Abstract

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) infection is known to cause skin blisters, keratitis as well as deadly cases of encephalitis in some situations. Only a few therapeutic modalities are available for this globally prevalent infection. Very recently, a small molecule BX795 was identified as an inhibitor of HSV-1 protein synthesis in an ocular model of infection. In order to demonstrate its broader antiviral benefits, this study was aimed at evaluating the antiviral efficacy, mode-of-action, and toxicity of BX795 against HSV-1 infection of three human cell lines: HeLa, HEK, and HCE. Several different assays, including cell survival analysis, imaging, plaque analysis, Immunoblotting, and qRT-PCR, were performed. In all cases, BX795 demonstrated low toxicity at therapeutic concentration and showed strong antiviral benefits. Quite interestingly, cell line-dependent differences in the mechanism of antiviral action and cytokine response to infection were seen upon BX795 treatment. Taken together, our results suggest that BX795 may exert its antiviral benefits via cell-line specific mechanisms.

Keywords: Herpes simplex virus-1, Antiviral drug, BX795, HEK, HeLa, HCE

1. Introduction

Herpes Simplex virus-1(HSV-1) is a double-stranded DNA virus that is notorious for causing infectious blindness, orofacial blisters, and in rare cases, encephalitis (Yadavalli, Ames et al., 2019;Koganti et al., 2019;Costa and Sato, 2019). It is among one of the most common and equally serious human pathogens that persist for the lifetime of infected patients (Whitley and Bernard, 2001). According to the World Health Organization, 3.7 billion people under age 50 had HSV-1 infection in 2012. The prevalence of HSV-1 increases with age, and its transmission can occur via asymptomatic individuals. After primary infection at a mucosal site, the virus travels retrograde to the trigeminal ganglia to establish latency (Sun et al., 2019;Agelidis et al., 2019;Wald and Corey, 2007). Latent virions can reactivate at any time to cause health consequences, and there is no preventive vaccine or cure available against the virus (Noska et al., 2015; Kane and Golovkina, 2010).

Acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir, ganciclovir, and trifluridine (TFT) are some of the nucleoside analogs that have been in use for the treatment of HSV-1 symptoms for years. These analogs inhibit viral thymidine kinase and hence halt HSV-1 DNA replication (Azher et al., 2017;Sharma et al., 2012;Koganti et al., 2019;Jordheim et al., 2013). Although nucleoside analogs are very useful, they do suffer from significant limitations. For example, they are teratogenic and cannot be prescribed during pregnancy (Clive et al., 1983;Straface et al., 2012). Acyclovir is nephrotoxic and cannot be given to patients with renal failure(Fleischer and Johnson, 2010;Yildiz et al., 2013;Spiegal and Lau, 1986). TFT can cause ocular toxicity after prolonged use (Maudgal et al., 1983;Udell, 1985;Jayamanne et al., 1997). All these side effects of nucleoside analogs and 50–90% global prevalence of HSV-1, demands the discovery of new treatment options with safer and alternative mechanisms(Jaishankar and Shukla, 2016;Cunningham et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2016).

Recently, we serendipitously found that an off-target effect of BX795 suppresses HSV-1 growth in human corneal epithelial cells (HCEs) and blocks the development of keratitis in a murine model of infection (Jaishankar et al., 2018). However, the study was limited to demonstrate the antiviral efficacy of BX795 in corneal cells with a singular effective concentration. In this study, we demonstrate the antiviral efficacy of BX795 in multiple cell lines of human origin and show a correlation between dose response and antiviral activity. Our results discussed below demonstrate safety, antiviral efficacy, and mechanism of action of BX795 against HSV-1 infection of three different cell lines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells, Viruses, Media

HEK, HeLa, and Vero cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with P/S and 10% FBS. HCEs were passaged in MEM, also supplemented with 1% P/S and 10% FBS. The list of reagents and their sources is given in Table 1.

Table 1:

Reagents used in the study and their sources.

| REAGENTS | SOURCE |

|---|---|

| Henrietta Lacks Cells (HeLa) | B. S. Prabhakar (The University of Illinois at Chicago) |

| African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells | P. G. Spear’s laboratory at Northwestern University |

| Human Corneal Epithelial Cells (RCB1834 HCE-T) | K. Hayashi (National Eye Institute) |

| Human Embryonic Kidney Cells (HEK) | ATCC |

| HSV-1 (17 GFP) | P. G. Spear’s laboratory at Northwestern University |

| MEM | Gibco |

| OPTI MEM | Gibco |

| DMEM | Gibco |

| 1% Penicillin and streptomycin (P/S) | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 10% fetal bovine serum | FBS, Sigma-Aldrich |

| BX795 | Selleckhem |

| Anti-HSV-1 gD mouse monoclonal (Dilution - 1:1000) | Abcam |

| Anti-HSV-1 ICP-0 mouse polyclonal (Dilution - 1:1000) | |

| Anti-mouse phospho-P 70 S6 Kinase (Dilution - 1: 500) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Anti-mouse P 70 S6 Kinase (Dilution - 1: 500) | |

| Anti-Akt rabbit monoclonal (Dilution - 1:1000) | Cell Signaling Technology |

| Anti-phospho-Akt- Ser473 rabbit monoclonal (Dilution - 1:500) | |

| Anti-4E-BP1 rabbit monoclonal (Dilution - 1:1000) | |

| Anti-phospho-4E-BP1-Thr37/46 rabbit monoclonal (Dilution - 1:500) | |

| Anti-GAPDH rabbit polyclonal (Dilution - 1:1000) | Protein tech |

2.2. MTT Assay

MTT assay was performed to assess the viability of cells in the presence of BX795. HCE, HeLa, and HEK cells were seeded in 96 wells flat bottom plate at a density of 4× 104/well. Upon confluence, the cells were treated with indicated concentrations of BX795 diluted in DMEM. At 24 hours post-incubation, 10μl of MTT reagent (5mg/ml) dissolved in fresh DMEM was added to each well after removing culture medium and incubated for 3 hours till purple formazan crystals started to appear. Formazan crystals were dissolved using 100μl of acidified isopropanol (1% glacial acetic acid v/v).

The dissolved formazan crystals (80μl) were transferred to a fresh 96well plate and absorbance was recorded at 560nm by a microplate reader (Tecan GENious Pro).

2.3. Plaque Assay

Plaque assay was performed to determine the total amount of infectious virus released with and without BX795 treatment. Infectious cell pellets were suspended in 1000μl of Opti MEM and lysed using a probe sonication system for 30 seconds at 70% amplitude. Sonicated cells were serially diluted in Opti MEM and added to a confluent monolayer of Vero cells in a 24 well plate. Three hours later, 5% methylcellulose laden DMEM was overlaid on these cells and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for three days. Cells were fixed in 100% methanol for 10 minutes and stained with crystal violet to determine the extent of plaque formation. Plaques were counted, and plotted as plaque-forming units using GraphPad.

