Abstract

Background

Indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies include follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and marginal zone lymphomas. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is a lymphoid malignancy similar to small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) in its leukaemic phase.

Indolent lymphoid malignancies including CLL are characterised by slow growth, a high initial response rate and a relapsing and progressive disease course. Advanced‐stage indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies are often incurable. If symptoms or progressive disease occur, chemotherapy plus rituximab is indicated. No chemotherapy regimen has been shown to improve overall survival compared to a different regimen.

Bendamustine is efficacious in the treatment of patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies. A number of randomised controlled trials have examined the effect of bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy regimens in these patients. Improved disease control with no survival benefit is shown.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of bendamustine therapy for patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies including CLL.

Search methods

We electronically searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 2), MEDLINE (1966 to May 2012), EMBASE (1974 to November 2011), LILACS (1982 to May 2012), databases of ongoing trials (accessed 30 April 2012) and relevant conference proceedings. We searched references of identified trials and contacted the first author of each included trial.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials that compared a bendamustine‐containing regimen to other chemotherapy with or without immunotherapy.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently appraised the quality of each trial and extracted data from included trials. We estimated and pooled hazard ratios (HR) and risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

We included five trials randomising 1343 adult patients in the systematic review. Allocation and blinding were unclear in three trials and adequate in two. Incomplete outcome data and selective reporting were adequate in all trials. Trials varied in the type of lymphoid malignancy, bendamustine regimen and the comparator regimen. In the three trials that included patients with follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma and other indolent lymphomas the comparator treatment was cyclophosphamide, a combination of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and prednisone, and fludarabine. Two trials included only patients with CLL and compared bendamustine to chlorambucil, and to fludarabine. We did not conduct a meta‐analysis due to the clinical heterogeneity among trials. Bendamustine had no statistically significant effect on the overall survival of patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies in any of the included trials (trials of moderate quality). Progression‐free survival was statistically significantly improved with bendamustine treatment compared to other chemotherapy in three of the four trials that reported on it. One trial demonstrated a non statistically significant improvement of PFS. The risk of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was similar when bendamustine was compared to CHOP and fludarabine, and higher when compared to chlorambucil. Compared to chlorambucil quality of life was unaffected by bendamustine treatment (one trial, no meta‐analysis).

Authors' conclusions

As none of the currently available chemotherapeutic protocols for induction therapy in indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies confer a survival benefit and due to the improved progression‐free survival in each of the included trials, and a similar rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events, bendamustine may be considered for the treatment of patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies. However, the unclear effect on survival and the higher rate of adverse events compared to chlorambucil in patients with CLL/SLL does not support the use of bendamustine for these patients.

The effect of bendamustine combined with rituximab should be evaluated in randomised clinical trials with more homogenous populations and outcomes for specific subgroups of patients by type of lymphoma should be reported. Any future trial should evaluate the effect of bendamustine on quality of life.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Antineoplastic Agents, Alkylating; Antineoplastic Agents, Alkylating/therapeutic use; Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols; Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols/administration & dosage; Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols/therapeutic use; Bendamustine Hydrochloride; Cyclophosphamide; Cyclophosphamide/administration & dosage; Cyclophosphamide/therapeutic use; Doxorubicin; Doxorubicin/administration & dosage; Leukemia, Lymphocytic, Chronic, B‐Cell; Leukemia, Lymphocytic, Chronic, B‐Cell/drug therapy; Leukemia, Lymphocytic, Chronic, B‐Cell/mortality; Lymphoma, B‐Cell; Lymphoma, B‐Cell/drug therapy; Lymphoma, B‐Cell/mortality; Lymphoma, Follicular; Lymphoma, Follicular/drug therapy; Lymphoma, Follicular/mortality; Lymphoma, Mantle‐Cell; Lymphoma, Mantle‐Cell/drug therapy; Lymphoma, Mantle‐Cell/mortality; Nitrogen Mustard Compounds; Nitrogen Mustard Compounds/therapeutic use; Prednisone; Prednisone/administration & dosage; Recurrence; Vincristine; Vincristine/administration & dosage; Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia; Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia/drug therapy; Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia/mortality

Plain language summary

Bendamustine for patients with slow‐growing lymphoma

Lymphoma is a cancer that originates from cells of the immune system in the lymph nodes, called lymphocytes. Slow‐growing (indolent) lymphoma is a group of lymphomas characterised by slow and continuous growth, a high initial response rate to treatment that target lymphoma cells (chemotherapy or rituximab), but a relapsing and progressive disease course. It includes follicular lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, mantle cell lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and marginal zone lymphoma. With current therapy people with advanced‐stage indolent lymphoma will experience relapse of their disease. Bendamustine is a type of chemotherapy that can be given to people with indolent lymphoma.

We conducted a review of the effect of bendamustine for people with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies. After searching for all relevant studies, we found five studies with 1343 people.

Our findings are summarised below:

In people with indolent B cell lymphoma:

‐ It is unclear whether bendamustine improves survival.

‐ Bendamustine may prevent or delay progression of lymphoma.

‐ Bendamustine may improve the response to treatment.

