Abstract

Purpose

The objective is to present a case of well-leg compartment syndrome in the Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position.

Results

The case of a 32-year-old male, obese (105 Kg) and a former smoker is presented. The patient was positioned in the Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position, with lower limbs bandaged, to perform a right percutaneous nephrolithotomy. In the immediate postoperative period, significant pain was reported in the left lower limb. The limb appeared oedematous and cyanotic, although pedis pulses were preserved. Doppler ultrasound ruled out venous thrombosis. Suspecting compartment syndrome, the patient underwent a complete decompression fasciotomy of the four left leg compartments. After the surgery, values of creatine phosphokinase reached 80.000 UI/L and serum creatinine levels were 1.53 mg/dL. The patient was taken to the intensive care unit. Six months after the episode, the patient still needs rehabilitation care. The compartment syndrome is a rare complication in lithotomy position, but never described in the Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position before, with the lower limbs in moderate flexion, and with the ipsilateral lower limb in a slightly inferior position with respect to the other. It may lead to skin necrosis, permanent neuromuscular dysfunction, myoglobinuric renal failure, amputation and even death. Therefore, this complication must be suspected and early decompression of the compartment must be performed. Risk factors include obesity, peripheral vascular disease (advanced age, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes mellitus), height, hypothermia, acidemia, BMI, male sex, combined general-spinal anesthesia, prolonged surgery time, systemic hypotension, ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) class, lack of operative experience, vasoconstricting drugs, important bleeding during the surgery and increased muscle bulk.

Conclusion

Compartment syndrome is a potentially life-threatening complication that may occur in the Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position. It should be suspected in cases with risk factors and compatible clinical symptoms and signs, and treated rapidly to avoid further complications.

Keywords: well-leg compartment syndrome, percutaneous nephrolithotomy, Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position

Introduction

Acute compartment syndrome of the leg occurs following a rise in the pressure inside the muscle compartment.1 A failure of delay in diagnosis may result in adverse outcomes for the patient,2 which can even lead to an admission to an Intensive Care Unit with a renal failure subsidiary of renal replacement therapy or even death. Therefore, it is essential to consider the possibility of this complication in a patient presenting symptoms compatible with compartment syndrome.

It has been described that lithotomy position, in general surgical, urological and orthopaedic patients, is associated with changes in intracompartmental pressure that may eventually develop a compartment syndrome, especially in prolonged surgeries.3–6 A significant decrease in deep muscle mixed tissue oxygen saturation of calf muscles has been observed, due to the combined effect of perfusion-related factors, such as hydrostatic forces, blood and intraabdominal pressure, which lead to tissue underperfusion.7,8

However, this type of compartment syndrome is not part of the common complications of percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL). Its development in a modified Valdivia position, in which the lower limbs not only present a more moderate flexion than in other endourological procedures but also have the particularity of placing one of the lower extremities in a position slightly lower than the other, has never been reported.9

The factors associated with the development of this complication have been described in some articles: obesity, advanced age, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, combined general-spinal anesthesia, prolonged surgery time, systemic hypotension…10 In addition, strategies have also been developed to prevent the occurrence of this complication, including limitation of the patients’ position, optimal medical management of comorbidities before surgery, or even the use of checklists.8

The objective of the study is to present the case of a well-leg compartment syndrome in the Galdakao position; and to analyze the risk factors, pathophysiology, treatment and prognosis of this complication.