2.4. Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed to determine the action of BX795 on different cellular and viral proteins. Cells were collected using incubation with Hank’s buffer for 10 minutes and pelleted (800 g for 10 minutes) in a micro-centrifuge tube. Cell pellets were dissolved in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA, Sigma-Aldrich) and protease inhibitor (100:1) for 30 minutes on ice. The mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 g at 4°C for 20 minutes, and whole-cell protein extract (supernatant) was collected. Protein samples were denatured in β-mercaptoethanol and NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Invitrogen, NP00007) incubating them at 80°C for 10 min. The denatured proteins were quickly centrifuged, allowed to cool and loaded in equal amounts to 4 to 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, and ran for three hours at the constant speed at 70V. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane from the gel using an iBlot 2 dry transfer instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The nitrocellulose membrane was blocked for an hour in blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk, 0.1% tween 20, and 1xTris-buffer saline) at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with anti-GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) antibody, anti–HSV-1 gD, and ICP-0 mouse monoclonal antibody overnight at 4°C. Blots were washed using washing buffer (1X TBS, 0.1% tween 20) 3 times (10 minutes each) on the following day and incubated at room temperature in secondary antibody at the dilution of 1: 5000 for one hour at room temperature. Bands were visualized by the addition of Super Signal West Pico maximum sensitivity substrate (Pierce, 34080) using Image Quant LAS 4000 imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

2.5. Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

To extract cellular RNA and evaluate transcripts levels in the presence of BX795, TRIzol was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted RNA was quantified using NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). RNA from all the samples were equilibrated with molecular biology grade water (Corning, USA). The RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using manufacturer’s protocol. Fast SYBR Green Master Mix on QuantStudio 7 Flex system (Applied Biosystems) was used to perform real-time PCR with Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems).

2.6. Statistical Analysis:

GraphPad vision version 6.01 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used to analyze the data. The statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed t-test and One-way ANOVA, and a p-value of <0.05 was taken as the threshold for statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. BX795 at therapeutic concentration is well tolerated by human cell lines.

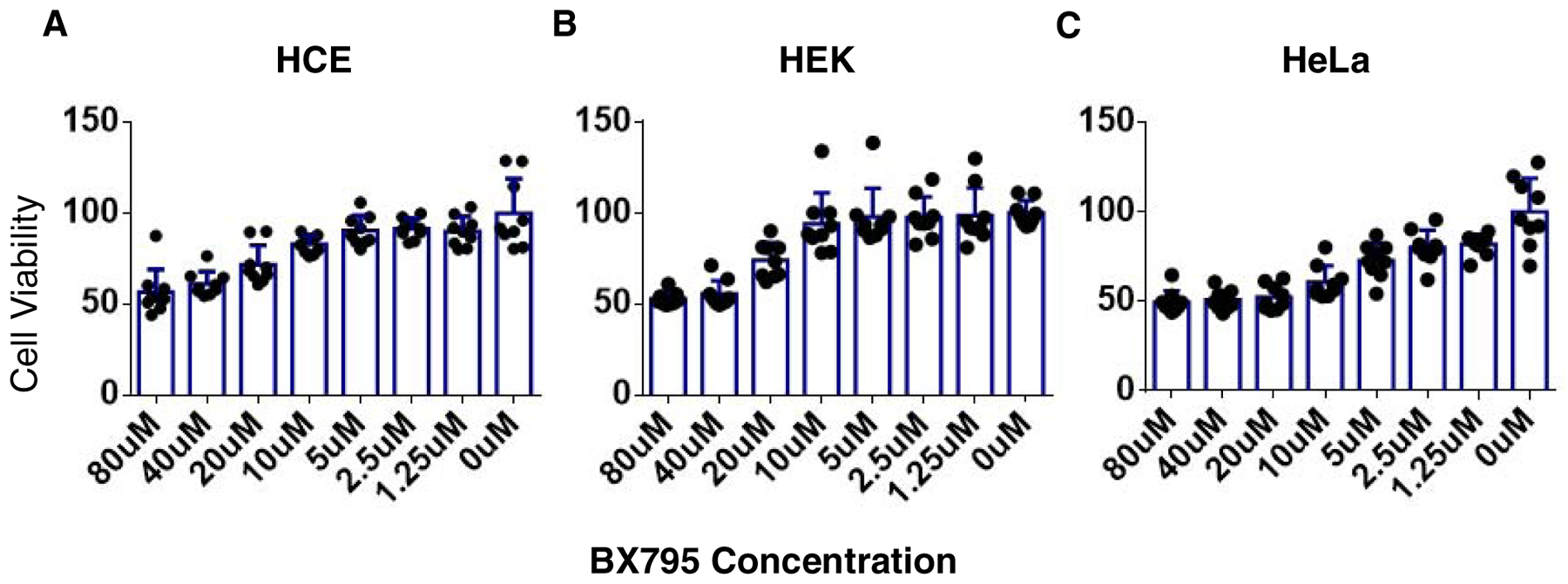

To determine any toxic effects, we assessed viability of HCE, HEK, and HeLa cell lines upon BX795 treatment. All cell lines were plated in 96 well plates and treated with increasing concentrations of BX795, ranging from 1.25μM to 80μM. Based on CC50 (cell cytotoxicity at 50%) calculations our results suggested that the therapeutic concentration of BX795 (10μM) does not adversely affect the viability of HCE, HEK, as well as HeLa (Figure. 1). Even at 40μM concentration, more than 50% of cells remained viable in all three cell lines. The 50% cytotoxic concentration of BX795 for HCE, HEK, and HeLa was found to be, 51μM, 76.5μM, and 46.35μM respectively. (Figure. 1A, B, & C).

Figure 1: The therapeutic concentration of BX795 (10μM) is well-tolerated by human cell lines.

MTT assay was performed on HeLa, HEK, and HCE cell lines to check the percentage viability in the presence of BX795. Cells were seeded in 96 wells plates at a density of 4×104 and treated with BX795 for 24hours. Percentage viability A) HCE. B) HEK. C) HeLa at different concentrations of BX795.

