Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate sella turcica (ST) bridging, associated anomalies, and morphology, in subjects with four different types of clefts, and compare them with non-cleft (NC) subjects.

Materials and Methods

A total of 123 (31 NC and 92 cleft) Saudi subjects who had their lateral cephalogram (Late. Ceph.), orthopantomogram (OPG), and clinical details for ordinary diagnosis were included in the study. Among 92 cleft subjects, 29 had bilateral cleft lip and palate (BCLP), 41 had unilateral cleft lip and palate (UCLP), nine had unilateral cleft lip and alveolus (UCLA), and 13 with unilateral cleft lip (UCL). ST bridging and seven parameters related to ST morphology and skeletal malocclusion were analyzed using Late. Ceph. Associated dental anomalies in ST bridging subjects were investigated using OPG. The images were investigated using artificial intelligence driven Webceph software. Multiple statistical tests were applied to see the differences between gender and among cleft vs NC subjects.

Results

ST bridging was found to be higher in cleft subjects (22.82%). Most of the cleft subjects had severe skeletal Class III malocclusion associated with multiple types of dental anomalies (impacted canines, congenital missing, and presence of supernumerary teeth). No significant gender disparities in all seven parameters of ST morphology were found between NC and cleft groups. However, there were significant differences when compared among four different types of cleft individuals vs NC subjects.

Conclusion

ST bridging is more prevalent in cleft subjects along with Class III malocclusion and associated dental anomalies. ST morphometry differs significantly between cleft vs NC subjects. BCLP exhibits smaller values of all seven parameters as compared to all other groups.

Keywords: sella turcica, sella turcica bridging, morphometry, bilateral cleft lip and palate, unilateral cleft lip and palate

Introduction

Lateral cephalogram (Late. Ceph.) uses a number of landmarks as reference points for analysis/study of craniofacial structures. Sella turcica (ST) serves as one such important landmark in the cranium on Late. Ceph. The sella point or the center of the ST is a point in the cranial base which is situated at the midpoint of ST that accommodates the pituitary gland (Celik-Karatas et al., 2015). It plays an important role in cephalometric analysis and helps us identify pathologies related to pituitary gland and hence becomes an exceptional source of information, specifically those syndromes that affect craniofacial region. A thorough knowledge of its radiological anatomy and variations may help us evaluate the growth and recognize any deviation in a variety of anomalies or pathological situations, and the possible outcome of the orthodontic treatment in such situations.

Congenital anomalies, though identified at birth often, get initiated during pregnancy due to chromosomal abnormalities. A gamut of congenital anomalies occurs in the craniofacial region, cleft lip and palate (CLP) being the most common anomaly in the head and neck region, only second to congenital heart disease in the whole body. Hence, cleft deformities have been included in their Global Burden of Disease initiative, by World Health Organization (WHO). CLP is quite variable in its presentation and affects about 1.17/1000 birth overall 1.30 of every 1000 live births in Saudi (Sabbagh et al., 2015) and Asian populations (Cooper et al., 2006). CLP has a multifactorial etiology with genetics and environmental factors to be the major contributing factors (Mars and Houston, 1990). The clefts have been classified depending upon the extent of involvement and their location as cleft palate, cleft lip, unilateral cleft lip (UCL), unilateral cleft lip and alveolus (UCLA), unilateral cleft lip and palate (UCLP), bilateral cleft lip and palate (BCLP), etc. The affected children may have retarded maxillary growth (Alam et al., 2013), malposed teeth, crowding and rotation of teeth, and a high incidence of class III malocclusion (Haque and Alam, 2015).

Most of the previous studies relating to craniofacial anomalies have used 2D imaging, such as Late. Ceph. which was cost-effective with low radiation exposure and the study of various landmarks were done efficiently by linear and angular measurements (Alkofide, 2008). The morphology of ST can be efficiently measured with Late. Ceph. With the advancement in radiographic techniques and imaging, there is a shift toward 3D imaging techniques, particularly 3D imaging using CT scan (Hasan et al., 2016a,b, 2019; Islam et al., 2017) and CBCT (Yasa et al., 2017) as they give a better and accurate extent of the lesions in a 3D view and hence play a key role in the diagnosis and treatment of craniofacial malformations.

Extensive search of literature relating to the measurement of ST revealed that there was only one study on clefts in Saudi population with little or no focus on its relation to ST (Alkofide, 2008). Very few studies have evaluated the postnatal development and structure of ST and its relation to clefts (Alkofide, 2008; Yasa et al., 2017) which measured only three parameters to establish the morphology of ST. Due to limited research in this area and alarming number of individuals with clefts without the syndrome in Saudi Arabia with this genotype, the current investigation was undertaken to calculate the seven parameters of morphology of the ST, and to compare the findings with non-cleft (NC) healthy subjects with the following aims:

-

1.

Investigation of ST bridging, type of skeletal malocclusion, and different dental anomalies.

-

2.

Gender disparities of seven parameters of morphology of the ST among cleft and NC subjects.

-

3.

