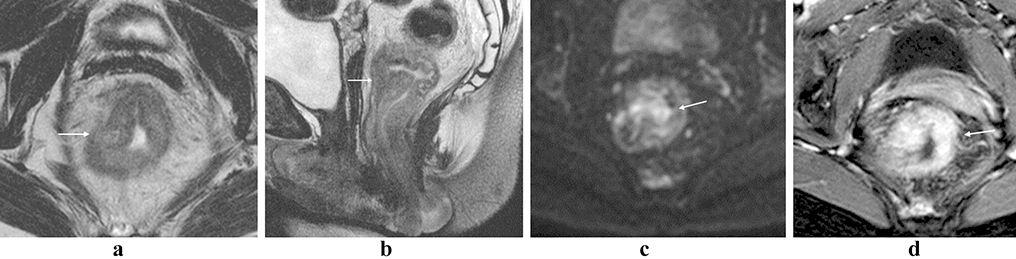

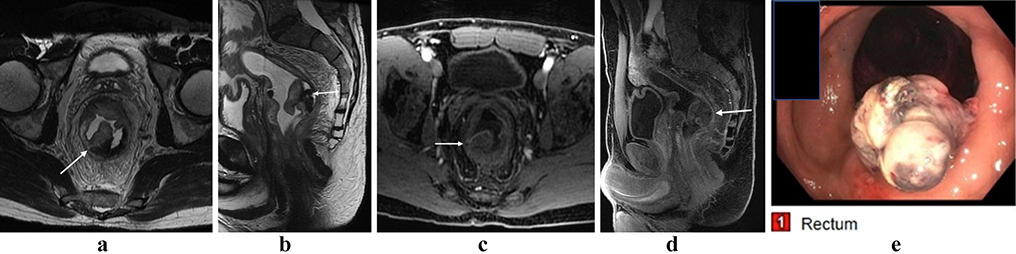

Figure 1:

Rectal lymphoma. Partially circumferential mass in the low rectum with intermediate T2 signal (a, b; arrows). There is restricted diffusion within the lesion (c, arrow), and avid post-contrast enhancement (d, arrow).

Staging of GI tract lymphoma can be done using the Lugano classification system [12] (Table 1).

Table 1.

GI lymphoma classification adopted at the Consensus Conference in Lugano.

| Stage I Tumor confined to gastrointestinal tract, single primary site, and multiple noncontiguous lesions. |

| Stage II Tumor extends into the abdominal cavity from the primary gastrointestinal site. |

| II1 Local nodal involvement |

| II2 Distant nodal involvement |

| Stage III Penetration through serosa to involve adjacent organs or tissues |

| Stage IV Disseminated extranodal involvement or a gastrointestinal tract lesion with supradiaphragmatic nodal involvement |

Neuroendocrine tumors of the rectum

Neuroendocrine tumors (NET) [13] of the GI tract are rare, with fewer than 20,000 cases diagnosed over a 33-year period beginning in 1975. The overall incidence has increased over that time, probably due to improved and more frequent investigation with endoscopic procedures, particularly for NETs arising from the stomach and rectum [13]. Although neuroendocrine cells are found in multiple organ systems, they are relatively high in concentration in the GI tract [14,15]. NETs can become biologically active due to the overproduction of cytokines and/or hormones [14].

The most common locations for NETs arising from the GI tract are the small bowel and rectum. Although small bowel NETs are traditionally thought to be most common [15,16], others have suggested that the incidence of rectal NETs has increased and is now greater than small bowel NETs [17,18]. The reason for this is currently unknown [17] but may relate to the increased detection from the more widespread use of endoscopic imaging than in the past.

Patients with rectal NET are often in their sixth decade of life [17,19,7] and there is no difference in incidence between males and females [7,14]. Rectal NETs are most often diagnosed on screening colonoscopy or incidentally, as they are often asymptomatic [19,14]. When symptomatic, pain with defecation, rectal bleeding and constipation are common [19,20]. Rectal NETs almost never cause the traditional “carcinoid” syndrome.

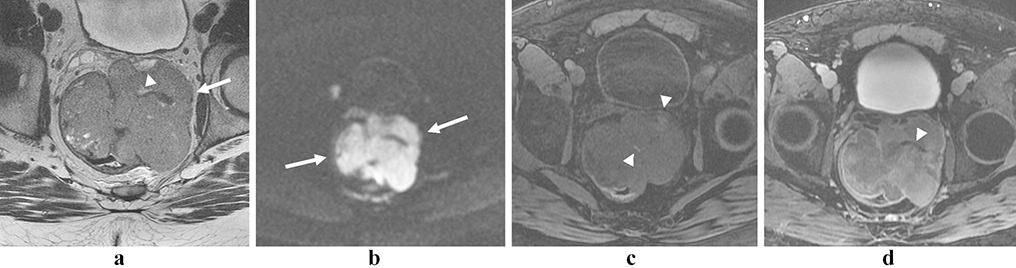

On MRI, rectal NETs often present as a small, solitary submucosal mass or nodule. The majority are 1 cm in diameter or smaller [15], and only a small number (~ 5%) are larger than 2 cm [19]. The most common appearance is a single homogenously enhancing superficial rectal mass that is T1 isointense and T2 iso- to hyperintense [7,21]. The superficial appearance can be attributed to the location of enteroendocrine cells in the muscularis mucosa or the submucosal layer of the bowel wall [22]. Less commonly, more aggressive imaging features that resemble rectal adenocarcinoma are seen, such as transmural extension or an irregular mass, particularly when the NET has a poorly differentiated histology [23] (Figures 2–3).

