Abstract

Achalasia is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by failure of relaxation of the LES and altered motility of the esophagus. Traditional surgical approach to relieve the obstruction at the LES includes cardiomyotomy is highly effective. Fundoplication is added to decrease the risk of postoperative reflux. Per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM)is a new endoscopic procedure that allows division of the LES via transoral route. It has several advantages including les invasiveness, cosmesis and tailored approach to the length on the myotomy. However, it is associated with increased rate of postprocedural reflux. Various endoscopic interventions can be used to address this problem. New POEM plus fundoplication (POEM+F) technique was recently introduced into clinical practice to specifically address this problem.

Keywords: Achalasia, Gastroesophageal junction, Cardiomyotomy, Heller myotomy, Peroral endoscopic myotomy

Introduction

Achalasia is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive loss of normal function of the esophageal smooth muscle. Loss of ganglion cells of the myenteric plexus of the esophagus causes uncoordinated esophageal motility resulting in the failure of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation, accompanied by various alteration of normal peristalsis of the smooth muscle of the esophagus (Fig. 1 A, B.). The cause of primary achalasia remains unknown. Secondary causes include infections, autoimmune disorders, and malignancy. Clinical manifestations of achalasia include dysphagia to solids and liquids, regurgitation, substernal chest pain, leading in extreme cases to weight loss and malnutrition. Reflux is not characteristic for achalasia due to obstruction of the GEJ by a hypertonic LES, however, stasis and fermentation of the retained food and secretions lead to frequent heartburn in these patients. Although restoration of normal esophageal function is impossible at present, over the last century a variety of treatments were introduced into clinical practice for the management of this chronic disease, aiming at palliation of symptoms by obliterating the lower esophageal sphincter and relieving the obstruction. This chapter will touch upon the endoscopic and surgical treatments of achalasia.

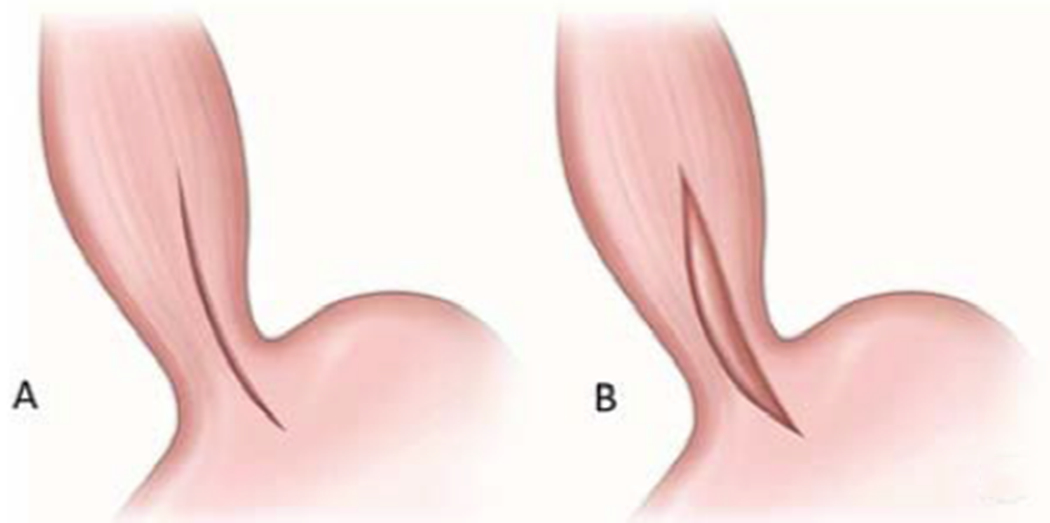

Figure 1.

Gastroesophageal junction. A. Normal anatomy. B. Achalasia. Due to failure of LES to relax there is an obstructive physiology, leading to proximal esophageal dilation and tortuosity.

History of Surgical therapy for achalasia

A landmark publication on the topic occurred in 1914 when German physician Ernst Heller (1877 – 1964) published the first report on esophagocardiomyotomy as a way of relieving dysphagia in case of achalasia (1). Initially confronted with disbelief that an extramucosal myotomy could correct impaired esophageal function, the operation proved to be incredibly effective in alleviating symptoms and complications of achalasia. The procedure, that took place on April 14, 1913, was an extramucosal esophagomyotomy on a 49-year-old man with a 30-year history of dysphagia. In Heller’s original report, he quoted then-recent publication by Heyrovsky describing success with side-to-side esophagogastrostomy, bypassing the spastic lower esophageal sphincter (2).

During the conduct of the procedure, Heller abandoned his initial plan of performing a side-to-side anastomosis by Heyrovski and instead performed the transabdominal double vertical extramucosal esophagomyotomy. The procedure was a huge success with an immediate and durable resolution of the dysphagia. The patient resumed full oral intake the next day after the surgery, maintaining good health and nutrition at 8 years follow-up (3). According to Heller, Gottstein first expressed the concept of extramucosal myotomy in 1901, theorizing that a procedure similar to a pyloromyotomy could be performed at the gastric cardia. However, despite this early theoretical speculation, an esophagomyotomy was not performed in practice until Heller (3, 4). Despite introducing a variety of other contemporary procedures for achalasia extramucosal cardiomyotomy has rapidly gained wide acceptance, becoming a standard of care, while other operations of esophagogastrostomy fell out of favor mainly due to side effects from regurgitation of gastric contents and subsequent severe esophagitis(5–9).

For decades, since this initial description, surgical therapy has remained the gold standard of achalasia treatment, as medical therapy failed to provide substantial and sustainable relief. Currently, medical therapy is reserved for poor surgical candidates unable to tolerate invasive procedures. Medications include nitrates, calcium channel blockers, and other agents such as sildenafil, atropine, terbutaline, and theophylline. The premise of medical therapy is to relax the smooth muscle of the lower esophageal sphincter to reduce the lower esophageal sphincter pressure and dysphagia, although clinical applications have been limited secondary to systemic side effects.

