Abstract

Background

The ideal quantity of dietary protein for formula‐fed low birth weight infants is still a matter of debate. Protein intake must be sufficient to achieve normal growth without leading to negative effects such as acidosis, uremia, and elevated levels of circulating amino acids.

Objectives

To determine whether higher (≥ 3.0 g/kg/d) versus lower (< 3.0 g/kg/d) protein intake during the initial hospital stay of formula‐fed preterm infants or low birth weight infants (< 2.5 kilograms) results in improved growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes without evidence of short‐ or long‐term morbidity.

Specific objectives were to examine the following comparisons of interventions and to conduct subgroup analyses if possible.

1. Low protein intake if the amount was less than 3.0 g/kg/d.

2. High protein intake if the amount was equal to or greater than 3.0 g/kg/d but less than 4.0 g/kg/d.

3. Very high protein intake if the amount was equal to or greater than 4.0 g/kg/d.

Search methods

We used the standard search strategy of Cochrane Neonatal to search the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 8), in the Cochrane Library (August 2, 2019); OVID MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily, and Ovid MEDLINE(R) (to August 2, 2019); MEDLINE via PubMed (to August 2, 2019) for the previous year; and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (to August 2, 2019). We also searched clinical trials databases and the reference lists of retrieved articles for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomized trials.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs contrasting levels of formula protein intake as low (< 3.0 g/kg/d), high (≥ 3.0 g/kg/d but < 4.0 g/kg/d), or very high (≥ 4.0 g/kg/d) in formula‐fed hospitalized neonates weighing less than 2.5 kilograms. We excluded studies if infants received partial parenteral nutrition during the study period, or if infants were fed formula as a supplement to human milk.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane and the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence.

Main results

We identified six eligible trials that enrolled 218 infants through searches updated to August 2, 2019. Five studies compared low (< 3 g/kg/d) versus high (3.0 to 4.0 g/kg/d) protein intake using formulas that kept other nutrients constant. The trials were small (n = 139), and almost all had methodological limitations; the most frequent uncertainty was about attrition. Low‐certainty evidence suggests improved weight gain (mean difference [MD] 2.36 g/kg/d, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.31 to 3.40) and higher nitrogen accretion in infants receiving formula with higher protein content (3.0 to 4.0 g/kg/d) versus lower protein content (< 3 g/kg/d), while other nutrients were kept constant. No significant differences were seen in rates of necrotizing enterocolitis, sepsis, or diarrhea. We are uncertain whether high versus low protein intake affects head growth (MD 0.37 cm/week, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.58; n = 18) and length gain (MD 0.16 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.34; n = 48), but sample sizes were small for these comparisons.

One study compared high (3.0 to 4.0 g/kg/d) versus very high (≥ 4 g/kg/d) protein intake (average intakes were 3.6 and 4.1 g/kg/d) during and after an initial hospital stay (n = 77). Moderate‐certainty evidence shows no significant differences in weight gain or length gain to discharge, term, and 12 weeks corrected age from very high protein intake (4.1 versus 3.6 g/kg/d). Three of the 24 infants receiving very high protein intake developed uremia.

Authors' conclusions

Higher protein intake (≥ 3.0 g/kg/d but < 4.0 g/kg/d) from formula accelerates weight gain. However, limited information is available regarding the impact of higher formula protein intake on long‐term outcomes such as neurodevelopment. Research is needed to investigate the safety and effectiveness of protein intake ≥ 4.0 g/kg/d.

Plain language summary

Higher versus lower protein intake in formula‐fed low birth weight infants

Review question

Does feeding preterm or low birth weight infants (< 2.5 kilograms) higher protein intake during the initial hospital stay improve growth and developmental outcomes?

Background

Infants grow quickly and need more protein for each kilogram of body weight than older children and adults. Infants born with low birth weight, for example, those who are born prematurely, need more protein because of their fast growth rates.

Study characteristics

We identified six eligible trials that enrolled a total of 218 infants through searches updated to August 2, 2019.

Key results

Higher protein intake (3 to 4 versus less than 3 grams of protein per kilogram) resulted in slightly greater weight gain, of around 2 grams per kilogram per day. We are uncertain whether this difference in protein intake affects head and length growth because not many infants were studied. Existing research does support specific recommendations regarding formula with protein content that provides more than 4 g/kg/d. No harmful effects were observed.

Certainty of evidence

The review was limited in the conclusions made because differences in protein content among comparison groups in some individual trials were small and formulas differed substantially across studies; some studies included healthier and more mature preterm infants. Information on long‐term outcomes is limited.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. High protein compared to low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria) in formula‐fed low birth weight infants.

| Patient or population: formula‐fed low birth weight infants Setting: neonatal care facilities in USA, Canada, and Sweden Intervention: HIGH protein intake Comparison: LOW protein intake | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | №. of participants (studies) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria) | Risk with high protein intake | |||||

| Weight gain (g/kg/d) | Mean growth parameters ‐ weight gain (g/kg/d) was 0 | MD 2.36 higher (1.31 higher to 3.4 higher) | ‐ | 114 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | Evidence suggests that high vs low protein intake increases weight gain, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by risks of bias and heterogeneity |

| Linear growth (cm/week) | Mean growth parameters ‐ linear growth (cm/week) was 0 | MD 0.16 higher (0.02 lower to 0.34 higher) | ‐ | 48 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | Evidence suggests that high vs low protein intake probably leads to little or no difference in the rate of length gain, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by risks of bias and imprecision |

| Head circumference growth (cm/week) | Mean growth parameters ‐ head growth (cm/week) was 0 | MD 0.37 higher (0.16 higher to 0.58 higher) | ‐ | 18 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | Evidence is very uncertain about the effect of protein on head circumference growth, and it may have little to no effect on head circumference growth. but the evidence is very uncertain |

| IQ score and Bayley score at 18 months or later | This outcome was not measured | |||||

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | Study population | Not estimable | 46 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | High vs low protein intake may not increase necrotizing enterocolitis, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by risks of bias and the small sample size | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomized controlled trial. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels for risk of bias (selection, performance, detection, attrition) and moderate heterogeneity.

bDowngraded two levels for risk of bias (selection, performance, detection, attrition) and imprecision. Broad 95% CI; included both higher and lower length gain in estimate.

cDowngraded one level for risk of bias (selection, performance, detection, attrition) and two levels for serious imprecision (one RCT; N = 18).

dDowngraded two levels for risk of bias (selection, performance, detection, attrition) and imprecision.

Summary of findings 2. Very high protein compared to low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria) in formula‐fed low birth weight infants.

| Patient or population: formula‐fed low birth weight infants Setting: neonatal care facilities Intervention: VERY HIGH protein intake Comparison: LOW protein intake | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | №. of participants (studies) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria) | Risk with high protein intake | |||||

| Weight gain | This outcome was not measured | |||||

| Linear growth | This outcome was not measured | |||||

| Head circumference growth | This outcome was not measured | |||||

| IQ score and Bayley score at 18 months or later | This outcome was not measured | |||||

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | This outcome was not measured | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval. | ||||||

Summary of findings 3. Very high protein compared to high protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria) in formula‐fed low birth weight infants.

| Patient or population: formula‐fed low birth weight infants Setting: neonatal care facilities in England Intervention: VERY HIGH protein intake Comparison: HIGH protein intake | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | №. of participants (studies) | Certainty of evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria) | Risk with high protein intake | |||||

| Weight gain (g/d) to discharge | Mean growth parameters ‐ weight gain (g/d) was 0 | MD 3.10 higher (0.04 lower to 6.24 higher) | ‐ | 77 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Moderatea | Evidence suggests that very high protein intake, compared to high protein intake, increases weight gain, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by imprecision |

| Linear growth (cm/week) | Mean growth parameters ‐ linear growth (cm/week) was 0 | MD 0.00 (0.14 lower to 0.14 higher) | ‐ | 77 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Moderatea | Very high protein intake (compared to high protein intake) may have little or no effect on the rate of length gain, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by imprecision |

| Head circumference growth | This outcome was not measured | |||||

| IQ score and Bayley score at 18 months or later | This outcome was not measured | |||||

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | This outcome was not measured | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomized controlled trial. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for imprecision.

