Abstract

Addiction treatment has not been appreciably improved by neuroscientific research. One problem is that mechanistic studies using rodent models do not incorporate volitional social factors, which play a critical role in human addiction. Here, using rats, we introduce an operant model of choice between drugs and social interaction. Independent of sex, drug class, drug dose, training conditions, abstinence duration, social housing, or addiction score in Diagnostic & Statistical Manual IV-based and intermittent access models, operant social reward prevented drug self-administration. This protection was lessened by delay or punishment of the social reward but neither measure was correlated with the addiction score. Social-choice-induced abstinence also prevented incubation of methamphetamine craving. This protective effect was associated with activation of central amygdala PKCδ-expressing inhibitory neurons and inhibition of anterior insular cortex activity. These findings highlight the need for incorporating social factors into neuroscience-based addiction research and support the wider implantation of socially based addiction treatments.

Animal research on addiction is stymied by a translational problem. Despite strides toward understanding circuit and1,2 molecular mechanisms of addiction, treatment options remain largely unchanged3. This impasse is at least partly due to limitations of animal models of addiction, which rarely incorporate social factors into neuroscientific investigations3. In both humans and laboratory animals, adverse social interactions and social isolation promote drug self-administration and relapse, while positive social interactions (which, in laboratory animals, usually involve experimenter-controlled enriched homecage environments) tend to be protective4–7. For humans, this knowledge is incorporated into treatments such as the community reinforcement approach (CRA), which harnesses operant principles by increasing volitional contact with social reinforcers like support groups and positive work environments8.

In monkeys and rodents, drug self-administration is reliably decreased by operant availability of nondrug, nonsocial rewards such as palatable food9. Most rats choose sucrose or saccharin over heroin or cocaine, even after extended-access-induced escalation of drug intake10. We have shown that rats with a short history of palatable-food access and an extensive history of drug self-administration voluntarily abstain from heroin and methamphetamine for many days when given mutually exclusive choices between palatable food and drug11,12.

However, the exclusive use of food as the nondrug reward may limit translation13. In most humans, the rewards that compete with drugs are primarily social (for example, family, friends, employment)14. This can be modeled, because interaction with peers is highly rewarding to both rodents and monkeys15. In rodents, group housing in an enriched environment decreases drug self-administration, reinstatement, and conditioned place preference (CPP)5,16,17. The presence of a drug-naive peer in the test chamber decreases cocaine self-administration18,19. Pairing a peer with a nondrug context inhibits both expression of cocaine CPP and drug-priming-induced reinstatement of CPP20,21. However, from a human addiction perspective, the CPP model has significant limitations: it relies on noncontingent exposure to low drug doses for 3–4 d, not resembling human drug-use patterns of long-term voluntary drug self-administration that often increases over time.

These studies5,16–21 show that experimenter-controlled or administered social interaction either outside or inside the testing cage can decrease drug reward and reinstatement or relapse. However, it is unknown whether drug self-administration can be reduced by giving rats volitional or subject-controlled operant choice between drug and social reward, a setup that would more closely model the human condition3. Here we developed an operant model involving series of choices between drug (methamphetamine or heroin) and interaction with a familiar or novel conspecific. We report that the availability of a social-reward choice eliminated drug self-administration, even in rats that had met criteria for ‘addiction’22, under diverse conditions that included social housing between the choice sessions. Furthermore, after intermittent access drug self-administration23, the rats’ addiction score did not predict their liability to shift from social to drug preference when we devalued social interaction by delay or punishment. Social-choice-induced abstinence also prevented incubation of methamphetamine craving and relapse24, and this protective effect was associated with recruitment of protein kinase C-δ (PKCδ)-expressing inhibitory neurons in central amygdala (CeA)25 and inhibition of activity in anterior ventral insular (AIV) cortex; these regions are critical to relapse after food- choice-induced abstinence26.

Results

Volitional operant social reward reliably prevents drug self-administration

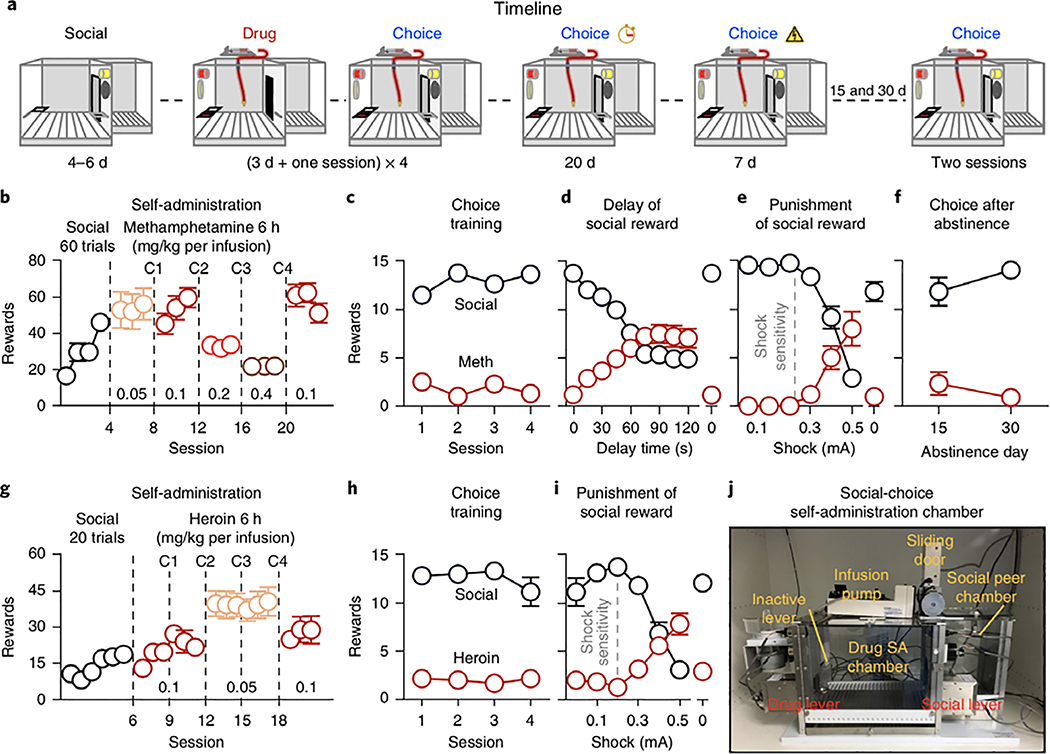

In Experiment 1 (Fig. 1a), we used the established extended-access (6h per d) addiction model27 to determine whether methamphetamine or heroin self-administration would be prevented by operant access to social interaction (see Methods and Supplementary Note for experimental details). We then devalued the social reward by either increasing the delay after social-lever press or by punishment of 50% of social-lever presses with footshock of increasing intensity. Social reward prevented methamphetamine self-administration independent of drug unit dose (Fig. 1b,c). Methamphetamine self-administration resumed only if there was a long delay before social reward or if social-lever presses were punished (Fig. 1d,e). Rats preferred social interaction over methamphetamine even after either 15 or 30 d of forced abstinence (Fig. 1f). Social reward also prevented heroin self-administration independent of sex and drug unit dose (Fig. 1g,h). As with methamphetamine, heroin self-administration resumed only if social-lever presses were punished (Fig. 1i). For a description of the custom-made ‘social self-administration’ chambers, see Fig. 1j and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 |. Preference for drug vs. social reward: effects of drug dose, delay of social reward, punishment of social-reward choice, or forced abstinence.

a, Timeline of the experiments. b, Self-administration training (rewards: social or drug infusion). Number of social rewards (2 h) or methamphetamine (meth) infusions (6 h). c,h, Discrete-choice sessions during training. Social rewards and methamphetamine or heroin infusions earned during four discrete-choice sessions performed after 3 consecutive days of drug self-administration training (15 trials per session). d, Delay of social reward. Social rewards or methamphetamine infusions earned during ten choice sessions (two sessions per timepoint) during which we progressively increased the delay of social reward. e,i, Punishment of social reward. Social rewards and methamphetamine or heroin infusions earned during seven choice sessions in which 50% of lever presses for social reward were punished with footshocks of increasing intensity. f, Choice after forced abstinence. Social rewards and methamphetamine infusions earned during two choice sessions after 14 and 29 d of forced abstinence. g, Self-administration training (social reward or heroin). Number of social rewards (40 min) and heroin infusions (6 h). j, Social-choice self-administration chamber. The chamber has two active levers (drug or social), one inactive lever, two discriminative cues (red light for drug, white light for social), two conditioned stimuli (white light for drug, tone for social), a pump, and a social-peer chamber separated by a sliding door (see also Supplementary Fig. 1). C, choice; SA, self-administration; methamphetamine, n = 10 males; heroin, n = 6 females and 6 males. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Statistical details are included in Supplementary Table 1.

Methamphetamine

Over sessions, male rats increased their number of social interaction rewards and (in separate sessions) methamphetamine infusions at 0.05 or 0.1mg/kg. Subsequent increases in the unit dose of methamphetamine caused the expected decrease in number of drug infusions (see Supplementary Table 1 for complete reporting of the statistical analyses). During the four choice training sessions that separated the escalating doses of methamphetamine, the rats showed a strong preference for social interaction, independent of methamphetamine dose (reward: F1,9=201.1, P<0.001). During the delay-discounting phase, preference for social inter- action decreased as delay increased (reward×delay: F9,81=30.1, P<0.001). Preference for social reward resumed during a subsequent regular choice session with no delay. During the punishment phase, preference for social interaction decreased as shock intensity increased (reward×shock intensity: F6,54=30.4, P<0.001). Preference for social reward resumed during a subsequent no- shock choice session. In choice tests after 15 or 30 d of homecage abstinence, rats maintained their preference for social interaction (reward: F1,8=69.5, P<0.001).