Multiple comparisons of seven parameters of morphology of the ST among four different types of cleft and NC subjects.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective study, clinical and radiographic details of 31 NC subjects and 92 cleft subjects were used. All the records were collected from Saudi board Dental residents. The research protocol was prepared by one calibrated specialist orthodontist and the data were stored. The protocol was submitted for ethical board review. After approval, data investigations and analysis were completed. The details of ethical approval number are shown in Table 1. Out of 92 cleft subjects, 29 had BCLP, 41 had UCLP, nine had UCLA, and 13 had UCL as per cleft classification details from the clinical records. The details of age and gender distribution, demographic details, and inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic details and methods.

| Population | Saudi subjects | ||||||

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Non syndromic cleft subjects with good quality x-ray images. No history of craniofacial surgical treatment besides lip and palate surgery. No orthodontic treatment has been done. No anatomical variation in the ST and sphenoidal regions. Matched with healthy control without any craniofacial deformity. Subjects using hormonal medications or corticosteroids were excluded from the study. | ||||||

| Sampling | Convenient sampling following inclusion and exclusion criteria. | ||||||

| Type of cleft | Non-cleft | BCLP | UCLP | UCLA | UCL | ||

| Subjects distribution | Male | 14 | 19 | 26 | 3 | 7 | |

| Female | 17 | 10 | 15 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Total (N = 123) | 31 | 29 | 41 | 9 | 13 | ||

| Age | 13.29 ± 3.52 | 14.07 ± 4.73 | 14.32 ± 4.46 | 12.78 ± 4.09 | 13.31 ± 4.46 | ||

| Data used | Digital lateral cephalogram, orthopantomogram, and clinical record details. | ||||||

| Ethical clearance | Protocol has been presented to the ethical board of Alrass Dental Research Center, Qassim University. Ethical clearance has been obtained with the Code #: DRC/009FA/20. | ||||||

| Method | Artificial intelligence driven technique using Webceph software (Korea) | ||||||

| Landmarks used and the details | TS | Tuberculum sella | The most anterior point of the contour of the sella turcica | ||||

| DS | Dorsum sellae | The posterior wall of the sella turcica | |||||

| SF | Sella floor | The deepest point on the floor of pituitary fossa | |||||

| Pclin | Posterior clenoid | The most anterior point of the PClin process | |||||

| SA | Sella anterior | The most anterior point of the sella | |||||

| SP | Sella posterior | The most posterior point of the sella | |||||

| SM | Sella median | A point midway between PClin and TS | |||||

| Measurements (seven parameters) | Significance/importance | ||||||

| a | Sella length | TS-Pclin | Changes in the size of sella turcica are often identified with the pathology of pituitary gland and may have an undetected hidden disease; hence, sella length is one of the parameters to determine the sella size. | ||||

| b | Sella width | SA-SP | Utilized clinically for pubertal growth phase determination, would be increased by advanced age, it has strong correlation with age. | ||||

| c | Sella diameter | TS-DS | Growth of an individual can be assessed based on the diameter of the sella turcica at different age periods. | ||||

| d | Sella height anterior | TS-SF | As the anterior part of the sella turcica is believed to develop mainly from neural crest cell, so we need to measure the sella height anterior. So that, we can assume or determine any structural deviation in the anterior wall which are believed to be associated with the specific deviation in the facial structure. | ||||

| e | Sella height posterior | PClin-SF | The posterior part of the sella turcica develops from the para-axial-mesoderm, which develops approximately 7 weeks of gestation. If any disturbance occurs in this area it remains throughout the life, as the time of formation of sella closely associated with the development of maxilla. So that, it may be assumed that any aberration leading to cleft may be associated with some fault at the level of sella turcica. | ||||

| f | Sella height median | SM-SF | Utilized clinically for pubertal growth phase determination, would be increased with age. | ||||

| g | Sella area | TS-SA-SF-SP-Pclin | During embryological development of the sella area is the key point for the migration of the neural crest cells to the fronto nasal and maxillary developmental fields. Pituitary fossa increased in size with age and found a positive correlation of the area of the sella to age. | ||||

