Abstract

Background

Squama Manitis (pangolin scale) has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years. However, its efficacy has not been systematically reviewed. This review aims to fill the gap.

Methods

We searched six electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure Database (CNKI), WanFang Database and SinoMed from inception to May 1, 2020. Search terms included “pangolin”, “Squama Manitis”, “Manis crassicaudata”, “Manis javanica”, “Malayan pangolins”, “Manis pentadactyla”, “Ling Li”, “Chuan Shan Jia”, “Shan Jia”, “Pao Jia Zhu”, “Jia Pian” and “Pao Shan Jia”. The Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment tool and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) were used to evaluate the risk of bias of the included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and case control studies (CCSs).

Results

After screening, 15 articles that met the inclusion criteria were finally included. There were 4 randomized controlled trials, 1 case control study, 3 case series and 7 case reports. A total of 15 different diseases were reported in these studies, thus the data could not be merged to generate powerful results. Two RCTs suggested that Squama Manitis combined with herbal decoction or antibiotics could bring additional benifit for treating postpartum hypogalactia and mesenteric lymphadenitis. However, this result was not reliable due to low methodological quality and irrational outcomes. The other two RCTs generated negative results. All the non-RCTs did not add any valuable evidence to the efficacy of Squama Manitis beacause of small samples, incomplete records, non-standardized outcome detection. In general, currently available evidence cannot support the clinical use of Squama Manitis.

Conclusion

There is no reliable evidence that Squama Manitis has special medicinal value. The removal of Squama Manitis from Pharmacopoeia is rational.

Keywords: Pangolin, Squama Manitis, Coronavirus disease 2019, Clinical efficacy, Systematic review

1. Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has become a global pandemic.1 Its origin remains unclear. Several studies suggested that bats might be the natural host for SARS-CoV-2,2, 3 while snakes and pangolins were potential intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to humans.4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Various types of virus hosted in wild animals can threaten human health and safety. The Squama Manitis (pangolin scale) is a medicinal material in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), commonly used to promote lactation in women and reduce swelling.9 Due to the exaggeration of its medicinal value, pangolins were facing extinction caused by excessive killing.10 In 2019, pangolin has been listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of threatened species. In order to enhance the protection of pangolin, China officially proclaimed pangolin to be a national level protected wildlife animal on June 3, 2020.11 In Chinese Pharmacopoeia(2020 edition), Squama Manitis has been removed.

Till now, the clinical value of Squama Manitis has not been well assessed. Whether Squama Manitis has special clinical effect? Whether researchers need to find substitutes? Answers to these questions should be based on clinical evidence. This review aimed to summarize all the clinical studies to generate reliable evidence for decision-making on the medicinal value of Squama Manitis.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

We developed a comprehensive literature search by electronic literature databases including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure Database (CNKI), WanFang Database and SinoMed from inception to May 1, 2020. “Pangolin”, “Squama Manitis”, “Manis crassicaudata”, “Manis javanica”, “Malayan pangolins”, “Manis pentadactyla”, “Ling Li”, “Chuan Shan Jia”, “Shan Jia”, “Pao Jia Zhu”, “Jia Pian” and “Pao Shan Jia” were used as key words in different databases. The search strategy in PubMed is presented in supplement 1 and the search strategy in CNKI is presented in supplement 2.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

We included all types of clinical studies in this review, consisting of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), case control studies (CCSs), case series and case reports. No restriction was applied on age, gender or ethnicity. For controlled studies, trials that applied Squama Manitis at any dosage for the intervention groups were included, either alone or in combination with herbal or western medicine. Routine treatment used in both intervention and control groups were the same. As for case series and case reports, we only included studies which used Squama Manitis alone. There were no restrictions on the outcomes of included studies.

2.3. Data selection and data extraction

Two reviewers (KW, NL) screened all included studies by titles and abstracts according to the eligibility criteria. Any disagreement in the study selection was resolved by consulting a third reviewer (WZ). Eligible studies were reviewed by two researchers (KW, NL) and data was extracted independently. Data was extracted using a pre-designed excel sheet including authors, years of publication, interventions, diseases and outcomes. After cross-check, any inconformity in data extraction was resolved by discussing or consulting with a third researcher (WZ).