Heroin

Over sessions, male and female rats increased their number of social interaction rewards (session: F5,50=32.0, P<0.001). Both sexes maintained stable heroin intake over sessions but increased their intake when we decreased the unit dose from 0.1 to 0.05 mg/kg. In the four choice training sessions during training, both sexes showed strong preferences for social interaction over heroin (reward: F1,10=65.1, P<0.001). During the punishment phase, preference for social interaction decreased with increasing shock intensity in both sexes (reward×shock intensity: F6,60=29.1, P<0.001). For both sexes, preference for social reward resumed during a subsequent no-shock choice session.

Experiment 1 demonstrates that rats trained in an established addiction model that leads to escalation of drug intake27 will voluntarily abstain when given mutually exclusive choices between drug and rewarding social interaction. This effect persisted through at least 4 weeks of forced abstinence and could only be reversed by delay of social reward or probabilistic punishment (and this reversal did not occur in all rats).

Social reward prevents drug self-administration in both “addicted” and “non-addicted” rats

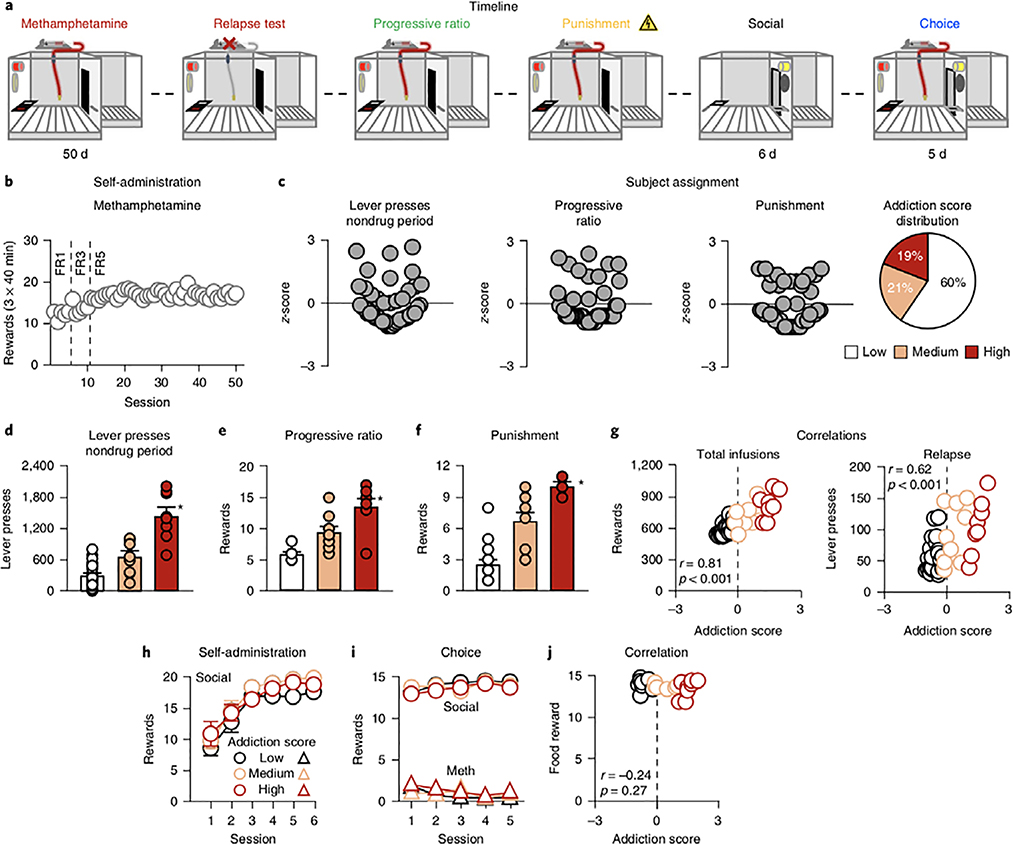

Experiment 2 (Fig. 2a) was a more stringent test of the effect of social reward, using rats identified as addicted in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV (DSM-IV)-based model22,28. We trained male rats for methamphetamine self-administration (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a) in 50 daily sessions that included three 40-min ‘drug periods’ separated by two 15-min ‘nondrug’ periods (during which we measured non-reinforced active-lever presses). We then tested relapse to methamphetamine seeking in an extinction session, motivation for methamphetamine in a progressive-ratio task, and resistance to punishment (Supplementary Note). To determine the addiction score of each rat, we used three measures based on refs22,28: (i) total non-reinforced lever presses during two daily nondrug periods under the fixed-ratio 5 (FR5) schedule, (ii) number of drug rewards earned under the progressive-ratio schedule, and (iii) punishment responding (operationally defined as the number of methamphetamine rewards earned when 50% of lever presses led to 0.3- and 0.45-mA footshock; Fig. 2c–f). These measures were highly correlated with each other (Pearson’s r=0.62–0.77, P<0.001; Supplementary Table 2). We calculated a z-score for each rat on each measure and then calculated the mean z-score across the three measures to derive the rat’s addiction score. We classified rats as highly addicted or ‘High’ (mean z-scores>1; n=8 of 42 rats, ≈19%), moderately addicted or ‘Medium’ (mean z-score between 1 and −0.1; n=9 of 42 rats, ≈21%), and mildly addicted or ‘Low’ (mean z-score<−0.2; n=25 of 42 rats, ≈60%; Fig. 2c). The addiction score was highly correlated with total meth- amphetamine infusions under the FR5 reinforcement schedule (Pearson’s r=0.81, P<0.001) and number of non-reinforced lever- presses during the relapse test (Pearson’s r=0.62, P<0.001; Fig. 2g). Finally, we trained some or all rats from each group (8 High, 6 Medium, 10 Low) for social self-administration (six sessions; Fig. 2h) and then determined drug versus social-reward preference in five discrete-choice sessions (Fig. 2i).

Fig. 2 |. Preference for methamphetamine vs. social reward in addicted and nonaddicted rats.

a, Timeline of the experiment. b, Methamphetamine self- administration training. Number of methamphetamine infusions during the three 40-min sessions. The first 6 d of training were completed under an FR1 reinforcement schedule, the next 5 d under an FR3 schedule, and the remaining 39 d under an FR5 schedule. c, Subject assignment. Individual z-score measures for total active-lever presses during the nondrug period, progressive ratio, and punishment; percentages of rats classified as Low, Medium, and High addiction-score groups (total n = 42). d, Total active-lever presses during the nondrug period. Total number of active-lever presses during the two 15-min nondrug periods under the FR5 schedule for the three groups (Low n = 25; Medium n = 9; High n = 8). e, Progressive ratio. Number of methamphetamine infusions earned during progressive-ratio testing for the three groups (Low n = 25; Medium n = 9; High n = 8). f, Punishment. Number of methamphetamine infusions earned during the last two 40-min sessions with 0.30- and 0.45-mA footshock for the three groups. g, Correlations. Pearson correlations between individual addiction scores and total number of methamphetamine infusions during FR5 self-administration schedule (left) and the number of non-reinforced lever presses during the relapse test (right). The x axis corresponds to the addiction score (mean z-scores for all three measures; see Results) and the y axis corresponds to the number of rewards or number of lever presses, respectively. h, Social self-administration training. Number of social rewards earned during the 40-min sessions (Low n = 10; Medium n = 6; High n = 8). i, Discrete-choice sessions. Social rewards and methamphetamine infusions earned during the five discrete-choice sessions performed after social self-administration. j, Correlation. Pearson correlations between individual addiction scores and social rewards earned during the choice session. The x axis corresponds to the addiction score (mean z-scores for all three measures; see Results) and the y axis corresponds to the social rewards earned during the choice session. Different from the other addiction- score groups, *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± s.e.m. See also Supplementary Fig. 2. Statistical details are included in Supplementary Table 1.

The main finding was that the rats strongly preferred social interaction over methamphetamine and this effect was independent of addiction-score group (Fig. 2j). By design, the three groups differed on total active-lever presses during the nondrug off-period (F2,39=45.5, P<0.001), progressive-ratio responding (F2,39=46.6, P<0.001), and punishment responding (F2,39=55.5, P<0.001; Fig. 2d–f). They did not differ on social self-administration (session: F5,105=54.0, P<0.001; no effect of group or group×session; Fig. 2h) or drug versus social-reward choice (reward type: F1,21=1641.8, P<0.001; no effect of group or interactions between the three factors (group×reward×session); Fig. 2i). Thus, even rats identified as addicted by the established model DSM-IV rat addiction model22,28 chose to abstain from methamphetamine when given a choice of interaction with a peer.