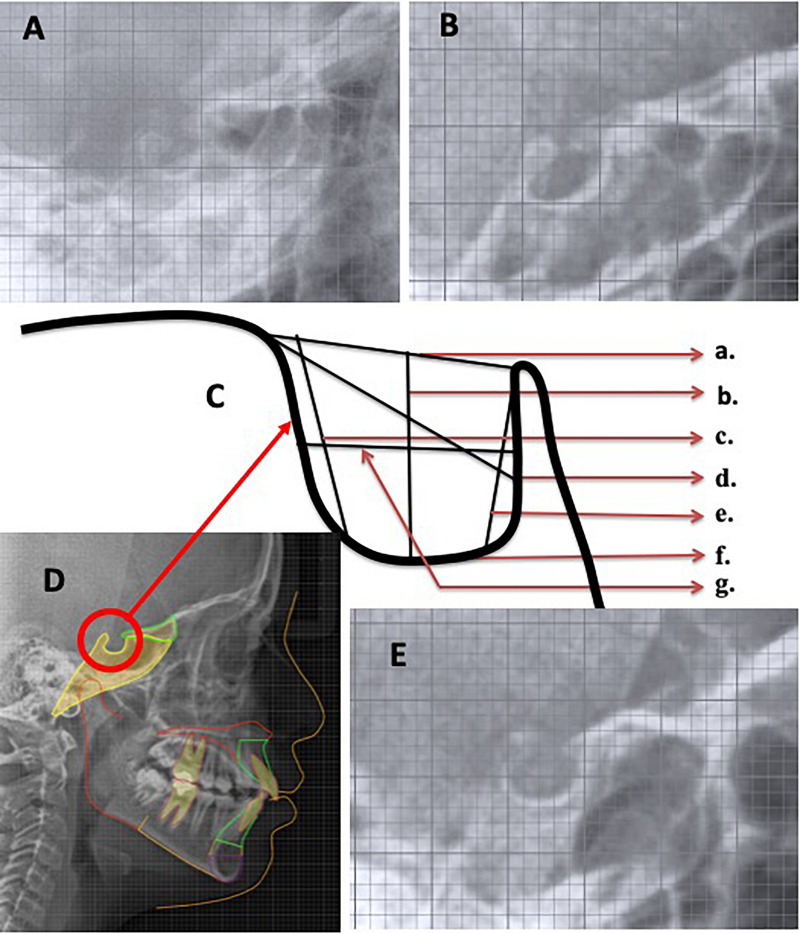

Lateral cephalogram X-rays were used to investigate of ST bridging by two observers and the data were recorded after agreement by both the observers and analyzed. In a similar manner, each orthopantomogram (OPG) was investigated and dental anomalies are listed after agreement by both the observers in cases with ST bridging. Late. Ceph. X-ray was also used for skeletal class of malocclusion assessment (based on ANB and Wits measurement) only in cases with ST bridging and seven parameters of ST morphology in all subjects (Hasan et al., 2016a,b, 2019; Islam et al., 2017) were measured by one examiner using artificial intelligence driven Webceph software (Korea). The details of the seven parameters measurements are presented in Table 1 (Hasan et al., 2016a,b, 2019; Islam et al., 2017) and shown in Figure 1 (Hasan et al., 2016a,b, 2019; Islam et al., 2017).

FIGURE 1.

Lateral cephalogram view of sella turcica in (A) BCLP, (B) UCLP, (C) sella turcica parameters: (a) TS-Pclin; (b) SA-SP; (c) TS-DS; (d) TS-SF; (e) PClin-SF; (f) SM-SF; and (g) sella area, (D) Control, and (E) UCLA subjects.

Statistical Analyses

After a 2-week interval, 20 randomly selected X-rays were used for re-measurement in a similar fashion. For ST bridging and dental anomalies results were tested using Kappa test for intra and inter-examiner reliability. Error testing in the investigation of ST morphology based on seven parameters measurements were tested by intra-class correlation co-efficient (ICC) test. Total investigated data were analyzed using version 26.0 SPSS software (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Normality of the measured seven parameters of ST morphology data was assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each parameter and presented in a tabulated format. Independent t-test was used for gender disparities and ANOVA test used for multiple comparison among NC and all four types of cleft groups.

Results

Using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, measured seven parameters of ST morphology data were found normally distributed. Error test results of the ST bridging and dental anomalies investigation showed excellent intra and inter-examiner reliability. ICC results for all seven parameters of ST morphology ranged from 0.86 to 0.94.

Prevalence of ST bridging, type of malocclusion involved, and associated dental anomalies are listed in Table 2. Overall, 6.45 and 22.82% ST bridging was found in NC and cleft individuals, respectively. Among four types of clefts, ST bridging found, UCL > UCLP > BCLP > UCLA. Highest % in UCL (30.77%). Skeletal Class III malocclusion was found to be more prevalent in ST bridging individuals. Among dental anomalies, impacted canine, congenital missing, and supernumerary teeth were found to be common.

TABLE 2.

Sella turcica bridging, type of malocclusion and associated anomalies.

| Gender | Sella bridging | Subject | Skeletal malocclusion | Dental anomalies | Prevalence |

| F | Complete | Non-cleft | Class I | IC | Non-cleft = 6.45% |

| M | Partial | Non-cleft | Class II | IC | |

| F | Partial | Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate | Class III | CM + IC | BCLP = 20.69% |

| M | Partial | Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate | Class III | CM | |

| M | Partial | Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate | Class III | None | |

| M | Partial | Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate | Class III | CM | |

| M | Partial | Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate | Class III | CM + IC | |

| M | Partial | Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate | Class III | None | |

| M | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Lt Side | Class III | CM | UCLP = 24.39% |

| F | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Lt Side | Class III | IC | |

| M | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Lt Side | Class III | CM | |

| F | Complete | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Lt Side | Class III | CM + IC | |

| F | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Lt Side | Class III | CM + IC | |

| M | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Lt Side | Class III | IC | |

| F | Complete | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Lt Side | Class III | CM + IC + Dilaceration | |

| M | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Rt Side | Class I | CM | |

| M | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Rt Side | Class III | CM + IC | |

| M | Complete | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Palate Rt Side | Class I | CM | |

| F | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip and Alveolus Rt Side | Class III | CM | UCLA = 11.11% |

| F | Complete | Unilateral Cleft Lip Lt Side | Class III | CM | UCL = 30.77% |

| M | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip Rt Side | Class III | SN | |

| M | Partial | Unilateral Cleft Lip Rt Side | Class II | CM + IC | |

| F | Complete | Unilateral Cleft Lip Rt Side | Class III | CM |

Non-cleft = M, male; F, female; IC, impacted canine; CM, congenital missing; SN, supernumerary tooth.