Case Report

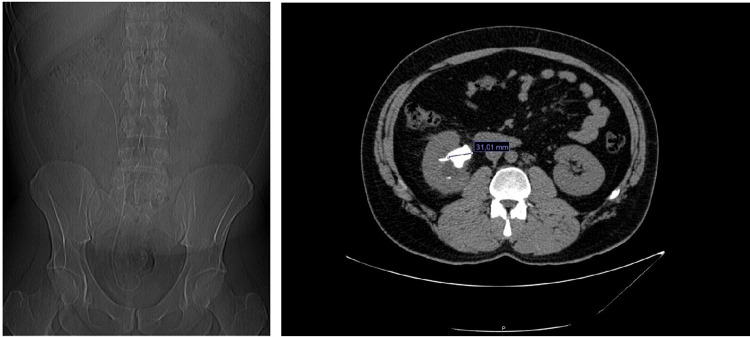

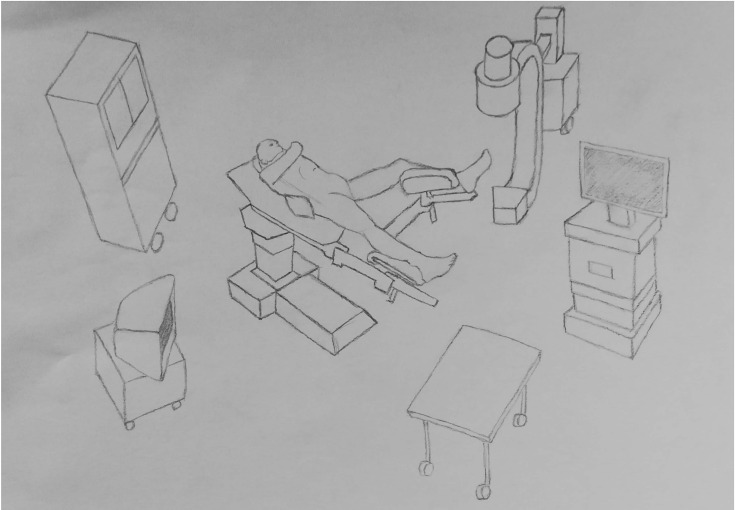

We present the case of a 32-year-old male, obese (105 Kg) and a former smoker. He had undergone a right double J stent due to an obstructive 3.5 cm staghorn lithiasis in the renal pelvis, 2.5 months ago (Figure 1). The patient was positioned in the Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position (Figure 2) to perform a right PCNL. The lower extremities were bandaged to prevent venous thrombosis, as established by the hospital protocol. First, an endoscopic cystolithectomy needed to be performed, since the double J stent was calcified distally. Second, the double J stent was removed and retrograde pyelography was performed. The upper urinary tract was accessed through an X-ray and ultrasound guided puncture of the lower calyx. After dilation, it was impossible to access the stone with the nephroscope since the Amplatz did not reach the lumen, due to a long stone-skin distance. With many difficulties and the use of flexible devices through the lumbar access, Holmium laser and Dormia catheters, it was eventually possible to eliminate the lithiasis completely. The entire procedure lasted 4.5 hrs.

Figure 1.

CT scan showing the right staghorn lithiasis.

Figure 2.

The Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position.

The patient was taken to the recovery room. In the immediate postoperative period, despite analgesic infusion, significant pain was reported in the left lower limb. The limb appeared oedematous and cyanotic, although the pedis pulses were preserved. Doppler ultrasound ruled out venous thrombosis. Suspecting compartment syndrome, the patient was taken back to the operating room.

Findings were general inflammation of the left leg and dorsal ankle flexion and finger mobility deficit. Muscle mass from the deep posteromedial compartment and the deep anterolateral compartment showed evidence of ischemia. Pale pink oedema and absence of contractility upon stimulation with an electric scalpel were observed. The muscle mass of both superficial compartments appeared with the correct tonality and contractility.

A complete decompression fasciotomy of the four compartments of the left leg was performed with a double approach. The edges were approximated with vessel-loop.

After surgery, creatine phosphokinase values reached 80,000 IU/L and serum creatinine levels were 1.53 mg/dL, with a glomerular filtration rate of 53.01 mL/min. The patient was taken to the Intensive Care Unit.

Through intensive therapy with serum and diuretics, a progressive and complete recovery of kidney function was achieved. Rhabdomyolysis was also controlled, observing a decrease in its markers during admission to the unit. Twenty days after fasciotomy, the skin was finally closed with Prolene.