3.2. BX795 demonstrates broad spectrum inhibition of HSV-1 infection in human cell lines.

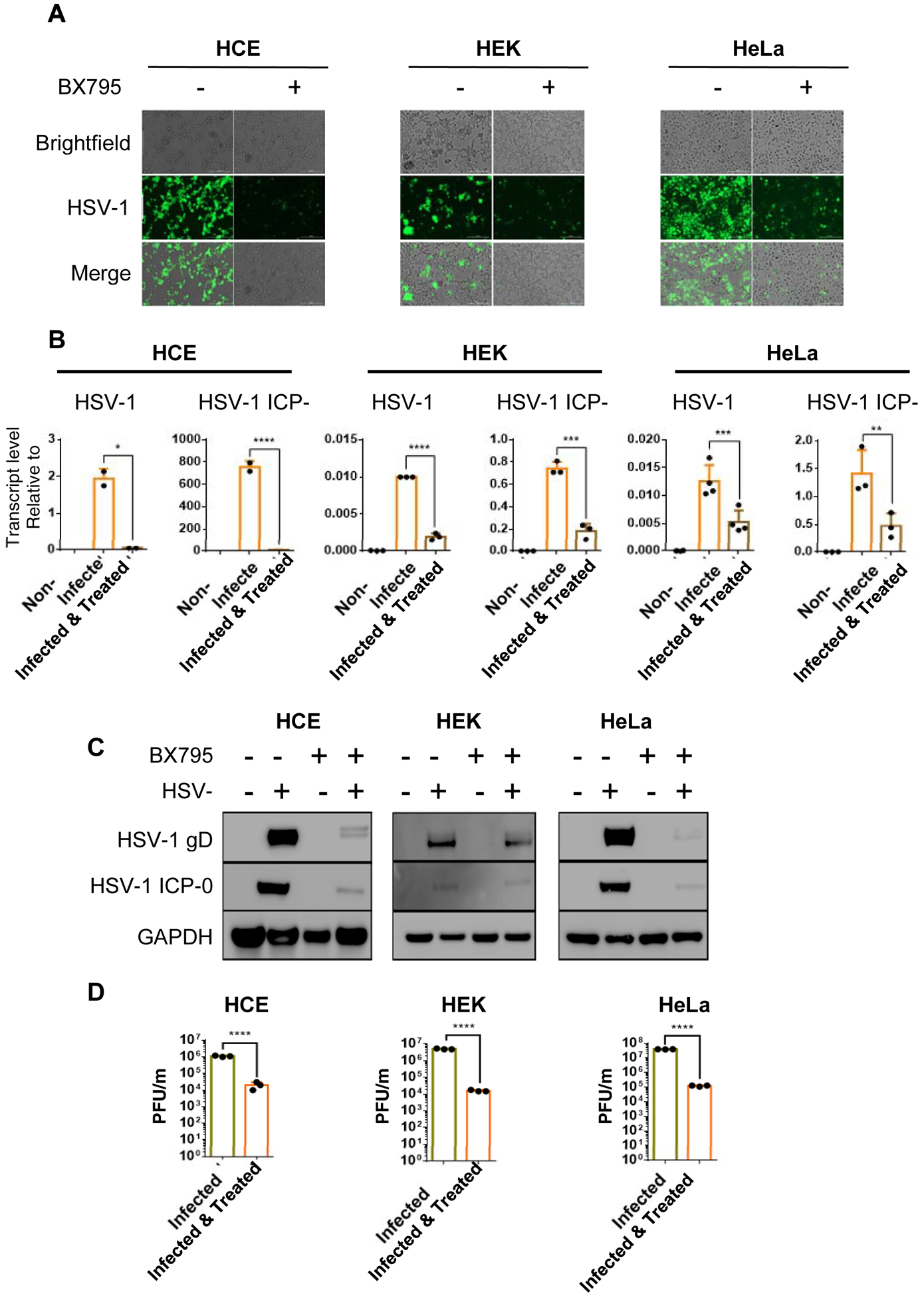

We next investigated antiviral efficacy of BX795 in HCE, HEK, and HeLa cell lines. All cell lines were seeded in 6 well plates at the density of 0.5×106/well and allowed to grow. Upon confluence, HSV-1 GFP reporter virus 17 GFP (0.1 MOI) was used to infect cells and subsequently cells were treated with BX795 (10μM) at 2hpi. Similar to HCEs and HeLa, first HEK cells were imaged using a fluorescence microscope at 24hpi and were collected using Hank’s buffer for qRT-PCR, immunoblots, and plaque assay. Significant decrease in GFP reporter expression of HSV-1 was seen on imaging. qRT-PCR and immunoblots showed reduction of ICP-0 and gD transcripts levels, as well as downregulation of ICP-0 and gD protein expression in BX795 treated samples respectively (Figure. 2A, B, & C). The expression of gD in HEK is not as downregulated as in HCE and HeLa. However, as compared to non-treated HEK cells, the gD expression in BX795 treated HEK cells is approximately 50% lower. In addition, a smaller number of infectious virus particles were also observed in HEK cells as a result of the BX795 administration (Figure. 2D).

Figure 2: BX795 is effective against HSV-1 infection of HCE, HEK and HeLa cell line.

HCE, HEK and HeLa cells were infected with 17GFP strain of HSV-1 upon confluency. 10μM concentration of BX795 was added to infected cell lines 2hpi and images were taken at 24hpi after which cells were collected using Hank’s buffer. A) Fluorescence microscope images of infected and treated HCE, HEK, and HeLa cell lines. B) Viral transcripts levels of immediate early gene ICP-0 and late gene gD mRNA of infected and treated HCE, HEK, and HeLa cell lines were estimated by qRT-PCR C) Total protein levels were quantified via western blotting method where the samples were immunoblotted for ICP-0 and gD protein in non infected, infected and infected as well as treated and treated only HCE, HEK, and HeLa cell lines. GAPDH was used as the loading control. D) Infectious virion particles in infected and treated HCE, HEK, and HeLa cell lines were quantified via plaque assay. Student’s T-test was used to compare transcripts levels of viral proteins as well as plaque assay in non-treated and treated cells. **<0.005 ***<0.0005 ****<0.00005.

