Abstract

Background

During the outbreak of COVID-19, the national policy of home quarantine may affect the mental health of parents. However, few studies have investigated the mental health of parents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aims

To investigate the depression, anxiety and stress of the students’ parents during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to explore the influence factors, especially the influence of social support and family-related factors.

Methods

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Perceived Stress Scale-10 and Social Support Rating Scale were applied to 1163 parents to measure the parents’ depression, anxiety, stress and social support.

Results

(1) The detection rates of depression and anxiety in parents were 6.1% and 4.0%. The depression, anxiety and perceived stress of parents in central China were significantly higher than those in non-central China. The anxiety of college students’ parents was lower than that of parents of the primary, middle and high school students. The depression, anxiety and perceived stress of parents with conflicts in the family were significantly higher than those with a harmonious family. Other factors that influence parents’ depression, anxiety and perceived stress include marital satisfaction, social support, parents’ history of mental illness and parenting style, etc. (2) The regression analysis results showed that perceived stress, social support, marital satisfaction, family conflicts, child’s learning stage as well as parents’ history of mental illness had significant effects on parents’ anxiety and depression.

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the mental health of parents was affected by a variety of factors. Good marital relationships, good social support, family harmony and parents without a history of mental illness may be protective factors for parents’ mental health, while perceived stress and child in middle or high school are risk factors for parents’ mental health.

Keywords: parents, depression, anxiety, mental health

Introduction

COVID-19 broke out in China and became a worldwide threat in just a few months. In addition to threatening people’s physical health, COVID-19 brought great stress to the public and affected people’s mental health.

In the past, many studies have proven that individuals have strong stress responses in natural disasters or crises.1 In a large sample survey conducted nationwide recently, 35% of the public experienced psychological distress during the outbreak of COVID-19.2 The stress response caused by such public health events is generally manifested as anxiety and depression,3 and studies have shown that risk of depression and anxiety increases when people are in a state of long-term stress.4 5 Confirmed and suspected patients can also face long-term psychological problems after they are cured.6 Social support, as a supportive resource obtained by individuals from others or the society, is an important factor affecting individual mental health and can help individuals cope with the crisis in life.7 As a regulator, social support had an important effect on the stress response during severe acute respiratory syndrome.8 A recent study has shown that social support plays a moderating role between the public’s acute stress and anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic.9

Few studies have focused on the mental health of students’ parents. Since COVID-19 is highly infectious, and there is still a lack of effective treatment means, the core of prevention is to reduce the crowd gathering. In the leadership of the central policy, people began a long period of home quarantine, parents and children have to work and study at home. Parents and children are confined to limited space. In an online consultation during the COVID-19 pandemic, parents asked many practical problems such as how to get along with children and how to deal with the conflicts with children. Many parents participate in the relevant network lectures to improve communication with children, ease the family’s parent-child conflicts and improve the quality of the parent-child relationship. In addition to the stress caused by the pandemic, the parent-child relationship and the relationship between parents also affect the mental health of parents in such a difficult period, and parents’ mental health can further affect children’s mental and physical health, creating a vicious circle. Therefore, there is an urgent need to pay attention to the mental health of parents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, this study investigated the mental health of students’ parents and its influence factors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Participants

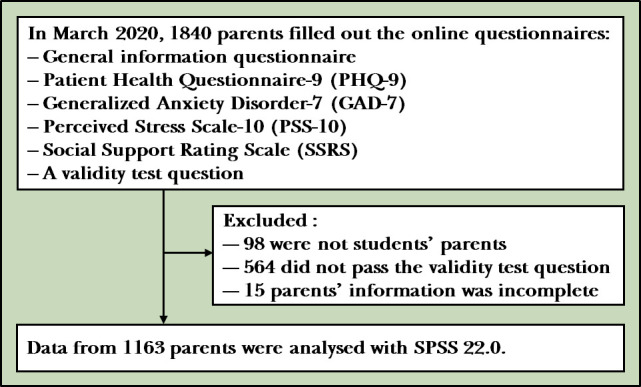

Researchers sent online questionnaires to parents of students from primary school to college in mid-March 2020. Participants were selected by purposive sampling. The participants were the primary caregivers of students and all parents volunteered to fill out the questionnaire. To ensure the quality of the questionnaires, a validity test question was set in the questionnaire, which was used to check whether the parents read the questions carefully. The validity test question requires participants to choose the fourth option. The parents who did not pass the validity test were excluded. A total of 1840 parents filled in the questionnaires, among which 98 participants were not the parents of the students, 564 participants failed the validity test question and the information of 15 parents was incomplete. In the end, 1163 valid questionnaires were obtained. The flowchart of the study is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study.