There were no signs of systemic infection during admission. The patient remained hemodynamically stable at all times, maintaining Mean Arterial Pressure over 65 mmHg. The Rehabilitation Service was requested to improve leg recovery and normal mobility.

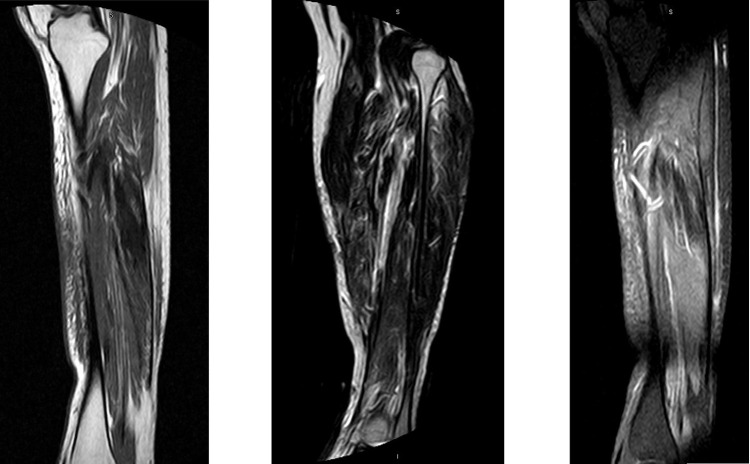

Six months after the episode, the patient still needed rehabilitation care. The magnetic resonance (Figure 3) showed the presence of a certain degree of discrete muscular oedema in a trajectory of approximately 18 cm, which affects the soleus muscles, with a chronic appearance. There is a certain degree of fat infiltration mainly in the proximal third of the muscle mass. Likewise, an apparent degree of scarring and/or fibrosis is also detected in the muscle. The fascia signal is preserved.

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance imaging showing sequelae at 6 months.

Review of the Literature

The Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position has been widely used for PCNL since it was described by Ibarluzea et al in 2007.11 It allows the treatment of both renal and ureteral stones simultaneously to remove encrusted stents and to easily place double J stents and percutaneous nephrostomies. It provides a position in which the patient does not need to be relocated during the surgery, shortening the operation time, and allows two surgeons to be operating simultaneously.

Well-leg compartment syndrome after prolonged procedures performed in the lithotomy or extreme Trendelenburg positions is a rare but potentially devastating complication.12 It is also believed to have been underreported in the literature, due to failed diagnosis or misdiagnosis as deep vein thrombosis or neuropraxia.13,14 Overall estimated frequency in the lithotomy position is 1:3500.7 Nevertheless, there are several references of compartment syndrome associated with lithotomy position in colorectal and gynecological surgeries.15 They have also been described in the field of urology,13 bilaterally on some occasions.16–18 Most of the cases described in urology have been related to the performance of a radical prostatectomy, either laparoscopic or robotic.2,19

In this case, the surgery corresponded to a right PCNL. The patient was placed in a slightly different position from the classic lithotomy, with the lower limbs in moderate flexion, and with the ipsilateral lower limb in a slightly inferior position with respect to the other (Figure 2). To our knowledge, the development of well-leg compartment syndrome has never been reported before in this position.

There are four main compartments in the lower limb: anterior, lateral, superficial posterior and deep posterior. Muscles and neurovascular structures are bordered by strong, inelastic fascial layers and bone. The superficial and deep branches of the peroneal nerve, and the tibial and sural nerves course through these compartments. The sheath limits the extent to which a compartment can be accommodated.1 The anterior compartment is most commonly involved.13 The compartmental pressures rise as soon as legs are placed in the lithotomy position.7 The height of elevation of the legs above the level of the heart is crucial.7,8 In our case, in the Galdakao position, the contralateral leg is placed in a slightly lower height than in the lithotomy position, despite which the complication occurred.

