Abstract

A hallmark of herpesviruses is a lifelong persistent infection, which often leads to diseases upon immune suppression of infected host. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), is etiologically linked to the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and Multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD). In order to establish a persistent infection, KSHV dedicates a large portion of its genomic information to sabotage almost every aspect of host immune system. Thus, understanding the interplay between KSHV and the host immune system is important in not only unraveling the complexities of viral persistence and pathogenesis, but also discovering novel therapeutic targets. This review summarizes current knowledge of host immune evasion strategies of KSHV and their contributions to KSHV-associated diseases.

Keywords: Immune evasion, KSHV, Gammaherpesviruses

1. Introduction

KSHV, the most recent addition to DNA tumor viruses, was initially discovered from the Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) lesion of an AIDS patient in 1994 [1]. KS lesions are histologically complex, characterized by the proliferative spindle cells of lymphatic endothelial origin, a variable inflammatory infiltrate and neoangiogenesis [2]. There are four distinct epidemiological forms of KS: classic KS (sporadic), African KS (endemic), HIV-associated KS (epidemic), and immunosupression-associated KS (iatrogenic). Despite their different environmental and immunological background, the development of each depends upon infection with KSHV [1–4]. In addition to KS, the virus is tightly associated with several lymphoproliferative disorders, including primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and most forms of multi-centric Castleman’s disease (MCD), which are of B cell origin [5,6].

KSHV is a γ2-herpesvirus, with a genome structure closely related to herpesvirus saimiri (HVS), rhesus monkey rhadinovirus (RRV), and murine gamma herpesvirus 68 (γHV-68 or MHV68) [1,7–11]. As with other γ-herpesviruses, KSHV displays two distinct and alternative life cycles: latent and lytic. A lytic replication expresses virtually the entire viral genes and produces new virions, in the course of which the host cell dies; a latent replication, however, expresses only a restricted set of viral genes to allow virus to persist in a dormant state for the lifetime of host. Whereas latency is a default program by KSHV in the majority of infected cells, selective lytic replication is observed in a small proportion of KSHV-infected cells. Viral proteins expressed during both the latent and lytic phase contribute significantly, albeit differently, to the KSHV-associated pathogenesis [2].

While KSHV directly contributes to tumorogenesis, the immune system plays a pivotal role in determining the clinical outcome of KSHV-associated diseases, as demonstrated by the increased replication and enhanced malignant progression in immunosuppressed individuals, in particular in AIDS patients and transplant recipients. However, in immunocompetent individual, virus is not eradicated, rather persists lifelong, suggesting a certain equilibrium between virus and host immune system. Crucial to the ability of the virus to establish a persistent viral reservoir is an evasion of host immune recognition and attack that would otherwise eliminate the virus. As a sophisticated oncogenic virus, KSHV has evolved to possess a formidable repertoire of potent mechanisms for either outwitting or adopting the host’s immune responses, the sum of which contributes substantially to the incidence of KSHV-related malignancies and their resistance to immune control. Almost 50% of KSHV genome is dedicated to modulating host immune response. Intriguingly, most of these viral immune modulators carry the transforming potential and seem to be pirated from the host as native forms or homologues of host proteins to avoid being targeted by a particular arm of the immune system. This review describes an outline of the molecular aspects for KSHV-associated immune evasion and its relevance to the oncogenicity of KSHV.

2. Immune evasion in the KSHV latency program

The long-term latency in lymphoid cells is a trademark of γ-herpesviruses, where virus restricts gene expression to minimize its exposure to host immune system. Furthermore, the latently expressed viral products are believed to be necessary for malignant transformation [12], as exemplified by three latent proteins of KSHV: the ‘latency-associated nuclear antigen’ (LANA), viral cyclin (v-cyclin), and viral Fas-associated death domain (FADD) interleukin-1B-converting enzyme (FLICE) inhibitory protein (vFLIP), also referred to as the KSHV ‘oncogenic cluster’. These three genes share the same set of transcript, suggesting their coordinated expression during viral latency. Other viral genes expressed during latency include Kaposin, viral IRF3 (in PEL) and the recently identified KSHV microRNA cluster.

2.1. LANA

LANA is best characterized as a viral latent protein that is essential for establishing and maintaining KSHV latency in proliferating cells, therefore contributing to the latent signature of KSHV infection. LANA tethers the viral episome (circular DNA) to the host chromosomes during mitosis, ensuring right partitioning of the viral genome into progeny cells [13]. Moreover, it blocks the expression of the reactivation transcriptional activator (RTA), a master switch from latency to lytic reactivation, thus keeps a lytic replication in check [14]. However, consistent expression of LANA in latently infected cells creates a potential target for the immune recognition. As seen with its functional equivalents in the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and MHV68 [15,16], LANA regulates its own translation and degradation to minimize antigen processing, allowing LANA-producing cells to escape the recognition of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [17]. Apart from its role in latency control, LANA also possesses oncogenic properties. It interferes with tumor suppressor functions of p53 and retinoblastoma protein (Rb) [18,19], and transforms primary rat embryo fibroblasts with the cellular oncogene Hras [19]. Furthermore, by nuclear sequestration of the glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β, an important modulator of the Wnt signaling pathway, LANA promotes cellular accumulation of β-catenin and subsequent upregulation of TCF/LEF-regulated genes involved in cell differentiation [20]. Recently, LANA is shown to suppress TGF-β type II receptor through epigenetic silencing, which blocks TGF-β signaling, and thereby contribute in part to the establishment and progression of KSHV-associated neoplasia [21].

2.2. v-cyclin

KSHV v-cyclin is a homolog of cellular D-type cyclins [22]. However, unlike its cellular counterpart, v-cyclin shows a broader spectrum of substrate specificity in concert with the cellular cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) 6, and is less sensitive to cellular cdk inhibitors [23,24]. When overexpressed in transfected cells, v-cyclin drives aberrant cell cycle progression, which leads to activation of DNA damage response and chromosome instability [25]. As a result, v-cyclin, when expressed in primary cells, induces p53-dependent growth arrest [26]; however, in the absence of p53, v-cyclin confers lymphomas in v-cyclin transgenic mice [27]. This highlights the importance of p53 in KSHV-infected lymphoma. Indeed, the reactivation of p53 by a small-molecule MDM2 inhibitor, Nutlin-3a, induces killing of KSHV-infected cells [28].

2.3. vFLIP

Based on its homology to caspase 8/FLICE, K13 of KSHV was originally designated as a vFLIP (viral FLICE inhibitory protein) with two homologous copies of a death effector domain. Although it is initially shown to act as an inhibitor of caspase 8, in a similar fashion to its cellular homolog, and protect in vitro virally infected cells against Fas-mediated apoptosis [29]. However, this finding was not confirmed in vFLIP transgenic mice [30]. Instead, vFLIP is now generally believed to be a potent activator of the NF-κB pathway [31–33]. In support of this notion, vFLIP transgenic mice displayed constitutive NF-κB activation, enhanced lymphocyte proliferation and increased incidence of lymphoma [34], which is independent of inhibition of Fas-induced apoptosis [30,33,35,36]. In line with this, silencing vFLIP expression or pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB triggers apoptosis of PEL cells and inhibits tumor growth in a PEL mouse model [37]. Intriguingly, in primary endothelial cells, vFLIP induces cell spindling, a characteristic of KS lesion, which reflects cytoskeleton reorganization and is also linked to NFκB activation [38]. Furthermore, vFLIP expression is found to induce NF-κB-regulated cytokines expression and secretion and likely contributes to building inflammatory microenvironments of KS [38,39]. Apart from its role in cell survival and morphology change, it has recently been reported that vFLIP-mediated NF-κB activation inhibits lytic replication by blocking RTA expression and activity, as seen with LANA [40]; however, this effect of vFLIP may be cellular context dependent [41]. Nevertheless, taken together, as a result of its strong activation of the NF-κB signaling, vFLIP plays a plethora of roles in viral cell survival, transformation, morphological change, inflammatory activation, and latency control, thereof directly contributes to KSHV pathogenesis. Other than vFLIP, KSHV proteins such as vGPCR, K1, K15, and vIL-6 have all been implicated in regulating NF-κB activity, suggesting a critical role of NF-κB signaling in viral pathogenesis.

2.4. Kaposin B

Kaposin B is transcribed from the kaposi locus, which contains orf12 preceded by two direct repeats (DR2 and DR1). Although expressed during latency, transcription of the kaposin locus is strongly induced during lytic replication by RTA [42]. The complex translational program of the kaposi locus generates at least three protein species (kaposin A, B and C), of which kaposin B is the predominant product and consists of DRs alone. The pivotal role of kaposin B in KSHV pathogenesis resides in its post-transcriptional regulation of cytokine production [43]. Kaposin B directly binds to and activates cellular MAPK-associated protein kinase 2 (MK2), a central modulator of cytokine mRNA stability, through DR2 repeat. Consistent with this, kaposin B expression blocks the degradation of AU-rich element (ARE)-containing cytokine mRNAs and ultimately increases cytokine release such as IL-6, which drives proliferation and tumor formation. The activation mechanism of kaposin B on MK2 has yet to be elucidated [44]. Nevertheless, this study represents a striking example of post-transcriptional regulation of host gene expression by the viral protein.