Measures

Demographic information questionnaire: the self-designed demographic information questionnaire was used to collect 15 items of information, including age, gender, domicile, years of education, child's learning stage, marital status, occupation, marital satisfaction (0–100), intimacy with child (0–100), economic level of family, parents’ history of mental illness, per capita housing area, parenting style, whether the parents or their family members had been quarantined for 2 weeks and whether there were family conflicts during the pandemic.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) 10: it is a brief screening scale for depression that measures the depressive symptoms of individuals in the past 2 weeks. It contains nine items, and each item is rated from 0 to 3; the total scores range from 0 to 27. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms, 0–4 indicates no depressive symptoms, 5–9 indicates mild depressive symptoms, 10–14 indicates moderate depressive symptoms and 15 or above indicates severe depressive symptoms. The Chinese version of the scale has good reliability and validity.11 In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.85.

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) 12: it is a screening scale for generalised anxiety disorder that measures the anxiety symptoms of individuals in the past 2 weeks. It contains seven items, and each item is rated from 0 to 3, and the total scores range from 0 to 21. Higher scores indicate more severe symptoms; 0–4 indicates no anxiety symptoms, 5–9 indicates mild anxiety symptoms, 10–14 indicates moderate anxiety symptoms and 15 or above indicates severe anxiety symptoms. The Chinese version of the scale has good reliability and validity.13 In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.91.

Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10) 14: it is used to evaluate an individual’s feeling of uncontrollable stress or an overload of stress, including two dimensions of negative feeling and positive feeling. It contains 10 items, and each item is rated from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate higher levels of stress. The Chinese version of the scale has good reliability and validity.15 In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.74.

Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS): it is used to measure the support of individuals from others or society. The scale consists of 10 items, which are divided into three dimensions: objective support, subjective support and utilisation of support. The scale has good reliability and validity.16 In this study, the Cronbach’s α was 0.85.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was done by using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS V.22.0). For skewed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann-Whitney U test were used for the single-factor test. For normal data, the one-way analysis of variance was used for the test with controls for age and years of education. The relationship between depression, anxiety, stress and various factors was analysed by using Spearman’s correlation. Ordinal regression was used to investigate the influence of multiple factors on depression and anxiety. P value < 0.05 was considered at the significant level.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 1163 valid questionnaires were collected, including 230 males (19.8%) and 933 females (80.2%). Parents’ domiciles were divided into two types: central China and non-central China. Central China includes Hubei, Hunan, Henan and Jiangxi. These provinces are geographically closer to the area where COVID-19 emerged (Wuhan) and were affected by the pandemic more severely. Non-central China includes the other regions of China. There were 162 parents (13.9%) from central China and 1001 parents (86.1%) from non-central China. There were 299 parents of primary school students (25.7%), 354 parents of middle school students (30.4%), 307 parents of high school students (26.4%) and 203 parents of college students (17.5%). There were 1098 parents of married or remarried (94.4%) and 65 divorced or widowed parents (5.6%). Most of the parents were clerks (39.9%) and professional and technical workers (25.7%). One hundred forty-six parents (12.5%) themselves or their family members had been quarantined for 2 weeks. Eight percent of the parents had a history of mental illness; 72.8% of parents had a medium or high economic level. Most parents had a permissive parenting style (63.5%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information of parents

| Variables | Frequency (%) | |

| Gender | Male | 230 (19.8%) |

| Female | 933 (80.2%) | |

| Domicile | Central China | 162 (13.9%) |

| Non-central China | 1001 (86.1%) | |

| Marital status | Married or remarried | 1098 (94.4%) |

| Divorced or widowed | 65 (5.6%) | |

| Occupation | Workers | 70 (6.0%) |

| Clerks | 464 (39.9%) | |

| Civil servants | 75 (6.4%) | |

| Professional and technical workers | 299 (25.7%) | |

| Farmers | 24 (2.1%) | |

| Self-employed | 136 (11.7%) | |

| Unemployed | 95 (8.2%) | |

| Quarantine | Parents themselves or their family members had been quarantined | 145 (12.5%) |

| No family members had been quarantined | 1018 (87.5%) | |

| Parents’ history of mental illness | No history of mental illness | 1070 (92%) |