Studies have shown that, in lithotomy position, support behind the calf or the knee increased intracompartment pressure to 16.5 (SD 3.4) mmHg vs 10.7 (SD 5.8) mmHg.5 The result of increased tissue pressure within a closed osteofascial compartment compromises the circulation. Compression of the calf contributes to local ischaemia either directly, occluding the arterial blood flow or indirectly, obstructing the venous drainage. Further compression may come from the weight of the limb itself and the use of other devices, such as cushions and braces, or the compression caused by the operating personnel.7 The use of compressive leg wraps has been associated with well-leg compartment syndrome in some studies,3 while in others a reduction in intracompartment pressure of the lower leg was observed with the use of external intermittent compression.5

Tissue perfusion is proportional to the difference between capillary perfusion pressure and the interstitial fluid pressure. When the latter exceeds the former, a capillary collapse occurs with consequent muscular and nervous ischaemia.20

The initial ischaemia disrupts the integrity of the vascular endothelium and its ability to maintain the barrier to solute and serum movement, setting in motion a self-perpetuating cycle of ischaemia and tissue oedema. The compartment pressure may increase further when returning the patient to supine position and produce a reperfusion injury.1,7 Moreover, once reperfusion occurs, large amounts of toxic intracellular contents are released into the bloodstream (markers of rhabdomyolysis).8 Serum creatine phosphokinase has been seen to increase significantly after surgery, with a peak at 18 hrs.2

Risk factors associated with the development of compartment syndrome reported in the literature are included in Table 1.7,8,10,13–15,21,22 Our patient, although young, was a former smoker. He was obese (105 Kg) and also had increased muscle bulk. He had undergone lower limbs bandaging to prevent venous thrombosis. The surgery was prolonged (lasted 4.5 hrs.) What is striking is that the position of the involved limb, the left one, was not in such an elevated position as in the majority of cases reported in the literature. Moreover, the calf was only slightly higher than the heart.

Table 1.

Risk Factors Associated with the Development of Compartment Syndrome Reported in the Literature

| Related to the patient | Obesity |

| Advanced age | |

| Hypertension | |

| Hyperlipidemia | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | |

| Height | |

| BMI | |

| Male sex | |

| ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) class | |

| Increased muscle bulk | |

| Related to the surgery | Prolonged surgery time |

| Systemic hypotension | |

| Acidemia | |

| Lack of operative experience | |

| Combined general-spinal anesthesia | |

| Hypothermia | |

| The use of vasoconstricting drugs | |

| Important bleeding during the surgery | |

| Wrapping elevated legs |

As for preventive measures, one of them would be to limit the time the patient is in the lithotomy, Trendelenburg or Galdakao position, reserving it only for when necessary.23 It is advisable to avoid wrapping elevated legs. The use of intermittent compression remains controversial, as it decreases the incidence of deep vein thrombosis significantly but it may also increase the risk of compartment syndrome. It is advisable to avoid full passive plantar flexion.7 A split leg table may have theoretical advantages over stirrups.8 It might also be beneficial to place the patient’s calves just below the level of the right atrium, minimizing the degree of ankle elevation.13,21

Obese patients may be encouraged to lose weight prior to the procedure. Also, optimal medical management of comorbidities such as diabetes or peripheral vascular disease is vital.24 Checklists may aid injury prevention by directing attention towards operation-related risk factors.8

The intensity of the epidural block should be appropriate to the anticipated intensity of the pain. The patient should be well hydrated and blood pressure maintained in the normal range.7 It has been postulated that the measurement of intraoperative serum creatine phosphokinase in patients undergoing prolonged procedures during ventilation and sedation might represent an early marker for the diagnosis of compartment syndrome.13

In patients at high risk, the compartmental pressure may be monitored intraoperatively. It has been suggested that monitoring may detect compartment syndrome prior to the onset of clinical signs, in addition to reducing the time to fasciotomy and development of subsequent sequelae.20 In patients with marginal elevations, the use of mannitol induces osmotic diuresis and acts as a free radical scavenger. Another measure for high-risk patients is to monitor the urinary pH in order to prevent precipitation of myoglobin and urate, through an infusion of sodium bicarbonate or acetazolamide.7

