Despite remarkable progress in understanding the immune response to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), optimal management of immune function during severe viral infections remains a major issue among critically ill patients. In this issue of Anesthesia & Analgesia, a clinical study by Spinetti et al1 revealed serious concerns about the development of immunosuppression among coronavirusdisease2019 (COVID-19) patients requiring hospitalization in an intensive care unit (ICU). A significant number of patients appeared to develop immune dysfunction, as evidenced by reduced amounts of monocytic human leukocyte antigen-DR (mHLA-DR). A similar observation has been reported in patients who survive severe sepsis or trauma, but later develop life-threatening immunosuppression.2–4

HLA-DR is a class IIhuman leukocyte antigen (HLA) expressed on the cell surface of antigen-presenting cells, including monocytes, differentiated macrophages and dendritic cells, as well as B cells. Since the first description of role of HLA-DR in immunosuppression,5 HLA-DR expression on monocytes has been subsequently proven to be a reliable marker for evaluating immune dysfunction and risk of secondary bacterial infections in sepsis and trauma patients.3,6–8 Thus, reduced amounts of HLA-DR can also place COVID-19 patients at high risk of secondary and severe bacterial nosocomial infections. This observation is consistent with a clinical report of secondary bacterial infections and end-organ injury among COVID-19 patients requiring ICU care.9

A recent examination of HLA variations among the world population revealed a significant impact of HLAs on the cellular immune response, in particular, on peptides from coronavirus-infected patients. HLA-B*15:03 exhibited the greatest capacity to present highly conserved, shared SARS-CoV2 peptides to immune cells.10 Subsequent studies have recently confirmed that immune dysregulation in COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure is associated with a significant downregulation of monocyte HLA-DR.11

An excessive inflammatory response to SARS-CoV2 has been thought to be the major cause of disease severity and death among patients with COVID-19 in the ICU setting.12 In this context, exaggerated neutrophil and macrophage/monocyte proinflammatory activation may trigger development of immune dysfunction, including immune tolerance (defective response to bacterial products, eg, lipopolysaccharide) and reduced host immune capacity against bacterial infections.13–15 Such inflammatory mechanisms can be relevant in the development of immunosuppression in sepsis survivors, consistent with reduced HLA-DR expression on monocytes after an initial activation of immune cells during sepsis syndrome.

However, recent studies have indicated that patients with SARS-CoV2 infection admitted to an ICU have significantly lower levels of cytokine production, as compared to sepsis-related ARDS.16 Therefore, such findings dispute a relevance of “cytokine storm” in COVID-19–related development of severe respiratory dysfunction and failure. These findings also indicate that more research is needed to better define the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV2and associated immunosuppression.

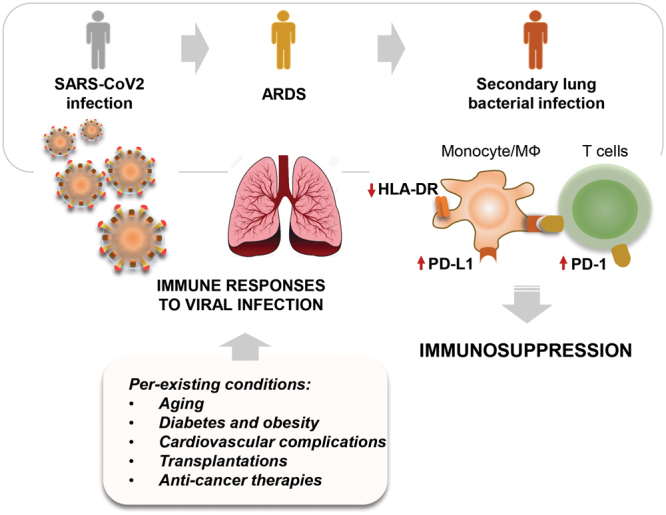

Notably, the mechanisms underlying the downregulation of HLA-DR in sepsis and trauma are also not well understood. Nevertheless, once HLA-DR is decreased or deficient, this event upregulates surface expression of the negative co-stimulatory molecules programmed death 1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA), and their corresponding ligands, such as PD-1 ligand (PD-L1). These actions can compromise innate and adaptive immune systems, including cluster of differentiation (CD)8- and anergic CD4-positive T cells, and inducing T cell apoptosis. It could be speculated if these are relevant immunosuppressive mechanisms associated with severe SARS-CoV2 infections (Figure). Furthermore, although HLA-DR is diminished in monocytes during sepsis and viral infection, many other events can trigger immunosuppression, including T cell senescence, exhaustion, and skewing toward the TH17 phenotype.17

Figure.

