Abstract

During public health crises including the COVID-19 pandemic, resource scarcity and contagion risks may require health systems to shift—to some degree—from a usual clinical ethic, focused on the well-being of individual patients, to a public health ethic, focused on population health. Many triage policies exist that fall under the legal protections afforded by “crisis standards of care,” but they have key differences. We critically appraise one of the most fundamental differences among policies, namely the use of criteria to categorically exclude certain patients from eligibility for otherwise standard medical services. We examine these categorical exclusion criteria from ethical, legal, disability, and implementation perspectives. Focusing our analysis on the most common type of exclusion criteria, which are disease-specific, we conclude that optimal policies for critical care resource allocation and the use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should not use categorical exclusions. We argue that the avoidance of categorical exclusions is often practically feasible, consistent with public health norms, and mitigates discrimination against persons with disabilities.

Keywords: Allocation, coronavirus, disabilities, pandemics, rationing, triage

We are in the midst of a global pandemic unlike any experienced in the last century. Due to increases in demand for intensive care brought about by the influx of respiratory failure and shock among patients with COVID-19, many regions will have insufficient intensive care resources for all patients who might benefit from them (Ranney et al. 2020; Rosenbaum 2020). As a result, health systems may need to shift from a usual clinical ethic, which focuses on the well-being of individual patients, to a public health ethic which focuses on population health, (Emanuel et al. 2020; Truog et al. 2020; White and Lo 2020) under the legal protections afforded by “crisis standards of care” (Committee on Guidance for Establishing Crisis Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations; Institute of Medicine 2012).