2.5. MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

miRNAs are small noncoding RNAs (~22 nucleotides long) that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression through miRNA-mRNA crosstalk, to induce degradation and/or translational repression of targeted mRNAs [45]. Due to the sequence-specific regulation and non-immunogenic properties of miRNA, it is not surprising that viruses may adapt this strategy to optimize the cellular environment for viral infection and pathogenesis [45]. This is particular true for the oncogenic herpesviruses, which insofar as have been shown to encode the most abundant miRNAs. For instance, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) encodes at least 11 miRNAs, while 23 miRNAs have been identified in EBV thus far [46]. KSHV has been reported to encode a cluster of 12 miRNAs, all of which are surprisingly nestled within the latency-associated locus of the KSHV genome that encodes LANA, v-cyclin, v-FLIP, and kaposin and is highly active in gene expression in all forms of KSHV-associated malignancy [47–49]. Although the regulatory targets of the majority of KSHV miRNAs are unknown, the miRNA-k12–11 of KSHV has recently been shown to mimic host miRNA-155 [50–52], an oncogenic miRNA important for lymphocyte differentiation and immunity. When overexpressed, both miRNA-k12–11 and miRNA-155 downregulate the expression of a common set of target genes such as BACH-1, a transcriptional repressor involved in hypoxia response, which may contribute to KSHV-associated pathogenesis [47–49]. This finding thus suggests that in addition to protein-based strategy, host miRNA-mediated gene regulation can be ‘hijacked’ or subverted by KSHV (as well as other herpesviruses) for viral immune evasion and/or viral induced oncogenesis; the detail of which, however, needs to be further investigated.

Although the latency program of KSHV has long been thought to drive KSHV-associated pathogenesis, the recent discoveries that the KSHV latency program per se does not appear to have a strong immortalizing activity in vitro, nor does it initiate endothelial cell transformation in vivo [53,54], lead to the concern that KSHV latent genes may not suffice to initiate tumorigenesis. In contrast, viral lytically expressed products are implicated to underlie certain clinicopathological features of KSHV-associated diseases [55,56], indicating that lytic replication may be not only important for viral propagation, but also critical for viral pathogenicity [2]. In fact, the majority of viral lytically expressed proteins are potent immunomodulator of both innate and adaptive immunity, suggesting viral immune evasion is intimately linked to KSHV tumorigenesis, thus represents potential therapeutic target for KSHV-associated diseases.

3. KSHV strategies for immune evasion

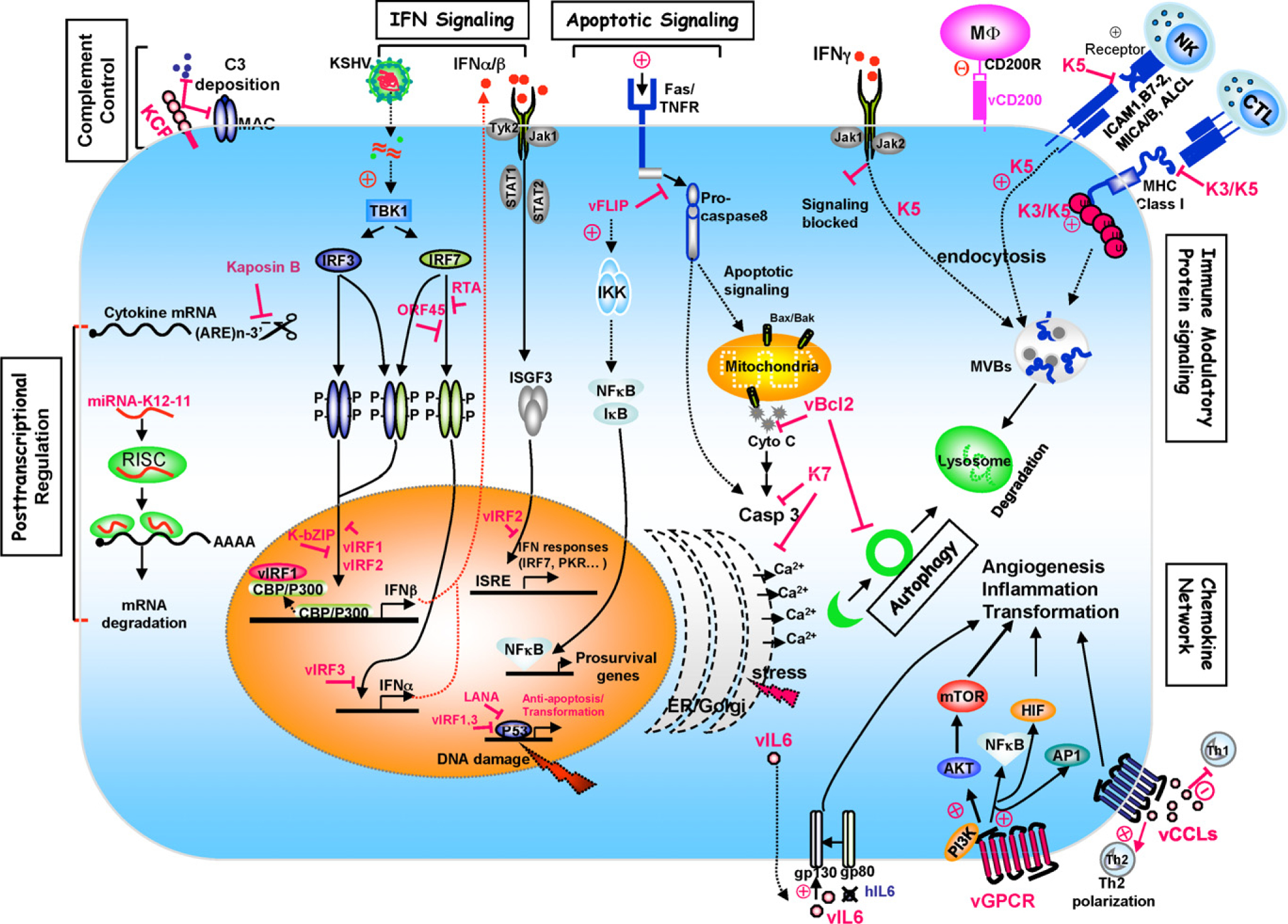

The immune evasion strategies of KSHV in the context of host innate and adaptive immunity include: interference with interferon (IFN) signaling, alteration of host chemokine network; inhibition of complement control; blockage of apoptotic and autophagic pathways; and escape from natural killer (NK) cell lysis and cytotoxic T cell (CTL) response. Notably, these viral innate and adaptive immune evasions are coordinately linked. A case in point is that KSHV cytokine homologs blunt antiviral T helper 1 (Th1) response by polarizing T helper 2 (Th2) response and thus upset the home-ostatic balance of humoral and cell-mediated immunity. All in all, these evasion strategies ensure persistent infection and spread of KSHV, and contribute to the pathogenesis of KSHV-associated diseases.

3.1. Interference with interferon (IFN) signaling

The interferons (IFNs) are a large group of secreted cytokines dedicated to coordinate immunity to viruses and other pathogens (reviewed in [57–60]), and also involved in cell growth, differentiation, and immuno-regulatory activities. At least three distinct types of IFNs have been classified as type I IFNs (IFN-α/β), type II IFN (IFN-γ) and type III IFNs [IFN-λ1, -λ2, and -λ3 (also known as interleukin-29 [IL-29], IL-28A, and IL-28B, respectively)]. IFN-α/β are produced in direct response to viral infection in nearly every cell type, and is transcriptionally controlled by the cellular IFN regulatory factors (IRFs) (reviewed in [58,59,61]). The IRF family is characterized by a well-conserved N-terminal DNA binding domain (DBD) that possesses five conserved tryptophan repeats. Among nine hitherto identified members (IRF-1 to IRF-9) of the IRF family, IRF-3 and IRF-7 are the key regulators of the IFN-α/β gene expression elicited by viral infection. Unlike IRF3, IRF7 expression in most cells is low but is strongly induced by type I IFN-mediated signaling, leading to the concern that IFN-α/β gene induction occurs sequentially [58]. Upon viral infection, cytoplasmic IRF3 undergoes serine phosphorylation of its C terminus, followed by dimerization and nuclear translocation, whereby it complexes with the transcriptional co-activator histone transacetylases CBP/p300 and directly induces the expression of IFN-β [62]. The initial IFN-β induction (first phase) stimulates type I IFN receptor in both autocrine and paracrine fashions, leading to the induction of IRF7 gene that in turn can efficiently activates both IFN-α and IFN-β genes (second phase), thus making a postive-feedback loop operational [58]. The large set of genes induced by IFN-α/β ultimately establish the “antiviral state” in host cells to suppress the viral replication and spread [63–65]. Undoubtedly, viruses have evolved various strategies to circumvent IFN response [57,66–68]. In the case of KSHV, IRF3-and/or IRF7-mediated transcription gain most viral attention for immune evasion.

