Abstract

Background.

Risk assessment tools may help individuals gauge cancer risk and motivate lifestyle and screening behavior changes. Despite the evermore common availability of such tools, little is known about their potential utility in average-risk population approaches to cancer prevention.

Aims.

We evaluated the effects of providing personalized (vs. generic) information concerning colorectal cancer (CRC) risk factors on average-risk individuals’ risk perceptions and intentions to engage in three risk-reducing behaviors: CRC screening, diet, and physical activity. Further, we explored whether the receipt of CRC-specific risk assessment feedback influenced individuals’ breast cancer risk perceptions and mammography intentions.

Methods.

Using an online survey, N=419 survey respondents aged 50–75 with no personal or family history of CRC were randomized to receive an average estimate of CRC lifetime risk and risk factor information that was either personalized (treatment) or invariant/non-personalized (control). Respondent risk perceptions and behavioral intentions were ascertained before and after risk assessment administration.

Results.

No differences were observed in risk perceptions or behavioral intentions by study arm. However, regardless of study arm, CRC screening intentions significantly increased after risk assessment feedback was provided. This occurred despite a significant reduction in risk perceptions.

Conclusion.

Results support the role simple cancer risk assessment information could play in promoting screening behaviors while improving the accuracy of cancer risk perceptions.

Introduction

Cancer risk assessments are increasingly available to the public online. Although evidence suggests online risk assessment tools are a promising approach for communicating risk and promoting health behaviors in high risk individuals [1], little is known about the application of cancer risk assessments among those at average risk. Within colorectal cancer (CRC), the majority of new cases develop among “average risk” individuals, i.e., those with no known family history or other predisposing conditions (e.g., familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)) [2]. As much as 70% of CRC cases could be prevented through lifestyle modification and widespread screening [3]. Therefore, the identification and communication of modifiable risk factors – via cancer risk assessment – may help those at average risk to better understand their CRC risk and motivate risk-reducing behavioral intentions.

Despite the association between modifiable factors and CRC risk being particularly strong, most Americans do not engage in CRC risk-reducing behaviors and CRC remains the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States (U.S.) [4]. Therefore, the modification of lifestyle behaviors such as diet, physical activity, and routine cancer screenings [5], within the average risk population could substantially reduce CRC incidence, morbidity, and mortality.

While communicating risk may be an important step in shaping perceptions of disease risk, providing risk estimates alone may not be enough to drive health behaviors and behavior change intentions [6]. This may be especially true among individuals without a known family history who receive low or average numeric (e.g., <5%) or categorical (e.g., “unelevated”) risk estimates. When targeting this average – and therefore, relatively low risk – group for risk assessment, it may be particularly important to increase information saliency by emphasizing an individual’s modifiable health behaviors (as opposed to feedback focused on a calculated estimate of their risk). In general, personalized risk communication via numeric calculations has been shown to increase accuracy of risk perceptions [7–8], mobilize cancer screening utilization [9], and promote skin cancer preventive behaviors [10]. However, to our knowledge, no study has compared the effects of providing an average (i.e., non-personalized) risk estimate that incorporates personalized feedback related to an individual’s lifestyle behaviors (compared to generic information about risk factors) on risk perception and behavioral outcomes among average risk adults. This information is needed to isolate the impact of personalization based on risk factors in the risk assessment context and to understand whether feedback about individuals’ risk factors could be leveraged to promote CRC risk-reducing behaviors within the average risk population.

Another unknown outcome of cancer risk assessments is what influence, if any, receiving risk information for a specific cancer type has on risk perceptions and behavioral intentions related to another cancer type. An earlier study identified “novel spillover effects” whereby having a family history of one cancer was associated with altered disease perceptions of another cancer type [11]. Therefore, it is conceivable that heightened perceived risk for one cancer (following receipt of risk assessment results for that cancer type) may alter an individual’s perceived risk and behavioral intentions related to another type of cancer (via spillover effects).

The primary objective of this study was to experimentally evaluate whether perceptions of CRC risk are altered among average risk individuals receiving risk assessment feedback containing personalized information about one’s risk factors (treatment), compared to those receiving generic (non-personalized) information on risk factors (control). Secondary outcomes included evaluations of differential behavior change intentions (i.e., CRC screening, healthy diet, and physical activity) by receipt of personalized versus non-personalized information about CRC risk factors. We also assessed the presence of spillover effects by examining breast cancer risk perception and mammography screening intentions among female participants. Finally, in a post hoc analysis, we examine within group (pre/post) changes in risk perceptions and behavioral intentions.