Table 3 shows the details of descriptive and comparative gender disparities results among NC and different types of clefts (NC, BCLP, UCLP, UCLA, and UCL). Overall ST morphometry has been presented which shows no significant gender disparities.

TABLE 3.

Gender disparities of all sella turcica morphomometric parameters among all five groups.

| Group | Variables | Gender | Mean | SD | 95% CI |

p | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Control | A | Male | 11.164 | 1.690 | −0.685 | 1.369 | 0.501 |

| Female | 10.822 | 1.090 | |||||

| B | Male | 9.669 | 1.466 | −1.105 | 1.123 | 0.987 | |

| Female | 9.659 | 1.544 | |||||

| C | Male | 10.925 | 3.296 | −1.489 | 2.966 | 0.503 | |

| Female | 10.187 | 2.771 | |||||

| D | Male | 8.210 | 1.461 | −0.649 | 1.708 | 0.366 | |

| Female | 7.681 | 1.698 | |||||

| E | Male | 7.779 | 0.911 | −1.049 | 1.329 | 0.812 | |

| Female | 7.639 | 2.007 | |||||

| F | Male | 8.746 | 1.131 | −0.531 | 1.355 | 0.379 | |

| Female | 8.335 | 1.385 | |||||

| G | Male | 77.133 | 22.446 | −9.325 | 23.683 | 0.381 | |

| Female | 69.954 | 22.288 | |||||

| BCLP | A | Male | 8.075 | 0.989 | −0.390 | 1.495 | 0.239 |

| Female | 7.522 | 1.480 | |||||

| B | Male | 7.422 | 1.289 | −0.520 | 1.639 | 0.297 | |

| Female | 6.862 | 1.455 | |||||

| C | Male | 7.663 | 2.258 | −1.330 | 2.366 | 0.570 | |

| Female | 7.145 | 2.398 | |||||

| D | Male | 6.254 | 1.487 | −0.897 | 1.452 | 0.632 | |

| Female | 5.977 | 1.420 | |||||

| E | Male | 6.229 | 1.142 | −0.876 | 1.083 | 0.829 | |

| Female | 6.125 | 1.368 | |||||

| F | Male | 7.210 | 1.308 | −0.928 | 1.365 | 0.699 | |

| Female | 6.991 | 1.650 | |||||

| G | Male | 49.767 | 17.188 | −9.614 | 18.425 | 0.525 | |

| Female | 45.362 | 18.076 | |||||

| UCLP | A | Male | 8.223 | 1.266 | −0.381 | 1.308 | 0.273 |

| Female | 7.759 | 1.324 | |||||

| B | Male | 7.774 | 1.492 | −1.081 | 1.018 | 0.951 | |

| Female | 7.806 | 1.778 | |||||

| C | Male | 9.392 | 2.418 | −1.659 | 1.480 | 0.908 | |

| Female | 9.481 | 2.348 | |||||

| D | Male | 6.903 | 1.227 | −1.034 | 0.513 | 0.499 | |

| Female | 7.164 | 1.089 | |||||

| E | Male | 6.895 | 1.054 | −0.798 | 0.549 | 0.710 | |

| Female | 7.019 | 0.977 | |||||

| F | Male | 7.278 | 1.158 | −0.872 | 0.582 | 0.689 | |

| Female | 7.423 | 1.013 | |||||

| G | Male | 57.560 | 12.685 | −6.058 | 10.327 | 0.601 | |

| Female | 55.425 | 12.139 | |||||

| UCL | A | Male | 8.873 | 1.495 | −0.940 | 2.356 | 0.365 |

| Female | 8.165 | 1.141 | |||||

| B | Male | 8.034 | 1.636 | −1.968 | 2.016 | 0.979 | |

| Female | 8.010 | 1.616 | |||||

| C | Male | 9.739 | 2.744 | −3.412 | 2.480 | 0.734 | |

| Female | 10.205 | 1.923 | |||||

| D | Male | 7.199 | 1.377 | −2.404 | 0.968 | 0.369 | |

| Female | 7.917 | 1.378 | |||||

| E | Male | 7.543 | 0.845 | −1.474 | 1.400 | 0.956 | |

| Female | 7.580 | 1.474 | |||||

| F | Male | 7.711 | 1.692 | −2.626 | 1.652 | 0.626 | |

| Female | 8.198 | 1.810 | |||||

| G | Male | 62.428 | 21.557 | −29.800 | 19.872 | 0.669 | |

| Female | 67.392 | 18.638 | |||||

| UCLA | A | Male | 8.303 | 1.414 | −2.153 | 1.033 | 0.433 |

| Female | 8.863 | 0.686 | |||||

| B | Male | 8.120 | 1.026 | −3.044 | 2.150 | 0.696 | |

| Female | 8.567 | 1.719 | |||||

| C | Male | 10.167 | 0.257 | −3.081 | 4.514 | 0.669 | |

| Female | 9.450 | 2.683 | |||||

| D | Male | 6.823 | 0.770 | −2.662 | 2.129 | 0.800 | |

| Female | 7.090 | 1.624 | |||||

| E | Male | 6.923 | 1.822 | −3.178 | 3.048 | 0.962 | |

| Female | 6.988 | 1.878 | |||||