Addiction score does not predict robustness of social preference

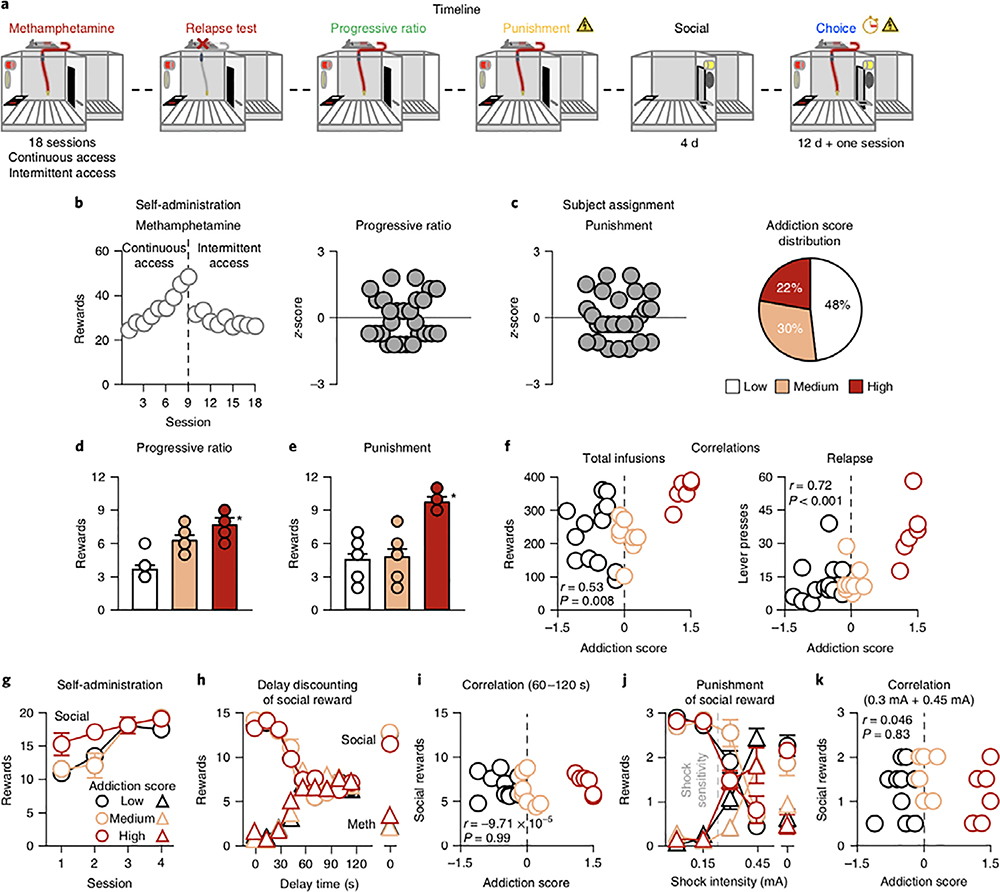

In Experiment 3 (Fig. 3a), we asked whether rats with high addiction scores would be more vulnerable to reversal of their preference for social over drug reward. We took an ‘individual differences’ approach similar to that of Experiment 2, using an intermittent-access-based drug self-administration model intended to model human binge-like use of psychostimulants23. In this model, rats are given 5 min of access to drug (ON period) every 30 min during 6-h daily sessions23. This results in binge-like self-administration, increased progressive-ratio responding, and proneness to reinstatement of drug seeking23,29.

Fig. 3 |. High addiction score does not predict lower social preference.

a, Timeline of the experiment. b, Methamphetamine self-administration training. Number of methamphetamine infusions (6 h) during the continuous extended access and intermittent access self-administration training. c, Subject assignment. Individual z-score measures for progressive ratio and punishment; percentages of rats classified as Low, Medium, and High addiction-score groups (total n = 27). d, Progressive ratio. Number of methamphetamine infusions earned during progressive-ratio testing (Low n = 13; Medium n = 8; High n = 6). e, Punishment. Number of methamphetamine infusions earned during the last two 30-min sessions with 0.30- and 0.45-mA footshock. f, Correlations. Pearson correlations between individual addiction scores and total number of methamphetamine infusions during intermittent self- administration access (left) and the number of non-reinforced lever presses during the relapse test (right). The x axis corresponds to the addiction score (mean z-scores for the two measures; see Results) and the y axis corresponds to the number of rewards or number of lever presses, respectively. g, Social self-administration training. Number of social rewards earned during the 40-min sessions (Low n = 11; Medium n = 7; High n = 6). h, Delay discounting of social reward. Social rewards or methamphetamine infusions earned during 12 choice sessions (three sessions at baseline) in which we progressively increased the delay of social reward. i, Correlation. Pearson correlations between individual addiction scores and social rewards earned during the choice session. The x axis corresponds to the addiction score (mean z-scores for the two measures; see Results) and the y axis corresponds to the social rewards earned during the choice session, as measured in the choice procedure from 60 to 120 s (see Methods). j, Punishment of social reward. Social rewards and methamphetamine infusions earned during the choice sessions with increasing shock intensity from 0 to 0.45 mA and then back to 0. k, Correlation. Pearson correlations between individual addiction scores and social rewards earned during the choice session. The x axis corresponds to the addiction score (mean z-scores for the two measures; see Results) and the y axis corresponds to the social rewards earned during the choice session, as measured in the choice procedure for 0.3-mA and 0.45-mA footshocks (see Methods). Different from the other addiction-score groups, *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± s.e.m. See also Supplementary Fig. 2. Statistical details are included in Supplementary Table 1.

We trained male rats to self-administer methamphetamine first using the escalation model27 (9 days, 6 h/d) and then using the intermittent-access drug self-administration model23 (9 days, 6 h/d, 5 min ON and 25min OFF; Fig. 3b). We determined a modified addiction score that only included the number of drug rewards earned under the progressive-ratio schedule and punishment responding (operationally defined as the number of drug rewards earned when 50% of lever presses led to 0.3- and 0.45-mA footshock; Fig. 3c–e). The two measures were intercorrelated (Pearson’s r=0.41, P=0.03; Supplementary Table 3). We calculated mean z-scores across the two measures, and then classified rats as High (mean z-scores>1; n=6 of 27 rats, ≈22%), Medium (mean z-score between 1 and − 0.1; n=8 of 27, ≈30%), and Low (mean z-score<−0.2; n=13 of 27 rats, ≈48%; Fig. 3c–e). The modified addiction score correlated with total methamphetamine infusions during the 9-d intermittent access (Pearson’s r=0.53, P=0.008) and number of non-reinforced lever-presses during the relapse test (Pearson’s r=0.72, P<0.001; Fig. 3f). We trained some rats from each group (6 High, 7 Medium, 11 Low) for social self-administration (four sessions; Fig. 3g) and ran discrete-choice sessions using delay or punishment of social reward (Fig. 3h–k).

As in Experiments 1 and 2, the rats strongly preferred social interaction over methamphetamine, and this effect was independent of the modified addiction-score group. More importantly, high addiction scores did not predict lower social preference. By design, the three groups differed on progressive-ratio responding (F2,24=40.4, P<0.001) and punishment responding (F2,24=21.4, P<0.001; Fig. 3c,d). The groups did not differ on social self- administration (group × session: F6,63=1.43, P=0.2; Fig. 3g) or on drug versus social-reward choice during delay discounting (session×reward: F16,168=93.6, P>0.001), but we found no effect of group or interactions between group and the other factors (Fig. 3h). For punishment of social reward, the analysis showed a significant session × reward × group interaction (F6,63=2.3, P>0.04) due to somewhat higher resistance to punishment of social reward in the medium group (Fig. 3j). There were no significant correlations between the modified addiction score and social-preference score in either procedure (Fig. 3i,k). Experiment 3 demonstrates that after extended drug self-administration, vulnerability to devaluation of social reward is independent of established measures of addiction in rats.

