Abstract

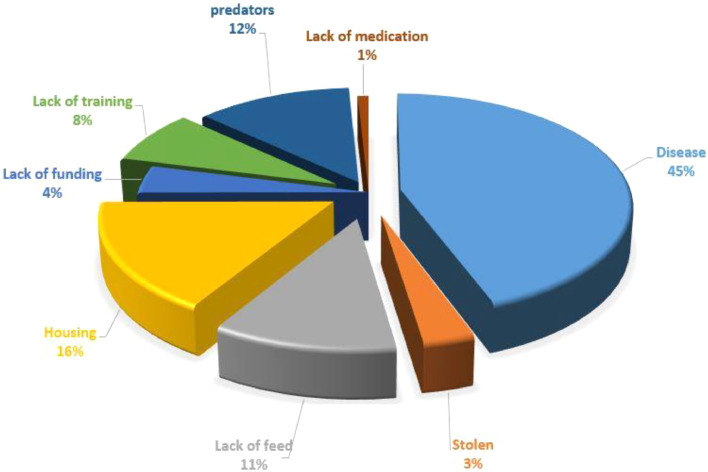

The breeding of local chicken is an important source of animal protein and income for the rural populations of Niger, and the improvement of its productivity requires a better knowledge of production practices. Hence, a socio-economic and technical survey was undertaken from July to August 2017 in order to provide necessary information on the practice of family poultry keeping in Niger. For this purpose, two hundred and sixteen (216) producers were interviewed in the different agro-ecological zones of Niger using structured questionnaire. Results from the study revealed that 43.1% of local chicken producers are women. The most production purpose of the chicken in Niger is for selling (38.31%), self-consumption (37.74%) and donation (22.99%). Scavenging is the most dominant feeding system (92.1%). Constraints related to family poultry production as identified by the study are mainly diseases (45%), lack of housing (16%) which favors predation, lack of food (11%) and lack of training (8%). It is clear that the development of the sector necessarily involves strengthening the surveillance of avian diseases, coupled with veterinary monitoring and supervision of producers.

Keyword: Local chicken, Diversity, Breeding, Characterization, Niger

1. Introduction

In Africa, family poultry production is practiced by more than 80% of the population, mostly concentrated in rural areas, and plays an important economic role for rural, urban and peri‑urban areas (Fotsa, 2008).

In Niger, poultry breeding is dominated by family poultry, which accounts for 96% of all local breeds combined, compared with 3% for modern breeds. In the total of indigenous poultry Chicken represent 55% (RGAC, 2008). This activity contributes to the food security of populations, particularly in rural areas where it is the main source of animal protein (Amadou Moussa, Idi, & Benabdeljelil, 2010), and contributes also to the reduction of poverty in the peri‑urban and rural areas by providing substantial income for producers (RGAC, 2008). However, the keeping of the local chicken of Niger meets several problems like the producers’ lack of knowledge about relevant conditions of production, health care. It is to overcome this lack of knowledge that this socio-economic and technical characterization study was initiated in order to provide necessary information on the practice of rural family poultry keeping production and to consider the prospects for improvement.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Area of study

The study covered 24 localities/villages across the four agro-ecological zones of Niger. These agro-ecological zones do not receive the same annual rainfall: Sahelo-Sudanian zones (600–800 mm/year), Sahelian (300–600 mm/year), Sahelo-Saharian (300-150 mm/year) and Saharan zone (less than 150 mm/year) (PANA, 2006). The distribution of localities by zone was made by considering the producing areas of the local chicken. Six localities were sampled in the Sahelo-Sudanese zone, 12 localities in the Sahelian zone, 4 localities in the Sahelo-Saharian zone and 2 localities in the Saharian zone (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution and number of areas sampled by agro-ecological zone.

2.2. Data collection process

The target group of this survey are both men and women producing local chicken. A total of 216 local chicken producers were sampled throughout the whole country with an average of 9 producers/locality. The selection of these producers was guided by the head of each village who knows best who is practicing and having more seniority in family poultry keeping.

An interview was carried out with each producer to inquire about his/her practice of local chicken production (whole questionnaire in Annex A). Most often, the interviews were done in the morning while taking care to inform the producers before through the village chief.

2.3. Ethical Statement

The National Committee of Ethics on Health Research authorized us to collect this data (authorization No.010/2017/CNERS).

All the producers who participated in this survey were first informed about the main purpose of the study and their participation was voluntary and anonymous. A verbal agreement was obtained from each producer at the beginning of his interview.