3.1.1. Selective inhibition of IRF3-, IRF7-mediated transcription

KSHV-modulated IFN evasion is particularly ascribed to its encoding of four viral homologues of IRFs (vIRF1–4), all of which are expressed during lytic reactivation [8,9], yet vIRF1 and vIRF3/latency-associated nuclear antigen 2 (LANA2) transcripts are also detected in latently infected cells [69–71]. The importance of this differential expression of vIRFs is not yet known, but this observation suggests that these vIRFs may function redundantly, but act differentially depending on the nature of the cell type and the stage of viral infection, thereby eliciting distinct IFN evasion [72].

vIRFs of KSHV share homology in their N-terminal region to the DBD of host IRFs, but lack several of tryptophan residues essential for DNA binding, and thus, in contrast to cellular IRFs, are presumably defective in DNA binding [73]. Three of the four vIRFs (vIRF1–3) have been functionally characterized and shown to inhibit the induction of type I IFN genes and IFN-stimulated genes (ISG) in infected cells and function as dominant inhibitors of the cellular IRFs, albeit with different mechanisms. KSHV-encoded vIRF1 is the first viral IRF-family member discovered to effectively repress cellular IFN response [74,75]. Unlike its cellular homologue, vIRF1 does not bind DNA; instead, it directly targets p300 transcriptional co-activator [76–78]. The association of vIRF1 with p300 interferes with the p300-IRF3 complex formation and p300 histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity in vitro, which as a result prevents IRF3-mediated transcriptional activation [77]. However, the efficacy of vIRF1 to block IFN response is challenged by the short half-life and duration of vIRF1 in KSHV-infected cells [79], raising the concern that vIRF1 might function at vulnerable stages of viral replication and/or other vIRFs and viral immunomodulators are required to confer complete inhibition. Similarly, full-length vIRF2 is found to inhibit the expression of IFN-inducible genes driven by IRF1, IRF3 and IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3), but not by IRF7. The underlining mechanism, however, is yet to be defined, but it is less likely through p300 sequestration or IRF3 binding as shown on vIRF1 [80]. Unlike vIRF1 and vIRF2 that mainly target IRF3-mediated IFN signaling, vIRF3 specifically interacts with IRF7 and this interaction inhibits IRF7 DNA-binding activity, thereof abrogates IFN-α production and IFN-mediated immunity [81]. Although its precise mechanism has not been elucidated, it is thus of interest to speculate that vIRF4 of KSHV may also interfere with certain host IRFs to compromise antiviral immunity.

The apparent importance to KSHV of the ability to modulate IRF7 activity is evident from the observation that the two immediate-early lytic proteins of KSHV, ORF45 and RTA, also negatively regulates IRF7, by preventing its phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, and by promoting its ubiquitination for proteasome-mediated degradation, respectively [82–84]. Furthermore, it has been recently reported that K-bZIP, a leucine zipper-containing transcription factor encoded by KSHV ORFK8, binds specifically to the IFN-β promoter, and in so doing, hinders the DNA binding of IRF3 and thus precludes IFN production and signaling [85]. The fact that KSHV has evolved derivatives of IRFs to interfere with IFN response underscores the importance of this process in antiviral defense and highlights the virus–host coevolution.

3.1.2. Oncogenic potential of vIRFs

In addition to the immune modulation activity, cellular IRFs are getting recognized to play a crucial role in the control of cell growth, cell survival, differentiation, and regulation of oncogenesis (reviewed in [73]). For instance, IRF1 and IRF5 both possess tumor suppressor activity, and the expression of IRF4 and IRF8 antagonize the development of leukemia. On the contrary, IRF2 and IRF4 display oncogenic activities such that overexpression of IRF2 in NIH3T3 cells causes oncogenic transformation, and the expression of IRF4 is induced in human T cell lymphoma. The cooperative and antagonized relationships between IRF family members reflects a ‘balancing act’ in host immune control and tumor suppression, which conceivably can be disturbed by viruses to their ends for persistent infection and pathogenesis.

As seen with the cellular IRF2 proto-oncogene [86], KSHV vIRF-1 induces cell growth transformation [87,88]. When the vIRF-1 gene was stably expressed in NIH 3T3 cells, the cells became transformed and displayed enhanced fibrosarcoma in nude mice. This transformed phenotype of vIRF-1 is presumably mediated in part by interfering with the tumor suppressor p53 function through two coordinated mechanisms [77]. On one hand, the vIRF1 directly associates with p53, suppresses the level of phosporylation and acetylation of p53, and inhibits the transcription and pro-apoptotic activities of p53 [87,88]. On the other hand, vIRF1 directly targets and inhibits the upstream ATM kinase activity to further deregulates p53 stability [89]. The synergistic effects of vIRF1 on p53 and ATM may thus circumvent host growth surveillance and facilitate viral replication in infected cells. Further evidence in support of the oncogenic property of vIRF1 is that vIRF1 binds to and inhibits the activities of cell death regulator GRIM19 and Smad3/Smad4 transcriptional proteins in TGF-β signaling, as well as down-regulates CD95L expression [90,91]. In spite of its many repressive activities as described, vIRF1 acts as a transcriptional activator to induce the vIL-6 and c-myc gene [77]. vIRF2, however, does not share with vIRF1 the activity in cell growth transformation [80], although the first exon of vIRF2 was shown to inhibit apoptosis through transcriptionally suppression of CD95L expression in activated T cell [90]. Unlike other vIRFs, vIRF3 of KSHV is a B cell-specific latently expressed nuclear protein that inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis [70] and PKR-induced activation of caspase-3 in vitro, thereby promotes survival of the latently infected cells [92]. However, vIRF3 is also found, in striking contrast, to induce apoptosis by inhibition of NF-κB activity [93]. This discrepancy, possibly due to different cell systems used and the biased effects of gene overexpression, has recently been resolved by using RNAi-mediated silencing of vIRF-3 in naturally infected PEL cells [94]. It clearly shows that knockdown of vIRF-3 decreases cell proliferation and enhances apoptosis in both EBV+ and EBV− PEL cells, suggesting the oncogenic property of vIRF-3 and its potential role in KSHV-associated lymphomagenesis. Although the molecular details of vIRFs-mediated oncogenesis has yet to be confirmed, the dedication of vIRFs in both viral immune evasion and cell proliferation suggests these two processes are tightly linked and likely coordinately regulated, making vIRFs attractive therapeutic targets for KSHV infection control.

3.2. Alteration of the chemokine network

Viral infection stimulates the production of cytokines and chemokines that initiate the activation and migration of immune cells to the sites of infection, with a role to play in lymphocyte development and differentiation, in angiogenesis, and in anti-viral defense [95,96]. The large set of chemokine family can be divided into four subfamilies (CC-, CXC-, C- and CX3C-) on the basis of the relative positions of two N-terminal cysteine residues. Their activities are mainly mediated through binding to their cognate receptor, ‘seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)’, to elicit chemotaxis [97]. Many viruses, particularly herpesviruses and poxviruses, utilize a variety of methods to modulate the chemokine machinery by encoding their own version of chemokines (virokines) or chemokine receptors (viroceptors), or by secreting chemokine-binding proteins (vCKBPs), that are presumed to assist viral escape of host immune recognition and attack [98,99]. In view of immune evasion strategies, viral mimicry of chemokine and their receptors have a preference for specific inhibitory mechanism or they can re-direct the outcome of the immune response for the advantage of viral replication. Alternatively, viruses can hijack chemokine pathways to induce cell proliferation or migration for viral pathogenesis. Furthermore, certain chemokine receptors can be subverted for facilitating viral entry, for example, HIV utilizes chemokine receptors (CXCR4 and CCR5) for entry into susceptible cells [100].

3.2.1. Virally encoded chemokines (vCCL-1, vCCL-2, vCCL-3)

KSHV encodes three viral CC- class chemokine homologs termed vCCL1 (ORF K6), vCCL2 (ORF K4), and vCCL3 (ORF K4.1), formerly known as vMIP-I, vMIP-II and vMIP-III, respectively. These virokines function as agonist and/or antagonist against selective host chemokine receptors to maneuver the viral induced lymphocyte profile for immune evasion. For instance, vCCL1 acts as an agonist of CCR8, whilst vCCL3 selectively agonizes CCR4 [101–103]. vCCL2 is also shown to be a unique agonist towards CCR3 [101]. Interestingly, each of these agonized chemokine receptors are preferentially expressed on Th2 cells, but not on Th1 cells, suggesting the potential of vCCLs as the Th2 lymphocyte chemoattractants [104]. Meanwhile, vCCL2 appears to be a potent immunosuppressor by binding and antagonizing a broad spectrum of host CC, CXC and CX3C- chemokine receptors commonly found on Th1 cells [101,102,105,106]. Consistent with this notion, vCCL2 effectively blocks the RANTES-induced arrest of monocytes and Th1 cells under flow condition in vitro [107]; administration of vCCL2 significantly attenuated leukocyte infiltration and tissue damage in a rat model of glomerulonephritis [108]. Concerning its binding to CXCR4 and CCR5 that are the two major coreceptors of HIV, vCCL2 is shown to prevent infection of HIV on CD4+ cells in vitro by competing with the virus for the coreceptors binding [101].