| Having a history of mental illness | 93 (8.0%) | |

| Family economic level | Low | 316 (27.2%) |

| Medium or high | 847 (72.8%) | |

| Child's learning stage | Primary school | 299 (25.7%) |

| Middle school | 354 (30.4%) | |

| High school | 307 (26.4%) | |

| College | 203 (17.5%) | |

| Family conflicts | No conflicts | 928 (79.8%) |

| Having conflicts | 235 (20.2%) | |

| Parenting style | Authoritative | 329 (28.3%) |

| Authoritarian | 53 (4.6%) | |

| Permissive | 739 (63.5%) | |

| Uninvolved | 42 (3.6%) | |

General condition of parents’ anxiety, depression and stress

Based on PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores, depression and anxiety symptoms were divided into four levels, with 0–4 indicating no symptoms, 5–9 indicating mild symptoms of depression and anxiety, 10–14 indicating moderate symptoms and 15 or above indicating severe symptoms. Among the parents, mild depressive symptoms accounted for 27.3%, moderate depressive symptoms accounted for 4.6% and severe depressive symptoms accounted for 1.5%; mild anxiety symptoms accounted for 20.7%, moderate anxiety symptoms accounted for 3.4% and severe anxiety symptoms accounted for 0.5%. A score of 10 on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales was used as the dividing line for depression and anxiety. The detection rates of depression and anxiety were 6.1% and 4.0%. The detection rates of depression among parents of primary school, middle school, high school and college students were 8.4%, 5.6%, 5.2% and 4.4%, and the anxiety detection rates were 3.7%, 4.8%, 4.5% and 2.0%, respectively. The detection rates of depression among parents of central China and non-central China were 6.8% and 5.9%, and the anxiety detection rates were 5.6% and 3.7%, respectively.

Univariate analysis

The total scores of PHQ-9, GAD-7, PSS-10 and SSRS were taken as dependent variables for single-factor analysis. The results showed that there were no significant differences in the levels of depression, anxiety and stress in parents of different genders. The depression and anxiety of parents in central China were significantly higher than those in non-central China (Z=−2.534, p=0.011; Z=−3.017, p=0.003). There were no statistically significant differences in depression, anxiety and stress in parents of different marital status. Married or remarried parents had significantly higher levels of social support than divorced or widowed parents (F=52.873, p<0.001). The social support of parents in different occupations was significantly different (F=2.520, p=0.020), among which the social support of civil servants was the highest, significantly higher than that of unemployed parents. Parents who had been quarantined or whose family members had been quarantined had higher levels of depression than those who had no family members quarantined (Z=−2.379, p=0.017). Parents with a history of mental illness had significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress than parents without a history of mental illness (Z=−7.820, p<0.001; Z=−9.050, p<0.001; F=48.080, p<0.001), and the social support of parents with a history of mental illness was significantly lower than those without a history of mental illness (F=24.721, p<0.001).

The depression, anxiety and stress of parents with medium or high family economic level were significantly lower than those with low family economic level (Z=−4.012, p<0.001; Z=−2.166, p=0.030; F=16.746, p<0.001), and the social support of parents with medium or high family economic level were significantly higher than those with low family economic level (F=22.761, p<0.001). There were significant differences in depression, anxiety and social support among the parents of students in different learning stages (χ2=24.428, p<0.001; χ2=24.036, p<0.001; F=11.981, p<0.001). Bonferroni post hoc comparisons found that the anxiety and depression of college students’ parents were significantly lower than that of the parents of students in primary, middle and high school (p=0.012, p=0.001, p<0.001; p=0.001, p=0.001, p<0.001), and the social support of the parents of students in college students was significantly higher than that of other parents (p<0.001, p=0.002, p<0.001).

The depression, anxiety, stress and social support of parents with family conflicts were significantly different from those with a harmonious family (Z=−10.849, p<0.001; Z=−11.465, p<0.001; F=81.861, p<0.001; F=45.826, p<0.001). Marital satisfaction and intimacy with child were divided into three groups based on the tertiles: high, medium and low. The results showed that the levels of depression, anxiety, stress and social support were significantly different among the three groups with different marital satisfaction (χ2=125.311, p<0.001; χ2=101.271, p<0.001; F=36.559, p<0.001; F=82.425, p<0.001). There were significant differences in levels of depression, anxiety, stress and social support among parents with different levels of intimacy with their child (χ2=58.186, p<0.001; χ2=40.261, p<0.001; F=25.361, p<0.001; F=34.070, p<0.001). Parents with different parenting styles showed significant differences in depression, anxiety and stress (χ2=37.296, p<0.001; χ2=26.540, p<0.001; F=6.732, p<0.001). Bonferroni post hoc comparisons found that permissive parents had significantly lower levels of depression and anxiety than authoritarian and authoritative parents (p=0.022, p<0.001). Authoritarian parents had significantly higher levels of depression than authoritative parents (p<0.001) (see table 2 for details).

Table 2.