Methods

Study Design

We used a pre-post parallel trial design to evaluate the effect of providing personalized risk factor information. An online survey was administered through Qualtrics, an internet-based survey and research company, in June 2017. Participants were randomized to receive either personalized or generic information on CRC risk factors. Randomization was carried out by Qualtrics using the Mersenne Twister algorithm, a widely accepted form of random number generation [12].

Prior to beginning the risk assessment tool, participants were queried for information necessary to determine sample eligibility (e.g., age, race, household income, and health history), and asked to complete questions measuring other sociodemographic characteristics including gender, education attainment, and marital status. Baseline (pre-intervention) behaviors were queried to ascertain cancer screening status and the presence of lifestyle risk factors (physical activity and diet) using previously developed items [13–15]. Specifically, six items assessed CRC screening for three testing modalities (i.e., fecal occult blood test (FOBT), colonoscopy, and sigmoidoscopy). Participants’ self-report from these questions were used to classify respondents into two groups: up-to-date for CRC screening (FOBT ≤ 1 year, or colonoscopy < 10 years ago, or sigmoidoscopy < 5 years ago); or otherwise, due for screening (i.e., not up-to-date). Female participants were queried two additional items related to mammography. Respondents who reported having a mammography within the last two years were classified as up-to-date; or otherwise, not up-to-date. Four items were used to obtain physical activity level, including the number of minutes per week engaged in physical activity. Vegetable consumption was ascertained (n=2 items) to determine the approximate number of servings per week of vegetables or leafy green salads eaten by each participant. According to ACS guidelines [14], levels of physical activity and vegetable consumption were classified as adequate if they met or exceeded recommendations; or otherwise, inadequate. Participant responses to questions related to cancer risk perceptions (i.e., perceived absolute, relative, and lifetime risk) and behavioral intentions for screening, physical activity, and diet were collected prior to and immediately following receipt of CRC risk information. All survey items required a response; therefore, there were no skipped or missing responses. Upon survey completion, participants could select from a variety of incentive options worth approximately $5.00. This study was approved by an Institutional Review Board following expedited review.

Sample and Survey Administration

Qualtrics acquired the sample from existing pools of research panel participants.1 Panelists were invited to participate via email and opted in by activating a survey link that directed them to the study consent form. Quota sampling was used to obtain a sample that is diverse with respect to household income and race. A balanced sample of White, Black/African American, and Hispanic/Latino/Spanish participants was requested. Respondents identifying as another race were not eligible to participate. Eligible panel participants included residents of the contiguous U.S. with the ability to read and comprehend English language. In addition, participants were screened for the following eligibility criteria: age 50–75 years old (age-eligible for CRC screening) and no personal or family history of CRC or other predisposing factors. Finally, respondents were removed from the sample if they responded incorrectly to any of the three “attention checks” (i.e., survey items instructing respondents to provide a specific response).