Background

Description of the condition

Good nutrition is essential for optimal growth and development of the preterm infant (AAP 2020). Protein is an important component of adequate nutrition, as it provides essential amino acids required for protein synthesis, which is necessary for growth. Hence, the quantity of protein consumed is an important consideration (AAP 2020). The protein requirement for preterm infants can be estimated in one of two ways: estimates based on the protein intake of breast‐fed infants or estimates based on theoretical calculations (the factorial approach). At three to four weeks postnatal age, a preterm infant fed own mother's milk receives approximately 1.4 g/100 mL (Gidrewicz 2014), or about 2.1 to 2.5 g/kg/d of protein. The factorial approach is a theory‐based calculation that sums the requirements for growth and those for replacement of inevitable losses in urine, feces, and skin (Fomon 1991). It is difficult to estimate requirements for protein intake in preterm infants because they may have a high rate of protein turnover and breakdown as a result of immaturity or illness (Hay 1996; Kalhan 2000; Pencharz 1981). Preterm infants have very rapid rates of growth and protein accretion. Based on the factorial approach with the "reference fetus," Ziegler and Fomon estimated the protein intake required for preterm infant growth and nitrogen accretion at 4 g/kg/d of enteral protein for infants with birth weight less than 1200 grams (Ziegler 1976; Ziegler 1981), and at 3.5 g/kg/d for infants with birth weight of 1200 to 1800 grams (AAP 2020). Formulas currently available for preterm infants in North America contain 3 g of protein per 100 kcal. If energy intakes are maintained at the recommended range (Klein 2002), formula‐fed infants would receive about 2.5 to 4 g/kg/d of protein. A disparity is evident between what is provided in own mother's milk versus estimated protein intake based on the factorial approach using the Ziegler‐Fomon reference, and what is contained in preterm formula.

Description of the intervention

Putative risks of higher protein intake include increased concentrations of amino acids, hydrogen ions, and urea as a result of immaturity of amino acid metabolic pathways in preterm infants (Senterre 1983). Preterm infants may not be able to handle higher protein intake efficiently; hence metabolic acidosis and higher plasma levels of amino acids such as tyrosine and phenylalanine concentrations may result (Micheli 1999). Theoretically, these metabolic changes could lead to mental retardation. Additionally, adaptive responses of endocrine and metabolic homeostasis resulting from early nutrition may lead to "metabolic programming," which alters long‐term outcomes of chronic diseases. Renal hypertrophy accompanied by a significant rise in kidney tissue and circulating insulin‐like growth factor‐1 has been reported secondary to high protein intake (Murray 1993). High protein intake in early life may increase risks later in life of obesity (Rolland‐Cachera 1995; Scaglioni 2000), as well as other pathology (Rolland‐Cachera 1995), such as diabetes mellitus (Raiha 2001). Therefore, long‐term consequences of early nutrition need to be considered.

How the intervention might work

Putative benefits of higher protein intake include adequacy of protein for growth of lean tissue, growth of bone and blood constituents, turnover of tissues, synthesis of hormones and enzymes, and maintenance of oncotic pressure (Fomon 1993). In an animal study, higher protein intake was shown to accelerate maturation of the renal tubules (Jakobsson 1990). Deficiency of protein in infants leads to growth failure and, when extreme, can result in edema and lower resistance to infection (Nayak 1989). Some very low birth weight infants have lower lean mass in childhood compared to infants born at term (Gianni 2015), which could be due to suboptimal protein intake in early life.

Why it is important to do this review

Sufficient energy and other nutrients are needed to allow protein to be used for anabolism (Kashyap 1994), rather than as a fuel source. When energy availability is limited, nitrogen balance and protein utilization for tissue synthesis are limited. When protein is used for energy, the amino groups are cleaved and are converted primarily to urea, which is excreted, while the carbon skeleton enters the citric acid cycle to be used as the energy source. When protein is used as an energy source, optimal protein synthesis cannot occur (Kashyap 1994). Consequently, protein intake needs to be evaluated in relation to energy intake for a direct comparison of alleged benefits and risks of higher protein intake.

Protein intake also needs to be evaluated in relation to intake of other nutrients, as differences in intake of other nutrients may influence infant growth rates (Castillo‐Duran 2003; Isojima 2015; Musoke 2001), and higher protein intakes may increase infant requirements for other nutrients, such as phosphate (Bonsante 2013). If studies provide variable amounts of protein and other nutrients at the same time, it is not possible to attribute study findings solely to the difference in protein intake. If formulas vary by more than 10% in any constituent other than protein, a direct comparison of outcomes may not be valid.

A related Cochrane Review concluded that protein supplementation of human milk in relatively well preterm infants offers certain short‐term benefits, including increases in weight gain, linear growth, and head growth (Amissah 2018). Although urea levels were higher among patients receiving protein supplementation, this was thought to reflect adequate rather than excessive dietary protein intake. Long‐term effects and adverse effects of protein supplementation of human milk could not be evaluated in this previous systematic review because of an absence of relevant data (Amissah 2018). The balance between supposed benefits and risks of higher protein intake for formula‐fed low birth weight infants weighing < 2.5 kilograms remains unclear.

Objectives

To determine whether higher (≥ 3.0 g/kg/d) versus lower (< 3.0 g/kg/d) protein intake during the initial hospital stay of formula‐fed preterm infants or low birth weight infants (< 2.5 kilograms) results in improved growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes without evidence of short‐ or long‐term morbidity.

Specific objectives were to examine the following comparisons of interventions and to conduct subgroup analyses if possible.

Low protein intake if the amount was less than 3.0 g/kg/d.

High protein intake if the amount was equal to or greater than 3.0 g/kg/d but less than 4.0 g/kg/d.

Very high protein intake if the amount was equal to or greater than 4.0 g/kg/d.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials and excluded quasi‐randomized trials.

Types of participants

We included infants who weighed less than 2.5 kilograms at birth, whether appropriate‐ or small‐for‐gestational‐age (AGA or SGA), who were studied during their initial hospital stay. They were exclusively fed formula and did not receive parenteral nutrition during the study.

Types of interventions

The interventions comprised different levels of protein intake during the initial hospital stay, which were categorized as follows: low protein intake if the amount was less than 3.0 g/kg/d, high protein intake if the amount was equal to or greater than 3.0 g/kg/d but less than 4.0 g/kg/d, and very high protein intake if the amount was equal to or greater than 4.0 g/kg/d. Contrasting levels of protein intake were compared over different periods of time.

Types of outcome measures

We used the criteria and standard methods of Cochrane and Cochrane Neonatal (see the Cochrane Neonatal search strategy for specialized register).

Primary outcomes

Growth parameters, including weight gain (g/kg/d or g/d), linear growth (cm/week), and head growth (cm/week), expressed in absolute terms or relative to intrauterine references or growth charts

Intelligence quotient (IQ) scores and Bayley score at 18 months and/or later

Necrotizing enterocolitis (Bell’s stage II or greater)

Secondary outcomes

Nitrogen utilization as reflected by blood urea (mmol/L)

Nitrogen accretion, expressed in absolute terms such as g/kg/d or relative to fetal accretion rate

Abnormal phenylalanine levels

Decreased gastric motility (number of episodes of abdominal distention experienced per day)

Days to full feedings (days from initiation of feedings to achievement of 120 mL/kg/d)

Feeding intolerance (number of feeding interruptions related to feeding intolerance experienced per day)

Metabolic acidosis (pH, base excess)

Serum albumin (g/L)

Sepsis (number of babies who developed confirmed sepsis‐positive blood culture and the organism[s] identified)

Diarrhea (number of babies who developed episodes of stools considered to have abnormal water loss)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted a comprehensive search that included the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 8), in the Cochrane Library (August 2, 2019); OVID MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) (January 1, 2013, to August 2, 2019); MEDLINE via PubMed (July 1, 2018, to August 2, 2019) for the previous year; and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; January 1, 2013, to August 2, 2019). See Appendix 1 for full search details. We did not apply language restrictions.