2.4. Assessment of risk of bias

The quality of RCTs was assessed by Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment tool,12 which included six aspects: (1) Random sequence generation, (2) Allocation concealment, (3) Blinding of participants and personnel, (4) Incomplete outcome data, (5) Selective reporting, (6) Other bias. The assessment results were presented as “low risk”, “high risk” or “unclear risk”. The quality of CCSs was assessed by Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).13 The NOS contained three components with eight questions: (1) selection of the groups of the study, (2) comparability, (3) assessment of the outcome. A scoring system of 9 points was used to assess the quality of CCSs; higher score means better quality. Two researchers carried out the quality assessment independently. Disagreement was resolved after consensus or consulting a third researcher.

2.5. Data analysis

Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3 was used to perform statistical analysis. Risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was adopted for dichotomous outcomes. Mean difference (MD) with a 95% CI was used for continuous outcomes. Cochrane's Q and I2 were used to explore the heterogeneity among studies. Due to different diseases, interventions and outcomes reported in the included studies, no meta-analysis was performed to merge data.

3. Results

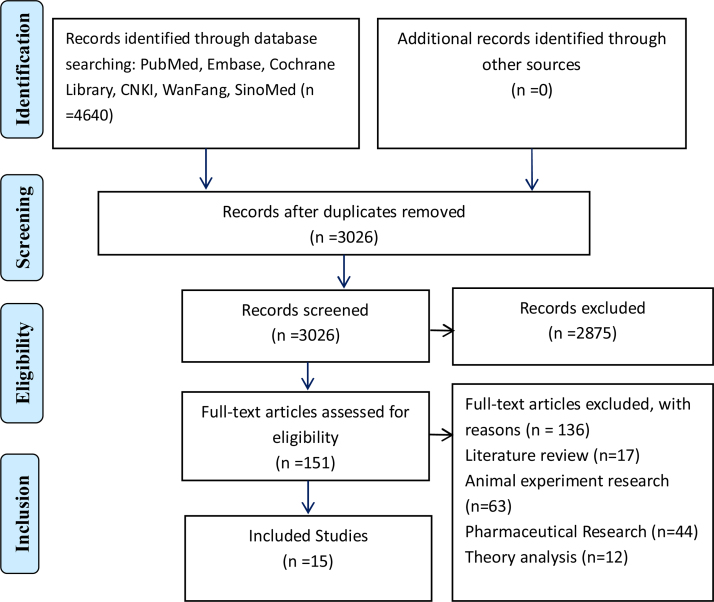

A total of 4640 records were identified as potentially eligible for inclusion. After excluding duplicates, 3026 studies were screened by their titles and abstracts. According to the eligibility criteria, 151 articles were preliminarily selected for further assessment and 136 of them were excluded, which were review articles, animal experiments, pharmaceutical researches and theory analysis. Finally, 15 articles were included for analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and trials selection.

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

Types of the 15 included studies14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 were 4 RCTs,14, 15, 16, 17 1 CCS,18 3 case series19, 20, 21 and 7 case reports.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 These studies were published from 1989 to 2018, with 80% of them published 10 years ago. Fifteen studies covered 15 types of diseases, including postpartum hypogalactia, breast hyperplasia, acute mastitis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, leukopenia, prostatic hyperplasia, paronychia, hyperlipidemia, chronic leg ulcer, periarteritis nodosa, verruca plana, neurodermatitis, parkinsonian disorders, glomerulonephritis, periarthritis of the shoulder. Details of RCTs and non-RCTs were shown in Table 1 and Table 2 respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included RCTs.

