COVID-19 Radiology Testing

Introduction

As discussed in the SARS and MERS sections of this article, early radiographic studies with regular follow up evaluations, including CT scans is important in helping to characterize and quantify the magnitude of illness, as well as monitor progression, which can be rapid in the highly pathogenic coronaviruses, especially COVID-19, as experience worldwide will attest.1, 2, 3, 4

In the earlier stages of COVID-19, as with other highly pathogenic coronaviruses that cause a severe acute respiratory syndrome, chest XRays often reveal various stages of pneumonia.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 In advancing disease clinical features consistent with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and acute cardiac injury may be present.1 , 3, 4, 5 Such patients should rapidly receive a CT scan of the chest, which often reveals various forms of ground glass opacity (GGO). In some cases there are multiple GGO located in sub-pleural regions of bilateral lungs. These likely influence the immune response, which may lead to significant pulmonary inflammation.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

In early work of Hosseiny et al., the diagnosis of COVID-19 is suspected on the basis of symptoms of pneumonia (e.g., dry cough, fatigue, myalgia, fever, and dyspnea) as well as history of recent travel or exposure to a diagnosed positive COVID-19 patient.1 [See CDC Testing Section on Case Definition and Diagnosis].

Chest imaging plays an important role in both assessment of disease extent and follow-up. Chest radiography typically shows patchy or diffuse asymmetric airspace opacities, similar to other causes of coronavirus pneumonias.8 Consistent with various early reports, Hosseiny note the first report of patients with COVID-19 described having bilateral lung involvement on initial chest CT in 40 of 41 patients, with a consolidative pattern seen in patients in the ICU and a predominantly ground-glass pattern in patients who were not in the ICU.1 , 6

The highly pathogenic coronaviruses SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 share several clinical and radiographic similarities (Table 1 ) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ), with some notable exceptions.1, 2, 3 , 7 The propensity for COVID-19 to involve both lungs more often and earlier in the illness is increasingly well documented.1 Of note, aggressive testing – radiographic and other modalities, should be utilized early with moderately to severely ill COVID-19 patients owing to significant extrapulmonary illness.1, 2, 3, 4

Table 1.

Comparison of Clinical and Radiologic Features of SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 From Hosseiny, et al (1)

| Feature | SARS | MERS | COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL SIGNS OR SYMPTOMS | |||

| Fever or chills | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dyspnea | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Malaise | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Myalgia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Headache | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cough | Dry | Dry or productive | Dry (productive w/progressive illness) |

| Diarrhea | Yes | Yes | +/- |

| Nausea or vomiting | Yes | Yes | Less common |

| Sore throat | Yes | Uncommon | Less common/but possible |

| Arthralgia | Yes | Uncommon | Less common/but possible |

| IMAGING FINDINGS | |||

| Acute phase of illness | SARS | MERS | COVID-19 |

| Initial imaging | |||

| Normal | 15–20% of patients | 17% of patients | 15–20% of patients |

| Abnormalities | |||

| Common | Peripheral multifocal airspace opacities (GGO, consolidation, or both) on chest XRay and CT scans | Diffuse findings similar to SARS | Diffuse findings similar to SARS and MERS; may be more diffuse early, or more rapidly progressive. B/L lung involvement to be expected |

| Rare | Pneumothorax | Pneumothorax | Pneumothorax |

| Not seen | Cavitation, lymphadenopathy | Cavitation, lymphadenopathy | Cavitation, lymphadenopathy |

| Appearance | Unilateral, focal (50%); Multifocal (40%); diffuse (10%) Bilateral, multifocal | Bilateral, multifocal basal airspace on CXR or CT (80%), isolated unilateral (20%) | Bilateral, multifocal, as well as basal airspace are common findings. Of note, a </=15% may present with normal CXR |

| Follow-up imaging appearance | Unilateral, focal (25%); Progressive (most common, can be unilateral and multi-focal or bilateral with multi-focal consolidation) | Extensive into upper lobes or perihilar areas, pleural effusion (33%), interlobular septal thickening (26%). | Persistent or progressive pleural airspace opacities |