We searched clinical trial registries for ongoing and recently completed trials (ISRCTN Registry). We searched the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/), as well as the US National Library of Medicine ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov), via Cochrane CENTRAL.

This updates the searches that were completed for previous versions of this review (Appendix 2; Fenton 2014).

Searching other resources

We also searched the reference lists of any articles selected for inclusion in this review to identify additional relevant articles.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence.

Selection of studies

All articles retrieved from the complete search were assessed for relevance independently by two review authors (HA, TRF). We considered RCTs testing contrasting levels of formula protein intake during initial hospital stay if they met the following criteria for relevance.

Study participants weighed less than 2.5 kilograms at birth.

Study participants were not receiving parenteral nutrition at the time of randomization.

Study participants were exclusively formula‐fed.

Energy, Na, K, P, Zn, and essential fatty acid intakes did not differ significantly (by no more than 10% relative concentration).

Given the small number of trials that met all of these criteria, and some larger and important studies that met the first three but not the last criterion, the review authors decided to include these studies in a post‐facto analysis of the primary outcomes to provide readers with a more comprehensive and clinically relevant systematic review.

If all of the protein intake groups within a study fell inside one of the predesignated protein intake criteria, we excluded this study.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (HA, TRF) independently extracted data. We resolved differences by discussion and on the basis of consensus of three review authors. We made efforts to contact investigators for data, additional information, and/or clarification regarding 6 studies (Bhatia 1991; Embleton 2005; Hillman 1994; Kashyap 1986; Svenningsen 1982a; Wauben 1995).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (HA, TRF) independently assessed the risk of bias (low, high, or unclear) of all included trials using the Cochrane "Risk of bias" tool for the following domains (Higgins 2011).

Sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective reporting (reporting bias).

Any other bias.

We resolved any disagreements by discussion, or by consultation with a third assessor. See Appendix 3 for a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain.

Measures of treatment effect

We performed statistical analyses using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014). We analyzed categorical data using risk ratio (RR), risk difference (RD), and the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB). We analyzed continuous data using mean difference (MD) and standardized mean difference (SMD). We reported the 95% confidence interval (CI) for all estimates. We used a standardized statistical method to handle three‐arm trials in which two groups fell within one predesignated protein intake group (Rosner 2000).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participating infant in individually randomized trials, and an infant was considered only once in the analysis.

Dealing with missing data

When feasible, we carried out analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis for all outcomes. We requested missing data by contacting the original investigators. We will address the potential impact of missing data on the findings of the review in the Discussion section.

Assessment of heterogeneity

A statistical test for heterogeneity (I² test) included in the graphical output of Cochrane Reviews was used to assess variability in treatment effects evaluated by different trials.

We estimated the treatment effects of individual trials and examined heterogeneity among trials by inspecting the forest plots and quantifying the impact of heterogeneity using the I² statistic. We graded the degree of heterogeneity as follows: less than 25% no heterogeneity; 25% to 49% low heterogeneity; 50% to 75% moderate heterogeneity; more than 75% substantial heterogeneity. When we noted statistical heterogeneity (I² > 50%), we explored the possible causes (e.g. differences in study quality, participants, intervention regimens, or outcome assessments).

Assessment of reporting biases

We conducted a comprehensive search for eligible studies and were alert for duplication of data. Because we did not identify 10 or more trials for meta‐analysis, we did not assess for possible publication bias by inspecting a funnel plot.

Data synthesis

Because we identified multiple studies that we considered to be sufficiently similar, we performed meta‐analysis using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). For categorical outcomes, we calculated the typical estimates of RR and RD, each with its 95% CI; for continuous outcomes, we calculated the MD or the SMD, each with its 95% CI. We used a fixed‐effect model to combine data when it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect. When meta‐analysis was inappropriate, we analyzed and interpreted individual trials separately. When we found evidence of clinical heterogeneity, we tried to explain this based on the different study characteristics and subgroup analyses.

Certainty of evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the certainty of evidence of the following (clinically relevant) outcomes: weight gain (g/kg/d); linear growth (cm/week); head circumference growth (cm/week); IQ scores and Bayley score at 18 months or later; and necrotizing enterocolitis.

Two review authors (HA, TRF) independently assessed the certainty of evidence for each of the outcomes above. We considered evidence from RCTs as high certainty but downgraded the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations based upon the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of evidence, precision of estimates, and presence of publication bias. We used the GRADEpro GDT Guideline Development Tool to create three "Summary of findings" tables to report the certainty of evidence.

The GRADE approach results in an assessment of the certainty of a body of evidence according to one of four grades.

High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If the reviewed studies combined alterations of protein and energy, we planned to carry out subgroup analyses for the planned categories of protein intake according to the following predefined energy intake categories.

Low energy intake: less than 105 kcal/kg/d.

Medium energy intake: greater than or equal to 105 kcal/kg/d and less than or equal to 135 kcal/kg/d.

High energy intake: greater than 135 kcal/kg/d.

As the Ziegler‐Fomon reference fetus estimates different protein requirements for infants based on birth weight, we planned to undertake subgroup analyses for the following birth weight categories.

< 800 grams.

800 to 1199 grams.

1200 to 1799 grams.

1800 to 2499 grams.

Post‐facto analysis

We conducted a post‐facto analysis to examine the results from studies in which formulas fed to low birth weight infants differed in one or more other nutrients by more than 10%. These studies had been excluded from the primary analysis of this systematic review based on the a priori defined selection criteria for relevance because differences in outcome cannot be solely attributed to differences in protein.

Sensitivity analysis

When we identified substantial heterogeneity, we conducted sensitivity analysis to determine if the findings are affected by inclusion of only those trials considered to have used adequate methods with low risk of bias (selection and performance bias). We reported results of sensitivity analyses for primary outcomes only.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

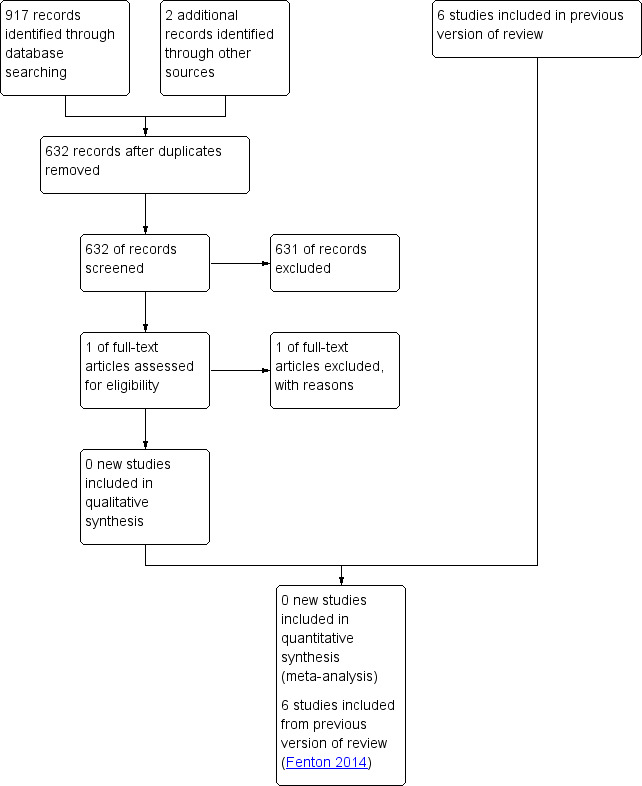

The original literature searches identified 49 studies, of which 13 were non‐randomized controlled studies (Fenton 2014). We did not identify additional studies for inclusion in the 2020 update of the review. We located one abstract; however, we did not include this study because both protein intakes fell within the same predesignated criterion of low protein intake (3.0 and 3.6 g/kg/d) (Cooke 2014). For a full description of our selection process, please see our "Study flow diagram" (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram, showing results of update search August 2, 2019.

