Abstract

Background

Some people with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection remain asymptomatic, whilst in others the infection can cause mild to moderate COVID‐19 disease and COVID‐19 pneumonia, leading some patients to require intensive care support and, in some cases, to death, especially in older adults. Symptoms such as fever or cough, and signs such as oxygen saturation or lung auscultation findings, are the first and most readily available diagnostic information. Such information could be used to either rule out COVID‐19 disease, or select patients for further diagnostic testing.

Objectives

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of signs and symptoms to determine if a person presenting in primary care or to hospital outpatient settings, such as the emergency department or dedicated COVID‐19 clinics, has COVID‐19 disease or COVID‐19 pneumonia.

Search methods

On 27 April 2020, we undertook electronic searches in the Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register and the University of Bern living search database, which is updated daily with published articles from PubMed and Embase and with preprints from medRxiv and bioRxiv. In addition, we checked repositories of COVID‐19 publications. We did not apply any language restrictions.

Selection criteria

Studies were eligible if they included patients with suspected COVID‐19 disease, or if they recruited known cases with COVID‐19 disease and controls without COVID‐19. Studies were eligible when they recruited patients presenting to primary care or hospital outpatient settings. Studies including patients who contracted SARS‐CoV‐2 infection while admitted to hospital were not eligible. The minimum eligible sample size of studies was 10 participants. All signs and symptoms were eligible for this review, including individual signs and symptoms or combinations. We accepted a range of reference standards including reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR), clinical expertise, imaging, serology tests and World Health Organization (WHO) or other definitions of COVID‐19.

Data collection and analysis

Pairs of review authors independently selected all studies, at both title and abstract stage and full‐text stage. They resolved any disagreements by discussion with a third review author. Two review authors independently extracted data and resolved disagreements by discussion with a third review author. Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias using the QUADAS‐2 checklist. Analyses were descriptive, presenting sensitivity and specificity in paired forest plots, in ROC (receiver operating characteristic) space and in dumbbell plots. We did not attempt meta‐analysis due to the small number of studies, heterogeneity across studies and the high risk of bias.

Main results

We identified 16 studies including 7706 participants in total. Prevalence of COVID‐19 disease varied from 5% to 38% with a median of 17%. There were no studies from primary care settings, although we did find seven studies in outpatient clinics (2172 participants), and four studies in the emergency department (1401 participants). We found data on 27 signs and symptoms, which fall into four different categories: systemic, respiratory, gastrointestinal and cardiovascular. No studies assessed combinations of different signs and symptoms and results were highly variable across studies. Most had very low sensitivity and high specificity; only six symptoms had a sensitivity of at least 50% in at least one study: cough, sore throat, fever, myalgia or arthralgia, fatigue, and headache. Of these, fever, myalgia or arthralgia, fatigue, and headache could be considered red flags (defined as having a positive likelihood ratio of at least 5) for COVID‐19 as their specificity was above 90%, meaning that they substantially increase the likelihood of COVID‐19 disease when present.

Seven studies carried a high risk of bias for selection of participants because inclusion in the studies depended on the applicable testing and referral protocols, which included many of the signs and symptoms under study in this review. Five studies only included participants with pneumonia on imaging, suggesting that this is a highly selected population. In an additional four studies, we were unable to assess the risk for selection bias. These factors make it very difficult to determine the diagnostic properties of these signs and symptoms from the included studies.

We also had concerns about the applicability of these results, since most studies included participants who were already admitted to hospital or presenting to hospital settings. This makes these findings less applicable to people presenting to primary care, who may have less severe illness and a lower prevalence of COVID‐19 disease. None of the studies included any data on children, and only one focused specifically on older adults. We hope that future updates of this review will be able to provide more information about the diagnostic properties of signs and symptoms in different settings and age groups.

Authors' conclusions

The individual signs and symptoms included in this review appear to have very poor diagnostic properties, although this should be interpreted in the context of selection bias and heterogeneity between studies. Based on currently available data, neither absence nor presence of signs or symptoms are accurate enough to rule in or rule out disease. Prospective studies in an unselected population presenting to primary care or hospital outpatient settings, examining combinations of signs and symptoms to evaluate the syndromic presentation of COVID‐19 disease, are urgently needed. Results from such studies could inform subsequent management decisions such as self‐isolation or selecting patients for further diagnostic testing. We also need data on potentially more specific symptoms such as loss of sense of smell. Studies in older adults are especially important.

Plain language summary

Can symptoms and medical examination accurately diagnose COVID‐19 disease?

COVID‐19 is an infectious disease caused by the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus. Most people with COVID‐19 have a mild to moderate respiratory illness; others experience severe illness, such as COVID‐19 pneumonia. Formal diagnosis requires laboratory analysis of nose and throat samples, or imaging tests like CT scans. However, the first and most accessible diagnostic information is from symptoms and signs from clinical examination. If initial diagnosis by symptoms and signs were accurate, the need for time‐consuming, specialist diagnostic tests would be reduced.

Symptoms are experienced by patients. People with mild COVID‐19 might experience cough, sore throat, high temperature, diarrhoea, headache, muscle or joint pain, fatigue, and loss of sense of smell and taste. Symptoms of COVID‐19 pneumonia include breathlessness, loss of appetite, confusion, pain or pressure in the chest, and high temperature (above 38 °C).

Signs are evaluated by clinical examination, and include lung sounds, blood pressure and heart rate.

Often, people with mild symptoms visit their doctor (primary care physician) for an initial diagnosis. People with more severe symptoms might visit a hospital outpatient or emergency department. Depending on their symptoms and signs, patients may be sent home to isolate, may receive further tests or be hospitalised.

Why is accurate diagnosis important?

Accurate diagnosis ensures that people receive the correct treatment quickly; are not tested, treated or isolated unnecessarily; and do not risk spreading COVID‐19. This is important for individuals and saves time and resources.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to know how accurate diagnosis of COVID‐19 and COVID‐19 pneumonia is in a primary care or hospital setting, based on symptoms and signs from medical examination.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that assessed the accuracy of symptoms and signs to diagnose mild COVID‐19 and COVID‐19 pneumonia. Studies could include people with possible COVID‐19, or people known to have – and not to have – COVID‐19. Studies had to be in primary care or hospital outpatient settings only and include at least 10 participants with any symptom or sign that might be COVID‐19.

The included studies

We found 16 relevant studies with 7706 participants. The studies assessed 27 separate signs and symptoms, but none assessed combinations of signs and symptoms. Seven were set in hospital outpatient clinics (2172 participants), four in emergency departments (1401 participants), but none in primary care settings. No studies included children, and only one focused on older adults. All the studies confirmed COVID‐19 diagnosis by the most accurate tests available.

Main results

The studies did not clearly distinguish mild to moderate COVID‐19 from COVID‐19 pneumonia, so we present the results for both conditions together.

The results indicate that at least half of participants with COVID‐19 disease had a cough, sore throat, high temperature, muscle or joint pain, fatigue, or headache. However, cough and sore throat were also common in people without COVID‐19, so these symptoms alone are less helpful for diagnosing COVID‐19. High temperature, muscle or joint pain, fatigue, and headache substantially increase the likelihood of COVID‐19 disease when they are present.

How reliable are the results?

The accuracy of individual symptoms and signs varied widely across studies. Moreover, the studies selected participants in a way that meant the accuracy of tests based on symptoms and signs may be uncertain.

Conclusions

All studies were conducted in hospital outpatient settings, so the results are not representative of primary care settings. The results do not apply to children or older adults specifically, and do not clearly differentiate between milder COVID‐19 disease and COVID‐19 pneumonia.

