Abstract

Patient: Male, 36-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Explosive pleuritis

Symptoms: Abdominal pain

Medication:—

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Critical Care Medicine • Infectious Diseases • General and Internal Medicine • Nephrology • Pulmonology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

The management of patients with end-stage kidney disease can be accomplished with hemodialysis via a surgically created arteriovenous fistula. An arteriovenous fistula has an advantage because of the ability to serve as permanent access for hemodialysis over several months to years; however, it has a disadvantage because of its associated vascular and infectious complications. An infectious complication such as explosive pleuritis, which is usually due to respiratory infections, in the setting of an infected arteriovenous fistula site infection, is extremely rare.

Case Report:

A 36-year-old man with a past medical history of IgA nephropathy on hemodialysis with a left forearm arteriovenous fistula presented to the Emergency Department because of left flank pain. Despite no recent history or evidence of a respiratory tract infection, he developed explosive pleuritis within 48 h. The presence of Group A Streptococcus at the arteriovenous fistula site coincided with Streptococcus pyogenes infection. The pleural ef-fusion was drained and he was treated with antibiotics. He recovered and was eventually discharged home.

Conclusions:

Explosive pleuritis, although less frequent, is almost always secondary to respiratory tract infections. An arteriovenous fistula site infection may be the source of infection of an internal organ if no apparent source is identified.

MeSH Keywords: Arteriovenous Fistula, Empyema, Pleural Effusion, Pleurisy, Streptococcus pyogenes

Background

Certain diseases cause irreversible damage to the kidneys, and the affected patients can become dialysis-dependent. Hemodialysis can be accomplished by surgically creating an arteriovenous fistula (AVF) in the arm. Infectious and noninfectious complications are more prevalent in patients with hemo-dialysis catheters and grafts than in patients with AVFs [1–4]. For this reason, an AVF is preferred for hemodialysis [1–4]. Nonetheless, an AVF is still prone to noninfectious and infectious problems. Noninfectious complications, which are usually vascular, include ischemic steal syndrome, ischemic monomelic neuropathy, stenosis, thrombosis, fistula hemorrhage, venous hypertension, aneurysms, and pseudoaneurysms [3,5,6]. Infectious complications are secondary to common bacteria like Staphylococcus and Streptococcus [2,5]. Despite evidence to support the bacterial complications, the spread of an AVF infection to other organs is still uncommon.

Our patient developed explosive pleuritis, with the AVF as the likely source of infection. Explosive pleuritis has been described in the literature but it is mainly associated with respiratory tract infections [7,8]. Other etiologies appear to be less frequent. Explosive pleuritis is a term used to describe a rapid accumulation of exudative pleural fluid/empyema, usually within a short time. We report a rare phenomenon in which our patient developed explosive pleuritis, likely from an AVF site infection, despite the absence of recent or concurrent respiratory tract infection or other sources of infection.

Case Report

A 36-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with a past medical history of IgA nephropathy, on hemo-dialysis, with a left forearm AVF, hepatitis B, hypertension, and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. He came to the ED with sudden onset of left flank pain, which started a few hours before presentation. He described the pain as constant, non-radiating, and aggravated with deep breaths. He denied fever, chest pain, shortness of breath, cough, vomiting, diarrhea, or dysuria. He also denied any prior problems with the AVF. At presentation, his temperature was 98.5°F (36.9°C) on day 0, increasing to 102.3°F (39.0°C) on day 1, pulse 108 beats per min, respiratory rate 17 cycles per min, blood pressure 106/64 mmHg, and 99% oxygen saturation on room air. On physical examination, he was in mild distress because of pain, his abdomen was soft and non-tender, and costovertebral angle tenderness was not elicited. The AVF site was not tender and the rest of the examination was unremarkable.