Risk Information

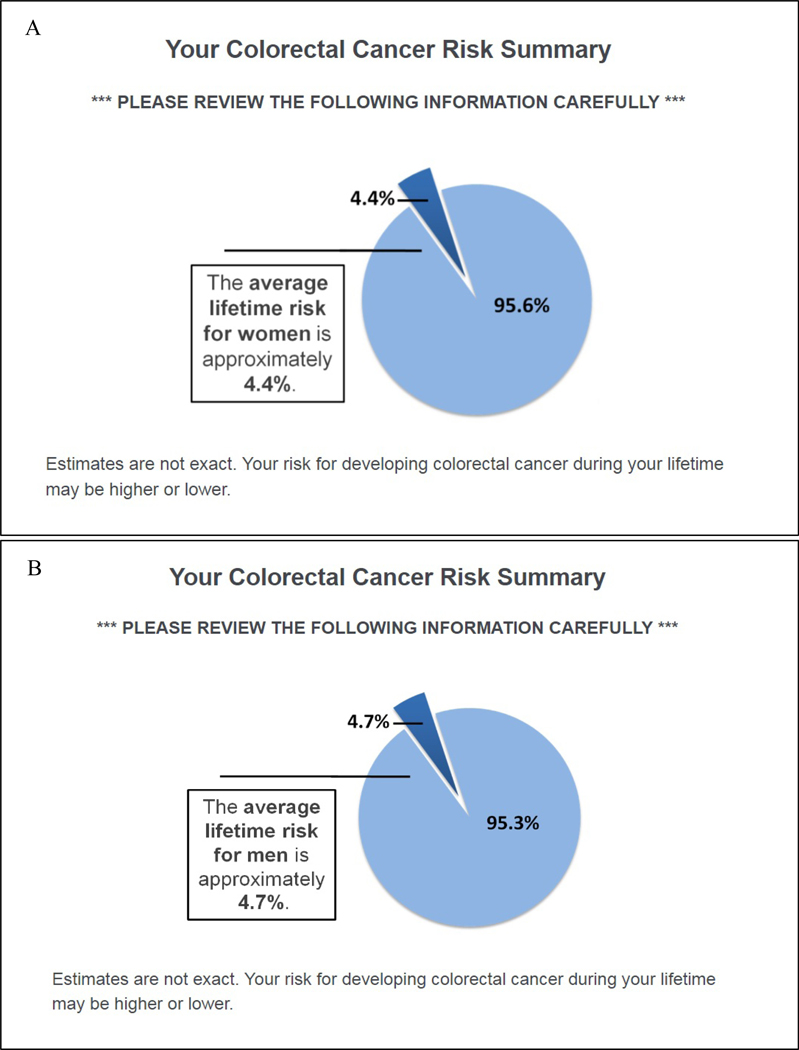

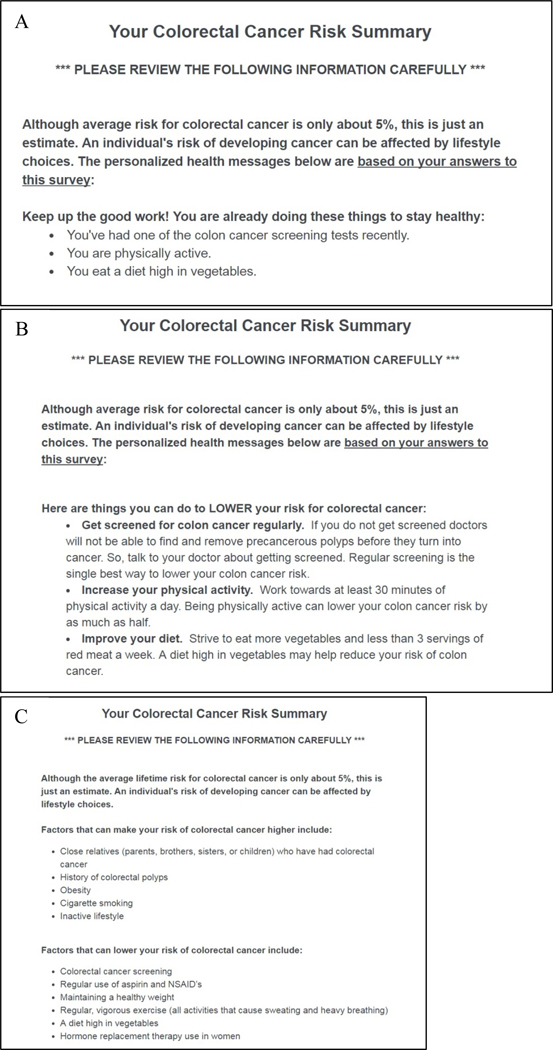

Because cancer risk assessments typically convey an individual’s calculated risk, all participants, regardless of study arm, received a gender-specific, population-level estimate of the average lifetime risk of developing CRC in the U.S. (Figure 1) [16]. Risk factor information was presented immediately following the numeric risk estimates, according to study group. Participants randomized to the control group received a static summary describing 11 factors that can increase or lower risk of CRC (Figure 2c) [17]. In contrast, risk factor information provided within the treatment group was tailored to each respondent’s actual risk profile (i.e., the presence/absence of risk factors as reported by each respondent).

Figure 1.

Average Lifetime Risk for Colorectal Cancer

Note. Figure 1 depicts lifetime risk for men (A) and women (B).