2.4. Data analysis

All the data collected were processed with Excel 2016 and subjected to a descriptive analysis with SPSS software (Statistical Package for Social Sciences.) Version 18.0.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-economic characteristics of producers

Local chicken breeding in Niger is practiced majority by men (56.9%). These producers are mostly married (86.1%) and 49.5% of them are between 30 and 50 years old. The practice of poultry farming in Niger is an old activity (67.6% of the respondents kept poultry for more than 5 years). Personal investment is the main source of funding for local chicken farming in Niger (82.4%). The majority of producers (81.5%) have never received training or capacity building on the practice of poultry farming. The main objective of the local chicken breeding in Niger is selling (38.31%), self-consumption (37.74%) and gift/donation (22.99%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socioeconomic Status of local chicken breeders.

| Parameters and variables | Sample size | Frequencies (%) | Parameters and variables | Sample size | Frequencies (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer gender | Secondary activity | ||||

| Women | 93 | 43.1 | Animal production | 155 | 71.67 |

| Men | 123 | 56.9 | Trade | 40 | 18.43 |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | Fishing | 3 | 1.37 |

| Age group | craft | 13 | 6.14 | ||

| <30 | 47 | 21.8 | Household | 3 | 1.36 |

| 30–50 | 107 | 49.5 | civil servant | 1 | 0.68 |

| 50–70 | 58 | 26.9 | Student | 1 | 0.34 |

| >70 | 4 | 1.9 | Total | 216 | 100.0 |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | |||

| Position in the family | Seniority in poultry farming | ||||

| Householder | 123 | 56.9 | <2 | 18 | 8.3 |

| spouse | 82 | 38.0 | 2-5 | 52 | 24.1 |

| child | 11 | 5.1 | >5 | 146 | 67.6 |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | Total | 216 | 100.0 |

| Marital status | Purpose of poultry farming | ||||

| Maried | 171 | 86.1 | Sell | 83 | 38.31 |

| Single | 28 | 6 | Self-consumption | 81 | 37.74 |

| Divorced | 5 | 2.3 | Gift/donation | 50 | 22.99 |

| Widower/widow | 12 | 5.6 | Distraction | 2 | 0.96 |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | Total | 216 | 100.0 |

| Source of funding | Training in poultry breeding | ||||

| Personal funding | 178 | 82.4 | Yes | 40 | 18.5 |

| Credit | 2 | 0.9 | No | 176 | 81.5 |

| Grant state | 2 | 0.9 | Total | 216 | 100.0 |

| Gift/donation | 18 | 8.3 | |||

| Project | 16 | 7.4 | |||

| Total | 216 | 100.0 |

3.2. Composition of the poultry flock

The poultry flocks consisted of several species. The average flock size of chicken represents the largest proportion. Out of a total of 2596 poultry encountered, 59.20% are chicken. This number of chicken is followed by the guinea fowl (18.70%), then the pigeons (15.51%) and finally the ducks, geese and turkeys with respectively 6.11%, 0.34% and 0.14% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Composition of poultry flocks and genetic types of hens raised in Niger.

| Parameter | Species of poultry | Sample size | Frequencies (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition of poultry flocks | Chicken | 2596 | 59.20 |

| Ducks | 268 | 6.11 | |

| Geese | 15 | 0.34 | |

| Turkeys | 6 | 0.14 | |

| 00Guinea fowl | 820 | 18.70 | |

| Pigeons | 680 | 15.51 | |

| Total | 4385 | 100.0 |

3.3. Technical characteristics

3.3.1. Housing and feeding

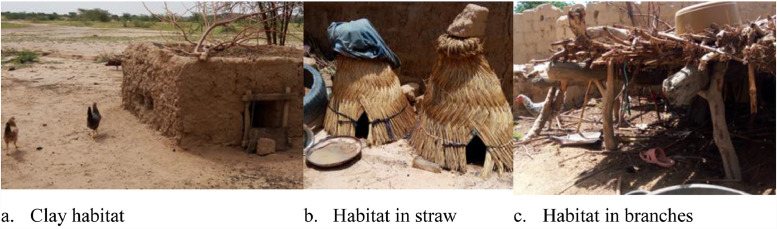

Not all producers have a particular habitat built with modern materials for their poultry. The habitats that have found with some producers (39.4%) are made of temporary materials (thatch, tree or shrub branches, clay) (Fig. 2). These habitats are most often used as dormitories for chickens. The majority of producers (88.4%) are not feeding their poultry. These poultry are forced to feed themselves by scavenging. Scavenging is the most frequent production system (92.1%) in the keeping of the local chicken in Niger (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

The different types of traditional habitat of the local chicken in Niger.

Table 3.