The selective chemotactic activity of vCCLs correlates with the presence of predominant Th2 lymphocyte infiltrates in KS lesions [109]. Th2 cells mainly secrete cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-5 to promote humoral immunity, while Th1 cells predominantly release cytokines such as lymphotoxin and IFN-γ to promote cellular immune responses [110]. Therefore, by chemoattracting Th2 rather than Th1 lymphocytes preferentially to the site of infection, the vCCLs deviate host immune response away from an undesirable cell-mediated immune responses to a more favorable antibody predominant Th2 microenvironment, thereby facilitating evasion from cytotoxic reactions [107,109]. Th2 polarization was also observed in EBV, CMV, murine CMV, and poxviruses, suggesting that this may represent a generalized viral strategy for dampening host immune response [111–113].

Apart from their respective immunomodulatory roles, vCCLs all display angiogenic properties when applied to the chorioalantonic membrane of chicken eggs even though analogous activities have not been found of their cellular CC chemokines [101,114]. These findings suggest that the expression of vCCLs might account in part for the formation of new blood vessels, the hallmark of KS lesions, in cooperation with other KSHV angiogenic factors such as vGPCR and vIL-6 (discussed below).

3.2.2. Virally encoded chemokines receptor (vGPCR)

ORF74 of KSHV, a “pirated” human chemokine receptor, is a member of the GPCR superfamily and transcribed as an early gene during lytic infection [115]. Compared to other viral or cellular chemokine receptors, vGPCR binds with high affinity to a much broader array of both CXC and CC chemokines [116,117]. However, unlike cellular GPCR, vGPCR is ligand-independent and constitutively active. Along with this finding, the N-terminal extracellular region of vGPCR is shown to be necessary for chemokine binding, but dispensable for its signaling activity [118], whereas the last five amino acids of the cytoplasmic tail of vGPCR is the major determinant for its constitutive activation [119].

Expression of vGPCR is sufficient to induce cellular growth transformation and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis in fibroblasts, suggestive of its oncogenic potential [120]. Transgenic mice expressing vGPCR under either a ubiquitous (SV40) promoter or a T cell-specific (CD2) promoter develop KS-like angioproliferative lesions, further underscoring the biological significance of vGPCR in KSHV-associated disease [121–123]. Nevertheless, a major conundrum is that how a lytic gene of KSHV could be so important in deregulating cell growth. The abortive lytic replication or the dysregulated expression of vGPCR during the latent phase of KSHV infection under certain circumstances perhaps help explain this paradox [124].

Mechanistically, vGPCR is found to constitutively activate a series of transcription factors AP-1, NF-κB, and hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), which, in turn, lead to expression of growth factors, pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as angiogenic factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), IL-1β, IL-8, GRO-α, IL-6, TNF-α and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), all of which are known to be expressed in KS lesions [119,120,123]. VEGF and other factors may act in autocrine and/or paracrine fashion to promote KS pathogenesis [120]. Notably, of the complex intracellular cascades activated by vGPCR, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR cell survival pathway turns to play a central role in vGPCR-induced oncogenesis. By stimulating the PI3K/Akt/TSC cascade, vGPCR activates mTOR through both direct and paracrine mechanisms, which can be pharmacologically inhibited by a mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, [125,126]. Along with this, rapamycin has been clinically used as an effective anticancer agent for KS, which in this context can be explained at least in part as a consequence of antagonizing the effect of vGPCR on the activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. However, the underlining mechanism accounting for the efficacy of rapamycin in KS treatment remains unclear.

Due to the lack of efficient cell culture system and appropriate animal models of KSHV infection, the role of vGPCR in the context of viral infection is limited. vGPCR is conserved in all members of γ−2-herpesviruses such as MHV68, HVS, and RRV [116,127]. Analysis of the vGPCR deletion mutants of MHV68 reveals that vGPCR of γ2-herpesviruses is required for chemokine-stimulated viral replication as well as reactivation from latency, which may represent a novel mechanism by which viruses subvert immune system [128].

3.2.3. vIL-6

Originally identified as a B-cell differentiation factor, interleukin (IL)-6 is a pleiotropic inflammatory cytokine involved in the regulation of the immune response, inflammation, oncogenesis and angiogenesis [129]. Of note, KSHV orf k2 encodes a homolog of human IL-6 (hIL-6), termed vIL-6, which exhibits nearly 25% amino acid identity with hIL-6 and is unique to KSHV [130]. Although expressed primarily as a lytic protein, vIL-6 protein is frequently detected in latently infected PEL cells in the absence of other lytic genes, making it a particularly important cytokine in the KSHV-associated pathogenesis and immune evasion [130–132]. vIL-6 activates the same downstream JAK/STAT and MAPK signaling pathways as its cellular counterpart [133]. In vivo, vIL-6 promotes tumoral angiogenesis by upregulating the expression of VEGF [134]. Despite their similarities in structure and function, vIL-6 differs significantly from hIL-6 in its receptor engagement and utilization [56]. While hIL-6 requires both IL-6R (gp80) and gp130 for intracellular signaling, vIL-6 directly binds and activates gp130, independent of gp80. This property enables vIL-6 to signal more promiscuously than hIL6, even in cells with suppressed surface expression of gp80, such as those exposed to IFN-α, thereby contributing to its role in immune evasion. Moreover, IFN-α stimulates vIL-6 expression through the IFN-stimulation response element (ISRE) sequence in its promoter, which in turn further amplifies the vIL-6 signaling pathway by an autocrine or paracrine loop [56]. Of relevance to this finding, the infected PEL cells exhibits reliance on vIL-6- but not hIL-6-mediated signaling.

In spite of gp80-independency, the positive role of gp80 has been discovered for the signaling complex formation and activation of vIL-6, but not hIL-6 [135]. In addition to form a stable tetramer vIL-6/gp130 complex, vIL-6 can also signal via hexameric vIL-6/gp80/gp130 complex with enhanced vIL-6 signaling potency [55]. In fact, gp80 has been found to stabilize gp130 dimerization induced by vIL-6 [136]. Conceivably, vIL-6 may utilize gp80-independent terameric and/or gp80-dependent hexameric complex to elicit distinct signaling activity to adapt to host stress responses against infection.

3.2.4. vCD200 (vOX2)

The ORF K14 of KSHV encodes a viral homolog of CD200 (also known as OX2), an IgG superfamily cell surface molecule that functions in regulating immune responses. CD200 has a broad expression profile, but expression of its receptor (CD200R) is mainly restricted to myeloid lineage cells [137], pointing to the roles for CD200 in regulation of myeloid-derived cells, such as dendritic cells, macrophages and mast cells. As noted, CD200/CD200R interaction delivers an inhibitory signal to cells of the myeloid lineage [138]. Despite its limited homology to its cellular counterpart, vCD200 of KSHV appears to bind the same receptor with identical affinity and kinetics [139]. This binding, as seen with CD200, suppresses macrophage activity and reduces Th1 cell-associated cytokine production in vitro [139]; moreover, administration of vCD200 attenuated inflammatory and immune response in mice [140], suggestive of an immunosuppressive activity for vCD200 in KSHV infection. In fact, homologues of CD200 are also identified in other viruses, such as RRV, CMV and myxoma virus [141–143]. Thus, by pirating CD200 on the surface of infected cell, viruses may transmit an inhibitory signal to macrophages and dendritic cells, reduce their abilities to prime T cells and prevents the immune system from eliminating virus [139,140,144].

Overall, by producing immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g. vCCL2), expressing immunosuppressive molecules on the surface of infected cells (e.g. vCD200), and restricting Th1 cell activity and cytokine production, KSHV infection may skew the intracellular chemokine network, thus negatively regulate immune system. Meanwhile, these viral factors (e.g. vGPCR and vIL6) as indicated, promote cellular proliferation, induce angiogenesis and inflammation, thus providing a favorable microenvironment for viral replication, dissemination and/or pathogenesis.

3.3. Inhibition of complement control

The complement system is long considered to be a key arm of host innate immunity and a mediator between innate and adaptive immune response. It can be activated by three established mechanisms: specific antibody–pathogen binding (classical pathway), surfaces of pathogens (alternative pathway), or recognition of microbial surface carbohydrate by lectins (lectin pathway). All of these activation processes culminate in the assembly of the C3 and C5 convertase complexes, then end in the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) that punches a hole in infected cells or pathogens (for review see [145]). Beside the direct lysis of invading pathogens, deposition of the complement C3b and C4b onto the pathogen surfaces, so-called opsonization, enhances phagocytosis and increases the humoral response to those pathogens [146,147].

To avoid autologous complement attack and/or aberrant activation on host cell, the complement cascade is fine-tuned by a set of soluble and membrane-bound regulatory proteins, referred to as regulators of complement activation (RCA), all of which share a common structural motif, called short consensus repeat (SCR). Two mechanisms are mainly attributed to the RCA-mediated complement inhibition: (i) accelerating decay of C3/C5 convertase (enzymatic complexes that cleave C3/C5 leading to deposition of C3b/C5b on the activating surface) by dissociation of enzyme subunits; (ii) cofactor for the cleavage of C3a or C4b to the inactive fragments by Factor I (reviewed in [148]). Given the potent effects of RCAs in complement control, some viruses including human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), HIV, human T cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV-1) and SIV have subjugated the host RCAs to their own ends for complement evasion by either upregulating RCA expression on host cell surface, recruiting the protective RCA to viral surface and/or incorporating host RCAs into their envelopes during egress process, to protect the virion from the complement-mediated attack [149,150].

