Abstract

Thyroid cancer cells have a high amino acid demand for proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Amino acids are taken up by thyroid cancer cells, both thyroid follicular cell and thyroid parafollicular cells (commonly called “C-cells”), via amino acid transporters. Amino acid transporters up-regulate in many cancers, and their expression level associate with clinical aggressiveness and prognosis. This is the review to discuss the therapeutic potential of amino acid transporters and as molecular targets in thyroid cancer.

Keywords: Thyroid neoplasms; Large neutral amino acid-transporter 1; Amino acid transport systems; 2-amino-3-(4-((5-amino-2-phenylbenzo(d)oxazol-7-yl)methoxy)-3,5-dichlorophenyl)propanoic acid; Boron neutron capture therapy; Proto-oncogene proteins c-myc

INTRODUCTION

Amino acids play essential roles in protein synthesis, which promotes cell growth and proliferation in both normal cells and cancer cells [1–4]. Nonessential amino acids are synthesized from essential amino acids; however, essential amino acids cannot be synthesized de novo. Amino acids, particularly essential amino acids, are required to be taken up by various cells via different amino acid transporters. Among the 20 standard amino acids, 11 are nonessential: alanine, asparagine, aspartate, cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, tyrosine, and arginine; the remaining nine are essential: histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine.

Thyroid cancer (TC) is the most frequent endocrine carcinoma, with an incidence of 12.9, 25.8, and 64.1 per 100,000 individuals in the USA (2011 to 2015), Puerto Rico (2011 to 2015), and Korea (2008 to 2010), respectively [5,6]. Most TCs are associated with a low mortality risk, with gradual progression, no clinical metastasis, and an excellent prognosis [7]. Some papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTCs) such as microcarcinoma with very low mortality risk may not require surgical treatment (clinical active surveillance) [8–10]. However, several PTCs associated with a high mortality risk require treatment including surgery, 131I-radiotherapy, and chemotherapy targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor. In particular, anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) is associated with a high mortality risk, with a 3-year survival ratio of <20% [11,12]. This review focuses on amino acid transporters as molecular therapeutic targets and their clinical applications for TC.

AMINO ACID TRANSPORTERS AND THYROID CANCER

Transporters are classified into two broad categories based on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) dependence [13]. ATP-dependent transporters, known as ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, hydrolyze ATP to obtain energy for transmembrane translocation of their substrates. Transporters without an ATPase domain, called solute carriers (SLCs), facilitate diffusive transport. Most amino acid transporters are SLCs, and belong to several groups based on their substrates and sodium dependency; however, they have been classified in accordance with their sequence homology. L-type amino acid transporters (LATs) are categorized as system L transporters, which transport neutral amino acids including alanine, asparagine, cysteine, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, tyrosine, isoleucine, leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, and valine.

Among amino acid transporters, L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1; SLC7A5), LAT2 (SLC7A8), LAT3 (SLC43A1), LAT4 (SLC43A2), alanine-serine-cysteine transporter (ASCT, SLC1A5), amino acid transporter B(0,+) (ATB0+, SLC6A14), cystine/glutamate exchanger (xCT, SLC7A11), and cationic amino acid transporter 3 (CTR3, SLC7A3) are associated with various cancers (Table 1). LAT1 and LAT2 are the first and second system L amino acid transporter isoforms, discovered in 1998 [14,15] and 1999 [16–18], respectively. In healthy individuals, LAT1 is expressed in the Sertoli cells, kidney distal tubules, pancreatic islet cells, and gastrointestinal organs including the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon [19]. LAT1 is demonstrated strong upregulation in many cancers, and higher upregulation of LAT1 associate with poor survival in various cancers including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), breast, lung, esophagus, and biliary duct cancers [20]. Furthermore, LAT1 suppression decreases cell growth and proliferation through attenuation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling in many cancer cells [20,21], and impaired migration and invasion of gastric and prostate cancer cells [22,23]. Thus, LAT1 is a strong candidate for molecular-targeted therapy for various cancers. Furthermore, TC cells reportedly display LAT1 upregulation, thus rendering LAT1 a novel molecular therapeutic target [24–27].

Table 1.

Amino Acid Transporters Associated with Thyroid Cancer

| Protein | Gene | Major substrates | Co-activator | Expression in thyroid cancer | Outcome on overexpression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAT1 | SLC7A5 | Leu, Ile, Val, Phe, Met, His, Tyr, Trp | 4F2hc/CD98 | Upregulation in PTC [24] ATC [24,26] MTC [27] |

Poor in PTC [24,25] ATC [26] |

| LAT2 | SLC7A8 | Ala, Asn, Cys, Gln, Gly, Ile, Leu, Met, Phe , Ser, Thr, Tyr, Val | 4F2hc/CD98 | Upregulation PTC [30], MTC [27] No change in FTC, ATC [30] |

No data |

| LAT3 | SLC43A1 | Leu, Ile, Val, Phe, Met | No | No data | No data |

| LAT4 | SLC43A2 | Leu, Ile, Val, Phe, Met | No | Downregulation in PTC, FTC, PDTC, ATC [30] |

No data |

| ASCT2 | SLC1A5 | Ala, Ser, Cys, Thr, Gln, Asn, Glu | No | Upregulation in MTC [39] Nochange in PTC, FTC, PDTC, ATC [39] |