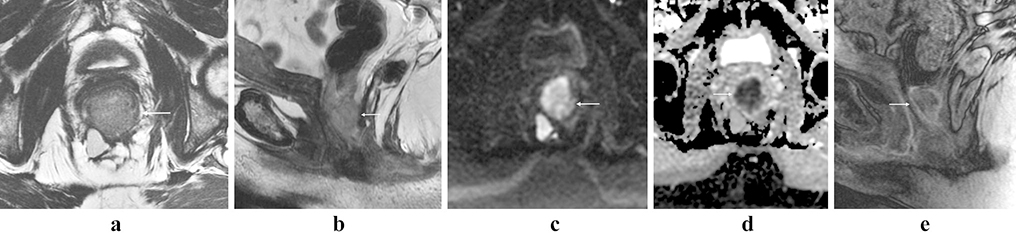

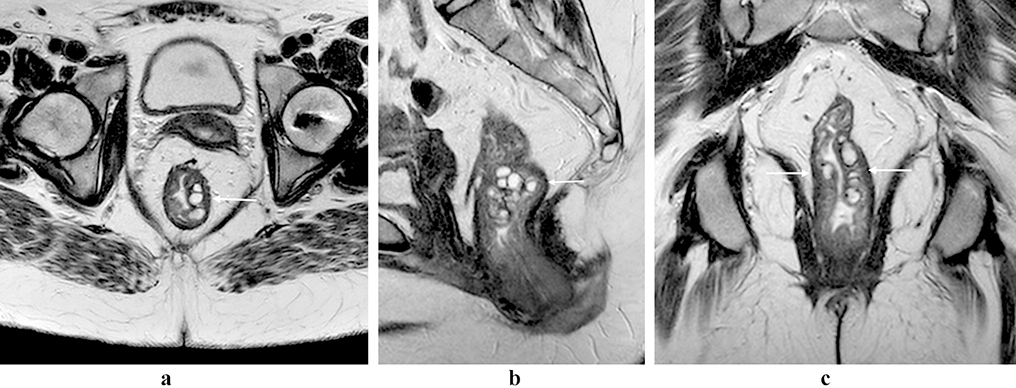

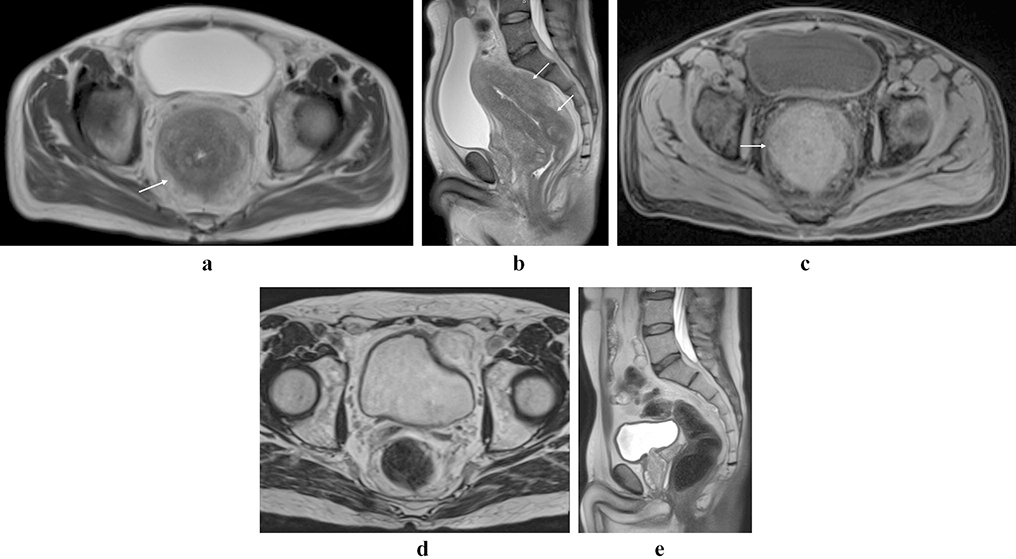

Figure 2:

Rectal neuroendocrine tumor. 60 year old female with a T2 iso- to hyper-intense mass in the low rectum (a and b, arrows), with marked restricted diffusion (c and d, arrows) and enhancement (e, arrow).

Figure 3:

Rectal neuroendocrine tumor. 79 year-old female with an atypical, locally aggressive neuroendocrine tumor. Axial oblique (a) and coronal oblique (b) T2 images show direct extension into the pelvis (arrows). Restricted diffusion (c, arrow) and avid homogenous enhancement (d, arrow), as is more typical of rectal NET.

Because rectal NETs are usually low grade tumors, nodal metastases are uncommon (less than 10%) and distant metastases are even more rare [19]. The size of the primary tumor is important in predicting metastases in rectal NETs; tumors under 1 cm in size rarely metastasize [14]. Larger tumors, especially those larger than 2 cm, and tumors that have invaded beyond the rectal wall are at a higher risk for developing metastatic disease.

NETs are classified by both stage and World Health Organization grade (low/G1, intermediate/G2 or high/G3), based on mitotic count and Ki67 index [24], and both systems have prognostic implications. The 2017 TNM staging classification from the American Joint Cancer Commission (AJCC) for rectal NETs is summarized in Table 2 [25].

Table 2.

AJCC 2017 TNM for rectal NET.

| T Category |

| TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 No evidence of primary tumor |

| T1 Tumor invades the lamina propria or submucosa and is <= 2 cm |

| T1a Tumor < 1 cm in greatest dimension |

| T1b Tumor 1–2 cm in greatest dimension |

| T2 Tumor invades the muscularis propria or is > 2 cm with invasion of the lamina propria or submucosa |

| T3 Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into subserosal tissue without penetration of overlying serosa |

| T4 Tumor invades the visceral peritoneum (serosa) or other organs or adjacent structures |

| N Category |

| NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 No regional lymph node metastasis has occurred |

| N1 Regional lymph node metastasis |

| M Category |

| M0 No distant metastasis |

| M1 Distant metastasis |

| M1a Metastasis confined to liver |

| M1b Metastasis in at least one extrahepatic site (e.g., lung, ovary, nonregional lymph node, peritoneum, bone) |

| M1c Both hepatic and extrahepatic metastases |

Melanoma

Primary anorectal melanoma is aggressive but extremely rare, accounting for fewer than 1% of all melanomas. Although rectal melanoma may originate from the columnar epithelium of the rectum, it is most often an extension of a primary anal neoplasm and hence the term anorectal melanoma is used [7]. It is typically seen in patients in their forties or fifties, but a wide age range has been reported, with some patients presenting younger than 30 years [21,26,27]. There is a female predominance, with a female to male ratio of 2:1 [26,28].

Symptoms of anorectal melanoma are similar to those of other rectal neoplasms; they include rectal bleeding, pain and weight loss [21]. The mass is often near the anus or in the distal rectum and presents as an intraluminal polypoid mass [23,7,21]. It is sometimes discovered incidentally during surgery for hemorrhoids[29].