The results suggest that a single symptom or sign included in this review cannot accurately diagnose COVID‐19. Doctors base diagnosis on multiple symptoms and signs, but the studies did not reflect this aspect of clinical practice.

Further research is needed to investigate combinations of symptoms and signs; symptoms that are likely to be more specific, such as loss of sense of smell; and testing unselected populations, in primary care settings and in children and older adults.

How up to date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies published from January to April 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Signs and symptoms to determine if a patient presenting in primary care or outpatient hospital setting has COVID‐19 disease.

| Sign or symptom | Study design | Setting | Number of studies/number of participants | Sensitivity (ranges) | Specificity (ranges) |

Strength of evidence Number of studies with high risk of bias per QUADAS‐2 domain: participant selection/index test/reference standard/flow and timing |

| Cough | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 7/2554 | 0.43 to 0.71 | 0.14 to 0.54 | 3/7/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/53 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/262 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 2/170 | 0.47 to 0.69 | 0.15 to 0.20 | 2/1/0/0 | ||

| Sputum production | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 6/2467 | 0.16 to 0.33 | 0.50 to 0.86 | 3/6/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Dyspnoea | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 7/2554 | 0.00 to 0.25 | 0.82 to 0.98 | 3/7/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/262 | 0.12 | 0.77 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Hypoxia | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/2929b | 0.15 | 0.83 | 0/0/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Haemoptysis | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/116 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Positive auscultation findings | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/788 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/34 | 0.11 | 0.67 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Respiratory symptoms (not otherwise specified) | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/788 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Sore throat | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 6/2438 | 0.05 to 0.71 | 0.55 to 0.80 | 3/6/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/262 | 0.17 | 0.55 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 2/170 | 0.13 to 0.21 | 0.73 to 0.91 | 2/1/0/0 | ||

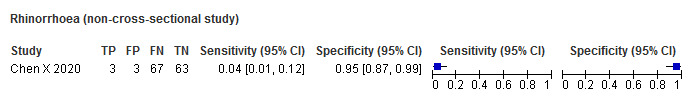

| Nasal symptoms | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 5/2405 | 0.00 to 0.22 | 0.69 to 0.92 | 2/5/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/262 | 0.19 | 0.79 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/136 | 0.03 for nasal obstruction 0.04 for rhinorrhoea |

0.94 for nasal obstruction 0.95 for rhinorrhoea |

1/0/0/0 | ||

| Loss of sense of smell or taste | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/870 | 0.23 | 0.99 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/262 | 0.22 for smell 0.20 for taste |

0.96 for smell 0.95 for taste |

0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Fever | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 8/5315 | 0.07 to 0.93 | 0.16 to 0.94 | 2/7/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/53 | 0.80 | 0.48 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/262 | 0.54 | 0.74 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/34 | 0.79 | 0.07 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Low body temperature | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/2929b | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0/0/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Shivers | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/132 | 0.14 | 0.86 | 0/1/1/1 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Chills | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 2/1443 | 0.07 to 0.29 | 0.72 to 0.91 | 0/2/1/1 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Myalgia or arthralgia | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 4/339 | 0.19 to 0.86 | 0.45 to 0.91 | 2/4/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/262 | 0.34 | 0.81 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Myalgia or fatigue | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 2/1427 | 0.16 to 0.31 | 0.82 to 0.93 | 0/2/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Fatigue | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 2/220 | 0.43 to 0.57 | 0.60 to 0.67 | 1/2/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/53 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/262 | 0.42 | 0.69 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 2/170 | 0.11 to 0.31 | 0.88 to 1.00 | 2/1/0/0 | ||

| Headache | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 4/1647 | 0.03 to 0.71 | 0.78 to 0.98 | 1/4/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/53 | 0.15 | 0.97 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 2/436 | 0.00 to 0.04 | 0.97 to 0.97 | 0/2/1/1 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/53 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 2/778 | 0.05 to 0.23 | 0.81 to 0.96 | 0/2/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Diarrhoea | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 5/1680 | 0.00 to 0.14 | 0.86 to 0.99 | 2/5/1/2 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/53 | 0.15 | 0.88 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 2/778 | 0.08 to 0.20 | 0.85 to 0.92 | 0/2/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/34 | 0.05 | 0.93 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Abdominal pain | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/132 | 0.00 | 0.96 | 0/1/1/1 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/53 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/788 | 0.37 | 0.68 | 1/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/516 | 0.35 | 0.74 | 0/1/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

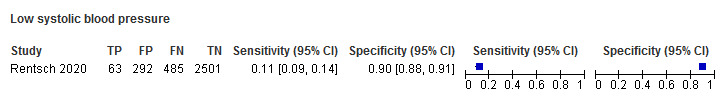

| Low systolic blood pressure | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/3341b | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0/0/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| High systolic blood pressure | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/3341 | 0.39 | 0.57 | 0/0/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Tachycardia | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/3373 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0/0/0/0 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Palpitations | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | 1/132 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0/1/1/1 | ||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Chest tightness | Cross‐sectional | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Hospital outpatient clinics | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Hospital inpatientsa | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Case‐control | Primary care | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ||

| Hospital outpatient clinics | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Hospital inpatientsa | 1/34 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 1/1/0/0 |

a'Hospital inpatients' refers to studies that recruited patients admitted to hospital with COVID‐19 disease and in whom the signs and symptoms were assessed on admission. bSetting not specified; assumed hospital outpatients considering the timing in the epidemic and sparse testing capacity outside hospitals at the time (Rentsch 2020).

Background

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) and resulting COVID‐19 pandemic present important diagnostic evaluation challenges. These range from, on the one hand, understanding the value of signs and symptoms in predicting possible infection, assessing whether existing biochemical and imaging tests can identify infection and recognise patients needing critical care, and on the other hand, evaluating whether new diagnostic tests can allow accurate rapid and point‐of‐care testing. Also, the diagnostic aims are diverse, including identifying current infection, ruling out infection, identifying people in need of care escalation, or testing for past infection.

This review is part of a cluster of reviews on the diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19 disease, and deals solely with the diagnostic accuracy of presenting clinical signs and symptoms for diagnosing COVID‐19 disease.

Target condition being diagnosed

COVID‐19 is the disease caused by infection with the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is diagnosed with reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR), which is a test that detects the virus' genetic material, with imaging to identify lung abnormalities and with clinical signs and symptoms.

SARS‐CoV‐2 infection can be asymptomatic (no symptoms); mild or moderate; severe (causing breathlessness and increased respiratory rate indicative of pneumonia and oxygen need); or critical (requiring intensive support due to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), shock or other organ dysfunction). People with COVID‐19 pneumonia (severe or critical disease), require different patient management, which makes it important to distinguish between mild or moderate COVID‐19 disease and COVID‐19 pneumonia.

In this review, we will examine the diagnostic value of signs and symptoms for symptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, which includes mild or moderate COVID‐19 disease and COVID‐19 pneumonia.

In planning review updates, we will consider the potential addition of another grouping, which is a subset of the above:

whether tests exist that identify people requiring respiratory support (SARS or ARDS) or intensive care.

Index test(s)

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms are used in the initial diagnosis of suspected COVID‐19 disease, and to identify people with COVID‐19 pneumonia. Symptoms are what is experienced by patients, for example cough or nausea. Signs are what can be evaluated by clinical assessment, for example lung auscultation findings, blood pressure or heart rate.

