Abstract

Introduction:

Cleaning and shaping are necessary for the delivery of irrigants and medicaments to the apical third of the canal. Standard treatment irrigation generally uses a conventional needle and some frequency of sonic activation. The GentleWave® System (GWS) combines irrigant delivery with Multisonic activation. This randomized clinical trial aimed to determine if the GWS significantly decreases the incidence and intensity of postoperative pain.

Methods:

Patients used a numerical rating scale (NRS) to record their pain level at the six-hour timepoint before treatment. All participants were randomly divided into two groups and were blind to the treatment they received. The standard (control) group received endodontic treatment with conventional side-vented needle irrigation and ultrasonic activation. The 2nd group received treatment with the GWS. Following treatment, patients used an NRS to record their pain level at six, 24, 72, and 168 hours

Results:

72.2% of standard treatment patients and 83.3% of GWS patients experienced at least one occurrence of postoperative pain. The highest pain intensity level for both treatments occurred at the six-hour post-treatment timepoint. All pain decreased with time after the six-hour post-treatment time point (p < 0.0000001237).

Conclusion:

There was no significant difference in the incidence or intensity of postoperative pain following either treatment group. However, both groups reported a statistically significant decrease in pain with time.

Keywords: Endodontics, Postoperative pain, GentleWave, Irrigation, Incidence, Intensity

INTRODUCTION

There are many reasons why a tooth would need root canal treatment. Root canal treatment is indicated once a tooth reaches a level of inflammation or infection where healing can no longer occur. This inflammation or infection can eventually lead to periradicular disease. The goal of root canal treatment is to clean, shape, disinfect, and obturate all canal systems within the tooth to prevent periradicular disease from occurring or to eliminate the etiology of existing periradicular disease. Proper instrumentation of the canal system allows for adequate delivery of irrigants. Irrigants not only lubricate and disinfect the canal system, they also aid in contaminant and debris removal (1).

Generally, the safest and most common method for the delivery of irrigants is the conventional side-vented needle (2). However, there are supplementary delivery methods available that can be used depending on the situation. The addition of sonic and ultrasonic irrigant activation increases the efficiency of debridement and disinfection. The GentleWave® System (GWS, Sonendo, Inc, Laguna Hills, CA) is a novel irrigation system that combines irrigant delivery with a multisonic, broad-spectrum energy activation. The GWS allows for the complete cleaning and disinfection of the canal system including uninstrumented accessory canals and isthmuses (3).

Between appointments or hours to days following the completion of treatment, postoperative pain can occur due to acute inflammation (4). The factors most commonly responsible for interappointment or postoperative pain include mechanical preparation and obturation beyond the apex, bacteria not eliminated during primary disinfection, and the extrusion of irrigants beyond the apex (5). With a conventional side-vented needle, the depth of needle penetration and the pressure placed on the syringe plunger are both under operator control, which can be adjusted to avoid irrigant extrusion. The GWS, on the other hand, avoids irrigant extrusion by relying on the negative pressure created by a suction component within the device (6). Only two clinical studies to date have surveyed the occurrence of postoperative pain following treatment using the GWS (7, 8). The purpose of this randomized clinical trial was to determine whether treatment using the GWS significantly decreases the incidence or intensity of postoperative pain following root canal treatment compared to a standard irrigation protocol. The null hypothesis is that there is no difference in the incidence or intensity of postoperative pain following instrumentation and irrigation using a standard endodontic treatment protocol versus instrumentation and irrigation using the GWS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This single-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial was approved by an Institutional Review Board (STUDY00003030) and was also registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database (NCT03635515). All patients signed informed consent and HIPAA authorization forms after agreeing to participate in the study. In calculating the sample size necessary to achieve a power of 80%, several studies were examined to determine not only their sample sizes but their incidences of endodontic postoperative pain. Using the Pak et al 2011 and Sathorn et al 2008 systematic reviews, as well as the Sigurdsson et al 2018 study on the GWS, the anticipated incidence of postoperative pain was determined to be 60% for the standard treatment and 15% for the GWS treatment (9, 10, 8). A sample size calculator using these variables found a sample size of 34 patients (17 per group) was necessary to show statistical significance. The Institutional Review Board restricted recruitment size to 50 patients (25 per group), allowing for loss to follow-up.