‐ Bendamustine probably causes more serious side effects than certain chemotherapeutic drugs (as the combination of adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone; or as fludarabine) and the same or less than other types of chemotherapy (chlorambucil).

‐ Only one study assessed quality of life and this study did not report different results for both treatment groups.

There were limitations to the review: the demographic characteristics of people that were involved in the studies, type of lymphoma, and the type of treatments that were given varied. Therefore it is difficult to draw clear conclusions.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Bendamustine compared with other therapy for B cell lymphoid malignancy | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancy Intervention: bendamustine Comparison: any treatment other than bendamustine (comparator intervention) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Assumed risk (control group) (events per 1000 patients) | Corresponding risk (bendamustine group) (events per 1000 patients) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Overall survival Median follow‐up: 35 to 44 months |

As for all‐cause mortality | As for all‐cause mortality | 481 patients (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Moderate quality due to serious imprecision: a wide confidence interval | |

|

All‐cause mortality Median follow‐up: 28 to 44 months |

326 per 1000 | 277 per 1000 | 1202 patients (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | Reasons and allocation of lost to follow‐up are not reported in 2 trials, unclear risk of bias | |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

CI: confidence interval NNT: number needed to treat

Background

Description of the condition

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification, published in 2001 and updated in 2008, attempts to group lymphomas by their corresponding normal cell (i.e. B cell, T cell and natural killer cell) using phenotypic, molecular and cytogenetic characteristics (Swerdlow 2008). The mature B cell lymphomas (also referred to as non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL)) can be divided by their clinical behaviour into aggressive (fast‐growing) and indolent (slow‐growing), the latter including up to 50% of NHL patients. Indolent lymphomas of mature B cell origin include follicular lymphoma (FL), small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and marginal zone lymphomas (MZL) (Harris 1994; Swerdlow 2008). Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is a lymphoid neoplasm that is similar to SLL in leukaemic phase (Rai 1975; Swerdlow 2008; Tsimberidou 2007). MCL has characteristics of aggressive as well indolent lymphoma.

The Ann Arbor staging system originally developed for Hodgkin's lymphoma provides the basis for anatomic staging of NHL. The Ann Arbor stage depends on both the extent of disease (as located with biopsy, computerised tomography (CT) scanning and positron emission tomography) and on systemic symptoms.

The International Prognostic Index (IPI) is a prognostic score with value in all of the NHL variants. Specific prognostic scores have been developed (follicular lymphoma IPI, FLIPI, and mantle cell lymphoma IPI, MIPI) (Hoster 2008; Hoster 2008b).

Indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies including CLL have many common characteristics, besides the common cell of origin (mature B cell). The watchful waiting strategy is acceptable in most indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies including CLL (Ardeshna 2003; CLL trialist 1999; Young 1988). Indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies, as the name indicates, are characterised by slow and continuous growth, a high initial response rate, but a relapsing and progressive disease course (Horning 1984). Advanced‐stage indolent NHL is often incurable. Chemotherapy regimens for the treatment of indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies include combinations of chlorambucil, mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and prednisone, and fludarabine‐based regimens. In recent years immunotherapy has been used to improve the clinical outcomes of patients with indolent NHL (Hallek 2010; Schulz 2007).

The course of indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies may be quite variable, depending on the histology as well as other variables. Patients with localised (early‐stage) lymphoma can be treated with radiotherapy and may be cured (MacManus 1996; Wilder 2001). For patients with advanced follicular lymphoma the average survival time is approximately 10 years. A number of studies that evaluated observation have compared treatment in patients with advanced stage indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies (Ardeshna 2003; Young 1988). These trials have brought the acceptance of the watchful waiting strategy and the development of indications for treatment. Despite major progress with the introduction of monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of indolent lymphoid neoplasms (Schulz 2007; Vidal 2009) the majority of patients cannot be cured with the currently available therapies.

The natural history of CLL/SLL is extremely variable and survival from initial diagnosis ranges from 2 to 20 years. The first staging system for CLL was developed by Rai (Rai 1975). It is based on the concept that in CLL there is a gradual and progressive increase in the burden of leukaemic lymphocytes. While median survival of patients with CLL Rai stage 0 (lymphocytosis alone) was 150 months, median survival of patients with Rai stage III or IV (anaemia or thrombocytopenia respectively) was 19 months. The Rai and the Binet staging system (which uses the number of involved lymphoid sites, anaemia and/or thrombocytopenia to define disease stage, Binet 1981) are simple yet accurate predictors of survival and are widely used by clinicians and researchers. Additional prognostic factors have been suggested, including immunophenotypic and cytogenetic abnormalities such as ZAP70 and CD38 or deletion 17p and mutation status (Hamblin 1999; Kienle 2010).