Key symptoms that have been associated with mild to moderate COVID‐19 disease include: troublesome dry cough (for example, coughing more than usual over a one‐hour period, or three or more coughing episodes in 24 hours), fever greater than 37.8 °C, diarrhoea, headache, breathlessness on light exertion, muscle pain, fatigue, and loss of sense of smell and taste. Red flags indicating possible pneumonia include breathlessness at rest, loss of appetite, confusion, pain or pressure in the chest, and temperature above 38 °C.

Clinical pathway

Important in the context of COVID‐19 is that the pathway is multifaceted because it is designed to care for the diseased individual and to protect the community from further spread. Decisions about patient and isolation pathways for COVID‐19 vary according to health services and settings, available resources, and stages of the epidemic. They will change over time, if and when effective treatments and vaccines are identified. The decision points between these pathways vary, but all include points at which knowledge of the accuracy of diagnostic information is needed to be able to inform rational decision making.

Prior test(s)

In this review on signs and symptoms, no prior tests are required because signs and symptoms are used in the initial diagnosis of suspected COVID‐19 disease. Patients can, however, self‐assess before presenting to healthcare services based on their symptoms. This is in contrast to contact tracing, in which patients or participants are tested based on a documented contact with a SARS‐CoV‐2‐positive person and may themselves be asymptomatic.

Role of index test(s)

Signs and symptoms are used as triage tests, that is, to rule out COVID‐19 disease, but also to identify patients with possible COVID‐19 who may require further testing, care escalation or isolation.

Alternative test(s)

Chest X‐ray, ultrasound, and computed tomography (CT) are widely used diagnostic imaging tests to diagnose COVID‐19 pneumonia. Availability and usage varies between settings. We address these radiological tests in a separate review.

Rationale

It is essential to understand the accuracy of diagnostic tests including signs and symptoms to identify the best way they can be used in different settings to develop effective diagnostic and management pathways. We are producing a suite of Cochrane 'living systematic reviews', which will summarise evidence on the clinical accuracy of different tests and diagnostic features, grouped according to present research questions and settings, in the diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19 disease. Summary estimates of accuracy from these reviews will help inform diagnostic, screening, isolation, and patient management decisions.

New tests are being developed and evidence is emerging at an unprecedented rate during the COVID‐19 pandemic. We will aim to update these reviews as often as is feasible to ensure that they provide the most up‐to‐date evidence about test accuracy.

These reviews are being produced rapidly to assist in providing a central resource of evidence to assist in the COVID‐19 pandemic, summarising available evidence on the accuracy of the tests and presenting characteristics.

Objectives

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of signs and symptoms to determine if a person presenting in primary care or to hospital outpatient settings, such as the emergency department or dedicated COVID‐19 clinics, has COVID‐19 disease or COVID‐19 pneumonia.

Secondary objectives

Where data are available, we will investigate diagnostic accuracy (either by stratified analysis or meta‐regression) according to:

days since symptom onset, population (children; older adults), reference standard, study design, setting, severity of COVID‐19 pneumonia (severe COVID‐19 pneumonia/ARDS requiring intensive care support).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We kept the eligibility criteria purposely broad to include all patient groups and all variations of a test at this initial stage of reviewing the evidence (that is, if the patient population was unclear, we included the study).

We included studies of all designs that produce estimates of test accuracy or provide data from which estimates can be computed. We included both single‐gate (studies that recruit from a patient pathway before disease status has been ascertained) and multi‐gate (where people with and without the target condition are recruited separately) designs. This means that we included studies that were cross‐sectional or diagnostic case‐control type studies.

When interpreting the results, we made sure that the limitations of different study designs were carefully considered, using quality assessment and analysis.

Participants

Studies recruiting people presenting to primary care or outpatient hospital settings with suspicion of COVID‐19 disease were eligible.

For the initial version of this review, we included studies that recruited symptomatic people either known to have SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or known not to have SARS‐CoV‐2 infection.

Studies had to have a sample size of a minimum of 10 participants.

Index tests

-

All signs and symptoms, including:

signs such as oxygen saturation, measured by oximetry or blood pressure;

classic symptoms, such as fever or cough.

We included combinations of signs and symptoms, but not when they were combined with laboratory, imaging, or other types of index tests as these will be covered in the other reviews.

Target conditions

To be eligible studies had to identify at least one of:

mild or moderate COVID‐19 disease;

COVID‐19 pneumonia.

Asymptomatic infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is out of scope for this review, considering it is by definition not possible to detect this based on signs and symptoms.

Reference standards

We anticipated that studies would use a range of reference standards. Although RT‐PCR is considered the best available test, due to rapidly evolving knowledge about the target conditions, multiple reference standards on their own as well as in combination have emerged.

We expected to encounter cases defined by:

RT‐PCR alone;

RT‐PCR, clinical expertise, and imaging (for example, CT thorax);

repeated RT‐PCR several days apart or from different samples;

plaque reduction neutralisation test (PRNT) or enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay(ELISA) tests;

information available at a subsequent time point;

World Health Organization (WHO) and other case definitions (see Appendix 1).

This list is not exhaustive, and we recorded all reference standards encountered. With a group of methodological and clinical experts, we are producing a ranking of reference standards according to their ability to correctly classify participants using a consensus process. We will use the ranking for informing the assessment of methodological quality in the next update of this review.

Search methods for identification of studies

The final search date for this version of the review is 27 April 2020.

Electronic searches

We conducted a single literature search to cover our suite of Cochrane COVID‐19 diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) reviews (Deeks 2020; McInnes 2020).

We conducted electronic searches using two primary sources. Both of these searches aimed to identify all published articles and preprints related to COVID‐19, and were not restricted to those evaluating biomarkers or tests. Thus, there are no test terms, diagnosis terms, or methodological terms in the searches. Searches were limited to 2019 and 2020, and for this version of the review have been conducted to 27 April 2020.

Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register searches

We used the Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register (covid-19.cochrane.org/), for searches conducted to 28 March 2020. At that time, the register was populated by searches of PubMed, as well as trials registers at ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP).

Search strategies were designed for maximum sensitivity, to retrieve all human studies on COVID‐19 and with no language limits. See Appendix 2.

COVID‐19 Living Evidence Database from the University of Bern

From 28 March 2020, we used the COVID‐19 Living Evidence database from the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM) at the University of Bern (www.ispm.unibe.ch), as the primary source of records for the Cochrane COVID‐19 DTA reviews. This search includes PubMed, Embase, and preprints indexed in bioRxiv and medRxiv databases. The strategies as described on the ISPM website are described here (ispmbern.github.io/covid-19/). See Appendix 3.

The decision to focus primarily on the 'Bern' feed was due to the exceptionally large numbers of COVID‐19 studies available only as preprints. The Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register has undergone a number of iterations since the end of March 2020 and we anticipate moving back to the Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register as the primary source of records for subsequent review updates.

Searching other resources

We obtained Embase records through Martha Knuth for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Stephen B Thacker CDC Library, COVID‐19 Research Articles Downloadable Database and de‐duplicated them against the Cochrane COVID‐19 Study Register up to 1 April 2020. See Appendix 4.

We also checked our search results against two additional repositories of COVID‐19 publications including:

the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co‐ordinating Centre (EPPI‐Centre) 'COVID‐19: Living map of the evidence' (eppi.ioe.ac.uk/COVID19_MAP/covid_map_v4.html);

the Norwegian Institute of Public Health 'NIPH systematic and living map on COVID‐19 evidence' (www.nornesk.no/forskningskart/NIPH_diagnosisMap.html)

Both of these repositories allow their contents to be filtered according to studies potentially relating to diagnosis, and both have agreed to provide us with updates of new diagnosis studies added. For this iteration of the review, we examined all diagnosis studies from both sources up to 16 April 2020.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Pairs of review authors independently screened studies. We resolved disagreements by discussion with a third, experienced review author for initial title and abstract screening, and through discussion between three review authors for eligibility assessments.