Three 2nd year graduate endodontics residents performed all treatments. The target population of the study included patients of the graduate endodontics clinic requiring root canal therapy. Inclusion criteria included: (i) patients who were 18 years of age or older, with a molar or premolar requiring root canal therapy and (ii) teeth with fully formed apices. Exclusion criteria included: (i) patients under the age of 18 or those patients incapable of giving informed self-consent, (ii) teeth with immature or opened apices, (iii) teeth with apices in the maxillary sinus or those teeth where the apical lesion had eroded the bone of the maxillary sinus floor, (iv) teeth with internal or external resorption, and (v) teeth with carious lesions or deficient crowns that could not be restored prior to accessing the pulp chamber. Randomization software was used to generate a list for random participant assignment as they were recruited. This randomization was performed by an operator not involved in the study.

Pain measurement

Prior to treatment, a diagnostic exam was performed which included a cold test, percussion, palpation, mobility, periodontal probing, and a radiographic exam. The patients were then asked to record the level of pain experienced at the six-hour timepoint prior to treatment. If the root canal treatment required two appointments, the six-hour pre-treatment pain measurement was taken for the six hour time period prior to the second appointment. Pre- and post-treatment pain assessments were made using a 0-100 numerical rating scale (NRS)-41 for pain. The ‘0’ mark represented ‘no pain’ and the ‘100’ mark represented ‘the worst pain imaginable’, with 39 additional numeric markings between ‘0’ and ‘100’. The patients were instructed to write in their numerical pain rating if it was not on the pain scale. Along with the numeric ratings, the pain assessments included Wong-Baker FACES, as well as verbal descriptors indicating low, mild, moderate, high, and very high/severe pain. For this study, scores 0-19 represented low pain, 20-39 was mild pain, 40-59 was moderate pain, 60-79 was high pain, and 80-100 was very high or severe pain. The following characteristics were recorded for each patient who returned their survey: age, sex, pulpal and apical diagnoses, tooth type and arch, rotary file system, master apical canal size, type of sealer used, and obturation technique.

Clinical Treatment

To blind patients to the treatment they were receiving, the GWS was placed in the treatment operatory regardless of which treatment arm was performed and high speed suctions were run for the entirety of the appointment to mask the sound of the GWS. For both groups, local anesthetic was delivered via infiltration for maxillary teeth using a 30 gauge needle and via inferior alveolar nerve block or Gow-Gates for mandibular teeth using a 27 gauge needle. Following confirmation of profound anesthesia by cold testing, a rubber dam was placed to isolate the tooth being treated. Prior to accessing the pulp chamber, all caries, defective restorations, and deficient crowns were removed. A composite build-up was placed, if necessary, to maintain isolation then straight-line access was achieved. A size (#) 8 or 10 K-file and the Root ZX II electric apex locator (J. Morita Corp, Osaka, Japan) were used to determine the working length, which was then verified with a periapical radiograph. If either group required a second appointment for treatment completion, Ultracal (Ultradent Products, Inc, South Jordan, UT) calcium hydroxide paste was placed as an intracanal inter-appointment medicament following instrumentation and irrigation using a conventional side-vented needle. For any GWS case requiring two appointments, the GWS procedure was performed at the second appointment.

For the control group (standard endodontic treatment), following working length determination, all canals were instrumented using hand and rotary files to at least a size and taper of 25/04 to within ½ to 1 mm short of the apical terminus. The treating clinician determined the appropriate final apical canal size based on tooth morphology. Canals were prepared in a crown down fashion to avoid debris and irrigant extrusion. Between each file, 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) was used to disinfect the canals and flush debris. Recapitulation with a #8 or #10 K-file was performed to maintain patency. Following instrumentation for one appointment treatments or after re-accessing the tooth at the second appointment, NaOCl was ultrasonically activated for 30 seconds in each canal using the Spartan Wave™ Piezo ultrasonic unit (Obtura Spartan Endodontics, Algonquin, IL). Each tooth was then flushed with 3 ml of 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 1 minute followed by a rinse of 5.25% NaOCl. A total of at least 10 ml of NaOCl was used for each procedure. A final rinse of 1 ml of 95% ethanol was used prior to obturation of all teeth except for those sealed with bioceramic sealers. Canals were then dried and filled with gutta-percha and a sealer of the clinician’s choice.