No change in alla [39] |

| ATB0+ | SLC6A14 | Ala, Ser, Cys, His, Met, Ile, Leu, Val, Phe, Tyr, Trp | No | No data | No data |

| xCT | SLC7A11 | Gln | 4F2hc/CD98 | No data | Poor in PTC [25] |

| CTR3 | SLC7A3 | Arg, Lys | No | No data | Poor in PTC [25] |

LAT1, L-type amino acid transporter 1; His, histidine; Met, methionine; Leu, leucine; Ile, isoleucine, Val, valine; Phe, phenylalanine; Ala, alanine; Asn, asparagine; Cys, cysteine; Gln, glutamine; Gly glycine; Ser, serine; Thr, threonine; Trp, tryptophan; Tyr, tyrosine; Arg, arginine; Lys, lysine; PTC, papillary thyroid cancer; ATC, anaplastic thyroid cancer; ASCT, alanine-serine-cysteine transporter; MTC, medullary thyroid cancer; FTC, follicular thyroid cancer; PDTC, poorly differentiated thyroid cancer; ATB, amino acid transporter B; xCT, cystine/glutamate exchanger; CTR, cationic amino acid transporter.

The survival was calculated in thyroid cancer, in the following subtypes: PTC, FTC, MTC, PDTC, and ATC.

LAT2 has similar expression patterns as LAT1, being primarily expressed in gastrointestinal organs and the kidney proximal tubule [19]. LAT2-knockout mice display a mild phenotype and almost no visible symptoms except for aminoaciduria [28]. Both LAT1 and LAT2 contain 12 transmembrane domains that form a channel for their substrates [29]. However, it remains unclear whether LAT2 expression levels vary during TC. Badziong et al. [30] reported that LAT2 is upregulated in PTC but its levels remain unchanged in follicular thyroid cancer (FTC) and ATC. However, Barollo et al. [27] reported LAT2 downregulation in medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), a neuroendocrine tumor. Thus far, data on LAT2 expression in TC are controversial.

LAT3 has been isolated through expression cloning from hepatocarcinoma cells [31] and its primary structure is reportedly identical to that of prostate cancer over-expressed gene 1(POV1), which is reportedly upregulated in prostate cancer [32]. The substrate selectivity of LAT3 is similar to that of LAT1; its substrates include isoleucine, leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, and valine (Table 1) [31]. LAT3 is upregulated in the liver, skeletal muscle, and pancreas [31] and apparently serves as a critical transporter in several cancers. LAT3 knockdown significantly inhibits the leucine uptake, cell proliferation, and metastasis in human prostate cancer cell lines in vitro [33]. LAT3 is potentially associated with cancer cell proliferation and metastasis; however, no study has reported the expression of LAT3 in TC.

LAT4 was identified on the basis of its sequence homology with LAT3 [34]. LAT4 is upregulated in peripheral blood, the placenta, kidney, and spleen [34]. Badziong et al. [30] reported that LAT4 is downregulated in PTC, FTC, and ATC. In contrast, LAT4 is overexpressed in Graves’ disease. However, the role of LAT4 in thyroid carcinogenesis remains unclear.

ASCT2, an Na+-dependent neutral amino acid transporter encoded by SLC1A5, is predominantly localized at the cell membrane [35] and mediates the exchange of amino acid substrates, particularly mediating rapid glutamine uptake in proliferating cancer cells [36]. ASCT2 upregulation worsens the prognosis of HNSCC, clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma, gastric cancer, triple-negative breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and other cancers [37,38]. Kim et al. [39] (2016) reported ASCT2 upregulation in MTC originating from parafollicular cells but not in other TCs of follicular origin, including PTC, FTC, poorly differentiated carcinoma, and ATC.

ATB0+ is a member of the Na+- and Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporter family, and is upregulated in the lungs, fetal lungs, trachea, and salivary gland. ATB0+ transports both neutral and cationic amino acids, and has approximately 60% amino acid similarity with glycine transporters GLYT1 and GLYT2 [40]. The blockade of ATB0+ is associated with a reduction in pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, indicating the potential of ATB0+ as a drug target in cancer chemotherapy [41]. However, the role of ATB0+ in TC remains unclear.

xCT is a cysteine/glutamate transporter, which plays a key role in glutathione synthesis. xCT overexpression decreases endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and increases the migration and invasion of glioblastoma cells [42]. Furthermore, xCT accelerates tumor growth and tumor associated-seizures and helps predict the outcomes of patients with malignant glioma [43]. In PTC, xCT upregulation was reportedly associated with poor survival [25].

CTR3 is a sodium-independent cationic amino acid transporter, which is glycosylated and localized at the plasma membrane [44]. Shen et al. [25] reported that SLC7A3 expression is associated with extrathyroidal extension, higher cancer stage, BRAF, RAS mutation, and mortality in PTC.

Though the protein expression of amino acid transporters alters in many cancers including TC, gene mutations of amino acid transporters are still unclear. The point mutations in SLC7A5 were reported just one case with a missense mutation in breast cancer [45]. Bik-Multanowski and Pietrzyk [46] screened for SLC7A5 mutations in phenylketonuric patients and three polymorphism and one new mutation (G41D) were detected [47]. Recently, SLC7A8 expression was showed in the mouse inner ear and that abolish of LAT2 resulted in age-related hearing loss [48]. They also reported significant decreases in LAT2 transport activity for patient’s variants (p.V302I, p.R418H, p.T402M, and p.V460E) in SLC7A8. Gene mutations of amino acid transporters according to TC has not been clarified at the moment.