An electrocardiogram demonstrated normal sinus rhythm. Initial laboratory findings revealed a white blood cell (WBC) of 10.2 k/ul, peaking to 41.9 k/ul and 36.5 k/ul on the 8th day of hospitalization before returning to 10.2 k/ul on the 19th day. Other initial laboratory results were hemoglobin 10.9 g/dl, platelets 197 k/ul, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 48, procalcitonin greater than 200 ng/dl, and C-reactive protein 4.81 mg/dl. Chemistry showed sodium 134 mmol/l, potassium 4.2 mmol/l, chloride 91 mmol/l, bicarbonate 27 mmol/l, blood urea nitrogen 66 mg/dl, and creatinine 12.4 mg/dl. Additionally, urinalysis revealed a WBC count of 1/HPF and the absence of bacteria, leukocyte esterase, and nitrate. We briefly describe the series of salient events/findings during hospitalization.

Day 0

A chest x-ray (CXR) done at 0829 h revealed clear lungs (Figure 1). A computed tomography (CT) with contrast of the abdomen and pelvis showed no evidence of acute appendicitis, diverticulitis, or mechanical bowel obstruction, and there was no ascites or evidence of portal hypertension, but both kidneys were atrophic. He had never had a previous chest CT done before the present admission.

Figure 1.

A CXR with an anterior-posterior view on day 0 at 0829 h – clear lungs.

Day 1

While in the hemodialysis unit, an open wound at the AVF fistula was noticed. The patient denied being aware of a wound at this site. The wound was swabbed and sent for cultures. It was examined and dressed regularly. It eventually grew Streptococcus group A (GAS), likely Streptococcus pyogenes. His WBC increased to 12.5 k/ul and he also became hypotensive. Blood was drawn for cultures and vancomycin and meropenem administrations were initiated. A right internal jugular (IJ) hemodialysis catheter was inserted for dialysis because of the wound at the AVF. He was transferred to the Medical Intensive Care Unit on the same day because of a significant decrease in blood pressure, but it improved after the administration of intravenous fluids. A CXR at 1440 h revealed a moderate left pleural effusion (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A CXR with an anterior-posterior view on day 1 at 1440 h – a moderate left pleural effusion (blue arrow).

Day 2

A chest CT at 0912 h showed a very large left pleural effusion with near-complete atelectasis of the left upper lobe and complete atelectasis in the left lower lobe (Figure 3). A CXR at 0930 h demonstrated a near-complete opacification of the left lung with a mediastinal shift to the right (Figure 4). The finding was consistent with a large left pleural effusion with atelectasis in the left lung. A pigtail chest tube was inserted into the left hemithorax. A follow-up CXR at 1451 h showed a left-sided pigtail catheter in situ but with a resolved large left pleural ef-fusion (Figure 5). About 1.3 L of pleural fluid was removed, with fluid analysis showing a cloudy fluid, WBC of 15 762/cumm, red blood cell of 3556/cumm, polynuclear white blood cell of 84%, glucose of 2 mg/dL, total protein of 4.2, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 9208 u/L. A serum protein was 5.1 g/dl and serum LDH was 150 u/l. Applying Light’s criteria, the pleural fluid was deemed exudative. Clindamycin was added to reduce possible toxin production by GAS.

Figure 3.

A chest CT on day 2 at 0912 h – a very large left pleural effusion (green arrow).

Figure 4.

A CXR with an anterior-posterior view on day 2 at 0930 h – a large left pleural effusion (yellow arrow).

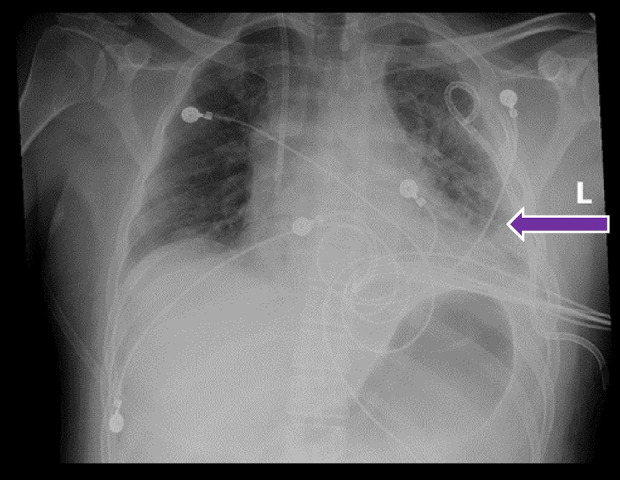

Figure 5.