Reduced levels of HLA-DR are associated with the development of immunosuppression, high risk of secondary bacterial infections, and end-organ failure in intensive care unit patients with SARS-CoV2. ARDS indicates xxx; HLA-DR, human leukocyte antigen-DR; MФ, macrophages; PD-L1, programmed death 1 ligand; SARS-CoV2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The development of immunosuppression is certainly linked to host’s maladaptive response to SARS-CoV2, likely related to preexisting conditions like aging, diabetes, and cardiovascular complications.18 Immunosuppression elicited in anticancer treatments and graft transplantations are also significant issues leading to infections, including worse outcomes with SARS-CoV2 infection.

Several epidemiological studies have shown that aging is disproportionally linked to more cases, increased severity of organ injury, and mortality related to COVID-19.19,20 This is a significant issue because aging is characterized by a collective loss of immune responsiveness and paradoxically low-grade chronic inflammation (“inflammaging”).21 Importantly, although CD14+CD16+ monocytes significantly increased with age, but they also displayed reduced HLA-DR surface expression in the elderly.22 It is important to note that a reduced abundance of HLA-DR is likely not a sole biological event becausemany hallmarks of aging are coupled with host–coronavirus interactions in direct and indirect ways, including genomic instability, reduced mitochondrial function, epigenetic alterations, telomere attrition, and impaired autophagy.19 In particular, mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic profile of immune and alveolar epithelial cells play a crucial role in bioenergetic maladaptation in response to viral infections.23 Mitochondrial antiviralsignaling (MAVS) proteins can be released/activated upon viral infection, including SARS-CoV2. MAVS-mediated apoptosis can be suppressed by viral proteins and prevent mitochondrial death or apoptosis to limit virus propagation.24 On the other hand, leukopenia developed in approximately 70% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, and the mechanism of this cell line death/exhaustion remains to be determined.25

Diabetes and obesity are leading causes of the morbidity and mortality associated with viral infection–related cardiovascular complications. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a serious preexisting metabolic syndrome with adverse outcomes in patients with hemagglutinin type 1 and neuraminidase type 1 (influenza strain) (H1N1) influenza and SARS-CoV2 in ICU.26–29 Diabetes-related hyperglycemia is closely linked to thedevelopment of acute ketoacidosis and other metabolic alteration, as well as chronic low-gradeinflammation.30 A possible impact of T2DM on mortality due to viral infections is the abundance of glucose that favors virus replication. Diabetes is also characterized by innate immunity dysfunction, including reduced chemotaxis, phagocytosis, andpathogen killing by monocytes and polymorphonuclear neutrophils.31 Interestingly, it has been suggested that HLA regulates immunoreactive inflammation or infection associated with type 2 diabetes. However, the role of HLA alleles in pathogenesis of T2DM and T1DM, and subsequent complications are less clear, as both positive and negative associations of DR alleles have been observed.32,33 Such discrepancies are likely because diabetes mellitus is a multifactorial disease. Nevertheless, it would be interesting to determine if a decrease of specific HLA-DR alleles contributes to worst outcome in patients withdiabetesand critically illobese patients with COVID-19.

While interventions available for sepsis and severe trauma are limited to fluid resuscitation and antibiotics, immunomodulatory mechanisms remain the major targets for thedevelopment of effective therapies. Perhaps, successful completion of a clinical trial for PD-L1 in sepsis could also be tested as a therapy for COVID-19–related immunosuppression. Given results obtained by Spinetti et al,1 this seems to be a relevant approach to diminishing morbidity and mortality among ICU patients with COVID-19. Another potential benefit is utilization of HLA-DR variants as a prognostic tool to identify individuals with a higher risk for severe infection and hospitalization due to COVID-19.

DISCLOSURES

Name: Jaroslaw W. Zmijewski, PhD.

Contribution: This author helped develop the concept, write the manuscript, and design Figure 1.

Name: Jean-Francois Pittet, MD.

Contribution: This author helped edit and revise the final version of the manuscript.

This manuscript was handled by: Thomas R. Vetter, MD, MPH.

