Interpersonal violence has plagued our large cities for decades (1,2). As our region and medical system prepared to manage the anticipated influx of critically ill Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients, we sincerely hoped social distancing measures would interrupt this cycle of interpersonal violence.

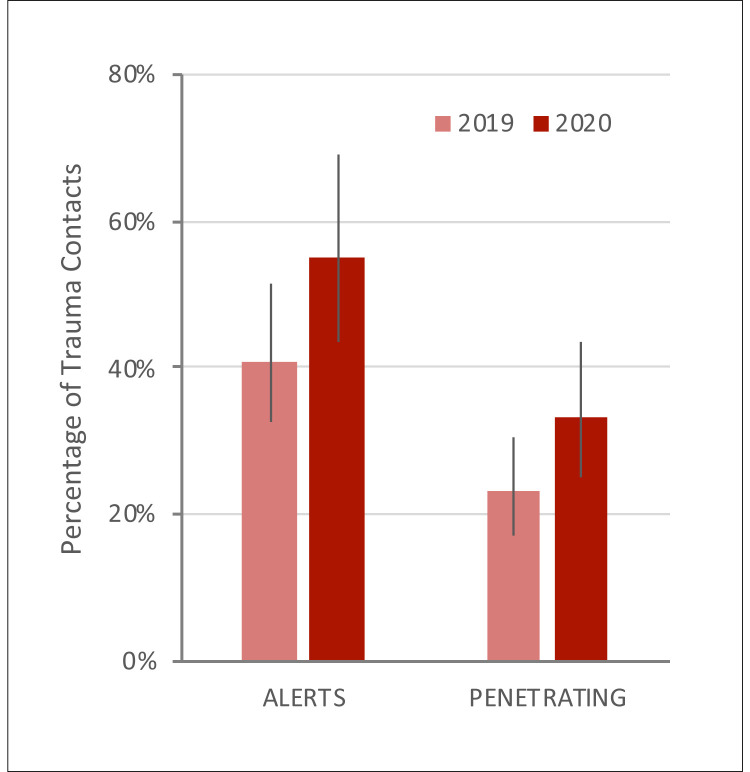

However, in many large metropolitan centers across the country—including Chicago, Dallas, Houston, and Philadelphia—this epidemic of violence, fueled by irresponsible and often criminal use of handguns, has intensified in recent weeks (3). Our center's experience has mirrored this trend. Although blunt injuries have decreased with less vehicular and pedestrian traffic, in the 6 weeks since the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic, our highest-level activations and penetrating injuries have risen sharply in comparison with the same period in 2019 (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Trauma center activity during the current COVID-19 pandemic (March 9, 2020 to April 19, 2020) as compared with the same time period in 2019. Although overall trauma contacts decreased by 16.7% (264 in 2019 vs. 220 in 2020), the proportion of critically injured patients requiring the highest-level activation (ALERTS) increased significantly (41% vs. 55%, p = 0.003), along with the rate of penetrating trauma (23% vs. 33%, p = 0.009). Error bars denote 95% confidence interval. Data obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Trauma Registry.

This observation prompts two questions. First, how do we balance the simultaneous demand for additional high-acuity trauma care while meeting the unprecedented pandemic-fueled demand for those same critical resources? Like most others across the country, our center has cancelled all elective procedures and rapidly re-configured and expanded our inpatient space to meet the pandemic surge. Even with such aggressive measures, at least one metropolitan area with a high concentration of COVID-19 activity significantly curtailed trauma services due to lack of bed availability, creating limited regional access to trauma care, thereby potentially increasing preventable deaths (4). To avoid such a quandary and remain fully open to trauma, we diligently attend to patient throughput in our trauma bay, designate a minimum of two open “crash” trauma critical care beds at all times, and actively arbitrate critical care beds assignments with multidisciplinary input.

Second, how can we remedy this epidemic of violence? In the short term, community interventions and social services focused on acute urban societal stresses must be deployed into violence hot spots. Longer term, funding for gun violence research through private philanthropy and federal agencies including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health must significantly increase to match the burden of disease caused by this epidemic (5,6). Medical journals must commit to disseminate timely and actionable findings from these research activities on gun violence (7). Civic interventions should include training nonviolent conflict resolution focused especially on our youth in schools, religious organizations, and community centers. We must also train, equip, and empower individuals to stop critical bleeding with tourniquets and hemostatic dressings when injuries do occur. Finally, legislation must promote safe, responsible, and legal gun ownership (2). Just as public health interventions are flattening the curve of the COVID-19 pandemic, the long-term benefit to our health system and our society equally justifies an intense, concerted effort to change behavior and end our nation's epidemic of violence.

References

- 1.Schwab C.W. Violence: America’s uncivil war. J Trauma. 1993;35:657–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnick S., Smith R.N., Beard J.H. Firearm deaths in America: can we learn from 462,000 lives lost? Ann Surg. 2017;266:432–440. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatchimonji J.S., Swendiman R.A., Seamon M.J., Nance M.L. Trauma does not quarantine: violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Surg. 2020;277:e53–e54. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bank M., O’Neill P., Prince J., Simon R., Teperman S., Winchell R. Early report from the greater New York chapter of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma on the COVID-19 crisis. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/covid19/nyc_chapter_acs_cot_covid19_crisis.ashx Available at:

- 5.Glass N.E., Riccardi J., Farber N.I., Bonne S.L., Livingston D.H. Disproportionally low funding for trauma research by the National Institutes of Health: a call for a National Institute of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88:25–32. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berwick D.M., Downey A.S., Cornett E.A. A national trauma care system to achieve zero preventable deaths after injury: recommendations from a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report. JAMA. 2016;316:927–928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauchner H., Rivara F.P., Bonow R.O. Death by gun violence—a public health crisis. JAMA. 2017;318:1763–1764. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]