Data extraction and management

Pairs of review authors independently performed data extraction. We resolved disagreements by discussion between three review authors.

We intended to contact study authors where we needed to clarify details or obtain missing information.

Assessment of methodological quality

Pairs of review authors independently assessed risk of bias and applicability concerns using the QUADAS‐2 (Quality Assessment tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies) checklist, which was common to the suite of reviews but tailored to each particular review (Whiting 2011; Table 2). For this review, we excluded the questions on the nature of the samples as these were not relevant, and we added a question on who assessed the signs. We resolved disagreements by discussion between three review authors.

1. QUADAS‐2 checklist.

| Index test(s) | Signs and symptoms |

| Patients (setting, intended use of index test, presentation, prior testing) | Primary care, hospital outpatient settings including emergency departments Inpatients presenting with suspected COVID‐19 No prior testing Signs and symptoms often used for triage or referral |

| Reference standard and target condition | The focus will be on the diagnosis of COVID‐19 disease and COVID‐19 pneumonia. For this review, the focus will not be on prognosis. |

| Participant selection | |

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | This will be similar for all index tests, target conditions, and populations. YES: if a study explicitly stated that all participants within a certain time frame were included; that this was done consecutively; or that a random selection was done. NO: if it was clear that a different selection procedure was employed; for example, selection based on clinician's preference, or based on institutions. UNCLEAR: if the selection procedure was not clear or not reported. |

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | This will be similar for all index tests, target conditions, and populations. YES: if a study explicitly stated that all participants came from the same group of (suspected) patients. NO: if it was clear that a different selection procedure was employed for the participants depending on their COVID‐19 (pneumonia) status or SARS‐CoV‐2 infection status. UNCLEAR: if the selection procedure was not clear or not reported. |

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | Studies may have excluded participants, or selected participants in such a way that they avoided including those who were difficult to diagnose or likely to be borderline. Although the inclusion and exclusion criteria will be different for the different index tests, inappropriate exclusions and inclusions will be similar for all index tests: for example, only elderly patients excluded, or children (as sampling may be more difficult). This needs to be addressed on a case‐by‐case basis. YES: if a high proportion of eligible patients was included without clear selection. NO: if a high proportion of eligible patients was excluded without providing a reason; if, in a retrospective study, participants without index test or reference standard results were excluded; if exclusion was based on severity assessment post‐factum or comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, immunosuppression). UNCLEAR: if the exclusion criteria were not reported. |

| Did the study avoid inappropriate inclusions? | YES: if samples included were likely to be representative of the spectrum of disease. NO: if the study oversampled patients with particular characteristics likely to affect estimates of accuracy. UNCLEAR: if the exclusion criteria were not reported. |

| Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? | HIGH: if one or more signalling questions were answered with NO, as any deviation from the selection process may lead to bias. LOW: if all signalling questions were answered with YES. UNCLEAR: all other instances. |

| Is there concern that the included patients do not match the review question? | HIGH: if accuracy of signs and symptoms were assessed in a case‐control design, or in an already highly selected group of participants, or the study was able to only estimate sensitivity or specificity. LOW: any situation where signs and symptoms were the first assessment/test to be done on the included participants. UNCLEAR: if a description about the participants was lacking. |

| Index tests | |

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | This will be similar for all index tests, target conditions, and populations. YES: if blinding was explicitly stated or index test was recorded before the results from the reference standard were available. NO: if it was explicitly stated that the index test results were interpreted with knowledge of the results of the reference standard. UNCLEAR: if blinding was unclearly reported. |

| If a threshold was used, was it prespecified? | This will be similar for all index tests, target conditions, and populations. YES: if the test was dichotomous by nature, or if the threshold was stated in the methods section, or if authors stated that the threshold as recommended by the manufacturer was used. NO: if a receiver operating characteristic curve was drawn or multiple threshold reported in the results section; and the final result was based on one of these thresholds; if fever was not defined beforehand. UNCLEAR: if threshold selection was not clearly reported. |

| Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? | HIGH: if one or more signalling questions were answered with NO, as even in a laboratory situation knowledge of the reference standard may lead to bias. LOW: if all signalling questions were answered with YES. UNCLEAR: all other instances. |

| Is there concern that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? | This will probably be answered 'LOW' in all cases except when assessments were made in a different setting, or using personnel not available in practice. |

| Reference standard | |

| Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? | We will define acceptable reference standards using a consensus process once the list of reference standards that have been used has been obtained from the eligible studies. For severe pneumonia, we will consider how well processes adhered to the WHO case definition in Appendix 1. |

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? | YES: if it was explicitly stated that the reference standard results were interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test, or if the result of the index test was obtained after the reference standard. NO: if it was explicitly stated that the reference standard results were interpreted with knowledge of the results of the index test or if the index test was used to make the final diagnosis. UNCLEAR: if blinding was unclearly reported. |

| Did the definition of the reference standard incorporate results from the index test(s)? | YES: if results from the index test were a component of the reference standard definition. NO: if the reference standard did not incorporate the index standard test. UNCLEAR: if it was unclear whether the results of the index test formed part of the reference standard. |

| Could the conduct or interpretation of the reference standard have introduced bias? | HIGH: if one or more signalling questions were answered with NO. LOW: if all signalling questions were answered with YES. UNCLEAR: all other instances. |

| Is there concern that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? | HIGH: if the target condition was COVID‐19 pneumonia, but only RT‐PCR was used; if alternative diagnosis was highly likely and not excluded (will happen in paediatric cases, where exclusion of other respiratory pathogens is also necessary); if tests used to follow up viral load in known test‐positives. LOW: if above situations were not present. UNCLEAR: if intention for testing was not reported in the study. |

| Flow and timing | |

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? | YES: this will be similar for all index tests, populations for the current infection target conditions: as the situation of a patient, including clinical presentation and disease progress, evolves rapidly and new/ongoing exposure can result in case status change, an appropriate time interval will be within 24 hours. NO: if there was more than 24 hours between the index test and the reference standard or if participants were otherwise reported to be assessed with the index versus reference standard test at moments of different severity. UNCLEAR: if the time interval was not reported. |

| Did all patients receive a reference standard? | YES: if all participants received a reference standard (clearly no partial verification). NO: if only (part of) the index test‐positives or index test‐negatives received the complete reference standard. UNCLEAR: if it was not reported. |

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | YES: if all participants received the same reference standard (clearly no differential verification). NO: if (part of) the index test‐positives or index test‐negatives received a different reference standard. UNCLEAR: if it was not reported. |

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | YES: if all included participants were included in the analyses. NO: if after the inclusion/exclusion process, participants were removed from the analyses for different reasons: no reference standard done, no index test done, intermediate results of both index test or reference standard, indeterminate results of both index test or reference standard, samples unusable. UNCLEAR: if this was not clear from the reported numbers. |

| Could the patient flow have introduced bias? | HIGH: if one or more signalling questions were answered with NO. LOW: if all signalling questions were answered with YES. UNCLEAR: all other instances. |

| ICU: intensive care unit; RT‐PCR: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SARS‐CoV‐2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WHO: World Health Organization | |

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

We present results of estimated sensitivity and specificity using paired forest plots and summarised in tables as appropriate.

We present the results without meta‐analysis, due to the small numbers of studies currently available, considerable heterogeneity across studies and the high risk of bias that we identified, as we felt doing so would otherwise produce a seemingly more accurate estimate than the underlying evidence is able to provide at this moment in time.