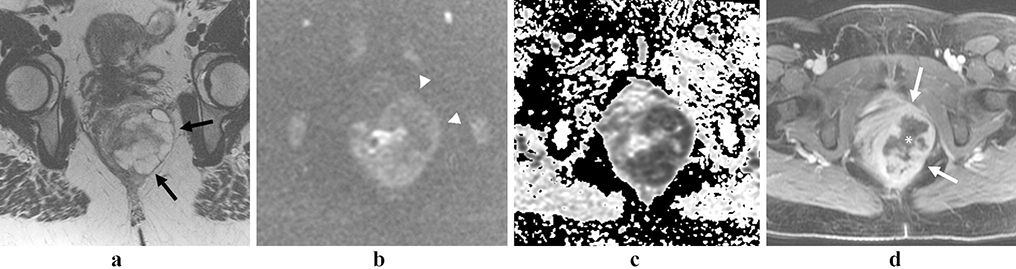

MRI in anorectal melanoma primarily concerns lesion characterization and local staging. A polypoid appearance, sometimes with ulceration, is the norm, while generalized wall thickening and exophytic growth are atypical. Most melanoma cells demonstrate high signal on T1-weighted images due to T1-shortening caused by paramagnetic free radicals within the melanin pigment [23]. The typical appearance is therefore T1 hyperintense, with high or mixed signal intensity on T2-weighted images [23]. Peri-tumoral desmoplasia is less common compared with adenocarcinoma. On endoscopy, the lesion appears darkly pigmented due to the presence of melanin (Figure 4).

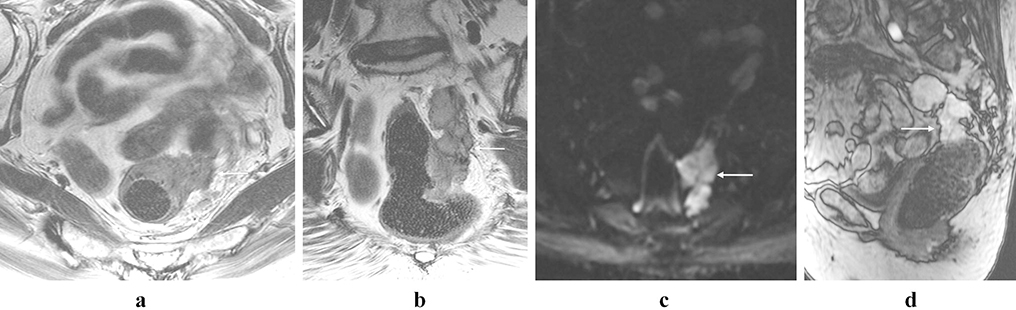

Figure 4:

Anorectal melanoma. Polypoid T2-hyperintense mass at the anorectal junction (a and b, arrows). The mass (arrow) and an adjacent lymph node (arrowhead) show intrinsic T1-shortening on the T1 fat saturated pre-contrast image (c), and the lesion shows heterogeneous enhancement with early perfusion (d, arrow).

A minority of anorectal melanomas (~ 10%–29%) are amelanotic variants. In these cases, the characteristic T1-shortening is not present but the tumors may be T1 hypointense on MRI similar to rectal adenocarcinoma [23,7].

In addition to evaluation of the primary neoplasm, MRI is also useful for evaluation of the locoregional lymph nodes. Similar to the primary tumor, a metastatic lymph node from a T1-hyperintense mass may demonstrate high T1 signal [23]. Lymph node metastases are commonly seen at the initial presentation (60%) [30]. The location of nodal metastases reflects the complex lymphatic drainage of the anorectum. Tumor spread from the lower rectum often goes to mesorectal nodes and subsequently internal iliac nodes. Near the anorectal junction, drainage often goes to the inguinal nodes [31]. The size of primary lesion influences the rate of nodal metastases whereby the latter is more common especially when the primary mass is greater than 3 cm [32]. While the presence of locoregional nodal metastases may be evaluated on MRI, it has not been linked to prognostic outcomes such as recurrence or survival [33].

Distant metastases from anorectal melanoma are identified in up to 40% of patients at diagnosis and often involve the liver, brain or lung [30,33]. The reported fiveyear survival rates are from 10%–15% [7,30].

At present, no pathologic staging system exists that is specific to anorectal melanoma.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), the most common mesenchymal neoplasm of the rectum, can be either malignant or benign; these tumors arise from interstitial cells of Cajal that serve as a pacemaker for bowel peristalsis in the intestinal wall [7,23]. GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the GI tract, but the rectum is the least common location (3%–5%). The stomach and small intestine are much more common sites for GIST, accounting for approximately 60–70% and 20–30% of GIST tumors, respectively [23,7,25]. All GIST tumors have some degree of malignant potential, depending in part on the tumor size and the number of mitoses [23].

GISTs most commonly occur between the fifth and seventh decades of life and are more common in males than in females [34,7]. Approximately one in four GISTs are incidentally diagnosed on imaging; others are found due to symptoms such as bleeding and abdominal pain [35,7,34]. At immunohistochemical evaluation, most GISTs express CD117 [13], allowing them to be differentiated from other mesenchymal neoplasms such as leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma.

A GIST will usually be a well-circumscribed, smooth submucosal mass, but it can occasionally ulcerate [34]. MRI has a distinct role in localizing the lesion and in determining the relationship of the lesion to the surrounding anatomy for surgical planning [34]. An exophytic component is characteristic of GISTs, and presents much more often than adenocarcinoma [7]. Many GISTs have a pseudocapsule that can limit infiltration into adjacent structures which tend to be displaced rather than infiltrated [25]. Invasion of the adjacent organs, bowel obstruction and lymph node metastases are much less common than with adenocarcinoma.

Additionally, smaller GISTs may show homogeneous arterial enhancement, whereas larger tumors have milder, heterogeneous enhancement [35,36]. Large GISTs have some unique features, including a “dumb-bell’ shape. They may have central necrosis and can communicate with the bowel lumen [35,37] (Figures 5–6).

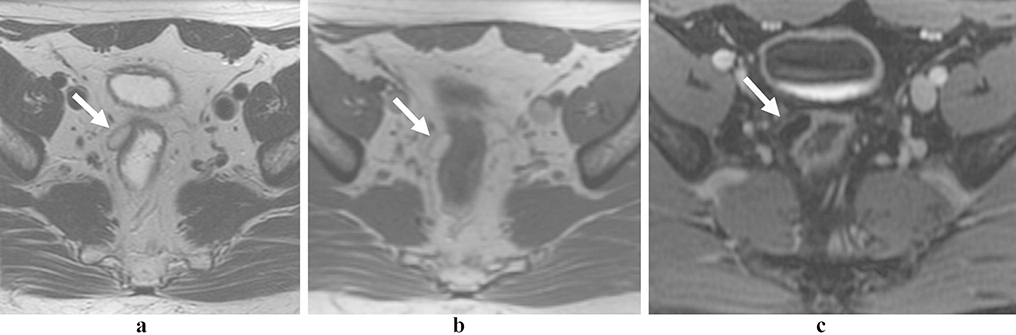

Figure 5:

Rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. 56-year-old male with a round mural mass with well defined tumor margins (arrows; a and b), and the tumor indents the posterior aspect of the prostate gland (b, anterior arrow). There is avid homogeneous enhancement (arrow, c). There is no adenopathy.