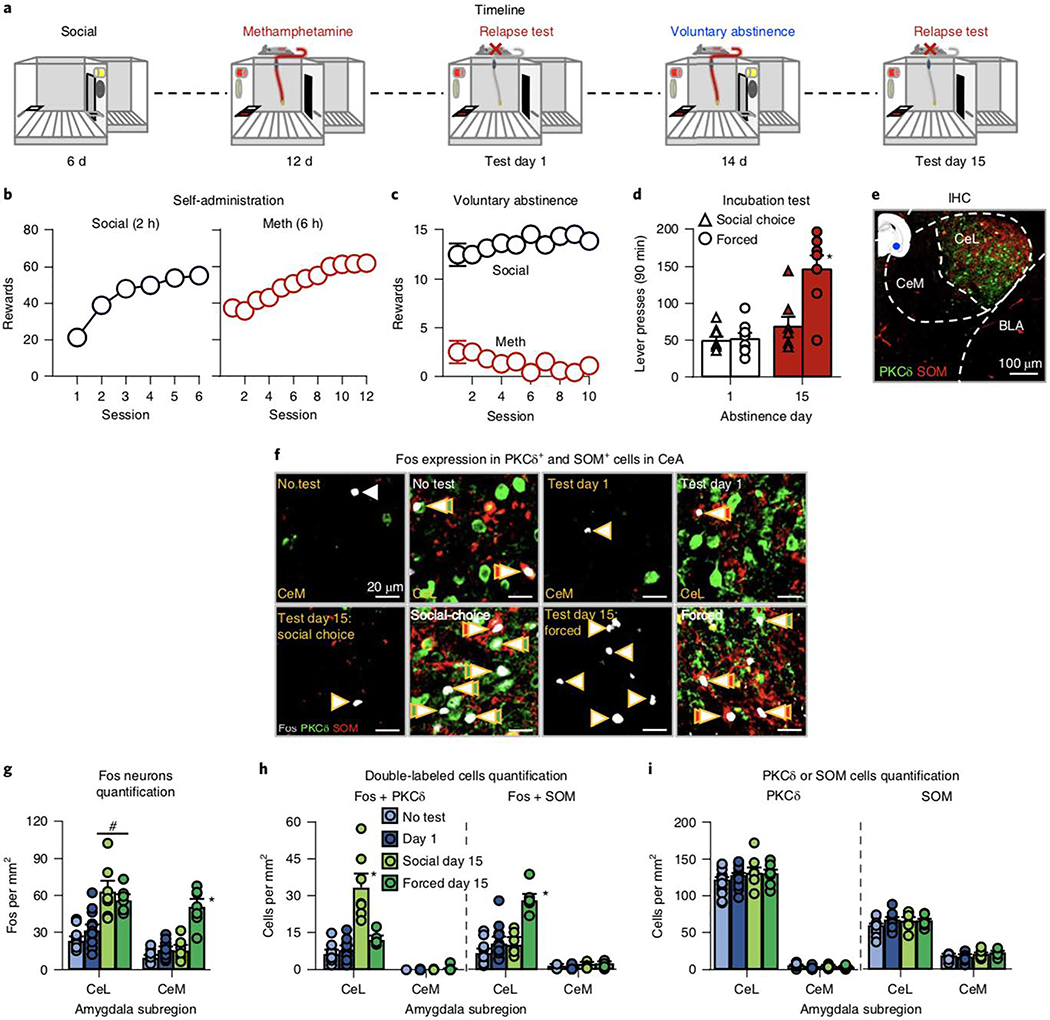

Social-based voluntary abstinence prevents incubation of methamphetamine craving

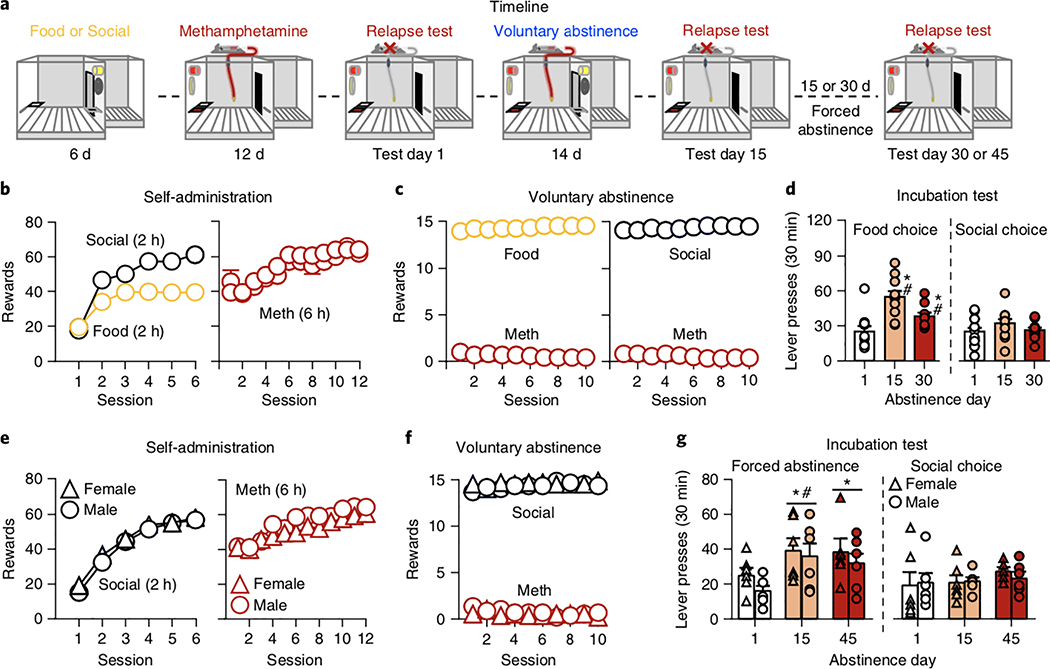

In Experiment 4 (Fig. 4a), we determined whether social-choice-induced voluntary abstinence would pre- vent incubation of methamphetamine craving30. The experiment had four phases (Fig. 4a): self-administration training (3 weeks), voluntary abstinence (14 d), relapse tests 1 d after the last self- administration session and 1 d after the last voluntary abstinence session, and relapse tests after 15 or 30 d of homecage forced abstinence (see Supplementary Note). In Experiment 4a, we compared food-choice-induced voluntary abstinence31 versus social-choice- induced voluntary abstinence. In Experiment 4b, we compared social-choice voluntary abstinence versus homecage forced abstinence (the condition used in most previous studies of incubation32; see also Experiment 5).

Fig. 4 |. Effect of social-choice voluntary abstinence on incubation of methamphetamine craving.

a, Timeline of the experiment. b,e, Self-administration training (rewards: social or drug infusion). Number of social or food (2 h) rewards and methamphetamine infusions (6 h). c,f, Voluntary abstinence. Number of food or social rewards and methamphetamine infusions earned during the 10 discrete-choice sessions. d,g, Incubation and relapse test. Active-lever presses during the 30-min test sessions. During testing, active-lever presses led to contingent presentation of the light cue previously paired with methamphetamine infusions during training, but not methamphetamine infusions (extinction conditions). After the test on day 15, we returned the rats to their home cages for 14 or 29 d of forced abstinence and tested again on day 30 or 45, respectively. Different from active lever on test day 1, *P < 0.05. Different from active lever from the social-choice voluntary abstinence group on test day 15, #P < 0.05. Food-choice-induced vs. social- choice-induced abstinence n = 10 and 12 males, respectively; forced vs. social-choice abstinence n = 6 females per group and 6 males/group. Data are mean ± s.e.m. See also Supplementary Figs. 3 and 5. Statistical details are included in Supplementary Table 1.

Food-choice-induced versus social-choice-induced voluntary abstinence

Over sessions, male rats increased the number of food, social, and methamphetamine rewards (Fig. 4b). The rats showed strong preferences for either food or social reward over methamphetamine during training (Supplementary Fig. 3a), as well as during voluntary abstinence (Fig. 4c). In 30-min relapse tests, rats in the food- choice but not social-choice condition sought methamphetamine more on abstinence day 15 than on day 1 (Fig. 4d), as reflected in a three-way interaction: abstinence condition (food choice or social choice)×day (1 and 15)×lever (active and inactive; F1,20=7.6, P=0.01). On day 30, after 15 d of homecage forced abstinence, active-lever pressing was higher in the former food-choice group than in the former social-choice group (Fig. 4d).

After the relapse test on day 30, we undertook satiety-based devaluation33 of food or social reward by either providing palatable food in the homecage before sessions for increasing durations (1h, 3h, 1 d, 3 d, and 6 d) or by cohousing each rat and its ‘self-administered’ social partner for the same time periods. Satiety-based devaluation of food increased drug choice; whereas satiety-based devaluation of a social partner did not (Supplementary Fig. 3b; interaction between abstinence condition (food, social) and homecage duration of reward availability, F5,90=7.3, P<0.001). We also tested progressive-ratio responding for food, social, and methamphetamine reward, and found no differences between the three reward types (all P>0.1; Supplementary Fig. 3c).

Social-choice-induced voluntary abstinence versus forced abstinence

Using male and female rats, we replicated and extended the unexpected finding from Experiment 4a on long-lasting inhibition of incubation of methamphetamine craving. The comparison condition in Experiment 4b (and Experiment 5 below) was homecage forced abstinence, as in other incubation of drug craving studies32. Over sessions, both sexes increased their number of social and methamphetamine rewards (Fig. 4e). During voluntary abstinence, both sexes strongly preferred social reward over methamphetamine (Fig. 4f). In 30-min relapse tests, rats in the forced-abstinence but not social-choice abstinence condition sought methamphetamine more on day 15 than on day 1 (Fig. 4g; abstinence condition×day×lever, F1,20=6.0, P=0.02; no interactions with sex). After another 30 d of homecage forced abstinence, active-lever pressing was somewhat higher in the original forced-abstinence group than in the original social-choice group, but this effect was not statistically significant (P=0.058).

Thus, social-choice-induced voluntary abstinence prevented incubation of craving, an effect that persisted for at least 4 additional weeks of homecage forced abstinence. Additionally, social housing for up to 6 d had no effect on the strong preference for social interaction over methamphetamine.

Neuronal correlates of the inhibitory effect of social-choice-induced abstinence on incubation of methamphetamine craving

We hypothesized that the inhibitory effect of social choice on incubation involves neuronal activity in CeA, a brain region critical to incubation across drug classes34. We used protein immunohistochemistry (Experiment 5a) and RNAscope in situ hybridization (Experiment 5b, an independent replication at the mRNA level) to test whether social-choice-induced voluntary abstinence recruits PKCδ+ neurons in the lateral CeA subdivision (CeL)25 during the late-abstinence relapse test. Recruitment of these neurons would be expected to inhibit output neurons in medial CeA subdivision (CeM) and somatostatin (SOM)-expressing neurons in CeL, both of which play a role in appetitive behaviors35. In Experiment 5a, we found that during the relapse tests, prior social-choice-induced voluntary abstinence inhibited Fos expression in CeM (see below). Thus, we tested the generality of this effect to other brain areas involved in incubation and cue-induced drug seeking: AIV and dorsal anterior insular cortex, ventral and dorsal medial pre- frontal cortex (mPFC), anterior cingulate cortex, lateral and medial orbitofrontal cortex, and basolateral amygdala2,26,32,36.

As in Experiment 4, the male rats in Experiment 5a and 5b (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 4a) increased their number of social rewards and methamphetamine infusions during training and showed complete or near-complete suppression of methamphetamine self-administration during choice sessions (Fig. 5b,c and Supplementary Fig. 4b,c). In Experiment 5a, active-lever presses after forced abstinence were higher on day 15 than on day 1 and were also higher than on day 15 of social-choice voluntary abstinence (Fig. 5d; abstinence condition×day×lever: F1,26=7.2, P=0.01). The active-lever presses for the social-choice group did not differ between day 1 and 15 (Fig. 5d). In Experiment 5b, active-lever presses were higher on day 15 in forced abstinence rats than in social-choice rats (Supplementary Fig. 4d; abstinence condition: F1,12 = 5.7, P = 0.03) and approaching significant interaction of abstinence condition×lever (F1,12=4.5, P=0.056).