3.3. BX795 treatment directly suppresses HSV infection while reducing cytokine induction.

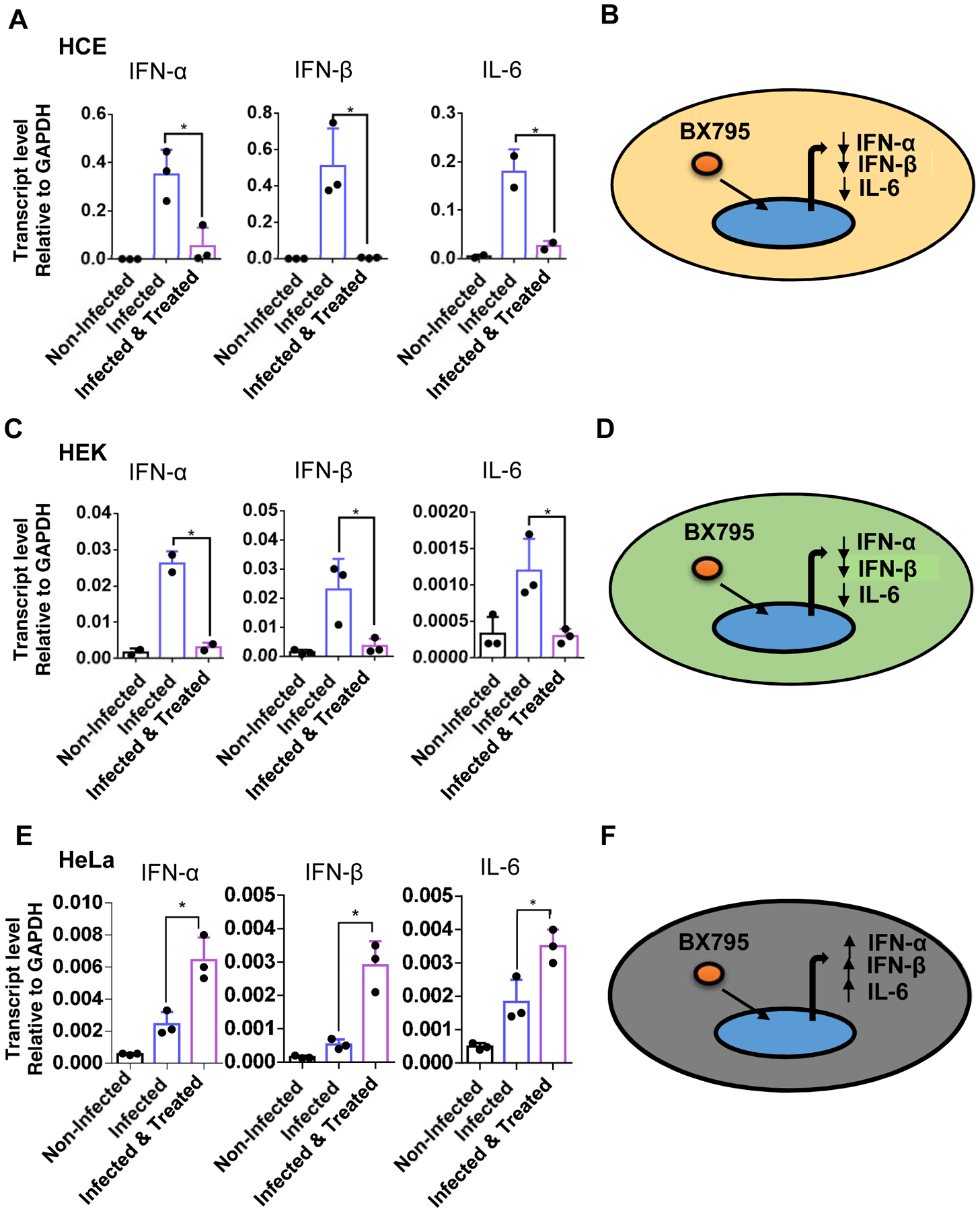

Upon HSV infection certain cytokines such as interferons −α, −β and IL-6 are induced as part of the essential antiviral defense mechanisms. Cytokine induction can generate unduly stress conditions, which may not be healthy for cells. A non-toxic and effective antiviral drug should not only block infection but also, as a direct measure of efficacy, reduce cytokine induction. Thus, to ensure that BX795 treatment inhibits infection and reduces cytokine production; we decided to quantify the cytokine response in our cell lines. A qRT-PCR analysis was performed to assess IFN- α, IFN- β, and IL-6 transcript levels in three different cell lines (Figure 3). Our results showed that BX795 treated cells demonstrated differential expression of the transcripts levels of IFN- α, IFN- β, and IL-6. Interestingly transcript levels of the cytokines found to be increased in HeLa as compared to HEK and HCE as a result of BX795 treatment (Figure 3). While this anomaly was not expected it does show interesting differences in the way individual cell lines respond to infection and treatment.

Figure 3: BX795 administration directly suppresses infection while reducing cytokine induction in HCE and HEK cell lines.

HeLa, HEK, and HCE were infected with HSV-1 GFP reporter virus 17 strain (0.1MOI). At 2hpi, cells were mock-treated or treated with the BX795 at the concentration of 10μM in the fresh culture medium. At 24hpi cells were collected, and Interferon-α, Interferon-β, and interleukin-6 expression levels was measured in HeLa, HEK, and HCE using qRT-PCR. Transcript levels of Interferon-α, Interferon-β, and interleukin-6 in response to BX795 administration as well as schematic of cytokine response of A) HeLa B) HEK. C) HCEs. Student’s T-test was used to compare transcripts levels of cytokines in non-treated and treated cells *<0.05 **<0.005 ***<0.0005 ****<0.00005.

3.4. Two separate cell line-specific mechanisms cause antiviral effects.

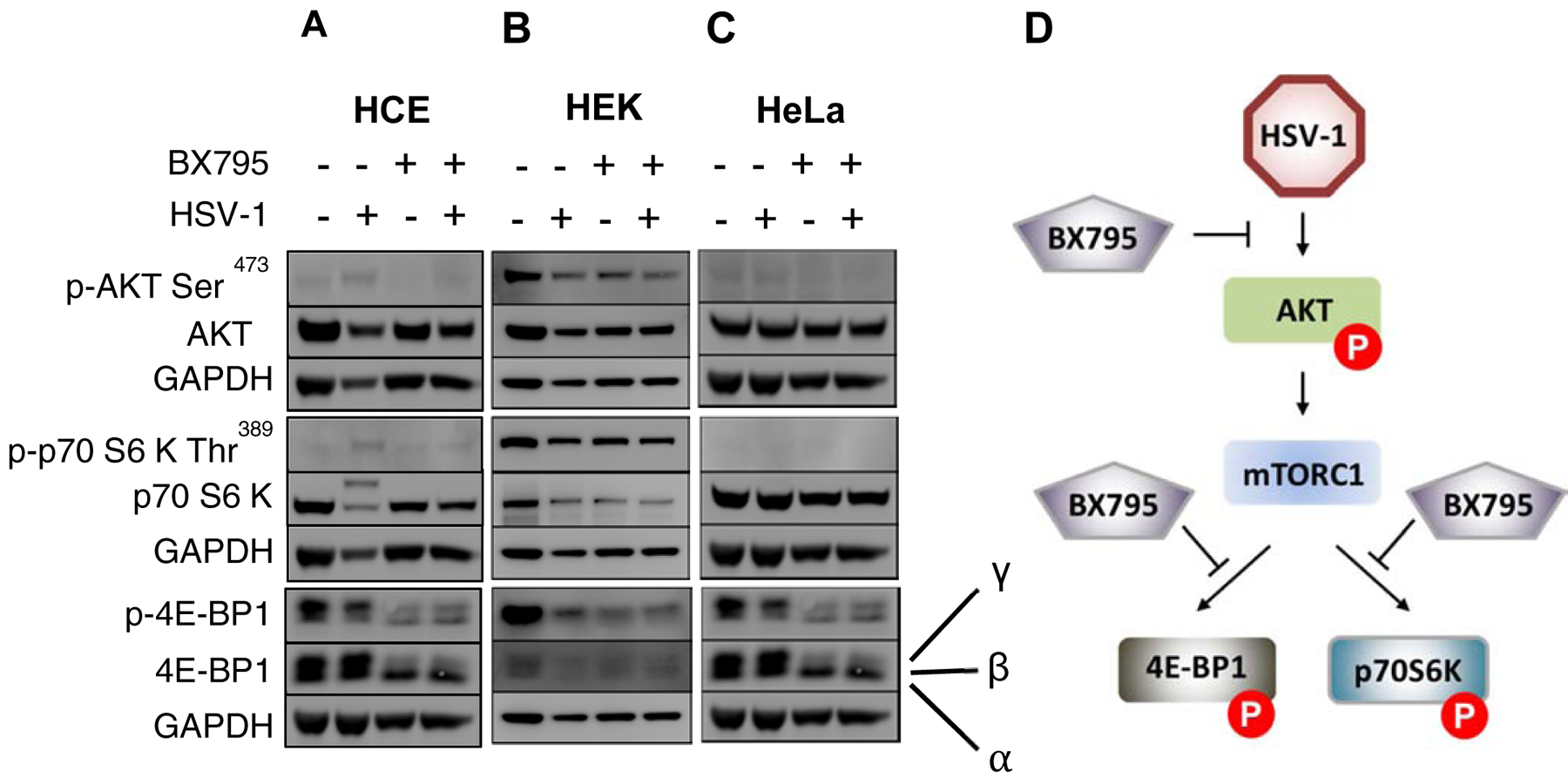

Since inhibition of AKT phosphorylation and its downstream effectors was suggested as a possible mechanism behind the antiviral action of BX795 (Yadavalli et al., 2019;Jaishankar et al., 2018), we, decided to examine these proteins to investigate any cell-type differences in the mechanism of action of BX795. We performed immunoblots analysis to assess the total and phosphorylated levels of AKT, 4E-BP1 and p70 S6 kinase in HCEs, HeLa and HEK cell lines. The immunoblots showed decreased phosphorylation of AKT, 4E-BP1, and p70 S6 kinase with BX795 treatment at therapeutic concentration (10μM) in HeLa and HCE. Additionally, BX795 not only decreased the phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase but also reduced the expression of total p70 S6 kinase in HCE cells. In contrast, we observed constitutive phosphorylation of AKT, p70 S6 kinase, and hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in infected as well as non-infected HEK cells and BX795 did not affect the total and phosphorylation levels of AKT, 4E-BP1, and p70 S6 kinase in HEK cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4: BX795 inhibits virion synthesis of HSV-1 by hindering the phosphorylation of AKT, p70 S6 Kinase, and hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in HeLa and HCEs but not in HEK cells.