We present results of estimated sensitivity and specificity using paired forest plots in Review Manager 2014, and dumbbell plots to display the change in disease probability after a positive or negative result.

We disaggregated data by study design and organised by target condition, reporting results from cross‐sectional studies separately from studies that used a diagnostic case‐control or other design that we assessed as prone to high risk of bias.

When pooling does become possible in a future update of this review, we will estimate mean sensitivity and specificity using hierarchical models where tests either report binary results or at commonly reported thresholds. Where data are sparse, we will use methods described by Takwoingi 2017 for obtaining estimates from simplified models. We anticipate that over time sufficient data will accumulate to provide clear estimates of test accuracy for some tests. We will undertake meta‐analysis in STATA version 16.0 (STATA), or SAS (SAS 2015), as detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy (Chapter 10; Macaskill 2013).

Investigations of heterogeneity

We have listed sources of heterogeneity that we investigated if adequate data were available in the Secondary objectives. In this version of the review, we used stratification to investigate heterogeneity as we considered it was inappropriate to combine studies. In future updates, if meta‐analysis becomes possible, we will investigate heterogeneity through meta‐regression.

We will stratify by reference standard and study design. In this version of the review we have stratified by study design only, as stratification by reference standard was not yet possible.

Sensitivity analyses

We aimed to undertake sensitivity analyses considering the impact of:

unpublished studies;

studies with inadequate reference standards.

However, neither were possible in this version of the review.

Assessment of reporting bias

We aimed to publish lists of studies that we know exist but for which we have not managed to locate reports, and request information to include in updates of these reviews. However, at the time of writing this version of the review, we are unaware of unpublished studies.

Summary of findings

We have listed our key findings in a 'Summary of findings' table to determine the strength of evidence for each test and findings, and to highlight important gaps in the evidence.

Updating

We will undertake the searches of published literature and preprints bi‐weekly, and, dependent on the number of new and important studies found, we will consider updating each review with each search if resources allow.

Results

Results of the search

The search yielded 10,965 records after removing duplicates. The first selection resulted in 658 records that were potentially eligible for this review on signs and symptoms. After screening on title and abstract, we excluded 457 records, leaving 201 to be assessed on full text. Of these, we included 16 studies in this review. The reasons for excluding 185 records are listed in the PRISMA flow chart (see Figure 1; Moher 2009).

1.

Flow diagram

Two studies reported on the same cases while using a different control group (Chen X 2020; Yang 2020d). Chen X 2020 used a concurrent control group of pneumonia cases negative for SARS‐CoV‐2 on PCR testing but Yang 2020d used a historic control group of influenza pneumonia patients. For this reason we only included the Chen X 2020 results in the analyses.

One study reported a study that included a derivation and validation part for the development of a prediction rule (Song 2020b). The two parts are identical in set‐up and only differ in respect to the time of data collection, that is, the derivation part recruited participants up to 5 February 2020 and the validation part recruited participants from 6 February 2020 onwards. As a result, we consider this to be one study and have entered all data on signs and symptoms as such.

Four studies were conducted in the USA, all other studies were from China. A summary of the main study characteristics can be found in Table 3.

2. Summary of study characteristics.

| Study ID | Target condition | Sample size | Prevalence | Setting | Population | Design | Reference standard |

| Ai 2020a | COVID‐19 pneumonia | 53 | 38% | Hospital inpatientsa | Patients hospitalised with pneumonia diagnosed by imaging | Cross‐sectional | PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs |

| Chen X 2020 | COVID‐19 pneumonia | 136 | Not applicable | Hospital inpatientsa | Patients admitted with pneumonia | Cases selected cross‐sectionally in 5 hospitals, non‐cases from 1 hospital only | PCR, samples not specified |

| Cheng 2020a | COVID‐19 pneumonia | 33 | 33% | Hospital outpatients | Patients presenting to a fever observation department with pneumonia | Cross‐sectional | PCR on throat swabs |

| Feng 2020a | COVID‐19 pneumonia | 132 | 5% | Emergency department | Patients presenting to fever clinic of emergency department | Cross‐sectional | PCR on throat swabs |

| Liang 2020 | COVID‐19 pneumonia | 88 | 24% | Hospital outpatients | Patients with pneumonia and presenting to fever clinic | Cross‐sectional | PCR, sample not specified; conducted after panel discussion |

| Nobel 2020 | COVID‐19 disease | 516 | Not applicable | Hospital outpatients | Patients who underwent SARS‐CoV‐2 testing with intent to hospitalise or in essential personnel | Case‐control | PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs |

| Peng 2020a | COVID‐19 disease | 86 | 13% | Hospital outpatients | Patients clinically suspected and referred for testing | Cross‐sectional | PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs |

| Rentsch 2020 | COVID‐19 disease | 3789 | 15% | Unclear | Patients tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 in the Veterans Affairs Cohort born between 1945 and 1965 | Cross‐sectional | PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs |

| Song 2020b | COVID‐19 disease | 399 | 7% | Hospital outpatients | Patients tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 | Cross‐sectional | PCR on sputum samples |

| Sun 2020a | COVID‐19 disease | 788 | 7% | Hospital outpatients | Patients presenting to testing centre, either self‐referred, referred from primary care or at‐risk cases identified by national contact tracing | Cross‐sectional | PCR on sputum, endotracheal aspirate, nasopharyngeal swabs or throat swabs |

| Tolia 2020 | COVID‐19 disease | 283 | 10% | Emergency department | Patients presenting with symptoms, travel history, risk factors or healthcare workers | Cross‐sectional | PCR on nasopharyngeal swabs |

| Wee 2020 | COVID‐19 disease | 870 | 18% | Emergency department | Patients presenting with respiratory symptoms or travel history | Cross‐sectional | PCR on oropharyngeal swabs |

| Yan 2020a | COVID‐19 disease | 262 | 23% | Hospital outpatient | Patients presenting hospital for SARS‐CoV‐2 testing, not otherwise specified | Internet survey after presentation | PCR, samples not specified |

| Yang 2020d | COVID‐19 pneumonia | 121 | Not applicable | Hospital inpatientsa | Patient with pneumonia from SARS‐CoV‐2 and patients with pneumonia from influenza in 2015‐2019 | Case‐control | PCR, samples not specified |

| Zhao 2020a | COVID‐19 pneumonia | 34 | Not applicable | Hospital inpatientsa | Patients with pneumonia and admitted to hospital | Case‐control | PCR on throat or sputum swabs |

| Zhu 2020b | COVID‐19 disease | 116 | 28% | Emergency department | Patients suspected of SARS‐CoV‐2 and presenting to the emergency department | Cross‐sectional | PCR, samples not specified |

| PCR: polymerase chain reaction; SARS‐CoV‐2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 | |||||||

a'Hospital inpatients' refers to studies that recruited patients admitted to hospital with COVID‐19 disease and in whom the signs and symptoms were assessed on admission.

Methodological quality of included studies

The results of the quality assessment are summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3. We rated participant selection as introducing high risk of bias in seven studies. In five studies this was because a CT scan or other imaging was used to diagnose patients with pneumonia prior to inclusion in the study, leading to a highly selected patient population (Ai 2020a; Chen X 2020; Cheng 2020a; Liang 2020; Yang 2020d); RT‐PCR results were subsequently used to distinguish between COVID‐19 pneumonia and pneumonia from other causes. For all studies, testing was highly dependent on the local case definition and testing criteria that were in effect at the time of the study, meaning all patients that were included in studies had already gone through a referral/selection filter, which was not always described. The most extreme example of this is the study by Liang 2020, in which patients with radiological evidence of pneumonia and a clinical presentation compatible with COVID‐19 were only tested for SARS‐CoV‐2 after a panel discussion.