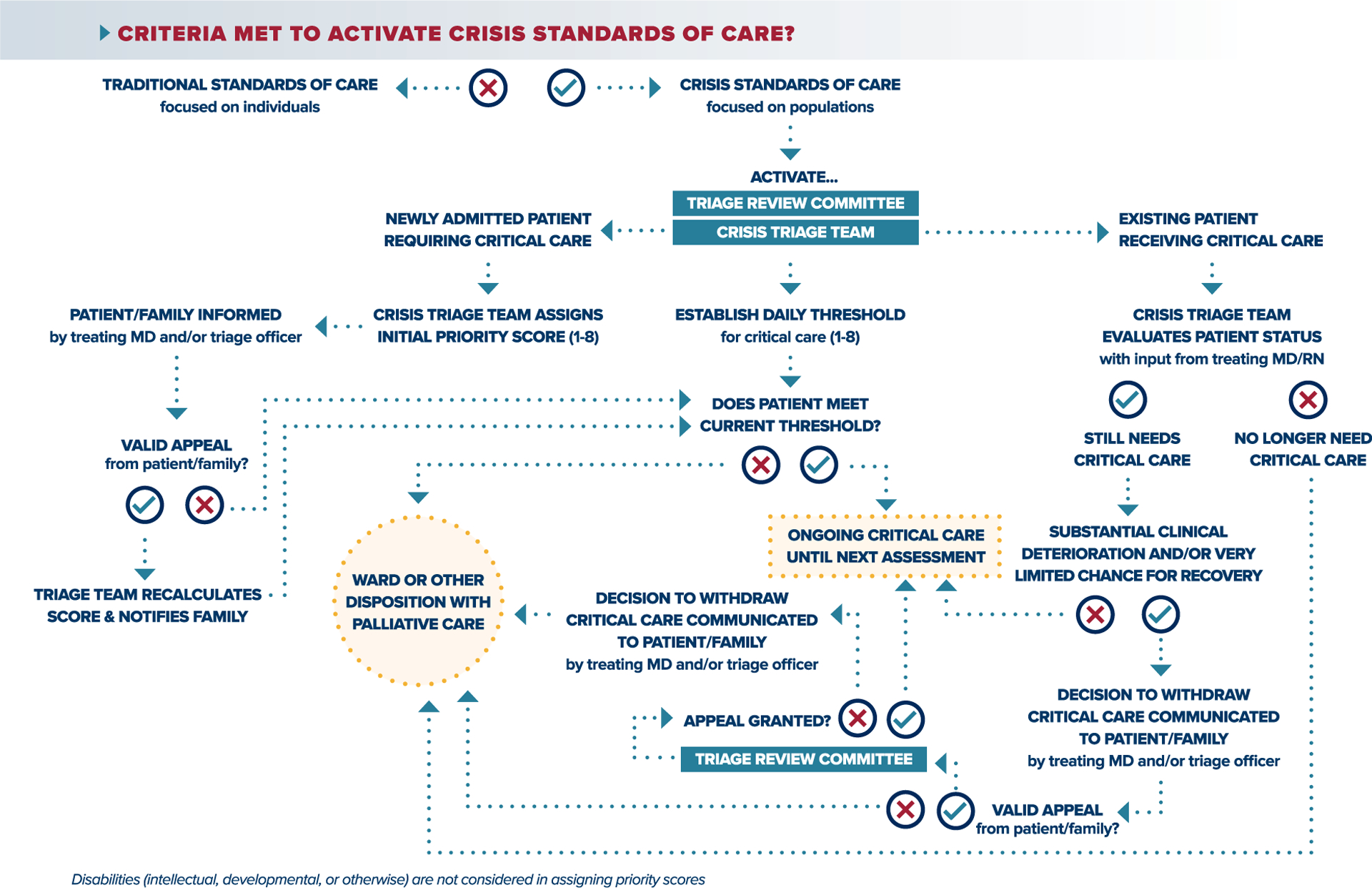

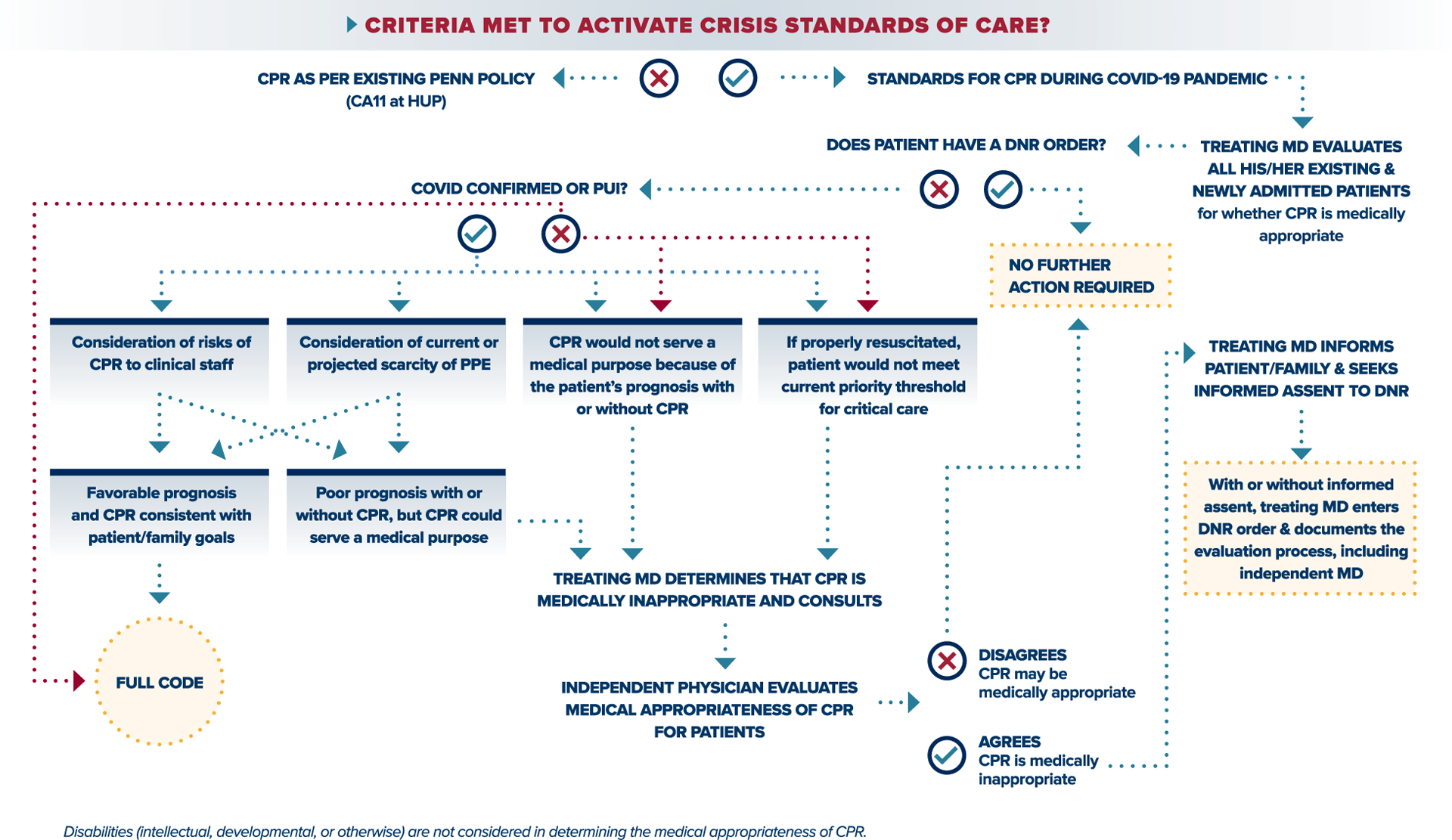

Among several key differences in existing crisis care policies, perhaps the starkest is the distinction between frameworks that do or do not begin by categorically excluding certain types of patients from consideration for health care services that would be provided under a usual standard of care. Some policies begin by excluding groups of patients (e.g., by age or comorbid disease), and then subsequently prioritize remaining patients according to chances of survival to hospital discharge and beyond (Christian et al. 2014; Pandemic Influenza Technical Advisory Committee and Florida Department of Health 2011; Tennessee Altered Standards of Care Workgroup 2016; Vergano et al. 2020). Other policies keep all patients eligible for critical care services who would qualify under normal standards of care and then allocate resources according to priority scores (White and Lo 2020). The resource allocation plan and guidance for offering cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) during crisis standards of care developed and publicly disseminated by White and Halpern (Halpern 2020b; White 2020) use this second approach (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Crisis standards of care Triage Framework.

Figure 2.

Crisis standards of care CPR Guidance.

Three central aspects of our preferred policies distinguish them from others. First, the priority scores used to guide allocation were designed with consideration of several distinct ethical values (White and Lo 2020). Rather than solely maximizing the number of survivors to hospital discharge or the greatest number of overall life-years saved, the critical care triage scoring system strives to allocate resources in light of both the immediate-term probability of surviving the critical illness and likely survival in the near-term (e.g., within 5 years). Second, the allocation framework incorporates the ethical goals of ensuring individualized patient assessments, giving some priority to essential workers, and affirmatively diminishing the negative effects of social inequalities that lessen some patients’ long-term life expectancy. The latter goal is accomplished by disregarding patients’ long-term life expectancy, such that a patient with a life expectancy of 5 years (e.g., someone with life-limiting chronic conditions that arose from social inequities) would be treated the same as a patient with a life expectancy of 25 years.