For these reasons endoscopic and surgical therapy of achalasia prevails and the role of pharmacologic treatment for esophageal achalasia is limited particularly to early-stage disease, high surgical risk elderly patients, failed treatments after botulinum toxin injection, or for the temporary bridging of symptoms in patients waiting for definitive therapy. This is especially evident now with the recent development of new minimally invasive surgical and endoscopic interventions being introduced into clinical practice for the management of achalasia (10–12)

Surgical therapy for achalasia

After Heller’s initial description, open extramucosal esophagomyotomy for many years had remained the principal therapy for achalasia. Although the procedure enjoyed overall excellent results with few complications, a traditional open approach via either a thoracotomy or a laparotomy required a prolonged hospital stay, delayed recovery, and elevated levels of surgical pain (13).

With the advent of minimally invasive technology in 1980s-90s, the laparoscopic approach was rapidly adopted in foregut surgery. Just a few years after the laparoscopic cholecystectomy was widely being performed, in 1991 a group led by Cushieri reported on the first experience of laparoscopic cardiomyotomy in a single patient with manometrically confirmed achalasia. The patient enjoyed complete relief of dysphagia postoperatively with minimal postoperative discomfort and required only 3 days of hospital stay – a significant advantage over the traditional open approach (14). This procedure was introduced in the US by Pellegrini et al. In 1992 authors published their results of a minimally invasive esophagomyotomy (13). They approached the gastroesophageal junction through the left chest rather than through a transabdominal approach. The authors operated on 17 patients with radiographically confirmed achalasia with success of the thoracoscopic approach in 15 patients. In 2 patients, a second laparoscopic procedure was required likely due to the incomplete myotomy secondary to limited extension onto the gastric cardia via the chest. Authors believed that the thoracoscopic approach had an advantage of less disruption of the elements of the antireflux mechanism reducing the incidence of postoperative gastroesophageal reflux, obviating the need for an antireflux procedure. Authors postulated that the laparoscopic Heller myotomy should be reserved only for patients with previously failed thoracoscopic myotomy or “hostile” chest with previous surgical intervention (13). However, in a follow-up publication on the topic reporting on their 8-year experience, the group demonstrated a 60% incidence of gastroesophageal reflux after the thoracoscopic procedure as opposed to 17% after laparoscopic myotomy with fundoplication. Clearly, with the experience, the authors switched their preference where only 35 patients had thoracoscopy with the majority of patients (133 of 168) underwent laparoscopic cardiomyotomy with the fundoplication (15). They cited 3 main advantages of the laparoscopic approach with the fundoplication: more effective relief of dysphagia, shorter hospital stay, and significantly decreased postoperative reflux, declaring it the primary treatment modality for esophageal achalasia (15).

Relieving obstruction in achalasia patients via anatomic disruption of the lower esophageal sphincter with cardiomyotomy leads to substantial gastroesophageal reflux (Fig. 2 A, B.). With increasing volume of Heller myotomies being performed laparoscopically, a great deal of controversy was raised regarding the role of an antireflux procedure after a cardiomyotomy for control of reflux. In a meta-analysis of 21 studies on laparoscopic Heller Myotomy with and without antireflux procedure from 1991 to 2001, Lyass et al did not observe any difference in pathologic acid exposure between these two patient groups making no recommendation regarding the role of antireflux in this patient population (16). However, in a prospective double-blind trial randomizing 43 patients with achalasia by Richards et al. demonstrated a substantial decrease in pathologic reflux in combined procedure with Heller myotomy and Dor fundoplication (Fig. 3 C.) versus Heller myotomy alone. Six months postoperatively, 24-hr pH demonstrated a decrease in reflux from 47.6% (10 of 21 patients) after Heller myotomy alone to 9.1% (2 of 22 patients) with the combined approach, laying the ground for standardization of adding fundoplication to cardiomyotomy (17).

Figure 2.

Heller cardiomyotomy. A. placement of the incision across the LES. B. Completed myotomy with disruption of the lower esophageal sphincter.

Figure 3.

Types of fundoplication. A. Nissen fundoplication. B. Toupet fundoplication. C. Dor fundoplication.

In a follow-up publication to address the shortcoming of limited time observation, authors analyzed the long-term (mean of 11.8 years) results on the same patient cohort (18). In the analysis, 27 of the original 41 patients (66%) were studied on the patient-reported measures of dysphagia and gastroesophageal reflux utilizing the Dysphagia Score and the Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Health-Related Quality of Life (GERD-HRQL) questionnaires. The authors demonstrated that Dysphagia Scores and GERD-HRQL scores were slightly worse but not statistically significant for the Heller Myotomy alone group versus combined procedure of the myotomy with fundoplication. With this long-term follow-up, the majority of patients’ post-treatment still required dietary modifications and anti-reflux medications and about 40% of participants required additional endoscopic interventions for dysphagia. One patient in each group required redo Heller myotomy ultimately followed by esophagectomy. Authors concluded that long-term patient-reported outcomes between the two interventions were comparable (19). It is likely that due to the limited number of patients, this study was underpowered and failed to demonstrate the difference between these groups.

Despite convincing evidence of benefits of the fundoplication drawn from Richards et al trial, increasing controversy persisted as to the preferred type of fundoplication after cardiomyotomy. In a review of over five thousand patients from 75 papers, the mean incidence of symptomatic reflux was demonstrated at 8.6% (20). The most commonly performed antireflux procedures were the anterior 180-degree Dor fundoplication and the 360-degree Nissen fundoplication (Fig. 3 C, A.). However, the concern surrounding the Nissen procedure was the risk of obstructive physiology with a complete circumferential wrap in the aperistaltic esophagus. (21).

This concern was proven true in a prospective randomized trial, comparing long-term outcomes of Dor versus floppy-Nissen fundoplication after laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia. After excluding 9 patients in the initial cohort of 153 patients, 144 patients were randomized to one of the two treatment groups. With a mean follow-up of 125 months, there were no differences in clinical (5.6% vs. 0%) or instrumental (2.8% vs. 0%) rates of gastroesophageal reflux. However, patients undergoing Nissen fundoplication had significantly higher rates of dysphagia (2.8% vs. 15%). Authors supported the use of the Dor fundoplication as the preferred method of reflux control in achalasia patients after Heller myotomy (21).