| First author (Year) [ref] | Study type | Sample size (T/C) | Disease | Intervention | Control | Course of treatment | Follow-up | Outcome | Results RR, 95% CI, P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liang (2018)14 | RCTs | 243 (123/120) | Postpartum hypogalactia | Squama Manitis powder + C | herbal decoction | Not reported | Not reported | Efficacy rate | 1.21 (1.11,1.32), P < 0.00001 |

| Jiang (2007)15 | RCTs | 100(50/50) | Breast hyperplasia | Squama Manitis powder + C | Herbal decoction | Not reported | Not reported | Efficacy rate | 1.07 (0.96,1.19), P = 0.24 |

| Zhang (2011)16 | RCTs | 96 (48/48) | Acute mastitis | Squama Manitis powder + C | Cefuroxime Sodium for Injection | 5 days | Not reported | Efficacy rate | 1.13 (0.95,1.35), P = 0.16 |

| Zhu (2013)17 | RCTs | 86 (43/43) | Mesenteric lymphadenitis | Squama Manitis powder + C | Ceftriaxone Sodium for Injection | 10 days | 30 days | Efficacy rate | 1.51 (1.09,2.09), P = 0.01 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included non-RCTs.

| First author (year) [ref] | Study type | Sample size (T/C) conditions | Disease | Intervention | Control | Treatment follow-up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang (1994)18 | CCSs | 53(13/40) | Leukopenia | Squama Manitis powder | Leucogen Tablets, Tabellae Batiloli | 30-60 days not reported | Leucocyte count Treatment group: 5 × 109/L–6 × 109/L Control: (4-5) × 109/L–5 × 109/L |

| Zhang (1997)19 | Case series | 42 | Prostatic hyperplasia | Squama Manitis powder | None | 14-28 days 6 months to 4 years |

Efficacy rate: 95% |

| Li (2004)20 | Case series | 100 | Paronychia | Squama Manitis powder (topical usage) + Conventional disinfection | None | 7 days not reported | Efficacy rate: 100% |

| Fan (2002)21 | Case series | 62 | Hyperlipidemia | Squama Manitis powder | None | 60 days not reported | Efficacy rate lowering cholesterol: 74%; lowering triglyceride: 65.5% |

| Qian (1989)22 | Case report | 5 | Chronic leg ulcer | Squama Manitis powder (topical usage) | None | 12 days not reported | The ulcer healed without scars or pigmentation |

| Li (1991)23 | Case report | 1 | Periarteritis nodosa | Squama Manitis powder | None | 31 days 5 years |

Swelling and pain in periartheritis nodosa relieved, nodules disappeared and the disease recovery |

| Wu (2000)24 | Case report | 1 | Verruca plana | Squama Manitis powder | None | 5 days 20 days |

Verruca plana healed without scarring |

| Pan (2001)25 | Case report | 1 | Neurodermatitis | Squama Manitis Quicklime Water Infusion (topical usage) | None | 4 days 30 days |

The itching disappeared and the skin returned to normal after 1 month |

| Jin (2002)26 | Case report | 1 | Parkinsonian disorders | Squama Manitis powder | None | 90 days 2 years |

After 3 months, the tremors of the upper and lower lips stopped, and there was no recurrence after 2 years of follow-up |

| Tian (2002)27 | Case report | 1 | Glomerulonephritis | Squama Manitis powder | None | 6 days not reported |

Urine colour was light yellow after 1 week and routine urine test result returned to normal |

| Ren (2005)28 | Case report | 1 | Periarthritis of the shoulder | Squama Manitis powder | None | 30 days 3 years |

Shoulder pain were significantly alleviated after 1 week, and healed after 1 month without recurrence for 3 years |