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, neither the triage policy nor CPR guidance excludes any categories of patients from access to services. Instead, in the case of the allocation policy, a designated triage team calculates priority scores for all patients who meet usual indications for intensive care, such that available supply determines how many eligible patients will receive critical care at any given time. And in the case of the CPR guidance, there is no blanket exclusion from CPR for patients with COVID-19 or any other condition or characteristic. Rather, tailored decision making is preserved for all individual patients, just with a broader set of considerations regarding the medical appropriateness of CPR than routinely enter into such decisions. The absence of categorical exclusions and requiring individualized assessments of all patients are key reasons this policy, in its current form, has been approved by the Office of Civil Rights (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services 2020b).

While exclusion criteria could be designed around estimates of prognosis (such as excluding all patients with less than a year to live), most published frameworks for allocating scarce medical resources utilize disease-specific categorical exclusion criteria. For example, the 2014 CHEST Consensus Statement suggests using a list of exclusion criteria to identify patients who will not be eligible for ICU admission, such as a poor outcome prediction score, metastatic malignancy, or extreme age, (Christian et al. 2014). Similar guidelines, based largely on the CHEST Consensus Statement, have been adopted by several US states, including Tennessee and Florida (Pandemic Influenza Technical Advisory Committee and Florida Department of Health 2011; Tennessee Altered Standards of Care Workgroup 2016). A triage protocol for critical care developed in Canada to anticipate outbreaks of avian influenza also applies a similar set of exclusion criteria (Christian et al. 2006). As of February 2020, Alabama’s triage criteria for mechanical ventilators excluded patients with “severe mental retardation.” Following a complaint to the HHS Office of Civil Rights, updated guidelines were released that omit their proposed allocation framework entirely (Alabama Crisis Standards of Care Guidelines 2020; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services 2020a). More recently in Italy, a set of recommendations released by the Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Intensive Care (SIAARTI) suggested that age limits would need to be set for admission to the ICU (Vergano et al. 2020). Similar age-based exclusions have been suggested recently in the United States (Miller 2020).

In this paper, we provide a critical appraisal of incorporating categorical exclusion criteria into triage policies from the ethical and social, legal, disability, and implementation perspectives. We focus our analysis on the most common type of exclusion criteria, which are disease-specific. We conclude that optimal critical care resource allocation and CPR practice can and should be achieved without applying categorical exclusions.