Figure 6:

Rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. 46 year-old male with a bulky lobulated mass in rectum with ‘dumbbell-like’ appearance (a, arrow), protruding both into the lumen and growing exophytically. The lesion contact and indents bilateral seminal vesicles (a, arrowhead). There are small internal areas of hemorrhage on the T1 fat saturated pre-contrast image (c, arrowhead), and necrosis or cystic degeneration (d, arrowhead).

Nodal metastases are rare for GISTs, even with large tumors; metastases tend to occur in the liver and peritoneum [25,34]. Other than metastases or the lack of local invasion, no imaging features can reliably differentiate benign from malignant GIST and this distinction must be made through pathology.

TNM staging of GISTs is relatively straightforward. T-staging is determined by only tumor size since the majority of these tumors have a transmural component [25]. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) GIST Consensus Criteria (25) classifies patients as having a very low, low, intermediate or high risk of recurrence. The reason for this classification is that the biologic behavior of a GIST can be hard to predict, as even histologically “benign” tumors can recur or metastasize. The two factors in this determination are the size of the tumor and mitotic rate (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

AJCC 2017 TNM for GISTs.

| T Category |

| TX Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 No evidence of primary tumor |

| T1 Tumor ≤ 2 cm |

| T2 Tumor > 2 cm but not more than 5 cm |

| T3 Tumor > 5 cm but not more than 10 cm |

| T4 Tumor > 10 cm in greatest dimension |

| N Category |

| N0 No regional lymph node metastasis or unknown lymph node status |

| N1 Regional lymph node metastasis |

| M Category |

| M0 No distant metastasis |

| M1 Distant metastasis |

Table 4.

NIH-Fletcher criteria for GIST risk assessment.

| Risk category | Primary tumor size (cm) | Mitotic count (per 50 high-power fields) |

|---|---|---|

| Very low risk | < 2 | < 5 |

| Low risk | 2–5 | < 5 |

| Intermediate risk | < 5 | 6–10 |

| 5–10 | < 5 | |

| High risk | > 5 | > 5 |

| > 10 | Any mitotic rate | |

| Any size | >10 | |

Leiomyosarcoma/Leiomyoma

Benign and malignant smooth muscle tumors can also occur in the rectum. They are uncommon, but a limited review is useful. There is no specific staging system for rectal sarcomas. TNM staging classifications for other soft tissue sarcomas may be useful (Table 5) [25]. Common sites of metastases include the liver, lung and peritoneal cavity [25].

Table 5.

AJCC 2017 TNM for soft tissue sarcomas of the abdomen visceral organs.

| T Category |

| T1 Organ confined |

| T2 Tumor extension into tissue beyond organ |

| T2a invades serosa or visceral peritoneum |

| T2b extension beyond serosa (mesentery) |

| T3 Invades another organ |

| T4 Multifocal involvement |

| N Category |

| N0 no lymph node involvement or unknown lymph node status |

| N1 lymph node involvement present |

| M Category |

| M0 No metastasis |

| M1 Metastasis present |

Leiomyosarcoma [38] [38] is the most common sarcoma of the rectum [39,40]. LMS is less common than its benign counterpart, the leiomyoma, and the two lesions can be hard to distinguish on biopsy. There is a female predominance in LMS [7,41], and prior pelvic radiation is a known risk factor [7,42,43].

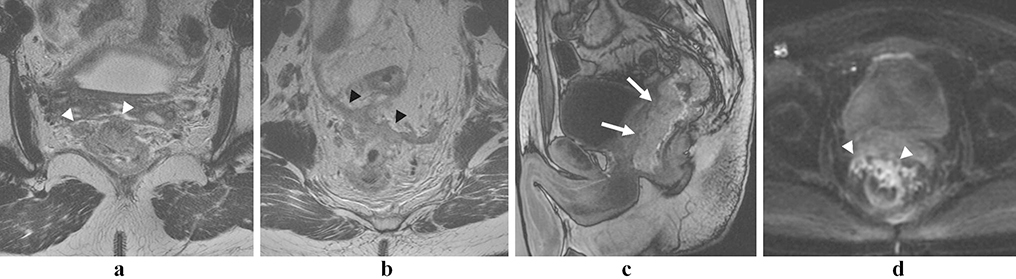

Rectal LMS is usually a polypoid intraluminal and may invade adjacent structures [44]. Nodal metastases are uncommon. On MRI, rectal LMS may be very similar in appearance to rectal GIST. The mass is often isointense to skeletal muscle on T1weighted images and heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted images; degrees of enhancement and necrosis are variable, with the latter being more common in larger tumors [7,44] (Figure 7).

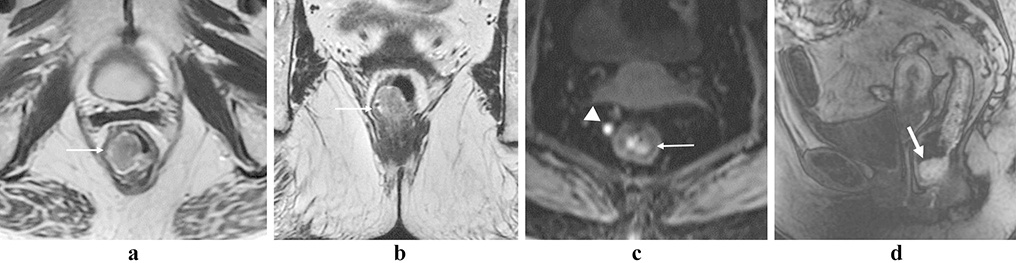

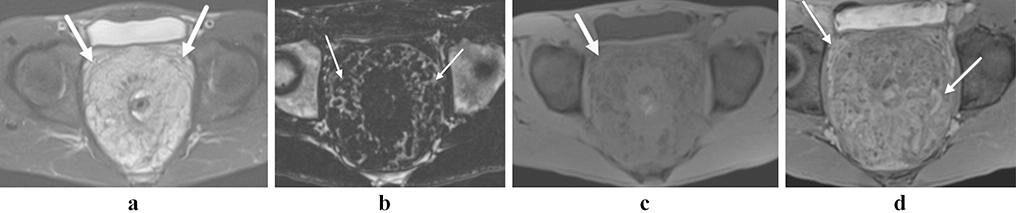

Figure 7:

Rectal leiomyosarcoma. 41-year-old woman with a lobulated, T2 hyperintense mass (arrows, a) with restricted diffusion (arrowheads; b, c). The lesion demonstrates a marked high signal intensity in T2 and internal areas of necrosis (* in d). The mass was a pathology proven leiomyosarcoma with extensive myxoid changes.