FOOTNOTES

GLOSSARY

- ARDS

- xxx

- BTLA

- B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator

- CD

- cluster of differentiation

- COVID-19

- coronavirus disease 2019

- CTLA-4

- cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4

- H1N1

- hemagglutinin type 1 and neuraminidase type 1 (influenza strain)

- HLA

- human leukocyte antigen

- HLA-B*15:03

- xxx

- ICU

- intensive care unit

- MФ

- macrophages

- MAVS

- mitochondrial antiviral signaling

- mHLA-DR

- monocytic human leukocyte antigen-DR

- PD-1

- programmed death 1

- PD-L1

- programmed death 1 ligand

- SARS-CoV2

- severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- T1DM

- type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T2DM

- type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TH17

- xxx

Funding: This work was supported by grants from US Department of Defense (W81XWH-17-1-0577 [to J.W.Z]) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 HL139617-01 [to J.W.Z]).

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Reprints will not be available from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Spinetti T, Hirzel C, Fux M, et al. Reduced monocytic HLA-DR expression indicates immunosuppression in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Anesth Analg. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venet F, Tissot S, Debard AL, et al. Decreased monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression after severe burn injury: correlation with severity and secondary septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1910–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfortmueller CA, Meisel C, Fux M, Schefold JC. Assessment of immune organ dysfunction in critical illness: utility of innate immune response markers. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2017;5:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venet F, Rimmelé T, Monneret G. Management of sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Crit Care Clin. 2018;34:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volk HD, Thieme M, Heym S, et al. Alterations in function and phenotype of monocytes from patients with septic disease—predictive value and new therapeutic strategies. Behring Inst Mitt. 1991:208–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA. 2011;306:2594–2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venet F, Demaret J, Gossez M, Monneret G. Myeloid cells in sepsis-acquired immunodeficiency. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhuang Y, Peng H, Chen Y, Zhou S, Chen Y. Dynamic monitoring of monocyte HLA-DR expression for the diagnosis, prognosis, and prediction of sepsis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2017;22:1344–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen A, David JK, Maden SK, et al. Human leukocyte antigen susceptibility map for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. J Virol. 2020;94:e00510–e00520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Netea MG, Rovina N, et al. Complex immune dysregulation in COVID-19 patients with severe respiratory failure. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:992.e3–1000.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venet F, Monneret G. Advances in the understanding and treatment of sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:121–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delano MJ, Ward PA. Sepsis-induced immune dysfunction: can immune therapies reduce mortality? J Clin Invest. 2016;126:23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundar KM, Sires M. Sepsis induced immunosuppression: implications for secondary infections and complications. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17:162–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinha P, Matthay MA, Calfee CS. Is a “Cytokine Storm” relevant to COVID-19? JAMA Intern Med. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Biasi S, Meschiari M, Gibellini L, et al. Marked T cell activation, senescence, exhaustion and skewing towards TH17 in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salimi S, Hamlyn JM. COVID-19 and crosstalk with the hallmarks of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies NG, Klepac P, Liu Y, et al. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg EL, Shaw AC, Montgomery RR. How inflammation blunts innate immunity in aging. Interdiscip Top Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;43:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seidler S, Zimmermann HW, Bartneck M, Trautwein C, Tacke F. Age-dependent alterations of monocyte subsets and monocyte-related chemokine pathways in healthy adults. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020;583:459–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei Y, Moore CB, Liesman RM. MAVS-mediated apoptosis and its inhibition by viral proteins. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan L, Wang Q, Zhang D. Lymphopenia predicts disease severity of COVID-19: a descriptive and predictive study. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang JK, Feng Y, Yuan MY. Plasma glucose levels and diabetes are independent predictors for mortality and morbidity in patients with SARS. Diabet Med. 2006;23:623–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoen K, Horvat N, Guerreiro NFC, de Castro I, de Giassi KS. Spectrum of clinical and radiographic findings in patients with diagnosis of H1N1 and correlation with clinical severity. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussain A, Bhowmik B, do Vale Moreira NC. COVID-19 and diabetes: knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu X, Pan X, Zhou W, et al. Clinical epidemiological analyses of overweight/obesity and abnormal liver function contributing to prolonged hospitalization in patients infected with COVID-19. Int J Obes (Lond). 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knapp S. Diabetes and infection: is there a link?—a mini-review. Gerontology. 2013;59:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geerlings SE, Hoepelman AI. Immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;26:259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marzban A, Kiani J, Hajilooi M, Rezaei H, Kahramfar Z, Solgi G. HLA class II alleles and risk for peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes patients. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:1839–1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nomura S, Shouzu A, Omoto S, et al. Genetic analysis of HLA, NA and HPA typing in type 2 diabetes and ASO. Int J Immunogenet. 2006;33:117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]