ETHICAL AND SOCIAL PERSPECTIVE

The core tenets of medical ethics are generally used to describe a physician’s responsibility to individual patients (Beauchamp and Childress 1994). However, physicians’ duties have never been entirely confined to their individual patients (Chiong 2007; Halpern 2020a), and public health emergencies demand a more substantial shift toward prioritizing the well-being of populations (Thomas et al. 2002).

As the epidemiology of COVID-19 makes clear, more severe disease presentations and higher mortality rates occur in patients who are older and have greater baseline comorbid illnesses (Guan et al. 2020), including disproportionate representation in this latter group among racial and ethnic minorities (Yancy 2020). Because these patients may have limited survival, triage decisions during extreme surge periods might be similar with or without the use of categorical exclusion criteria. Indeed, we plan to evaluate the degree to which this might occur using data acquired during the current pandemic.

While awaiting such evidence, we should use the approach that is most procedurally fair (Vong 2018). Procedural accounts of justice focus on the fairness of the process of decision making, not on the outcome itself (Resnik et al. 2018). From a procedural standpoint, policies that categorically rule out groups of patients tend to be less fair than those that do not. Categorical exclusions violate the public health norms of using the least restrictive policy possible to achieve a fundamental goal, may introduce new disparities based on disease type, and potentially exacerbate existing social inequities. Implementing policies perceived as unfair could result in important social consequences.

Excessive Restriction

A fundamental principle of public health ethics is to utilize the means that are the least restrictive to accomplish the public health objective (Allen and Selgelid 2017; Childress et al. 2002). Categorical exclusions would violate this principle if alternative approaches exist. Indeed, several states, including California, Colorado, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania, have concluded that an approach to triage without using categorical exclusions is feasible, and have adopted our framework into guidelines. The American College of CHEST Physicians has arrived at the same conclusion, and a revision of the 2014 guidelines that will no longer include categorical exclusions is currently in press (American College of CHEST Physicians 2020). In the context of an infectious pandemic, there are regional and time-variant surges and declines (Prem et al. 2020). While improved regional infrastructure that facilitated and paid for transfers of patients or resources from institutions at peaks to those with capacity could prevent the need for triage at all, in the meantime policies that avoid categorical exclusions provide a less restrictive solution to the problem because they provide flexibility to vary eligibility thresholds for who will receive services as capacity changes.

Failure to Protect Patients with Special Needs or Social Disadvantages

One central goal for any framework to ration health-care resources in the setting of a public health emergency should be to maximize benefits derived from those scarce resources (Elpern et al. 2005; Emanuel et al. 2020; Truog et al. 2020; White and Lo 2020). This sentiment is often presented in two ways: maximizing the number of lives saved, or maximizing the number of life-years saved (Emanuel et al. 2020). There are concerns that efforts to promote pure maximization using simple categorical exclusions might disadvantage certain groups of people, such as the elderly or those with disabilities.

Our advocated allocation framework does not adopt a pure “maximizing” approach. Instead, the system for assigning priority scores is an effort to incorporate several distinct and widely accepted ethical values about allocating scarce resources, several of which constrain simple maximization. For example, younger age is only considered as a tie-breaking criterion for allocation, rather than a form of explicit prioritization, even though prioritizing younger age would tend to maximize life-years gained. Similarly, our advocated approach to CPR does not categorically exclude specific groups of patients, such as patients with COVID-19 who suffer in-hospital asystolic arrests, even though doing so would likely maximize outcomes for all patients by preserving personal protective equipment and the clinical workforce. These policies thereby ensure meaningful access to care for all patients, and more equitably distribute at least some benefits for the greatest number of people.

Introduction of Age and Disease-Specific Disparities

Policies utilizing categorical exclusions typically list age cutoffs, disease conditions, or comorbidities that portend limited life-expectancies. In doing so, they may introduce disease-specific disparities, by inadvertently excluding some diseases but not others with similar prognoses. No list of chronic diseases could be fully predictive, exhaustive, or guaranteed to generate equal weighting of similarly mortal conditions. Thus, the use of exclusion criteria could lead to certain patients being definitively excluded simply because we have, or think we have, better actuarial evidence about their diseases than we do about others. Age is one of the simplest forms of categorical exclusions. Restricting care from the elderly is based on the assumption that they are unlikely to benefit from ICU care. However, older patients with a few chronic health conditions will often have better outcomes than younger patients with multiple comorbidities. Thus, no specific age threshold, nor a finite list of disease conditions, can be exhaustive of all correspondingly poor prognostic criteria, nor assured of leading to optimal outcomes.