Description of the intervention

Most patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies present with advanced disease, i.e. stage III or IV. Asymptomatic patients can be observed (Ardeshna 2003; CLL trialist 1999; Young 1988). About a third of patients with CLL/SLL require repeated chemotherapy due to symptoms or advanced disease (Armitage 1998; Rai 1975). If treatment is required due to symptoms or progressive disease, immunotherapy‐based treatment (i.e. chemotherapy plus rituximab) is preferred as it improves response rate and prolongs progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (Hallek 2010; Schulz 2007). It is unknown which chemotherapy provides the best results combined with immunotherapy. Different chemotherapy regimens without rituximab have been compared including chlorambucil, combinations of mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, prednisone (MCP), cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone (COP), cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP), and fludarabine‐based regimens. None has been shown to improve time to progression‐free survival and overall survival (Glick 1981; Hagenbeek 2006; Klasa 2002; Nickenig 2006; Peterson 2003). Data from a large, multicentre prospective cohort study in the United States, the National LymphoCare Study (NLCS), found that 55% of patients with follicular lymphoma who require chemotherapy (regardless of disease stage) are treated with a CHOP protocol, 23% with a COP regimen and 15.5% using a fludarabine‐based regimen (Friedberg 2009).

In order to improve survival new first‐line treatments, as well as salvage regimens, are being sought.

Bendamustine, 5‐[Bis(2‐chloroethyl)amino]‐1‐methyl‐2‐benzimidazolebutyric acid hydrochloride, was developed and first studied in the German Democratic Republic more than 30 years ago by Ozegowski and Krebs (Ozegowski 1971). Its structure is characterised by a nitrogen mustard derivative linked to a benzimidazole nucleus, with a butanoic acid residue in position 2; this overall configuration is aimed at reducing the toxicity of the nitrogen mustard moiety. It therefore has structural similarities to both alkylating agents (nitrogen mustard derivative) and purine analogues (benzimidazole ring). Only partial cross‐resistance occurs between bendamustine and other alkylators (Strumberg 1996). Bendamustine can induce apoptosis of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cell lines (Chow 2001). Synergistic effects on apoptosis have been observed with combined rituximab and bendamustine in lymphoma cell lines in vitro, and in ex vivo cells from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (Rummel 2002).

Based on its structure and its in vitro activity its clinical activity has been assessed in the clinical setting to treat patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies including CLL.

How the intervention might work

A number of phase I/II trials support the efficacy of bendamustine for patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies as a single agent or in combination with other agents, including various chemotherapy protocols and anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) (Friedberg 2008; Heider 2001; Kahl 2010; Koenigsmann 2004; Robinson 2008b; Rummel 2005; Weide 2002; Weide 2004). Bendamustine has been combined with rituximab in patients with relapsed CLL (Fischer 2008; Weide 2004). The overall response rate was 77%, with a 15% complete response rate. It was well tolerated: grade 3/4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia occurred in 12% and 9% of all courses, respectively. Grade 3/4 infection‐related adverse events occurred in 5% of courses, with treatment‐related deaths in 4% of patients (Fischer 2008). Bendamustine is well tolerated even in heavily pre‐treated lymphoma patients, as monotherapy and in combination with other chemotherapy, its main adverse effects being leucopenia and thrombocytopenia (Fischer 2008; Heider 2001; Kahl 2010).

Bendamustine has been recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of CLL and rituximab‐refractory indolent B cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma.

Why it is important to do this review

A number of randomised controlled trials have examined the effect of bendamustine in patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies. Progression‐free survival was similar or prolonged with bendamustine compared to control and a survival benefit has not been shown.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy of bendamustine therapy for patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies including CLL.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials, irrespective of publication status and language.

Types of participants

Patients with histologically confirmed indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies, i.e. SLL/CLL, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma.

We included both patients receiving bendamustine as first‐line therapy and patients with relapsed or refractory disease receiving it as salvage therapy. Patients might have received high‐dose chemotherapy following first‐line or salvage therapy.

We included patients of any age.

Types of interventions

Investigational intervention:

Bendamustine as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy and immunotherapy

Comparison interventions:

Observation or steroids alone

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy in combination with immunotherapy (i.e. rituximab) or radio‐immunotherapy

We included trials in which bendamustine was combined with immunotherapy or radio‐immunotherapy only if bendamustine was compared to chemotherapy combined with the same immunotherapy or radio‐immunotherapy.

Chemotherapy included:·

Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, fludarabine, mitoxantrone, vincristine

Steroids could be combined with any chemotherapeutic regimen

Types of outcome measures

As defined in Cheson 2007 and Hallek 2008.

Primary outcomes

Overall survival (OS)

All cause mortality. This outcome was added post‐hoc to protocol due to the scarcity of OS data.

Secondary outcomes

Progression‐free survival (PFS)

Complete response (CR)

Overall response (partial and complete response)

Quality of life

Treatment‐related mortality

Adverse events requiring discontinuation of therapy

Grade 3/4 adverse events

Infection‐related adverse events

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 2, see Appendix 1);

MEDLINE (1966 to May 2012) (through PubMed, see Appendix 2);

EMBASE (1974 to November 2011), see Appendix 3);

LILACS (1982 to May 2012), see Appendix 4);

clinical trials in haematological malignancies (www.hematology‐studies.org).

We used the terms 'lymphoma' and similar OR 'chronic lymphocytic leukaemia' and similar with the term 'bendamustine' and similar.