| Indications of poor prognosis | Bilateral (like ARDS), four or more lung zones, progressive involvement after 12 d | Greater involvement of the lungs, pleural effusion, pneumothorax | Consolidation vs ground glass opacities (GGO) |

| SARS | MERS | COVID-19 | |

| Chronic phase of illness | Data still being reviewed | ||

| Transient reticular opacities (e) | Yes | Yes | |

| Air trapping | Common (usually persistent) | ||

| Fibrosis | Rare | One-third of patients | Data still being reviewed |

Acronyms: GGO = ground-glass opacity, ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome. aOver a period of weeks or months.

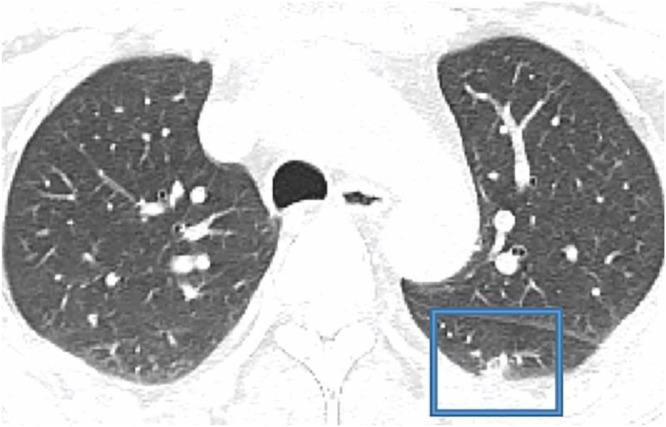

Fig. 1.

9 a CT study obtain from a 27 yo MERS patient. Notice the Lower lung image reveals largeright lower lobe and small focal left lower lobe subpleural consolidations.

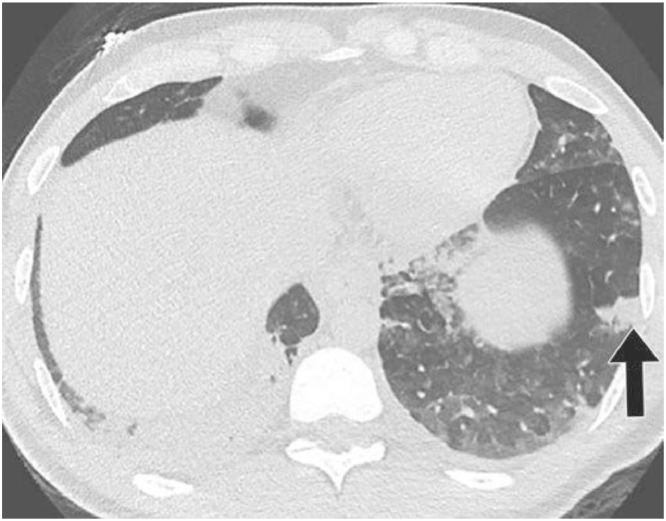

Fig. 2.

1 (Courtesy of Song F, Shanghai Public Health Clinical CenteShanghai, China) From a 79 yo COVID-19 patient.Notice bilateral multiple, patchy, and peripheral ground glass opacities (GGO).

Consider in Fig. 1 9 a CT study obtain from a 27 yo MERS patient. Notice the Lower lung image reveals large right lower lobe and small focal left lower lobe subpleural consolidations. Fig. 2 1 is from a 79 yo COVID-19 patient. Notice bilateral multiple, patchy, and peripheral ground glass opacities (GGO)

A study reviewing the initial chest CT findings in 21 individuals with confirmed COVID-19 revealed abnormal findings in 86% of patients, with a majority (16/18) showing bilateral lung involvement.7 Multifocal ground-glass opacities (GGO) (57%) and consolidation (29%) were also reported. Of note there was a tendency towards peripheral lung involvement (Figs. 2 and 3 ).1