HeLa, HEK, and HCE cells lines were infected with 0.1MOI HSV-1 GFP reporter virus 17 GFP and mock-treated or treated with BX795 at the concentration of 10μM at 2hpi in the fresh culture medium. Total protein levels of AKT, 4E-BP1, and p70 S6 Kinase and their phosphorylation status were analyzed by immunoblotting at 24hpi. Immunoblots of the phosphorylated and total protein levels of AKT, 4E-BP1, and p70 S6 kinase in A)HeLa. B) HEK. C) HCE. D) Schematic of the BX795 target in HeLa and HCE.

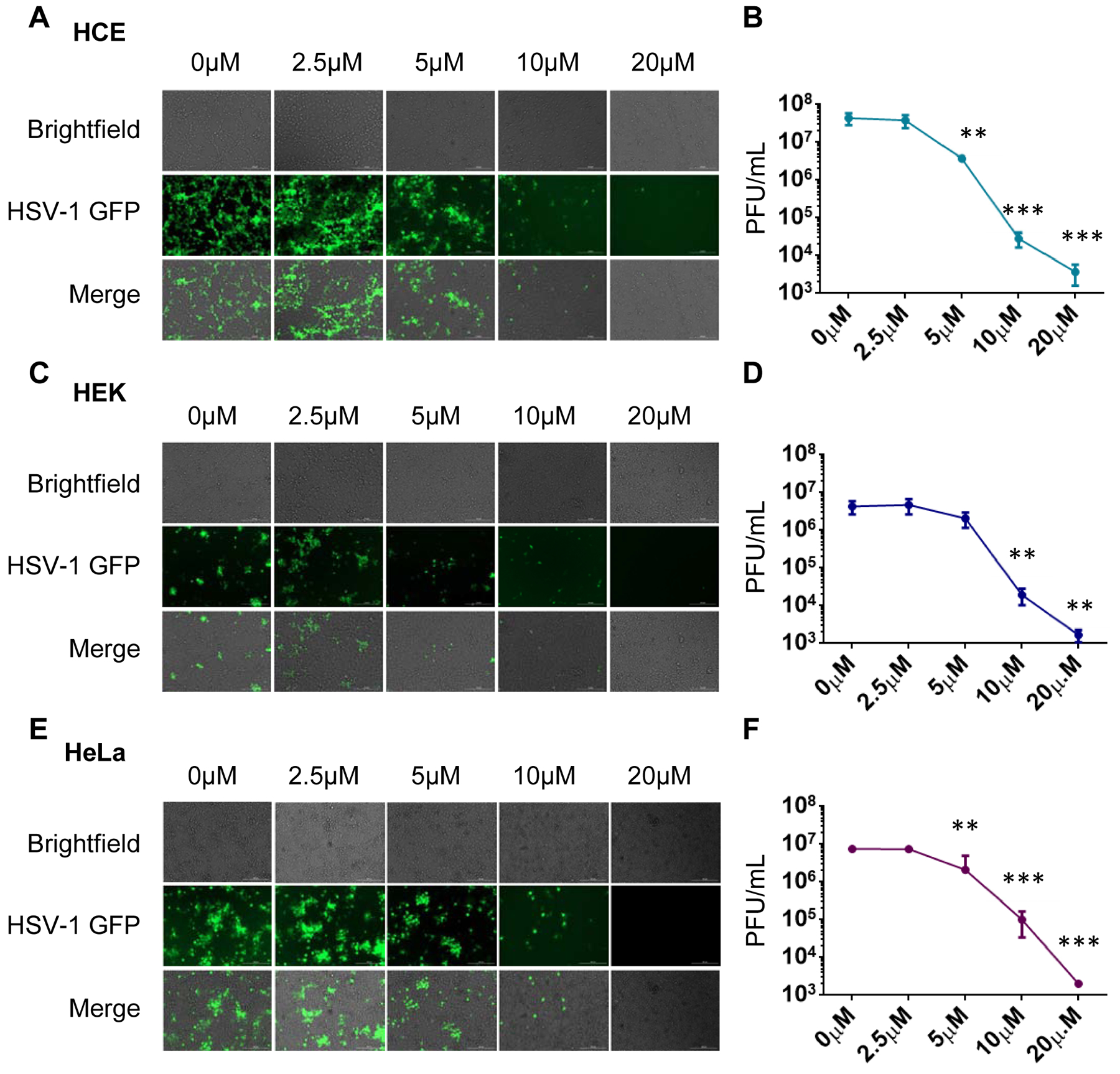

3.5. Antiviral efficacy of BX795 increases with increasing concentration

Next, in order to characterize BX795 as a dose-dependent antiviral compound, the dose-effect relationship of BX795 and HSV-1 infection was studied in HCE, HEK, and HeLa cell lines. All cell lines were seeded at the density of 0.35×106/well in 12 well plates and allowed to grow. Upon confluence, cells were infected with HSV-1 GFP reporter virus 17 GFP (0.1 MOI), and subsequently, at 2hpi cells were treated with different concentrations of BX795 ranged from 2.5μM to 20μM. Similar to HCEs and HeLa, first HEK cells were imaged using a fluorescence microscope at 24hpi and were collected using Hank’s buffer for plaque assay. The decrease in GFP reporter expression of HSV-1 was seen with an increasing concentration of BX795 with the highest GFP reporter expression at 2.5μM and lowest at 20μM on imaging in all cell lines. Plaque assay further supported our findings on images with a linear decrease in viral plaques with an increasing concentration of BX795 in ocular and non ocular cell lines (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Comparison of the dose-effect relationship of BX795 in HeLa, HEK, and HCE cells.

HeLa, HEK, and HCE cell lines were infected with 0.1MOI HSV-1 GFP reporter virus 17 GFP and mock-treated or treated with BX795 at the concentration range from 2.5μM to 10μM at 2hpi in the fresh culture medium. Images were taken with a fluorescence microscope, and cells were collected using Hank’s buffer. A) Images of HCE cell line infected and treated with BX795 concentration ranged from 2.5μM to 20μM. B) Dose effect relationship of BX795 in HCE at the concentration range from 2.5μM to 20uM using plaque assay. C) Images of HEK cell line infected and treated with BX795 concentration ranged from 2.5μM to 20μM. D) Dose effect relationship of BX795 in HEK at the concentration range from 2.5uM to 20μM using plaque assay. E) Images of HeLa cell line infected and treated with BX795 concentration ranged from 2.5μM to 20μM. F) Dose effect relationship of BX795 in HeLa at the concentration range from 2.5μM to 20μM using plaque assay. The data is presented as means ± SD. One-way ANOVA was used to compare plaques in HCE, HEK and HeLa at different concentration of BX795 with nontreated cells. **<0.005 ***<0.0005.