For the GWS group, following working length determination, all canals were instrumented to at least a minimum size and taper of 20/04 or 06 to within ½ to 1 mm short of the apical terminus. The treating clinician determined the appropriate final canal size based on tooth morphology. Canals were prepared in a crown down fashion to avoid debris and irrigant extrusion. Between each file, 5.25% NaOCl was used to disinfect the canals and flush debris. Recapitulation with a #8 or #10 K-file was performed to maintain patency. Following canal instrumentation, or after re-accessing the tooth at the second appointment, the recommended manufacturer’s protocol was followed for the operation of the GWS. The GWS occlusal platform matrix was placed into the access cavity to verify the correct access opening size. Kool-dam heatless liquid dam (Pulpdent, Watertown, MA) was then placed on the GWS occlusal matrix to build an occlusal platform which supports the GWS handpiece and seals the access opening. The tooth, with the occlusal platform covering the access opening, was then re-accessed to the same size as the original access opening. For molars, the GWS depth gauges were used to determine the proper sealing cap for the GWS handpiece. Following calibration and cycle selection, the GWS handpiece was positioned on the tooth for the entirety of the treatment cycle. Canals were then dried and filled with gutta-percha and a sealer of the clinician’s choice.

Once obturation and temporary or permanent restoration were completed for teeth in both groups, all patients were given four additional NRS pain assessments to take home and were instructed to record their pain levels at six, 24, 72, and 168 hours post-treatment. Patients were instructed to use a rescue medication for any unbearable pain and to record the drug doses. The rescue medication recommended was the regimen introduced by Menhinick et al in 2004, which includes 600mg ibuprofen every six hours with the addition of 1000mg acetaminophen if ibuprofen alone was not sufficient for pain relief (11).

Statistical Analysis

Due to the sample size, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was run with a significance level of 0.05 for pain measurements recorded at six, 24, 72, and 168 hours. A linear mixed-effects model was used to compare the groups across time.

RESULTS

A total of 44 patients were recruited for this study between January and June of 2019. All patients who were recruited received their designated treatment. 36 patients (18 in each group) returned their NRS pain assessments for a recall rate of 81.8%. Four patients in each group did not return their pre and postoperative surveys and were lost to follow-up. No significant difference was found between age, sex, pulpal and apical diagnoses, tooth type and arch, rotary file system, master apical canal size, type of sealer used, or obturation technique. (See Table 1)

Table 1:

Statistical Data Characteristics

| Data characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GentleWave | Standard | All | p-value | |

| n | 18 | 18 | 36 | |

| Age | 46.67 (±17.91) | 56 (±13.75) | 51.33 (±16.43) | 0.089 |

| Gender (=Female) | 8 (44.44%) | 6 (33.33%) | 14 (38.89%) | 0.732 |

| Dx | 0.766 | |||

| =AIP/CAA | 1 (5.56%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (2.78%) | |

| =AIP/Normal | 1 (5.56%) | 1 (5.56%) | 2 (5.56%) | |

| =Necrotic/AAA | 1 (5.56%) | 2 (11.11%) | 3 (8.33%) | |

| =Necrotic/AAP | 2 (11.11%) | 1 (5.56%) | 3 (8.33%) | |

| =Necrotic/CAA | 3 (16.67%) | 1 (5.56%) | 4 (11.11%) | |

| =Necrotic/SAP | 4 (22.22%) | 6 (33.33%) | 10 (27.78%) | |

| =PT/AAP | 2 (11.11%) | 1 (5.56%) | 3 (8.33%) | |

| =PT/SAP | 1 (5.56%) | 2 (11.11%) | 3 (8.33%) | |

| =RP/SAP | 1 (5.56%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (2.78%) | |

| =SIP/Normal | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (11.11%) | 2 (5.56%) | |

| =SIP/SAP | 2 (11.11%) | 2 (11.11%) | 4 (11.11%) | |

| Mandibular teeth | 14 (77.78%) | 8 (44.44%) | 22 (61.11%) | 0.087 |

| Molar | 14 (77.78%) | 12 (66.67%) | 26 (72.22%) | 0.709 |

| Treatment (=Initial) | 15 (83.33%) | 15 (83.33%) | 30 (83.33%) | > 0.999 |

| # of 2 appointment treatments | 15 (83.33%) | 10 (55.56%) | 25 (69.44%) | 0.075 |