Exacerbation of Existing Social Inequities

While no policy we have reviewed incorporates exclusion criteria based on race, ethnicity, or income, it is still possible that policies with disease-specific categorical exclusion criteria will harm persons from disadvantaged backgrounds. As we begin to see the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 in minority communities (Martin et al. 2020; The Associated Press 2020), there is a growing concern that this disease will itself intensify long-standing racial and economic disparities. Decreased access to care may delay presentations to medical care, and higher rates of comorbidities may also cause greater acuity upon presentation. No system that aspires toward saving lives and life-years can fully obviate the possibility that poor and minority patients will garner lower priority scores due to disease conditions known to be driven by established social inequities. And any policies that rely, even in part, on physician judgment are vulnerable to the influence of unconscious bias. However, approaches that systematically exclude from critical care patients with diseases that arise disproportionately in disadvantaged groups may explicitly worsen such disparities. And states such as Pennsylvania have wisely sought to limit the influence of unconscious bias by requiring training in it among triage officers.

Social and Psychological Consequences of Policies Deemed Unjust

Categorical exclusion criteria that are perceived as unjust could potentially harm society in a variety of ways. Such criteria may be interpreted as devaluing certain types of lives. Such impressions can weaken public trust and result in devastating consequences for the public health response to a pandemic as well as to future clinician-patient relationships. Effective public health response to a pandemic requires a high degree of public confidence and cooperation (Siegrist and Zingg 2014). Any public health initiative that degrades that trust has the risk of not only being ineffective, but of impeding implementation of initiatives such as social distancing and self-quarantine, the burdens of which are felt disproportionately by people living in poverty. Moreover, it increases the risk that society may emerge from the pandemic more divided along racial, disability, and class lines than it was before.

Even in normal times, a lack of trust in clinicians has been associated with inferior health outcomes (Birkhäuer et al. 2017). If an allocation policy implemented by medical professionals is perceived as unfair, it could generate further distrust, and negatively impact public health even beyond the response to the pandemic.

The public’s sense of a policy’s fairness is not the only critical perspective. If clinicians themselves feel that triage or CPR policies are unfairly excluding patients from care, the psychological burden could be substantial. We already know that front-line health care workers engaged in the care of patients with COVID-19 are at higher risk of adverse mental health outcomes (Lai et al. 2020), and there have been numerous reports of the anguish faced by Italian physicians in having to make rationing decisions without clear guidance (Ferraresi 2020; Shurkin 2020). One goal of implementing a triage policy is to obviate the need for bedside clinicians to make such devastating decisions without guidance. However, if that policy is perceived as unfair by those very clinicians, it may cause more psychological harm than good.

LEGAL PERSPECTIVE

Categorical exclusions based on quality of life judgments would conflict with both recent and older guidance from the Department of Health and Human Services (Gale Academic OneFile 1994; HHS Office for Civil Rights in Action 2020), although this guidance has not been directly tested in court. The legality of categorical exclusions that are explicitly not based on quality-of-life considerations is more complex. For conditions with highly variable effects on overall survival and even short-term life expectancy, such as breast cancer, categorical exclusions may violate both guidance and case law requiring that clinical judgments be individualized (HHS Office for Civil Rights in Action 2020; Lesley v. Hee Man Chie 2001; Sumes v. Andres 1996). One case, for instance, upheld a medical decision “made pursuant to an individualized inquiry” that “was confirmed by independent, knowledgeable persons at the time,” and contrasted it with decisions that “rested on stereotypes of the disabled rather than an individualized inquiry into the patient’s condition” (Lesley v. Hee Man Chie 2001). In contrast, categorical exclusions are more legally defensible for illnesses that consistently limit short-term life expectancy (Wolf and Hensel 2011). Examples might include certain metastatic or high-grade cancers. However, exclusions are most secure legally when they include all diseases that are equally life-limiting, which may prove impossible due to limitations in the availability of valid prediction models.

DISABILITY PERSPECTIVE

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that one in four adults in America has disabilities (Okoro et al. 2018). Disability is a part of the human experience, but disability is disproportionately experienced by individuals living in or near poverty, minorities, those with lower educational attainment and individuals living in rural areas (Campbell et al. 2009; National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine 2018; Zhao et al. 2019). Stigma and inaccurate assumptions about the quality of life achievable when people have disabilities are incredibly pervasive in our society (National Council on Disability 2019; Wasserman et al. 2016). Even when purportedly “objective” criteria are employed to allocate health care resources, subjective notions of the quality or desirability of life with disabilities may play an influential role. These negative biases and assumptions often result in the devaluing of the lives of people with disabilities which contributes to health care inequities and discrimination in multiple sectors of society. Medical providers, especially those who adhere to the medical model of disability and who do not understand the lived experiences of people with disabilities, are not immune to biases against people with disabilities (Fitzgerald and Hurst 2017). These biases and existing barriers to care instill a sense of distrust in medical professionals within the disability community. A scarce resource allocation framework that categorically excludes persons with disabilities would formalize these biases into a deadly form of discrimination and further disenfranchise people with disabilities (Albrecht et al. 2001; Hanschke et al. 2015).