We combined the search terms with the highly sensitive search strategy for identifying reports of randomised controlled trials (Robinson 2002) in the MEDLINE search.

Searching other resources

We searched the conference proceedings of the American Society of Hematology (1995 to 2011), conference proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting (1995 to 2011) and proceedings of the European Hematology Association (2002 to 2011) for relevant abstracts.

We searched databases of ongoing and unpublished trials (accessed 30 April 2012): http://www.controlled‐trials.com/, http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct, http://clinicaltrials.nci.nih.gov/.

We contacted the first or corresponding author of each included study and researchers active in the field for information regarding unpublished trials or complementary information on their own trial. One author (Dr. Merkle on behalf of Dr. Knauf) (Knauf 2009) replied and provided additional data. Co‐ordinators of two ongoing clinical trials responded. One clinical trial (Roche) is ongoing and analysis has not yet been performed. Axel Hinke responded on behalf of Prof. Niederle (Study chair) and provided trial data (Niederle 2012).

We checked the citations of included trials and major reviews for additional studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (LV) inspected the title and, when available, the abstract and applied the inclusion criteria. Where relevant articles were identified, two review authors (LV, AG) obtained and inspected the full article independently and applied the inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement between the two review authors, a third author (RG) independently applied the inclusion criteria. We documented our justification for excluding studies.

We included trials regardless of publication status, date of publication and language.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LV, AG) independently extracted the data from the included trials. In case of disagreement between the two review authors, a third author (RG) independently extracted the data. We discussed the data extraction, documented decisions and, where necessary, contacted the authors of the studies for clarification. We collected all data on an intention‐to‐treat basis, where possible.

We extracted, checked and recorded the following data:

-

Characteristics of trials

Publication status: published, published as abstract, unpublished

Year (defined as recruitment initiation year) and country or countries of study

Trial sponsor (academic, industrial)

Intention‐to‐treat analysis: performed, possible to extract, efficacy analysis

Design (method of allocation generation and concealment, blinding)

Unit of allocation (patient, episodes, cluster)

Duration of study follow‐up

Response definition, event definitions

Case definitions used (inclusion and exclusion criteria)

Assessment of mortality (primary outcome, secondary outcome, safety)

-

Characteristics of patients

Number of participants in each group

Age (mean and standard deviation)

Type of disease (SLL/CLL, FL, MCL, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, MZL)

Disease status (untreated, previously treated)

Number of patients with performance status ≤ 2, > 2

Number of patients with stage III/IV disease (according to Ann Arbor)

Number of patients with bulky disease

Number of patients with elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels

-

Characteristics of interventions

Treatment of control group (regimen, dose, number of treatment days, length of cycle and planned total duration of therapy)

-

Experimental intervention

Dose, number of treatment days, length of cycle and planned total duration of therapy

Regimen (monotherapy, type of combination therapy)

-

Characteristics of outcome measures (extracted for each group and total events)

-

Overall survival

Number of deaths at 12, 36, 60 months, end of follow‐up

Number of patients available for follow‐up at the time of evaluation of survival risk

Hazard ratio (HR) of OS and its standard error (SE), confidence interval (CI) or P value

KM curve (yes/no)

HR of EFS and its SE, CI or P value

HR of PFS and its SE, CI or P value

Number of patients who achieved complete response (CR) at end of treatment

Number of patients who achieved partial response (PR) at end of treatment

Quality of life (scale and score)

Adverse events (any, grade 3 to 4, requiring discontinuation of treatment, infection‐related)

Number of patients excluded from outcome assessment after randomisation and the reasons for their exclusion

-

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LV, AG) independently assessed the trials for methodological quality. We described and assessed allocation concealment, sequence generation, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting individually and according to The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing bias (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion. If disagreement persisted, a third review author (RG) extracted the data independently. We discussed the data extraction, document disagreements and their resolution and, where necessary, contacted the authors of the studies for clarification. If this was unsuccessful, we reported disagreements.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to estimate risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous data and hazard ratios (HR) for time to event outcomes. We planned to estimate standardised mean difference (SMD) for quality of life assessment.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

We did not expect trials with a cross‐over design, as the effect of the chemotherapy in the first period is assumed to continue through the second period.

Multiple observations at different time points for the same outcome

For time to event meta‐analysis we used data at the longest follow‐up.

For dichotomous data we analysed outcome data at 12 and 60 months separately. We analysed adverse events at the end of chemotherapy, up to 12 months and, if data were available, at 60 months. We analysed response rates only at the end of chemotherapy, up to 12 months.

Events that may recur

Adverse events may occur more than once in the same individual, mainly during different treatment cycles. We extracted the number of patients in each arm and the number of patients who experienced at least one event. We counted each patient once even if repeated events occurred and analysed the data as dichotomous data.

Dealing with missing data

If possible, we imputed missing data for patients who were lost to follow‐up after randomisation (dichotomous data) assuming poor outcome (worse case scenario) for missing individuals.