Comparison of scores of PHQ-9, GAD7, PSS-10 and SSRS in various variables

| Variables | PHQ-9 | GAD-7 | PSS-10 | SSRS | |||||||||

| Md (Q1–Q3) | Z/χ2 | P value | Md (Q1–Q3) | Z/χ 2 | P value | M (SD) | F | P value | M (SD) | F | P value | ||

| Gender | Female | 3 (1–6) | −1.601 | 0.109 | 2 (0–4) | −1.569 | 0.117 | 12.58 (5.48) | 0.088 | 0.767 | 44.05 (7.51) | 0.809 | 0.368 |

| Male | 2 (0–6) | 1 (0–4) | 12.35 (5.72) | 43.70 (7.92) | |||||||||

| Domicile | Central China | 4 (1–6.25) | −2.534* | 0.011 | 2 (0–5) | −3.017** | 0.003 | 13.12 (5.49) | 3.297 | 0.070 | 43.82 (7.44) | 0.149 | 0.699 |

| Non-central China | 3 (1–5) | 1 (0–4) | 12.44 (5.53) | 44.01 (7.62) | |||||||||

| Marital status | Married or remarried | 3 (1–6) | −1.771 | 0.077 | 1 (0–4) | −1.945 | 0.052 | 12.48 (5.48) | 1.747 | 0.186 | 44.38 (7.33) | 52.873*** | <0.001 |

| Divorced or widowed | 4 (1–7) | 2 (0–6) | 13.44 (6.35) | 37.38 (8.86) | |||||||||

| Occupation | Workers | 2 (1–6) | 6.690 | 0.350 | 1.5 (0–4.25) | 3.347 | 0.764 | 13.47 (6.06) | 0.714 | 0.639 | 45.34 (8.47) | 2.520* | 0.020 |

| Clerks | 3 (1–5) | 1 (0–4) | 12.51 (5.28) | 43.78 (7.45) | |||||||||

| Civil servants | 3 (0–5) | 1 (0–4) | 12.55 (5.39) | 45.61 (7.24) | |||||||||

| Professional and technical workers | 3 (1–5) | 2 (0–4) | 11.95 (5.70) | 44.51 (7.70) | |||||||||

| Farmers | 4 (1.25–6) | 2 (0–6) | 13.96 (6.08) | 44.21 (6.42) | |||||||||

| Self-employed | 3 (1–6) | 1 (0–4.75) | 12.93 (5.32) | 43.40 (7.56) | |||||||||

| Unemployed | 3 (1–7) | 2 (0–5) | 12.83 (5.93) | 41.79 (7.36) | |||||||||

| Quarantine | Yes | 3 (1–7) | −2.379* | 0.017 | 2 (0–5) | −1.296 | 0.195 | 13.40 (5.57) | 3.341 | 0.068 | 44.06 (7.57) | 0.812 | 0.368 |

| No | 3 (1–5) | 1 (0–4) | 12.41 (5.51) | 43.43 (7.75) | |||||||||

| Parents’ history of mental illness | No | 3 (1–5) | −7.820*** | <0.001 | 1 (0–4) | −9.050*** | <0.001 | 12.21 (5.38) | 48.080*** | <0.001 | 44.30 (7.45) | 24.721*** | <0.001 |

| Yes | 7 (4–9) | 6 (3–8.5) | 16.20 (5.86) | 40.29 (8.25) | |||||||||

| Family economic level | Low | 3.5 (1–6) | −4.012*** | <0.001 | 2 (0–5) | −2.166* | 0.030 | 13.74 (5.58) | 16.746*** | <0.001 | 42.22 (7.91) | 22.761*** | <0.001 |

| Medium or high | 2 (1–5) | 1 (0–4) | 12.08 (5.44) | 44.64 (7.36) | |||||||||

| Child's learning stage | Primary school | 3 (1–6) | 24.428*** | <0.001 | 2 (0–5) | 24.036*** | <0.001 | 13.16 (5.43) | 1.399 | 0.242 | 42.87 (7.73) | 11.981*** | <0.001 |

| Middle school | 3 (1–6) | 2 (0–5) | 12.42 (5.77) | 44.33 (7.34) | |||||||||

| High school | 3 (1–6) | 1 (0–5) | 12.64 (5.11) | 43.06 (7.35) | |||||||||

| College | 2 (0–4) | 0 (0–3) | 11.62 (5.73) | 46.42 (7.60) | |||||||||

| Family conflicts | No | 2 (0–5) | −10.849*** | <0.001 | 1 (0–3) | −11.465*** | <0.001 | 11.81 (5.31) | 81.861*** | <0.001 | 44.73 (7.39) | 45.826*** | <0.001 |

| Yes | 5 (3–8) | 5 (2–7) | 15.36 (5.48) | 41.05 (7.65) | |||||||||

| Marital satisfaction | Low | 4 (2–7) | 125.311*** | <0.001 | 3 (1–6) | 101.271*** | <0.001 | 14.21 (5.31) | 36.559*** | <0.001 | 40.51 (7.53) | 82.425*** | <0.001 |