When considering the allocation of scarce resources, it is important to frame the discussion in terms of human rights—the set of protections and entitlements afforded to all people, including those with disabilities. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities includes the provision that nations should provide equal access to health care and other related services for people with disabilities (Stein et al. 2009). The preclusion of disability as a factor in denying health care, or providing discriminatory or substandard health care, as detailed in Article 25 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons, should extend to situations of scarcity, mandating that individuals with disabilities receive comparable treatment to individuals without disabilities (Hanschke et al. 2015). From the Disability Rights perspective, the core principles of dignity, nondiscrimination, equality of opportunity, and accessibility should be central considerations during resource allocation planning in viral pandemics. Further, the inclusion of the disability community in resource allocation planning should be fostered (Hanschke et al. 2015).

IMPLEMENTATION PERSPECTIVE

It is essential to anticipate and evaluate the effective implementation of policies to allocate limited resources and govern the use of CPR during emergencies. Any policy, no matter how deliberately and thoughtfully designed, will be ineffective if it cannot be implemented in a consistent and efficient manner. A potential advantage of policies that apply categorical exclusions may be ease of implementation. Categorical exclusions that can be found in a list (however imperfect) may be simpler to disseminate, comprehend, and execute than the alternative of calculating priority scores for all-comers and allocating resources based on dynamic changes in availability. This is particularly true in the emergency department, where treatment decisions may need to be made before the data required for prioritization are available. Additionally, whereas errors could be made in calculating priority scores, fixed lists of exclusion criteria have the appeal of simplicity and consistency (Wolf and Hensel 2011).

The implementation of prioritization schemes may also require more resources to implement than policies that rely only on inclusions versus exclusions. Prioritization frameworks require the creation of triage teams (which may divert scarce clinicians from frontline clinician pools), frequent assessments of bed and other resource availability, and the development of electronic-health-record features that facilitate fair and consistent data capture and evaluation. If triage teams evaluate patients at the bedside, the protocol may also result in increased utilization of personal protective equipment as well as increased risk of disease transmission to health care workers. Any of these unintended consequences might detract from the central goal of producing the best possible outcomes for the population as a whole.

However, nearly all allocation frameworks that utilize categorical exclusion criteria also include guidance on prioritizing the patients that remain after the application of exclusions. If the needs for critical care resources exceed the availability after excluding some patients, a more complex prioritization scheme will still be required. To be prepared for such an event, an institution would need to have a triage team available, thus limiting the efficiencies to be gained by incorporating exclusion criteria.

CONCLUSIONS

COVID-19 has caused transitions to crisis standards of care in certain parts of the world and continues to threaten to do so elsewhere. We have described the advantages and disadvantages of incorporating categorical exclusion criteria into allocation policies for critical care triage and decisions on CPR. We conclude that consistent with the public health norms of using the least restrictive policy possible to achieve a fundamental goal and avoiding discrimination against persons with disabilities, optimal critical care resource allocation and CPR practices can and should be achieved without using categorical exclusions.

Though there are valid concerns about the feasibility of such policies from an implementation standpoint, the operational virtues of categorical exclusions are largely realized only in binary systems in which patients are either deemed eligible or ineligible without any further prioritization among the eligibles. And in any case, the feasibility virtues offered by such coarse systems are readily outweighed by their threats to justice, public trust, and clinician morale. Although no policy can ever perfectly accommodate the many considerations inherent in these tragic choices, transparent and consistent implementation during COVID-19, coupled with ongoing evaluation, refinement, and community engagement, will enable us to be better prepared for the next disaster.

REFERENCES

- Alabama Crisis Standards of Care Guidelines. 2020. Managing modified care protocols and the allocation of scarce medical resources during a healthcare emergency. https://www.adph.org/CEPSecure/assets/alabamacscguide-lines2020.pdf (accessed April 13, 2020).