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome excluding trials in which more than 20% of participants were lost to follow‐up.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity (the degree of difference between the results of different trials) using the Chi2 test of heterogeneity and the I2 statistic of inconsistency (Deeks 2011; Higgins 2003). We defined a statistically significant heterogeneity as P value less than 0.1 or an I2 statistic greater than 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

If at least 10 trials were included we would have inspected the funnel plot of the treatment effect against the precision of trials (plots of the log of the risk ratio for efficacy against the standard error) in order to estimate potential asymmetry that may indicate selection bias (the selective publication of trials with positive findings) or methodological flaws in the small studies (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Due to clinical heterogeneity no meta‐analysis was done.

If the HR and its SE (or CI) were not reported, we estimated ‘O – E’ and ‘V’ statistics indirectly using methods described by Parmar 1998.

We planned to pool log HR for time to event outcomes using an inverse variance method. A HR less than 1.0 is in favour of bendamustine treatment. We planned to estimate risk ratios (RR) and their CI for dichotomous data using the Mantel‐Haenszel method. For response rate a RR more than 1.0 is in favour of bendamustine treatment. For analysis of adverse events a RR less than 1.0 is in favour of bendamustine treatment. We planned to use a fixed‐effect model and to repeat the primary analysis using a random‐effects model (DerSimonian and Laird method) in a sensitivity analysis (Der Simonian 1997). We planned to estimate SMD for continuous data (quality of life scales) using the inverse variance method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to explore potential sources of heterogeneity and potentially important clinical characteristics through stratifying the primary outcome by the patient subgroups given below:

Age of patients (children, adults)

Type of lymphoma (SLL/CLL, FL, MCL, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, MZL)

Treatment line (first‐line, salvage treatment)

-

Type of treatment protocol

With or without rituximab

Bendamustine alone or in combination with other chemoimmunotherapy

-

Comparator treatment

No treatment or steroids

Chemoimmunotherapy

Alkylating agents based therapy

Purine analogues based therapy

We planned to formally assess differences between subgroups using the Chi2 test for difference between subgroups (Deeks 2001).

We did not perform analysis of survival in children as no children were included in the trials. Overall survival data were not reported according to the type of lymphoma, thus we could not perform such a subgroup analysis. Due to the small number of included trials we did not analyse overall survival by the treatment line, or by the type of treatment protocol.

Bendamustine was not compared to placebo, no treatment or steroids in any of the included trials. Therefore we did not carry out analysis of bendamustine with these comparators.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome using the method of allocation concealment (Schulz 1995); blinding (patients, caregivers and assessors); allocation generation; incomplete outcome data (adequately, inadequately addressed) (Higgins 2011), the type of publication (full paper, abstract, unpublished); and the size of trials.

Due to the small number of included trials we did not analyse overall survival by allocation concealment, blinding, allocation generation, incomplete outcome data, the type of publication and the size of trials.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We screened 339 titles and abstracts. Twenty‐six of them were relevant and we retrieved them for full details. We excluded 14 studies. An additional six ongoing trials were identified. Of them one provided us with the unpublished results (Niederle 2012). Five trials (13 publications) fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Herold 2006; Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010) (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Two trials were published as abstracts (Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010) and two as full text (Herold 2006; Knauf 2009). The report of one trial was accepted for publication (Niederle 2012). In these trials 1343 adult patients were randomised between the years 1994 and 2006. Three trials did not analyse all randomised patients (for details see Characteristics of included studies); 49 patients were not included in meta‐analyses, thus 1294 were evaluated. The median follow‐up ranged from 28 to 44 months.

Type of patients

All five eligible trials included adult patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies requiring chemotherapy. Three trials (Herold 2006; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010) included patients with follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and other indolent lymphomas. The percentage of patients with follicular lymphoma ranged from 40% to 52% and the percentage of patients with mantle cell lymphoma was about 20%. Two trials included only patients with CLL (Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012).

Three trials (Herold 2006; Knauf 2009; Rummel 2009) included previously untreated patients and two trials included previously treated patients (Niederle 2012; Rummel 2010).

A common inclusion criterion was good performance status (≤ 2 by Eastern Co‐operative Oncology Group (ECOG) or World Health Organization (WHO)). Common exclusion criteria included with renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction and active infection. Children were not included in any of the trials.

Chemotherapy of comparator group

Bendamustine was compared to an alkylating agent‐containing protocol in three trials (Herold 2006; Knauf 2009; Rummel 2009). Bendamustine was compared to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) (Rummel 2009), to cyclophosphamide (as part of the COP regimen) (Herold 2006) and to chlorambucil (Knauf 2009). Bendamustine was compared to a purine analogue (fludarabine) in two trials (Niederle 2012; Rummel 2010). The different comparators may be responsible for the statistical heterogeneity in secondary outcomes.

Bendamustine was not compared to placebo, no treatment or steroids in any of the included trials.

Chemotherapy protocol in the bendamustine group

The total dosage of bendamustine ranged from 180 mg/m2 to 300 mg/m2 body surface area (BSA), either divided into two days of treatment (90 to 100 mg/m2 BSA administered daily) and repeated every 28 days (Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010) or given over five days (60 mg/m2 BSA each day) and repeated every 21 days (Herold 2006).