3.2. Risk of bias

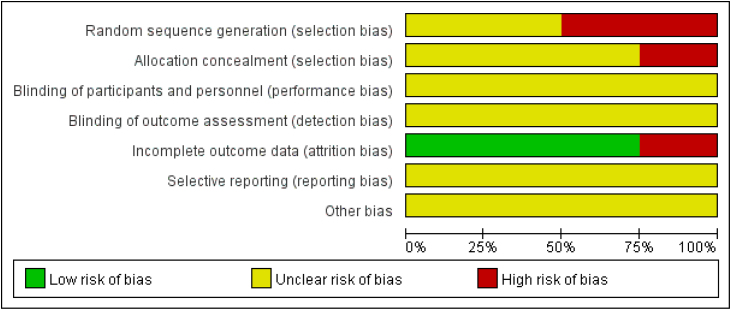

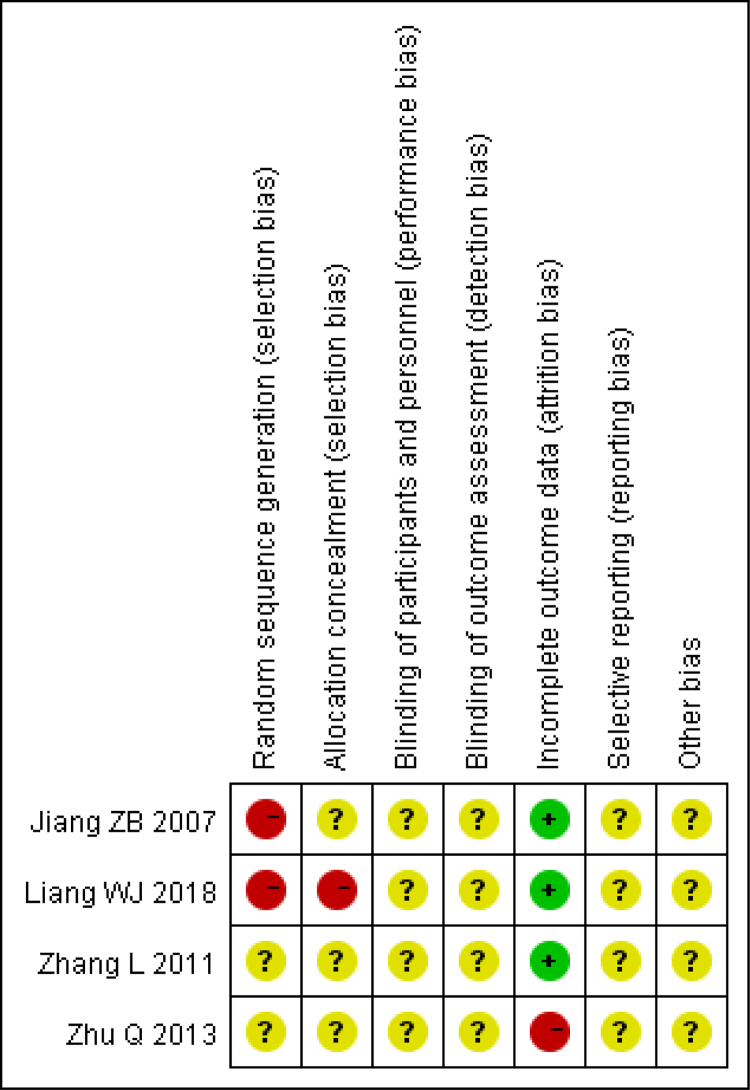

The risk of bias assessment on each included RCT was presented in Fig. 2, Fig. 3. Among the included RCTs, two were assessed with a high risk of selection bias due to their incorrect utilization of randomization methods.14, 15 The other two RCTs did not clearly report how to generate random sequence. One RCT of Squama Manitis in the treatment of postpartum hypogalactia was assessed with a high risk of selection bias due to its incorrect usage of allocation concealment methods14 and the remaining RCTs had unclear allocation concealment. There was also a lack of clear report in blinding of participants and personnel and blinding of outcomes assessment, resulting in an unclear assessment for performance and detection bias. High attrition bias was assessed for one RCT using Squama Manitis in the treatment of mesenteric lymphadenitis in children, with a loss of 4 patients in the control group during follow up.17 The other 3 RCTs were assessed with a low risk of attribution bias. Reporting bias for all included RCTs was assessed unclear due to the lack of pre-registered study protocols.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias graph.

Fig. 3.

Risk of bias summary. +: low risk of bias; −: high risk of bias; ?: unclear risk of bias.

One CCS's quality was assessed by NOS.18 Though the study reported the selection of controls (both groups of patients were from the same hospital and the same department), the rest items of NOS were lack of clarity, hence the study was scored as 1 point.