LAT1 AND THYROID CANCER

LAT1 is one of the most appropriate candidates for molecular-targeted therapy for TC from follicular cell (Table 2). Shen et al. [25] reported that a poor prognosis is associated with SLC7A5 upregulation in PTC. Hafliger et al. [24] and Enomoto et al. [26] reported the therapeutic potential of the selective LAT1 inhibitor JPH203 in TC. Hafliger et al. [24] reported that LAT1 is overexpressed in PTC and ATC, and LAT1 overexpression is associated with a poor prognosis of PTC [24]. Enomoto et al. [26] reported that LAT1 and co-expressed 4F2hc are overexpressed in ATC patients through immunohistochemical analyses, and LAT1 overexpression is associated with poor outcomes in ATC. Both studies confirmed that JPH203 inhibits the proliferation of human TC cell lines in vitro. Furthermore, Hafliger et al. [24] and Enomoto et al. [26] reported the antitumor effect of JPH203 in different in vivo models, e.g., v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF)V600E/4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA)H1047R-double mutant mice that constitute spontaneous ATC models with an activated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway, and a xenograft mouse model established using ATC cell line 8505C containing BRAF, PI3K3R1/2, and p53 mutations [48,49]. JPH203 can thus be considered a highly reliable therapeutic candidate for TC, particularly ATC.

Table 2.

Studies Reporting the Role of LAT1 in Thyroid Cancer

| Hafliger et al. [24] | Enomoto et al. [26] | Barollo et al. [27] | Shen et al. [25] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | PTC, ATC | ATC | MTC | PTC |

|

| ||||

| Clinical sample analysis | mRNA | IHC | mRNA, IHC | mRNA |

|

| ||||

| Survival analysis | PTC | ATC | ||

|

| ||||

| In vitro study | ||||

| Inhibitors | JPH203 | JPH203, siRNA | ||

| Cell cycle analysis | G0/G1 cell cycle arrest | |||

| Apoptosis analysis | TUNEL positive | |||

|

| ||||

| In vivo mouse study | Conditional KO | xenograft model | ||

LAT1, L-type amino acid transporter 1; PTC, papillary thyroid cancer; ATC, anaplastic thyroid cancer; MTC, medullary thyroid cancer; IHC, immunohistochemistry; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling; KO, knock-out.

Furthermore, LAT1 may be considered a therapeutic target in MTC, which originates from parafollicular cells. Barollo et al. [27] confirmed that LAT1 overexpression in MTC paralleled glucose transporter 1 overexpression and that LAT1 is overexpressed in an MTC cell line, TT, through Western blotting. However, it remains unclear whether inhibiting overexpressed LAT1 attenuates MTC proliferation.

In numerous cancers, LAT1 upregulation is associated with metastasis. In non-small-cell lung cancers, lymph node metastasis-positive squamous cell carcinomas express LAT1, while no positive LAT1 signals have been reported in non-metastatic cells [50]. A group of cells with LAT1 upregulation displayed larger metastatic lesions in gastric carcinoma [51]. LAT1 expression in neuroendocrine tumors was significantly associated with lymph node metastasis [52]. The functional significance of LAT1 in metastasis has been reported. RNAi-mediated LAT1 knockdown inhibited the migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells [23] and a cholangiocarcinoma cell line [53]. 2-Aminobicyclo-(2,2,1)-heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH) reportedly inhibited proliferation and migration in a human epithelial ovarian cancer cell line [54]. Although the positive association between cancer metastasis and LAT1 expression has been reported, no studies have indicated the association between LAT1 overexpression and TC metastasis thus far.

CLINICAL APPLICATION OF LAT1-TARGETING AGENTS

LAT1 inhibitors

BCH is a prototypical non-selective LAT1 inhibitor [55]. BCH inhibits LAT1, thus inhibiting the uptake of L-leucine with an IC50 of 73.1 to 78.8 μM in three cancer cell lines (human oral epidermoid carcinoma, human osteogenic sarcoma, and rat glioma cells) [56]. Because high BCH concentrations are required for inhibiting highly proliferous cancer cells, no clinical trials have been performed thus far. JPH203 (KYT-0353) is a selective LAT1 inhibitor with an IC50 of 0.06 μM for L-leucine [57], strongly inhibiting HT-29 colon cancer cell growth, with an IC50 value of 4.1 μM. In 2017, Kongpracha et al. [58] synthesized another LAT1 inhibitor, SKN103, based on the structure of T3 and reported the inhibition of L-leucine uptake of 4 human cell lines (pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, cervix adenocarcinoma, and adenocarcinomic alveolar basal epithelia) and inhibition of tumor cell growth in two cell lines (pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma); however, no in vivo assays have been conducted thus far.

JPH203 was recently evaluated in a first-in-human phase 1 clinical trial (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry UMIN000016546). Okano et al. [59] reported among 17 patients with advanced solid tumors, one patient with biliary tract cancer presented a partial response and five patients with biliary tract cancer or colorectal cancer presented stable disease. Common treatment-related adverse events included malaise, nausea, and a grade 1 or 2 fever. JPH203 is currently being evaluated in a phase 2 clinical trial among patients with advanced biliary tract cancers (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry UMIN000034080). To our knowledge, no LAT1 inhibitor has been clinically assessed for TC, in both follicular cell and parafollicular cells thus far.