Figure 2.

Risk Factor Messages

To test the influence of personalized (vs. generic) risk factor information on risk perception and behavioral intentions, three modifiable CRC risk-reducing behaviors (screening, physical activity, and diet) were chosen from the total summary provided in control group. The specific content of the individually tailored risk summary was adapted from existing online risk assessment tools [17–18]. Each targeted behavior was framed as either a protective (Figure 2a) or risk (Figure 2b) factor based on participant reported engagement in that behavior. Any behaviors listed as a risk factor included a behavior change recommendation. Each risk factor message also included information about the risk-reducing consequences of the behavior. The wording of these statements was developed based on Prospect Theory [19], and in accordance with prior research demonstrating that gain-framed messages tend to be more effective in promoting prevention behaviors and intentions, including diet [20] and physical activity [21], whereas loss-framed behaviors are more effective in promoting diagnostic behaviors and intentions (e.g., cancer screenings) [22].

Outcome Measures

Cancer Risk Perceptions.

The primary outcome, CRC numeric lifetime risk, was assessed by asking, “On a scale from 0 to 100 %, how would you rate the probability that you will develop colorectal cancer in the future?” with an open-response of 0–100%. “How likely is it that you will get colorectal cancer at some point in the future?” was used to assess absolute risk using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “very unlikely” to “very likely.” Relative risk was also measured with the question, “How do you think your chance of developing colorectal cancer in the future compares to the average person of your gender and age?” with responses ranging from “much lower” to “much higher” on a five-point Likert scale. These three individual items were also adapted to assess perceived absolute, relative, and numeric lifetime risk of breast cancer among female participants.

Dichotomous measures of accuracy were created for reported numeric lifetime risk of colorectal and breast cancers. Accurate lifetime risk of CRC was defined as a response between four and five percent [4]. The average lifetime risk of women developing breast cancer is approximately 12% [23]; therefore, responses between 10–15% were coded as accurate. The wider range of reported breast cancer risk was considered accurate since no estimates were provided to respondents.

Behavior Change Intentions.

Behavior change intentions related to CRC screening, mammography screening, physical activity, and diet were assessed pre-and post-intervention. Based on previous CRC screening research [24], respondents were asked a single item adapted for each behavior, “How likely are you to [get screened for colorectal cancer, improve your diet, and increase your physical activity] in the next 6 months?” on a five-point Likert scale “not at all to “extremely.” Participants classified as up-to-date on CRC or mammography screening based on their prior responses about screening history, were asked about screening intentions with an alternative ending, “…when you are due to screen again?”

Analyses

Independent samples t-tests were used to test differences between treatment and control groups in the primary outcome (i.e., post-intervention CRC numeric lifetime risk perception). Subsequent independent samples t-tests and chi-squared tests of association were used to test for differences between intervention groups in secondary outcomes (e.g., absolute and relative risk perceptions, behavioral intentions, and breast cancer risk perception at post-intervention). To explore within group differences, a series of ad hoc analyses were performed using paired samples t-tests and McNemar’s tests to detect changes within each group (from pre-to post-intervention). Analyses controlling for pre-test risk perceptions, pre-test behavioral intentions, and interaction effects between risk factor presence and study arm were performed and did not produce different outcomes (data not shown).

Results

Sample

Approximately 63,500 panelists were sent survey invitations. Among those solicited for participation, 1,448 panelists clicked on the survey link and consented to participate, including n=671 ineligible panelists per study criteria and an additional n=220 per sample quota criteria (i.e., over quotas). Among the remaining 557 respondents, 71 failed to complete the survey (13%) and an additional 67 were removed for failing an attention check (i.e., not providing the requested response) (12%). A total of n=419 completed surveys were collected, resulting in a 75.2% completion rate among those who consented and were eligible for participation.

Participants were 58.5 years old on average (sd=6.3). Sixty-seven percent of the sample were female (n=279). As designed, the sample included equal proportions of White, Black, and Hispanic participants (33% each). Almost half of respondents were married (48%) and college educated (48%). Less than half were employed (41%) and 43% reported an annual household income of $50,000 or higher. Participants on average had two out of the three targeted CRC risk factors. Overall, 50% of participants were not up-to-date with CRC screening, 43% failed to get enough physical activity, and 83% had inadequate vegetable consumption per guidelines.