We scrutinized a total of 34 randomized studies for criteria of relevance, of which 24 studies were excluded for the following reasons.

In eight studies, the protein intake groups fell inside one of the predesignated protein intake criteria.

In nine studies, the intervention being examined was different from that proposed in this systematic review (e.g. studies examining quality of protein).

In three studies, infants received parenteral nutrition during the study period.

Three studies reported no or incomplete numerical data.

In one study, the experimental protocol was modified during the study period.

Included studies

Studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria

We identified six eligible trials (Bhatia 1991; Embleton 2005; Hillman 1994; Kashyap 1986; Svenningsen 1982a; Wauben 1995), which enrolled a total of 218 low birth weight infants and met all inclusion criteria for the primary analysis of formulas that did not differ in nutrients other than protein. Details of studies that met the inclusion criteria are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Bhatia 1991 randomly assigned 23 AGA and SGA infants of birth weight less than 1550 grams to one of three formulas that were identical in composition, except for the protein content. Three infants were withdrawn from the study. Infants were given study formula when they were tolerating 60 kcal/kg/d of a standard preterm infant formula. The study formulas were continued for two weeks after intake reached 100 kcal/kg/d. Growth, biochemical parameters, necrotizing enterocolitis, and neonatal behavior were assessed. Data for two groups in the high protein category were combined in this review.

Embleton 2005 randomly assigned 77 AGA and SGA infants of gestational age less than 35 weeks and birth weight less than 1750 grams in two strata (< 1250 grams, 1250 to 1750 grams) to one of three study formulas. The study began when infants were tolerating ≥ 150 mL/kg/d of enteral intake for ≥ 48 hours and current weight was ≥ 1000 grams. Infants received the study formulas until term plus 12 weeks corrected age. Data for two groups in the high protein category were combined in this review, providing average intakes of 4.1 versus 3.6 g/kg/day protein intake. Growth, body composition, and biochemical parameters were assessed. Very high protein intake did not increase weight gain at discharge, at term, or at 12 weeks corrected age.

Hillman 1994 randomly assigned 27 infants weighing less than 1500 grams at birth in three weight group strata (< 1000 grams, 1000 to 1250 grams, 1250 to 1500 grams) to one of three study formulas before feedings were initiated in the first week of life. All infants completed two‐week and four‐week assessments of growth, biochemical parameters, and bone mineral content; however, 14 of the 27 infants were discharged before the six‐week assessment was performed. Data for two groups in the high protein category were combined in this review.

Kashyap 1986 randomly assigned 34 AGA and SGA low birth weight infants weighing 900 to 1750 grams at birth to receive one of three formulas. One group of nine infants received increased energy intake, so they were not included in this review. Growth, biochemical parameters, necrotizing enterocolitis, diarrhea, and nutrient balance were assessed. Data on energy expenditure and energy balance were collected for a subset of infants in this study and were published in Schulze 1987.

Svenningsen 1982a randomly allocated 48 AGA and SGA very low birth weight and preterm infants in the third week of life to one of three groups. One group received human milk and was not eligible for this review. The other two groups received formulas with or without the addition of a commercial product "protinpur" to produce high or low protein intake. Svenningsen 1982b reported long‐term follow‐up growth parameters and neurodevelopmental outcomes up to two years of age.

Wauben 1995 randomly allocated 16 healthy AGA preterm infants between 28 and 35 weeks gestational age to two formulas with differing protein content and conducted a modified three‐day protein and energy balance study. The study began once infants were receiving full enteral feedings of 160 mL/kg/d.

Studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients

Four studies (Cooke 2006; Goldman 1969; Kashyap 1988; Raiha 1976), which enrolled a total of 451 low birth weight infants fed formulas that differed in one or more other nutrients by more than 10%, were included in a post‐facto analysis for the primary outcomes. Details of studies included for the post‐facto analysis are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table.

In Cooke 2006, 18 preterm infants of birth weight ≤ 1500 grams and gestational age ≤ 32 weeks received both standard (3.0 g/100 kcal) and high protein (3.6 g/100 kcal) formulas over two one‐week comparison periods with the sequence of formula feeding randomly determined in a balanced cross‐over design. The higher protein formula had a 20% higher percentage of medium‐chain triglycerides (MCTs), 16% more sodium, 13% more potassium, 12% more chloride, 19% less copper, and 13% more magnesium compared with the standard protein formula. Anthropometry was performed at the beginning and at the end of each study period. Nutrient balance and plasma amino acids were determined at the end of each week.

Goldman 1969 randomly assigned 304 AGA and SGA infants of birth weight less than 2000 grams in three birthweight strata (< 1000 grams, 1000 to 1499 grams, and 1500 to 2000 grams) to two study formulas. Infants > 1000 grams were further stratified based on gender, and twins were assigned separately. Infants were followed from the first few days of life until 2200 grams was achieved. The study compared high (3.0 to 3.6 g/kg/d) versus very high (6.0 to 7.2 g/kg/d) protein intake. The higher protein formula had a 17% higher concentration of minerals. Growth and biochemical and neurological parameters were assessed. Two separate papers on the same study reported neurodevelopmental outcomes at three years and at five to seven years of age (Goldman 1971; Goldman 1974).

Kashyap 1988 randomly assigned 50 AGA and SGA low birth weight infants weighing 900 to 1750 grams at birth to receive one of three formulas until study end when the infants reached 2200 grams. One group of 15 infants who received increased energy intake was not included in this review. Formula in the high protein groups had 14% more potassium, 15% more calcium, and 20% more magnesium compared with formula in the low protein groups. Growth, biochemical parameters, necrotizing enterocolitis, and nutrient balance were assessed before study end when the infants reached 2200 grams.

Raiha 1976 randomly assigned 106 AGA infants of birth weight ≤ 2100 grams to one of four isocaloric formulas that varied in both quantity (2.25 and 4.5 g/kg/d) and type (whey:casein ratios) of protein in the first week of life. Infants were grouped into three categories: 28 to 30 weeks, 31 to 33 weeks, and 34 to 36 weeks. Potassium varied by 17%, calcium by 15%, and phosphorus by 12% in relative concentration in the whey predominant formulas between low and very high protein groups. Sodium varied by 28% and magnesium by 12% in relative concentration in the casein predominant formulas. Study formulas were provided until hospital discharge. Three separate published papers on this study have reported different outcomes (Gaull 1977; Rassin 1977a; Rassin 1977b).

Excluded studies

We excluded 24 studies. Details of reasons for exclusion are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Quality assessments are detailed in the Characteristics of included studies table and are summarized in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Infants were allocated to assigned treatment by randomization in all studies included in this updated review. Only two studies reported adequate concealment of allocation and blinding of randomization (Bhatia 1991; Embleton 2005).

Blinding

Seven studies reported that the intervention was blinded to caregivers, investigator(s), or both (Bhatia 1991; Cooke 2006; Embleton 2005; Goldman 1969; Kashyap 1986; Kashyap 1988; Raiha 1976). Six studies reported blinding of outcomes (Bhatia 1991; Cooke 2006; Embleton 2005; Kashyap 1986; Kashyap 1988; Raiha 1976).