Housing and feeding characteristics of the local chicken in Niger.

| Parameters | Modalities | Size of samples | Frequencies (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing of local chicken | No henhouse | 131 | 60.6 |

| Traditional henhouse | 85 | 39.4 | |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | |

| Feeding | Not feeding | 191 | 88.4 |

| Dietary supplement | 25 | 11.6 | |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | |

| Production system | Intensive | 3 | 1.4 |

| Scanvenging | 199 | 92.1 | |

| Mixt | 14 | 6.5 | |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 |

3.3.2. Health management of local chicken in Niger

3.3.2.1. Symptoms of frequent diseases

The most common symptoms of Newcastle disease are diarrhea (45.32%), screaming or sometimes coughing (21.72%), prostration (19.48%) or saliva leaking from the chicken's beak (8.24%). For avian pox, the symptoms are swelling of the head (50%) or pimples that appear on the beak or in the eyes (50%). The symptoms of parasitosis are weight loss (55%), diarrhea (36.25%) and drowsiness (8.75%).

Table 4 presents the symptoms of the common diseases of the local chicken of Niger.

Table 4.

Symptoms of common diseases in Niger's local chicken.

| Symptoms | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases | Saliva flowing | Twisted neck | Diarrhea | Head is inflated | Button on the beak and/or eyes | blackish comb | Cree/cough | Drowsiness/ Prostration | emaciation | Total |

| ND (%) | 8.24 | 2.25 | 45.32 | 1.87 | - | 1.12 | 21.72 | 19.48 | - | 100 |

| Avian pox (%) | – | – | – | 50 | 50 | – | – | – | – | 100 |

| Parasitosis (%) | – | – | 36.25 | – | – | – | – | 8.75 | 55 | 100 |

ND = Newcastle disease.

3.3.2.2. Traditional treatment of frequent diseases

Avian pox (viral disease) does not have a specific medicine. Treatment is simply to deflate the wounds (100%) (Table 5). Newcastle disease is also a viral disease that has no treatment. But there is a certain proportion of producers (1.69%) who have developed a prevention technique against Newcastle disease. In fact, these producers isolate themselves with their chicken in their field during the field work. This isolation allows chickens to grow well without risk of contracting this highly contagious disease. Finally, the treatment developed against parasitosis mainly concerns external parasites or ectoparasites. Some producers use ashes (57.63%) to fight against these external parasites, others use a Dichlorvos insecticide commonly known as pia-pia (16.95%), some mix this insecticide with ash or ash with oil. To treat sick chickens, producers apply these products to their bodies.

Table 5.

Categories of traditional treatment of common diseases of the local hen of Niger.

| Traditional treatment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases | Ash | Peanut oil | Pia-pia (insecticide) | Oil and ash mixture | Pia-pia and ash mixture | Burn their local | Deflate the wounds | Migration | No treatment | Total |

| ND (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1,69 | 98,31 | 100 |

| Avian pox (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 100 | – | – | 100 |

| Parasitosis (%) | 57.63 | 8.47 | 16.95 | 3.39 | 10.17 | 3.39 | – | – | – | 100 |

ND = Newcastle disease.

3.3.2.3. Health monitoring

Among producers, only 38% vaccinate their chicken and 54.6% do not receive visits from veterinary agents at their farm. The mortality rate per year is above 50% for 94.9% of producers. For this reason, the majority of producers noted a period of inactivity of the local chicken production due to avian diseases (82.4%) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Health monitoring of Niger's local chicken.

| Parameter | Samples size | Frequencies (%) | Parameter | Samples size | Frequencies (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination of poultry | veterinary agents visit | ||||

| Yes | 82 | 38.0 | Once a week | 2 | 0.9 |

| No | 134 | 62.0 | Once a month | 20 | 9.3 |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | Once a year | 20 | 9.3 |

| Breeding inactivity period | When need | 56 | 25.9 | ||

| Yes | 178 | 82.4 | Never | 118 | 54.6 |

| No | 38 | 17.6 | Total | 216 | 100.0 |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | Mortality rate in case of diseases | ||

| Reason of breeding inactivity | <25% | 3 | 1.4 | ||

| Diseases | 178 | 82.4 | 25–50% | 8 | 3.7 |

| Non-stop | 38 | 17.6 | >50% | 205 | 94.9 |

| Total | 216 | 100.0 | Total | 216 | 100.0 |

3.4. Constraints of the breeding of the local chicken in Niger

Avian diseases constitute the largest obstacle of local chicken production for 45% of producers. Then comes the lack of habitat (16%), predators (12%), food (11%), lack of training (8%), lack of funding (4%), theft (3%) and lack of medication (1%).