| F | Male | 7.040 | 1.574 | −3.876 | 2.599 | 0.655 | |

| Female | 7.678 | 2.064 | |||||

| G | Male | 54.233 | 10.970 | −39.066 | 31.380 | 0.804 | |

| Female | 58.076 | 23.940 | |||||

* p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Table 4 shows the description total details among all five groups (NC, BCLP, UCLP, UCLA, and UCL) subjects. Multiple comparison results are presented in Table 5. Significantly larger TS-Pclin has been found in NC group in comparison to all four-cleft group (p < 0.001). However, there are no significant differences within the cleft group found. Smallest value found in BCLP group was 7.884 mm. Sa-SP value shows significant disparities between NC vs BCLP (p < 0.001), NC vs UCLP (p < 0.001), and NC vs UCL (p = 0.012) groups. When TS-DS values were compared, NC vs BCLP (p < 0.001), BCLP vs UCLP (p = 0.018) and UCL (p = 0.037) showed significant disparities. There were significant disparities between NC vs BCLP (p < 0.001) and BCLP vs UCL (p = 0.019) in PClin-SF parameter. And, when compared the parameters of SM-SF and TS-SA-SF-SP-PClin, NC vs BCLP and NC vs UCLP shows significant disparities. In BCLP group, values of all seven parameters of ST morphometry showed smallest values in comparison with all four groups.

TABLE 4.

Descriptive results of all sella turcica morphomometric parameters among all five groups.

| TS-PClin |

SA-SP |

TS-DS |

TS-SF |

PClin-SF |

SM-SF |

TS-SA-SF-SP-PClin |

||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Control | 10.976 | 1.379 | 9.664 | 1.484 | 10.520 | 2.991 | 7.920 | 1.592 | 7.702 | 1.585 | 8.521 | 1.273 | 73.196 | 22.281 |

| BCLP | 7.884 | 1.185 | 7.229 | 1.350 | 7.484 | 2.278 | 6.159 | 1.445 | 6.193 | 1.201 | 7.134 | 1.409 | 48.248 | 17.306 |

| UCLP | 8.053 | 1.291 | 7.786 | 1.580 | 9.424 | 2.363 | 6.999 | 1.172 | 6.940 | 1.016 | 7.331 | 1.096 | 56.779 | 12.378 |

| UCL | 8.546 | 1.340 | 8.023 | 1.557 | 9.954 | 2.316 | 7.530 | 1.370 | 7.560 | 1.124 | 7.936 | 1.691 | 64.720 | 19.589 |

| UCLA | 8.677 | 0.934 | 8.418 | 1.470 | 9.689 | 2.155 | 7.001 | 1.347 | 6.967 | 1.742 | 7.466 | 1.839 | 56.795 | 19.799 |

TABLE 5.

Multiple comparison of all sella turcica morphomometric parameters among all five groups.

| Variables | Multiple comparison | MD | SE | 95% CI |

p-Value | |||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | |||||||

| TS-PClin | Control | vs | BCLP | 3.09199* | 0.329 | 2.150 | 4.034 | 0.000 |

| UCLP | 2.92271* | 0.303 | 2.055 | 3.790 | 0.000 | |||

| UCL | 2.42998* | 0.421 | 1.226 | 3.634 | 0.000 | |||

| UCLA | 2.29946* | 0.482 | 0.919 | 3.680 | 0.000 | |||

| BCLP | vs | UCLP | −0.16928 | 0.309 | −1.054 | 0.715 | 1.000 | |

| UCL | −0.66202 | 0.425 | −1.879 | 0.555 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLA | −0.79253 | 0.486 | −2.183 | 0.598 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLP | vs | UCL | −0.49274 | 0.406 | −1.653 | 0.667 | 1.000 | |

| UCLA | −0.62325 | 0.469 | −1.965 | 0.718 | 1.000 | |||

| UCL | vs | UCLA | −0.13051 | 0.552 | −1.711 | 1.450 | 1.000 | |

| SA-SP | Control | vs | BCLP | 2.43493* | 0.386 | 1.331 | 3.539 | 0.000 |

| UCLP | 1.87769* | 0.356 | 0.860 | 2.895 | 0.000 | |||

| UCL | 1.64047* | 0.494 | 0.228 | 3.053 | 0.012 | |||

| UCLA | 1.24577 | 0.566 | −0.373 | 2.864 | 0.296 | |||

| BCLP | vs | UCLP | −0.55723 | 0.363 | −1.594 | 0.480 | 1.000 | |

| UCL | −0.79446 | 0.499 | −2.221 | 0.632 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLA | −1.18916 | 0.570 | −2.820 | 0.442 | 0.391 | |||