Prognosis is poor for these tumors and they tend to develop early hematogenous metastases; 5-year survival rates are between 20% and 40% [44].

Rectal angiosarcoma

Rectal angiosarcoma (AS) originates in the lymphatic and vascular endothelium [45]. These tumors are very rare and only a handful of case reports and series have been described [46,45,47]; thus, their natural history is unknown.

MRI findings have not been described for rectal AS. Case reports have described CT findings of rectal AS as a heterogeneously enhancing, eccentric bowel wall mass [46] or as a spiculated mass in rectal wall [47]. The example shown here is an infiltrative, partially circumferential mass with intermediate signal in T2- and T1-weighted images, restricted diffusion and early enhancement (Figure 8).

Figure 8:

Rectal angiosarcoma secondary to radiotherapy. 27-year-old man with Li-Fraumeni syndrome and history of multiple malignancies. Axial T2-weighted (a and b), sagittal dynamic arterial phase T1-weighted (c) and diffusion-weighted (d) MR images show a large partially circumferential and infiltrative mass along anterior rectal wall. The mass invades the prostate, seminal vesicles (white arrowheads in a and arrows in c) and anterior pelvic peritoneal reflection (black arrowheads in b). There is an intense early enhancement (arrows, c) and restricted diffusion (arrowheads, d).

Metastatic lesions of the rectum

Although rare, the rectum can be the site of metastases arising from cancers in another organ, e.g., the stomach, ovary and uterine cervix [48–50]. Metastases to the rectum have been reported as an intramural lesion [50], a polypoid mass [49] or circumferential thickening [48]. When there is a history of prior cancer or when in the presence of other metastases, it is important to remember that a mass in the rectum may in fact not be a primary lesion.

Intramural benign lesions

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare condition predominantly seen in young women, in which the lamina propria is replaced by fibrous tissue. Clinically, it can present with hematochezia and rectal prolapse, and on endoscopy it may appear as erythematous or ulcerated mucosa, sometimes with a polypoid or circumferential mass. Because of the clinical and endoscopic features, it is often initially thought to be a rectal cancer [51,52].

MRI features of SRUS have been described in the literature [51,52]. The MR appearance of SRUS may be variable, as either a polypoid or circumferential mass. Submucosal cysts within the mass have been described, but they are not consistently present [52]. Ultimately, histopathology is the reliable modality to make this rare diagnosis (Figures 9–10).

Figure 9:

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. 49-year-old male with rectal mass, presumed to be malignant on initial presentation. Axial (a, arrow) and sagittal (b, arrow) T2 images show rectal thickening with a polypoid mass. Post-contrast imaging shows enhancement within the lesion (c and d, arrows). Endoscopy shows an aggressive lesion arising from the rectal wall (e). Case courtesy of Perry Pickhardt, MD.

Figure 10.

Colitis cystica profunda. A variant of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in which there is cystic dilatation of the mucous glands of the colon. Multiplanar T2-weighted images (a-c, arrows) show multiple submucosal cysts in the rectum measuring up to 2 cm. There is an association with rectal prolapse, diarrhea, andemia and abdominal pain. Case courtesy of Perry Pickhardt, MD.

Rectal lipoma

Colonic lipomas are the most common benign non-epithelial tumors in the GI tract [7]. In the rectum, however, lipomas are very rare [53]. They may be submucosal (90%) or subserosal (10%) [7]. Patients are usually asymptomatic, but when the lipoma is > 2 cm, bleeding or constipation can occur [7,53,54]. On MRI, lipomas demonstrate signal loss with fat suppression and minimal or no enhancement [7] (Figure 11). If the patient is asymptomatic, no treatment is required [55].

Figure 11:

Rectal lipoma. 33-year-old male with an incidental mass. Axial T2-weighted (a), T1-weighted (b), and fat-suppressed T1-weighted (c) MR images show small exophytic lesion on rectal wall (a-c, arrows) with high signal intensity on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images and signal loss on fat-suppression sequence.

Rectal Hemangioma

Rectal hemangiomas are also rare, but in the colon the rectosigmoid region is the most common location [56]. Hemangiomas in the GI tract may be single or multiple and have syndrome associations (i.e., Maffucci, Klippel-Trénaunay) [22]. Recurrent, painless bleeding is common, and these lesions can be diagnosed at any age [57,22,58]. MRI may show a submucosal, pedunculated, polypoid or infiltrative lesion with very high T2-signal and adjacent serpiginous vessels [57]. Other clues that the lesion may be a hemangioma include the presence of pelvic phleboliths, often better seen on CT, and increased T2 signal intensity in the peri-rectal fat. Pre-operative embolization can be used to reduce the blood flow and reduce intraoperative bleeding if surgical resection is planned [59] (Figure 12).

Figure 12:

Rectal hemangioma. Axial T2-weighted fat suppressed (a), Dixon fat suppressed (b), pre contrast T1-weighted fat suppressed, and post contrast T1-weighted fat suppressed (d) MR images show markedly thickened rectosigmoid (arrows). There are serpiginous vessels (black arrows in d) and foci of bulk fat (white arrows in b).

Infection

Occasionally, infectious processes can mimic a colon or rectal mass. One such entity is basidiobolomycosis, a fungus that is present in arid climates. In the abdomen, it most commonly presents as focal bowel thickening and is often mistaken for a colonic mass or inflammatory bowel disease. It can also affect the liver and may be a cause of misdiagnosis. Biopsy should confirm the diagnosis [60] (Figure 13).

Figure 13:

Basidiobolomycosis. A rare fungal infection, more common in the southwest US, mimicking a circumferential rectal mass. Axial and sagittal T2-weighted images show the mass before treatment (a and b, arrows), with avid enhancement (c, arrow). After anti-fungal therapy, the mass has completely resolved (d and e). Case courtesy of Bobby Kalb, MD.