2.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies

3.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns summary: review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study

Of the 16 studies included in this first version of the review, five studies did not use a cross‐sectional design. Three studies were diagnostic case‐control studies (Nobel 2020; Yang 2020d; Zhao 2020a), one study selected cases cross‐sectionally in five hospitals but only selected cases in one hospital (Chen X 2020), and one study emailed patients who had undergone testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 about olfactory symptoms prior to the SARS‐CoV‐2 test, with a response rate of 58% in SARS‐CoV‐2 positive cases and 15% in negative cases (Yan 2020a).

We rated all studies except two as carrying a high risk of bias for the index tests because there was little to no detail on how, by whom, and when the signs and symptoms were measured. In addition, there is considerable uncertainty around the reference standard, with some studies providing little detail on the RT‐PCR tests that they used or lack of clarity on blinding.

Participant flow was unclear in four studies (Yan 2020a; Yang 2020d; Zhao 2020a; Zhu 2020b), either because the timing of recording signs and symptoms and conduct of the reference standard was unclear, or because some tests received a second or third reference standard at unclear time points during hospital admission.

We rated applicability for participant selection as high risk when there was a risk of selection bias or studies did not describe selection. As for the applicability of the index tests and reference standard, we always scored this as low risk except for Chen X 2020, because blinding of the index tests was unclear, and Yang 2020d, because blinding and sample of the reference standard were unclear.

Findings

The main characteristics of all included studies are listed in Table 3. There were four studies in hospital inpatients (Ai 2020a; Chen X 2020; Yang 2020d; Zhao 2020a), seven studies in hospital outpatients (Cheng 2020a; Liang 2020; Nobel 2020; Peng 2020a; Song 2020b; Sun 2020a; Yan 2020a), and four studies in emergency departments (Feng 2020a; Tolia 2020; Wee 2020; Zhu 2020b). The setting was not specified in one study (Rentsch 2020); in the 'Summary of findings' table, we classified this study setting as being hospital outpatient under the assumption that at that time in the pandemic (February 2020 to March 2020) tests were not commonly available outside hospital clinics. There were no studies conducted in community primary care services.

Seven studies assessed the accuracy of signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of COVID‐19 pneumonia (Ai 2020a; Chen X 2020; Cheng 2020a; Feng 2020a; Liang 2020; Yang 2020d; Zhao 2020a); the remaining studies had COVID‐19 disease as the target condition, with no further description of the severity, meaning some patients could have suffered from mild or moderate COVID‐19 disease and others from COVID‐19 pneumonia. The distinction between these two target conditions was not always very clear, and a degree of overlap is to be assumed. All studies used RT‐PCR testing as the reference standard, with some variation in the samples that were used.

In all, 7706 patients were included, the median number of participants was 134. Prevalence of infection varied from 5% to 38% with a median of 17%. There were no studies in children or elderly populations, except for Rentsch 2020, which included a cohort of a median age of 65.7 years old from the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System database.

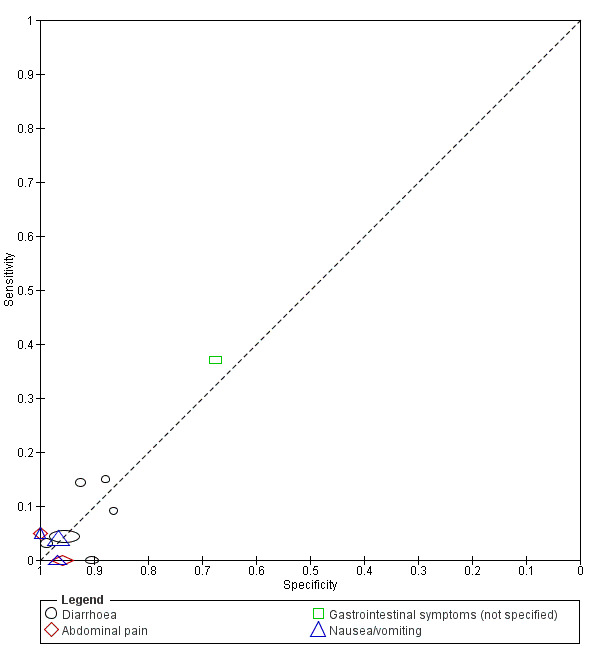

We found data on 27 signs and symptoms, which fall into four different categories: systemic, respiratory, gastrointestinal and cardiovascular signs and symptoms. There were no analyses for combinations of tests, only for individual signs and symptoms. The results are summarised in Table 3. Results for the cross‐sectional studies are presented in forest plots (Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6; Figure 7), and are plotted in ROC (receiver operating characteristic) space (Figure 8; Figure 9; Figure 10; Figure 11), results for the other studies are only listed in forest plots (Figure 12; Figure 13; Figure 14; Figure 15).

4.

Forest plot of respiratory signs and symptoms (cross‐sectional studies)

5.

Forest plot of systemic signs and symptoms (cross‐sectional studies)

6.

Forest plot of gastrointestinal signs and symptoms (cross‐sectional studies)

7.

Forest plot of cardiovascular signs and symptoms (cross‐sectional studies)

8.

Summary ROC plot of respiratory signs and symptoms (cross‐sectional studies)

9.

Summary ROC plot of systemic signs and symptoms (cross‐sectional studies)

10.

Summary ROC Plot of gastrointestinal signs and symptoms (cross‐sectional studies)

11.

Summary ROC plot of cardiovascular signs and symptoms (cross‐sectional studies)

12.

Forest plot of tests: 27 cough (non‐cross‐sectional study), 28 sore throat (non‐cross‐sectional study), 29 rhinorrhoea (non‐cross‐sectional study), 30 nasal obstruction (non‐cross‐sectional study), 34 dyspnoea (non‐cross‐sectional study), 31 loss of sense of smell (non‐cross‐sectional study), 32 loss of taste (non‐cross‐sectional study), 33 positive auscultation findings (non‐cross‐sectional study)

13.

Forest plot of tests: 37 fatigue (non‐cross‐sectional study), 36 fever (non‐cross‐sectional study), 39 headache (non‐cross‐sectional study), 38 myalgia or arthralgia (non‐cross‐sectional study)

14.

Forest plot of tests: 40 diarrhoea (non‐cross‐sectional study), 41 nausea/vomiting (non‐cross‐sectional study), 42 gastrointestinal symptoms, not specified (non‐cross‐sectional study)

15.

Forest plot of 35 chest tightness (non‐cross‐sectional study)

Overall, diagnostic accuracy of individual signs and symptoms is low, especially sensitivity. In addition, results were highly variable across studies, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

Signs and symptoms for which sensitivity was reported above 50% in at least one cross‐sectional study are the following.

Cough: sensitivity between 43% and 71%, specificity between 14% and 54%

Sore throat: sensitivity between 5% and 71%, specificity between 55% and 80%

Fever: sensitivity between 7% and 91%, specificity between 16% and 94%

Myalgia or arthralgia: sensitivity between 19% and 86%, specificity between 45% and 91%

Fatigue: sensitivity between 10% and 57%, specificity between 60% and 94%

Headache: sensitivity between 3% and 71%, specificity between 78% and 98%

For fever, six of nine studies report a sensitivity of at least 80%, which is unsurprising considering fever was a key feature of COVID‐19 that was used in selecting patients for further testing. As a result, most participants in these studies would have fever, both cases and non‐cases. The same applies to cough, which was also listed as one of the main criteria for SARS‐CoV‐2 testing and may have contributed to inflated sensitivity estimates.