Incomplete outcome data

Only one study reported a loss of more than 20% of study participants to attrition (Kashyap 1986), and six studies had smaller losses to follow‐up (Bhatia 1991; Embleton 2005; Goldman 1969; Hillman 1994; Kashyap 1988; Raiha 1976). Two studies reported no attrition (Cooke 2006; Wauben 1995), and one study was unclear about attrition (Svenningsen 1982a).

Selective reporting

Selective outcome reporting was not observed in any of the included studies.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other potential sources of bias in the reports. Only two studies reported an intention‐to‐treat analysis (Cooke 2006; Wauben 1995).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Comparison 1. High versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria)

See Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Growth parameters (Outcome 1.1)

Weight gain (g/kg/d) (Outcome 1.1.1)

Two studies found no significant differences in weight gain between groups (Bhatia 1991; Svenningsen 1982a). However, three studies found that infants receiving high protein intake had significantly greater weight gain (Hillman 1994; Kashyap 1986; Wauben 1995). The overall analysis revealed a significant difference in weight gain (mean difference [MD] 2.36 g/kg/d, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.31 to 3.40) in favor of the high protein group (low certainty). The evidence suggests that high versus low protein intake increases weight gain, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by risks of bias and heterogeneity.

Linear growth (cm/week) (Outcome 1.1.2)

Kashyap 1986 found that infants receiving high protein intake had significantly greater linear growth, and Svenningsen 1982a observed no significant differences between groups. The overall analysis did not reveal a significant difference (MD 0.16 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.34) (low certainty). The evidence suggests that high versus low protein intake probably leads to little or no difference in the rate of length gain, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by risks of bias and imprecision.

Head growth (cm/week) (Outcome 1.1.3)

Kashyap 1986 found that infants receiving high protein intake had significantly greater head growth. Three studies reported no significant differences in head growth (Bhatia 1991, Hillman 1994; Svenningsen 1982a). However, data were missing, so these three studies were not included in the meta‐analysis. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of protein on head circumference growth, and it may have little to no effect on head circumference growth, but the evidence is very uncertain (very low certainty).

IQ score and Bayley score at 18 months and/or later

No study primarily addressed these outcomes; however, two studies reported neurodevelopmental outcomes for infants enrolled in their studies (Bhatia 1991; Svenningsen 1982a).

Bhatia 1991 assessed behavior in a subset of 15 infants within five days of completing the feeding study. Infants were approximately 36 to 37 weeks at the time of testing. A certified child psychologist, blinded to the feeding history of the infants, administered the Neonatal Behavior Assessment Scale. Infants receiving formula with higher protein intake performed significantly better on the orientation (P = 0.0003), habituation (P = 0.003), and autonomic stability (P = 0.01) clusters of the Neonatal Behavior Assessment Scale. No differences between groups were noted in the remaining behavioral clusters of motor (P = 0.7), range of state (P = 0.5), and regulation of state (P = 0.29).

Svenningsen 1982a reported no significant differences in neurodevelopmental outcomes up to two years of age. Investigators assessed developmental performance indicators such as sitting, standing, walking, and talking at five to six, 10 to 11, 14 to 18, and 24 months of age for 46 of the 48 infants enrolled in the study. At 10 to 14 months, an audiometric test was also performed. The instruments used for these assessments were not identified.

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (Bell's stage II or greater) (Outcome 1.2.1)

Two studies reported no incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in high or low protein intake groups (Svenningsen 1982a; Wauben 1995). However, it is uncertain what criteria were used to define necrotizing enterocolitis in these studies. For the purpose of this systematic review, necrotizing enterocolitis was defined as Bell's stage II or greater. The overall analysis showed no significant effect of protein intake on necrotizing enterocolitis (typical risk difference [RD] 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.12) (very low certainty) (Analysis 1.2). High versus low protein intake may not increase necrotizing enterocolitis, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by risks of bias and by the small sample size.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: High versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria), Outcome 2: Necrotizing enterocolitis

Secondary outcomes

Decreased gastric motility (number of episodes of abdominal distention)

No study addressed this outcome.

Days to full feedings (from initiation of feedings to achievement of 120 mL/kg/d)

Kashyap 1986 defined full intake as 180 mL/kg/d, which was maintained throughout the study. No significant differences between groups were noted with respect to the age at which feedings were started and the age at which full feeding was attained. None of the other studies provided information on when full feedings were achieved.

Feeding intolerance (number of episodes per day)

No study addressed this outcome.

Nitrogen utilization

Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) (Outcome 1.3.1)

Three studies report higher blood urea nitrogen levels among infants receiving high protein intake (Bhatia 1991; Kashyap 1986; Svenningsen 1982a).

Svenningsen 1982a did not find a significant difference in blood urea nitrogen at the third and fifth weeks of life, although at seven weeks, levels were significantly higher among infants receiving higher protein intake (third week P = 0.85, fifth week P = 0.375, and seventh week P = 0.0005). Blood urea nitrogen levels were measured by Svenningsen 1982a at different time points than in the other studies, so this study was not included in the meta‐analysis.

When data from the two studies that measured blood urea nitrogen at the two‐week point were combined (Bhatia 1991; Kashyap 1986), significantly higher levels were noted in infants in the high protein intake group (weighted mean difference [WMD] 1.92 mg/dL, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.84) compared with the low protein intake group (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: High versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria), Outcome 3: Nitrogen utilization

Nitrogen balance

Nitrogen accretion (mg/kg/d) (Outcome 1.4.1)

Two studies reported statistically significantly higher protein accretion in the high protein formula groups (Kashyap 1986; Wauben 1995). The meta‐analysis revealed significantly higher nitrogen accretion (MD 143.7 mg/kg/d, 95% CI 128.7 to 158.8) in infants receiving formula with high protein content compared with infants given low protein formula (Analysis 1.4). Of note, significant heterogeneity of treatment effect was evident; consequently, these data should be interpreted prudently.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: High versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria), Outcome 4: Nitrogen balance

Phenylalanine levels

Plasma phenylalanine concentration (μmol/dL) (Outcome 1.5.1)

Bhatia 1991 and Kashyap 1986 tested phenylalanine levels and found no significant differences between low and high protein formula groups (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: High versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria), Outcome 5: Phenylalanine levels

Bhatia 1991 measured phenylalanine concentrations at the end of the two‐week study period. Kashyap 1986 monitored plasma amino acid concentrations before feedings were started, then weekly once the target intake was achieved. Different approaches were used to report data, so a meta‐analysis could not be undertaken.

Metabolic acidosis (pH, base excess) (Outcome 1.6)

Kashyap 1986 reported blood acid‐base status and found pH and base excess to be within normal limits for all infants enrolled in the study regardless of group assignment (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: High versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria), Outcome 6: Metabolic acidosis (pH, base excess)

Serum albumin (g/L) (Outcome 1.7)

Kashyap 1986 reported albumin as approximately 3 g/dL, and Hillman 1994 and Svenningsen 1982a reported albumin as 3 mg/dL and 30 g/mL, respectively (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: High versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria), Outcome 7: Serum albumin (g/L)

We attempted to clarify the units with the latter two study authors without success. Hillman 1994 measured albumin values at four and six weeks of age. Svenningsen 1982a measured albumin levels at approximately zero, two, and four weeks of the study. The values reported for each time period were not significantly different between low and high protein formula groups.

Kashyap 1986 reported prealbumin (mg/dL) (i.e. transthyretin) levels and found a significant difference between low and high protein formula groups, favoring the high protein formula group. A meta‐analysis could not be undertaken, given the discrepancy in the units used to report findings and the differences in time frames used to measure serum albumin.