| UCLP | vs | UCL | −0.23722 | 0.476 | −1.598 | 1.123 | 1.000 | |

| UCLA | −0.63192 | 0.550 | −2.205 | 0.941 | 1.000 | |||

| UCL | vs | UCLA | −0.3947 | 0.648 | −2.248 | 1.459 | 1.000 | |

| TS-DS | Control | vs | BCLP | 3.03586* | 0.646 | 1.187 | 4.885 | 0.000 |

| UCLP | 1.09561 | 0.595 | −0.608 | 2.799 | 0.683 | |||

| UCL | 0.56615 | 0.827 | −1.799 | 2.931 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLA | 0.83111 | 0.947 | −1.879 | 3.541 | 1.000 | |||

| BCLP | vs | UCLP | −1.94025* | 0.607 | −3.677 | −0.204 | 0.018 | |

| UCL | −2.46971* | 0.835 | −4.858 | −0.081 | 0.037 | |||

| UCLA | −2.20475 | 0.955 | −4.936 | 0.526 | 0.226 | |||

| UCLP | vs | UCL | −0.52946 | 0.796 | −2.807 | 1.749 | 1.000 | |

| UCLA | −0.2645 | 0.921 | −2.899 | 2.370 | 1.000 | |||

| UCL | vs | UCLA | 0.26496 | 1.085 | −2.838 | 3.368 | 1.000 | |

| TS-SF | Control | vs | BCLP | 1.76106* | 0.358 | 0.737 | 2.785 | 0.000 |

| UCLP | 0.92114 | 0.330 | −0.022 | 1.864 | 0.061 | |||

| UCL | 0.38968 | 0.458 | −0.920 | 1.699 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLA | 0.91857 | 0.525 | −0.582 | 2.419 | 0.825 | |||

| BCLP | vs | UCLP | −0.83992 | 0.336 | −1.801 | 0.122 | 0.138 | |

| UCL | −1.37138* | 0.462 | −2.694 | −0.049 | 0.037 | |||

| UCLA | −0.84249 | 0.529 | −2.355 | 0.670 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLP | vs | UCL | −0.53146 | 0.441 | −1.793 | 0.730 | 1.000 | |

| UCLA | −0.00257 | 0.510 | −1.461 | 1.456 | 1.000 | |||

| UCL | vs | UCLA | 0.52889 | 0.601 | −1.190 | 2.247 | 1.000 | |

| PClin-SF | Control | vs | BCLP | 1.50883* | 0.333 | 0.555 | 2.463 | 0.000 |

| UCLP | 0.76169 | 0.307 | −0.117 | 1.640 | 0.146 | |||

| UCL | 0.14194 | 0.426 | −1.078 | 1.362 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLA | 0.73527 | 0.489 | −0.663 | 2.133 | 1.000 | |||

| BCLP | vs | UCLP | −0.74714 | 0.313 | −1.643 | 0.149 | 0.186 | |

| UCL | −1.36690* | 0.431 | −2.599 | −0.135 | 0.019 | |||

| UCLA | −0.77356 | 0.492 | −2.182 | 0.635 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLP | vs | UCL | −0.61976 | 0.411 | −1.795 | 0.555 | 1.000 | |

| UCLA | −0.02642 | 0.475 | −1.385 | 1.333 | 1.000 | |||

| UCL | vs | UCLA | 0.59333 | 0.560 | −1.008 | 2.194 | 1.000 | |

| SM-SF | Control | vs | BCLP | 1.38651* | 0.348 | 0.392 | 2.381 | 0.001 |

| UCLP | 1.18991* | 0.320 | 0.274 | 2.106 | 0.003 | |||

| UCL | 0.58449 | 0.445 | −0.688 | 1.857 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLA | 1.05509 | 0.510 | −0.403 | 2.513 | 0.406 | |||

| BCLP | vs | UCLP | −0.19659 | 0.327 | −1.131 | 0.738 | 1.000 | |

| UCL | −0.80202 | 0.449 | −2.087 | 0.483 | 0.767 | |||

| UCLA | −0.33142 | 0.513 | −1.800 | 1.138 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLP | vs | UCL | −0.60542 | 0.428 | −1.831 | 0.620 | 1.000 | |

| UCLA | −0.13482 | 0.495 | −1.552 | 1.282 | 1.000 | |||

| UCL | vs | UCLA | 0.4706 | 0.584 | −1.199 | 2.140 | 1.000 | |

| TS-SA-SF-SP-PClin | Control | vs | BCLP | 24.94809* | 4.584 | 11.835 | 38.061 | 0.000 |

| UCLP | 16.41760* | 4.223 | 4.336 | 28.499 | 0.002 | |||

| UCL | 8.4768 | 5.863 | −8.295 | 25.249 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLA | 16.40092 | 6.718 | −2.819 | 35.621 | 0.161 | |||