| Medium | 2 (1–5) | 1 (0–3.25) | 12.24 (5.04) | 45.01 (6.62) | |||||||||

| High | 1 (0–4) | 0 (0–3) | 10.99 (5.71) | 46.77 (7.08) | |||||||||

| Intimacy with child | Low | 3 (1–7) | 58.186*** | <0.001 | 2 (0–5) | 40.261*** | <0.001 | 13.83 (5.23) | 25.361*** | <0.001 | 42.07 (7.52) | 34.070*** | <0.001 |

| Medium | 3 (1–5) | 2 (0–5) | 12.34 (5.36) | 43.82 (7.21) | |||||||||

| High | 1 (0–4) | 0 (0–3) | 11.24 (5.67) | 46.28 (7.38) | |||||||||

| Parenting style | Authoritative | 3 (1–6) | 37.296*** | <0.001 | 2 (0–5) | 26.540*** | <0.001 | 12.83 (5.80) | 6.732*** | <0.001 | 43.82 (7.54) | 1.24 | 0.296 |

| Authoritarian | 7 (3–9) | 3 (1–5) | 15.74 (5.31) | 42.32 (7.45) | |||||||||

| Permissive | 2 (1–5) | 1 (0–4) | 12.12 (5.33) | 44.23 (7.65) | |||||||||

| Uninvolved | 4 (1.75–7) | 2 (0–4.25) | 13.48 (5.54) | 42.95 (6.96) | |||||||||

*P<0.05, **p<0.01,***p<0.001.

GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; M, mean; Md, median; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale-10; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; SSRS, Social Support Rating Scale.

Correlation among anxiety, depression and stress level with various factors

The results of correlation analysis showed that parents’ depression was negatively correlated with age, per capita housing area, social support (r=−0.116, p<0.001; r=0.079, p=0.007; r=−0.366, p<0.001) and parents’ anxiety was negatively correlated with age and social support (r=−0.108, p<0.001; r=−0.305, p<0.001). Anxiety and depression were significantly positively correlated to stress (r=0.571, p<0.001; r=0.521, p<0.001). The results of correlation analyses are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation (Spearman’s correlation, r) of depression, anxiety, stress and various variables

| Age | Education years | Per capita housing area | SSRS | PHQ-9 | GAD-7 | |

| Age | \ | |||||

| Education years | −0.184*** | \ | ||||

| Per capita housing area | 0.162*** | 0.095** | \ | |||

| SSRS | 0.033 | 0.014 | 0.074* | \ | ||

| PHQ-9 | −0.116*** | 0.009 | −0.079** | −0.366*** | \ | |

| GAD-7 | −0.108*** | 0.043 | −0.036 | −0.305*** | 0.720*** | \ |

| PSS-10 | −0.103*** | −0.060* | −0.077** | −0.281*** | 0.521*** | 0.571*** |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale-10; SSRS, Social Support Rating Scale.

Regression analysis of anxiety, depression and various factors

According to the scores of PHQ-9 and GAD-7, the severity of depression and anxiety was divided into four grades (symptomless, mild, moderate and severe). The severity was taken as the dependent variable, and the scores of the PSS-10 and SSRS, as well as the statistically significant factors in the univariate analysis and correlation analysis were used as the independent variables to conduct ordinal regression.

The results showed that stress, marital satisfaction, social support, parents’ history of mental illness, family conflicts and child’s learning stage had significant effects on anxiety. Stress, child in middle or high school were risk factors for anxiety (OR=1.407, 2.045, 2.059, respectively). No family conflicts, high marital satisfaction, good social support and absence of mental illness history were protective factors for anxiety (OR=0.500, 0.987, 0.970, 0.322, respectively) (see table 4 for details).

Table 4.

Ordinal regression with anxiety severity as dependent variable (n=1163)

| Variables | B | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.104 | 0.748 | 1.007 | −0.034 to 0.047 | |

| PSS-10 | 0.341 | 0.024 | 207.26 | <0.001 | 1.407 | 0.295 to 0.388 | |

| Marital satisfaction | −0.013 | 0.004 | 9.260 | 0.002 | 0.987 | −0.021 to −0.005 | |

| Intimacy with child | 0.006 | 0.006 | 1.138 | 0.286 | 1.006 | −0.005 to 0.017 | |

| SSRS | −0.031 | 0.012 | 6.378 | 0.012 | 0.970 | −0.055 to −0.007 | |

| Parents’ history of mental illness | No | −1.133 | 0.251 | 20.404 | <0.001 | 0.322 | −1.624 to −0.641 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Family conflicts | No | −0.694 | 0.191 | 13.139 | <0.001 | 0.500 | −1.069 to −0.319 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Family economic level | Low | −0.068 | 0.185 | 0.134 | 0.714 | 0.934 | −0.430 to 0.295 |