Sepsis: incidence, number of episodes (Outcome 1.8)

Although Svenningsen 1982a reported no differences in rates of septicemia between groups, supporting data were not provided. Additionally, it is uncertain what constituted septicemia (e.g. positive blood culture, positive cerebrospinal fluid). Hillman 1994 indicated that five of the 27 infants enrolled in this study failed to complete at least four weeks of the study because the infants became unwell (e.g. sepsis), or because the infants were transferred to another hospital. The exact number of infants who developed infection was not specified (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: High versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria), Outcome 8: Sepsis

Diarrhea (number of episodes per day per baby) (Outcome 1.9)

Kashyap 1986 addressed the outcome of diarrhea using a categorical rather than a continuous level of measurement. Kashyap 1986 indicated that of seven infants withdrawn from the study (n = 34 infants), one developed diarrhea. This infant belonged in the group that differed in energy intake rather than protein intake and therefore was not included in this review (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: High versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria), Outcome 9: Diarrhea

Subgroup analyses

Stratification based on energy intake

No study addressed this outcome.

Distinction in birth weight categories

Although Hillman 1994 assigned infants enrolled in this study within three overlapping weight group strata (< 1000 grams, 1000 to 1250 grams, and 1250 to 1500 grams), data were not presented for each weight category but rather were based on protein group assignment. No other study reported data for birth weight categories. Consequently, subgroup analyses for birth weight categories were not undertaken.

Comparison 2. Very high versus low protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria)

No study addressed this outcome (Table 2).

Comparison 3. Very high versus high protein intake (restricted to studies meeting all a priori inclusion criteria)

See Table 3.

Primary outcomes

Growth parameters at discharge (Outcome 3.1)

Weight gain (g/d) (Outcome 3.1.1)

Embleton 2005 found that infants receiving very high protein intake compared with high protein intake showed no significant differences between groups in weight gain (g/d) to discharge (P = 0.053) (moderate certainty). The evidence suggests that very high protein intake, compared to high protein intake, increases weight gain, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by imprecision. This study of very high protein intake in the primary analysis provided average intakes of 4.1 versus 3.6 g/kg/day protein intake.

Linear growth (cm/week) (Outcome 3.1.2)

Embleton 2005 reported greater length gain from study enrollment to discharge; the confidence interval included both a possible difference and no important difference of 0.10 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.20) (P = 0.044) (moderate certainty). Very high protein intake (compared to high protein intake) may have little or no effect on the rate of length gain, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by imprecision.

Head growth (cm/week)

No study addressed this outcome.

Growth parameters at term (Outcome 3.2)

Weight gain (g/d) (Outcome 3.2.1)

Embleton 2005 detected no differences in weight gain between infants receiving very high protein intake and those with high protein intake from study enrollment until term (P = 0.2).

Linear growth (cm/week) (Outcome 3.2.2)

Embleton 2005 found no differences in length growth from study enrollment until term (P = 1.0).

Head growth (cm/week)

No study addressed this outcome.

Growth parameters at 12 weeks corrected age (Outcome 3.3)

Weight gain (g/d) (Outcome 3.3.1)

Embleton 2005 observed no significant differences in weight gain between groups receiving study formula between the time of discharge and term plus 12 weeks corrected age (P = 0.88).

Linear growth (cm/week) (Outcome 3.3.2)

Embleton 2005 found no significant differences in linear growth between groups receiving study formula between the time of discharge and term plus 12 weeks corrected age.

Head growth (cm/week)

No study addressed this outcome.

IQ score and Bayley score at 18 months and/or later

No study addressed this outcome.

Nectrotizing enterocolitis (Bell's stage II or greater)

No study addressed this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Nitrogen utilization

Blood urea nitrogen (mM)

Embleton 2005 tested serum for urea nitrogen levels (mM) and found that three of the 24 infants receiving very high protein intake developed uremia, defined as serum urea nitrogen level greater than 6 mM. Increase in serum urea nitrogen levels was associated with the level of protein intake; levels normalized without intervention within two to three days in two infants, and within 10 days in another infant. As data were not reported, it was not feasible to determine whether group differences were significant when groups with high protein intake were combined.

Nitrogen balance

Nitrogen accretion (mg/kg/d)

No study addressed this outcome.

Phenylalanine levels

Plasma phenylalanine concentration (μmol/dL)

No study addressed this outcome.

Decreased gastric motility (number of episodes of abdominal distention)

No study addressed this outcome.

Days to full feedings (from initiation of feedings to achievement of 120 mL/kg/d)

Embleton 2005 did not define full feedings. No significant differences between the three groups were noted with respect to the age at which feedings were started nor the age at which full feeding was attained. As data were skewed, median and range were reported; it was not feasible to combine data for the groups representing high protein intake nor to compare them with data for the groups representing very high protein intake.

Feeding intolerance (number of episodes per day)

No study addressed this outcome.

Metabolic acidosis (pH, base excess)

Embleton 2005 reported acid‐base status within normal limits for infants in the very high protein intake group who developed uremia (i.e. serum blood urea nitrogen levels > 6 mM).

Serum albumin (g/L)

Embleton 2005 reported no significant differences in total albumin among infants in the three groups. As data were not reported, it is not feasible to combine data for the groups representing high protein intake nor to compare them with data for the groups representing very high protein intake.

Sepsis: incidence, number of episodes

No study addressed this outcome.

Diarrhea (number of episodes per day per baby)

No study addressed this outcome.

Subgroup analysis

Stratification based on energy intake

No study addressed this outcome.

Distinction in birth weight categories

Although Embleton 2005 stratified infants enrolled in this study into two birth weight categories (< 1250 grams and 1250 to 1750 grams), data were not presented for each weight category but rather were based on protein group assignment. Consequently, subgroup analyses for birth weight categories were not undertaken.

Post‐facto analysis

Comparison 4. High versus low protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients)

Primary outcomes

Growth parameters (Outcome 4.1)

Weight gain (g/kg/d) (Outcome 4.1.1)

Kashyap 1988 found weight gain to be significantly lower in the low protein intake formula group. Inclusion of this study in the overall analysis revealed improvement in weight gain (MD 2.53 g/kg/d, 95% CI 1.62 to 3.45) beyond that revealed in the a priori analysis among infants receiving formula with high protein content (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: High versus low protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 1: Growth parameters

Linear growth (cm/week) (Outcome 4.1.2)

Two studies found no significant differences in linear growth between groups (Kashyap 1988; Svenningsen 1982a). These findings differed from those of Kashyap 1986, which noted a significant increase in linear growth among infants receiving higher protein intake. Inclusion of the Kashyap 1988 study in the meta‐analysis revealed a significant difference (MD 0.16 cm/week, 95% 0.03 to 0.30) and greater linear growth with high protein intake compared with low protein intake (Analysis 4.1).

Head growth (cm/week) (Outcome 4.1.3)

Kashyap 1988 found that infants receiving high protein intake had significantly greater head growth (P = 0.027). With inclusion of this study, a meta‐analysis revealed significantly greater head growth among those in the high protein intake group (MD 0.23 cm/week, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.35) compared with those in the low protein intake group (Analysis 4.1).

IQ score and Bayley score at 18 months and/or later

No study addressed this outcome.