| Rotary file system | 0.533 | |||

| =Endo Sequence Scout | 6 (33.33%) | 5 (27.78%) | 11 (30.56%) | |

| =Vortex Blue | 11 (61.11%) | 13 (72.22%) | 24 (66.67%) | |

| =Vtaper | 1 (5.56%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Master apical file size | 27.54 (±4.92) | 30.32 (±3.20) | 28.93 (±4.33) | 0.054 |

| =20.04 | 2 (11.11%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (5.56%) | |

| =20.06 | 1 (5.56%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (2.78%) | |

| =25.04 | 5 (27.78%) | 2 (11.11%) | 7 (19.44%) | |

| =30.04 | 9 (50.00%) | 14 (77.78%) | 23 (63.89%) | |

| =40.04 | 1 (5.56%) | 1 (5.56%) | 2 (5.56%) | |

| Sealer | 0.235 | |||

| =AH Plus | 8 (44.44%) | 4 (22.22%) | 12 (33.33%) | |

| =Brassler BC | 6 (33.33%) | 7 (38.89%) | 13 (36.11%) | |

| =Brassler BC HiFlow | 4 (22.22%) | 3 (16.67%) | 7 (19.44%) | |

| =Kerr | 0 (0.00%) | 3 (16.67%) | 3 (8.33%) | |

| =Roths 801 | 0 (0.00%) | 1 (5.56%) | 1 (2.78%) | |

| Obturation technique (=MCW) | 16 (88.89%) | 14 (77.78%) | 30 (83.33%) | 0.655 |

AAA-Acute apical abscess AAP-Asymptomatic apical periodontitis AIP-Asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis

CAA-Chronic apical abscess MCW-Modified continuous wave PT-Previously treated RP-Reversible pulpiti

SAP-Symptomatic apical periodontitis SIP-Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis

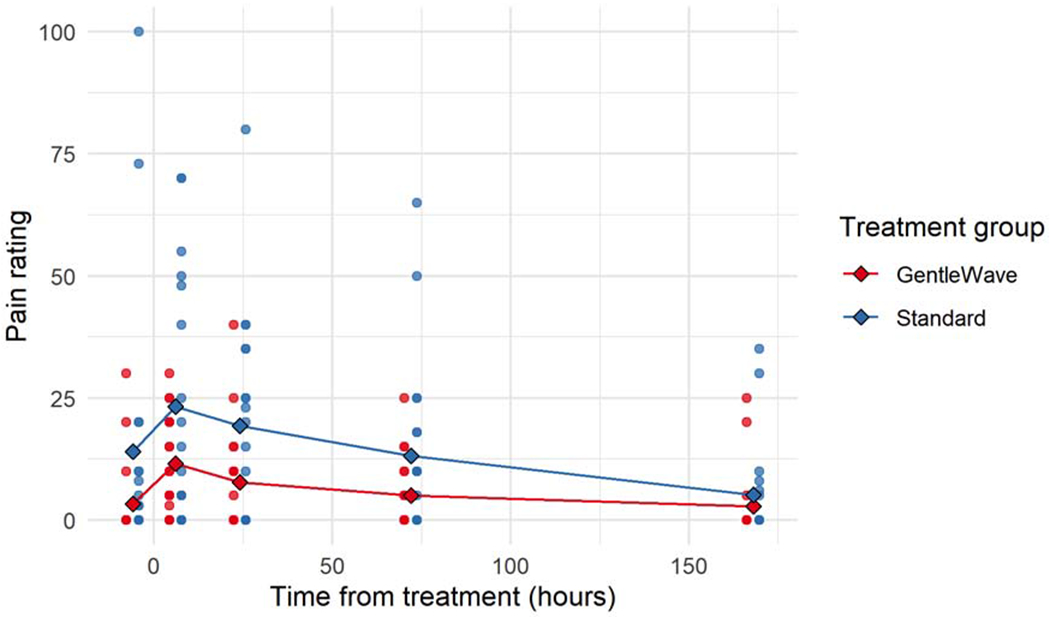

There was no significant difference found with the incidence or intensity of pain when comparing the two treatments. 72.2% (13/18) of standard treatment patients reported at least one occurrence of postoperative pain, whereas 83.3% (15/18) of GWS patients experienced at least one occurrence of postoperative pain. The greatest incidence of pain was at the six-hour post-treatment timepoint for both groups, with reports of pain decreasing in both groups as the week progressed. As shown in Figure 1, a greater level of postoperative pain was reported with the standard treatment group, however this difference was not statistically significant and both pain intensity medians were in the low – mild pain range. The median pain levels reported at the 1 -week timepoint were low (See Table 2). Additionally, pain intensity significantly decreased as time progressed from the six-hour post-treatment timepoint (p < 0.000000124).

Figure 1:

Pain intensity scores before and after treatment

Table 2:

Median (IQR) pain rating for each of the 5 measured timepoints and the p-value of a Wilcoxon rank sum (Mann-Whitney) test comparing the medians of the two groups.

| GentleWave | Standard | All | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 18 | 18 | 36 | |

| Pain 6 hours pretreatment | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 3.00 (0.00, 10.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 8.50) | 0.034 |

| Pain 6 hours post-treatment | 10.00 (3.50, 20.00) | 12.50 (1.25, 46.00) | 10.00 (2.25, 25.00) | 0.433 |

| Pain 24 hours post-treatment | 2.50 (0.00, 10.00) | 17.50 (0.00, 32.50) | 10.00 (0.00, 23.50) | 0.111 |

| Pain 72 hours post-treatment | 0.00 (0.00, 8.75) | 7.50 (0.00, 18.00) | 2.50 (0.00, 11.25) | 0.222 |

| Pain 168 hours post-treatment | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 5.75 | 0.00 (0.00, 1.25) | 0.261 |

Only four patients reported the need for postoperative rescue analgesics. For the standard treatment group, one patient reported taking 600 mg ibuprofen with 1000 mg acetaminophen every six hours for two days following treatment. For the GWS group, one patient reported taking one dose of 600 mg ibuprofen in the 24 hours following treatment. One patient took 600 mg ibuprofen every six hours for 24 hours following treatment and the last patient took one 600 mg dose of ibuprofen immediately following treatment and a second dose six hours after that.

DISCUSSION

This study attempted to determine whether there was a significant difference in the incidence or intensity of postoperative pain following treatment with the GWS versus standard endodontic treatment. The results show there is no statistically significant difference in the incidence or intensity of postoperative pain between the two treatment groups. Out of the 36 patients who returned their pain surveys, 28 reported at least one instance of discomfort following their root canal procedure, for an overall incidence of 77.8%. A majority of postoperative pain recordings were made at the six-hour and 24-hour timepoints. Previous studies have found that following root canal treatment using the GWS, patients have experienced very little postoperative pain, with Sigurdsson et al 2018, finding that only 15.6% of patients experienced ‘mild’ postoperative discomfort up to 2 days following treatment (8). This was similar to the results found by Harrison et al 1983 when looking at interappointment and postoperative pain following standard root canal treatment (12, 13). There are several factors that can cause postoperative discomfort, including local anesthetic choice and technique, the administration of pre- or post-treatment analgesics, irrigant extrusion, over-instrumentation, extended periods of mouth opening, or even referred pain. Within this study, no long-acting anesthetic or analgesics were administered and there was no difference between the occurrence of postoperative pain with several factors including age, tooth type, number of appointments, rotary file system, master apical prep size, type of sealer used, or obturation technique. Postoperative instructions typically set an expectation of the discomfort that can occur following treatment, which can ultimately affect a patient’s response to pain and influence whether or not that discomfort is reported. Also, if the postoperative pain is less intense than what was experienced pre-operatively, patients may feel inclined not to report that pain either. However, separate studies by Eriksson et al 2014 and Talib et al 2018, have found that patients see a benefit in symptom questionnaires if there is a genuine interest displayed by the healthcare professional in using the information gathered to improve treatment (14, 15). This factor, or the instruction to specifically pay attention to their state of pain, may have resulted in a higher amount of pain reports than what has been seen in previous postoperative pain studies (9).