Fig. 5 |. Effect of social-choice voluntary abstinence on Fos expression, and Fos + PKCδ or Fos + SoM in CeL and CeM: immunohistochemistry.

a, Timeline of the experiment. b, Self-administration training (rewards: social or drug infusion). Number of social rewards (2 h) or methamphetamine infusions (6 h). c, Voluntary abstinence. Number of social rewards or methamphetamine infusions earned during the ten discrete-choice sessions. d, Incubation and relapse test. Lever presses on the active lever during the 90-min test sessions on abstinence days 1 and 15 (no-test, n = 15; day 1, n = 16; day 15 forced- and social-induced-abstinence, n = 7 rats per group). Different from the other groups, *P < 0.05. e, Immunohistochemistry (IHC). Representative photomicrographs of PKCδ and SOM expression in CeL. BLA, basolateral amygdala. Scale bar, 100 μm. f, Representative CeL and CeM photomicrographs of Fos expression in PKCδ+ and SOM+ neurons in the no-test group (top left, n = 15), test day 1 (top right, n = 16), social-choice day 15 group (bottom left, n = 7), and forced abstinence day 15 group (bottom right, n = 7). Arrows, representative cells; double arrows, double-labeled cells. Fos, white; PKCδ, green; SOM, red. Scale bar, 20 μm. g, Fos neuron quantification. Number of Fos-immunoreactive (IR) neurons per mm2 in the CeL and CeM. h, Quantification of double-labeled cells. Number of Fos + PKCδ-IR or Fos + SOM-IR double-labeled neurons per mm2 in the CeL and CeM. i, PKCδ and SOM quantification. Number of PKCδ-IR or SOM-IR in CeL and CeM. Different from other groups, *P < 0.05; Different from no-test and day 1, #P < 0.05. Data are mean ± s.e.m. See also Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5. Statistical details are included in Supplementary Table 1.

Fos immunohistochemistry

In Experiment 5a, we analyzed Fos expression and double-labeling of Fos+PKCδ and Fos+SOM (Fig. 5e,f) in four groups of rats: no test (brain taken after either 1 d of abstinence or 14 d of forced or voluntary abstinence); abstinence test day 1; forced abstinence test day 15; and social-choice-induced voluntary abstinence test day 15. In CeL, Fos expression was higher after 14 d of forced or voluntary abstinence than after 1 d of abstinence or no test. In CeM, Fos expression was higher after 14 d of forced abstinence than in the other three groups (group×CeA subregion: F3,41=35.0, P<0.001; Fig. 5g). For Fos+PKCδ and Fos+SOM double-labeling, we only analyzed CeL data, because of the low expression of PKCδ and SOM and very low double-labeling in CeM (Fig. 5f–i). In both cases, there was an effect of group (F3,41 = 35.4, P<0.001 and F3,41=27.7, P<0.001, respectively), reflecting high Fos + PKCδ in the social-choice day 15 group and high Fos + SOM in the forced-abstinence day 15 group (Fig. 5f).

The main finding in the analysis of the other brain areas was that day 15 relapse-test-induced Fos expression in the AIV, but not in other brain regions, was lower in the social-choice group than in the forced-abstinence group (Supplementary Fig. 5a–g). There were main effects of group for AIV (F3,40=8.5, P<0.001), dorsal anterior insular cortex (F3,40=7.8, P<0.001), medial orbitofrontal cortex (F3,40 = 14.7, P < 0.001), lateral orbitofrontal cortex (F3,40=17.4, P<0.001), dorsal mPFC (F3,40=7.0, P=0.01), ventral mPFC (F3,40=3.7, P=0.02), anterior cingulate cortex (F3,40=5.2, P=0.004), and basolateral amygdala (F3,40=31.3, P<0.001). Post hoc analysis showed differences between the social-choice and forced-abstinence groups for the AIV (P<0.05) but not the other regions (all P > 0.05).

Fos mRNA (RNAscope)

In Experiment 5b, we used three groups of rats: no test (drug-naive social-partner rats), forced-abstinence test day 15, and social-choice voluntary abstinence test day 15. As in Experiment 5a, Fos in CeL was higher in both abstinence groups than in the no-test group, while Fos in CeM was higher in the forced-abstinence group than in the other two groups (Supplementary Fig. 4e–h; group: F2,18=46.3, P<0.001; CeA subregion: F1,18=6.7, P=0.02). In CeL, Fos+PKCδ double-labeling was higher in the social-choice day 15 group than in the other groups (F2,18=38.2, P<0.001), and Fos+SOM was higher in the forced-abstinence day 15 group than in the other groups (F2,18=18.7, P<0.001; Supplementary Fig. 4f–h).

Experiment 5 demonstrates that the inhibitory effect of social- choice-induced voluntary abstinence on incubation of craving was associated with increased Fos expression in CeL PKCδ+ inhibitory neurons25 during the relapse tests. In contrast, homecage forced abstinence was associated with Fos expression in both CeL SOM+ neurons and CeM output neurons, presumably leading to long-lasting incubation of methamphetamine craving. Social-choice-induced voluntary abstinence also selectively decreased neuronal activity in AIV, a region critical for relapse after food-choice-induced abstinence26.

Discussion

We have introduced an operant model of choice between drugs and social interaction in rats that had been self-administering both. When the two rewards were presented as a series of mutually exclusive choices, the rate of drug abstinence was almost 100%. This occurred independent of sex, drug class (psychostimulant, opioid), drug dose, self-administration training conditions, length of abstinence, or housing conditions, including social housing. Social reward also eliminated drug self-administration in rats identified as addicted in our modification of the established DSM-IV-based addiction model22. Rats resumed drug self-administration if we delayed the social reward or if we probabilistically punished the response for it. However, the threshold for that resumption, which differed across rats, was not predicted by the addiction scores. Finally, after 2 weeks of choice-induced abstinence, rats were protected against incubation of methamphetamine craving for at least 1 month past the removal of the social choice. This protective effect was associated with recruitment of inhibitory CeL PKCδ+ neurons and decreased activation of AIV neurons during the relapse tests.

How does the social-choice model relate to other animal models of addiction?

Our model was based on two lines of research in which drug seeking in rats had been reduced: environmentally enriched group housing5,37 and choice between drug and palatable food9,10. These two lines of research had not been integrated (except in one lab, using monkeys7). Additionally, these lines of research were rarely incorporated into neuroscience studies of addiction7,13,38, which usually rely on either experimenter-administered drug-exposure models (locomotor sensitization, CPP) or drug self-administration in single-housed rats with no alternative rewards3,13.

These traditional self-administration models identify nearly all rats as avid users of opioids and psychostimulants39, and these models have not fared well as screens for new treatments3. Our model starts at the other extreme—the abstinence rate of rats with immediate access to a conspecific is almost 100%—but we lowered this by devaluing the social reward. When we introduced a delay in access to the conspecific, the abstinence rate decreased to 40–50%, consistent with findings in humans treated with CRA and contingency management8. With those parametric adjustments in place, rats that choose drug over delayed social reward in our model may be an ideal testing ground for pharmacological or other biologically based interventions. Thus, while demonstrating that social reward has remarkable protective and restorative effects, our model also clears a much-needed path toward understanding and treating addiction in people who appear to benefit less from those protective effects. Additionally, addiction measures from established models (for example, intense drug taking or drug seeking and resistance to punishment of drug self-administration) did not predict vulnerability to devaluation of social reward in our model, suggesting that we are assessing an independent dimension of addiction vulnerability.

How does social-choice reward prevent incubation of methamphetamine craving?

Two weeks of voluntary abstinence prevented incubation of methamphetamine craving for many weeks. This was unexpected because, in this and previous studies, we found reliable incubation of methamphetamine craving after discontinuation of a seemingly successful food-choice-induced voluntary abstinence procedure31,40. Even when incubation of cocaine craving has been decreased by homecage social housing in an enriched environment, incubation reemerges after several weeks of single housing41,42.

To explore a possible mechanistic explanation, we examined the CeA, which is involved in incubation of drug craving after forced abstinence32 and in drug seeking after food-choice-induced voluntary abstinence26. We found that social-choice-induced voluntary abstinence selectively induced Fos in inhibitory CeL PKCδ+ neurons during late abstinence relapse tests. This presumably prevented activation of CeL SOM+ neurons and CeM output neurons25, which are involved in appetitively motivated behaviors via downstream targets35. In contrast, homecage forced abstinence led to recruitment of both CeM output neurons and CeL SOM+ neurons, presumably leading to long-lasting incubation of methamphetamine craving. Inhibition of incubation of craving after social-choice-induced abstinence was also associated with decreased activation of AIV, whose glutamatergic projection to CeL is critical to relapse after food-choice-induced voluntary abstinence26. Thus, social-choice experience may inhibit incubation via long-lasting decreases in responses of the AIV-to-CeL projections to drug cues.

What does the social-choice model imply for human addiction and treatment?

In humans, addiction develops and persists despite the availability of social contact, including contact with abstinent peers. Why do rats in the social-choice model abstain from drug almost entirely (unless social reward is delayed or punished)? We do not think the difference is attributable to the fact that the rats are faced with a series of mutually exclusive choices, because rats can allocate such choices when more than one reward is highly valued43.

We suspect, instead, that humans evaluate social interaction using a global frame of reference44 in which the most highly valued outcome is what sociologists call ‘a stake in conventional life’45—that is, meaningful participation in society or its institutions, above and beyond the momentary presence or absence of a companion. This social reward is rarely as immediate or concrete as drug reward; when it is chosen over drug use, the choice is made in terms of a temporally integrated ‘bundle’ of expected immediate and delayed outcomes46. This sort of ‘choice bundling’ is a double-edged sword: in people who expect to gain or maintain a stake in conventional life, choice bundling may protect against addiction45, but in people whose expectations are bleak, choice bundling may help rationalize self-destructive behavior47, including drug use. These considerations are largely absent for rats, whose choices are rarely controlled by outcomes that are delayed by more than a minute or two except for conditioned taste aversions. Rats also do not have a cultural frame of reference for the reward value of social interaction. We think these two species differences—one in time horizons, one in a cultural frame of reference—largely account for the fact that simple access to a conspecific is more protective against drug choice for rats than for humans.