| Medium or high | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Domicile | Central China | 0.107 | 0.256 | 0.176 | 0.675 | 1.113 | −0.395 to 0.610 |

| Non-central China | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Child’s learning stage | Primary school | −0.432 | 0.337 | 1.642 | 0.200 | 1.540 | −1.092 to 0.229 |

| Middle school | −0.716 | 0.303 | 5.573 | 0.018 | 2.045 | −1.310 to −0.121 | |

| High school | −0.722 | 0.311 | 5.396 | 0.020 | 2.059 | −1.332 to −0.113 | |

| College | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Parenting style | Authoritative | −0.635 | 0.468 | 1.836 | 0.175 | 1.886 | −1.553 to 0.283 |

| Authoritarian | −0.282 | 0.549 | 0.264 | 0.608 | 1.326 | −1.358 to 0.794 | |

| Permissive | −0.005 | 0.458 | <0.001 | 0.992 | 1.005 | −0.902 to 0.893 | |

| Uninvolved | 0 | 1 | |||||

B, beta-value; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale-10; SE, Standard Error; SSRS, Social Support Rating Scale.

Stress, marital satisfaction, social support, parents’ history of mental illness and family conflicts had significant effects on depression. Stress was a risk factor for depression (OR=1.226). No family conflicts, high marital satisfaction, good social support and the absence of mental illness history in parents were protective factors for depression (OR=0.565, 0.990, 0.959, 0.461, respectively) (see table 5 for details).

Table 5.

Ordinal regression with depression severity as dependent variable (n=1163)

| Variables | B | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age | −0.016 | 0.018 | 0.876 | 0.349 | 0.984 | −0.051 to 0.018 | |

| PSS-10 | 0.203 | 0.016 | 152.328 | <0.001 | 1.226 | 0.171 to 0.236 | |

| Marital satisfaction | −0.010 | 0.004 | 7.992 | 0.005 | 0.990 | −0.017 to −0.003 | |

| Intimacy with child | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.069 | 0.792 | 1.001 | −0.008 to 0.011 | |

| SSRS | −0.042 | 0.010 | 16.106 | <0.001 | 0.959 | −0.063 to −0.021 | |

| Per capita housing area | −0.002 | 0.005 | 0.095 | 0.758 | 0.998 | −0.012 to 0.008 | |

| Parents’ history of mental illness | No | −0.775 | 0.231 | 11.236 | 0.001 | 0.461 | −1.228 to −0.322 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Quarantine | No | 0.013 | 0.208 | 0.004 | 0.951 | 1.013 | −0.395 to 0.421 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Family conflicts | No | −0.570 | 0.169 | 11.403 | 0.001 | 0.565 | −0.901 to −0.239 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Family economic level | Low | 0.050 | 0.160 | 0.100 | 0.752 | 1.052 | −0.262 to 0.363 |

| Medium or high | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Domicile | Central China | 0.286 | 0.221 | 1.670 | 0.196 | 1.331 | −0.147 to 0.719 |

| Non-central China | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Child’s learning stage | Primary school | −0.074 | 0.270 | 0.076 | 0.783 | 1.077 | −0.603 to 0.454 |

| Middle school | −0.202 | 0.242 | 0.700 | 0.403 | 1.224 | −0.676 to 0.272 | |

| High school | −0.074 | 0.248 | 0.088 | 0.767 | 1.076 | −0.560 to 0.413 | |

| College | 0 | 1 | |||||

| Parenting style | Authoritative | 0.225 | 0.376 | 0.359 | 0.549 | 0.798 | −0.511 to 0.962 |

| Authoritarian | −0.225 | 0.446 | 0.255 | 0.614 | 1.252 | −1.099 to 0.649 | |

| Permissive | 0.378 | 0.362 | 1.089 | 0.297 | 0.685 | −0.332 to 1.088 | |

| Uninvolved | 0 | 1 | |||||

B, beta-value; GAD-7, Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PSS-10, Perceived Stress Scale-10; SE, Standard Error; SSRS, Social Support Rating Scale.

Discussion

Main findings

In the present study, the detection rates of anxiety and depression in students’ parents were 6.1% and 4.0%, which were lower than the previous studies.17–19 This may be because of the difference in sample composition. Besides, this survey was conducted in the late period of the COVID-19 pandemic, and parents’ anxiety and depression may have been relieved. Therefore, it can be considered that parental depression and anxiety levels were relatively low in the late period of the outbreak.