Nectrotizing enterocolitis (Bell's stage II or greater)

No study addressed this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Nitrogen utilization (Outcome 4.2)

Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) (Outcome 4.2.1)

Kashyap 1988 found significantly higher blood urea nitrogen levels with increased protein intake. These findings are consistent with those of Bhatia 1991 and Svenningsen 1982a. Kashyap 1986 reported low levels of blood urea nitrogen in all groups, but levels were significantly lower in the low protein group. As both Kashyap 1986 and Kashyap 1988 reported results that were measured weekly, a meta‐analysis was possible for both of these studies. A significant increase in blood urea nitrogen levels was evident in the high protein intake group (MD 3.22 mg/dL, 95% CI 2.48 to 3.96). Of note, significant heterogeneity of treatment effect was evident; consequently, the data should be interpreted with caution (Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4: High versus low protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 2: Nitrogen utilization

Nitrogen balance (Outcome 4.3)

Nitrogen accretion (mg/kg/d) (Outcome 4.3.1)

Kashyap 1988 found that protein intake exerted a positive effect on nitrogen retention. These findings are consistent with those of Kashyap 1986 and Wauben 1995. With inclusion of this study, the meta‐analysis continued to show significantly higher nitrogen accretion (MD 112.6 mg/kg/d, 95% CI 101.4 to 123.8) in infants receiving formula with higher protein content (Analysis 4.3). Significant heterogeneity of treatment effect was evident; consequently, the data should be interpreted with caution.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4: High versus low protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 3: Nitrogen balance

Phenylalanine levels (Outcome 4.4)

Plasma phenylalanine concentration (μmol/dL) (Outcome 4.4.1)

Kashyap 1988 found no significant difference in concentrations of plasma phenylalanine between infants fed high versus low protein intake. When data from this study were included with those of Kashyap 1986, the meta‐analysis showed no significant difference (MD 0.25 μmol/dL, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.70) in concentrations of plasma phenylalanine between groups (Analysis 4.4).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4: High versus low protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 4: Phenylalanine levels

Additional secondary outcomes:

No study reported results for the following outcomes: decreased gastric motility, days to full enteral feedings, feeding intolerance, metabolic acidosis, serum albumin, sepsis, or diarrhea.

Comparison 5. Very high versus low protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients)

Primary outcomes

Weight gain (g/week) (Outcome 5.1)

Raiha 1976 reported rate of weight gain in g/week measured from the time birth weight was regained to 2400 grams based on gestational age category. No significant differences in the rate of weight gain were noted between low and very high protein intake groups of any gestational age (Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Very high versus low protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 1: Weight gain (g/week)

Linear growth (cm/week) (Outcome 5.2)

Raiha 1976 reported rate of growth in crown‐rump length (cm/week) from regaining birth weight to attaining 2400 grams based on gestational age category. No significant differences were noted between low and very high protein intake groups in any gestational age strata (Analysis 5.2).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Very high versus low protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 2: Linear growth (cm/week)

Head growth (cm/week)

Raiha 1976 reported no significant difference in the rate of growth of head circumference from regaining birth weight to 2400 grams between low and very high protein intake groups of any gestational age. No numerical data were documented.

IQ score and Bayley score at 18 months and/or later

No study addressed this outcome.

Nectrotizing enterocolitis (Bell's stage II or greater)

No study addressed this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Nitrogen utilization

Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL)

Raiha 1976 reported a significant difference in blood urea nitrogen levels between infants fed very high versus low protein formulas when data from the three gestational ages were combined. Blood urea nitrogen levels varied directly with the quantity of protein in the diet; levels were greater than the normal range in infants receiving very high protein intake. Investigators report progressive elevation in blood urea nitrogen levels and metabolic acidosis in two infants receiving very high protein intake ‐ one given whey predominant formula (5%) and one given casein predominant formula (5%). Graphical data rather than numerical values were presented.

Nitrogen balance

Nitrogen accretion (mg/kg/d)

No study addressed this outcome.

Phenylalanine levels (Outcome 5.3)

Plasma phenylalanine concentration (μmol/dL) (Outcome 5.2.1)

Raiha 1976 found that infants fed formula providing higher protein intake had higher concentrations of plasma phenylalanine, particularly infants fed the casein predominant formula, when data from the three gestational ages were combined.

Additional secondary outcomes:

No study reported results for the following outcomes: decreased gastric motility, days to full enteral feedings, feeding intolerance, metabolic acidosis, serum albumin, sepsis, or diarrhea.

Comparison 6. Very high versus high protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients)

Primary outcomes

Growth parameters(Outcome 6.1)

Weight gain (g/kg/d) (Outcome 6.1.1)

Cooke 2006 reported significantly higher weight gain in the very high protein formula group compared with the high protein group (23.1 ± 7 versus 16.7 ± 6 g/kg/d, P = 0.04). Goldman 1969 did not report weight gain (g/kg/d) but rather the number of days from regaining birth weight to 2200 grams. Based on regression curves calculated for infants < 1500 grams and > 1500 grams, more infants in the very high protein intake group took longer than the calculated period of time to reach 2200 grams (P < 0.01).

Weight gain (g/d) (Outcome 6.1.2)

In the analysis of weight gain in g/d, when the results of Cooke 2006 and Embleton 2005 were combined, weight gain was greater in the very high protein formula group (MD 3.9 g/d, 95% CI 1.04 to 6.77).

Linear growth (cm/week)

No study addressed this outcome.

Head growth (cm/week)

No study addressed this outcome.

IQ score or Bayley score at 18 months and/or later (Outcomes 6.2 and 6.3)

Two separate papers on the Goldman 1969 study reported incidences of low Stanford‐Binet test scores in infants at three years and five to seven years of life, respectively (Goldman 1971; Goldman 1974). Of the 80% of infants from the original study who were assessed at three years (corrected age and chronological age), a similar incidence of IQ scores below 90 was observed among infants fed very high and high protein formulas. Of the 81% of infants from the original study who were assessed at five to seven years, a similar incidence of IQ scores below 90 was reported in both groups. At both the three‐year evaluation and the five‐ to seven‐year evaluation, a significantly higher incidence of IQ scores below 90 was reported among infants of birth weight less than 1300 grams who received very high protein intake compared with those fed high protein intake (Analysis 6.2; Analysis 6.3).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Very high versus high protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 2: Low IQ or Bayley score at 18 months and/or later (all infants)

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Very high versus high protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 3: Low IQ or Bayley score at 18 months and/or later (in infants < 1300 grams)

Secondary outcomes

Nitrogen utilization (Outcome 6.4)

Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) (Outcome 6.4.1)

Cooke 2006 reported a significantly higher blood urea level in the very high protein formula group compared with the high protein group (MD 1.4 mg/dL, 95% CI 0.4 to 2.4) (Analysis 6.4).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Very high versus high protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 4: Nitrogen utilization

Nitrogen balance (Outcome 6.5)

Nitrogen accretion (mg/kg/d) (Outcome 6.5.1)

Cooke 2006 found significantly higher nitrogen accretion in infants fed the very high protein formula (MD 88 mg/kg/d, 95% CI 25.17 to 150.83) (Analysis 6.5).

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Very high versus high protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 5: Nitrogen balance

Phenylalanine levels (Outcome 6.6)

Plasma phenylalanine concentration (μmol/dL) (Outcome 6.6.1)

Cooke 2006 reported a non‐significantly higher plasma phenylalanine concentration in infants fed very high protein formula (MD 0.3 μmol/dL, 95% CI ‐0.67 to 1.27) (Analysis 6.6).

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Very high versus high protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 6: Phenylalanine levels

Metabolic acidosis (mEq/L) (Outcome 6.7)

Cooke 2006 found no significant difference in base excess between the two groups (MD 0.5 mEq/L, 95% CI ‐1.19 to 2.19) (Analysis 6.7).

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Very high versus high protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 7: Metabolic acidosis (base excess)

Serum albumin (g/L) (Outcome 6.8)

Cooke 2006 reported serum albumin levels and found no significant differences between the two groups (31 ± 3 versus 31 ± 3 g/L) (Analysis 6.8).

6.8. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Very high versus high protein intake (adding studies comparing formulas with differences in other nutrients), Outcome 8: Serum albumin (g/L)

Additional secondary outcomes:

No study reported results for the following outcomes: decreased gastric motility, days to full enteral feedings, feeding intolerance, sepsis, or diarrhea.