Colorectal Cancer Risk Perceptions

No significant differences were observed in any of the post-intervention CRC risk perception measures between the treatment and control groups (Table 1). However, within both groups, the average numeric lifetime risk reported was significantly reduced at post-test (compared to pre-test) (t(211) = −5.576, p < .001 and t(206) = −4.848, p < .001 for treatment and control, respectively) and indicated greater accuracy in lifetime risk (χ2(1) = 87.258, p < .001 and χ2(1) = 60.800, p < .001, for treatment and control, respectively).

Table 1.

Risk Perceptions and Behavioral Intentions by Group at Pre-Intervention and Post-Intervention (N=419)

| Variable | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | Within Groups3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control n (%) | Treatment n (%) | Control n (%) | Treatment n (%) | Between Groups1,2 p | Control p | Treatment p | |

| Colorectal Cancer Risk Perceptions | |||||||

| Mean Lifetime Risk (sd) (0–100%) | 18.9 (21.1) | 17.8 (20.9) | 11.0 (16.6) | 11.0 (16.0) | 0.999 | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Accurate Lifetime Risk (N (%))a | 15 (7.2) | 10 (4.7) | 92 (44.4) | 103 (48.6) | 0.396 | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Mean Absolute Risk (sd)b | 2.1 (0.9) | 2.2 (1.0) | 2.2 (0.9) | 2.4 (1.0) | 0.062 | 0.170 | 0.008** |

| Mean Relative Risk (sd)c | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.2 (1.0) | 0.378 | 0.93 | 0.071 |

| Breast Cancer Risk Perceptionsd | |||||||

| Mean Lifetime Risk (sd) (0–100%) | 26.2 (24.4) | 22.5 (24.0) | 22.1 (23.1) | 20.6 (24.1) | 0.606 | 0.002** | 0.034* |

| Accurate Lifetime Risk (N (%))e | 15 (14.0) | 15 (13.0) | 12 (11.2) | 14 (12.2) | 0.824 | 0.629 | 1.000 |

| Mean Absolute Risk (sd)b | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.0) | 0.492 | 0.058 | 0.154 |

| Mean Relative Risk (sd)c | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.0) | 0.474 | 0.433 | 0.347 |

| Behavior Change Intentionsf | |||||||

| Mean CRC Screening Intention (sd) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.9 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.5) | 0.278 | 0.000*** | 0.000*** |

| Mean Physical Activity Intention (sd) | 3.1 (1.2) | 3.1 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.2 (1.2) | 0.867 | 0.031* | 0.180 |

| Mean Diet Intention (sd) | 3.2 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.3 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.2) | 0.917 | 0.175 | 0.471 |

| Mean Mammography Intention (sd)d | 3.7 (1.4) | 3.7 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.4) | 3.8 (1.5) | 0.754 | 0.032* | 0.338 |

Note.

Abbreviations: CRC=colorectal cancer

Between groups: post-test only comparison between treatment vs. control (independent samples t-tests for continuous outcomes and chi-squared tests of association for categorical outcomes)

Analyses controlling for pre-test risk perceptions, pre-test behavioral intentions, and interaction effects between risk factor presence and study arm were performed and did not produce different outcomes (data not shown).

Within groups: pre-test vs. post-test (paired samples t-tests for continuous outcomes and McNemar’s tests for categorical outcomes) within each group (control and treatment)

Between 4–5% coded as accurate

Measured on a 5 point Likert scale, Very Unlikely (1) to Very Likely (5)

Measured on a 5 point Likert scale, Much Lower (1) to Much Higher (5)

Among n=279 women

Between 10–15% coded as accurate

Measured on a 5 point Likert scale, Not At All (1) to Extremely (5) likely to make positive health change

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

The single item indicator of absolute risk of CRC was approaching statistical significance (t(417) = −1.874, p = .06), with higher risk reported in the treatment group, compared to control (Table 1). Post-hoc tests assessing pre-post change in each group found a significant increase in absolute risk in the treatment group at post-test, compared to pre-test (t(211) = 2.677, p = .008). Relative risk trended towards a significant decrease within the treatment group (t(211) = −1.818, p = .07). There were no significant differences in absolute or relative risk perception within the control group.