This study explored the relationships between different factors and parental mental health. The study found no significant gender differences in parental anxiety, depression and stress, while past research has shown that women are more susceptible to stress than men and tend to show greater emotional responses.20 The reason may be that the results of this study were biassed due to the small sample size of men. The previous study has found that psychological distress was highest in people of central China during the COVID-19 pandemic, significantly higher than in other regions.2 Therefore, this study also compared the mental health of parents in central China and non-central China. The results showed that parents in central China had significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression than parents in non-central China. However, the stress of parents in central China was not significantly different from that in non-central China, which may be because the investigation time of this study was relatively late, the peak of the stress response has passed and the difference of stress response was transformed into the differences of depression and anxiety. Parents who were quarantined or whose family members were quarantined for 2 weeks have higher levels of depression than those who had no family members being quarantined, the recent study has found that although isolation reduced the spread of the virus, it led to negative emotional experiences such as depression and anxiety.21 Mental illness of parents can significantly affect the depression, anxiety and stress of parents. On the one hand, the basis of mental illness makes parents more sensitive to the environment; on the other hand, during the pandemic, parents cannot go to the doctor normally, which further affects the mood of parents.

This study focused on the influence of family related factors on the psychological status of parents and found that parents with family conflicts had significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety and stress than parents with a harmonious family. Parental marital satisfaction and intimacy with their children can significantly affect parental mental health. Parents with high marital satisfaction and intimacy with their children had lower levels of depression, anxiety and stress. These two factors reflect a stable and harmonious family environment. The analysis of social support also found that parents with higher marital satisfaction and intimacy with their children had better social support. This result is consistent with previous research showing that social support is influenced by the family environment, and family environment factors can influence mental health by influencing social support.22

The depression and anxiety of college students’ parents were significantly lower than that of the parents of students in other learning stages. This may be related to the social support parents received from children. The social support felt by parents of college students was significantly higher than that of other parents. College students may be an important source of social support for their parents.

The depression, anxiety and stress of parents with low family economic level were significantly higher than those with high economic level, which is consistent with previous studies, family economic condition is an important factor affecting individual’s mental health.23 In the case of the pandemic, people’s incomes are affected to varying degrees. Families with a lower economic level will be more affected, which may lead to more stress responses, anxiety and depression among these parents.

The mental health of parents with different parenting styles was also significantly different, and the anxiety, depression and stress of parents with permissive parenting styles were significantly lower than those with authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles. Authoritative and authoritarian parents tend to be more demanding on their children than permissive parents. A previous study has shown that parenting styles are associated with parent-child conflicts and affect children’s behaviours.24 During the pandemic, children have to study at home, and the parents spend more time together with the children, the children’s performances may not meet the requirements of these parents, which may lead to conflicts and affect the parents’ emotions.

Correlation analysis found that parents’ depression, anxiety and stress were negatively correlated with age; years of education was negatively correlated with stress level, and per capita housing area was significantly correlated with depression and stress level. Further regression results showed that parents’ history of mental illness, marital satisfaction, stress, social support, family conflicts and child’s learning stage had significant effects on parental anxiety. Stress, marital satisfaction, social support, parents’ history of mental illness and family conflicts had significant effects on depression. This result indicates that stress response and social support jointly affect the depression and anxiety of individuals during the pandemic, which is consistent with the results of previous studies.9 Among family related factors, high marital satisfaction and harmonious family environment are protective factors for anxiety and depression, and the results are consistent with previous researches. Chen and Tian25 found that marital satisfaction is an important factor affecting the mental health of rural women. Family relationships can affect mental health, and living in an unharmonious family can lead to anxiety and depression.26 Parents with children in middle or high school is a risk factor for anxiety, this may be because middle and high school students have heavier study tasks, and the pandemic prevents students from returning to school, so their parents may feel more anxious.

Limitations

First of all, in the sample selection, the researchers recruited subjects from online platforms, and the parents of the students who voluntarily filled in the survey may generally have good mental health status, so the detection rates of depression and anxiety were relatively low, and the research results are biassed to some extent. Second, the survey was conducted at a relatively late stage of the pandemic, and the parents’ depression, anxiety and stress response were in remission. Therefore, the survey only reflects the influence of the pandemic and family relationship on parental mental health to a certain extent.

Implications

This study explored the mental health status of the students’ parents during home quarantine and investigated the influence of various factors on the psychological status of the parents. The results showed that parents’ mental health should be paid attention to during the COVID-19 epidemic, and good marriage relationship, good social support, family harmony and parents without a history of mental illness may be protective factors of parental mental health, while stress and parents with children in middle or high school are risk factors for parental mental health. This study provides an important basis for further targeted parental psychological intervention.