A CXR with an anterior-posterior view on day 2 at 1451 h – a resolved large left pleural effusion (purple arrow).

Day 7

A repeat CXR at 0400 h showed a small, likely partially loculated, residual left effusion. The left pigtail catheter was subsequently removed but he continued to have pain at the chest tube insertion site.

Day 8

A repeat CXR at 0400 h status-post removal of the left pigtail catheter revealed a re-accumulation of pleural fluid. A video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) with pleural drainage and decortication with the insertion of 3 chest tubes (anterior, lateral and posterior) in the left hemithorax were performed.

Day 10

A chest CT at 1813 h demonstrated improved left hemithorax and loculated pleural effusion/emphysema, with a small residual area measuring 1.5 cm in thickness and a right-sided pleural effusion (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A chest CT on day 10 at 1813 h – improving left hemithorax loculated pleural effusion/emphysema with a small residual area measuring 1.5 cm in thickness (red arrow) and a stable right-sided pleural effusion (white arrow).

Day 12

The left anterior and lateral chest tubes were removed.

Day 15

The left posterior chest tube was removed.

We describe other relevant events during admission. The patient was in a state of sepsis from the first day after hospitalization to the next 2 days, based on persistent intermittent fever spikes, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension requiring intravenous fluids. Fortunately, his vital signs improved during hospitalization. Blood and pleural fluid cultures remained negative throughout the hospitalization. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed no evidence of valvular vegetations. In spite of the AVF infection, he received regular dialysis approximately every other day via a temporary jugular hemodialysis catheter as an access, but he was discharged with a right tunneled permanent catheter. The AVF was revised and repaired. Meropenem (after 12 days of administration) and clindamycin (after 11 days of administration) were switched to ceftriaxone. He received ceftriaxone for a total of 14 days, but he was discharged to continue with vancomycin for a total duration of 6 weeks. He recovered gradually and was discharged home after 27 days of hospitalization.

Discussion

AVFs are generally created surgically in patients who require long-term hemodialysis. It was first performed in the United States in 1965 [9]. Although it has been a groundbreaking procedure, it is not without complications. Such complications may be vascular or non-vascular (infectious). Vascular complications vary from ischemic steal syndrome and ischemic monomelic neuropathy to stenosis and thrombosis [3,5,6]. Other vascular complications include fistulas, hemorrhage, venous hypertension, aneurysms, and pseudoaneurysms [3,5,6]. All the aforementioned drawbacks often require revisions of the AVFs. The other major complication of AVFs is the infectious type, which is the main focus of our case.

Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis are the most familiar organisms that have been implicated [3,5]. Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species and other polymicrobial infections have also been linked to infectious complications [3,5]. They may cause local infections or systemic infections like bacteremia and sepsis with possible seeding of the organism to other organs [4]. AVF infection with explosive pleuritis is an uncommon event that has rarely been reported in the medical literature. Nonetheless, most of the reported cases of explosive pleuritis are due to underlying respiratory tract infections. In a case report by Al-Mashat et al., the patient was a 27-year-old man who developed pleural effusion within 4 days [7]. The patient had a recent history of pharyngitis caused by GAS [7]. A similar scenario was reported in a 38-year-old man who developed explosive pleuritis within 5 days, but no organisms were identified [10]. Two other case reports involved a 38-year-old man and 47-year-old man, who both developed explosive pleuritis within 24 h [8,11]. The 38-year-old patient had a recent history of pharyngitis secondary to GAS, while the 47-year-old patient had bibasilar infiltrates on imaging, with Streptococcus intermedius identified as the causative bacterium [8,11]. Upon further review of the literature, we identified more case reports, and all the patients developed explosive pleuritis after respiratory tract infections [12–17].