All γ2-herpesviruses, including KSHV, HVS, RRV, and MHV68, are equipped to interfere with the complement activation by encoding host RCA homologs [151–153]. The orf4 gene of KSHV encodes three isoforms of a lytic KSHV complement control protein (KCP) generated by alternative splicing. All KCPs possess four N-terminal tandem SCR repeats and have equivalent function in complement inhibition [154–159]. The redundancy of KCPs may ensure the comprehensive control of complementary pathway. KCP has been shown to enhance the decay of the classical C3 convertase, prevent C3b deposition on sensitized cells, and acts as a cofactor for factor I-mediated inactivation of C3b and/or C4b [153–156,160]. Mapping of the functional domains of KCP using SCRs deletion/swapping or antibody blocking showed that SCRs 1 and 2 are required to decay the classical C3 convertase, while all four SCRs are essential for the alternative C3 convertase decay accelerating activity [154,156,158]. Moreover, the minimum region necessary for the factor I cofactor activity is confined to SCRs 2–3 [156]. Notably, KCP has been also shown to express on the surface of KSHV virions and bind heparin through SCR1–2. Pre-incubation of KSHV with a monoclonal anti-KCP antibody targeting heparin-binding site of KCP as well as with soluble KCP reduces KSHV infection. This result suggests that the presence of KCP on the viral surface may not only mediates immune evasion, but also facilitates viral entry by binding to heparin sulfate on the cell surface [156,161]. The importance of complement evasion in γ2-herpesviruses infection was recently underscored in a mouse model of MHV68 infection, in that deleting the viral RCA of MHV68 leads to attenuated infection in wild-type mice, but not in C3-deficient mice [162]. Unlike other γ-herpesviruses, HVS encodes two distinct complement regulatory proteins. The HVS complement control protein homolog (CCPH) shows similar functional activity to those described for KCP, in that it inhibits C3b deposition and C3 convertase activity [151]. A second, encoded by HVS orf15, is a functional homolog of CD59, which tightly binds to C5b-8, blocks the formation of the terminal MAC, and protects cells from the complement-mediated lysis [163]. Thus, viruses have devised multiple strategies to manipulate the complement system, highlighting the importance of complement cascade to their lifecycles.

3.4. Modulation of apoptosis and autophagy

Apoptosis and autophagy, characterized by distinctive morphological and biochemical changes, are both tightly regulated and highly conserved processes essential for homeostasis, development and disease [164–167]. The role of apoptosis as a host defense mechanism against viral infection has been well documented [165]. Whether triggered via internal inducers (intrinsic pathway, mitochondria-dependent) such as viruses or via external stimuli (extrinsic pathway, death receptor-mediated) such as the engagement of TNFαR, apoptosis proceeds through a cascade of internal proteolytic digestion, resulting in a collapse of cellular infrastructure (for review see [168]). Indeed, apoptosis represents a predominant form of virally infected cell demise. In response, viruses have evolved numerous ways of circumventing this. Most DNA viruses including oncogenic KSHV are genetically equipped with the anti-apoptotic ability to ensure viral replication and propagation, which at certain stage of viral life cycle may also influence viral pathogenesis. In contrast to the ‘self-killing’ apoptotic program, cellular autophagy (Greek for “self-eating”) involves the lysosomal degradation and recycling of the cytoplasmic materials delivered by the double-membrane bound vesicle, termed autophagosome. Although historically recognized as a cellular survival program, under certain circumstances, marked regulation of autophagy can mediate cellular death, known as class II programmed cell death (PCD) [164,169]. In keeping with its activities of membrane trafficking and lysosome-dependent degradation, autophagy has been indicated to selectively deliver intracellular bacteria and viruses to lysosomes for removal (a process referred to as xenophagy), or transmit viral nucleic acids and antigens to endo/lysosomal compartments for activation of innate and adaptive immunity (for review see [170]), thereby being recently confirmed as an important intracellular effector of host immunity.

While these two pathways are seemingly independent, apoptosis and autophagy are not mutually exclusive; instead, they are substantially interconnected and coordinately regulated [171–173]. For instance, cellular Bcl-2 (cBcl-2), the prototype apoptosis inhibitor, is recently found to negatively regulate autophagy by binding to Beclin1 autophagic protein [174]. In accords with this finding, vBcl-2s of γ2-herpesviruses including KSHV and MHV68 potently inhibit both apoptosis and autophgy by binding to specific effectors in these pathways, further highlighting the contribution of both pathways in restriction of viral lifecycle and pathology [174,175].

3.4.1. vBcl-2-mediated anti-apoptosis and anti-autophagy

The intrinsic, or mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis is controlled by the B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family proteins, which comprises both pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules [176]. The defining feature of this family is the presence of multiple conserved Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains. The pro-survival cellular Bcl-2 proteins (e.g. Bcl-2, Bcl-xL) have been previously shown to block apoptotic cell death by binding to and inactivating pro-death Bcl-2 family molecules such as BAX, BAK or BAD, which otherwise disrupt the outer mitochondrial membrane integrity and promote cytochrome c release [177]. Recently, the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 is also found to directly bind autophagy protein Beclin1 and inhibits stress-induced autophagic cell death, which to certain extent may contribute to Bcl-2-mediated oncogenesis [174,178]. Given the potent death-inhibitory effects of Bcl-2, all members of γ-herpesviruses evolve to encode orthologs of Bcl-2, including orf16 of KSHV, HVS and RRV, BHRF1 and BALF-1 of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and M11 of MHV68 (for review see [179]). KSHV Bcl-2 shows the modest identity (15–20%) to cBcl-2, but the solution structure of KSHV Bcl-2 is overall similar to that of cBcl-2, Bcl-xL, and MHV68 vBcl-2 in that they all share the central hydrophobic cleft [also called Bcl-2 homolog-3 (BH3)-peptide binding groove] [180–182]. Interestingly, this hydrophobic pocket serves not only for specific interaction with BH3-only molecule, but also for selective binding to Beclin1, as seen in both viral and cellular Bcl-2s [183,184]. Like its EBV counterpart BHRF1, KSHV Bcl-2 is expressed in early lytic phase and inhibits apoptosis in vitro induced by several stimuli, including Bax, viral cyclin, and sindbis virus infection as tested [26,185].

In spite of structural and functional similarity, vBcl-2s differ in important ways from their cellular counterpart. They display different binding affinity to BH3 peptides: the order of binding affinity of KSHV and MHV68 vBcl-2 is BAK > BAX > BAD, whereas that of cellular Bcl-2 is BAD > BAX > BAK [180,183], suggesting a somewhat different regulatory mechanism. In addition, the N-terminal long inhibitory loop between α1 and α2 is diminished in the most case of vBcl-2s, resulting in the viral evasion of host caspase cleavage and regulatory phosphorylation, all of which would otherwise inhibit cellular Bcl-2 antiapoptotic function [180,183]. Thus, vBcl-2s have evolved to have advantageous anti-apoptotic activities compared to their host counterpart. In regard to autophagy regulation, vBcl-2s exhibit higher binding affinity to Beclin1 and thus more robust and persistent inhibition of Beclin1-mediated autophagy even upon environmental stress, as compared to their cellular counterpart [186]. Ku et al. recently reveals that the MHV68 vBcl-2 has much tighter in vitro binding affinity towards Beclin1 peptide than towards BAK peptide [183]. The propensity of γ2-herpesvirus vBcl-2 to efficiently suppress autophagy implies that autophagy might in part account for the biological effects on viral persistent infection. On the other hand, it can be postulated that vBcl-2, by coordinately blocking both apoptosis and autophagy, might circumvent host immune response to establish and/or maintain persistent infection; the detail of which, however, remains to be understood completely.

3.4.2. vIAP (K7)

The caspase activity in the course of apoptosis can be directly inhibited by a conserved family of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAP). KSHV K7, a mitochondrial protein expressed in lytic replication, is originally identified as a viral ortholog of the human survivin (surviving-ΔEx2), a cellular IAP [187]. K7 has been shown to be able to protect cells from apoptosis induced by various stimuli in vitro [187,188], and this activity is partially attributed to its inhibition of caspase-3 activity by forming a bridge between cBcl-2 and the effector caspase-3. In addition, K7 is found to target cellular calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligan (CAML) to modulate intracellular calcium effluxes, thereof suppresses ER-stress induced apoptosis [188]. Further characterization by Feng et al. [189] extends the role of K7 beyond apoptosis modulation: it binds to and inhibits a regulator of the host ubiquitin/proteasome-pathway, thereof interferes with the right turnover of crucial host defense molecules such as p53 and IκB, which may facilitate the avoidance of host immune surveillance.