Biography

Mengting Wu graduated from Nanjing Normal University, China, in 2019. She has started a master's program in clinical psychology in Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, since 2019. Her main research interest includes eating disorders.

Footnotes

Contributors: MW contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing. WX and JC designed the study and contributed to all aspects of implementation. YY helped in subject recruitment and study implementation. LZ, LG and JF helped in subject recruitment and literature search. All authors contributed to and have checked the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Shanghai Clinical Research Center for Mental Health (SCRC-MH) (19MC1911100); National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771461); Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2019ZB0201); Xuhui District Health and Family Planning Commission Important Disease Joint Research Project (XHLHGG201808).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Shanghai Mental Health Center affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University (number: 2020-32).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Tong HJ. [Model of SARS stress and it' s character]. Xin Li Xue Bao 2004;36:103–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr 2020;33:e100213. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang YN, Luo YJ. [Specialty of mood disorders and treatment during emergent events of public health]. Xin Li Ke Xue Jin Zhan 2003;11:387–92. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eli B, Cheng J, Liang YM, et al. [Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression prevalence among enterprise employees after an accident disaster]. Zhongguo Gong Gong Wei Sheng Za Zhi 2018;34:1355–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5. SP Y. [Study on chronic post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety symptoms of junior high school students after Wenchuan earthquake]. Xian Dai Yu Fang Yi Xue 2014;41:2036–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Han HQ, Chen J, Xie B. [Psychological problems in recovered patients with new coronavirus pneumonia and intervention strategies]. Shanghai Yi Xue 2020:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang YF. [An Introduction of the Theory and Researches of Social Support]. Xin Li Ke Xue 2004;27:1175–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tong HJ. [A confirmative research on social support and SARS stress]. Xin Li Ke Xue 2004;27:380–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guo L, PR X, Yao F, et al. [The effect of acute stress disorder on negative emotions in Chinese public under major epidemic conditions - the moderating effect of social support]. Xi Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Zi Ran Ke Xue Ban 2020;42:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann 2002;32:509–15. 10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Y-L, Liang W, Chen Z-M, et al. Validity and reliability of patient health Questionnaire-9 and patient health Questionnaire-2 to screen for depression among college students in China. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2013;5:268–75. 10.1111/appy.12103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qu S, Sheng L. [Diagnostic test of screening generalized anxiety disorders in general hospital psychological department with GAD-7]. Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi 2015;29:939–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen S, Kamarck T. Mermelstein R. a global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1984;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang Z, Wang Y, ZG W, et al. [Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Perceived Stress Scale]. Shanghai Jiao Tong Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2015;35:1448–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu JW, FY L, Lian YL. [Investigation of reliability and validity of the social support scale]. Xinjiang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2008;31:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang HY, Yang FC, Chen HY, et al. [Depression Status of Community Residents in Karamay District of Xinjiang Uygar Autonomous Region and Its Influencing Factors]. Zhongguo Quan Ke Yi Xue 2012;15:1875–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu MF, Zhang MH, Zhang WQ, et al. [Depression Status of Rural Community Residents in Chaoyang District of Beijing]. Zhongguo Quan Ke Yi Xue 2013;16:3009–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang LP, Huang RY, Wang ZW, et al. [Relationship among depression, anxiety and social support in elderly patients from community outpatient clinic]. Zhong Hua Xing Wei Yi Xue Yu Nao Ke Xue Za Zhi 2019;28:580–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang LW, Yang LH, Xb C, et al. [The investigation of psychological status of medical staff during epidemic outbreak stage of SARS in Wuhan]. Zhongguo Xing Wei Yi Xue Ke Xue 2003;12:76–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yuan J, YH D, Xu W, et al. [Study on the anxiety and depression levels and influencing factors in patients with suspected corona virus disease 2019 in isolation]. Chongqing Yi Xue 2020:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22. WF W, YB L. [The Influence of Family Environment and Personality on College Student’ s Social Support]. Zhongguo Lin Chuang Xin Li Xue Za Zhi 2006;14:190–1. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liang ZH, Hao YT, Wang YF, et al. [A comparative study on the mental health of elderly population and its relation to personal income]. Zhongguo Lao Nian Xue Za Zhi 2010;30:1414–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24. CH S, Conflict MB. Support and coping as mediators of the relation between degrading parenting and adolescent adjustment. J Youth Adolesc 2006;35:599–611. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen HY, Tian XJ. [Research on the relationship between marital quality and mental Health of new countryside women]. Xian Dai Yu Fang Yi Xue 2010;37:4269–70. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ying Z. [Influencing factors of mental health of the elderly and their influence on children's social attributes]. Zhongguo Lao Nian Xue Za Zhi 2013;33:5678–80. [Google Scholar]