3.3. Clinical efficacy

The results of the 4 RCTs were described as follows. Liang (2018) tested the efficacy rate of Squama Manitis for treating postpartum hypogalactia.14 They randomly allocated 243 patients treated with either Squama Manitis powder combined with herbal decoction (n = 123) or herbal decoction alone (n = 120). The results showed that Squama Manitis powder combined with herbal decoction has a higher efficacy rate than using herbal decoction alone (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.11–1.32, P < 0.00001).

Jiang (2007) tested the efficacy rate of Squama Manitis for treating breast hyperplasia.15 They randomly allocated 100 patients into Squama Manitis powder combined with herbal decoction (n = 50) and herbal decoction (n = 50). The result showed no statistical difference in efficacy rate between the two groups (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.96–1.19, P = 0.24).

Zhang (2011) tested the efficacy rate of Squama Manitis for treating acute mastitis.16 They randomly allocated 96 patients into Squama Manitis powder combined with Cefuroxime Sodium for Injection (n = 48) and Cefuroxime Sodium for Injection (n = 48). The result was inconclusive because there was no statistical significant difference between the two groups (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.95–1.35, P = 0.16).

Zhu (2013) tested the efficacy rate of Squama Manitis for treating mesenteric lymphadenitis.17 They randomly allocated 86 patients into Squama Manitis powder combined with Ceftriaxone Sodium for Injection (n = 43) and Ceftriaxone Sodium for Injection (n = 43). The result showed that the effect of Squama Manitis powder combined with Ceftriaxone Sodium for Injection was better than Ceftriaxone Sodium for Injection alone (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.09–2.09, P = 0.01).

The CCS recruited 13 patients in Squama Manitis group and 40 patients in control group.18 Number of leukocytes in both groups before and after treatment were reported. The total number of leukocytes in the treatment group was maintained at about 6 × 109/L, and that in the control group was maintained at 5 × 109/L.

There were 3 case series19, 20, 21 about prostatic hyperplasia, paronychia and, hyperlipidemia, with the sample size of 42, 100 and 62 respectively. According to the results, the effeicacy rate of Squama Manitis powder for prostatic hyperplasia was 95%.19 Squama Manitis powder (topical usage) combined with conventional disinfection had 100% efficacy rate for treating paronychia.20 The efficacy rate of Squama Manitis powder were 74% and 65.5% respectively for lowering cholesterol and triglyceride.21

There were 7 case reports,14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 which covered diseases of chronic leg ulcer, periarteritis nodosa, verruca plana, neurodermatitis, parkinsonian disorders, glomerulonephritis and periarthritis of the shoulder. The results of these case reports showed that Squama Manitis had effect on above diseases. However, these case reports and case series could not provide any relaible evidence for the efficacy of Squama Manitis.

4. Discussion

This review evaluated the current clinical evidence of Squama Manitis. There were 4 RCTs, 1 CCS, 3 case series and 7 case reports included in this review. The results of RCTs suggested that Squama Manitis combined with herbal decoction or antibiotics could bring additional benifit for treating postpartum hypogalactia and mesenteric lymphadenitis. While for breast hyperplasia and acute mastitis, the results were inconclusive. Results from non-RCTs showed that Squama Manitis might be effective in treating leukopenia, prostatic hyperplasia, paronychia, hyperlipidemia, chronic leg ulcer, periarteritis nodosa, verruca plana, neurodermatitis, parkinsonian disorders, glomerulonephritis and periarthritis of the shoulder. Most of the diseases mentioned above have conventional effective treatments. It is deemed unnecessary to use Squama Manitis.

Further more, results from above studies should be interpreted with caution due to low methodological quality which would lead to significant biases. The 4 RCTs included in this review have small sample sizes, and focused on different diseases. As a consequence, no meta-analysis was performed to generate powerful results. Moreover, there was a lack of rational and valuable outcome measures in the included studies. And the reporting quality of included case reports was low due to the incompleteness in the records of diagnosis and treatment and unstandardization in the outcomes measurement for efficacy. Furthermore, case reports without control could not test the efficacy of Squama Manitis. In general, all the non-RCTs did not add any valuable evidence to the efficacy of Squama Manitis.