There must be an acute level of suspicion regarding the possibility of this problem after lengthy surgeries, as early diagnosis and treatment by four-compartment fasciotomy are the only way to prevent irreversible damage.15 The development of this syndrome should be considered in a patient with a pain out of proportion (often described as burning, deep in nature and reproduced by passive stretching of the muscles of that compartment), paraesthesia, paresis of muscles, pink skin, presence of pulse and increased serum creatinine kinase activity. The earliest signs are subtle and most often neurological because the tissues most sensitive to hypoxia are nonmyelinated type C sensory fibers.13,20 It should be taken into account that epidural anesthesia may delay the diagnosis due to a masking effect.13 In our case, the patient underwent general anesthesia, which theoretically did not influence in the development of the complication.

Definitive diagnosis is assessed by directly measuring compartmental pressure. A value of 20–30 mmHg is thought to indicate the need for a fasciotomy, but that may vary depending on the clinical setting; it also depends on the perfusion pressure.20 There are also some non-invasive imaging techniques for determining intracompartment pressure, including near-infrared spectroscopy, ultrasonic devices and laser Doppler flowmetry.1 The limb may be capable of being saved up to 10–12 hrs after the complication sets in. Differential diagnoses include venous thrombosis and arterial or peripheral nerve injury.7 Diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis is the presence of myoglobinuria in the absence of urinary erythrocytes and increased serum creatine phosphokinase activity. Other markers are lactate dehydrogenase, aspartate and alanine aminotransferase, phosphate and potassium.7

In our case, Doppler ultrasound ruled out venous thrombosis. Compartment pressure measurement was not performed as the clinical signs and symptoms seemed quite obvious, once venous thrombosis was discarded. In our opinion, if the diagnosis is not clear, compartment pressure must be assessed.

Regarding the treatment, early decompression of the compartment must be performed by an orthopedic surgeon, to avoid the self-perpetuating cycle of ischaemia and oedema. In rhabdomyolysis, myoglobinuric renal failure develops, followed by multisystemic organ failure and possible death. Both surgical and medical treatments are shown in Table 2.1,7,13,20

Table 2.

Surgical and Medical Treatment of Well-Leg Compartment Syndrome

| Surgical treatment | If necessary, four compartments opening Long incisions (20–25 cm) along the length of the leg Complete release of all involved compartments Preservation of vital structures Necrotic tissue removal Avoidance of superficial peroneal nerve damage In muscles under tension: skin left open Use of moist dressings Skin incisions closing after a few days (for repeat irrigation and debridement) |

| Medical treatment | Adequate analgesia Early and aggressive fluid replacement Central venous monitoring Transferring to high dependency unit/intensive care therapy unit Adequately hydration (target urinary output of at least 0.5 mL/kg.) Use of mannitol (renal vasodilator effect, expands intravascular volume and decreases oxygen radicals) Urinary ph maintained as neutral as possible (avoidance urate and myoglobin precipitation): sodium bicarbonate or acetazolamide |

The damage is thought to be reversible if the ischemic time is < 2 hrs. When cell death occurs it results in permanent disability (in this order: sensitive nerves, motor nerves, muscle and bone).7 In our patient, it took 3 hrs to realize he was suffering from a compartment syndrome, after ruling out venous thrombosis with a Doppler ultrasound.

Although the majority of positioning injuries resolve in 1 month, they may persist beyond 6 months.22 In our case, the patient’s MRI still showed signs of damage 6 months after the surgery, despite the fact that he was attending rehabilitation care.

Prognosis depends on various factors: injury severity, duration of ischaemia, pre-injury status and comorbidities and most importantly time to fasciotomy.20

A delay in decompression may lead to 20% of the patients requiring amputation. In the long term, reported complication rates of early and late fasciotomies are 4.5% and 54%, respectively. Pain and altered sensation around the fasciotomy wound occur in 10% and 77%, respectively.7 Beyond 12 hrs, a permanent neuromuscular dysfunction from muscle necrosis and nerve ischaemia is reported.1 A Volkmann contracture may also occur. Also, delayed fasciotomy is associated with loss of the limb as it exposes necrotic muscle to infection.7 Where the diagnosis has been missed or delayed supportive renal treatment should be considered and surgery delayed until the morbidity has been removed and reconstruction can be planned.20

Fasciotomy complications are shown in Table 3.7,13,20

Table 3.