3.5. Evasion of cytotoxic T cell (CTL) and natural killer (NK) cell responses

3.5.1. K3 and K5-mediated downregulation of MHC class I molecule

CTL evasion is a prerequisite for persistent viral replication: this is particularly true of herpesviruses. Virtually, every herpesvirus implements at least one gene product to engage the MHC class I-restricted CTL responses by interfering with MHC protein synthesis, assembly, peptide-loading or cell surface transport (for review see [190,191]). KSHV encodes two gene products, K3 and K5 (also termed MIR1 and MIR2, respectively), which act in concert to efficiently downregulate the expression of MHC class I molecule on the surface of infected cells, thus prevent antiviral CTL responses [192–194]. K3 and K5 are highly homologous (~40% identity) and their expression is part of viral lytic replication cycle [195]. Both contain a specific zinc-binding motif, termed a RING-CH (really interesting new gene) domain with a non-classical C4HC3 conformation, at the N-terminus and two transmembrane domains in the central region, but vary in the C-terminal tail [195]. Notably, KSHV K3 and K5 are now recognized as the prototypes of a novel MARCH (membrane-associated RING-CH-containing) family of E3 ligases [196–199]. Although predominantly located in the ER, K3 and K5 do not affect the assembly or transport of MHC class I molecules through the secretory pathway. Instead, they mediate ubiquitination of cell surface MHC class I molecules; once ubiquitinated, MHC class I molecules are rapidly internalized and degraded by the lysosome [196,197]. Of special interest, K3 extensively down-regulates the expression of all MHC class I molecules in humans (HLA-A, -B, -C, and -E), whereas K5 exclusively downregulates HLA-A and HLA-B [192,194].

The structural requirements of MHC I down-regulation induced by K3 have been analyzed in detail. The intact RING-CH of E3 ubiquitin ligase activity is necessary for the ubiquitination of MHC class I molecule. Mutational ablation of the lysine residues in the MHC class I cytosolic tail abolishes both ubiquitin tagging and MHC class I downregulation [196,197,200]. However, the E3 ligase activity of K3, but not K5, can be lysine-independent, in that K3 can alternatively ubiquitinates the cysteine residues of target molecules [201]. The substrate specificity of K3 and K5, however, is determined by their transmembrane domains [196,202]. Upon association with its target protein, the RING-CH domain of K3 recruits E2 ubiquitin-conjugating (Ubc) enzymes and promotes transfer of the ubiquitin from the E2 onto the target protein. Two E2 UbcH5b/c and Ubc13 enzymes, recently identified by Duncan et al. [203], contribute to the Lys-63-polyubiquitination of class I molecules, which is a prerequisite for the efficient endocytosis and endolysosomal degradation of class I molecules. The C-terminal cytoplasmic tails of K3 and K5 carry a number of motifs including a tyrosine-based endocytosis motif, a stretch of four residues (NTRV) conserved between K3 and K5, a proline-rich potential SH3 binding domain (SH3B), and two acidic clusters (DE1 and DE2). Detailed mutational analyses indicate that the N-terminal RING-CH motif, the C-terminal tyrosine-based endocytosis motif, and the conserved NRTV residues of K3 contribute to the endocytosis of MHC class I molecules, whereas the C-terminal DE region is engaged in the lysosomal recruitment of MHC class I molecules [198]. These results demonstrate that K3 exerts controls at both the initial internalization step and the downstream lysosomal degradation step, notably, the actions of which are functionally and genetically separable.

The in vivo importance of K3/K5-mediated CTL evasion via MHC-I downregulation can be inferred from the K3 of MHV68, which is an ortholog of KSHV-K3. Stevenson et al. have shown that cells expressing MHV68 K3 are attenuated in their ability to present peptides to T cell hybridomas in a MHC-I restricted manner, indicating both potential evasion of CTL lysis and activation [204]. MHV68-K3 directly associates with and ubiquitinates the MHC-I molecules; however, in striking contrast to KSHV K3, MHV68 K3 targets them for proteasomal degradation. The K3 depletion of MHV68 has minimal effect on the viral clearance from the lung, but leads to attenuated viral latency amplification, a defect that can be reversed by CTL depletion [205]. Whether K3 and K5 have similar potent effect in KSHV infection is as yet unknown. Nonetheless, downregulation of class I molecules and co-stimulators is also observed in latent KSHV infected cells [206] suggesting that CTL evasion is a constitutive demand for KSHV.

3.5.2. K5-mediated downregulation of NK cell-activating molecules

NK cells confer rapid recognition and elimination of virally infected cells by direct lysis of infected targets through the release of cytotoxic granules (containing perforins and granzymes), and by secreting cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNFα to enhance the adaptive cellular responses against the cell. The activity of NK cell is fine-tuned with the integrated signalings from both activatory and inhibitory receptors through their engagements with positive or negative molecules on target cell surface. The most prominent negative molecule is MHC class I, which is present on virtually all healthy cells to prevent ‘self-attack’ by NK cells. Downregulation of MHC class I molecules from cell surface through any of a variety of mechanisms renders the cells sensitive to recognition and killing by NK cells, provided that an activating receptor is engaged. The activating NK receptors include the natural cytotoxicity receptor family (NKp30, NKp44, NKp46, NKp80), the C-type lectin-domain containing receptor NKG2D, the CD2 superfamily receptor 2b4 (CD244), and the IgG receptor CD16 [207]. The engagements of NKG2D with MHC class I-related chains (MIC) A and B have been implicated to play a central role in innate immunity, and be targeted by multiple viruses such as CMV and HIV [208–210]. Integrins, however, represent a distinct category of NK cell activating molecules. The engagement of integrin by intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) or ICAM-2 is sufficient to induce adhesion and stabilizes the interaction between NK cell and the infected target, a prerequisite for NK cell effector functions [211]. Engagements of these activating receptors by appropriate ligands initiate NK response for both cytolysis and cytokine production (for review see [212]).

As indicated, KSHV down-regulates surface MHC class I molecules via the K3 and K5-mediated ubiquitylation and lysosomal degradation. One would expect that this reduction of MHC class I expression may render KSHV-infected cells susceptible to NK cell killing. However, K5-expressing or K3/K5-coexpressing cells are more resistant to NK cell-mediated cytolysis than naïve cells. Further mechanistic studies reveal that, in addition to lowering the level of MHC class I, KSHV K5 (but not K3) significantly down-regulates ICAM-1 (CD54) and B7–2 (CD86) from the B cell surface, two co-activating molecules for NK cell, by inducing their endocytosis and degradation [193,194]. By down regulating ICAM from the cell surface, K5 reduces the ability of NK cells to maintain contact with the target cell and diminishes the likelihood of a positive signal being transmitted to NK cells. Notably, diminishing cell surface ICAM-1 and B7–2 not only evades NK cell recognition but also inhibits T cell stimulation [196]. The role of K5 in NK cell evasion is further extended recently by Thomas et al. [213], showing K5 also down-regulates MHC class I-related chain A (MICA) and activation-induced C-type lectin (AICL), two ligands for NK cells activatory receptors NKG2D and NKp80, respectively. Hence, K5 abrogates NK cell-mediated lysis, not by transmitting a negative signal, rather by preventing a positive one. Besides eluding NK cell recognition and cytolysis, K3 and K5 can inhibit the action of NK-activating cytokines IFNγ by downregulating the IFN-γ receptor. The effect of many other cytokines released by NK cells such as TNFα, chemokines can also be blocked by KSHV-encoded immuno-modulators as described in the previous sections. Due to our inability to test mutants of KSHV for pathogenicity in vivo, the importance of these interference with NK responses is still unclear.

Although K3 and K5 are designated as the lytic cycle viral genes, it has been found KSHV latently infected PEL cells also exhibit decreased MHC-I expression and impaired NK cell activity [214,215]. This may be explained by the abortive lytic expression of K3 or K5, or KSHV may use other ways to ensure comprehensive protection from host immune effectors at different phases of viral infection. In fact, recent study by Adang et al. [216] revealed that de novo KSHV infection of naive cells activates the K5 promoter and downregulates MHC class I and ICAM, which can be reversed by K5-specific siRNA-mediated silencing, suggesting the expression of early lytic protein K5 may be involved, at least in part, in downregulation of cell surface immunomodulatory molecules prior to the establishment of latency.

Taken together, K3 protein of KSHV is more pronounced in MHC-I molecule downregulation for CTL evasion than K5 protein, while K5 promiscuously down-regulates cell surface molecules including ICAM-1, B7–2, MICA/B, ALCL, CD1d, PECAM, ALCAM, and IFN-γR1 [193,217–220]. Orchestration of K3 and K5, as a result, suppresses both cytokine-mediated and cell-mediated immunity, which ensures a comprehensive avoidance of host immune controls.