Many addicted humans do respond well, however, to behavioral treatments that render social reward immediate and predictable. This is the principle underlying CRA8, which is typically combined with contingency management48. Unlike rats, addicted humans can also benefit from cognitive treatments that make distal nondrug rewards (including social rewards) more salient during watershed moments of choice; this is central to cognitive–behavioral therapy and to acceptance and commitment therapy. Our findings under-score the soundness of all these approaches and suggest that CRA, in particular, merits more attention as an addiction treatment.

But not all human addicts respond to social-reinforcement-based treatments49, and not all human drug users with a stake in conventional life are protected against the development of addiction45. There is a nontrivial number of addicted humans for whom choice processes become unresponsive to any realistically achievable arrangement of contingencies; this is why, even in the highest socioeconomic strata, with ample social rewards available, rates of sustained remission do not approach 100%. These cases might be the far end of continuum of individual differences in normal processes of choice44 alternatively, these cases might reflect discrete, heterogeneous pathologies. Either way, small devaluations of social reward in our model can identify such cases and will be useful in attempts to understand them.

Concluding remarks

We used established models of drug addiction22,23,27, relapse, and craving34 to demonstrate that operant access to social reward prevented ‘compulsive’ self-administration of heroin and methamphetamine in addicted rats, as well as preventing incubation of methamphetamine craving and relapse. These observations highlight the importance of incorporating social factors into neuroscientific studies of addiction3,7 and illustrate the profound impact of positive social interactions on both addictive behavior and brain responses to drug-associated cues. From a clinical perspective, our findings support wider implementation of social-based behavioral treatments, which include not only CRA but also innovative social-media approaches, like those being implemented for other psychiatric disorders50 to provide social support before and during drug-seeking episodes.

Material and Methods

Subjects

We used male and female Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, total n = 357, of which 222 were ‘residents’ (202 male and 20 female) and 135 were ‘social partners’ (116 males and 19 females)), weighing 150–175 g upon arrival. We housed the rats two per cage by sex for 2–3 weeks before the experiments and then individually housed them starting 1 week before social or drug self-administration for the duration of the experiment; we randomly assigned rats to the resident (drug user) and social partner (drug naive) groups. In Experiments 2 and 3, the social partners were rats of the same age and weight, but they were not previously housed with the resident drug-experienced rats. We maintained the rats on a reverse 12-h light/dark cycle (lights off at 9:30 a.m.) with free access to standard laboratory chow and water. Our procedures followed the guidelines outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition; http://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/Guide-for-the-Care-and-Use-of-Laboratory-Animals.pdf). This study was approved by the NIDA IRP Animal Care and Use Committee. We excluded 26 drug-experienced rats (24 males and 2 females) due to illness (n = 25) or failure to acquire self-administration (n = 1) and 6 drug-naive rats (5 males and 1 female) due to the exclusion of their resident (drug user) partner.

Surgery

We anesthetized the rats with isoflurane (5% induction; 2–3% maintenance). We then inserted Silastic catheters into the jugular vein, which we passed subcutaneously to the midscapular region and attached to a modified 22-gauge cannula cemented to polypropylene mesh (Sefar). We injected ketoprofen (2.5 mg/kg, s.c., Butler Schein) after surgery to relieve pain and decrease inflammation. We allowed the rats to recover from surgery for 3–4 d. We flushed the catheters daily with sterile saline containing gentamicin (4.25 mg/mL, APP Pharmaceuticals) during the recovery, training, and voluntary abstinence phases.

Drugs

We received (+)-methamphetamine-HCl (methamphetamine) and diacetylmorphine HCl (heroin) dissolved in saline from the NIDA pharmacy. In Experiment 1 we used increasing doses of methamphetamine (from 0.05–0.4 mg/ kg) or heroin (from 0.05–0.1 mg/kg). In Experiments 2–4, we used a unit dose of 0.1 mg/kg for methamphetamine self-administration training based on our previous studies11,12,51,52.

Immunohistochemistry (Experiment 4a)

Immediately after the behavioral tests, we anesthetized the rats with isoflurane and perfused them transcardially with ~ 100 mL of 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4; PBS) followed by ~ 400 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. We removed the brains and postfixed them in 4% PFA for 2 h before transferring them to 30% sucrose in PBS for 48 h at 4 °C. We froze the brains in dry ice and stored them at −80 °C. We cut coronal sections (40 μm) of the prefrontal cortex and amygdala levels using a Leica cryostat. We collected the tissues in cryoprotectant (20% glycerol and 2% DMSO in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4) and stored them at −80 °C until further processing.

We selected a 1-in-4 series of sections from the prefrontal cortex and amygdala levels of each rat at approximate bregma levels of +3.24/+2.76 mm and −1.92/− 2.76 mm, respectively53, and used immunofluorescence to triple-label Fos with PKC and SOM for the amygdala level, and Fos only for the prefrontal cortex level. We rinsed free-floating sections in PBS (3 × 10 min), incubated for 1 h in 10% normal horse serum (NHS) in 0.5% PBS-Tx, and incubated the sections for 48 h at 4 °C with rabbit anti-c-Fos (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, phospho-c-Fos, 5348 S; RRID: AB_10013220), mouse anti-PKCδ primary antibody (1:1,000, BD Biosciences, 610398, RRID:AB_397781), and rat anti-SOM (1:1,000, Millipore, MAB354, RRID:AB_2255365) in 4% BSA in 0.3% PBS-Tx. We rinsed the sections in PBS (3 × 10 min) and incubated them for 4 h with biotinylated donkey anti- rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch, 711–585-152; RRID: AB_2340621), donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch, 715–545-150, RRID: AB_2340846), and donkey anti-rat Alexa Fluor 647 (1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch, 712–605-153, RRID: AB_2340694) in 2% NHS in 0.5% PBS-Tx.

We rinsed the sections three times in PBS (3 × 10 min) and mounted them onto gelatin-coated glass slides, air-dried them, and coverslipped the sections with Mowiol + DAPI (Millipore). We used an EXi Aqua camera (QImaging) attached to a Zeiss Axio Scope Imager M2 using iVision (4.0.15 and 4.5.0, Biovision Technologies) to collect and analyze the images. We captured each image using a 20 × objective. We quantified the total number of cells positive for Fos (white), PKCδ (green) and SOM (red) in the lateral and medial CeA subregions (CeL and CeM). We also quantified the total cells positive for Fos (red) in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), ventral and dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC and dmPFC), lateral and medial orbitofrontal cortex (lOFC and mOFC), anterior insular cortex ventral and dorsal (AIV and AID), and basolateral amygdala (BLA). We performed image-based quantification in a blind manner (mean inter-rater reliability between M.V. and M.Z.: r = 0.89; between M.V. and J.K.H.: r = 0.83; and between M.V. and M.J.: r = 0.80).

RNAscope in situ hybridization assay (Experiment 4b)

We performed RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) as described previously26,40. Briefly, 60 min after the beginning of the test session, we briefly anesthetized the rats with isoflurane (< 30 s) and decapitated them. We rapidly extracted and froze their brains for 20 s in −40 °C isopentane. We stored brains at −80 °C. We then collected CeA coronal sections (16 μm) directly onto Super Frost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). We used RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) and performed ISH assays according to the user manual for fresh-frozen tissue. On the first day, we fixed brain slices in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific) for 20 min at 4 °C. We rinsed the slices three times in PBS and dehydrated the slices in 50, 70, 100, and 100% ethanol. We stored the slices in fresh 100% ethanol overnight at −20 °C. On the second day, we first dried the slides at room temperature (~22° C) for 10 min. To limit the spreading of the solutions, we drew a hydrophobic barrier on slides around brain slices. We then treated the slides with protease solution (pretreatment 4) at room temperature for 20 min and washed it off. We then applied the target probes for Fos, PKCδ, and SOM to the slides and incubated them at 40 °C for 2 h in the HybEZ oven. Each RNAscope target probe contains a mixture of 20 ZZ oligonucleotide probes that bind to the target RNA: Fos-C3 probe (GenBank accession number NM_022197.2; target nt region, 473–1,497); SOM-C1 probe (GenBank accession number NM_012659.1; target nt region, 3–427), and PKCδ-C2 probe (GenBank accession number NM_011103.3; target nt region, 334–1,237). Next, we incubated the slides with preamplifier and amplifier probes (AMP1, 40 °C for 30 min; AMP2, 40 °C for 15 min; AMP3, 40 °C for 30 min). Next, we incubated the slides with fluorescently labeled probes by selecting a specific combination of colors associated with each channel: orange (Alexa Fluor 550 nm), far red (Alexa Fluor 647 nm), and green (Alexa Fluor 488 nm). We used AMP4 AltB to detect triplex Fos, SOM, and PKCδ in far red, red, and green channels, respectively. Finally, we incubated sections for 20 s with DAPI. We washed the slides with one washing buffer twice between incubations. After air-drying the slides, we coverslipped them with a Mowiol fluorescent mounting medium (Millipore). We captured fluorescent images of labeled cells in CeL and CeM, using an EXi Aqua camera (QImaging) attached to a Zeiss AxioImager M.2 microscope using a 20 × objective (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) and used ImageJ software for quantification. We captured each image using a 20 × objective. We quantified the total number of cells positive for PKCδ (green) and SOM (red) in CeL and CeM. We quantified the total Fos cells (white dots surrounding DAPI+ cells in blue). We also quantified the Fos neurons co-labeled with PKCδ or SOM. We performed the image capture and quantification in a blind manner (inter-rater reliability between M.V. and M.Z. r = 0.86).