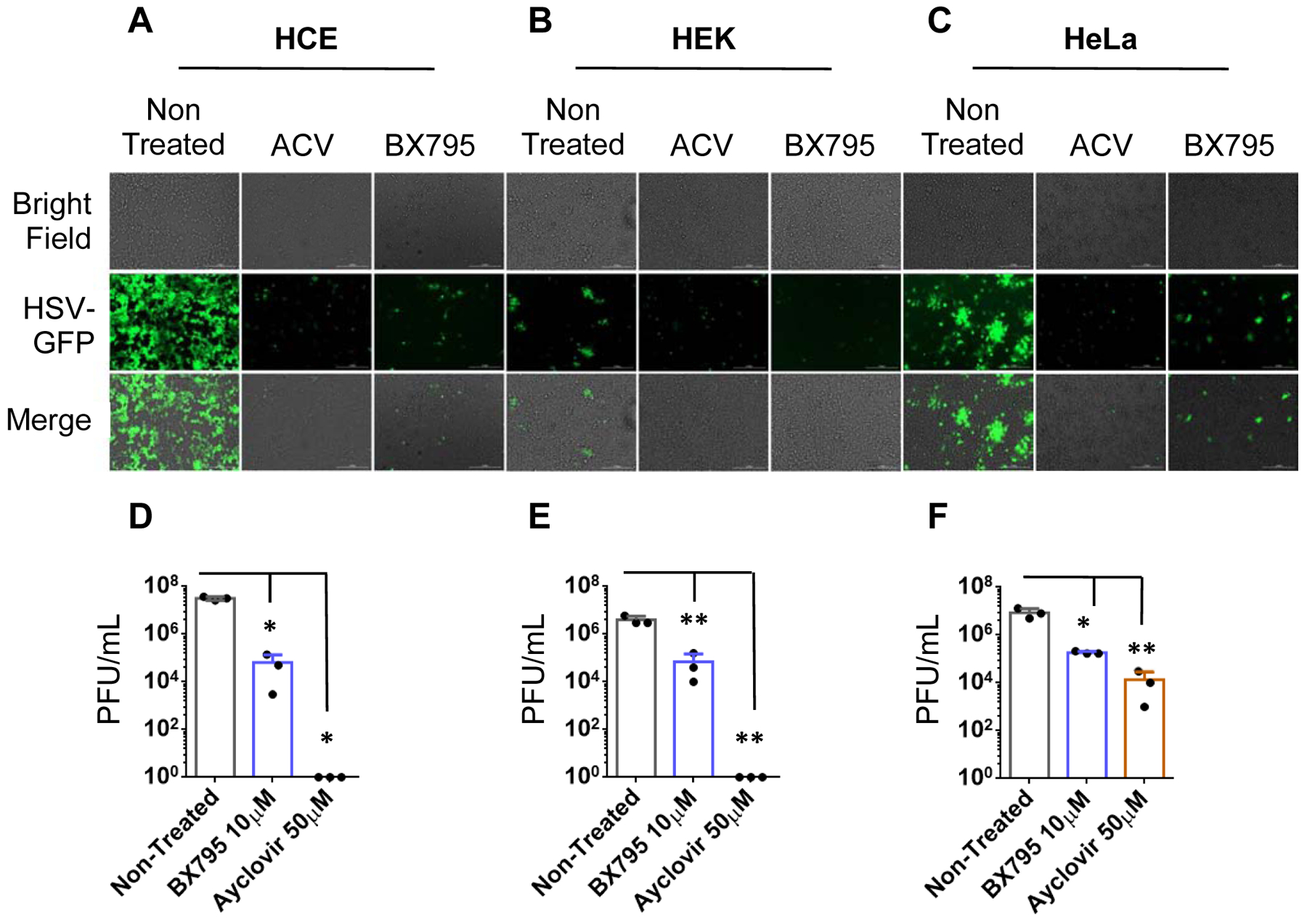

3.6. Antiviral efficacy of BX795 is comparable to Acyclovir in HCE, HEK, and HeLa cells

Since Acyclovir is the current standard of care for HSV infections, we decided to examine its relative antiviral efficacy against BX795. HCE, HEK, and HeLa at the density of 0.35×106/well in 12 well plates were seeded and allowed to grow until they turned confluent. All cell lines were infected with HSV-1 GFP reporter virus 17 GFP (0.1 MOI) and treated with acyclovir (50μM) and BX795 (10μM). Cells were imaged at 24hpi and collected using Hank’s buffer for plaque assay (Figure 6). It was evident that antiviral efficacy of BX795 was comparable to acyclovir which signify the validity and reliability of our experiments with BX795.

Figure 6: BX795 demonstrates similar antiviral efficacy as Acyclovir.

HCE, HEK, and HeLa cell lines were seeded in 12 well plates and allowed to grow overnight. Upon confluence, cells were infected and treated with either Acyclovir (50μM) or BX795 (10μM) at 2hpi. Cells were imaged at 24hpi and collected using Hank’s buffer for plaque assay. A) Images of infected and Acyclovir or BX795 treated HCE cells. B) Images of infected and Acyclovir or BX795 treated HEK cells. C) Images of infected and Acyclovir or BX795 treated HeLa cells. D) Viral titers of infected and Acyclovir or BX795 treated HCE cells. E) Viral titers of infected and Acyclovir or BX795 treated HEK cells. F) Viral titers of infected and Acyclovir or BX795 treated HeLa cells. One-way ANOVA was used to determine the significance to mock-treated cells. *<0.05 **<0.005 ***<0.0005.

4. Discussion

BX795 is an emerging antiviral agent that has demonstrated excellent antiviral activity against HSV-1 infection of murine corneas, both in vitro and in vivo. It exerts antiviral activity by inhibiting the synthesis of viral proteins (Yadavalli, Suryawanshi et al., 2019;Jaishankar et al., 2018), whereas other available treatment options for HSV-1 inhibit viral DNA synthesis (Chatis and Crumpacker, 1992;Poole and James, 2018). In this study, we extended our work on BX795 to determine its antiviral efficacy, cytotoxicity, cytokine response, and mechanism of action on various human cell lines. This line of investigation is important to understand the broader antiviral efficacy of BX795 and its mode(s) of antiviral action. We found that the previously identified therapeutic concentration of BX795 (10μM) exerts similar antiviral efficacy in all cell lines tested. These results depicted that the antiviral efficacy of BX795 was not limited to any specific cell types. Our choice of HCE cell line in this study was meant to compare and contrast an ocular cell line using identical HSV-1 strains and assay conditions as the other two cell lines. As HSV-1 causes oral, neurologic, respiratory, vaginal, and skin infections in addition to ocular infection, our studies shed more light on the activity of BX795 in the aforementioned cell types (Hopkins et al., 2018;Koujah et al., 2019;Lobo et al., 2019). Our results demonstrate that antiviral efficacies are very similar in ocular vs. non ocular cell types.

BX795 has already been used as an anti-cancer drug and has been studied to decrease the viability of oral cancer cell lines (Bai et al., 2015) Therefore, it was important for us to determine whether HEK, HeLa, and HCE will remain viable at the therapeutic concentration of BX795. Our viability assay results showed that survival of HCEs, HeLa, and HEK was not affected at the therapeutic concentration of BX795, which is also supported by some previous findings (Jaishankar et al., 2018;Su et al., 2017). The CC50 for HeLa, HEK, and HCE (46.35μM, 76.5μM, and 51μM) were far above the antiviral concentration of BX795 (10μM), suggesting that the therapeutic window for this drug is safe. The nontoxicity and antiviral efficacy of the therapeutic concentration of BX795 on different human cell lines show the use of therapeutic concentration of BX795 can be extended beyond ocular infection.

HSV-1 infection activates the immune system and cytokines play an important role in this process to protect the cells from viral infection. As cytokines have both pre-inflammatory and post-inflammatory role, we decided to determine the cytokine response to HSV-1 infection in HeLa, HEK, and HCEs upon BX795 treatment. The cytokine response of HeLa contradicted the results of HCE and HEK. Transcripts levels of IFN-α, IFN-β, and IL- 6 elevated in infected HeLa cells with BX795 administration and lowered in HEK and HCE. The different cytokine response, along with viral suppression of infected HeLa cells with BX795 treatment depicts BX795 antiviral mechanism is independent of cytokine response.