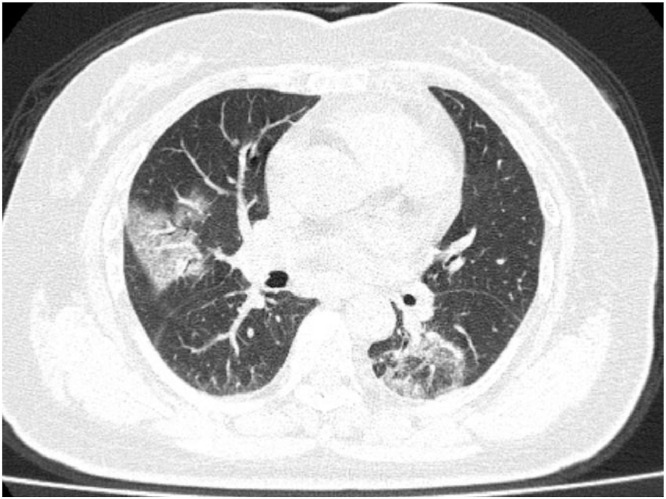

Fig. 3.

1 - 79-year-old woman Axial (A) CT Image showing multiple patchy, peripheral, bilateral areas of ground-glass opacity (Courtesy of Song F, Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, Shanghai, China).

In another study, chest imaging was obtained from a family cluster of seven persons with testing confirmed COVID-19; their studies showed bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities. There was greater involvement of the lungs reported among older family members.1 , 10

As noted earlier, although imaging features of COVID-19 resemble those of MERS and SARS,1, 2, 3, 4 it is important to recognize involvement of both lungs on initial imaging is more likely to be seen with COVID-19 (Figs. 3 and 4 ).1 By comparison, initial chest imaging abnormalities in SARS and MERS more often are unilateral (Table 1).1, 2, 3

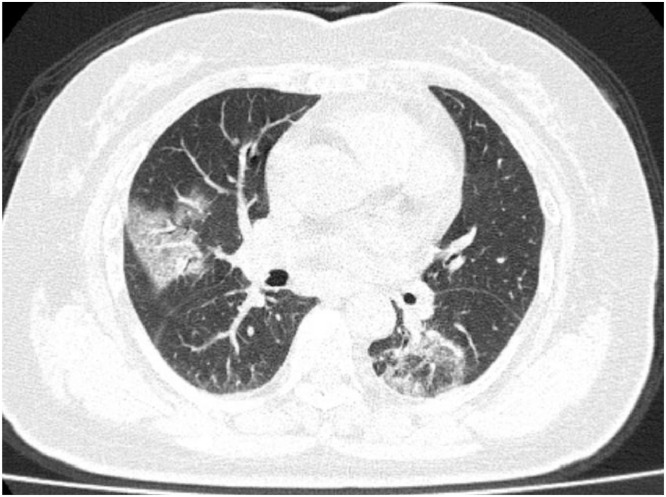

Fig. 4.

1 CT image (Courtesy of Song F, Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, Shanghai, China) Multiple patchy, peripheral, bilateral areas of ground-glass opacity.

Figs. 3 and 4 are from a 79 yo female who presented with fever, dry cough, and chest pain for 3 days. Her husband and daughter-in-law had been recently diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The patient experienced progressive illness, and expired 11 days after admission.1