Breast Cancer Risk Perceptions

There were no significant differences observed in any of the post-intervention breast cancer risk perception measures between the treatment and control groups (Table 1). There were no significant differences within groups in absolute or relative perceptions of breast cancer risk, although a decrease in absolute risk at post-invention was approaching significance within the control group (t(137) = −1.914, p = .06). Within both the treatment and control groups, the average numeric lifetime risk of breast cancer reported was significantly lower at post-test compared to pre-test (t(140) = −2.142, p =.034 and t(137) = −3.111, p = .002, for treatment and control, respectively); accuracy in numeric lifetime risk of breast cancer, however, did not change significantly within either group. Post-hoc McNemar’s tests revealed that the overall proportion of individuals who overestimate their lifetime risk of breast cancer significantly decreased, while the overall proportion of individuals who underestimate significantly increased (χ2(1) = 7.902, p < .01 and χ2(1) = 6.919, p < .01, overestimate and underestimate, respectively) [data not shown].

Behavior Change Intentions

Post-test intentions for CRC screening, diet, and physical activity did not differ significantly by study arm (Table 1). However, behavioral intentions increased for screening, diet, and physical activity among 25–30% of all participants (data not shown). In post-hoc analyses of pre-post change significant increases in CRC screening intentions (t(211) = 3.961, p < .001 and t(206) = 4.783, p < .001 for treatment and control, respectively) were identified. Physical activity intentions increased within the control group only (t(206) = 2.175, p = .031), while diet intentions did not significantly change within either group. Post-test mammography screening intentions did not differ significantly by intervention arm. Intentions for mammography screening increased within the control group (t(137) = 2.166, p = .032). There were no significant changes within the treatment group.

Discussion

Although the hypothesized differences between study arms in post-intervention risk perceptions and behavioral intentions were not supported, several significant within group differences were observed. Specifically, perceived numeric lifetime risk of CRC lowered and seemed to spillover onto female participants’ perceived lifetime risk of breast cancer. Results also suggest that cancer risk feedback may facilitate screening intentions regardless of whether the provided risk information is personalized. Taken together, findings suggest that risk communication practices may not need to provide personalized content to improve accuracy of perceived numeric lifetime risk and drive screening intentions among those at average risk of CRC.

Numeric lifetime risk of CRC reported post-intervention was significantly lower than pre-intervention in both intervention arms. This reduction reflects greater accuracy in perceived lifetime risk and adds to the body of literature demonstrating improved risk perception accuracy after risk assessment feedback [7–8]. Additional research is needed to identify the cognitive and behavioral implications of altering lifetime risk perception accuracy among average risk individuals. Within our sample, health behavior intentions were not negatively impacted, despite significant reductions in cancer risk perceptions. Future studies should further evaluate whether increased risk perception accuracy among average risk individuals is beneficial or detrimental (i.e., leads to a false sense of security and impedes adoption of health behaviors).

Women’s perceived lifetime risk of breast cancer also significantly decreased at post-intervention (compared to pre-intervention), regardless of study arm. This novel finding of change in women’s perceived lifetime risk of breast cancer following CRC-specific risk feedback may represent an unintended, and potentially adverse, consequence of providing cancer type-specific assessment results. Future research is warranted to replicate these results. In the meantime, researchers and professionals using cancer risk assessments in practice should be cognizant of the potential for such spillover effects.

On the other hand, CRC screening intentions significantly increased at post-intervention (compared to pre-intervention), again regardless of group. This finding suggests that cancer risk assessments may be useful in promoting screening behavioral intentions among average risk individuals regardless of whether the content is personalized. Within the control group, mammography screening intentions also increased post-intervention. This is somewhat surprising given both perceived lifetime and absolute risk decreased in this group (although the latter did not reach statistical significance). This result may indicate that generic feedback on specific risk factors (including screening behavior) is more likely to produce spillover intentions on other types of cancer screening. Findings such as these highlight the importance of explicitly testing for spillover effects as interventions that can successfully change multiple behaviors are more efficient than those targeting one behavior at a time.