Fasciotomy Complications

| Complication | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Dry scaly skin | 40% |

| Discolored wounds | 30% |

| Tethered scars | 26% |

| Muscle herniation | 13% |

| Pruritus | 33% |

| Swollen limbs | 25% |

| Recurrent ulceration | 13% |

| Tethered tendons | 7% |

| Appearance of scars causing discomfort | 23% |

| Chronic venous insufficiency | – |

The loss of 1 or 2 compartments can be tolerated. Ambulation may return to normal with aggressive physiotherapy, or the use of splints or ankle-foot orthoses. If more compartments are lost, amputation may be required. Nerve injuries can lead to foot drop, ankle equines, equinovarus, cavus foot and claw or hammer toes, which lead to impairment of gait, difficulty with shoe wear and pressure areas from the deformity.13

Well-leg compartment syndrome may lead to permanent disability and, therefore, has considerable medico-legal implications. This may apply to other rare and life-threatening syndromes during PCNL, such as acute abdominal syndrome.25

Therefore, in our opinion, well-leg compartment syndrome is a rare, but potentially devastating complication that may occur during the development of a PCNL in the Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position. Thus, in prolonged surgeries and in patients with risk factors, high levels of awareness of the possibility of this condition are advisable, leading possibly to early treatment.

Conclusions

Compartment syndrome is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication that may also occur in the Galdakao-modified supine Valdivia position in the development of a PCNL. It should be suspected in prolonged surgeries, in patients with previous risk factors and compatible symptoms. It may lead to skin necrosis, permanent neuromuscular dysfunction, myoglobinuric renal failure, amputation and even death. Early diagnosis and treatment by four-compartment fasciotomy is the only way to prevent irreversible damage.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr Graham McKee, who greatly assisted the study.

Abbreviations

SD, standard deviation; PCNL, percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent has been provided by the patient to have the case details and any accompanying images published. It was approved by Ramón y Cajal University Hospital Ethics Committee.