We next investigated the difference in the mechanism of antiviral activity of BX795 in different human cell lines. HSV-1 has been previously implicated in hijacking the host protein synthesis machinery for its own benefit. HSV-1 activates AKT via phosphorylation at the serine-473 site in addition to producing its own AKT mimetic Us3 protein kinase, which in turn activates p70 S6 Kinase and also causes hyperphosphorylation 4E-BP1. (Zhou and Huang, 2010;Narayanan et al., 2009;Diehl and Schaal, 2013). Us3 protein kinase has also been studied to cause hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1(Walsh and Mohr, 2011;Norman and Sarnow, 2010). Previous work on BX795 reported it could prevent the phosphorylation of AKT and hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and in this way, hinders viral protein synthesis. In this study, proteins isolated from all HSV-1 infected and BX795 treated cell lines were immunoblotted for AKT, 4E-BP1, and p70 S6 Kinase and their phosphorylated forms, respectively. We found that BX795 decreased the phosphorylation of AKT, 4E-BP1, and p70 S6 Kinase in HeLa and HCEs, whereas no change in the phosphorylation status of any of these proteins was observed in HEK cells. These results showed that HSV-1 is benefited by phosphorylating AKT and its downstream proteins 4E-BP1 and p70 S6 kinase in HeLa and HCEs and BX795 counteract these viral targets. They also direct our attention towards a possible different mechanism through which BX795 exerts its anti-HSV-1 efficacy in HEK cell type. Further studies are needed to determine the mode of anti-HSV-1 action of BX795 in HEK cells. Regardless of no change in phosphorylation levels of AKT, 4E-BP1, and p70 S6 Kinase in HEK cells, BX795 antiviral efficacy remained the same in all cell lines, including HEK cells.

Interestingly, BX795 not only decreased the phosphorylation of p70 S6 Kinase but also reduced the expression of this protein in HCEs. p70 S6 Kinase is a downstream target of mTORC1 and plays an important role in protein synthesis by phosphorylating S6 which regulates mRNA translation. To increase its own protein synthesis, HSV-1 augments phosphorylation of p70 S6 kinase, which in turn phosphorylates S6 protein (Tovilovic et al., 2013). S6 protein is the component of ribosomal subunit 40S and phosphorylation of S6 protein activates protein synthesis (Sweet et al., 1990;Sturgill and Wu, 1991;Erikson, 1991). The decreased expression of p70 S6 Kinase upon BX795 treatment of HCE might be due to decreased transcription of this protein which shows BX795 may suppresses transcription and translation in the host cell. More studies need to be conducted to shed light on how BX795 decreases the expression of p70 S6 kinase.

We also compared the antiviral efficacy of BX795 in all cell lines at different concentration. The BX795 concentration ranged from 2.5μM to 20μM. The drug remained ineffective at 2.5μM in all cell lines however, the magnitude of antiviral efficacy of BX795 increased with increasing concentration of BX795 in ocular as well as non ocular cell lines. Our dose-effect relationship depicted 10μM as the best therapeutic dose of BX795 as BX795 showed optimum antiviral efficacy at this dose in all cell lines. The anti-viral efficacy of BX795 was also compared to acyclovir which was used as positive control. The therapeutic concentration of BX795 (10μM) was found to be comparable to the therapeutic concentration of acyclovir (50μM). The almost similar efficacy of BX795 with current standard of care for herpes simplex virus proves that BX795 is the potent anti-HSV drug.

5. Conclusion

Our results conclude that BX795 exerts potent anti-HSV-1 effects in different human cell lines. Difference in cytokine response of HeLa cells and difference in phosphorylation levels of virally hijacked host proteins in HEK cells infer that BX795 is a versatile drug which exerts its anti-HSV-1 effects through several mechanisms in a cell-type specific manner.

Table: 2.

List of Primers used to amplify cDNA transcripts levels from HSV-1 infected and BX795 treated HEK, HeLa, and HCEs.

| Targets | Directions | Sequences (5′−3′) |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | forward | CAC CAC CAA CTG CTT AGC AC |

| reverse | CCC TGT TGC TGT AGC CAA AT | |

| IFN-α | forward | GAT GGC AAC CAG TTC CAG AAG |

| reverse | AAA GAG GTT GAA GAT CTG CTG GAT | |

| IFN-ß | forward | CTC CAC TAC AGC TCT TTC CAT |

| reverse | GTC AAA GTT CAT CCT GTC CTT | |

| IL-6 | forward | AAC TCC TTC TCC AGA AGC GCC |

| reverse | GTG GGG CGG CTA CAT CTT T | |

| HSV-1 | forward | GTG CTG CGC CAA GAA AAT |

| ICP-0 | reverse | TCA ACT CGC AGA CAC GAC TC |

| HSV-1 gD | forward | TAC AAC CTG ACC ATC GCT TC |

| reverse | GCC CCC AGA GAC TTG TTG TA |

Highlights.

BX795 demonstrates attributes of a potent small molecule inhibitor of herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) infection.

At therapeutic concentration BX795 is well tolerated by human cell lines.

It demonstrates strong antiviral efficacy while inducing differential cytokine responses in human cell lines.

The mechanism of antiviral activity of BX795 in HEK cells is different from HCE and HeLa cell lines.

6. Funding Source

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 EY024710) to DS

Abbreviations

- HSV-1

Herpes Simplex Virus

- HeLa

Henrietta Lacks

- HCE

Human corneal epithelial

- HEK

Human embryonic kidney

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- IFN-α

Interferon alpha

- IFN-β

Interferon beta

- IL-6

Interleukin 6.