While results related to screening intentions are encouraging, there were limited effects observed on diet and physical activity intentions. The null results related to diet intentions is particularly worrisome given that dietary habits are strongly associated with CRC risk and an unhealthy diet was the most prevalent risk factor identified in this sample. It is possible that screening is perceived differently, e.g., a “one and done” behavior to reduce risk, as opposed to an ongoing, daily change in lifestyle. Alternatively, screening was the only negatively-framed message; therefore, behavioral intentions of average risk individuals may be influenced more by negatively-framed prevention messages, although this would contrast prior work supporting an advantage of gain-framed messages on general preventive behavioral intentions [21]. These results underscore the need for future research on the role risk information plays in promoting behavior change intentions, and in addition, the relative difficulty public health practitioners face in “moving the needle” on lifestyle modifications among individuals without a family history of cancer.

Finally, the null findings between trial arms may be partially explained by the average risk (and thus by definition low risk) status of the study sample. This supposition is bolstered by the fact that perceived numeric lifetime risk of CRC decreased in both groups post-intervention. As such, our findings highlight a divergence from prior research suggesting that the provision of personalized risk feedback is more successful in motivating changes in lifestyle behaviors [25]. However, the single item used to indicate absolute risk significantly increased from pre-to post-intervention within the treatment group and was approaching statistical significance (t(417) = −1.874, p = .06), with higher risk reported in the treatment group, compared to control (as hypothesized). This result offers some evidence pointing to a potentially beneficial role of personalized information in promoting change (via increased non-numeric perception of risk), even when provided in combination with average and relatively low estimates of lifetime risk.

Strengths and Limitations

Responses from this internet panel sample may not generalize to populations that do not engage in online research. Furthermore, survey responses regarding behavioral intent do not necessarily translate into actual behavioral change and the cross-sectional nature of these data do not allow us to ascertain if participants acted upon their intentions. Finally, the lifetime risk estimates provided in this study were based on the average lifetime risk of men and women in the U.S. and were not personalized for each respondent. Although the actual estimated range of lifetime risk in an average risk sample would be relatively small, providing individualized risk estimates may yield different results.

The limitations of this study are balanced by several strengths. First, the sample is economically and racially diverse which enhances the ability to generalize findings to such populations, an uncommon trait of internet samples. In addition, the sample consists of individuals with average risk for CRC, a relatively understudied, yet critical population to study cancer risk assessment and preventive behaviors, since the majority of CRC will occur among individuals without a family history [2].

Conclusion

This study highlights the complexity of cancer risk perceptions among those at average risk. Our findings suggest that cancer risk assessments alter risk perceptions and facilitate screening intentions. These results shed new light on the potential utility of cancer risk assessments as vehicles for improving the accuracy of individuals’ cancer risk perceptions while promoting risk-reducing behaviors.

Impact Statement.

Providing cancer risk assessment information may decrease individuals’ perceptions of cancer risk to more realistic levels while simultaneously facilitating screening intentions among an average risk population, regardless of whether provided risk information is personalized.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this study was provided in part by a predoctoral training award from the Susan G. Komen Foundation (GTDR14302086) and a National Cancer Institute T32 award (2T32CA093423).

Footnotes

Qualtrics outsourced recruitment to partner companies with established panels.

Contributor Information

Carrie A. Miller, NCI T32 Postdoctoral Scholar, Department of Health Behavior & Policy, Massey Cancer Center, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Jennifer Elston Lafata, Division of Pharmaceutical Outcomes and Policy, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, Co-lead, UNC Cancer Care Quality Initiative, UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, Associate Director, UNC Institute for Healthcare Quality Improvement.

Maria D. Thomson, Department of Health Behavior and Policy, Graduate Program Director, Social and Behavioral Sciences Program, School of Medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University.