Diagnosis via positron emission tomography

Imaging analysis of TC has largely been dependent on radioactive iodine such as 123I and 131I scintigraphy. Positron emission tomography (PET) has greater sensitivity than single-photon imaging (planar and single photon emission computed tomography [SPECT]) [60]. Upon uptake of radioactive iodine into follicular cells via the sodium/iodide symporter, positron-labeled 124I was developed as a PET tracer to detect TC. These primarily help detect metastatic and recurrent foci of TC after total thyroidectomy, through postoperative 131I administration. 2-18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (18F-FDG) is a most common tracer for visualizing glucose metabolism through PET. Cancer imaging via 18F-FDG PET is based on the observation that most cancers, including TC, metabolize glucose at an abnormally high rate [61]. Therefore, evaluation of glucose metabolism through 18F-FDG PET helps differentiate between malignant and benign tumors, staging and diagnosis, treatment, evaluation of therapeutic outcomes, prediction of prognosis, responsiveness assessment, and relapse [62,63]. Moreover, high 18F-FDG accumulation is associated with low 131I accumulation based on dedifferentiation of the follicular thyroid cell (flip-flop) [64,65]. However, 18F-FDG PET sometimes yields false-positive results, especially in Hashimoto thyroiditis and Graves’ disease, and false-negative results for brain metastasis because of their high background levels [62,66].

To resolve these issues, amino acid assessment has gained increasing attention as alternative probes instead of glucose measurement via 18F-FDG. Representative amino acids or their analogs developed as PET probes are L-3-18F-fluoro-α-methyl tyrosine (18F-FAMT), 6-18F-fluoro-L-3,4-dihydroxy-phenylalanine (18F-DOPA), L-[11C-methyl] methionine (11C-MET), O- (2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-l-tyrosine (18F-FET), and 18F-NKO-035. 18F-NKO-035, a LAT1-selective substrate, was recently developed as an anti-cancer agent at Osaka University [67]. A clinical trial revealed that NKO-035 has high affinity for LAT1 (Japanese Registry of Clinical Trials, jRCTs051190057). Of these, 18F-FDOPA and 11C-MET have been assessed among TC patients [68,69]. 18F-FDOPA PET/CT is a suitable modality for detecting metastatic, persistent, and residual MTC; however, 18F-FDG PET/CT may be considered for aggressive MTC in cases displaying signs of dedifferentiation or rapidly rising CEA levels [68,69]. Thus far, 11C-MET PET has not been proven superior to 18F-FDG PET in detecting recurrent differentiated TC [70]. However, few studies have focused on amino acid transporters in TC. Further studies are required to determine the utility of amino acid transporter imaging in TC.

Boron neutron capture therapy

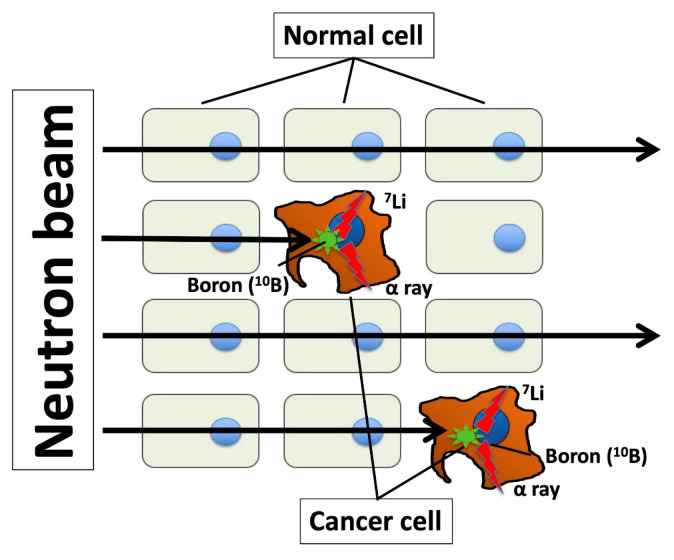

Boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) is an anticancer therapy using high linear energy transfer alpha particles. Particle radiation is generated by fission reactions when an irradiated thermal neutron beam collides with boron captured by a malignant tumor (Fig. 1). The traveling distance of particle radiation is limited to approximately 5 to 9 μm, and it then disrupts only cancer cells capturing boron without damaging other cells around target cells [71,72]. The success of BNCT depend on 10B compound concentration of tumor/normal tissue ratios (T/N ratio). This difficult task could be performed by synthesizing a boron compound that is selectively delivered by LAT1. Indeed, p-boronophenylalanine (BPA), a boron compound commonly used in BNCT, is incorporated in cancer cells through LAT1 [73–75], which serves as an optimal mediator for boron delivery. BNCT has achieved certain clinical outcomes in case of high T/N ratio in boron concentration; however, it requires a large-scale nuclear reactor to generate neutrons. Nonetheless, a compact accelerator has been developed as an alternative to a nuclear reactor, and it can be installed in a hospital, thus facilitating the easy application of BNCT [76]. Dagrosa et al. [77–79] reported the application of BNCT for undifferentiated TC in vitro and in an in vivo mouse model. However, the clinical advantages of BNCT in TC management remain unknown.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the nuclear capture reaction in Boron neutron capture therapy. On irradiation of the 10B compound, p-boronophenylalanine (BPA), with thermal neutrons, alpha particles and lithium nuclei are obtained, subsequently damaging cancer cells selectively. The track ranges of the two emitted particles within the body are approximately 5 to 9 μm, and this distance is not greater than the diameter of the cancer cells. The emitted particles thus damage only the cancer cell nuclei and do not approach adjacent normal cells. Therefore, damage is suppressed in normal cells, since they do not take up BPA via L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1), and cancer cells are selectively damaged.