Discussion

Although a large number of studies (n = 41) were identified, upon close inspection only six studies were found to be suitable for inclusion in this systematic review (Bhatia 1991; Embleton 2005 [partial data]; Hillman 1994; Kashyap 1986; Svenningsen 1982a; Wauben 1995). The trials were small, and all except one had methodological limitations; the most frequent uncertainty was about incomplete outcome data. Most studies were excluded because they did not compare sufficiently different protein intakes, or because they examined a different intervention (e.g. studies examining quality of protein). Methodological limitations of the included trials may have introduced bias and therefore pose a threat to the validity of the analysis as follows.

Only two studies had adequately concealed allocation (Bhatia 1991; Embleton 2005).

Differences in protein content among comparison groups in some of the individual trials may be too small (range 0.56 to 1.36 g/kg/d) to illustrate the potential effects of changes in protein intake.

Formulas in some studies differed substantially across interventions.

The duration of interventions and/or study periods varied from eight days in Wauben 1995 to two years in Svenningsen 1982a.

Characteristics of participants varied across studies, with some studies including healthier and more mature preterm infants.

Researchers did not define which calculation of g/kg/day growth velocity they used (Fenton 2019).

These limitations may explain some of the differences in treatment effects and the statistical heterogeneity evident in trial outcomes.

For this review to be comprehensive and more clinically relevant, studies that varied in nutrient content other than protein were included only in a post‐facto analysis. Four studies were considered in the post‐facto analysis (Cooke 2006; Goldman 1969; Kashyap 1988; Raiha 1976), although only two of these studies could be included in the meta‐analysis (Cooke 2006; Kashyap 1988).

Weight gain (g/kg/d) was the most commonly reported outcome. An overall increase in weight gain was reported in infants randomly assigned to the high protein intake group compared with those in the low protein intake group (mean difference [MD] 2.36 g/kg/d, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.31 to 3.40 for the overall analysis [low certainty]; MD 2.53 g/kg/d, 95% CI 1.62 to 3.45 for the post‐facto analysis). Certainty was downgraded one level for risk of bias (selection, performance, detection, attrition) and one level for inconsistency (I² = 57%).

One study that compared high (3.0 to 4.0 g/kg/d) versus very high (> 4 g/kg/d) protein intake (average intakes were 3.6 and 4.1 g/kg/d) during and after an initial hospital stay (n = 77) provided moderate‐certainty evidence showing no significant difference in weight gain (MD 3.10 g/d, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 6.24; P = 0.053) nor length gain (MD 0.0 cm/week, 95% CI ‐0.14 lower to 0.14; P = 1.0) to discharge from very high protein intake (4.1 versus 3.6 g/kg/d). This study also did not observe differences in weight or length gain to term and at 12 weeks corrected age with higher protein intakes. Three of the 24 infants receiving very high protein intake developed uremia. It is not known whether lack of a significant difference was due to insufficient differences in protein content between comparison groups (0.48 g/kg/d), or whether protein intakes > 4.0 g/kg/d do not support higher growth.

The most desirable level of protein intake is that which contributes to infant growth at the infant's predetermined genetic potential without negative consequences. The ideal composition of weight gain for the preterm infant is not known. It is generally considered that the lower lean tissue and higher fat gain of these infants relative to the fetus may not be desirable (Schulze 1987); however increasing evidence reveals that preterm infants do not have higher body fat compared to term‐born infants by three months corrected age (Goswami 2016; Griffin 2012; Scheurer 2017; Villela 2018). Significantly greater nitrogen accretion (MD 143.7 mg/kg/d, 95% CI 128.7 to 158.8 for the overall analysis; MD 112.6 mg/kg/d, 95% CI 101.4 to 123.8 for the post‐facto analysis) was observed in infants randomly assigned to the high protein intake groups. This greater nitrogen accretion suggests that some or all of the increment in weight is due to gains in lean body mass. These findings indicate that higher protein intake may help correct the non‐optimal body composition seen in preterm infants at term adjusted age (Gianni 2015; Villela 2018). Statistical heterogeneity was noted in nitrogen accretion; hence the data should be interpreted cautiously. Potential sources of heterogeneity might include clinical diversity (e.g. variability in participants, interventions, and outcome measures) and methodological variability (e.g. differences in trial design).

Two studies attempted to determine whether utilization of protein was enhanced by higher energy intake (Kashyap 1986; Kashyap 1988). These studies compared medium energy intake (120 kcal/kg/d) versus high energy intake (142 kcal/kg/d). Kashyap 1986 found that higher energy intake did not enhance protein utilization. This was evident in the similarities noted between groups in quantities of nitrogen retention, albumin, and prealbumin, as well as in the concentrations of blood urea nitrogen and most plasma amino acids. In contrast, in a later study, Kashyap 1988 reported improvements in nitrogen retention and blood urea nitrogen levels with higher energy intake.

Three studies reported that blood urea nitrogen levels were higher among infants fed high protein intake compared with those fed low protein intake (Bhatia 1991; Kashyap 1986; Svenningsen 1982a). Although detectable, some of these differences may not be clinically important. Three studies reported no significant differences in phenylalanine levels between low and high protein intake groups (Bhatia 1991; Kashyap 1986; Kashyap 1988). Inclusion of the two Kashyap studies in the post‐facto meta‐analysis resulted in no significant difference (MD 0.25, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.75) in concentrations of plasma phenylalanine between high and low protein intake groups.

Although the two Kashyap studies reported acid‐base status within normal limits (Kashyap 1986; Kashyap 1988), other trials raised concerns regarding metabolic acidosis among infants receiving high protein intake (Raiha 1976; Svenningsen 1982a). Raiha 1976 noted that infants receiving very high protein intake (4.5 g/kg/d) developed metabolic acidosis that resolved once infants were removed from the study and were fed breast milk. In the Svenningsen 1982a study, late metabolic acidosis occurred in 25% and 7%, respectively, of infants in high and low protein intake groups. It is possible that the supplement "protinpur" that was added to the low protein formula to prepare the high protein formula had poor biological value.

Very high protein intake may be poorly tolerated in infants with very low birth weight and extreme prematurity. Studies have not adequately evaluated short‐ and long‐term adverse sequelae of very high protein intake (≥ 4 g/kg/d). The single study of very high protein intake in the primary analysis reported an average protein intake of 4.1 versus 3.6 g/kg/day in its comparison arms (Embleton 2005). The maximal utilizable protein limits for infants in different weight and gestational age categories are unknown. In recent years, preterm infant formulas used in North America have changed such that if infants are fed at energy intake that exceeds 133 kcal/kg/d, protein intake will exceed 4 g/kg/d. In this systematic review, only one study compared high (≥ 3.0 g/kg/d but < 4.0 g/kg/d) versus very high protein intake (≥ 4.0 g/kg/d) both during and after initial hospital stay (Embleton 2005). Very high protein intake promoted significantly higher weights and lengths at discharge; weight gain to discharge was not significantly different (MD 3.10 g/kg/d, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 6.24), and differences in size did not remain significant at 12 weeks corrected age. Evidence suggests that very high protein intake, compared to high protein intake, increases weight gain, but our confidence in the effect estimate is limited by imprecision. Certainty was downgraded one level for imprecision (moderate certainty). Three of the 24 infants receiving very high protein intake developed uremia, which was associated with the level of protein intake and was normalized without intervention within two to three days in two infants, and within 10 days in another infant. Three studies in the post‐facto analysis assessed protein intake above 4.0 g/kg/d (Cooke 2006; Goldman 1969; Raiha 1976). The quantity of protein intake in these studies was 4.6 g/kg/d (Cooke 2006), 6 to 7.2 g/kg/d (Goldman 1969), and 4.5 g/kg/d (Raiha 1976). The findings of two studies could not be included in the meta‐analysis (Goldman 1969; Raiha 1976), as comparisons made within these studies were unique. A post‐facto meta‐analysis of two studies demonstrated significantly greater weight gain in the very high protein group compared with the high protein group (MD 3.9 g/d, 95% CI 1.04 to 6.77) (Cooke 2006; Embleton 2005).