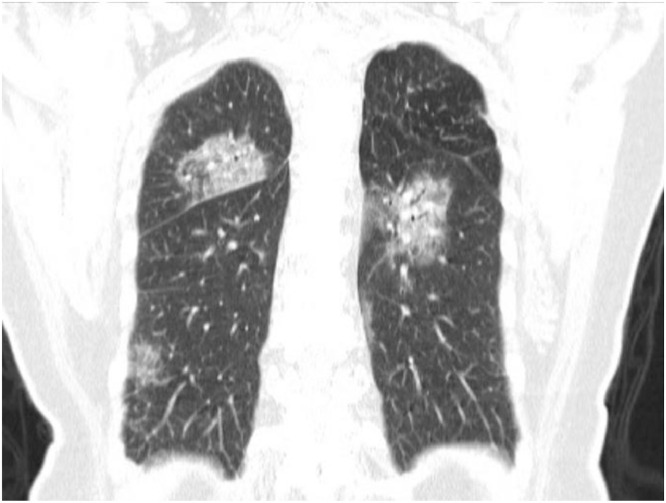

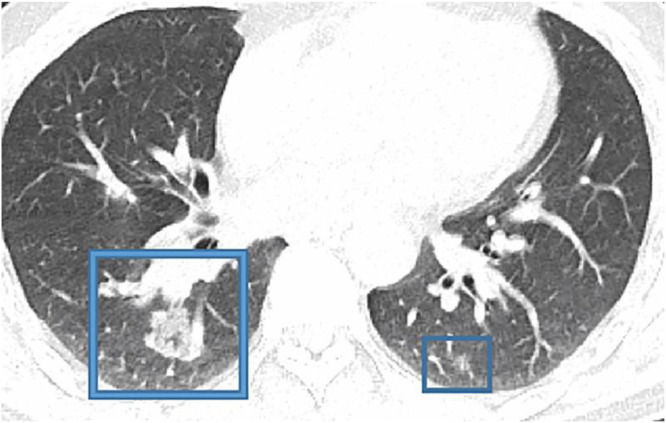

The next CT scans (Fig. 5, Fig. 6 ) were obtained from a 47 yo man with 2-day history of fever, chills, productive cough, sneezing, and fatigue who presented to the emergency department, and was ultimately diagnosed with COVID-19.1

Fig. 5.

1 47-year-old COVID-19 patient. Initial CT images obtained show small round areas of mixed ground-glass opacity and consolidation (rectangles) at level of aortic arch (A) and ventricles (B) in right and left lower lobe posterior zones. (Courtesy of Liu M, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, China).

Fig. 6.

1 Initial CT images obtained show small round areas of mixed ground-glass opacity and consolidation (rectangles) at level of aortic arch (A) and ventricles (B) in right and left lower lobe posterior zones. (Courtesy of Liu M, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, China).

As noted in the above CT scans, COVID-19 can cause early and significant pulmonary findings on chest CT, which may progress rapidly. The severity of which may portend early or greater extrapulmonary involvement. The astute clinician will anticipate the potential for rapid clinical deterioration, especially in higher risk populations, as described earlier (including advancing age, frailty, immunosuppressed state – from disease or pharmacotherapy, cardiac and other comorbidities) and manage the patient accordingly. It is worth repeating that individuals considered lower risk have also experienced rapid deterioration, and death, such that the use of risk stratification while important in accelerating management, should be used with the caveat we cannot let our guard down for any patient, as COVID-19 demonstrates an ability to cause rapidly progressive illness even among younger and seemingly more robust adult patients.

References

- 1.Hosseiny M., Kooraki S., Gholamrezanezhad A., Reddy S., Myers L, Hosseiny M., et al. Radiology perspective of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): lessons from Severe acute respiratory syndrome and middle east respiratory syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020 May;214(5):1078–1082. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22969. https://www.ajronline.org/doi/full/10.2214/AJR.20.22969 Last accessed 06/14/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Zumla A., Memish Z.A. Coronaviruses: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in travelers. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27:411–417. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das K.M., Lee E.Y., Langer R.D., Larsson S.G. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: what does a radiologist need to know. AJR. 2016;206:1193–1201. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ketai L., Paul N.S., Wong K.T. Radiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): the emerging pathologic-radiologic correlates of an emerging disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2006;21:276–283. doi: 10.1097/01.rti.0000213581.14225.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng V.C., Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Yuen K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an agent of emerging and reemerging infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:660–694. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00023-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung M., Bernheim A., Mei X., et al. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020 Feb 4 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajlan A.M., Ahyad R.A., Jamjoom L.G., Alharthy A., Maddani T.A. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection: chest CT Findings AJR. 2014;203:782–787. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.H., et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]