REGULATION OF LAT1

MYC, a proto-oncogene, is upstream of LAT1. The consensus binding sequence of MYC is located at the LAT1 promoter [80]. Moreover, MYC knockdown downregulates LAT1 in human pancreatic cancer cell lines [80]. MYC is usually expressed at baseline levels in healthy adults [81]; however, MYC overexpression owing to gene amplification, gene translocation, or other gene mutations [82] results in malignant transformation. Notably, MYC is upregulated in patients with TC including ATC, and MYC overexpression promotes TC pathogenesis [83–86]. Therefore, MYC is a LAT1 regulator, partly even in TC.

Furthermore, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 2 regulates LAT1. HIF2a, an isoform of the HIF family regulating responses to hypoxia, binds to the LAT1 promoter and upregulates LAT1 in renal carcinoma and neuronal cells [87,88]. Exogenous HIF2a upregulation induces LAT1 expression in the lung and liver tissues, wherein LAT1 is generally downregulated [87]. Furthermore, aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) binds to its consensus binding sequence in LAT1 and induces LAT1 expression in breast cancer cell lines [89]. The NOTCH signaling pathway and activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) also be candidate an important upstream regulator of LAT1 in human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and prostate cancer, respectively [33,90]. The knockdown or small molecule inhibition of EZH2, the epigenetic regulator enhancer of zeste homolog 2, leads to de-repression of RXRα resulting in reduced LAT1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer model [91]. However, the effect of these factors on LAT1 expression in TC is still unclear.

CONCLUSIONS

Numerous studies have reported the crucial role of amino acids and their transporters in various cancers; however, relatively few studies have determined their potential in the clinical management of TC. A detailed understanding of amino acid metabolism in different cancers would facilitate the development of curative therapy for cancers. Amino acid transporters, especially LAT1, are potential targets for molecular-targeted therapy, imaging, and diagnosis in numerous cancers including TC. The clinical implications of amino acid transporters have recently been reported. Further studies are required to clarify potential molecular targets for treating TC.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

This study was partially supported by Takeda Science Foundation and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP20K08939 (PI: Keisuke Enomoto).