With this data suggesting better functional outcomes with a partial wrap for reflux control, further discussion centered on the use of a posterior (Toupet) versus an anterior (Dor) fundoplication (Fig. 3 B, C.). The potential disadvantage of a posterior approach would be the angulation of the gastro-esophageal junction, hypothetically creating an impediment to the bolus passage and extensive retroesophageal dissection, potentially leading to induction of reflux (22). However, evidence from gastroesophageal reflux disease literature suggested an advantage of posterior partial fundoplication for reflux control. Such, in a randomized controlled trial comparing the anterior and posterior laparoscopic partial fundoplications in 95 patients with GERD reflux control was better after the posterior fundoplication. In this group of patients during the first postoperative year acid exposure was significantly lower in Toupet group in comparison to Dor group(23).

Several subsequent studies comparing the efficacy of an anterior versus posterior partial fundoplication after a cardiomyotomy has produced conflicting results, essentially leaving the choice of fundoplication to the individual surgeon’s preferences (22, 24). In the first randomized trial comparing Dor versus Toupet fundoplication after laparoscopic Heller myotomy, 60 patients were assigned to these two approaches. Postoperatively, reflux was assessed with 24-hr pH monitoring at 6 and 12 months. Abnormal acid reflux was reported in 41.7% of the Dor group versus 21.1% of the Toupet group; however, the differences were not statistically significant (24). In another trial, 42 patients with newly diagnosed achalasia were randomized to undergo either a Toupet or a Dor fundoplication following a classical open or laparoscopic cardiomyotomy. Results were assessed during the first postoperative year with Eckardt scores, EORTC QLQ-OES18 scores, HRQL questionnaires, barium esophagram, and ambulatory 24-hr pH monitoring. The analysis showed dramatic improvement of Eckardt scores with both procedures, but the EORTC QLQ-OES18 scores and esophageal emptying were significantly better in the Toupet group, yet, no differences were observed in HRQL evaluations or 24-hr pH monitoring (22).

In another prospective randomized trial of 73 patients with achalasia with either Dor or Toupet fundoplication after laparoscopic Heller myotomy, postoperative high-resolution manometry at 6 and 24 months showed similar lower esophageal pressure patterns with both procedures. Notably, abnormal acid exposure was significantly lower in Dor (6.9%) as opposed to Toupet patients (34%) at 6 months, but equivalent at 12 or 24 months. Nevertheless, there was no difference in postoperative symptom scores at 1, 6, or 24 months. Authors again left the choice of the procedure to the surgeon’s preferences, concluding the choice of fundoplication doesn’t affect the long-term outcome (25). A retrospective study of 97 patients comparing long-term rates of dysphagia, reflux symptoms, and patient satisfaction between the anterior versus posterior approach also showed effective resolution of the dysphagia with both procedures (89% Toupet vs. 93% Dor) but substantially higher reflux rates with anterior fundoplication (11% after Toupet versus 35% after Dor fundoplication’ p<0.05), although, overall patient satisfaction was 88% in both groups (26).

Robotic surgery was a logical evolution of minimally invasive surgery with computer-enhanced technology (Fig. 4.). Improved binocular visualization, tremor filtration, instrument articulation, and other embedded safety features potentially conveying an outcome benefit. Several studies reported on the outcomes of a robotic versus a laparoscopic Heller myotomy. A retrospective multicenter trial involving 121 patients demonstrated similar operative outcomes and operative times between the two approaches. There was, however, decreased incidence of intraoperative esophageal mucosal perforations with the use of the surgical robot (0% vs. 16%). Both patient groups did well with 92% versus 90% relief of their dysphagia at 18 and 22-month follow-ups (27). Similarly, in another study of 61 patients, a lower rate of esophageal perforations and a better quality of life based on the Short Form (SF-36) Health Status Questionnaire and disease-specific gastroesophageal reflux disease activity index (GRACI) were demonstrated in the robotic group (28). A meta-analysis, published in 2010 concluded that the risk of perforation is lower in robotic myotomy (29). Although results are overall positive in these studies in favor of a robotic approach, most authors compared robotic outcomes with earlier laparoscopic procedures and a learning curve may have been attributable for the difference.

Figure 4.

DaVinci Xi robot docket for Heller myotomy procedure

Endoscopic therapy for achalasia

The results of pharmacological treatments for achalasia including botulinum toxin injection have been relatively unsupported and are only recommended to patients unfit for interventions under general anesthesia (11, 12). The first randomized control study, comparing laparoscopic cardiomyotomy and fundoplication to botulinum toxin injections in patients with esophageal achalasia demonstrated that while at 6 months the results in the 2 groups were comparable, at 12 months, symptom recurrence in the Botox group was 40% versus 13% in the surgical group (30). Authors concluded that laparoscopic myotomy is safe, offering better and longer lasting symptomatic control over serial botulinum toxin injections, reserving the latter to patients unfit for surgery or as a bridge to surgical management.

Endoscopic pneumatic dilation until recently was considered the most effective nonsurgical treatment of achalasia (Fig. 5 A, B and C.) (31). Pneumatic dilators are preferred over rigid dilators as they not only stretch but also produce disruption of the LES muscle fibers. Varying rates of success are reported in the literature. Post-dilation symptom free rates range from 40-78% at 5 years to 12-58% at 15 years (32). Even some authors have reported success rates at 5 years to be up to 97% and 93% at 10 years with repeat on-demand dilatations, although it is generally accepted that sustainable long-term results cannot be expected from this therapy (31). Predictors of treatment failure include younger patients less than 40 years, presence of pulmonary symptoms, and failure to respond to the initial dilation treatment. Complications from esophageal dilation include esophageal perforation, intramural hematoma, and gastroesophageal reflux. In a meta-analysis of 1065 patients treated by experienced physicians, esophageal perforations occurred in 1.6% of patients. Up to 40% of patients developed active and even ulcerated esophagitis after serial dilations, likely due to uncontrolled reflux although only 4% were symptomatic. Endoscopic pneumatic dilation currently is considered the most effective therapy among non-operative treatment choices, but is associated with a high risk of complications and should be considered in select patients who refuse surgery or are poor operative candidates (31).