Self-administration chambers

We trained the rats to self-administer a drug (methamphetamine or heroin) and to gain access to a social peer (social self- administration) in custom-made social self-administration chambers (Fig. 1j and Supplementary Fig. 1). We combined a standard Med Associates self-administration chamber with a custom-made social-partner chamber that was separated by a guillotine door (ENV-010BS). Each chamber had a discriminative stimulus on the right panel (white house-light; Med Associates ENV-215M) that signaled the insertion and subsequent availability of the social reward-paired active (retractable) lever located near the guillotine door and a discriminative stimulus on the left panel (Med Associates ENV-221M, red lens) that signaled the insertion and subsequent availability of the drug-paired active (retractable) lever located on the left side. The levers were located 6 cm above the grid floors and a white cue light (Med Associates ENV-221M, white lens) located above the drug-paired lever and a tone cue (Med Associates ENV-223AM) above the social-paired lever. We also trained rats to self-administer palatable food pellets and drugs in standard Med Associates chambers, as described previously12,26,31,40. The right panel of the chamber had a discriminative stimulus (white house-light, Med Associates ENV-215M) that signaled the insertion and subsequent availability of the food-paired active (retractable) lever; this side also had a pellet dispenser, pellet receptacle, an inactive (stationary) lever, and a tone cue located above the food- paired lever. The left side of the chamber was identical to that described above for the custom-made social self-administration chamber.

Procedures

Social self-administration. We trained rats to self-administer for access to the social partner during daily 40-min (Experiments 1b, 2, and 3) or 120-min (Experiments 1a, 4, and 5) sessions, using a discrete trial design. In Experiments 1, 4, and 5, the resident rats were previously housed with their social partners (cage- mates) until 1 week before social interaction self-administration, and each resident rat only self-administered for their previously-paired partner. In Experiments 2 and 3, the resident rat was paired with an unfamiliar rat who became their social partner on the first day of social interaction self-administration. Each 40 or 120-min daily session included 20 or 60 120-s trials. The trials started with the illumination of the social-paired house-light followed 10 s later by the insertion of the social-paired active lever; we allowed the resident rat a maximum of 60 s to press the active lever on a fixed-ratio-1 (FR1) reinforcement schedule before the lever automatically retracted and the house-light turned off. Successful lever presses resulted in the retraction of the active lever, followed by a discrete 20-s tone cue (Med Associates ENV-223AM) and the opening of the mechanical, guillotine- style sliding door. The resident rat was subsequently allowed to interact with the social partner for 60 s until the house-light turned off, at which point we manually replaced both rats in their appropriate chambers. We recorded the number of successful trials and inactive lever presses.

Drug self-administration

On each training day, we trained rats to self-administer methamphetamine (Experiments 1a, 3–5) or heroin (Experiment 1b) during six 1-h sessions that were separated by 10-min off periods, under an FR1 20-s timeout- reinforcement schedule. To prevent overdose, we limited the number of infusions to 15 per h. We started the self-administration sessions at the onset of the dark cycle; sessions began with the presentation of the red light and 10 s later with the insertion of the drug-paired active lever; the red light remained on for the duration of the session and served as a discriminative stimulus for drug availability. At the end of each 1-h session, the red light was turned off, and the active lever was retracted.

In Experiment 2, we trained rats to self-administer methamphetamine during three 40-min daily sessions that were separated by 15-min off periods, during which the active lever was not retracted; during the off period, we recorded the number of non-reinforced active lever presses. We trained these rats under a fixed-ratio 40-s timeout reinforcement schedule using an FR1 schedule for the first 6 d, FR3 for the next 5 d, and FR5 for the remaining 39 d22.

In Experiment 3, we first trained rats to self-administer methamphetamine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion) using the extended-access escalation model27 (6 h/d, 9 d, FR1 20-s timeout reinforcement schedule). Next, we trained the rats to self-administer the drug for 9 d using the intermittent-access model23. The rats had access to methamphetamine (0.1 mg/kg/infusion, FR1 20-s timeout-reinforcement schedule) during 12 daily 5-min sessions (ON period) that were separated by 25 min OFF periods. During the ON period, the house-light was turned on and the active lever was extended. During the OFF period, the house-light was turned off and the lever retracted.

Food self-administration

Our training procedure is like that described elsewhere12,26,31,40. Briefly, we trained the rats to lever press for food during six 1-h daily sessions that were separated by 10 min under an FR1, 20-s timeout- reinforcement schedule, which led to the delivery of five 45-mg ‘preferred’ or palatable food pellets (TestDiet, Catalogue # 1811155, 12.7% fat, 66.7% carbohydrate, and 20.6% protein)54; pellet deliveries were paired with the 20-s discrete tone cue and the five pellets were delivered 1 s apart. Prior to the first one or two formal operant self-administration training sessions, we gave the rats 1-h magazine training sessions, during which five pellets were delivered noncontingently every 5 min. The sessions began with the presentation of the white house-light, followed 10 s later by the insertion of the food-paired active lever; the white house-light remained on for the duration of the session and served as a discriminative stimulus for the palatable food. At the end of the session, the white house-light was turned off and the active lever was retracted. To match the number of discrete cue presentations to that of methamphetamine (see below), we limited the number of food reward deliveries to 15 per h31.

Discrete choice procedure

We conducted the discrete choice sessions using the same parameters (drug dose, length of social interaction, number of palatable food pellets per reward, stimuli associated with the two retractable levers) that we used during the self-administration training. We allowed rats to choose between the social- and drug-paired levers or the palatable food- and drug-paired levers in a discrete-trial choice procedure. We divided each 120-min choice session into 15 discrete trials that were separated by 8 min, as previously described12,26,31,40. Briefly, each choice trial began with the presentation of the discriminative stimuli for social interaction and drug or food and drug, followed 10 s later by the insertion of the levers paired with both rewards. Rats could then select one of the two levers. If the rats responded within 6 min, they only received the reward corresponding with the selected lever. Thus, on a given trial, the rat could earn either reward but not both. Each reward delivery was signaled by the social-, food-, or drug-associated cue, the retraction of both levers, and the extinguishing of both discriminative cues. If a rat failed to respond on either active lever within 6 min, both levers were retracted, and their related discriminative cues were extinguished with no reward delivery. For the social versus drug choice, when the rats chose the social reward, we manually replaced both resident and social partner rats in their appropriate chambers after 60 s of social interaction.

Voluntary abstinence

After the completion of the training phase, we allowed the rats to choose between the drug-paired lever (delivering one infusion), palatable food-paired lever (delivering five pellets), or social interaction-paired lever (60 s) during 15 discrete-choice trials (separated by 8 min) for ten sessions over 14 d, as described above.

Forced abstinence

After the completion of the training phase, we kept the rats in their homecage and handled them 3–4 times per week.

Relapse test

The relapse test in the presence of drug cues consisted of 30-, 60-, or 90- min sessions (see specific experiments). The test session began with the presentation of the red discriminative cue light, followed 10 s later by the insertion of the drug- paired lever; the red light remained on for the duration of the session. Active lever presses during testing, the operational measure of drug seeking in incubation of drug craving and relapse studies34,55,56, resulted in contingent presentations of the light cue previously paired with drug infusions, but not drug delivery. At the end of the session, the active lever retracted, and the house-light was turned off.

Behavioral tests

We conducted all behavioral tests using the same parameters (dose of drug, length of social interaction, number of palatable food pellets per reward, stimuli associated with the two retractable levers) that we used during the discrete choice sessions (For a detailed description of each experiment, see Supplementary Note).

Delay-discounting test (Experiments 1 and 3)

During the delay-discounting sessions, we progressively increased the delay between presses on the social-paired lever and opening the guillotine door, such that we delayed access to social interaction. There was no delay in the delivery of methamphetamine. For each consecutive pair of delay sessions in Experiment 1, we started at 5-s delay, then 15-s delay, and then increased the delay time by 15 s for up to 120 s, followed by a choice session without delay (the data for 5-s delay, which had no effect on choice, are not included in the statistical analysis or shown in the figures). In Experiment 3, we used the mean number of rewards received on the first 3 d of choice (2 × 0-s delay and 1 × 5-s delay) as a baseline measure of choice behavior. In the fourth-choice session we used a 15-s delay, and then increased the delay time of each daily session by 15 s up to 120 s, followed by a final choice session without delay.

Progressive ratio test (Experiments 2–4)

During the progressive ratio sessions, we increased the ratio of responses per rewards or infusions (food pellets/social interactions or drug, respectively) according to the following sequence: 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, 32, 40, 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, etc.)60. The final completed response ratio represents the ‘breaking point’ value.

Devaluation (satiety) test (Experiment 4)

We gave rats extended access to food or their social partner in their homecage for 0, 1, and 3 h, and 1, 3, and 6 d before the food or social interaction versus drug choice sessions.

Statistical analysis

We used factorial ANOVA and t tests using SPSS (IBM, version 25, GLM procedure). When we obtained significant main effects and interaction effects (P < 0.05, two-tailed), we followed them with post hoc tests (Fisher PLSD). Because our multifactorial ANOVA yielded multiple main and interaction effects, we only report significant effects that are critical for data interpretation. We indicate results of post hoc analyses in the figures but do not describe them in the Results section. We indicate P < 0.001 and provide exact P values for results smaller than 0.05 and greater than 0.001. Supplementary Table 1 provides a complete report of the statistical results for the data described in the figures. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications26,31. Data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. Additionally, except for one panel in Supplementary Fig. 5, we do not present the inactive lever data in the figures, because responding on this lever during the relapse tests was very rare (30-min relapse tests: mean of 0.8 to 9.1 per session; 60-min relapse tests: mean of 4.6 to 9.3 per session; 120-min relapse tests: mean of 7.3 to 15.3 per session).