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhu J, Thompson CB. Metabolic regulation of cell growth and proliferation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:436–50. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0123-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pages M, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Cancer metabolism: a therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:11–31. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He Y, Gao M, Tang H, Cao Y, Liu S, Tao Y. Metabolic intermediates in tumorigenesis and progression. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1187–99. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.33496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vettore L, Westbrook RL, Tennant DA. New aspects of amino acid metabolism in cancer. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:150–6. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0620-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tortolero-Luna G, Torres-Cintron CR, Alvarado-Ortiz M, Ortiz-Ortiz KJ, Zavala-Zegarra DE, Mora-Pinero E. Incidence of thyroid cancer in Puerto Rico and the US by racial/ethnic group, 2011–2015. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:637. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5854-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn HS, Kim HJ, Kim KH, Lee YS, Han SJ, Kim Y, et al. Thyroid cancer screening in South Korea increases detection of papillary cancers with no impact on other subtypes or thyroid cancer mortality. Thyroid. 2016;26:1535–40. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iniguez-Ariza NM, Brito JP. Management of low-risk papillary thyroid cancer. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2018;33:185–94. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2018.33.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito Y, Uruno T, Nakano K, Takamura Y, Miya A, Kobayashi K, et al. An observation trial without surgical treatment in patients with papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid. Thyroid. 2003;13:381–7. doi: 10.1089/105072503321669875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Inoue H, Fukushima M, Kihara M, Higashiyama T, et al. An observational trial for papillary thyroid microcarcinoma in Japanese patients. World J Surg. 2010;34:28–35. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugitani I, Toda K, Yamada K, Yamamoto N, Ikenaga M, Fujimoto Y. Three distinctly different kinds of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma should be recognized: our treatment strategies and outcomes. World J Surg. 2010;34:1222–31. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0359-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salehian B, Liem SY, Mojazi Amiri H, Maghami E. Clinical trials in management of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; progressions and set backs: a systematic review. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2019;17:e67759. doi: 10.5812/ijem.67759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugitani I, Miyauchi A, Sugino K, Okamoto T, Yoshida A, Suzuki S. Prognostic factors and treatment outcomes for anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: ATC Research Consortium of Japan cohort study of 677 patients. World J Surg. 2012;36:1247–54. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1437-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hediger MA, Clemencon B, Burrier RE, Bruford EA. The ABCs of membrane transporters in health and disease (SLC series): introduction. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanai Y, Segawa H, Miyamoto Ki, Uchino H, Takeda E, Endou H. Expression cloning and characterization of a transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23629–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mastroberardino L, Spindler B, Pfeiffer R, Skelly PJ, Loffing J, Shoemaker CB, et al. Amino-acid transport by heterodimers of 4F2hc/CD98 and members of a permease family. Nature. 1998;395:288–91. doi: 10.1038/26246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossier G, Meier C, Bauch C, Summa V, Sordat B, Verrey F, et al. LAT2, a new basolateral 4F2hc/CD98-associated amino acid transporter of kidney and intestine. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34948–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segawa H, Fukasawa Y, Miyamoto K, Takeda E, Endou H, Kanai Y. Identification and functional characterization of a Na+-independent neutral amino acid transporter with broad substrate selectivity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19745–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pineda M, Fernandez E, Torrents D, Estevez R, Lopez C, Camps M, et al. Identification of a membrane protein, LAT-2, that co-expresses with 4F2 heavy chain, an L-type amino acid transport activity with broad specificity for small and large zwitterionic amino acids. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19738–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakada N, Mikami T, Hana K, Ichinoe M, Yanagisawa N, Yoshida T, et al. Unique and selective expression of L-amino acid transporter 1 in human tissue as well as being an aspect of oncofetal protein. Histol Histopathol. 2014;29:217–27. doi: 10.14670/HH-29.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hafliger P, Charles RP. The L-type amino acid transporter LAT1: an emerging target in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2428. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cormerais Y, Giuliano S, LeFloch R, Front B, Durivault J, Tambutte E, et al. Genetic disruption of the multifunctional CD98/LAT1 complex demonstrates the key role of essential amino acid transport in the control of mTORC1 and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4481–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furuya M, Horiguchi J, Nakajima H, Kanai Y, Oyama T. Correlation of L-type amino acid transporter 1 and CD98 expression with triple negative breast cancer prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:382–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi L, Luo W, Huang W, Huang S, Huang G. Downregulation of L-type amino acid transporter 1 expression inhibits the growth, migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:106–12. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hafliger P, Graff J, Rubin M, Stooss A, Dettmer MS, Altmann KH, et al. The LAT1 inhibitor JPH203 reduces growth of thyroid carcinoma in a fully immunocompetent mouse model. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:234. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0907-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen L, Qian C, Cao H, Wang Z, Luo T, Liang C. Upregulation of the solute carrier family 7 genes is indicative of poor prognosis in papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:235. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1535-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enomoto K, Sato F, Tamagawa S, Gunduz M, Onoda N, Uchino S, et al. A novel therapeutic approach for anaplastic thyroid cancer through inhibition of LAT1. Sci Rep. 2019;9:14616. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barollo S, Bertazza L, Watutantrige-Fernando S, Censi S, Cavedon E, Galuppini F, et al. Overexpression of L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) and 2 (LAT2): novel markers of neuroendocrine tumors. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun D, Wirth EK, Wohlgemuth F, Reix N, Klein MO, Gruters A, et al. Aminoaciduria, but normal thyroid hormone levels and signalling, in mice lacking the amino acid and thyroid hormone transporter Slc7a8. Biochem J. 2011;439:249–55. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verrey F, Closs EI, Wagner CA, Palacin M, Endou H, Kanai Y. CATs and HATs: the SLC7 family of amino acid transporters. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:532–42. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1086-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badziong J, Ting S, Synoracki S, Tiedje V, Brix K, Brabant G, et al. Differential regulation of monocarboxylate transporter 8 expression in thyroid cancer and hyperthyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177:243–50. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babu E, Kanai Y, Chairoungdua A, Kim DK, Iribe Y, Tangtrongsup S, et al. Identification of a novel system L amino acid transporter structurally distinct from heterodimeric amino acid transporters. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43838–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole KA, Chuaqui RF, Katz K, Pack S, Zhuang Z, Cole CE, et al. cDNA sequencing and analysis of POV1 (PB39): a novel gene up-regulated in prostate cancer. Genomics. 1998;51:282–7. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q, Bailey CG, Ng C, Tiffen J, Thoeng A, Minhas V, et al. Androgen receptor and nutrient signaling pathways coordinate the demand for increased amino acid transport during prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7525–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodoy S, Martin L, Zorzano A, Palacin M, Estevez R, Bertran J. Identification of LAT4, a novel amino acid transporter with system L activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12002–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuchs BC, Finger RE, Onan MC, Bode BP. ASCT2 silencing regulates mammalian target-of-rapamycin growth and survival signaling in human hepatoma cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C55–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00330.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanai Y, Hediger MA. The glutamate and neutral amino acid transporter family: physiological and pharmacological implications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:237–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Liu R, Shuai Y, Huang Y, Jin R, Wang X, et al. ASCT2 (SLC1A5)-dependent glutamine uptake is involved in the progression of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:82–93. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0637-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Zhao T, Li Z, Wang L, Yuan S, Sun L. The role of ASCT2 in cancer: a review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;837:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim HM, Lee YK, Koo JS. Expression of glutamine metabolism-related proteins in thyroid cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:53628–41. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pramod AB, Foster J, Carvelli L, Henry LK. SLC6 transporters: structure, function, regulation, disease association and therapeutics. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:197–219. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coothankandaswamy V, Cao S, Xu Y, Prasad PD, Singh PK, Reynolds CP, et al. Amino acid transporter SLC6A14 is a novel and effective drug target for pancreatic cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:3292–306. doi: 10.1111/bph.13616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polewski MD, Reveron-Thornton RF, Cherryholmes GA, Marinov GK, Aboody KS. SLC7A11 overexpression in glioblastoma is associated with increased cancer stem cell-like properties. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26:1236–46. doi: 10.1089/scd.2017.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takeuchi S, Wada K, Toyooka T, Shinomiya N, Shimazaki H, Nakanishi K, et al. Increased xCT expression correlates with tumor invasion and outcome in patients with glioblastomas. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:33–41. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318276b2de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vekony N, Wolf S, Boissel JP, Gnauert K, Closs EI. Human cationic amino acid transporter hCAT-3 is preferentially expressed in peripheral tissues. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12387–94. doi: 10.1021/bi011345c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El Ansari R, Craze ML, Miligy I, Diez-Rodriguez M, Nolan CC, Ellis IO, et al. The amino acid transporter SLC7A5 confers a poor prognosis in the highly proliferative breast cancer subtypes and is a key therapeutic target in luminal B tumours. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20:21. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-0946-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bik-Multanowski M, Pietrzyk JJ. LAT1 gene variants: potential factors influencing the clinical course of phenylketonuria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2006;29:684. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Espino Guarch M, Font-Llitjos M, Murillo-Cuesta S, Errasti-Murugarren E, Celaya AM, Girotto G, et al. Mutations in L-type amino acid transporter-2 support SLC7A8 as a novel gene involved in age-related hearing loss. Elife. 2018;7:e31511. doi: 10.7554/eLife.31511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ito T, Seyama T, Hayashi Y, Hayashi T, Dohi K, Mizuno T, et al. Establishment of 2 human thyroid-carcinoma cell-lines (8305c, 8505c) bearing p53 gene-mutations. Int J Oncol. 1994;4:583–6. doi: 10.3892/ijo.4.3.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L, Zhang Y, Mehta A, Boufraqech M, Davis S, Wang J, et al. Dual inhibition of HDAC and EGFR signaling with CUDC-101 induces potent suppression of tumor growth and metastasis in anaplastic thyroid cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9073–85. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Imai H, Shimizu K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, et al. Prognostic significance of L-type amino acid transporter 1 expression in resectable stage I–III nonsmall cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:742–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ichinoe M, Yanagisawa N, Mikami T, Hana K, Nakada N, Endou H, et al. L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) expression in lymph node metastasis of gastric carcinoma: its correlation with size of metastatic lesion and Ki-67 labeling. Pathol Res Pract. 2015;211:533–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Imai H, Shimizu K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, et al. Expression of L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) in neuroendocrine tumors of the lung. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:553–61. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janpipatkul K, Suksen K, Borwornpinyo S, Jearawiriyapaisarn N, Hongeng S, Piyachaturawat P, et al. Downregulation of LAT1 expression suppresses cholangiocarcinoma cell invasion and migration. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1668–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaji M, Kabir-Salmani M, Anzai N, Jin CJ, Akimoto Y, Horita A, et al. Properties of L-type amino acid transporter 1 in epidermal ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:329–36. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181d28e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McClellan WM, Schafer JA. Transport of the amino acid analog, 2-aminobicyclo(2,2,1)-heptane-2-carboxylic acid, by Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;311:462–75. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim CS, Cho SH, Chun HS, Lee SY, Endou H, Kanai Y, et al. BCH, an inhibitor of system L amino acid transporters, induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:1096–100. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oda K, Hosoda N, Endo H, Saito K, Tsujihara K, Yamamura M, et al. L-type amino acid transporter 1 inhibitors inhibit tumor cell growth. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:173–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kongpracha P, Nagamori S, Wiriyasermkul P, Tanaka Y, Kaneda K, Okuda S, et al. Structure-activity relationship of a novel series of inhibitors for cancer type transporter L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) J Pharmacol Sci. 2017;133:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okano N, Naruge D, Kawai K, Kobayashi T, Nagashima F, Endou H, et al. First-in-human phase I study of JPH203, an L-type amino acid transporter 1 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2020 Mar 20; doi: 10.1007/s10637-020-00924-3. [Epub]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Al Moudi M, Sun Z, Lenzo N. Diagnostic value of SPECT, PET and PET/CT in the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2011;7:e9. doi: 10.2349/biij.7.2.