The pathogens identified in the reviewed case reports ranged from GAS, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Streptococcus viridans, and Candida albicans, to no identifiable organism in 1 case report [12–17]. The patients were treated with various antibiotics, including penicillins, cephalosporins, quinolones, macrolides, clindamycin, linezolid, vancomycin, and metronidazole [7,8,10–17]. Chest tubes were placed in all the patients to drain the effusions [7,8,10–17]. Additionally, other treatment modalities like thoracoscopy with decortication, thoracotomy with decortication, and intrapleural administration of fibrinolytic agents (streptokinase and urokinase) and DNAse were employed in some of the cases [7,8,10–14,17]. Table 1 is a summary of each reviewed article. Our patient developed explosive pleuritis, which was likely because of the infected AVF, despite repeated blood and pleural fluid cultures, which were negative. This is supported by an infected AVF caused by GAS with no evidence of other sources of infections like pneumonia and endocarditis (based on clinical, laboratory, radiological, and noninvasive evaluation). Despite the absence of microbiological evidence of bacteremia, we should keep in mind that repeated negative blood cultures do not exclude active bacterial infections or seeding of GAS from the AVF to the pleura.

Table 1.

Summary of the referenced articles about explosive pleuritis.

| Reference article | Age in years | Sex | Significant history before explosive pleuritis | Time to develop explosive pleuritis | Antibiotics | Causative organism | Other interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 27 | M | History of pharyngitis 7 days prior | 4 days based on a CXR and CT chest | Penicillin G and Clindamycin | GAS | CTP, VATS with decortication and drainage, and hemodialysis post-surgery |

| 8 | 38 | M | History of pharyngitis 2 days prior | 24 hours based on a CXR and CT chest | Tazobactam, Clarithromycin, and Linezolid | GAS | CTP, Thoracoscopy, and urokinase via chest tube |

| 10 | 33 | M | History of left-sided pneumonia | 5 days based on a CXR and CT chest | Outpatient –levofloxacin. Inpatient – Piperacillin/Tazobactam | No organism isolated | CTP, and tPA and DNAse via chest tube |

| 11 | 47 | M | History of abdominal distention 2 days prior | 24 hours based on a CXR and CT chest | Initial: metronidazole and ciprofloxacin.Later: vancomycin and cefepime | Streptococcus intermedius | CTP and intrapleural fibrinolytics |

| 12 | 38 | M | History of fever of 2 days and right-sided chest pain | 3 days based on a CXR and CT chest | Amoxicillin- clavulanic acid and levofloxacin | None | CTP and intrapleural streptokinase |

| 13 | 45 | M | History of one and a half week of upper respiratory infection | 24 hours based on a CXR and CT chest | Levofloxacin and Ceftriaxone | Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Viridans streptococcus, and Candida albicans | CTP and thoracotomy with decortication |

| 14 | 29 | M | History of 1-day viral syndrome 2 weeks before. Fever and chest pain 5 days before | 4 days based on a CXR and CT chest | Initial: Erythromycin, cefuroxime and vancomycin. Later: penicillin G | GAS | CTP and thoracotomy with decortication |

| 15 | 29 | F | History of sore throat and fever 9 days prior | 4 hours based on a CXR | Penicillin G | GAS | CTP |

| 15 | 33 | M | History of sore throat fever 4 days prior | 12 hours based on a CXR | Penicillin G | GAS | CTP |

| 16 | 76 | F | History of fever, productive cough, and right-sided chest pain 2 days prior | 24 hours based on a CT chest | Cefotaxime and Levofloxacin | GAS | CTP |

| 17 | 56 | M | History of right-sided chest pain and cough for 5 days. History of fever 1 day prior | 24 hours based on a CT chest. | Ampicillin/Sulbactam | No organism isolated | CTP and VATS |