Data availability

Materials, datasets, and protocols are available upon reasonable request to M.V. or Y.S.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Jin, A. Minier Toribio, and O. Lofaro for their help during the experiments. The research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIDA, a fellowship from the NIH Center on Compulsive Behaviors (M.V.), and NARSAD Distinguished Investigator Grant Award (Y.S.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0246-6.

Online Content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, statements of data availability and associated accession codes are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0246-6.

References

- 1.Nestler EJ Epigenetic mechanisms of drug addiction. Neuropharmacology 76 Pt B, 259–268 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everitt BJ & Robbins TW Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1481–1489 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heilig M, Epstein DH, Nader MA & Shaham Y Time to connect: bringing social context into addiction neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 17, 592–599 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Donovan DM & Kivlahan DR Addictive behaviors: etiology and treatment. Annu Rev Psychol 39, 223–252 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardo MT, Neisewander JL & Kelly TH Individual differences and social influences on the neurobehavioral pharmacology of abused drugs. Pharmacol Rev 65, 255–290 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miczek KA, Yap JJ & Covington HE 3rd. Social stress, therapeutics and drug abuse: preclinical models of escalated and depressed intake. Pharmacol Ther 120, 102–128 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nader MA & Banks ML Environmental modulation of drug taking: Nonhuman primate models of cocaine abuse and PET neuroimaging. Neuropharmacology 76 Pt B, 510–517 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stitzer ML, Jones HE, Tuten M & Wong C Community Reinforcement Approach and Contingency Management Interventions for Substance Abuse Handbook of Motivational Counseling: Goal-Based Approaches to Assessment and Intervention with Addiction and Other Problems (eds Cox WM and Klinger E), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK: (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banks ML & Negus SS Insights from preclinical choice models on treating drug addiction. Trends Pharmacol Sci 38, 181–194 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed SH, Lenoir M & Guillem K Neurobiology of addiction versus drug use driven by lack of choice. Curr Opin Neurobiol 23, 581–587 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caprioli D, Zeric T, Thorndike EB & Venniro M Persistent palatable food preference in rats with a history of limited and extended access to methamphetamine self-administration. Addict Biol 20, 913–926 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venniro M, Zhang M, Shaham Y & Caprioli D Incubation of Methamphetamine but not Heroin Craving After Voluntary Abstinence in Male and Female Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 1126–1135 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed SH Trying to make sense of rodents’ drug choice behavior. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azrin NH, et al. Follow-up results of supportive versus behavioral therapy for illicit drug use. Behav Res Ther 34, 41–46 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanderschuren LJ, Achterberg EJ & Trezza V The neurobiology of social play and its rewarding value in rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 70, 86–105 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solinas M, Chauvet C, Thiriet N, El Rawas R & Jaber M Reversal of cocaine addiction by environmental enrichment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 17145–17150 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zlebnik NE & Carroll ME Prevention of the incubation of cocaine seeking by aerobic exercise in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232, 3507–3513 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith MA Peer influences on drug self-administration: social facilitation and social inhibition of cocaine intake in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 224, 81–90 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strickland JC & Smith MA The effects of social contact on drug use: behavioral mechanisms controlling drug intake. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 22, 23–34 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zernig G, Kummer KK & Prast JM Dyadic social interaction as an alternative reward to cocaine. Front Psychiatry 4, 100 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fritz M, et al. Reversal of cocaine-conditioned place preference and mesocorticolimbic Zif268 expression by social interaction in rats. Addict Biol 16, 273–284 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deroche-Gamonet V, Belin D & Piazza PV Evidence for addiction-like behavior in the rat. Science 305, 1014–1017 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmer BA, Oleson EB & Roberts DC The motivation to self-administer is increased after a history of spiking brain levels of cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 1901–1910 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Zeric T, Kambhampati S, Bossert JM & Shaham Y The central amygdala nucleus is critical for incubation of methamphetamine craving. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 1297–1306 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grundemann J & Luthi A Ensemble coding in amygdala circuits for associative learning. Curr Opin Neurobiol 35, 200–206 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venniro M, et al. The Anterior Insular Cortex-->Central Amygdala Glutamatergic Pathway Is Critical to Relapse after Contingency Management. Neuron 96, 414–427 e418 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed SH & Koob GF Transition from moderate to excessive drug intake: change in hedonic set point. Science 282, 298–300 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piazza PV & Deroche-Gamonet V A multistep general theory of transition to addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 229, 387–413 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawa AB, Bentzley BS & Robinson TE Less is more: prolonged intermittent access cocaine self-administration produces incentive-sensitization and addiction-like behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233, 3587–3602 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimm JW, Hope BT, Wise RA & Shaham Y Neuroadaptation. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature 412, 141–142 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caprioli D, et al. Effect of the Novel Positive Allosteric Modulator of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 2 AZD8529 on Incubation of Methamphetamine Craving After Prolonged Voluntary Abstinence in a Rat Model. Biol Psychiatry 78, 463–473 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong Y, Taylor JR, Wolf ME & Shaham Y Circuit and synaptic plasticity mechanisms of drug relapse. J Neurosci 37, 10867–10876 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balleine BW & Dickinson A Goal-directed instrumental action: contingency and incentive learning and their cortical substrates. Neuropharmacology 37, 407–419 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickens CL, et al. Neurobiology of the incubation of drug craving. Trends Neurosci 34, 411–420 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, Zhang X, Muralidhar S, LeBlanc SA & Tonegawa S Basolateral to central amygdala neural circuits for appetitive behaviors. Neuron 93, 1464–1479 e1465 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bossert JM, Marchant NJ, Calu DJ & Shaham Y The reinstatement model of drug relapse: recent neurobiological findings, emerging research topics, and translational research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 229, 453–476 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solinas M, Thiriet N, Chauvet C & Jaber M Prevention and treatment of drug addiction by environmental enrichment. Prog Neurobiol 92, 572–592 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Augier E, et al. A molecular mechanism for choosing alcohol over an alternative reward. Science 22, 1321–1326 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wise RA & Koob GF The development and maintenance of drug addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 254–262 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caprioli D, et al. Role of Dorsomedial Striatum Neuronal Ensembles in Incubation of Methamphetamine Craving after Voluntary Abstinence. J Neurosci 37, 1014–1027 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thiel KJ, et al. Environmental enrichment counters cocaine abstinence-induced stress and brain reactivity to cocaine cues but fails to prevent the incubation effect. Addict Biol 17, 365–377 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chauvet C, Goldberg SR, Jaber M & Solinas M Effects of environmental enrichment on the incubation of cocaine craving. Neuropharmacology 63, 635–641 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoenbaum G, Chang CY, Lucantonio F & Takahashi YK Thinking outside the box: Orbitofrontal cortex, imagination, and how we can treat addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 2966–2976 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heyman GM Addiction and choice: theory and new data. Front Psychiatry 4, 31 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waldorf D, Reinarman C & Murphy S Cocaine changes: The experience of using and quitting (Temple University Press, Philadelphia, 1991). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Monterosso J & Ainslie G The behavioral economics of will in recovery from addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend 90 Suppl 1, S100–111 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tourigny SC Some new dying trick: African American youths “choosing” HIV/AIDS. Qualitative Health Res 8, 149–167 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Higgins ST, et al. Community reinforcement therapy for cocaine-dependent outpatients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60, 1043–1052 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lash SJ, Burden JL, Monteleone BR & Lehmann LP Social reinforcement of substance abuse treatment aftercare participation: Impact on outcome. Addict Behav 29, 337–342 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Insel TR Digital phenotyping: technology for a new science of behavior. JAMA 318, 1215–1216 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Theberge FR, et al. Effect of chronic delivery of the Toll-like receptor 4 antagonist (+)-naltrexone on incubation of heroin craving. Biol Psychiatry 73, 729–737 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li X, et al. Incubation of methamphetamine craving is associated with selective increases in expression of Bdnf and trkb, glutamate receptors, and epigenetic enzymes in cue-activated fos-expressing dorsal striatal neurons. J Neurosci 35, 8232–8244 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paxinos G & Watson C The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Sixth edition. (Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Calu DJ, Chen YW, Kawa AB, Nair SG & Shaham Y The use of the reinstatement model to study relapse to palatable food seeking during dieting. Neuropharmacology 76 Pt B, 395–406 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Venniro M, Caprioli D & Shaham Y Animal models of drug relapse and craving: From drug priming-induced reinstatement to incubation of craving after voluntary abstinence. Prog Brain Res 224, 25–52 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolf ME Synaptic mechanisms underlying persistent cocaine craving. Nat Rev Neurosci 17, 351–365 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krasnova IN, et al. Incubation of methamphetamine and palatable food craving after punishment-induced abstinence. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 2008–2016 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marchant NJ, Khuc TN, Pickens CL, Bonci A & Shaham Y Context-induced relapse to alcohol seeking after punishment in a rat model. Biol Psychiatry 73, 256–262 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pelloux Y, et al. Context-induced relapse to cocaine seeking after punishment-imposed abstinence is associated with activation of cortical and subcortical brain regions. Addict Biol 23, 699–712 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richardson NR & Roberts DC Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods 66, 1–11 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Materials, datasets, and protocols are available upon reasonable request to M.V. or Y.S.