Author Contributions

Drs Laso-García and Arias-Fúnez contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Drs Díaz-Pérez and Lorca-Álvaro. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Drs Burgos-Revilla, Duque Ruiz and Laso-García. Drs Arias-Fúnez, Díaz-Pérez and Lorca-Álvaro critically reviewed the article. All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Mabvuure NT, Malahias M, Hindocha S, Khan W, Juma A. Acute compartment syndrome of the limbs: current concepts and management. Open Orthop J. 2012;6(1):535–543. doi: 10.2174/1874325001206010535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattei A, Di Pierro GB, Rafeld V, Konrad C, Beutler J, Danuser H. Positioning injury, rhabdomyolysis, and serum creatine kinase-concentration course in patients undergoing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy and extended pelvic lymph node dissection. J Endourol. 2013;27(1):45–51. doi: 10.1089/end.2012.0169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen SA, Hurt WG. Compartment syndrome associated with lithotomy position and intermittent compression stockings. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(5):832–833. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01141-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke D, Mullings S, Franklin S, Jones K.Well leg compartment syndrome. Trauma Case Rep.2017;11:5–7. Elsevier Ltd. doi: 10.1016/j.tcr.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfeffer SD, Halliwill JR, Warner MA. Effects of lithotomy position and external compression on lower leg muscle compartment pressure. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(3):632–636. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200109000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill M, Fligelstone L, Keating J, et al. Avoiding, diagnosing and treating well leg compartment syndrome after pelvic surgery. Br J Surg. 2019;106(9):1156–1166. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mumtaz FH, Chew H, Gelister JS. Lower limb compartment syndrome associated with the lithotomy position: concepts and perspectives for the urologist. BJU Int. 2002;90(8):792–799. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.03016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sukhu T, Krupski TL. Patient positioning and prevention of injuries in patients undergoing laparoscopic and robot-assisted urologic procedures. Curr Urol Rep. 2014;15(4):398. doi: 10.1007/s11934-014-0398-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wollin DA, Preminger GM.Percutaneous nephrolithotomy: complications and how to deal with them. Urolithiasis.2018;46:87–97. Springer Verlag. doi: 10.1007/s00240-017-1022-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizuno J, Takahashi T. Male sex, height, weight, and body mass index can increase external pressure to calf region using knee-crutch-type leg holder system in lithotomy position. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:305. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S86934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibarluzea G, Scoffone CM, Cracco CM, et al. Supine Valdivia and modified lithotomy position for simultaneous anterograde and retrograde endourological access. BJU Int. 2007;100(1):233–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06960.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung JH, Ahn KR, Park JH, et al. Lower leg compartment syndrome following prolonged orthopedic surgery in the lithotomy position -A case report-. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;59(Suppl):S49–S52. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2010.59.S.S49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raza A, Byrne D, Townell N. Lower limb (Well Leg) compartment syndrome after urological pelvic surgery. J Urol. 2004;171(1):5–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000098654.13746.c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simms MS, Terry TR. Well leg compartment syndrome after pelvic and perineal surgery in the lithotomy position. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:534–536. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.030965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wassenaar EB, van den Brand JGH, van der Werken C. Compartment syndrome of the lower leg after surgery in the modified lithotomy position: report of seven cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(9):1449–1453. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0688-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin KY, Hemington-Gorse SJ, Darcy CM. Bilateral well leg compartment syndrome associated with lithotomy (Lloyd Davies) position during gastrointestinal surgery: a case report and review of literature. Eplasty. 2009;9:e48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T, Fujie A, Tanikawa H, Funayama A, Fukuda K. Bilateral well leg compartment syndrome localized in the anterior and lateral compartments following urologic surgery in lithotomy position. Case Rep Orthop. 2018;2018:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tison C, Périgaud C, Vrignaud S, Capelli M, Lehur PA. Bilateral compartment syndrome after colorectal surgery in the lithotomy position. Ann Chir. 2002;127(7):535–538. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3944(02)00829-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosevear HM, Lightfoot AJ, Zahs M, Waxman SW, Winfield HN. Lessons learned from a case of calf compartment syndrome after robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2010;24(10):1597–1601. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donaldson J, Haddad B, Khan WS. The pathophysiology, diagnosis and current management of acute compartment syndrome. Open Orthop J. 2014;8(1):185–193. Bentham Science Publishers Ltd. doi: 10.2174/1874325001408010185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romero FR, Pilati R, Kulysz D, Canali FAV, Baggio PV, Brenny Filho T. Combined risk factors leading to well-leg compartment syndrome after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Actas Urol Esp. 2009;33(8):920–924. doi: 10.1016/S0210-4806(09)72883-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills JT, Burris MB, Warburton DJ, Conaway MR, Schenkman NS, Krupski TL. Positioning injuries associated with robotic assisted urological surgery. J Urol. 2013;190(2):580–584. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.3185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Googe B, Lackey AE, Arnold PA, Vick LR. The modified lithotomy: a surgical position for lower extremity wound care procedures in super morbidly obese patients. A case study. Wound Manag Prev. 2019;65(7):30–34. doi: 10.25270/wmp.2019.7.3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takechi K, Kitamura S, Shimizu I, Yorozuya T. Lower limb perfusion during robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy evaluated by near-infrared spectroscopy: an observational prospective study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18(1):114 BioMed Central Ltd. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0567-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao J, Sheng L, Zhang H, Chen R, Sun Z, Qian W. Acute abdominal compartment syndrome as a complication of percutaneous nephrolithotomy: two cases reports and literature review. Urol Case Rep. 2016;8:12–14. Elsevier Inc. doi: 10.1016/j.eucr.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]