Figure 5.

Pneumatic dilation of the gastroesophageal junction. A. Placement of the balloon across the gastroesophageal junction. B. Inflation of the balloon, leading to the disruption of the fibers of the LES. C. Relieved obstruction of the LES.

Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM)

As a new development in the therapy for achalasia, in 2008, Inoue et al introduced a concept of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) for the treatment of achalasia (33), with the acronym of POEM which stood for “Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy”. In 2010, the authors published their first series of peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for the treatment of achalasia (34). All cases of achalasia were considered for POEM including tortuous dilated sigmoid esophagus, which is considered a relative contraindication to surgical myotomy. POEM could also be performed in patients that have failed previous therapies such as botulinum toxin injection, pneumatic dilation, or Heller myotomy.

The standard POEM procedure consists of four sequential steps: 1- mucosal incision, 2 - submucosal tunneling, 3 - myotomy itself and 4 - closure of the mucosotomy defect (Figure 6 A, B, C and D.). A 2 cm mucosal incision is made after creating a submucosal cushion with saline and blue dye mixture, providing entrance to the submucosal space. Subsequently, performing the submucosal dissection, which extends 3 cm distal to the gastroesophageal junction, creates the submucosal tunnel. Once the tunnel has been completed, the myotomy is performed, starting 3 to 5 cm distally to the site of mucosotomy. The length of the myotomy may be adjusted depending on the achalasia subtype. Next, after a careful inspection of the mucosa for any inadvertent mucosal injuries, closure of the mucosotomy is performed with either endoscopic hemostatic clips or the endoscopic suturing (i.e. Overstitch, Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, Tx) (35).

Figure 6.

Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) Procedure. A. Mucosotomy and initial submucosal entry. B. Dissection of the submucosal tunnel. C. Division of the esophageal muscle (myotomy). D. Closure of the mucosotomy.

From a procedural perspective, POEM offers a significant advantage by adapting the extent and location of the myotomy according to patients’ specific characteristics and the type of the achalasia (35). The impact of the differential length of the myotomy in the different types of achalasia was studied by Kane et al. The group reported utilizing high-resolution esophageal manometry (HREM) in forty POEM cases to define myotomy length. The authors found significantly improved postoperative Eckardt scores in the group with tailored (longer) myotomy length in patients with subtype III achalasia (36).

Since its advent, the POEM procedure has enjoyed rapid and wide adoption worldwide becoming the primary and preferred treatment of achalasia with thousands of procedures performed since its initial description. Data from largely single-center studies and small case series suggest that POEM is a safe alternative to Heller myotomy. POEM was popularized in the United States by Swanstrom et al who published the first report in 2012 with results of this technique in 18 patients with esophageal achalasia (37). At a mean follow-up of 11 months, all patients had excellent outcomes, with a median Eckardt score of 0 (range 0-3). Endoscopy proven esophagitis was observed in 28% of patients, while pH monitoring demonstrated pathologic reflux in 46%. In an international multicenter study involving 70 patients at 12 months, 82% were in remission with esophagitis shown in 42% of patients after POEM (38). In an analysis of 94 patients after POEM at a mean follow-up of 11 months, excellent results were observed in 94.5% with postoperative pH monitoring displaying pathologic reflux in 53.4% of patients (39). Analysis of outcomes of 80 patients with achalasia at a mean follow-up of 29 months revealed a success rate of 77.5% with esophagitis present in 37.5% of patients (40).

Despite its wide success, the safety of the POEM procedure is still debated. This question was addressed in a large retrospective multicenter review of adverse events from 12 centers, including almost two thousand patients. The study demonstrated low overall prevalence of any adverse events, such as inadvertent mucosotomy, esophageal leak, complications related to insufflation, submucosal hematoma, and cardiopulmonary complications at 7.5% (156 events in 137 patients). Majority of the adverse events were mild in 6.4% cases with only 0.5% being severe. The most common adverse event in this study was an inadvertent mucosotomy, which occurred in 51 (2.8%) patients. Sigmoid-type esophagus, triangular tip knife, an inexperienced operator (<20 cases performed), and non-spray coagulation were significant predictors of adverse event occurrences (35). It is also noteworthy to mention that the wide range of reported complication rates with POEM (0 to 72%) is mainly attributable to the lack of consensus on terminology in the literature. For instance, whereas some authors report asymptomatic gas-related events, such as subcutaneous emphysema, pneumoperitoneum, pneumothorax, or mediastinal emphysema as an incidental finding others give them a grading of a full adverse event (35, 41).

Since its inception, the POEM procedure has frequently been compared to other well-established modalities for the treatment of achalasia. In a randomized controlled trial of 133 patient with achalasia treatment success was observed in 92% of POEM patients vs 54% after pneumatic dilation. Two serious adverse events, including one perforation occurred after pneumatic dilation, while none in the POEM group (42). In another retrospective study, comparing outcomes of 71 patients with newly diagnosed achalasia undergoing POEM or pneumatic dilation, POEM demonstrated a durable effect, while the effect of pneumatic dilation progressively decreased starting at 6 months (43). While the difference was demonstrated in all 3 subtypes of achalasia, statistical significance was only reached in type III achalasia.

Gastroesophageal reflux after POEM

Postoperative gastroesophageal reflux remains a concern after any type of myotomy for achalasia due to mechanical disruption of the lower esophageal sphincter. As the basis of the POEM procedure is identical to the Heller myotomy, post POEM gastroesophageal reflux has been naturally reported. In a retrospective case-control study of 282 patients that aimed to identify the prevalence of reflux after POEM, clinical success was demonstrated at 94%. At a median follow-up of 12 months, an abnormal DeMeester score was reported in 58%, with reflux esophagitis present in 23% upon upper endoscopy. Despite that, reflux was asymptomatic in the majority of patients (60%) (44).