Specificity of at least 90% was achieved for 19 signs and symptoms. In only four signs and symptoms did this go along with sensitivity of at least 50% which would correspond to a positive likelihood ratio of at least 5, a commonly used arbitrary definition of a red flag. Using this definition, fever, myalgia or arthralgia, fatigue, or headache are to be considered red flags.

Strikingly, most of the respiratory symptoms such as cough, sore throat and sputum production are below the diagonal in ROC space (Figure 8). The diagonal line in ROC space is where sensitivity equals 1‐specificity, meaning a test that is on the diagonal line has a positive likelihood ratio of 1 and is therefore not diagnostic because disease probability is left unchanged after conducting the test. Tests that lie below the diagonal line have a positive likelihood ratio that is smaller than 1, meaning the probability of COVID‐19 disease decreases when this test is positive. For example, in Sun 2020a, pretest probability of COVID‐19 is 6.9%; probability decreases to 6.4% when the patient has a cough and increases to 8.0% when the patient does not have a cough. We hypothesise on the reason for this counterintuitive finding in the discussion section. In contrast to respiratory features, systemic features are mostly above the diagonal line (Figure 9), suggesting that they do increase the probability of COVID‐19 when present. Gastrointestinal symptoms and cardiovascular features are clustered in the bottom left corner or on the diagonal line suggesting that they have very little diagnostic value (Figure 10; Figure 11).

To further illustrate the systemic features' ability to either rule in or rule out COVID‐19 disease or COVID‐19 pneumonia, we constructed dumbbell plots showing pre‐ and post‐test probabilities for each feature in each study (Figure 16). For each test, we have plotted the pre‐test probability, which is the prevalence of COVID‐19 disease (blue dot). Probability then changes depending on a positive test result (red dot marked +) or a negative test result (green dot marked ‐). The plot shows that fever, for example, increases the probability of COVID‐19 in two studies (Ai 2020a; Rentsch 2020), makes little to no difference in five studies (Feng 2020; Liang 2020; Peng 2020; Song 2020; Zhu 2020), and decreases the probability of COVID‐19 in two studies (Cheng 2020a; Tolia 2020).

16.

Dumbbell plot: this plot shows how disease probability changes after a positive test result (red dot with plus sign) or after a negative test (green dot with minus sign). Pre‐test probability or prevalence is the blue dot

Discussion

Summary of main results

Individual signs and symptoms appear to have very poor diagnostic properties for COVID‐19, although this has to be interpreted in the presence of a limited number of studies, heterogeneity between the studies precluding any firm conclusions and in a context of selection bias. Most features had very low sensitivity, while specificity was moderate to high.

We have identified four possible red flags, that is, symptoms that increased the probability of COVID‐19 when present because of a positive likelihood ratio of at least 5 in at least one study: fever, myalgia or arthralgia, fatigue, and headache. When we apply the results of sensitivity and specificity of these systemic features to disease probabilities, we assess their value to rule in and rule out disease as shown in the dumbbell plots (Figure 16). These clearly show the limited effect on disease probability from these signs and symptoms. Importantly, we did not find any studies investigating the diagnostic accuracy of combinations of signs and symptoms. There were also no studies from community primary care settings.

Some of our findings are counterintuitive, for example that the majority of the studies that investigated cough found that cough decreases the probability of COVID‐19 despite the fact that it is part of the case definition of COVID‐19 in most countries. This is also the case for fever in two studies and myalgia in one study ‐ even though these features were also red flags in at least one other study. We believe this may be caused by selection bias. Selection bias is present when selective and non‐random inclusion and exclusion of participants apply and the resulting association between exposure and outcome (here the accuracy of the test) differs in the selected study population compared to the eligible study population, and it has been shown that this may decrease estimates of diagnostic accuracy (Rutjes 2006). For the diagnosis of COVID‐19, rapidly and constantly changing, and widely variable test criteria have influenced who was referred for testing and who was not. Inclusion in the study of only a selective fraction of eligible patients can give a biased estimate of the real accuracy of the index test when measured against the reference standard and real disease status. Griffith 2020 reported on the problematic presence of collider stratification bias in the published studies on COVID‐19. Appropriate sampling strategies need to be applied to avoid conclusions of spurious relationships, more specifically in our case, the biased accuracy estimates of signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of COVID‐19 disease. Selection of patients based on the presence of specific pre‐set symptoms, such as fever and cough, lead to biased associations between these symptoms and disease, and sensitivity and specificity estimates that differ from their true values. The example of collider bias for cough is illustrated in Figure 17. Grouping studies by diagnostic criteria for selection might clarify this issue, but studies do not clearly describe them, with study authors referring to the guidelines in general that were applicable at the time.

17.

Directed acyclic graph on cough

Another form of selection bias is spectrum bias, where the patients included in the studies do not reflect the patient spectrum to which the index test will be applied. The inclusion of hospitalised patients can lead to such a bias, when in these patients both the distribution of signs and symptoms differ and assessment with the reference standard is differential. In addition, the distribution and severity of alternative diagnoses may be different in hospitalised populations than in patients presenting to ambulatory care settings.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

Strengths of our review are the systematic and broad search performed to include all possible studies, including those prior to peer‐review, to gather the largest number of studies available at this point. Exclusion of cases‐only studies, the largest number of the published cohorts of patients with COVID‐19, limits the available data but also improves the quality of the evidence and the possibility to present both sensitivity and specificity (cases only cannot provide both accuracy measures). Because this is a living systematic review, future updates may offer the possibility to do a meta‐analysis, which was not possible at this stage. In addition, further insights into this novel disease may lead to new evidence on signs and symptoms that are more diagnostic, which we will incorporate in future updates.

The lack of data on combinations of signs and symptoms is an important evidence gap. Consequently, there is no evidence on syndromic presentation and the value of composite signs and symptoms on the diagnostic accuracy measures. In addition, subgroup analyses by the pre‐defined variables were not feasible due to lack of reporting.

We need to assess multiple variables for their possible confounding effect on the summary estimates. Possible confounders include the presence of other respiratory pathogens (seasonality), the phase of the epidemic, exposure to high versus low prevalence setting, high or low exposure risk, comorbidity of the participants, or time since infection. Seasonality may influence specificity, because alternative diagnoses such as influenza or other respiratory viruses are more prevalent in winter, leading to more non‐COVID‐19 patients displaying symptoms such as cough or fever, decreasing specificity. In this version of the review, all studies were conducted in Winter or early Spring, suggesting this may still have been at play. However, social distancing policies have shortened this year's influenza season in several countries (www.who.int/influenza/surveillance_monitoring/updates/en/), which may have led to higher specificity for signs and symptoms than what we may expect in the next influenza season. In future updates of the review, we will explore seasonality effects if data allow. As for time since onset, given that the moment of infection is more likely than not an unrecognisable and unmeasurable variable, time since onset of symptoms can be used as a proxy. Reporting of studies, with presentation of the 2x2 table stratified by time since onset of disease, is informative and might have the potential to increase accuracy of the signs and symptoms and their diagnostic differential potential.

Applicability of findings to the review question

The high risk of selection bias, with many studies including patients who had already been admitted to hospital or who presented to hospital settings with the intent to hospitalise, leads to findings that are less applicable to people presenting in primary care, who on average experience a shorter illness duration, less severe symptoms and have a lower probability of the target condition.