Extramural lesions

Endometriosis

In female patients, deep bowel invasive pelvic endometriosis can mimic a rectal mass clinically and on imaging [61]. The mass can be extrinsic or present with nodular thickening and most often involves the rectosigmoid colon. It can cause obstruction, and patients may present with bleeding and rectal pain [61]. The symptoms may be cyclic, related to the menstrual cycle.

Other features of deep pelvic endometriosis on MRI may provide clues that it is in fact not a conventional rectal mass, including the presence of an ovarian endometrioma, T2 hypointense thickening or nodularity of the pelvic ligaments, thickening of the torus uterine or a “kissing” morphology of the ovaries. An intermediate signal on T2-weighted images with foci of T1-hyperintensity is a classic finding. Restricted diffusion can be seen as well but does not distinguish deep pelvic endometriosis from other neoplasms [61,62]. When deep pelvic endometrial implants invade through the serosa into the muscular layer of the rectum or colon, it forms a classic “mushroom cap sign,” wherein low signal endometrial implants in the rectal wall are covered by a higher signal thickened mucosa that forms a “cap” [63] (Figure 14).

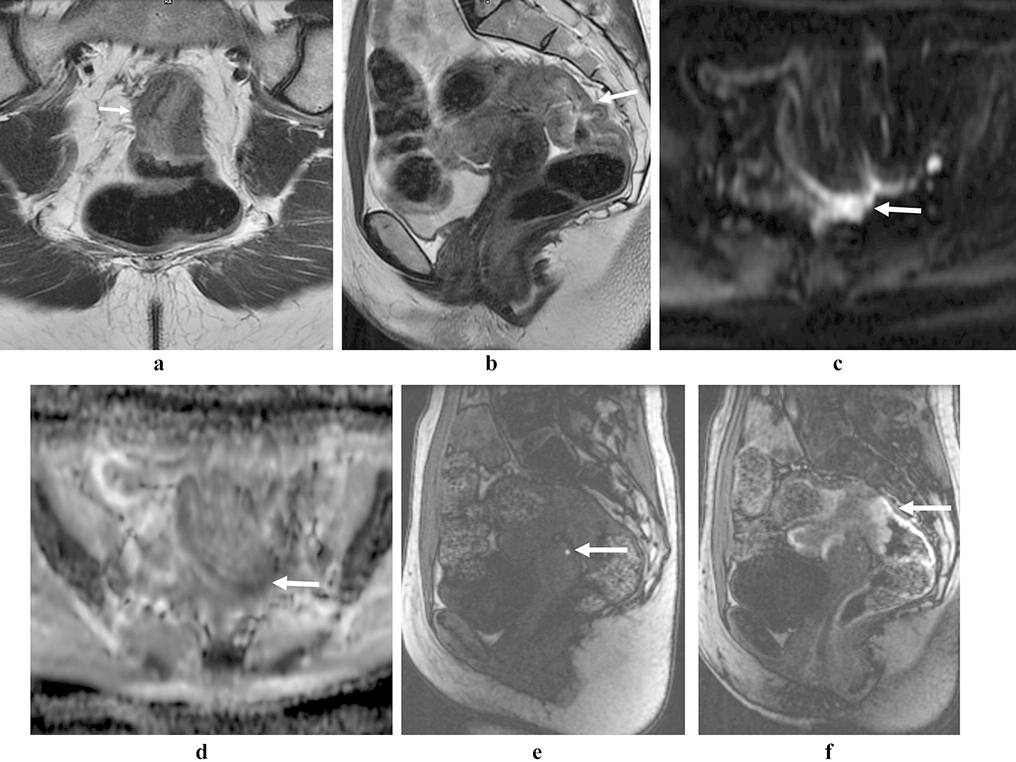

Figure 14:

Deep pelvic endometriosis mimicking a rectal mass. Axial (a) and sagittal (b) T2-weighted images show intermediate signal rectal thickening (arrows), with areas of corresponding restricted diffusion in the deep pelvis (c and d, arrows). Pre-contrast T1-weighted images (e) show intrinsic hyperintense signal, consistent with endometriosis. Post-contrast the mass-like thickening of the rectum enhances (f, arrow).

Local rectal invasion from an adjacent malignancy

Other primary malignancies in the pelvis can invade the rectum locally, and it can be difficult to ascertain the primary lesion. Other pelvic organs such as the uterus, ovaries and prostate may have aggressive biology with local rectal invasion.

Conclusion

The most common histological type of rectal neoplasms is adenocarcinoma; however, other histological types may occur within the rectum. Their characteristics are different, including risk factors, clinical manifestations, imaging findings, staging, treatment and prognosis. Familiarity with the MRI appearance of these uncommon rectal neoplasms is useful for abdominal radiologists (Table 6).

Table 6.

Important features of uncommon rectal tumors on imaging.

| Tumor type | Imaging features |

|---|---|

| NET | Superficial submucosal mass |

| Smaller than 1 cm | |

| Intense contrast enhancement | |

| Melanoma | High SI on T1WI (rectal lesion and lymph node) |

| Very low in the rectum | |

| Less perirectal desmoplasia | |

| GIST, leiomyosarcoma and leiomyoma | Submucosal mass, may have peritoneal or liver mets, without nodal metastases |