The standard pain assessment generally seeks the intensity of pain, because it is easy to declare and is easy to measure by several different methods (16). Although the visual analog scale (VAS) is one of the most widely used tools to survey the severity and relief of pain, the NRS is regarded as one of the best single-item methods available to estimate the intensity of pain (17, 18). The NRS is the preferred method of pain analysis by patients because it simplifies how to describe their pain (19). The results of this study show there is no significant difference in the level or intensity of postoperative pain when comparing a standard endodontic treatment with treatment using the GWS. The highest level of postoperative pain reported for the GWS was ‘40’ which is considered moderate pain, and the highest level reported for standard treatment was ‘80’ which is severe. The median pain levels for both treatment groups were low to mild at all timepoints and most individual pain states peaked at 6 - 24 hours following treatment. When evaluating pain intensity, determining the survey cut-off points of pain descriptors can be important for interpreting data. Sigurdsson et al 2018, used a 10 cm VAS and selected the cut-off points of 6 cm and 8 cm as the upper limits of mild and moderate pain, respectively (8). However, other studies have found that lower cut-off points for mild and moderate pain are better for more accurately categorizing pain intensity. Boonstra et al 2014, found the cut-off points of 3.4 cm and 7.4 cm, on a 10 cm VAS, to be optimal for categorizing mild and moderate pain (20), and Aun et al 1986, found the cut-off points of 4.4 cm and 7.4 cm to be most accurate (21). This study’s 0-100 NRS pain assessment used the cut-off points of 39 and 79 for mild and moderate pain, respectively, corresponding with Hirschfield and Zernikov 2013, who found 4 & 8 on a 0-10 NRS to be optimal cut-off points for mild and moderate pain (22). The pain assessment used in this study also included a Wong-Baker FACES to help patients further determine their level of pain at each timepoint.

Farrar et al 2001, found that a 20% change in pain on an NRS between any two time points is clinically significant (23). This study found that 33.3% of each treatment group experienced a clinically significant increase in pain between pre- and post-treatment. Each group also experienced a statistically significant decrease in pain intensity as time progressed following the six-hour post-treatment timepoint.

The low sample size is a possible limitation of this study. Although the sample size collected was enough to generate significant power statistically, a greater number of participants could have elicited some statistically significant data differentiating the two treatment modalities. The Institutional Review Board restricted the recruitment size to 50 patients, this could have been due to the novel nature of the GWS or due to the lack of previous literature studying postoperative pain with the system. Even though the GWS is FDA cleared, its mechanism of action is nothing like any other method of irrigant delivery currently available. The device delivers a constant stream of irrigants, between 275 and 350 ml per 7-8 minute procedure. Conversely, conventional needle irrigation under direct operator control, intermittently delivers a considerably smaller amount of irrigant over the entire treatment period. Although standard irrigation delivers a lower volume of solution, the irrigant concentration is typically higher which is more effective at dissolving necrotic tissue (24). Additionally, 10 ml of intraoperative NaOCl is sufficient to remove superficial debris and the smear layer (25). Favorably, there were no NaOCl accidents or procedural errors with either treatment group, which could have negatively affected the outcome.

Future studies should focus on recruiting more participants and making all treatments either single or multi-visit. With most of the pain eliminated between appointments, this caused a majority of two-appointment patients to have a pre-treatment pain rating of ‘zero’. Due to randomization, a greater number of these two-appointment treatments were GWS cases, which caused the difference in pre-treatment pain between the two treatment arms to be statistically significant. Additionally, future studies should narrow the inclusion criteria (e.g. only irreversible pulpitis or necrotic pulp) and standardize more variables (e.g. master apical size or sealer type) in order to reduce confounding factors.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that:

1) Following treatment using the GWS, there was no significant difference in the incidence or intensity of postoperative pain compared to a standard endodontic treatment using a conventional side-vented needle and ultrasonic activation.

2) There was a statistically significant decrease in pain intensity as time increased following both the standard and GWS treatments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors deny any conflicts of interest related to this study.