- Albrecht GL, Seelman KD, and Bury M. 2001. Handbook of disability studies. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; https://www.worldcat.org/title/handbook-of-disability-studies/oclc/45363220. [Google Scholar]

- Allen T, and Selgelid MJ. 2017. Necessity and least infringement conditions in public health ethics. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 20(4): 525–535. doi: 10.1007/s11019-017-9775-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of CHEST Physicians 2020. Triage of scarce critical care resources in COVID-19: An implementation guide for regional allocation: An expert panel report of the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and the American College of Chest Physicians. Northbrook, IL: ACCP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp TL, and Childress JF. 1994. Principles of medical ethics. 4th ed New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Birkhäuer J, Gaab J, Kossowsky J, et al. 2017. Trust in the health care professional and health outcome: A meta-analysis. PLoS One 12(2): e0170988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell VA, Gilyard JA, Sinclair L, Sternberg T, and Kailes JI. 2009. Preparing for and responding to pandemic influenza: Implications for people with disabilities. American Journal of Public Health 99(S2): S294–S300. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress JF, Faden RR, Gaare RD, et al. 2002. Public health ethics: Mapping the terrain. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 30(2): 170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2002.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiong W 2007. Justifying patient risks associated with medical education. Journal of the American Medical Association 298(9): 1046–1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.9.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian MD, Hawryluck L, Wax RS, et al. 2006. Development of a Triage Protocol for critical care during an influenza pandemic. Canadian Medical Association Journal 175(11): 1377–1381. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian MD, Sprung CL, King MA, et al. 2014. Triage: Care of the critically ill and injured during pandemics and disasters: CHEST consensus statement. Chest 146(4): e61S–e74S. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Guidance for Establishing Crisis Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations; Institute of Medicine 2012. Crisis standards of care: A systems framework for catastrophic disaster response. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24830057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elpern EH, Covert B, and Kleinpell R. 2005. Moral distress of staff nurses in a medical intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care 14(6): 523–530. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2005.14.6.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. 2020. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraresi M 2020. A coronavirus cautionary tale from Italy: “Don’t Do What We Did.” The Boston Globe, March 13. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/03/13/opinion/corona-virus-cautionary-tale-italy-dont-do-what-we-did/

- Fitzgerald C, and Hurst S. 2017. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics 18(1): 19. doi: 10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale Academic OneFile. 1994. ADA analyses of the Oregon Health Care Plan. Issues in Law & Medicine. https://link-gale-com.proxy.library.upenn.edu/apps/doc/A15169193/AONE?u=upenn_main&sid=AONE&xid=6e01325e (accessed April 17, 2020). [PubMed]

- Guan W-j, Z-y Ni, Hu Y, et al. 2020. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New England Journal of Medicine 382(18): 1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern SD 2020a. First-come, first-served healthcare no longer applies. We must now allocate care to those who will benefit the most. Newsweek, March 4. https://www.newsweek.com/first-come-first-served-healthcare-allocating-benefit-most-1496009.

- Halpern SD 2020b. Guidance for decisions regarding cardopulmonary resuscitation during the COVID19 pandemic. http://pair.upenn.edu/covid-19-resources (accessed April 13, 2020).

- Hanschke K, Wolf LE, and Hensel WF. 2015. The impact of disability: A comparative approach to medical resource allocation in public health emergencies. Saint Louis University Journal of Health Law & Policy 8: 259–314. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/02/world/africa/african-leaders-and-who-intensify-effort-to- [Google Scholar]

- HHS Office for Civil Rights in Action. 2020. Bulletin: Civil Rights, HIPAA, and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/related-stigma.html (accessed April 16, 2020).

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. 2020. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Network Open 3(3): e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesley v. Hee Man Chie, 250 F.3d 47, 55 (1st Cir. 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Fernandez A, and Bibbins-Domingo K. 2020. Who lies beneath the flattened curve: LatinX and COVID-19.” The San Francisco Examiner, April 9. https://www.sfexaminer.com/opinion/who-lies-beneath-the-flattened-curve-latinx-and-covid-19/.

- Miller FG 2020. Why I Support Age-Related Rationing of Ventilators for Covid-19 Patients. The Hastings Center. https://www.thehastingscenter.org/why-i-support-age-related-rationing-of-ventilators-for-covid-19-patients/ (accessed April 16, 2020).

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine 2018. People Living with Disabilities: Health Equity, Health Disparities, and Health Literacy. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Disability 2019. Medical futility and disability bias. Washington DC: NCD; www.ncd.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Okoro CA, Hollis ND, Cyrus AC, and Griffin-Blake S. 2018. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults — United States, 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67(32): 882–887. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandemic Influenza Technical Advisory Committee and Florida Department of Health. 2011. Pandemic influenza: Triage and scarce resource allocation guidelines. https://bioethics.miami.edu/_assets/pdf/about-us/special-projects/ACS-GUIDE.pdf (accessed April 10, 2020).