4. Concluding remarks

The sophisticated evasion of the host immune control by KSHV provides a foundation for persistent viral infection and pathogenesis. In this review, we have outlined the various immune escape strategies employed by KSHV as schematized in Fig. 1 and summarized in Table 1. By probing the molecular details of each virus-designed or pirated immuno-modulators, researchers have gained important insights into not only the diverse aspects of virus–host interactions but also the inner workings of host immunity. Nonetheless, due to the absence of in vivo models for KSHV, it remains difficult to extrapolate in vitro observations to in vivo viral infection. Ongoing efforts to use closely related animal model systems such as RRV, HVS, and MHV68 along with developing tractable cell-culture systems of KSHV infection are certain to reveal hitherto unrecognized relationships between virus and host, and aid the development of immunotherapy for KSHV-associated disorders.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of KSHV immune evasion strategies.

Table 1.

KSHV modulation of the host immune system.

| Responses | ORF | Gene product | Celluar homolog | Functions | Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complement cascade | ORF4 | KCP | RCA | Blocks complement activation | Enhances C3 convertase decay; prevents C3b deposition; factor I cofactor activity |

| IFN signaling | K9 | vIRF1 | IRF | Inhibits IRF3-mediated transcription; cell transformation | P300/CBP sequestration; antagonizes p53, ATM, GRIM 19 activity and TGFβ signaling? |

| K11.1-K11 | vIRF2 | IRF | Inhibits IRF3-mediated transcription | ||

| K10.5-K10.6 | vIRF3 | IRF | Inhibits IRF7-mediated transcription | Inhibition of IRF7 DNA binding | |

| ORF50 | RTA | Inhibits IRF7 activation | IRF7 ubiquitination and degradation | ||

| ORF45 | Inhibits IRF7 activation | Inhibition of IRF7 phosphorylation/nucleartranslocation | |||

| K8 | K-bZIP | Inhibits IRF3-mediated transcription | Transcription repressor of IFN-β promoter | ||

| Chemokine Network | K4 | vCCL2 | CC chemokine | Th2 chemotaxis, angiogenesis | CCR3 agonist; C-, CC-, CXC-, CX3C-R antagonist |

| K6 | vCCL1 | CC chemokine | Th2 chemotaxis, angiogenesis | CCR8 agonist | |

| K4.1 | vCCL3 | CC chemokine | Th2 chemotaxis, angiogenesis | CCR4 agonist | |

| ORF74 | vGPCR | GPCR | Inflammation, angiogenesis; cell transformation | Activates PI3K/AKT/mT0R pathway; activates NFkB, AP-1, HIF-1α trascriptional activities | |

| K2 | vIL6 | IL6 | Inflammation, angiogenesis | IFNa-inducible; gp80-independent signaling; activates JAK/STAT and MAPK pathway | |

| K12 | Kaposin B | Increases cytokines release | Activates MK2, blocks cytokine mRNA decay | ||

| K14 | vCD200 | CD200 | Suppress macrophage activity | CD200R-mediated inhibitory signaling | |

| Apoptosis and autophagy | K13 | vFLIP | FLIP | Anti-apoptosis, in cell transformation spindle shape, inflammation | Blocks activation of caspase 8? NFκB pathway activation |

| ORF16 | vBcl-2 | Bcl-2 | Anti-apoptosis, anti-autophagy | Inhibits pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins; inhibits Beclin1-mediated autophagy | |

| K7 | vIAP | IAP | Anti-apoptosis, interferes with ubiquitin-proteasome pathway | Inhibits caspase 3 and CAML activity; inhibits PLIC-regulated Ub-proteasome pathway | |

| ORF73 | LANA | Cell growth transformation | Inhibits p53, Rb, GSK-3β; and TGF-β pathways | ||

| ORF50 | RTA | Anti-apoptosis | Inhibits p53 transcriptional activity | ||

| CTL and NK responses | K3 | vMIR1 | MARCH | CTL cell evasion | Downregulation of HLA-A, -B, -C, and -E |

| K5 | VMIR2 | MARCH | CTL and NK cell evasion | Downregulation of HLA-A, -B, ICAM-1, B7–2, MICA/B, ALCL, CDld, PECAM, ALCAM and IFNγRI |

Acknowledgements

We thank Steven Lee for the critical reading of the manuscript. Dr. Chengyu Liang is a fellow of the leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