In three trials (Niederle 2012; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010) rituximab was added to both treatment groups. In one trial (Herold 2006) vincristine and prednisone were added to the two allocated treatment groups (bendamustine versus cyclophosphamide).

Excluded studies

Fourtheen publications were not randomised controlled trials and were excluded (Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2: 'Risk of bias' summary.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Two trials were of high quality (Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012). We judged the quality of the other three trials as unclear as most of the domains of methodological quality are not reported (Herold 2006; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010).

Allocation

Allocation was adequately concealed in two trials (Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012) and was not reported in three trials (Herold 2006; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010). Sequence was adequately generated in two trials (Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012) and the method of random sequence generation was not reported in three trials (Herold 2006; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010).

We judged the quality of these trials as unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Patients and caregivers were not blinded to the allocated treatment in all the included trials. Outcome assessors were blinded to allocated treatment group in one trial (Knauf 2009).

We judged the quality of these trials as unclear risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

All randomised patients were included in the primary analysis of one trial (Knauf 2009). In three trials 7%, 5% and 1% (Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010; Herold 2006, respectively) of randomised patients were not analysed. Two trials reported reasons for drop‐outs but did not report the number of excluded in each group (Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010). Reasons for exclusions were specified in two reports (Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010), the allocation of patients excluded after randomisation was not reported in three (Herold 2006; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010). The number of randomised patients is unclear in Niederle 2012.

We judged the quality of these trials as low risk of bias.

Selective reporting

Four trials (Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012, Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010) addressed the outcomes specified in their protocol. The protocol of one trial (Herold 2006) was not available.

We judged the quality of these trials as low risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Overall survival (or mortality) was a secondary outcome in all the included trials.

Four trials were supported by funding from pharmaceutical companies (Herold 2006; Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012; Rummel 2009).

As mentioned above two trials were reported as abstracts (Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010).

We judged the quality of these trials as unclear risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We amended the protocol and did not pool results due to the high clinical heterogeneity as well as statistical heterogeneity of the patients in terms of disease (non‐Hodgkin’s lymphoma, CLL) and disease status (untreated, previously treated), interventions (different bendamustine‐containing protocols) and the various comparator protocols.

Overall survival

Three trials provided data on overall survival (Figure 3). All three showed a non‐statistically significant improvement in survival in the bendamustine group as indirectly estimated (Parmar 1998): Herold 2006: HR 0.93 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.44), Knauf 2009: HR 0.69 (95% CI 0.43 to 1.11), Niederle 2012: HR 0.82 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.42). Two trials (Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010) did not provide any data on overall survival.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, outcome: 1.1 Overall survival.

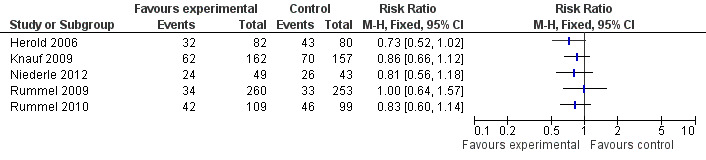

Five trials reported on all‐cause mortality (survival as dichotomous data). Although not preplanned, due to the scarcity of reported data and the importance of mortality outcome, we reported mortality as a dichotomous data and estimated the RR of death in each of the trials (Figure 4). Four trials showed a non‐significant improvement in all cause mortality in the bendamustine group and one trial showed no difference between groups (Rummel 2009).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, outcome: 1.2 All‐cause mortality.

Survival analysis in subgroups of patients

No children were included in any of the trials.

Data were not reported according to the type of lymphoma (SLL/CLL, FL, MCL, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, MZL), thus we could not perform a subgroup analysis according to the type of lymphoproliferative malignancy. Two trials included only patients with SLL/CLL (Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012) (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 3 All‐cause mortality by type lymphoid malignancy (fixed‐effect).

Moreover, due to the small number of included trials we did not analyse overall survival by the treatment line (Analysis 1.4), by type of comparator (Analysis 1.5), or by the type of investigational treatment protocol.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 4 All‐cause mortality by treatment line (fixed‐effect).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 5 All‐cause mortality by type of comparator (fixed‐effect).

We also present the results by the addition of rituximab to chemotherapy regimen in both allocated groups (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 7 Progression‐free survival.

Bendamustine was not compared to placebo, no treatment or steroids in any of the included trials. Therefore we did not carry out analysis of bendamustine with these comparators.

Progression‐free survival (PFS)

(See Figure 5).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, outcome: 1.7 Progression‐free survival.

Three of the four trials (1132 patients) that reported on PFS of patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies demonstrated an improved PFS with bendamustine compared to control (Knauf 2009; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010). One trial (Niederle 2012) demonstrated a non statistically significant improvement of PFS with bendamustine. No meta‐analysis was done. The estimated hazard ratios (HR) of disease progression or death were HR 0.28, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.42 (Knauf 2009, 319 patients); HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.64 (Niederle 2012, 92 patients); HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.77 (Rummel 2009, 513 patients); HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.71 (Rummel 2010, 208 patients).