- Prem K, Liu Y, Russell TW, et al. 2020. The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: A modelling study The Lancet Public Health. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30073-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranney ML, Griffeth V, and Jha AK. 2020. Critical supply shortages — The need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine 382(18): e41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2006141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnik DB, MacDougall DR, and Smith EM. 2018. Ethical dilemmas in protecting susceptible subpopulations from environmental health risks: Liberty, utility, fairness, and accountability for reasonableness. The American Journal of Bioethics 18(3): 29–41. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2017.1418922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum L 2020. Facing Covid-19 in Italy – ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line The New England Journal of Medicine. Advance online publication; 10.1056/NEJMp2005492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shurkin J 2020. COVID-19: The ethical anguish of rationing medical care.” Discover Magazine, April 2. https://www.discovermagazine.com/health/covid-19-the-ethical-anguish-of-rationing-medical-care

- Siegrist M, and Zingg A. 2014. The role of public trust during pandemics. European Psychologist 19: 23–32. http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1027/1016-9040/A000169 [Google Scholar]

- Stein MA, Stein PJ, Weiss D, and Lang R. 2009. Health care and the UN disability rights convention. The Lancet 374(9704): 1796–1798. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62033-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumes v. Andres, 938 F. Supp. 9, 11–12 (D.D.C. 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Tennessee Altered Standards of Care Workgroup. 2016. Guidance for the ethical allocation of scarce resources during a community-wide public health emergency as declared by the Governor of Tennessee. http://www.midsouthepc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2016_Guidance_for_the_Ethical_Allocation_of_Scarce_Resources.pdf (accessed April 10, 2020).

- The Associated Press. 2020. Outcry over racial data grows as virus slams Black Americans. The New York Times, April 8. https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2020/04/08/us/ap-us-virus-outbreak-race.html.

- Thomas JC, Sage M, Dillenberg J, and Guillory VJ. 2002. A code of ethics for public health. American Journal of Public Health 92(7): 1057–1059. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.7.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truog RD, Mitchell C, and Daley GQ. 2020. The toughest triage – Allocating ventilators in a pandemic The New England Journal of Medicine. Advance online publication; 10.1056/NEJMp2005689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2020a. OCR reaches early case resolution with Alabama after it removes discriminatory ventilator triaging guidelines. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/04/08/ocr-reaches-early-case-resolution-alabama-after-it-removes-discriminatory-ventilator-triaging.html (accessed April 13, 2020).

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2020b. OCR resolves civil rights complaint against Pennsylvania after it revises its pandemic health care triaging policies to protect against disability discrimination. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/04/16/ocr-resolves-civil-rights-complaint-against-pennsylvania-after-it-revises-its-pandemic-health-care.html (accessed April 16, 2020).

- Vergano M, Bertolini G, Giannini A, Gristina G, Livigni S, Mistraletti G, and Petrini F. 2020. Clinical ethics recommendations for the allocation of intensive care treatments in exceptional, resource-limited circumstances. Italian Society of Anesthesia, Analgeisa, Resuscitation, and Intensive Care (SIAARTI). Advance online publication. http://www.siaarti.it/SiteAssets/News/COVID19-documentiSIAARTI/SIAARTI-Covid-19-ClinicalEthicsReccomendations.pdf.

- Vong G 2018. The distinct and complementary roles of procedural and outcome-based justice in health policy. The American Journal of Bioethics 18(3): 59–60. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2017.1418936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman D, Asch A, Blustein J, and Putnam D. 2016. Disability: Health, well-being, and personal relationships. Stanford Encylopedia of Philosophy, February 18. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/disability-health/.

- White DB 2020. A model hospital policy for allocating scarce critical care resources. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh; https://ccm.pitt.edu/node/1107 [Google Scholar]

- White DB, and Lo B. 2020. A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. Advance online publication; 10.1001/jama.2020.5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf L, and Hensel W. 2011. Valuing lives: Allocating scarce medical resources during a public health emergency and the Americans with Disabilities Act (Perspective). PLoS Currents 3: RRN1271. doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy CW 2020. COVID-19 and African Americans JAMA. Advance online publication; 10.1001/jama.2020.6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Okoro CA, Hsia J, Garvin WS, and Town M. 2019. Prevalence of disability and disability types by urban–rural county classification—U.S., 2016. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 57(6): 749–756. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]