Fig. 3 shows the various problems that hinder the raising of the local chicken in Niger.

Fig. 3.

Main constraints on local chicken farming in Niger.

4. Discussion

The producers of the local chicken of Niger are predominantly men. Despite the predominance of men over women in local chicken farming, it should be noted that it is women who more take care of these chickens because they are constantly at home for housework. The exceed number of producer men compare to the producer female was revealed by Loukou (2013) in Côte d'Ivoire. However, this result is contrary to that found by Fosta (2008) in Cameroon where the number of women producing the local chicken exceeds the number of men. The origin of chickens at startup is very diverse, but mostly chickens are bought. The predominance of purchase in the start-up was found by Moula, Detiffe, Farnir, Antoine-Moussiauxm and Pascal (2012) in the Democratic Republic of Congo with a proportion of 44.2%. Local chicken in Niger are mainly raised for sale, self-consumption or donation. A similar result was found by Yameogo (2003) in Burkina Faso.

Scavenging is the most widespread production system of the local chicken in Niger. In fact, only 11.6% of producers provide a dietary supplement to their chickens. These food supplements are most often cereal, remains of cooking and sometimes insects. These results from Niger confirm the reality of sub-Saharan Africa where very few farmers give compensatory feed to their chickens. The compensatory feed is quantitatively insufficient and limited to cereals or their emergence with sometimes termites (BONFOH et al., 1997, DIENG, GUEYE, MAHOUGOU-MOUELE and BULDGEN, 1998, KONARE, 2005).

The majority of producers do not have housing accommodation for their chicken in Niger. Even those who own them, the henhouses are of traditional type. Generally, these habitats are intended to house the chickens at night or to house hens with chicks. Although traditional, this type of shelter protects chickens against predators, rains or other bad weather. This result is in agreement with Boussini (1995) in Burkina Faso who showed that some producers build their henhouse with straw to house hens and their chicks at night, while the other birds spend the night on the trees.

The majority of producers do not receive visits from veterinary agents. Those who receive weekly or monthly visits are most often helped by project/NGO grants. Nevertheless, producers have developed traditional treatments for diseases. Newcastle disease, fowl pox, and parasitosis are the most common diseases in Niger. Traditional treatment of producers works more with ectoparasites and avian pox. In Zimbabwe, Mapiye and Sibanda (2005) also reported that farmers use traditional medicine to treat their chickens. This shows that traditional medicine help producer to manage some type of local chickens’ diseases. Muchadeyi, Sibanda, Kusina, Kusina, and Makuza (2005) even said that the use of traditional treatment is the most sustainable in terms of health management strategy for households. Unfortunately, much of this type of knowledge is being lost or replaced by modern methods (Gueye, 1999). It is therefore important to carry out a study to determine the methodology and use of each type of traditional treatment in order to develop a traditional poultry pharmacy.

With regard to Newcastle disease, the producers are powerless. This is why this disease is the deadliest of the poultry sector in Niger and even in many countries as Nigeria (Nwanta, Egege, Alli-Balogun, & Ezema, 2008), Botswana (Moreki, Dikeme, & Poroga, 2010) or Mauritania (Bell, Kane, & Le Jan, 1990). It is important to notify a preventive technique against Newcastle disease developed by some producers in Niger. It consists of migrating with their chickens before the beginning of the epidemic and returning on religious holidays (Ramadan or Tabaski) with a large number of poultry. This allows them to make a big profit from selling their poultry. This technique is popularized to reduce the losses caused by Newcastle disease in the poultry world.

Diseases, predators, lack of housing, training and food are the main problems that hinder the development of poultry farming in Niger. In other countries it is mainly diseases and predators that hinder poultry farming. This is the case of Nigeria (El-Yuguda, Dokas, & Baba, 2005) and Burkina Faso (Pousga, Boly, Linderberg, & Ogle, 2005). It should also be noted that the prevalence of scavenging in the poultry production system contributes significantly to increase the level of impact of these obstacles.

5. Conclusion

Chicken production plays an important role in Niger. The basis of chicken production is still traditional, which leads sometimes to total chicken losses. Epidemics are the main cause of these losses. Before thinking about a breeding program, a minimum of knowledge in the management of livestock, the supervision of livestock farmers through regular monitoring combined with prophylactic measures provided by the government would certainly improve the productivity of chicken and thus contribute to improving the living conditions of producer which are often poor populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank, The National Institute of Agronomic Research of Niger for having funded the data collection from this work, the National Committee of Ethics on Health Research for having authorized us to collect this data (authorization No.010/2017/CNERS), the various departmental and communal livestock services for valuable assistance in the selection of villages and in the conduct of investigations.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.vas.2018.11.001.