References

- [1].Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, Lee F, Culpepper J, Knowles DM, et al. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. Science 1994;266:1865–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ganem D KSHV infection and the pathogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Annu Rev Pathol 2006;1:273–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schulz TF. Epidemiology of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8. Adv Cancer Res 1999;76:121–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sarid R, Olsen SJ, Moore PS. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: epidemiology, virology, and molecular biology. Adv Virus Res 1999;52:139–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, Cacoub P, Cazals-Hatem D, Babinet P, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s disease. Blood 1995;86:1276–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Alexander L, Denekamp L, Knapp A, Auerbach MR, Damania B, Desrosiers RC. The primary sequence of rhesus monkey rhadinovirus isolate 26–95: sequence similarities to Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and rhesus monkey rhadinovirus isolate 17577. J Virol 2000;74:3388–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Neipel F, Albrecht JC, Fleckenstein B. Cell-homologous genes in the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated rhadinovirus human herpesvirus 8: determinants of its pathogenicity? J Virol 1997;71:4187–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Russo JJ, Bohenzky RA, Chien MC, Chen J, Yan M, Maddalena D, et al. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996;93:14862–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Searles RP, Bergquam EP, Axthelm MK, Wong SW. Sequence and genomic analysis of a Rhesus macaque rhadinovirus with similarity to Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8. J Virol 1999;73:3040–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jung JU, Choi JK, Ensser A, Biesinger B. Herpesvirus saimiri as a model for gammaherpesvirus oncogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol 1999;9:231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Verma SC, Lan K, Robertson E. Structure and function of latency-associated nuclear antigen. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2007;312:101–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ballestas ME, Chatis PA, Kaye KM. Efficient persistence of extrachromosomal KSHV DNA mediated by latency-associated nuclear antigen. Science 1999;284:641–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lan K, Kuppers DA, Verma SC, Robertson ES. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded latency-associated nuclear antigen inhibits lytic replication by targeting Rta: a potential mechanism for virus-mediated control of latency. J Virol 2004;78:6585–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ossevoort M, Visser BM, van den Wollenberg DJ, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Melief CJ, et al. Creation of immune ‘stealth’ genes for gene therapy through fusion with the Gly-Ala repeat of EBNA-1. Gene Ther 2003;10:2020–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bennett NJ, May JS, Stevenson PG. Gamma-herpesvirus latency requires T cell evasion during episome maintenance. PLoS Biol 2005;3:e120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zaldumbide A, Ossevoort M, Wiertz EJ, Hoeben RC. In cis inhibition of antigen processing by the latency-associated nuclear antigen I of Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus. Mol Immunol 2007;44:1352–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Friborg J Jr, Kong W, Hottiger MO, Nabel GJ. p53 inhibition by the LANA protein of KSHV protects against cell death. Nature 1999;402:889–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Radkov SA, Kellam P, Boshoff C. The latent nuclear antigen of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus targets the retinoblastoma-E2F pathway and with the oncogene Hras transforms primary rat cells. Nat Med 2000;6:1121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fujimuro M, Wu FY, ApRhys C, Kajumbula H, Young DB, Hayward GS, et al. A novel viral mechanism for dysregulation of beta-catenin in Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency. Nat Med 2003;9:300–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Di Bartolo DL, Cannon M, Liu YF, Renne R, Chadburn A, Boshoff C, et al. KSHV LANA inhibits TGF-{beta} signaling through epigenetic silencing of the TGF-{ beta} type II receptor. Blood 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chang Y, Moore PS, Talbot SJ, Boshoff CH, Zarkowska T, Godden K, et al. Cyclin encoded by KS herpesvirus. Nature 1996;382:410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Direkze S, Laman H. Regulation of growth signalling and cell cycle by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genes. Int J Exp Pathol 2004;85:305–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Swanton C, Mann DJ, Fleckenstein B, Neipel F, Peters G, Jones N. Herpes viral cyclin/Cdk6 complexes evade inhibition by CDK inhibitor proteins. Nature 1997;390:184–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Koopal S, Furuhjelm JH, Jarviluoma A, Jaamaa S, Pyakurel P, Pussinen C, et al. Viral oncogene-induced DNA damage response is activated in Kaposi sarcoma tumorigenesis. PLoS Pathog 2007;3:1348–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ojala PM, Tiainen M, Salven P, Veikkola T, Castanos-Velez E, Sarid R, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded v-cyclin triggers apoptosis in cells with high levels of cyclin-dependent kinase 6. Cancer Res 1999;59:4984–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Verschuren EW, Klefstrom J, Evan GI, Jones N. The oncogenic potential of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus cyclin is exposed by p53 loss in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Cell 2002;2:229–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sarek G, Kurki S, Enback J, Iotzova G, Haas J, Laakkonen P, et al. Reactivation of the p53 pathway as a treatment modality for KSHV-induced lymphomas. J Clin Invest 2007;117:1019–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Djerbi M, Screpanti V, Catrina AI, Bogen B, Biberfeld P, Grandien A. The inhibitor of death receptor signaling, FLICE-inhibitory protein defines a new class of tumor progression factors. J Exp Med 1999;190:1025–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Chugh P, Matta H, Schamus S, Zachariah S, Kumar A, Richardson JA, et al. Constitutive NF-kappaB activation, normal Fas-induced apoptosis, and increased incidence of lymphoma in human herpes virus 8 K13 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:12885–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chaudhary PM, Jasmin A, Eby MT, Hood L. Modulation of the NF-kappa B pathway by virally encoded death effector domains-containing proteins. Oncogene 1999;18:5738–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Guasparri I, Keller SA, Cesarman E. KSHV vFLIP is essential for the survival of infected lymphoma cells. J Exp Med 2004;199:993–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [33].Sun Q, Zachariah S, Chaudhary PM. The human herpes virus 8-encoded viral FLICE-inhibitory protein induces cellular transformation via NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem 2003;278:52437–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Matta H, Chaudhary PM. Activation of alternative NF-kappa B pathway by human herpes virus 8-encoded Fas-associated death domain-like IL-1 beta-converting enzyme inhibitory protein (vFLIP). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:9399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sun Q, Matta H, Chaudhary PM. The human herpes virus 8-encoded viral FLICE inhibitory protein protects against growth factor withdrawal-induced apoptosis via NF-kappa B activation. Blood 2003;101:1956–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sun Q, Matta H, Chaudhary PM. Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpes virus-encoded viral FLICE inhibitory protein activates transcription from HIV-1 Long Terminal Repeat via the classical NF-kappaB pathway and functionally cooperates with Tat. Retrovirology 2005;2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Keller SA, Schattner EJ, Cesarman E. Inhibition of NF-kappaB induces apoptosis of KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cells. Blood 2000;96: 2537–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Grossmann C, Podgrabinska S, Skobe M, Ganem D. Activation of NF-kappaB by the latent vFLIP gene of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for the spindle shape of virus-infected endothelial cells and contributes to their proinflammatory phenotype. J Virol 2006;80:7179–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sun Q, Matta H, Lu G, Chaudhary PM. Induction of IL-8 expression by human herpesvirus 8 encoded vFLIP K13 via NF-kappaB activation. Oncogene 2006;25:2717–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ye FC, Zhou FC, Xie JP, Kang T, Greene W, Kuhne K, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent gene vFLIP inhibits viral lytic replication through NF-{kappa}B-mediated suppression of the AP-1 pathway. A novel mechanism of virus control of latency. J Virol 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Grossmann C, Ganem D. Effects of NFkappaB activation on KSHV latency and lytic reactivation are complex and context-dependent. Virology 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sadler R, Wu L, Forghani B, Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B, et al. A complex translational program generates multiple novel proteins from the latently expressed kaposin (K12) locus of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 1999;73:5722–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].McCormick C, Ganem D. The kaposin B protein of KSHV activates the p38/MK2 pathway and stabilizes cytokine mRNAs. Science 2005;307:739–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].McCormick C, Ganem D. Phosphorylation and function of the kaposin B direct repeats of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 2006;80:6165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Cullen BR. Viruses and microRNAs. Nat Genet 2006;38(Suppl.): S25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Grey F, Nelson J. Identification and function of human cytomegalovirus microRNAs. J Clin Virol 2008;41:186–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gottwein E, Cai X, Cullen BR. Expression and function of microRNAs encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2006;71:357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Samols MA, Skalsky RL, Maldonado AM, Riva A, Lopez MC, Baker HV, et al. Identification of cellular genes targeted by KSHV-encoded microRNAs. PLoS Pathog 2007;3:e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schafer A, Cai X, Bilello JP, Desrosiers RC, Cullen BR. Cloning and analysis of microRNAs encoded by the primate gamma-herpesvirus rhesus monkey rhadinovirus. Virology 2007;364:21–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Gottwein E, Mukherjee N, Sachse C, Frenzel C, Majoros WH, Chi JT, et al. A viral microRNA functions as an orthologue of cellular miR-155. Nature 2007;450:1096–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].McClure LV, Sullivan CS. Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus taps into a host microRNA regulatory network. Cell Host Microbe 2008;3:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Skalsky RL, Samols MA, Plaisance KB, Boss IW, Riva A, Lopez MC, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. J Virol 2007;81:12836–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Gao SJ, Deng JH, Zhou FC. Productive lytic replication of a recombinant Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in efficient primary infection of primary human endothelial cells. J Virol 2003;77:9738–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tang J, Gordon GM, Muller MG, Dahiya M, Foreman KE. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency-associated nuclear antigen induces expression of the helix-loop-helix protein Id-1 in human endothelial cells. J Virol 2003;77:5975–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Boulanger MJ, Chow DC, Brevnova E, Martick M, Sandford G, Nicholas J, et al. Molecular mechanisms for viral mimicry of a human cytokine: activation of gp130 by HHV-8 interleukin-6. J Mol Biol 2004;335:641–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chatterjee M, Osborne J, Bestetti G, Chang Y, Moore PS. Viral IL-6-induced cell proliferation and immune evasion of interferon activity. Science 2002;298:1432–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Goodbourn S, Didcock L, Randall RE. Interferons: cell signalling, immune modulation, antiviral response and virus countermeasures. J Gen Virol 2000;81:2341–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Honda K, Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. Type I interferon [corrected] gene induction by the interferon regulatory factor family of transcription factors. Immunity 2006;25:349–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Honda K, Taniguchi T. IRFs: master regulators of signalling by Toll-like receptors and cytosolic pattern-recognition receptors. Nat Rev Immunol 2006;6:644–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Pestka S, Krause CD, Walter MR. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol Rev 2004;202:8–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Honda K, Yanai H, Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. Regulation of the type I IFN induction: a current view. Int Immunol 2005;17:1367–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Weaver BK, Kumar KP, Reich NC. Interferon regulatory factor 3 and CREB-binding protein/p300 are subunits of double-stranded RNA-activated transcription factor DRAF1. Mol Cell Biol 1998;18:1359–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Stetson DB, Medzhitov R. Type I interferons in host defense. Immunity 2006;25:373–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].van Boxel-Dezaire AH, Rani MR, Stark GR. Complex modulation of cell type-specific signaling in response to type I interferons. Immunity 2006;25:361–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem 1998;67:227–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Katze MG, He Y, Gale M Jr. Viruses and interferon: a fight for supremacy. Nat Rev Immunol 2002;2:675–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Cebulla CM, Miller DM, Sedmak DD. Viral inhibition of interferon signal transduction. Intervirology 1999;42:325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Garcia-Sastre A Mechanisms of inhibition of the host interferon alpha/beta-mediated antiviral responses by viruses. Microbes Infect 2002;4:647–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Dittmer DP. Transcription profile of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in primary Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions as determined by real-time PCR arrays. Cancer Res 2003;63:2010–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Rivas C, Thlick AE, Parravicini C, Moore PS, Chang Y. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA2 is a B-cell-specific latent viral protein that inhibits p53. J Virol 2001;75:429–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Parravicini C, Chandran B, Corbellino M, Berti E, Paulli M, Moore PS, et al. Differential viral protein expression in Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-infected diseases: Kaposi’s sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman’s disease. Am J Pathol 2000;156:743–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Cunningham C, Barnard S, Blackbourn DJ, Davison AJ. Transcription mapping of human herpesvirus 8 genes encoding viral interferon regulatory factors. J Gen Virol 2003;84:1471–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D, Taniguchi T. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Gao Y, Smith PR, Karran L, Lu QL, Griffin BE. Induction of an exceptionally high-level, nontranslated, Epstein-Barr virus-encoded polyadenylated transcript in the Burkitt’s lymphoma line Daudi. J Virol 1997;71:84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Zimring JC, Goodbourn S, Offermann MK. Human herpesvirus 8 encodes an interferon regulatory factor (IRF) homolog that represses IRF-1-mediated transcription. J Virol 1998;72:701–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Burysek L, Yeow WS, Lubyova B, Kellum M, Schafer SL, Huang YQ, et al. Functional analysis of human herpesvirus 8-encoded viral interferon regulatory factor 1 and its association with cellular interferon regulatory factors and p300. J Virol 1999;73:7334–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Li M, Lee H, Guo J, Neipel F, Fleckenstein B, Ozato K, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral interferon regulatory factor. J Virol 1998;72:5433–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Lin R, Genin P, Mamane Y, Sgarbanti M, Battistini A, Harrington WJ Jr, et al. HHV-8 encoded vIRF-1 represses the interferon antiviral response by blocking IRF-3 recruitment of the CBP/p300 coactivators. Oncogene 2001;20:800–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Pozharskaya VP, Weakland LL, Zimring JC, Krug LT, Unger ER, Neisch A, et al. Short duration of elevated vIRF-1 expression during lytic replication of human herpesvirus 8 limits its ability to block antiviral responses induced by alpha interferon in BCBL-1 cells. J Virol 2004;78:6621–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Fuld S, Cunningham C, Klucher K, Davison AJ, Blackbourn DJ. Inhibition of interferon signaling by the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus full-length viral interferon regulatory factor 2 protein. J Virol 2006;80:3092–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Joo CH, Shin YC, Gack M, Wu L, Levy D, Jung JU. Inhibition of interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7)-mediated interferon signal transduction by the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral IRF homolog vIRF3. J Virol 2007;81:8282–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]