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:891–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khan N, Oriuchi N, Higuchi T, Zhang H, Endo K. PET in the follow-up of differentiated thyroid cancer. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:690–5. doi: 10.1259/bjr/31538331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim H, Na KJ, Choi JH, Ahn BC, Ahn D, Sohn JH. Feasibility of FDG-PET/CT for the initial diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:1569–76. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feine U, Lietzenmayer R, Hanke JP, Wohrle H, Muller-Schauenburg W. 18FDG whole-body PET in differentiated thyroid carcinoma: flipflop in uptake patterns of 18FDG and 131I. Nuklearmedizin. 1995;34:127–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Feine U, Lietzenmayer R, Hanke JP, Held J, Wohrle H, Muller-Schauenburg W. Fluorine-18-FDG and iodine-131-iodide uptake in thyroid cancer. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1468–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen W, Parsons M, Torigian DA, Zhuang H, Alavi A. Evaluation of thyroid FDG uptake incidentally identified on FDG-PET/CT imaging. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30:240–4. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328324b431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katayama D, Watabe T, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Naka S, Liu Y, et al. Preclinical evaluation of new PET tracer targeting L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1): F-18 NKO-035 PET in inflammation model of rats. J Nucl Med. 2018;59(Suppl 1):1121. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beheshti M, Pocher S, Vali R, Waldenberger P, Broinger G, Nader M, et al. The value of 18F-DOPA PET-CT in patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma: comparison with 18F-FDG PET-CT. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:1425–34. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giovanella L, Treglia G, Iakovou I, Mihailovic J, Verburg FA, Luster M. EANM practice guideline for PET/CT imaging in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47:61–77. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phan HT, Jager PL, Plukker JT, Wolffenbuttel BH, Dierckx RA, Links TP. Comparison of 11C-methionine PET and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET in differentiated thyroid cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2008;29:711–6. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328301835c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barth RF, Coderre JA, Vicente MG, Blue TE. Boron neutron capture therapy of cancer: current status and future prospects. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3987–4002. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Das BC, Thapa P, Karki R, Schinke C, Das S, Kambhampati S, et al. Boron chemicals in diagnosis and therapeutics. Future Med Chem. 2013;5:653–76. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Detta A, Cruickshank GS. L-amino acid transporter-1 and boronophenylalanine-based boron neutron capture therapy of human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2126–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wongthai P, Hagiwara K, Miyoshi Y, Wiriyasermkul P, Wei L, Ohgaki R, et al. Boronophenylalanine, a boron delivery agent for boron neutron capture therapy, is transported by ATB0,+, LAT1 and LAT2. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:279–86. doi: 10.1111/cas.12602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Watabe T, Ikeda H, Nagamori S, Wiriyasermkul P, Tanaka Y, Naka S, et al. 18F-FBPA as a tumor-specific probe of L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1): a comparison study with 18F-FDG and 11C-Methionine PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:321–31. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sauerwein W, Wittig A, Moss R, Nakagawa Y. Neutron capture therapy. Chapter 4. Berlin: Springer; 2012. pp. 55–68. Compact Neutron Generator for BNCT. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dagrosa MA, Viaggi M, Kreimann E, Farias S, Garavaglia R, Agote M, et al. Selective uptake of p-borophenylalanine by undifferentiated thyroid carcinoma for boron neutron capture therapy. Thyroid. 2002;12:7–12. doi: 10.1089/105072502753451904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dagrosa MA, Viaggi M, Longhino J, Calzetta O, Cabrini R, Edreira M, et al. Experimental application of boron neutron capture therapy to undifferentiated thyroid carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:1084–92. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00778-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dagrosa MA, Thomasz L, Longhino J, Perona M, Calzetta O, Blaumann H, et al. Optimization of boron neutron capture therapy for the treatment of undifferentiated thyroid cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1059–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hayashi K, Jutabha P, Endou H, Anzai N. c-Myc is crucial for the expression of LAT1 in MIA Paca-2 human pancreatic cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2012;28:862–6. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wierstra I, Alves J. The c-myc promoter: still MysterY and challenge. Adv Cancer Res. 2008;99:113–333. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(07)99004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vita M, Henriksson M. The Myc oncoprotein as a therapeutic target for human cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:318–30. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bieche I, Franc B, Vidaud D, Vidaud M, Lidereau R. Analyses of MYC, ERBB2, and CCND1 genes in benign and malignant thyroid follicular cell tumors by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Thyroid. 2001;11:147–52. doi: 10.1089/105072501300042802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sakr HI, Chute DJ, Nasr C, Sturgis CD. cMYC expression in thyroid follicular cell-derived carcinomas: a role in thyroid tumorigenesis. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12:71. doi: 10.1186/s13000-017-0661-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhu X, Enomoto K, Zhao L, Zhu YJ, Willingham MC, Meltzer P, et al. Bromodomain and extraterminal protein inhibitor JQ1 suppresses thyroid tumor growth in a mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:430–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Enomoto K, Zhu X, Park S, Zhao L, Zhu YJ, Willingham MC, et al. Targeting MYC as a therapeutic intervention for anaplastic thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:2268–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Elorza A, Soro-Arnaiz I, Melendez-Rodriguez F, Rodriguez-Vaello V, Marsboom G, de Carcer G, et al. HIF2α acts as an mTORC1 activator through the amino acid carrier SLC7A5. Mol Cell. 2012;48:681–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Onishi Y, Hiraiwa M, Kamada H, Iezaki T, Yamada T, Kaneda K, et al. Hypoxia affects Slc7a5 expression through HIF-2α in differentiated neuronal cells. FEBS Open Bio. 2019;9:241–7. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tomblin JK, Arthur S, Primerano DA, Chaudhry AR, Fan J, Denvir J, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) regulation of L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT-1) expression in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;106:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Grzes KM, Swamy M, Hukelmann JL, Emslie E, Sinclair LV, Cantrell DA. Control of amino acid transport coordinates metabolic reprogramming in T-cell malignancy. Leukemia. 2017;31:2771–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dann SG, Ryskin M, Barsotti AM, Golas J, Shi C, Miranda M, et al. Reciprocal regulation of amino acid import and epigenetic state through Lat1 and EZH2. EMBO J. 2015;34:1773–85. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]