Complete and overall response

Four trials reported on CR rates (Herold 2006; Knauf 2009; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010). We did not pool the results of complete and overall response rate due to high statistical heterogeneity (I2 of heterogeneity = 88% and 97%, respectively).

Bendamustine had no statistically significantly effect on CR rate as compared to cyclophosphamide (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.00, Herold 2006; RR more than 1 is in favour of bendamustine) and increased the RR of CR rate in three trials: compared to chlorambucil (RR 16.15, 95% CI 5.14 to 50.72, Knauf 2009); compared to CHOP (RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.64, Rummel 2009); compared to fludarabine (RR 2.38, 95% CI 1.44 to 3.96, Rummel 2010). Overall response rate was improved with bendamustine when compared to chlorambucil (RR 2.22, 95% CI 1.72 to 2.88, Knauf 2009) and fludarabine (RR 1.59, 95% CI 1.29 to 1.95, Rummel 2010), and was not affected compared to cyclophosphamide (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.05, Herold 2006) and CHOP (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.05, Rummel 2009). The high chance of heterogeneity makes these results difficult to interpret and may be explained by the intensity of the comparator chemotherapy.

Quality of life

The effect of bendamustine on quality of life was reported in one trial in which it was compared with chlorambucil (Knauf 2009). After completion of the study treatment no differences were demonstrated with respect to physical, social, emotional and cognitive functioning, and self assessment of global health status.

Adverse events

Treatment‐related mortality was reported in one trial (Herold 2006) in two patients of 82 treated with bendamustine and none of 80 patients in the comparator treatment group.

Adverse events requiring discontinuation of therapy were reported in one trial (Knauf 2009). Eighteen patients (11%) discontinued bendamustine therapy and five (3%) discontinued chlorambucil (P = 0.005).

Data regarding grade 3 to 4 adverse events were reported in three trials (Knauf 2009; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010). Due to the high statistical heterogeneity we did not pool the results of the three trials. Heterogeneity could be explained by the different comparator chemotherapy: while the risk of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was increased when bendamustine was compared to chlorambucil in patients with CLL (Knauf 2009), it was similar when it was compared to fludarabine in patients with indolent B cell lymphomas (Rummel 2010) and decreased compared to CHOP (Rummel 2009). Excluding the trial that compared bendamustine to chlorambucil (Knauf 2009) the pooled RR of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was statistically significantly higher with CHOP or fludarabine compared to bendamustine (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.89, I2 of heterogeneity = 0, fixed‐effect model).

Two trials reported infection‐related adverse events (Knauf 2009; Rummel 2009). In one trial (Knauf 2009) the rate of grade 3 or 4 infection was higher (8%, 13 of 161 patients) in the bendamustine group compared to chlorambucil (3%, 5 of 151 patients). In another trial that rate was decreased with bendamustine therapy (95 of 260 patients) compared to CHOP (121 of 253 patients) (Rummel 2009).

Discussion

Summary of main results

The previous reported evidence of bendamustine efficacy in the treatment of patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies including CLL is mainly based of non‐comparative reports, which were supportive of bendamustine therapy for patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies (Friedberg 2008; Heider 2001; Kahl 2010; Koenigsmann 2004; Robinson 2008b; Rummel 2005; Weide 2002; Weide 2004). This systematic review summarises the current data from randomised controlled trials. No meta‐analysis was done.

Bendamustine had no statistically significant effect on the overall survival of patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies in any of the included trials. Progression‐free survival (PFS) was statistically significantly improved with bendamustine treatment in each of the trials that reported it. No difference in the risk of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was shown with the bendamustine‐containing protocol. When bendamustine was compared to chlorambucil, quality of life was unaffected by the allocated treatment.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Due to the clinical heterogeneity and the small number of trials and patients, it is impossible to draw clear conclusions based on the results.

Trials were diverse in the type of included patients: the type of lymphoma, the treatment line, the type of bendamustine‐containing protocol and the type of comparator regimen. No reports on subgroups of patients according to type of lymphoma were available in the included trials. The clinical heterogeneity and lack of data might prevent us from recognising a subgroup of patients that may gain an overall survival benefit with bendamustine.

PFS was consistently better with bendamustine. Although one may argue that an improvement in quality of life may be translated into fewer lymphoma‐related symptoms and a longer time to the next treatment, this was not tested in the included trials. The clinical relevance of the improved PFS is unclear because patient‐important outcomes such as quality of life were evaluated in only one trial (Knauf 2009).

In two of the included trials (Herold 2006; Knauf 2009) induction treatment did not contain rituximab which has been shown to have an important role in the treatment of patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies including CLL/SLL.

Quality of the evidence

Five trials were included in the review (Herold 2006; Knauf 2009; Niederle 2012; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010). Three of them did not report the methods of randomisation generation and allocation concealment (Herold 2006; Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010). In none of the trials were the patients and caregivers blinded to allocated treatment. In one trial outcome assessors were blinded to allocated treatment (Knauf 2009), but these data were not reported in the other four trials. In two trials incomplete data were not adequately reported (Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010). Some of the gaps in reporting measures of quality of trials and mortality data might be because two trials were reported as abstracts (Rummel 2009; Rummel 2010), and one as personal communication (Niederle 2012).