M – Male; F – Female; CXR – chest x-ray; CT – computed tomography; GAS – group A streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes); CTP – chest tube placement; VATS – video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Conclusions

Our patient came in initially because of a left-sided abdominal pain. An abdomen CT revealed no obvious pathology. During hospitalization, he developed pyrexia and leukocytosis, and inflammatory markers were elevated. Oozing from his AVF was incidentally discovered and cultures grew GAS. He developed explosive pleuritis within 48 h. The fluid was drained but it reaccumulated and subsequently drained again. Initial antibiotics were vancomycin and meropenem with the addition of clindamycin. Meropenem was discontinued and switched to ceftriaxone. He was discharged on vancomycin to complete a total of 6 weeks of antibiotics. VATS with decortication was performed, the AVF was also regularly dressed and revised, and he was dialyzed via a temporary hemodialysis catheter. The uniqueness of our case is an explosive pleuritis, likely from an infected AVF site, despite negative blood and pleural cultures. It is a rare phenomenon that has rarely been described in the medical literature. We report this case so that physicians should always evaluate AVFs as the potential source of infection of other organs if there are no identifiable risk factors or other apparent sources.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Ravani P, Gillespie BW, Quinn RR, et al. Temporal risk profile for infectious and noninfectious complications of hemodialysis access. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(10):1668–77. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012121234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacRae J, Dipchand C, Oliver M, et al. Arteriovenous access: Infection, neuropathy, and other complications. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2016;3:2054358116669127. doi: 10.1177/2054358116669127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Jaishi AA, Liu AR, Lok CE, et al. Complications of the arteriovenous fistula: A systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(6):1839–50. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016040412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravani P, Quinn R, Oliver M, et al. Examining the association between hemodialysis access type and mortality: The role of access complications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(6):955–64. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12181116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padberg FT, Calligaro KD, Sidawy AN. Complications of arteriovenous hemo-dialysis access: Recognition and management. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(5):S55–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon E, Long B, Johnston K, Summers S. A case of brachiocephalic fistula steal and the emergency physician’s approach to hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula complications. J Emerg Med. 2017;53(1):66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Mashat M, Moudgal V, Hopper JA. Explosive pleurisy related to group A streptococcal infection: A case report and literature review. Pulmonary Research and Respiratory Medicine Open Journal. 2015;2(3):109–13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma BD, Kumar A, Nakra V. Explosive pleuritis: Presenting as a life-threatening condition in a young adult. Journal, Indian Academy of Clinical Medicine. 2017;18(4):290–93. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konner K. History of vascular access for haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(12):2629–35. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zoumot Z, Wahla AS, Farha S. Rapidly progressive pleural effusion. Clevel Clin J Med. 2019;86(1):21–27. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.86a.18067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatem NA, Matthews K, Foroozesh M. Rapidly progressive parapneumonic effusion: A case of explosive pleuritis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A3316. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar S, Sharath Babu NM, Kaushik M, et al. Explosive pleuritis. Online J Health Allied Scs. 2011;10(4):12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma JK, Marrie TJ. Explosive pleuritis. Can J Infect Dis. 2001;12(2):104–7. doi: 10.1155/2001/656097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson JL. Pleurisy, fever, and rapidly progressive pleural effusion in a healthy, 29-year-old physician. Chest. 2001;119:1266–69. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.4.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braman SS, Donat WE. Explosive pleuritis, Manifestation of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection. Am J Med. 1986;81:723–26. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonseca Aizpuru EM, Nuño Mateo FJ, Otero Guerra L, López de Mesa C. [Community acquired pneumonia and explosive-pleuritis] An Med Interna. 2005;22(8):401–2. doi: 10.4321/s0212-71992005000800017. [in Spanish] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa O, Gabra NI, Mahmoud O, et al. Rare and rapid: A case of explosive pleuritis. Chest. 2019;156(4):A1809–10. [Google Scholar]