| Endophytic/exophytic configuration for GIST | |

| Well circumscribed lesion | |

| Without local invasion | |

| No lymphadenopathy | |

| Larger lesions may be heterogeneous | |

| Radiological differentiation is difficult | |

| Angiosarcoma | Irregular wall thickening |

| Heterogeneous enhancement | |

| Prominent vessels | |

| Lipoma | High SI on T1WI and T2WI |

| Signal loss on fat-suppression sequences | |

| Lymphoma | Heterogeneous high SI on T2WI |

| Homogeneous intermediate SI on T1WI | |

| Mild to moderate enhancement | |

| Often large without obstruction | |

| Hemangioma | Very high SI on T2WI |

| Progressive enhancement | |

| Vascular engorgement/changes in perirectal fat from increased vascularity | |

| Phleboliths (better seen on CT) | |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015, National Cancer Institute; (2018). https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/. Accessed October 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, Miller KD, Ma J, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A (2017) Colorectal Cancer Incidence Patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J Natl Cancer Inst 109 (8). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel UB, Taylor F, Blomqvist L, George C, Evans H, Tekkis P, Quirke P, Sebag-Montefiore D, Moran B, Heald R, Guthrie A, Bees N, Swift I, Pennert K, Brown G (2011) Magnetic resonance imaging-detected tumor response for locally advanced rectal cancer predicts survival outcomes: MERCURY experience. J Clin Oncol 29 (28):3753–3760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.9068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shihab OC, Taylor F, Salerno G, Heald RJ, Quirke P, Moran BJ, Brown G (2011) MRI predictive factors for long-term outcomes of low rectal tumours. Ann Surg Oncol 18 (12):3278–3284. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1776-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Pantongrag-Brown L, Buck JL, Herlinger H (1997) Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: radiographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 168 (1):165–172. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.1.8976941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghai S, Pattison J, Ghai S, O’Malley ME, Khalili K, Stephens M (2007) Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics 27 (5):1371–1388. doi: 10.1148/rg.275065151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purysko AS, Coppa CP, Kalady MF, Pai RK, Leao Filho HM, Thupili CR, Remer EM (2014) Benign and malignant tumors of the rectum and perirectal region. Abdom Imaging 39 (4):824–852. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0119-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanojevic GZ, Nestorovic MD, Brankovic BR, Stojanovic MP, Jovanovic MM, Radojkovic MD (2011) Primary colorectal lymphoma: An overview. World J Gastrointest Oncol 3 (1):14–18. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v3.i1.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quayle FJ, Lowney JK (2006) Colorectal lymphoma. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 19 (2):49–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-942344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee WK, Lau EW, Duddalwar VA, Stanley AJ, Ho YY (2008) Abdominal manifestations of extranodal lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 191 (1):198–206. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin C, Itti E, Luciani A, Haioun C, Meignan M, Rahmouni A (2010) Whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging in lymphoma. Cancer Imaging 10 Spec no A:S172–178. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2010.9029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, Lister TA, Alliance AL, Lymphoma G, Eastern Cooperative Oncology G, European Mantle Cell Lymphoma C, Italian Lymphoma F, European Organisation for R, Treatment of Cancer/Dutch Hemato-Oncology G, Grupo Espanol de Medula O, German High-Grade Lymphoma Study G, German Hodgkin’s Study G, Japanese Lymphorra Study G, Lymphoma Study A, Group NCT, Nordic Lymphoma Study G, Southwest Oncology G, United Kingdom National Cancer Research I (2014) Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 32 (27):3059–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsikitis VL, Wertheim BC, Guerrero MA (2012) Trends of incidence and survival of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in the United States: a seer analysis. Journal of Cancer 3:292–302. doi: 10.7150/jca.4502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung TP, Hunt SR (2006) Carcinoid and neuroendocrine tumors of the colon and rectum. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 19 (2):45–48. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-942343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JY, Hong SM (2016) Recent Updates on Neuroendocrine Tumors From the Gastrointestinal and Pancreatobiliary Tracts. Arch Pathol Lab Med 140 (5):437–448. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0314-RA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mocellin S, Nitti D (2013) Gastrointestinal carcinoid: epidemiological and survival evidence from a large population-based study (n = 25 531). Ann Oncol 24 (12):3040–3044. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A, Evans DB (2008) One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol 26 (18):3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstock B, Ward SC, Harpaz N, Warner RR, Itzkowitz S, Kim MK (2013) Clinical and prognostic features of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology 98 (3):180–187. doi: 10.1159/000355612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigues A, Castro-Pocas F, Pedroto I (2015) Neuroendocrine Rectal Tumors: Main Features and Management. GE Port J Gastroenterol 22 (5):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jpge.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baxi AJ, Chintapalli K, Katkar A, Restrepo CS, Betancourt SL, Sunnapwar A (2017) Multimodality Imaging Findings in Carcinoid Tumors: A Head-to-Toe Spectrum. Radiographics 37 (2):516–536. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim KW, Ha HK, Kim AY, Kim TK, Kim JS, Yu CS, Park SW, Park MS, Kim HJ, Kim PN, Kim JC, Lee MG (2004) Primary malignant melanoma of the rectum: CT findings in eight patients. Radiology 232 (1):181–186. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2321030909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee NK, Kim S, Kim GH, Jeon TY, Kim DH, Jang HJ, Park DY (2010) Hypervascular subepithelial gastrointestinal masses: CT-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 30 (7):1915–1934. doi: 10.1148/rg.307105028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H, Kim JH, Lim JS, Choi JY, Chung YE, Park MS, Kim MJ, Kim KW, Kim SK (2011) MRI findings of rectal submucosal tumors. Korean J Radiol 12 (4):487–498. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.4.487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Araujo PB, Cheng S, Mete O, Serra S, Morin E, Asa SL, Ezzat S (2013) Evaluation of the WHO 2010 grading and AJCC/UICC staging systems in prognostic behavior of intestinal neuroendocrine tumors. PLoS One 8 (4):e61538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amin MBE SB; Greene FL; et al. (2017) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer; 8th Edition [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chae WY, Lee JL, Cho DH, Yu CS, Roh J, Kim JC (2016) Preliminary Suggestion about Staging of Anorectal Malignant Melanoma May Be Used to Predict Prognosis. Cancer Res Treat 48 (1):240–249. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li P, Liu J (2016) Diagnostic value of MRI and computed tomography in anorectal malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res 26 (1):46–50. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postow MA, Hamid O, Carvajal RD (2012) Mucosal melanoma: pathogenesis, clinical behavior, and management. Curr Oncol Rep 14 (5):441–448. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0244-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ologun GO, Stevenson Y, Shen A, Rana NK, Hussain A, Bertsch D, Cagir B (2017) Anal Melanoma in an Elderly Woman Masquerading as Hemorrhoid. Cureus 9 (11):e1880. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohli S, Narang S, Singhal A, Kumar V, Kaur O, Chandoke R (2014) Malignant melanoma of the rectum. J Clin Imaging Sci 4:4. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.126031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matalon SA, Mamon HJ, Fuchs CS, Doyle LA, Tirumani SH, Ramaiya NH, Rosenthal MH (2015) Anorectal Cancer: Critical Anatomic and Staging Distinctions That Affect Use of Radiation Therapy. Radiographics 35 (7):2090–2107. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015150037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang M, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Sheng W, Lian P, Liu F, Cai S, Xu Y (2013) Tumour diameter is a predictor of mesorectal and mesenteric lymph node metastases in anorectal melanoma. Colorectal Dis 15 (9):1086–1092. doi: 10.1111/codi.12250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bello DM, Smyth E, Perez D, Khan S, Temple LK, Ariyan CE, Weiser MR, Carvajal RD (2013) Anal versus rectal melanoma: does site of origin predict outcome? Dis Colon Rectum 56 (2):150–157. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827901dd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang ZX, Zhang SJ, Peng WJ, Yu BH (2013) Rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: imaging features with clinical and pathological correlation. World J Gastroenterol 19 (20):3108–3116. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yasui M, Tsujinaka T, Mori M, Takahashi T, Nakashima Y, Nishida T, Kinki GSG (2017) Characteristics and prognosis of rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an analysis of registry data. Surg Today. doi: 10.1007/s00595-017-1524-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu MH, Lee JM, Baek JH, Han JK, Choi BI (2014) MRI features of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 203 (5):980–991. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levy AD, Remotti HE, Thompson WM, Sobin LH, Miettinen M (2003) Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: radiologic features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics 23 (2):283–304, 456; quiz 532. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaskin CM, Helms CA (2004) Lipomas, lipoma variants, and well-differentiated liposarcomas (atypical lipomas): results of MRI evaluations of 126 consecutive fatty masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol 182 (3):733–739. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nassif MO, Trabulsi NH, Bullard Dunn KM, Nahal A, Meguerditchian AN (2013) Soft tissue tumors of the anorectum: rare, complex and misunderstood. J Gastrointest Oncol 4 (1):82–94. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thiels CA, Bergquist JR, Krajewski AC, Lee HE, Nelson H, Mathis KL, Habermann EB, Cima RR (2017) Outcomes of Primary Colorectal Sarcoma: A National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) Review. J Gastrointest Surg 21 (3):560–568. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3347-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoshino N, Hida K, Kawada K, Sakurai T, Sakai Y (2017) Transanal total mesorectal excision for a large leiomyosarcoma at the lower rectum: a case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep 3 (1):13. doi: 10.1186/s40792-017-0289-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oruc MT, Mayir B, Bilecik T, Sakar A, Erinekci AR (2015) Rectal leiomyosarcoma, late complication of pelvic radiotherapy. Int J Colorectal Dis 30 (4):571–572. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2020-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Futuri S, Donohoe K, Spaccavento C, Yudelman I (2014) Rectal leiomyosarcoma: a rare and long-term complication of radiation therapy. BMJ Case Rep 2014. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-205240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ouh YT, Hong JH, Min KJ, So KA, Lee JK (2013) Leiomyosarcoma of the rectum mimicking primary ovarian carcinoma: a case report. J Ovarian Res 6 (1):27. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaballah AH, Jensen CT, Palmquist S, Pickhardt PJ, Duran A, Broering G, Elsayes KM (2017) Angiosarcoma: clinical and imaging features from head to toe. Br J Radiol 90 (1075):20170039. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown CJ, Falck VG, MacLean A (2004) Angiosarcoma of the colon and rectum: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum 47 (12):2202–2207. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0698-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tardio JC, Najera L, Alemany I, Martin T, Castano A, Perez-Regadera JF (2009) Rectal angiosarcoma after adjuvant chemoradiotherapy for adenocarcinoma of the rectum. J Clin Oncol 27 (27):e116–117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Derin D, Eralp Y, Guney N, Ozluk Y, Topuz E (2008) Ovarian carcinoma with simultaneous breast and rectum metastases. Onkologie 31 (4):200–202. doi: 10.1159/000119121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tural D, Selcukbiricik F, Ercaliskan A, Inanc B, Gunver F, Buyukunal E (2012) Metachronous rectum metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Med 2012:726841. doi: 10.1155/2012/726841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu YC, Yang CF, Hsu CN, Hsieh TC (2013) Intramural metastases of rectum from carcinosarcoma (malignant mullerian mixed tumor) of uterine cervix. Clin Nucl Med 38 (2):137–139. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318266d4bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amaechi I, Papagrigoriadis S, Hizbullah S, Ryan SM (2010) Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome mimicking rectal neoplasm on MRI. The British journal of radiology 83 (995):e221–224. doi: 10.1259/bjr/24752209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blanco F, Frasson M, Flor-Lorente B, Minguez M, Esclapez P, Garcia-Granero E (2011) Solitary rectal ulcer: ultrasonographic and magnetic resonance imaging patterns mimicking rectal cancer. European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology 23 (12):1262–1266. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834b0dee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martellucci J, Civitelli S, Tanzini G (2011) Transanal resection of rectal lipoma mimicking rectal prolapse: description of a case and review of the literature. ISRN Surg 2011:170285. doi: 10.5402/2011/170285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fernandes J, Libanio D, Giestas S, Araujo T, Martinez-Ares D, Certo M, Lopes L (2018) Giant symptomatic rectal lipoma resected by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy 50 (3):E63–E64. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arora R, Kumar A, Bansal V (2011) Giant rectal lipoma. Abdom Imaging 36 (5):545–547. doi: 10.1007/s00261-010-9668-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levy AD, Abbott RM, Rohrmann CA Jr., Frazier AA, Kende A (2001) Gastrointestinal hemangiomas: imaging findings with pathologic correlation in pediatric and adult patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 177 (5):1073–1081. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.5.1771073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoo S (2011) GI-Associated Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 24 (3):193–200. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan MC, Mutch MG (2006) Hemangiomas of the pelvis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 19 (2):94–101. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-942350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carvalho RGFMRU G; Guzela VR; Joviliano EE; Féres O; Rocha JJR (2014) Preoperative embolization of a cavernous hemangioma of the rectum. Journal of Coloproctology 34 (1):52–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcol.2013.12.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flicek KT, Vikram HR, De Petris GD, Johnson CD (2015) Abdominal imaging findings in gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. Abdom Imaging 40 (2):246–250. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0212-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ganguly A, Meredith S, Probert C, Kraecevic J, Anosike C (2016) Colorectal cancer mimics: a review of the usual suspects with pathology correlation. Abdominal Radiology 41 (9):1851–1866. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0771-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siegelman ES, Oliver ER (2012) MR Imaging of Endometriosis: Ten Imaging Pearls. RadioGraphics 32 (6):1675–1691. doi: 10.1148/rg.326125518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arevalo N, Mendez R (2018) “Mushroom cap” sign in deep rectosigmoid endometriosis. Abdom Radiol (NY) 43 (11):3201–3203. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1596-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]