References

- 1.Wang Catherine, Sen Ananda, Ruffin Mack T., Nease Donald E., Gramling Robert, Acheson Louise S., O’Neill Suzanne M., Rubinstein Wendy S., and Family Healthware Impact Trial (FHITr) Group. 2012. Family history assessment: impact on disease risk perceptions. American journal of preventive medicine, 43(4): 392–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch Henry T. and de la Chapelle Albert. 2003. Hereditary colorectal cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 348(10): 919–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colditz Graham A. and Stein Cynthia. 2004. Handbook of cancer risk assessment and prevention. Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. 2018. Key Statistics for Colorectal Cancer, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- 5.American Cancer Society. 2017. Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures 2017–2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmberg Christine and Parascandola Mark. 2010. Individualised risk estimation and the nature of prevention. Health, Risk & Society, 12(5): 441–452. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emmons Karen M., Wong Mei, Puleo Elaine, Weinstein Neil, Fletcher Robert, and Colditz Graham. 2004. Tailored computer-based cancer risk communication: correcting colorectal cancer risk perception. Journal of health communication, 9(2): 127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein Neil D., Atwood Kathy, Puleo Elaine, Fletcher Robert, Colditz Graham, and Emmons Karen. 2004. Colon cancer: risk perceptions and risk communication. Journal of health communication, 9(1): 53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards Adrian, Evans Rhodri, Hood Kerry, and Elwyn Glyn J.. 2006. Personalised risk communication for informed decision making about taking screening tests. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glanz Karen, Volpicelli Kathryn, Jepson Christoper, Ming Michael E., Schuchter Lynn M., and Armstrong Katrina. 2014. Effects of tailored risk communications for skin cancer prevention and detection: The PennSCAPE randomized trial. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, cebp. 24(2): 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubinstein Wendy S., O’Neill Suzanne M., Rothrock Nan, Starzyk Erin J., Beaumont Jennifer L., Acheson Louise S., Wang Catherine, Gramling Robert, Galliher James M., and Ruffin Mack T.. 2011. Components of family history associated with women’s disease perceptions for cancer: a report from the Family Healthware™ Impact Trial. Genetics in Medicine, 13(1): 52–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amakawa Kazuki. 2017. The application of Discrete Mathematics in Algorithm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones Resa M., Mongin Steven J., Lazovich DeAnn, Church Timothy R., and Yeazel Mark W.. 2008. Validity of four self-reported colorectal cancer screening modalities in a general population: differences over time and by intervention assignment. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 17(4): 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kushi Lawrence H., Doyle Colleen, Marji McCullough Cheryl L. Rock, Wendy Demark‐Wahnefried Elisa V. Bandera, Gapstur Susan, Patel Alpa V., Andrews Kimberly, and Gansler Ted. 2012. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 62(1): 30–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Department of Agriculture, C. g. 2017. All About the Vegetable Group, from https://www.choosemyplate.gov/vegetables

- 16.American Cancer Society. 2014. Lifetime Risk of Developing or Dying From Cancer, from http://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancerbasics/lifetime-probability-of-developing-or-dying-from-cancer

- 17.Freedman Andrew N., Slattery Martha L., Rachel Ballard-Barbash Gordon Willis, Cann Bette J., Pee David, Gail Mitchell H., and Pfeiffer Ruth. 2008. Colorectal cancer risk prediction tool for white men and women without known susceptibility. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27(5): 686–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colditz Graham, Atwood KA, Emmons Karen, Monson RR, Willett WC, Trichopoulos W,D, and Hunter DJ. 2000. Harvard report on cancer prevention volume 4: Harvard Cancer Risk Index. Cancer Causes & Control, 11(6): 477–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tversky Amos and Kahneman Daniel. 1980. The Framing of Decisions and the Rationality of Choice: DTIC Document. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brug Johannes, Ruiter Robert A. C., and Van Assema Patricia. 2003. The (ir) relevance of framing nutrition education messages. Nutrition and Health, 17(1): 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallagher Kristel M., and Updegraff John A.. 2012. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: a meta-analytic review. Annals of behavioral medicine, 43(1): 101–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrer Rebecca A., Klein William M., Zajac Laura E., Land Stephanie R., and Ling Bruce S.. 2012. An affective booster moderates the effect of gain-and loss-framed messages on behavioral intentions for colorectal cancer screening. Journal of behavioral medicine, 35(4): 452–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute. 2012. Breast Cancer Risk in American Women, from https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/risk-fact-sheet

- 24.Vernon Sally W., Meissner Helen, Klabunde Carrie, Rimer Barbara K., Ahnen Dennis J., Bastani Roshan, Mandelson Margaret T., Nadel Marion R., Sheinfeld-Gorin Sherri, and Zapka Jane. 2004. Measures for ascertaining use of colorectal cancer screening in behavioral, health services, and epidemiologic research. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 13(6): 898–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noar Seth M., Benac Christina N., and Harris Melissa S.. 2007. Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological bulletin, 133(4): 673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]