| BCLP | UCLP | −8.53049 | 4.305 | −20.847 | 3.786 | 0.499 | ||

| UCL | −16.4713 | 5.922 | −33.414 | 0.471 | 0.063 | |||

| UCLA | −8.54716 | 6.770 | −27.915 | 10.821 | 1.000 | |||

| UCLP | UCL | −7.9408 | 5.648 | −24.097 | 8.216 | 1.000 | ||

| UCLA | −0.01667 | 6.531 | −18.702 | 18.668 | 1.000 | |||

| UCL | UCLA | 7.92413 | 7.694 | −14.087 | 29.935 | 1.000 | ||

* p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Discussion

Unique quality of this study is that five different groups of subjects were investigated. Only one study has been found based on literature search and used three groups of subjects of Saudi population. ST bridging, type of skeletal malocclusion, and associated dental anomalies at time in a single study have not been investigated before. All seven parameters of ST morphology (Hasan et al., 2016a,b, 2019; Islam et al., 2017) are investigated in this study. Previous studies measured three parameters of ST morphology and ST bridging only (Alkofide, 2008; Yasa et al., 2017).

A thorough knowledge of ST and its variations is very important to identify it from medically compromised patients such as spina bifida or craniofacial deviations (Axelsson et al., 2004). In a study by Alkofide (2008), the morphological variations of ST were assessed in CLP patients and it was found that most of the patients had morphological deviations such as irregular posterior wall and double contour of the floor as compared to normally formed ST. Second, in the NC subjects included in the study, the morphology of ST was normal as compared to the people with clefts. In the earlier study, it was shown that ST bridging was 5.5–22% in normal person, while it was 6.45% in the NC individuals. In the present study, it is 22.82% overall in the cleft patients. However, its occurrence was more in patients with craniofacial deviations. ST bridging was 30.77% in subjects with UCL in the present study. Under such circumstances, it draws attention and marks the direction for future research and study if ST bridge exists in normal individuals in the current population.

Various investigations have been done on the morphology of ST with varying techniques (Axelsson et al., 2004; Alkofide, 2008; Hasan et al., 2016a,b, 2019; Islam et al., 2017; Yasa et al., 2017). In the current study, no significant gender disparities of the ST morphology in all seven parameters were found. Taking into account the results of the current and the previous studies (Islam et al., 2017; Yasa et al., 2017), gender disparities were measurably insignificant for all linear and area measurements of ST. According to Weisberg et al. (1976), individuals with abnormal ST may suffer from undetected hidden disease. Hence, from an altered state of ST, pathology or anomaly can be identified that may influence the secretion of hormones such as growth hormone, prolactin, follicle stimulating hormone, and thyroid stimulating hormone (Alkofide, 2007).

The results revealed significant disparities in different parameters of the ST morphology in cleft subjects (BCLP, UCLP, UCLA, and UCL) as compared to the NC and also among different types of cleft subjects (BCLP, UCLP, UCLA, and UCL). BCLP subjects exhibited smaller measurements in all parameters compared to the other groups. Results revealed disparities in the measured three parameters of ST morphology are smaller (Alkofide, 2008) and larger (Yasa et al., 2017) between cleft subjects than in NC subjects. Alkofide (2008) found smaller measurements in UCLP subjects. Yasa at al. found larger values in all three measured parameters in cleft group, only length showed highly significant disparities, however, the type of cleft was not mentioned. In another study, data of 62 subjects with palatally impacted canine revealed significant disparities in ST bridging and three parameters of ST morphology as compared to the control in Saudi population (Baidas et al., 2018).

Studies in the past have shown that patients with disorders or syndromes such as holoprosencephaly (Kjær et al., 2002), Down syndrome (Hasan et al., 2019), spina bifida (Kjær et al., 1999), CLP (Alkofide, 2008; Yasa et al., 2017), fragile X syndrome (Kjær et al., 2001), Williams syndrome (Axelsson et al., 2004), and severe craniofacial deformities (Becktor et al., 2000) have craniofacial malformations which affect the size and/or morphology of ST.

It is well established that the anatomy of ST is variable, and it is of remarkable importance in orthodontics. The anterior form of ST may aid in predicting the patient growth and in surveying craniofacial morphology (Bishara and Athanasiou, 1995). An orthodontist should be aware of the normal variations in the ST which might help in identifying any pathology associated with it (Du Boulay and Trickey, 1967). The outcomes suggest that ST bridging and altered ST morphology in CLP subjects required careful monitoring of skeletal malocclusion, dental anomalies, and canine eruption are required to diagnosed and guide for better management at an early age.