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1-TR002494. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The research was supported in part by the American Association of Endodontists Foundation for Endodontics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peters OA, Peters CI, Basrani B. Cleaning and shaping the root canal system In: Hargreaves KM, Berman LH, eds. Cohen’s Pathways of the pulp. 11thed. St. Louis: Mosby, Inc., 2016:209–279. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang R, Shen Y, Ma J, Huang D, Zhou X, Gao Y, Haapasalo M. Evaluation of the effect of needle position on irritant flow in the C-shaped root canal using a computational fluid dynamics model. J Endod 2015; 41: 931–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandrangi P, Basrani B. Multisonic ultracleaning in molars with the GentleWave system. Oral Health. 2015;72–8626123713 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jayakodi H, Kailasam S, Kumaravadivel K, Thangavelu B, Mathew S. Clinical and pharmacological management of endodontic flare-up. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2012; 4(Suppl 2):S294–S298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siqueira JF, Barnett F. Interappointment pain: mechanisms, diagnosis, and treatment. Endod Topics. 2004; 7: 93–109 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charara K, Friedman S, Sherman A, Kishen A, Malkhassian G, Khakpour M, Basrani B. Assessment of Apical Extrusion during Root Canal Irrigation with the Novel GentleWave System in a Simulated Apical Environment. J Endod 2016; 42:135–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigurdsson A, Garland RW, Le KT, Woo SM. 12-month healing rates after endodontic therapy using the novel GentleWave system: A prospective multicenter clinical study. J Endod. 2016; 42: 1040–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigurdsson A, Garland RW, Le KT, Rassoulian SA . Healing of periapical lesions after endodontic treatment with the gentlewave procedure: a prospective multicenter clinical study. J Endod 2018; 44:510–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pak JG, White SN. Pain prevalence and severity before, during, and after root canal treatment: A systematic review. J Endod 2011;37:429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sathorn C, Parashos P, Messer H. The prevalence of postoperative pain and flare-up in single- and multiple-visit endodontic treatment: a systematic review. Int Endod J 2008; 41:91–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menhinick KA, Gutmann JL, Reagan JD, Taylor SE, Buschang PH. The efficacy of pain control following a nonsurgical root canal treatment using ibuprofen or a combination of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int Endod J 2004;37:531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison JW, Baumgartner JC, Svec TA. Incidence of pain associated with clinical factors during and after root canal therapy. Part I. Inter-appointment pain. J Endod 1983;9:384–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison JW, Baumgartner JC, Svec TA. Incidence of pain associated with clinical factors during and after root canal therapy. Part II. Post-obturation pain. J Endod 1983;9:434–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson K, Wikström L, Årestedt K, Fridlund B, Broström A. Numeric rating scale: patients’ perceptions of its use in postoperative pain assessments. Applied Nursing Research 2014; 27: 41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talib TL, DeChant P, Kean J, Monahan PO, Haggstrom DA, Stout ME, Kroenke K. A qualitative study of patients’ perceptions of the utility of patient-reported outcome measures of symptoms in primary care clinics. Qual Life Res. 2018; 27: 3157–3166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haefeli M, Effering A. Pain Assessment. Eur Spine J 2006; 15:S17–S24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM, Fisher LD (1999). Comparative reliability and validity of chronic pain intensity measures. Pain 83, 157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breivik EK, Björnsson GA, Skovlund E (2000). A comparison of pain rating scales by sampling from clinical trial data. Clin. J. Pain 16, 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: A systematic literature review. J Pain and Sym Mgmt 2011; 41(6): 1073–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boonstra AM, Schiphorst Preuper HR, Balk GA, Stewart RE. Cut-off points for mild, moderate, and severe pain on the visual analogue scale for pain in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2014; 155(12): 2545–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aun C, Lam YM, Collect B. Evaluation of the use of visual analogue scale in Chinese patients. Pain 1986; 25:215-21DeDeus QD. Frequency, location and direction of the lateral, secondary, and accessory canals. J Endod 1975;1:361–610697487 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirschfeld G, Zernikow B. Variability of “optimal” cut points for mild, moderate, severe pain: neglected problems when comparing groups. Pain. 2013; 154(1): 154–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrar JT, Young JP, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001; 94: 149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hand RE, Smith ML, Harrison JW. Analysis of the effect of dilution on the necrotic tissue property of sodium hypochlorite. J Endod 1978;4:60–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada RS, Armas A, Goldman M, Lin PS. A scanning electron microscopic comparison of a high volume final flush with several irrigating solutions: part 3. J Endod 1983;9:137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]