The comparative Incidence of postoperative gastroesophageal reflux between the standard of care – laparoscopic or robotic Heller myotomy and POEM was assessed in a systematic review and meta-analysis including almost eight thousand patients from 74 published reports. Primary outcomes were the improvement of the dysphagia and the rate of postoperative gastroesophageal reflux. Analysis demonstrated symptomatic improvement in dysphagia in 93.5% for POEM and 91% for laparoscopic Heller myotomy at twelve moths and 92.7% versus 90.0% at 24 months respectively. However, POEM patients were more likely to develop gastroesophageal reflux (OR 1.69), erosive esophagitis (OR 9.31) and abnormal pH monitoring values (OR 4.30) (45).

Although POEM is associated with increased rates of reflux and acid exposure it is successfully managed with long-term PPI use in the majority of cases. Given the known association between long-standing GERD, Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma as well as the increasing adverse effects of long-term PPI use, high incidences of post-procedural esophageal acid exposure is a significant concern (46–49). In previously published randomized control trials, TIF has shown superiority over high-dose medical therapy in reliving GERD symptoms with efficacy rates comparable to surgical Nissen fundoplication (50–52). Recently a case series of transoral incisionless fundoplication (TIF) for management of post-POEM GERD was presented – a logical adjunct to the POEM procedure, allowing to keep patients in the realm of endoscopic therapy, while definitively addressing the reflux. Authors demonstrated a 100% success rate with discontinuation of proton pump inhibitor therapy in all 5 presented patients and resolution of all cases of esophagitis with mean follow-up time of 27 months (53).

Although surgical Heller myotomy achieves high success and low complication rates, in cases of procedure failure, performing a redo Heller myotomy is a tedious and complex procedure (54). POEM has been reported as a successful rescue endoscopic therapy for patients who have had failed previous Heller operation. In a case series of 8 patients with recurrent dysphagia after failed Heller myotomy, 3 patients underwent redo laparoscopic Heller myotomy with fundoplication and 5 patients underwent redo myotomy with POEM. All patients achieved significant improvement in symptoms and Eckardt scores at an average follow-up of 5 months (55). In a retrospective cohort study of 180 patients with achalasia who underwent a POEM at 13 tertiary care centers worldwide, technical success rates were demonstrated at 98% in prior Heller myotomy group and 100% in non-Heller myotomy group. However, a significantly lower proportion of patients in the Heller myotomy group achieved clinical success (81%) than in the non-Heller myotomy group (94%), suggesting other etiologies for failure. There were no significant differences in rates of adverse events and symptomatic reflux between the two groups (41). In another publication, POEM after failed Heller was performed in 46 patients with 100% technical success rate and 85% clinical success rate; 8 (17%) patients developed adverse events, all managed endoscopically without surgical conversion (56). In a systematic review of 289 patients requiring repeat intervention after previous Heller myotomy, 36 patients were treated with POEM. Analysis demonstrated a technical success rate in excess of 98% with a 39% rate of insignificant adverse events (57). An important feature of the POEM procedure is an ability to localize the myotomy in any aspect of the esophageal wall, frequently away from the previous plane of dissection – an advantage frequently unavailable in the redo laparoscopic approach

Chronic and End-stage Achalasia

Persistent obstruction of the GEJ with chronic retention of a food bolus leads to progressive dilation and elongation of the esophagus leading to a sigmoid appearance in end-stage achalasia (Figure 7 A, B and C.). Even with modern therapy, esophageal function will deteriorate over time in 10-15% of individuals with achalasia, and up to 5% will develop end-stage achalasia with sigmoidal features (58). Some authors have recommended a surgical myotomy for the primary treatment of sigmoid esophagus, reserving esophagectomy for patients with failure of surgical myotomy, whereas others prefer primary esophagectomy. The appropriate surgical intervention for sigmoidal esophagus in the setting of chronic achalasia remains controversial (59). In a retrospective analysis of minimally invasive myotomy (MIM) and minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) in the treatment of 30 patients with sigmoidal esophagus, 24 (80%) patients had undergone MIM and only 6 (20%) patients proceeded straight to MIE. There was no mortality with a median hospital stay of 2 days for MIM and 7 days for MIE. At a mean follow-up of 30 months, 9 patients (37.5%) had failed MIM and required either redo myotomy in 1 case (11%) or an esophagectomy in the rest of the 8 patients (89%). Analysis revealed that previous myotomy, younger age (mean 53 years versus 66 years in MIM success), and duration of symptoms (mean 25 years) were significant predictors of failure of MIM (60). Currently, there is no randomized data available to definitively establish indications for primary MIM or MIE in the setting of advanced achalasia with sigmoid esophagus (58).

Figure 7.

End stage achalasia. A. Esophagram of the patient with megaesophagus with dilation and tortuosity of the entire organ. B. Esophagram of the patient with proximal megaesophagus and distal corkscrew appearance of the type III achalasia. C. Axial CT image of the patient with megaesophagus. D. Coronal reconstruction image of the patient with megaesophagus.

Esophagogastrostomy is an alternative to myotomy procedure, establishing an anastomosis in end stage achalasia between the dilated esophagus and the stomach to relieve the obstruction. The first description of the technique of an esophagogastrostomy in the care of end-stage achalasia was published over a century ago (2, 6). It all but disappeared from the clinical practice due to unacceptably high rate of reflux complications. Laparoscopic-stapled cardioplasty – a modern adaptation of this open technique in the case series of 7 patients with persistent achalasia were recently published. All but one patient had successful resolution of symptoms, with 4 patients developing post procedure reflux, which was controlled with chronic PPI use (61). A similar procedure was reported in another series of 3 individuals with end-stage type IV achalasia. All patients had significant improvement in their symptoms and two required chronic PPI therapy for reflux postoperatively (58).

POEM has also effectively been applied for the treatment of end-stage achalasia. All major series reporting on the POEM procedure include a subset of patients with end-stage achalasia that were successfully treated. In the report of 32 consecutive patients with sigmoid type achalasia, technical success was achieved in all patients with a treatment success rate of 96.8% at a 30-month average follow-up with a significant decrease in LES pressure and Eckardt scores. Authors noted that morphological changes of the esophagus made endoscopic tunneling more challenging and time-consuming but did not prevent successful POEM. Clinical reflux was observed in 25.8% of these patients post procedure (62).