There were also several limitations in this review. A protocol was not registered or published before conducting this systematic review. Although a comprehensive literature search was performed in commonly used databases, there was also potential omission of grey literatures due to the lack of alternative search methods. Clinical studies using Squama Manitis or combined with other drugs were reviewed, while clinical studies using TCM prescriptions containing Squama Manitis were not included in this review. Hence, it was impossible to evaluate the efficacy of Squama Manitis in TCM prescriptions in this review.

Based on above data-analyse, there was no reliable evidence for the clinical value of Squama Manitis. Furthermore, there might be a risk of experiencing anaphylaxis in the consumption of Squama Manitis. Several studies reported that the use of Squama Manitis might trigger allergic reactions such as dizziness, chills, shortness of breath, sweating, pruritus, skin redness and rashes.29, 30, 31 Pangolin is one kind of wildlife on the verge of extinction. There is no reason to use Squama Manitis in clinical practice.

Wild pangolins may carry pathogens that can cause infections in human beings.6 Hence, it is highly recommended to restrict the use of Squama Manitis as medicine or food in order to protect endangered wildlife species and human safety.32 In the recent edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, Squama Manitis has been removed out.

There are still several Chinese patent medicines containing Squama Manitis listed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2015 edition), such as compound Tongbi capsule, Guilingji, Huixiangjuhe pill, Kangsuan (antithrombotic) Zaizao pill, Tongru granule and Jinpu capsule being used clinically. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out studies on substitutes for these medicines. Several studies have shown that there are similarities in the composition of pig's hoof nails and Squama Manitis in regards to the trace elements and inorganic contents through thin layer, column and spectrum chromatography analysis.33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

In conclusion, there is no reliable evidence for the clinical value of Squama Manitis. It is rational to prohibit the use of Squama Manitis for treatment or healthcare purpose.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: JZ. Methodology: WP and FY. Software: NL, YL and XJ. Validation: WZ and JZ. Formal analysis: XJ and KW. Investigation: WP and NL. Data curation: KW, NL and WZ. Writing – original draft: XJ and HZC. Writing – review and editing: JZ, WZ, FY and BP. Supervision: JZ. Project administration: XJ and HZC. Funding acquisition: JZ.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there was no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by Innovation Team Cultivation Program of Tianjin Higher Education Institutions – Chinese Medicine Clinical Evaluation Methods (TD13-5407).

Ethical statement

This study is based on published literature and does not require informed consent and ethics approval.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study will be made available on request.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.imr.2020.100486.

Contributor Information

Wenke Zheng, Email: zhengwk@tice.com.cn.

Junhua Zhang, Email: zjhtcm@foxmail.com.

Supplementary material

The following are supplementary material to this article:

References

- 1.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N., Zhang D.Y., Wang W.L., Li X.W., Yang B., Song J.D. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang W., Si H.R. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji W., Wang W., Zhao X.F., Zai J.J., Li X.G. Cross-species transmission of the newly identified coronavirus 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol. 2020;92:433–440. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z.X., Xiao X., Wei X.L., Li J., Yang J., Tan H.B. Composition and divergence of coronavirus spike proteins and host ACE2 receptors predict potential intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-2. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25726. [published online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu P., Chen W., Chen J.P. Viral metagenomics revealed sendai virus and coronavirus infection of Malayan Pangolins (Manitis javanica) Viruses. 2019;11:979. doi: 10.3390/v11110979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang T., Wu Q., Zhang Z. Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak [published correction appears in Curr Biol. 2020 Apr 20;30(8):1578] Curr Biol. 2020;30 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.063. 1346-1351.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam T.T., Jia N., Zhang Y.W., Shum M.H., Jiang J.F., Zhu H.C. Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. [published online ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission . One, China Medical Science Press; Beijing: 2015. Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo S.S., Peng J.J., Liu S., Liu P. An overview of Wild Pangolins Status and the related illicit trade in China. J Chongqing Norm Univ (Nat Sci) 2019;36:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.State Forestry and Grassland Bureau . 2020. The pangolin is promoted to the national first-level protected wildlife [EB/OL] Available from: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/main/72/20200608/093808350793059.html [accessed June 9] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins J., Green S.R. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. Cochrane handbook for systematic review of interventions. Version 5.1.0. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells G., Shea B., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M. 2020. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp [accessed April 30] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang W.J. The effect of Squama Manitis free decoction granules on low postpartum milk. Electron J Clin Med Lit. 2018;5:71. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Z.B., Guo J.B., Zhou Y.P. The effects of different doses of Squam Manitis and different oral methods on hyperplasia of the breast. J Sichuan Trad Chin Med. 2007:37–38. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L. The clinical efficacy of Squam Manitis powder combined with antibiotics in the treatment of acute mastitis. Zhejiang J Integr Trad Chin West Med. 2011;21:269. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Q., Li M.J., Zhou G.L. The clinical effect of Squam Manitis powder on mesenteric lymphadenitis in children. Chin J Trad Med Sci Technol. 2013;20:412–413. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang C.Q., Zhu R.H., Guo Z.W. An observational study on Squama Manitis treatment of leukopenia. J Navy Med. 1994:135. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y.J., Wang D., Zhang H.Q., Dou Q.F., Yuan J.Y. The Squama Manitis is used to treat 42 patients with prostatic hyperplasia. Chin J Integr Trad West Med. 1997:627. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S.J., Xu L.S. 100 cases of paronychia were treated with topical Squama Manitis. Chin Commun Doctors. 2004:39. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan X.F. Squama Manitis is used to treat chest paralysis and hyperlipidemia. J Tradit Chin Med. 2002:252. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian H.X. Topical application of Squama Manitis powder to treat leg ulcers. Shandong J Trad Chin Med. 1989:51. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H.S. Squama Manitis treatment for periarteritis nodosa. J New Chin Med. 1991:20. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu K.Z. Squama Manitis powder for treating verruca plana. Chin Naturopath. 2000:46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan N.S., Pei J. Squama Manitis treatment of neurodermatitis. Pract New Med. 2001;003:253. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin D.Q. Squama Manitis powder is taken orally for Parkinsonia disorders. J Tradit Chin Med. 2002:252. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian X.Y., Tian X.S. Squama Manitis treat hematuria. J Tradit Chin Med. 2002:254. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren L.B., Zhou H. Squama Manitis has good effect in the treatment of periarthritis of the shoulder. Nei Mongol J Trad Chin Med. 2005:7. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Z.D., Zhao Y. One case of allergy caused by oral Squam Manitis. Chin J Integr Med Cardio-Cerebrovasc Dis. 1993:58. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z.X. One case of allergic reaction caused by taking Squam Manitis. Chin J Hosp Pharm. 1993:36. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhuang H.C. A case of rash caused by Squam Manitis. J Pract Trad Chin Med. 1999:48. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Volpato G., Fontefrancesco M.F., Gruppuso P., Zocchi D.M., Pieroni A. Baby pangolins on my plate: possible lessons to learn from the COVID-19 pandemic. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2020;16:19. doi: 10.1186/s13002-020-00366-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tian S.X., Li L.H., Li S.M., Zhu C.F., Wang X.G., Li C.X. Comparative analysis of amino acid content between Squam Manitis and pig toenails. J Hebei Trad Chin Med Pharmacol. 2000;15:28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo X.T., Qian J., Li Y. Analysis and comparison of chemical elements and amino acids in pig toenails and Squam Manitis. Chin Arch Trad Chin Med. 2002;20:604–605. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo J., Yan D., Zhang D., Feng X., Yan Y., Dong X. Substitutes for endangered medicinal animal horns and shells exposed by antithrombotic and anticoagulation effects. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao Y., Fan Z.L. Study on the ingredients of Squam Manitis and pig toenails. J Chin Med Mater. 1989;12:34–37. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen H., Gu G.M., Xu Y.Q. A comparative study on the chemical composition of Squam Manitis and pig toenails. Lishizhen Med Materia Medica Res. 2009;20:2058–2060. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan Y.M., Liu G.J., Sun G.J. A comparative experiment on the thin layer analysis of pig nail and pangolin. World Latest Med Inform. 2017;17:30–31. 42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study will be made available on request.