Conclusion

ST bridging, type of skeletal malocclusion, and associated dental anomalies are common in cleft subjects compared to NC subjects. No significant gender disparities were found in four different types of cleft vs NC subjects. All seven parameters of ST morphology are smaller in NC subjects compared to those with clefts. BCLP subjects had smaller measurements in all seven parameters of ST morphology as compared to NC and all other types of cleft subjects.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Board of Alrass Dental Research Center, Qassim University. Ethical clearance has been obtained with the Code #: DRC/009FA/20. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2020.00656/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alam M. K., Iida J., Sato Y., Kajii T. S. (2013). Postnatal treatment factors affecting craniofacial morphology of unilateral cleft lip and palate (UCLP) patients in a Japanese population. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 51 e205–e210. 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkofide E. (2007). The shape and size of sella turcica in skeletal class I, class II, and class III Saudi subjects. Eur. J. Orthod. 29 457–463. 10.1093/ejo/cjm049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkofide E. A. (2008). Sella turcica morphology and dimensions in cleft subjects. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 45 647–653. 10.1597/07-058.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson S., Storhaug K., Kjaer I. (2004). Post-natal size and morphology of the sella turcica. Longitudinal cephalometric standards for Norwegians between 6 and 21 years of age. Eur. J. Orthod. 26 597–604. 10.1093/ejo/26.6.597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baidas L. F., Al-Kawari H. M., Al-Obaidan Z., Al-Marhoon A., Al-Shahrani S. (2018). Association of sella turcica bridging with palatal canine impaction in skeletal Class I and Class II. Clin. Cosmet Investig Dent. 10 179–187. 10.2147/ccide.s161164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becktor J. P., Einersen S., Kjaer I. (2000). A sella turcica bridge in subjects with severe craniofacial deviations. Eur. J. Orthod. 22 69–74. 10.1093/ejo/22.1.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishara S., Athanasiou A. (1995). “Cephalometric methods for assessment of dentofacial changes,” in Orthodontic Cephalometry, ed. Athanasiou A. E. (St Louis, MO: Mosby-Wolfe; ), 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- Celik-Karatas R. M., Kahraman F. B., Akin M. (2015). The shape and size of the sella turcica in turkish subjects with different skeletal patterns. Eur. J. Med. Sci. 2 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. E., Ratay J. S., Marazita M. L. (2006). Asian oral-facial cleft birth prevalence. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 43 580–589. 10.1597/05-167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Boulay G., Trickey S. (1967). The choice of radiological investigations in the management of tumours around the sella. Clin. Radiol. 18 349–365. 10.1016/s0009-9260(67)80035-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque S., Alam M. K. (2015). Common dental anomalies in cleft lip and palate patients. Malays J. Med. Sci. 22 55–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan H. A., Alam M. K., Abdullah Y. J., Nakano J., Yusa T., Yusof A., et al. (2016a). 3DCT morphometric analysis of sella turcica in Iraqi population. J. Hard. Tissue Biol. 25 227–232. 10.2485/jhtb.25.227 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan H. A., Alam M. K., Yusof A., Mizushima H., Kida A., Osuga N. (2016b). Size and morphology of sella turcica in Malay populations: a 3D CT study. J. Hard. Tissue Biol. 25 313–320. 10.2485/jhtb.25.313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan H. A., Hameed H. A., Alam M. K., Yusof A., Murakami H., Kubo K., et al. (2019). Sella turcica morphology phenotyping in Malay subjects with down’s syndrome. J. Hard. Tissue Biol. 28 259–264. 10.2485/jhtb.28.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M., Alam M. K., Yusof A., Kato I., Honda Y., Kubo K., et al. (2017). 3D CT study of morphological shape and size of sella turcica in Bangladeshi population. J. Hard. Tissue Biol. 26 1–6. 10.2485/jhtb.26.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær I., Fischer Hansen B., Reintoft I., Keeling J. (1999). Pituitary gland and axial skeletal malformation in human fetuses with spina bifida. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 9 354–358. 10.1055/s-2008-1072282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær I., Hjalgrim H., Russell B. G. (2001). Cranial and hand skeleton in fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 100 156–161. 10.1002/ajmg.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær I., Keeling J. W., Fischer H. B., Becktor K. B. (2002). Midline skeletodental morphology in holoprosencephaly. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 39 357–363. 10.1597/1545-1569_2002_039_0357_msmih_2.0.co_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars M., Houston W. J. (1990). A preliminary study of facial growth and morphology in unoperated male unilateral cleft lip and palate subjects over 13 years of age. Cleft Palate J. 27 7–10. 10.1597/1545-1569_1990_027_0007_apsofg_2.3.co_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbagh H. J., Innes N. P., Sallout B. I., Peter A. M., Nasir A., Al-Khozami A. I., et al. (2015). Birth prevalence of non-syndromic orofacial clefts in Saudi Arabia and the effects of parental consanguinity. Saud. Med. J. 36 1076–1083. 10.15537/smj.2015.9.11823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg L. A., Zimmerman E. A., Frantz A. G. (1976). Diagnosis and evaluation of patients with an enlarged sella turcica. Am. J. Med. 61 590–596. 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90136-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasa Y., Bayrakdar I. S., Ocak A., Duman S. B., Dedeoglu N. (2017). Evaluation of sella turcica shape and dimensions in cleft subjects using cone-beam computed tomography. Med. Princ. Pract. 26 280–285. 10.1159/000453526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.