Achalasia: A Risk Factor for Carcinoma

Currently, there are no generally accepted recommendations on follow-up for patients with achalasia. The real burden of achalasia at the malignancy genesis is still a controversial issue (63). There have been several factors leading to an increased risk of esophageal carcinoma in achalasia patients. Continuous chemical irritation due to saliva and food decomposition in the esophagus could induce chronic hyperplastic esophagitis, dysplasia, and eventually carcinoma. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11,978 achalasia patients from 40 selected studies, the absolute risk increase was 308.1 cases for squamous cell carcinoma and 18.03 cases for adenocarcinoma per 100,000 patients per year. This data potentially makes an even stronger argument for performing a fundoplication after myotomy, to avoid reflux and Barrett’s esophagus - a known risk factor for carcinogenesis (63).

Future Direction

With peroral endoscopic myotomy becoming the minimally invasive endoscopic treatment of choice for achalasia, the problem of gastroesophageal reflux post-POEM have been heightened (44, 64). In 2019, Inoue et al reported their first experience of combined endoscopic fundoplication added to the standard POEM procedure (POEM + F). The post-POEM fundoplication consisted of three steps: entry into the peritoneal cavity, distal and proximal anchoring of the endoloop with clips, and closure of the endoloop. The fundoplication was technically feasible in all 21 cases. No immediate or delayed complications occurred. The partial rotation and traction of the anterior gastric wall towards the gastroesophageal junction created a visually identifiable wrap that mimicked a surgical partial fundoplication (Fig. 8 A, B and C.). Acknowledging limited experience, authors believe that POEM+F may help mitigate the post-POEM incidence of GER and serve as a minimally invasive endoscopic alternative to the surgical Heller-Dor procedure (64).

Figure 8.

Endoscopic fundoplication step of the POEM+F procedure by Inoue et al. A. Peritoneal cavity entry. B. Anchoring of the endoloop with endoclips. C. Closure of the endoloop with creation of the fundoplication.

Lower esophageal sphincter (LES) electrical stimulation has been described to improve GERD symptoms and reduce esophageal acid exposure while enhancing the LES tone without impairing relaxation (65, 66). In 2015, Rodriguez et al reported the first clinical use of electrical LES stimulation in the care of post-POEM GERD not responsive to PPI use. In this case report, patients had a significant reduction of GERD-HRQL reflux (26 vs. 7), regurgitation scores (24 vs. 3), and a reduced total number of reflux episodes (82 vs. 14) 3 months after implantation of the device (65).

Another possible alternative therapeutic approach is the transplantation of neural progenitor cells. Researchers have demonstrated that stem cells with neurogenic potentiation can successfully survive, migrate, and differentiate into neurons and glia within the aganglionic organ. There has been preliminary evidence indicating that transplanted cell-based therapies can lead to a functional recovery of aganglionic disease such as esophageal achalasia, although no strong evidence has been reported (67).

CONCLUSION

Achalasia has featured a century-long history of ever evolving surgical therapy, with myotomy remaining the main stay management modality. Heller myotomy, currently performed laparoscopically or robotically offers successful relief of the obstruction in achalasia patient. Fundoplication is currently routinely added to surgical myotomy to decrease incidence of the postoperative reflux. POEM is a new endoscopic technique and is being rapidly adopted into clinical practice. High rates of post POEM reflux can be addressed with either medical therapy or other endoscopic procedures. Recently introduced POEM+F procedure holds promise as a potentially future procedure of choice. Despite long history of such challenging problem as achalasia, recent developments in minimally invasive techniques offer new hope for patients with better outcomes, faster recovery, and most importantly improved long-term functional results.

Key points.

Achalasia is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by failure of relaxation of the LES and altered motility of the esophagus.

Traditional surgical approach to relieve the obstruction at the LES includes cardiomyotomy is highly effective.

Fundoplication is added to decrease the risk of postoperative reflux. Per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM)is a new endoscopic procedure that allows division of the LES via transoral route.

It has several advantages including les invasiveness, cosmesis and tailored approach to the length on the myotomy. However, it is associated with increased rate of postprocedural reflux. Various endoscopic interventions can be used to address this problem.

New POEM plus fundoplication (POEM+F) technique was recently introduced into clinical practice to specifically address this problem.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Romulo A. Fajardo, Department of General Surgery, Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3401 N Broad St, C-401, Philadelphia, PA 19140.

Roman V. Petrov, Department of Thoracic Medicine and Surgery, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3401 N Broad St, C-501, Philadelphia, PA 19140.

Charles T. Bakhos, Department of Thoracic Medicine and Surgery, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3401 N Broad St, C-501, Philadelphia, PA 19140.

Abbas E. Abbas, Department of Thoracic Medicine and Surgery, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3401 N Broad St, C-501, Philadelphia, PA 19140.