- ICP-0

Infected cell polypeptide

- gD

Glycoprotein D

- gB

Glycoprotein B

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- P/S

Penicillin and streptomycin

- PFU

plaque forming units

- CC50

Cytotoxic concentration

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1).Agelidis A, Koujah L, Suryawanshi R, Yadavalli T, Mishra YK, Adelung R, Shukla D, 2019. An Intra-Vaginal Zinc Oxide Tetrapod Nanoparticles (ZOTEN) and Genital Herpesvirus Cocktail Can Provide a Novel Platform for Live Virus Vaccine. Front. Immunol 10, 500. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00500 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Azher TN, Yin XT, Stuart PM, 2017. Understanding the Role of Chemokines and Cytokines in Experimental Models of Herpes Simplex Keratitis. J. Immunol. Res 2017, 7261980. doi: 10.1155/2017/7261980 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Bai LY, Chiu CF, Kapuriya NP, Shieh TM, Tsai YC, Wu CY, Sargeant AM, Weng JR, 2015. BX795, a TBK1 inhibitor, exhibits antitumor activity in human oral squamous cell carcinoma through apoptosis induction and mitotic phase arrest. Eur. J. Pharmacol 769, 287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.11.032 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Chatis PA, Crumpacker CS, 1992. Resistance of herpesviruses to antiviral drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 36, 1589–1595. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.8.1589 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Clive D, Turner NT, Hozier J, Batson AG, Tucker WE, 1983. Preclinical toxicology studies with acyclovir: genetic toxicity tests. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol 3, 587–602. doi: 10.1016/s0272-0590(83)80109-2 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Costa BKD, Sato DK, 2019. Viral encephalitis: a practical review on diagnostic approach and treatment. J. Pediatr. (Rio J) doi: S0021–7557(19)30429–2 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Cunningham AL, Taylor R, Taylor J, Marks C, Shaw J, Mindel A, 2006. Prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in Australia: a nationwide population based survey. Sex. Transm. Infect 82, 164–168. doi: 82/2/164 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Diehl N, Schaal H, 2013. Make yourself at home: viral hijacking of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Viruses 5, 3192–3212. doi: 10.3390/v5123192 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Erikson RL, 1991. Structure, expression, and regulation of protein kinases involved in the phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6. J. Biol. Chem 266, 6007–6010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Fleischer R, Johnson M, 2010. Acyclovir nephrotoxicity: a case report highlighting the importance of prevention, detection, and treatment of acyclovir-induced nephropathy. Case Rep. Med 2010, 10.1155/2010/602783. Epub 2010 Aug 31. doi: 10.1155/2010/602783 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Hopkins J, Yadavalli T, Agelidis AM, Shukla D, 2018. Host Enzymes Heparanase and Cathepsin L Promote Herpes Simplex Virus 2 Release from Cells. J. Virol 92, 10.1128/JVI.01179-18. Print 2018 Dec 1. doi: e01179–18 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Jaishankar D, Yakoub AM, Yadavalli T, Agelidis A, Thakkar N, Hadigal S, Ames J, Shukla D, 2018. An off-target effect of BX795 blocks herpes simplex virus type 1 infection of the eye. Sci. Transl. Med 10, 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan5861. doi: eaan5861 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Jaishankar D, Shukla D, 2016. Genital Herpes: Insights into Sexually Transmitted Infectious Disease. Microb. Cell 3, 438–450. doi: 10.15698/mic2016.09.528 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Jayamanne DG, Vize C, Ellerton CR, Morgan SJ, Gillie RF, 1997. Severe reversible ocular anterior segment ischaemia following topical trifluorothymidine (F3T) treatment for herpes simplex keratouveitis. Eye (Lond) 11 (Pt 5), 757–759. doi: 10.1038/eye.1997.193 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Jiang YC, Feng H, Lin YC, Guo XR, 2016. New strategies against drug resistance to herpes simplex virus. Int. J. Oral Sci 8, 1–6. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2016.3 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Jordheim LP, Durantel D, Zoulim F, Dumontet C, 2013. Advances in the development of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues for cancer and viral diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 12, 447–464. doi: 10.1038/nrd4010 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Koganti R, Yadavalli T, Shukla D, 2019. Current and Emerging Therapies for Ocular Herpes Simplex Virus Type-1 Infections. Microorganisms 7, 10.3390/microorganisms7100429. doi: E429 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Koujah L, Suryawanshi RK, Shukla D, 2019. Pathological processes activated by herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) infection in the cornea. Cell Mol. Life Sci 76, 405–419. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2938-1 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Lobo AM, Agelidis AM, Shukla D, 2019. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex keratitis: The host cell response and ocular surface sequelae to infection and inflammation. Ocul. Surf 17, 40–49. doi: S1542–0124(18)30280–5 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Maudgal PC, Van Damme B, Missotten L, 1983. Corneal epithelial dysplasia after trifluridine use. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol 220, 6–12. doi: 10.1007/bf02307009 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Narayanan SP, Flores AI, Wang F, Macklin WB, 2009. Akt signals through the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway to regulate CNS myelination. J. Neurosci 29, 6860–6870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0232-09.2009 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Norman KL, Sarnow P, 2010. Herpes Simplex Virus is Akt-ing in translational control. Genes Dev 24, 2583–2586. doi: 10.1101/gad.2004510 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Poole CL, James SH, 2018. Antiviral Therapies for Herpesviruses: Current Agents and New Directions. Clin. Ther 40, 1282–1298. doi: S0149–2918(18)30311–4 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Sharma P, Chawla A, Arora S, Pawar P, 2012. Novel drug delivery approaches on antiviral and antiretroviral agents. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res 3, 147–159. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.101007 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Spiegal DM, Lau K, 1986. Acute renal failure and coma secondary to acyclovir therapy. JAMA 255, 1882–1883. doi: 10.1001/jama.1986.03370140080027 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Straface G, Selmin A, Zanardo V, De Santis M, Ercoli A, Scambia G, 2012. Herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol 2012, 385697. doi: 10.1155/2012/385697 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Sturgill TW, Wu J, 1991. Recent progress in characterization of protein kinase cascades for phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1092, 350–357. doi: S0167–4889(97)90012–4 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Su AR, Qiu M, Li YL, Xu WT, Song SW, Wang XH, Song HY, Zheng N, Wu ZW, 2017. BX-795 inhibits HSV-1 and HSV-2 replication by blocking the JNK/p38 pathways without interfering with PDK1 activity in host cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 38, 402–414. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.160 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Sun B, Wang Q, Pan D, 2019. Mechanisms of herpes simplex virus latency and reactivation. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 48, 89–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Sweet LJ, Alcorta DA, Erikson RL, 1990. Two distinct enzymes contribute to biphasic S6 phosphorylation in serum-stimulated chicken embryo fibroblasts. Mol. Cell. Biol 10, 2787–2792. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.6.2787 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Tovilovic G, Ristic B, Siljic M, Nikolic V, Kravic-Stevovic T, Dulovic M, Milenkovic M, Knezevic A, Bosnjak M, Bumbasirevic V, Stanojevic M, Trajkovic V, 2013. mTOR-independent autophagy counteracts apoptosis in herpes simplex virus type 1-infected U251 glioma cells. Microbes Infect 15, 615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.04.012 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Udell IJ, 1985. Trifluridine-associated conjunctival cicatrization. Am. J. Ophthalmol 99, 363–364. doi: 0002-9394(85)90372-1 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Wald A, Corey L, 2007. Persistence in the population: epidemiology, transmission, in: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, Moore PS, Roizman B, Whitley R, Yamanishi K (Eds.), Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis, Cambridge. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Walsh D, Mohr I, 2011. Viral subversion of the host protein synthesis machinery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 9, 860–875. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2655 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Whitley R, Bernard R, 2001. Herpes Simplex Virus Infections 357, 1513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Yadavalli T, Ames J, Agelidis A, Suryawanshi R, Jaishankar D, Hopkins J, Thakkar N, Koujah L, Shukla D, 2019. Drug-encapsulated carbon (DECON): A novel platform for enhanced drug delivery. Sci. Adv 5, eaax0780. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax0780 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Yadavalli T, Suryawanshi R, Ali M, Iqbal A, Koganti R, Ames J, Aakalu VK, Shukla D, 2019. Prior inhibition of AKT phosphorylation by BX795 can define a safer strategy to prevent herpes simplex virus-1 infection of the eye. Ocul. Surf . doi: S1542–0124(19)30421–5 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Yadavalli T, Suryawanshi R, Ali M, Iqbal A, Koganti R, Ames J, Aakalu VK, Shukla D, 2019. Prior inhibition of AKT phosphorylation by BX795 can define a safer strategy to prevent herpes simplex virus-1 infection of the eye. Ocul. Surf . doi: S1542–0124(19)30421–5 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Yildiz C, Yasemin O, Safak G, Ali Bulent C, Rezan T, 2013. Acute kidney injury due to acyclovir 2, 38. doi: 10.1007/s13730-012-0035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Zhou H, Huang S, 2010. The complexes of mammalian target of rapamycin. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci 11, 409–424. doi: CPPS-56 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]