Our search did not find any articles providing data on children. Children have been underrepresented in the studies on diagnosing SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Their absence seems related to the general mild presentation of the disease in the paediatric population, and the even more frequent asymptomatic course of COVID‐19 in children. The full scope of disease presentation in children is therefore not known. It is important to identify signs and symptoms that can be used to clinically assess children with suspected COVID‐19, especially because aspecific presentations and fever without a source are already common in this age group, and acute infection in children is a common cause for families to self‐isolate or get tested. Misclassification of children, where children will be asked to remain in quarantine when they present with predefined, but not yet evidence‐based symptoms needs to be avoided to decrease the possible damage done to children's health and education. Having separate data for neonates, young infants, toddlers, school‐aged children and adolescents is therefore of value.

Another important patient group is older adults. They are most at risk of an adverse outcome of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, including an increased risk of requiring intensive care support and and increased risk of mortality. In this version of the review, only one study focused on adults aged 55 to 75 years. All other studies included adults of all ages and did not present results separately for older age groups. The lack of a solid evidence base for the diagnosis of COVID‐19 in older adults adds to the difficulty in diagnosing serious infections in this age group, as other serious infections such as bacterial pneumonia or urinary sepsis also tend to lead to aspecific presentations.

The association of a single sign or symptom with COVID‐19 is highly uncertain, and we do not have data on combinations of signs and symptoms. Additionally, potentially more diagnostic symptoms such as loss of sense of smell have not yet been studied widely and remain to be assessed in well designed studies. Moreover, the nature of the signs and symptoms that are used to guide self‐isolation decisions are such that people may end up being quarantined on a regular basis, leading to missed days at school or work, isolation and anxiety.

In future updates of this review, we intend to organise findings by age group, settings (in particular primary care settings versus hospital settings), and target condition, when evidence allows.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results were highly variable across studies, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Selection bias further hinders interpretability. Until results of further studies become available, broad investigation of patients with suspected SARS‐Cov‐2 infection remains necessary. Neither absence nor presence of the individual signs and symptoms included in this review are accurate enough to rule in or rule out disease.

Implications for research.

Our review reflects the need for improved study methodology in COVID‐19 diagnostic accuracy research: appropriate patient sampling strategies; prospective one‐gate design; and investigating the presence or absence of clinical signs and symptoms in all suspected patients. In addition, we urgently need studies in community primary care settings, and studies investigating combinations of signs and symptoms. Evidence on signs and symptoms that are used for testing or referral decisions, such as loss of sense of smell, heart rate, breathing rate and oxygen saturation, should be included in future studies using clearly stated definitions and cut‐offs. In order to inform self‐isolation policies, studies in community settings, where prevalence is lower than in the included studies, will be needed to better determine the balance of risks arising from false positives and false negatives.

We also need improved reporting with studies clearly describing how they assessed signs and symptoms, when and by whom, and providing clearer definitions of what constitutes an abnormal sign or symptom. Studies also need to report reference standards more clearly.

In addition, more data on specific patient groups with comorbidities at higher risk of complications or severe disease are needed, especially older adults, as missing COVID‐19 disease may have more serious consequences in these patients. We also need to have more studies in children.

We would like to recommend authors to adhere to the STARD guidelines when reporting new studies on this topic (Bossuyt 2015).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 July 2020 | Amended | Resolution of two figures improved |

History

Review first published: Issue 7, 2020

Acknowledgements

Members of the Cochrane COVID‐19 Diagnostic Test Accuracy Review Group include:

the project team (Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, Davenport C, Leeflang MMG, Spijker R, Hooft L, Van den Bruel A, McInnes MDF, Emperador D, Dittrich S);

-

the systematic review teams for each review:

Molecular, antigen, and antibody tests (Adriano A, Beese S, Dretzke J, Ferrante di Ruffano L, Harris I, Price M, Taylor‐Phillips S)

Signs and symptoms (Stuyf T, Domen J, Horn S)

Routine laboratory markers (Yang B, Langendam M, Ochodo E, Guleid F, Holtman G, Verbakel J, Wang J, Stegeman I)

Imaging tests (Salameh JP, McGrath TA, van der Pol CB, Frank RA, Prager R, Hare SS, Dennie C, Jenniskens K, Korevaar DA, Cohen JF, van de Wijgert J, Damen JAAG, Wang J)

the wider team of systematic reviewers from University of Birmingham, UK who assisted with title and abstract screening across the entire suite of reviews for the diagnosis of COVID‐19 (Agarwal R, Baldwin S, Berhane S, Herd C, Kristunas C, Quinn L, Scholefield B).

We thank Dr Jane Cunningham (World Health Organization) for participation in technical discussions and comments on the manuscript.

We would like to acknowledge Joanne Merckx for her contribution to the data extraction of nine papers in the initial stages of this review. Due to conflict of interest, a decision was taken to have a systematic reviewer, Nicholas Henschke, independently check all data extracted by her before publication.

The editorial process for this review was managed by Cochrane's EMD Editorial Service in collaboration with Cochrane Infectious Diseases. We thank Helen Wakeford, Anne‐Marie Stephani and Deirdre Walshe for their comments and editorial management. We thank Robin Featherstone for comments on the search and Mike Brown and Paul Garner for sign‐off comments. We thank Denise Mitchell for her efforts in copy‐editing this review.

Thank you also to peer referees Trish Greenhalgh, Robert Walton, Chris Cates and Lynda Ware, consumer referee Jenny Negus, and methodological referees Gianni Virgili and Marta Roqué, for their insights.

The editorial base of Cochrane Infectious Diseases is funded by UK aid from the UK Government for the benefit of low‐ and middle‐income countries (project number 300342‐104). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government’s official policies.

Jonathan Deeks is a UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator Emeritus. Yemisi Takwoingi is supported by a NIHR Postdoctoral Fellowship. Jonathan Deeks, Jacqueline Dinnes, Yemisi Takwoingi, Clare Davenport and Malcolm Price are supported by the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre. This paper presents independent research supported by the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Birmingham. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Appendices

Appendix 1. World Health Organization case definitions

Severe pneumonia

Adolescent or adult: fever or suspected respiratory infection, plus one of the following: respiratory rate > 30 breaths/minute; severe respiratory distress; or oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤ 93% on room air. Child with cough or difficulty in breathing, plus at least one of the following: central cyanosis or SpO2 < 90%; severe respiratory distress (for example, grunting, very severe chest indrawing); signs of pneumonia with a general danger sign: inability to breastfeed or drink, lethargy or unconsciousness, or convulsions.

Other signs of pneumonia may be present: chest indrawing, fast breathing (in breaths/minute): aged < 2 months: ≥ 60; aged 2 to 11 months: ≥ 50; aged 1 to 5 years: ≥ 40. While the diagnosis is made on clinical grounds; chest imaging may identify or exclude some pulmonary complications.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Onset within one week of a known clinical insult or new or worsening respiratory symptoms.

Chest imaging (that is, X‐ray, computed tomography scan, or lung ultrasound): bilateral opacities, not fully explained by volume overload, lobar or lung collapse, or nodules.

Origin of pulmonary infiltrates: respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload. Need objective assessment (for example, echocardiography) to exclude hydrostatic cause of infiltrates/oedema if no risk factor present.

Oxygenation impairment in adults:

mild acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): 200 mmHg < ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure/fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ≤ 300 mmHg (with positive end‐expiratory pressure (PEEP) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ≥ 5 cmH2O, or non‐ventilated);

moderate ARDS: 100 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg (with PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O, or non‐ventilated);

severe ARDS: PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 100 mmHg (with PEEP ≥ 5 cmH2O, or non‐ventilated);