References

- 1.Heller E Extramukose Kardioplastik beimchronischen Kardiospasmus mit Dilatation des Oesophagus. . Mitteilungen aus den Grenzgebieten der Medizin und Chirurgie. 1914;27:141. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heyrovsky H Casuistik und Therapie der idiopathischen Dilatation der Speiserohre: Oesophagogastroanastomose. Arch Klin Chir. 1913;100:703–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Payne WS. Heller’s contribution to the surgical treatment of achalasia of the esophagus. 1914. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989. December;48(6):876–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steichen FM, Ravitch MM. Ernst Heller, M.D., 1877–1964. N Y State J Med. 1965. October 1;65(19):2500–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wendel W Zur Chirurgie des Oesophagus. Arch Klin Chir. 1910;93:311–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grondahl N Cardiaplastik ved cardiospasmus. Nord Kirurgisk Forenings. 1916;11:236–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrett NR, Franklin RH. Concerning the unfavourable late results of certain operations performed in the treatment of cardiospasm. Br J Surg. 1949. October;37(146):194,202, illust. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ripley HR, Olsen AM, Kirklin JW. Esophagitis after esophagogastric anastomosis. Surgery. 1952. July;32(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisichella PM, Patti MG. A One Hundred Year Journey: The History of Surgery for Esophageal Achalasia In: Fisichella PM, Herbella FAM, Patti MG, editors. Achalasia: Diagnosis and Treatment. Switzerland.: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassotti G, Annese V. Review article: pharmacological options in achalasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999. November;13(11):1391–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traube M, Dubovik S, Lange RC, McCallum RW. The role of nifedipine therapy in achalasia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989. October;84(10):1259–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Wilcox CM, Schroeder PL, Birgisson S, Slaughter RL, et al. Botulinum toxin versus pneumatic dilatation in the treatment of achalasia: a randomised trial. Gut. 1999. February;44(2):231–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pellegrini C, Wetter LA, Patti M, Leichter R, Mussan G, Mori T, et al. Thoracoscopic esophagomyotomy. Initial experience with a new approach for the treatment of achalasia. Ann Surg. 1992. September;216(3):291,6; discussion 296–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimi S, Nathanson LK, Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic cardiomyotomy for achalasia. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1991. June;36(3):152–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patti MG, Pellegrini CA, Horgan S, Arcerito M, Omelanczuk P, Tamburini A, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for achalasia: an 8-year experience with 168 patients. Ann Surg. 1999. October;230(4):587,93; discussion 593–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyass S, Thoman D, Steiner JP, Phillips E. Current status of an antireflux procedure in laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Surg Endosc. 2003. April;17(4):554–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards WO, Torquati A, Holzman MD, Khaitan L, Byrne D, Lutfi R, et al. Heller myotomy versus Heller myotomy with Dor fundoplication for achalasia: a prospective randomized double-blind clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2004. September;240(3):405,12; discussion 412–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kummerow Broman K, Phillips SE, Faqih A, Kaiser J, Pierce RA, Poulose BK, et al. Heller myotomy versus Heller myotomy with Dor fundoplication for achalasia: long-term symptomatic follow-up of a prospective randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2018. April;32(4):1668–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kummerow Broman K, Phillips SE, Faqih A, Kaiser J, Pierce RA, Poulose BK, et al. Heller myotomy versus Heller myotomy with Dor fundoplication for achalasia: long-term symptomatic follow-up of a prospective randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2018. April;32(4):1668–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreollo NA, Earlam RJ. Heller’s myotomy for achalasia: is an added anti-reflux procedure necessary? Br J Surg. 1987. September;74(9):765–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rebecchi F, Giaccone C, Farinella E, Campaci R, Morino M. Randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Heller myotomy plus Dor fundoplication versus Nissen fundoplication for achalasia: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2008. December;248(6):1023–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumagai K, Kjellin A, Tsai JA, Thorell A, Granqvist S, Lundell L, et al. Toupet versus Dor as a procedure to prevent reflux after cardiomyotomy for achalasia: results of a randomised clinical trial. Int J Surg. 2014;12(7):673–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagedorn C, Jonson C, Lonroth H, Ruth M, Thune A, Lundell L. Efficacy of an anterior as compared with a posterior laparoscopic partial fundoplication: results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2003. August;238(2):189–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawlings A, Soper NJ, Oelschlager B, Swanstrom L, Matthews BD, Pellegrini C, et al. Laparoscopic Dor versus Toupet fundoplication following Heller myotomy for achalasia: results of a multicenter, prospective, randomized-controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2012. January;26(1):18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torres-Villalobos G, Coss-Adame E, Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Romero-Hernandez F, Blancas-Brena B, Torres-Landa S, et al. Dor Vs Toupet Fundoplication After Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy: Long-Term Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluated by High-Resolution Manometry. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018. January;22(1):13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiudelis M, Kubiliute E, Sakalys E, Jonaitis L, Mickevicius A, Endzinas Z. The choice of optimal antireflux procedure after laparoscopic cardiomyotomy: two decades of clinical experience in one center. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2017. September;12(3):238–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horgan S, Galvani C, Gorodner MV, Omelanczuck P, Elli F, Moser F, et al. Robotic-assisted Heller myotomy versus laparoscopic Heller myotomy for the treatment of esophageal achalasia: multicenter study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005. November;9(8):1020,9; discussion 1029–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huffmanm LC, Pandalai PK, Boulton BJ, James L, Starnes SL, Reed MF, et al. Robotic Heller myotomy: a safe operation with higher postoperative quality-of-life indices. Surgery. 2007. October;142(4):613,8; discussion 618–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeso S, Reza M, Mayol JA, Blasco JA, Guerra M, Andradas E, et al. Efficacy of the Da Vinci surgical system in abdominal surgery compared with that of laparoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2010. August;252(2):254–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaninotto G, Annese V, Costantini M, Del Genio A, Costantino M, Epifani M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of botulinum toxin versus laparoscopic heller myotomy for esophageal achalasia. Ann Surg. 2004. March;239(3):364–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stefanidis D, Richardson W, Farrell TM, Kohn GP, Augenstein V, Fanelli RD, et al. SAGES guidelines for the surgical treatment of esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc. 2012. Feb;26(2):296–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Paroutoglou G, Beltsis A, Zavos C, Papaziogas B, et al. Long-term results of pneumatic dilation for achalasia: a 15 years’ experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2005. September 28;11(36):5701–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inoue H, Minami H, Satodate H et al. First clinical experience of submucosal endoscopic myotomy for esophageal achalasia with no skin incision. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:AB122. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y, Sato Y, Kaga M, Suzuki M, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy. 2010. April;42(4):265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haito-Chavez Y, Inoue H, Beard KW, Draganov PV, Ujiki M, Rahden BHA, et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Adverse Events Associated With Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy in 1826 Patients: An International Multicenter Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017. August;112(8):1267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kane ED, Budhraja V, Desilets DJ, Romanelli JR. Myotomy length informed by high-resolution esophageal manometry (HREM) results in improved per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) outcomes for type III achalasia. Surg Endosc. 