Annexe A. .

Appendix B. Supplementary materials

References

- Amadou Moussa B., Idi A., Benabdeljelil K. Aviculture familiale rurale au Niger: Alimentation et performances zootechniques. RIDAF. 2010;19(1):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfoh B., Ankers P., Pfister K., Pangui L.J., Toguebaye B.S. Proceedings international network for family poultry development workshop, M'Bour, 9-13 Décembre 1997. 1997. Répertoire de quelques contraintes de l'aviculture villageoise en Gambie et propositions de solutions pour son amélioration; pp. 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Boussini H. EISMV, Dakar, Sénégal; 1995. Contribution à l'étude des facteurs de mortalité des pintadeaux au Burkina Faso; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Bell J.G., Kane M., Le Jan C. An investigation of the disease status of village poultry in Mauritania. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 1990;8(4):291–294. [Google Scholar]

- Dieng A., Gueye E.F., Mahougou-Mouele N.M., Buldgen A. Effets de la ration et de l'espèce avicole sur la consommation alimentaire et la digestibilité des nutriments au Sénégal. Bulletin RIDAF. 1998;8:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- El-Yuguda A.D., Dokas U.M., Baba S.S. The effects of Newcastle disease and infectious bursal disease vaccines, climate and other factors on the village chicken population in North-eastern Nigeria. Journal of Food, Agriculture and Environment. 2005;3(1):55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fotsa J.C. 2008. Caractérisation des populations de poules locales (Gallus gallus) au Cameroun; p. 301. [Google Scholar]

- Gueye E.F. Ethnoveternary medicine againist poultry dieases in African villages. World's Poultry Science Journal. 1999;55:187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Konare A.M. Ecole nationale supérieure d'Agriculture; 2005. Performances et stratégies d'amélioration de l'aviculture rurale: Cas de l'expérience de VSF dans le département de Vélingara. (Mémoire de fin d’études d'ingénieur agronome) p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Mapiye C., Sibanda S. Constraints and opportunities of village chicken production systems in the smallholder sector of Rushinga District of Zimbabwe. Livestock Research Rural Development. 2005;17(10) http://www.cipav.org.co/lrrd/lrrd17/10/mapi17115.htm Acessed: 04/1l/2005. [Google Scholar]

- Muchadeyi F.C., Sibanda N.T., Kusina J.F., Kusina, Makuza S. Village chicken flock dynamics and the contribution of chickens to household livelihoods in a smallholder farming are in Zimbabwe. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 2005;37(4):333–334. doi: 10.1007/s11250-005-5082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreki J.C., Dikeme R., Poroga B. The role of village poultry in food security and HIV/AIDS mitigation in Chobe District of Botswana. Livestock Research Rural Development. 2010;22 http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd22/3/more22055.htm [Google Scholar]

- Moula N., Detiffe N., Farnir F., Antoine-Moussiaux N., Pascal L. Aviculture familiale au Bas-Congo, République Démocratique du Congo (RDC) Livestock Research for Rural Development. 2012;24 http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd24/5/moul24074.htm Retrieved January 3, 2018, from. [Google Scholar]

- N'goran Etienne Loukou . 2013. Caractérisation phénotypique et moléculaire des poules locales (gallus gallus domesticus linné, 1758) de deux zones agro-écologiques de la côte d'ivoire; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Nwanta J.A., Egege S.C., Alli-Balogun J.K., Ezema W.S. Evaluation of prevalence and seasonality of Newcastle disease in chicken in Kaduna, Nigeria. World's Poultry Science Journal. 2008;64(September(2008)):416. Odunsi. [Google Scholar]

- Pousga S., Boly H., Linderberg J.E., Ogle B. Scavenging pullets in Burkina Faso: Effect of season, location and breed on feed and nutrient intake. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2005;37:623–634. doi: 10.1007/s11250-005-4304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Republique du Niger . PANA; 2006. Programme d'action national pour l'adaptation aux changements climatiques; p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Recensement General De L'agriculture Et Du Cheptel (RGAC) 2008. Analyse des résultats des enquêtes sur les marchés à bétail et le cheptel aviaire; p. 99. Recensement général de l'agriculture et du cheptel 2005-2007. Projet GCP/NER/041/EC, MDA/MRA. [Google Scholar]

- Yameogo, N. Etude de la contribution de l'aviculture traditionnelle urbaine et péri-urbaine dans la lutte contre les pathologies aviaires au Burkina Faso. Université de Ouagadougou, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, UFR/SVT, IDRC, Rapport AGROPOLIS, 2003.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.