2019. March;33(3):886–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swanstrom LL, Kurian A, Dunst CM, Sharata A, Bhayani N, Rieder E. Long-term outcomes of an endoscopic myotomy for achalasia: the POEM procedure. Ann Surg. 2012. October;256(4):659–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Von Renteln D, Fuchs KH, Fockens P, Bauerfeind P, Vassiliou MC, Werner YB, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of achalasia: an international prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. 2013. August;145(2):309,11. e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Familiari P, Gigante G, Marchese M, Boskoski I, Tringali A, Perri V, et al. Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy for Esophageal Achalasia: Outcomes of the First 100 Patients With Short-term Follow-up. Ann Surg. 2016. January;263(1):82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werner YB, Costamagna G, Swanstrom LL, von Renteln D, Familiari P, Sharata AM, et al. Clinical response to peroral endoscopic myotomy in patients with idiopathic achalasia at a minimum follow-up of 2 years. Gut. 2016. June;65(6):899–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ngamruengphong S, Inoue H, Ujiki MB, Patel LY, Bapaye A, Desai PN, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy for Treatment of Achalasia After Failed Heller Myotomy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017. October;15(10):1531,1537. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ponds FA, Fockens P, Lei A, Neuhaus H, Beyna T, Kandler J, et al. Effect of Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy vs Pneumatic Dilation on Symptom Severity and Treatment Outcomes Among Treatment-Naive Patients With Achalasia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019. July 9;322(2):134–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng F, Li P, Wang Y, Ji M, Wu Y, Yu L, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy compared with pneumatic dilation for newly diagnosed achalasia. Surg Endosc. 2017. November;31(11):4665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumbhari V, Familiari P, Bjerregaard NC, Pioche M, Jones E, Ko WJ, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux after peroral endoscopic myotomy: a multicenter case-control study. Endoscopy. 2017. July;49(7):634–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schlottmann F, Luckett DJ, Fine J, Shaheen NJ, Patti MG. Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy Versus Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) for Achalasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2018. March;267(3):451–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johansson J, Hakansson HO, Mellblom L, Kempas A, Johansson KE, Granath F, et al. Prevalence of precancerous and other metaplasia in the distal oesophagus and gastrooesophageal junction. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005. August;40(8):893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, Sorensen HT, Funch-Jensen P. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011. October 13;365(15):1375–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The Risks and Benefits of Long-term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review and Best Practice Advice From the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017. March;152(4):706–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zoll B, Jehangir A, Malik Z, Edwards MA, Petrov RV, Parkman HP. Gastric Electric Stimulation for Refractory Gastroparesis. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2019. Jan;26(1):27–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richter JE, Kumar A, Lipka S, Miladinovic B, Velanovich V. Efficacy of Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication vs Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication or Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018. April;154(5):1298,1308. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hunter JG, Kahrilas PJ, Bell RC, Wilson EB, Trad KS, Dolan JP, et al. Efficacy of transoral fundoplication vs omeprazole for treatment of regurgitation in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015. February;148(2):324,333. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trad KS, Fox MA, Simoni G, Shughoury AB, Mavrelis PG, Raza M, et al. Transoral fundoplication offers durable symptom control for chronic GERD: 3-year report from the TEMPO randomized trial with a crossover arm. Surg Endosc. 2017. June;31(6):2498–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyberg A, Choi A, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Transoral incisional fundoplication for reflux after peroral endoscopic myotomy: a crucial addition to our arsenal. Endosc Int Open. 2018. May;6(5):E549–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mandovra P, Kalikar V, Patel A, Patankar RV. Redo Laparoscopic Heller’s Cardiomyotomy for Recurrent Achalasia: Is Laparoscopic Surgery Feasible? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018. March;28(3):298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vigneswaran Y, Yetasook AK, Zhao JC, Denham W, Linn JG, Ujiki MB. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM): feasible as reoperation following Heller myotomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014. June;18(6):1071–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tyberg A, Seewald S, Sharaiha RZ, Martinez G, Desai AP, Kumta NA, et al. A multicenter international registry of redo per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) after failed POEM. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017. June;85(6):1208–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernandez-Ananin S, Fernandez AF, Balague C, Sacoto D, Targarona EM. What to do when Heller’s myotomy fails? Pneumatic dilatation, laparoscopic remyotomy or peroral endoscopic myotomy: A systematic review. J Minim Access Surg. 2018. Jul-Sep;14(3):177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Griffiths EA, Devitt PG, Jamieson GG, Myers JC, Thompson SK. Laparoscopic stapled cardioplasty for end-stage achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013. May;17(5):997–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Orringer MB, Orringer JS. Esophagectomy: definitive treatment for esophageal neuromotor dysfunction. Ann Thorac Surg. 1982. September;34(3):237–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schuchert MJ, Luketich JD, Landreneau RJ, Kilic A, Wang Y, Alvelo-Rivera M, et al. Minimally invasive surgical treatment of sigmoidal esophagus in achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009. June;13(6):1029,35; discussion 1035–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dehn TC, Slater M, Trudgill NJ, Safranek PM, Booth MI. Laparoscopic stapled cardioplasty for failed treatment of achalasia. Br J Surg. 2012. September;99(9):1242–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu JW, Li QL, Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Zhang YQ, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for advanced achalasia with sigmoid-shaped esophagus: long-term outcomes from a prospective, single-center study. Surg Endosc. 2015. September;29(9):2841–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tustumi F, Bernardo WM, da Rocha JRM, Szachnowicz S, Seguro FC, Bianchi ET, et al. Esophageal achalasia: a risk factor for carcinoma. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2017. October 1;30(10):1 −8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inoue H, Ueno A, Shimamura Y, Manolakis A, Sharma A, Kono S, et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy and fundoplication: a novel NOTES procedure. Endoscopy. 2019. February;51(2):161–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodriguez L, Rodriguez P, Gomez B, Ayala JC, Oxenberg D, Perez-Castilla A, et al. Two-year results of intermittent electrical stimulation of the lower esophageal sphincter treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surgery. 2015. March;157(3):556–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rieder E, Paireder M, Kristo I, Schwameis K, Schoppmann SF. Electrical Stimulation of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter to Treat Gastroesophageal Reflux After POEM. Surg Innov. 2018. August;25(4):346–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Furuzawa-Carballeda J, Torres-Landa S, Valdovinos MA, Coss-Adame E, Martin Del Campo LA, Torres-Villalobos G. New insights into the pathophysiology of achalasia and implications for future treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2016. September 21;22(35):7892–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]