Despite clinical heterogeneity there is no statistical heterogeneity in the analysis of overall survival.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Current evidence does not support the use of any specific chemotherapy over the other in the treatment of patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies.

Fludarabine was shown to improve the response rate of patients with CLL who require therapy and is the standard of care for fit patients (Catovsky 2007). Systematic reviews of the effect of purine analogues on clinical outcomes in patients with CLL did not show a survival benefit with fludarabine (Richards 2012; Steurer 2006; Zhu 2004). Other chemotherapy options in CLL are chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide (alone or in combination with purine analogues), COP, CHOP and alemtuzumab (Kimby 2001). None of these options were found to be superior over the other in terms of survival. A systematic review examining the effect of chlorambucil on disease control and overall survival is now in progress (Vidal 2011).

The available chemotherapy regimens for indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies include CHOP, COP, fludarabine‐containing regimens, MCP and chlorambucil (Friedberg 2009). None of these regimens was shown to improve survival. A systematic review of anthracycline‐containing regimens for the treatment of follicular lymphoma is now in progress. A preliminary report of the meta‐analysis showed a progression‐free survival benefit but no overall survival benefit (Itchaki 2010).

The lack of clear superiority of any of the chemotherapeutic regimens and the results of the included five randomised controlled trials make bendamustine an optional treatment for patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Due to the improved progression‐free survival in the primary trials, similar survival and a similar or lower rate of grade 3 or 4 adverse events compared to CHOP and to fludarabine, bendamustine may be considered in the treatment of patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies. For patients with refractory or relapsed CLL bendamustine may be considered for patients eligible for fludarabine treatment. For patients with CLL who are candidates only for chlorambucil, treatment with bendamustine is associated with a higher rate of adverse events and no survival benefit and is therefore not recommended.

Implications for research.

The effect of bendamustine combined with rituximab should be evaluated in randomised clinical trials with a more homogenous population and the outcomes of subgroups of patients by the type of lymphoma should be reported. Future trials should put an emphasis on the effect of bendamustine on quality of life. Quality of life is one of the most important outcomes for patients with indolent B cell lymphoid malignancies and as such this should be evaluated and reported.

Bendamustine should be compared with a fludarabine‐containing regimen as first‐line treatment, with rituximab for the treatment of patients with small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukaemia .

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Nicole Skoetz, Dr. Kathrin Bauer and Andrea Will of the Cochrane Haematological Malignancies Group (CHMG) Editorial Base, Ina Monsef for her help in constructing the search strategy and running the search, Dr. Olaf Weingart and Dr. Sven Trelle (Editors), as well as Céline Fournier (Consumer Editor) for their comments and review improvements.

We would like to thank Drs. Knauf and Merkle (Knauf 2009), and Drs. Hinke and Ibach (Niederle 2012) for their help and providing complementary data.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

| ID | Search |

| #1 | bendamustin* |

| #2 | ribomustin* |

| #3 | treand* |

| #4 | levact* |

| #5 | SDX |

| #6 | cytostasan* |

| #7 | Zimet* |

| #8 | Imet* |

| #9 | (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8) |

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

| # | Searches |

| 1 | bendamustin$.tw,kf,ot. |

| 2 | ribomustin$.tw,kf,ot. |

| 3 | treand$.tw,kf,ot. |

| 4 | levact$.tw,kf,ot. |

| 5 | "SDX‐105".tw,kf,ot. |

| 6 | cytostasan$.tw,kf,ot. |

| 7 | zimet$.tw,kf,ot,nm. |

| 8 | imet$.tw,kf,ot,nm. |

| 9 | or/1‐8 |

| 10 | randomized controlled trial.pt. |

| 11 | controlled clinical trial.pt. |

| 12 | randomized.ab. |

| 13 | placebo.ab. |

| 14 | drug therapy.fs. |

| 15 | randomly.ab. |

| 16 | trial.ab. |

| 17 | groups.ab. |

| 18 | or/10‐17 |

| 19 | humans.sh. |

| 20 | 18 and 19 |

| 21 | 9 and 20 |

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

| # | Searches |

| 1 | Bendamustine/ |

| 2 | bendamustin$.tw. |

| 3 | ribomustin$.tw. |

| 4 | treand$.tw. |

| 5 | levact$.tw. |

| 6 | "SDX‐105".tw. |

| 7 | cytostasan$.tw. |

| 8 | zimet$.tw. |

| 9 | imet$.tw. |

| 10 | Or/1‐9 |

| 11 | (random$ or placebo$).ti,ab. |

| 12 | ((single$ or double$ or triple$ or treble$) and (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. |

| 13 | Controlled clinical trial$.ti,ab. |

| 14 | RETRACTED ARTICLE/ |

| 15 | Or/11‐14 |

| 16 | (animal$ not human$).sh,hw. |

| 17 | 15 not 16 |

| 18 | 10 and 17 |

Appendix 4. LILACS search strategy

The following terms were searched:

bendamustine

bendamustin

cytostasan

Treanda

Ribomustin

Zimet 3393

IMET 3393

Appendix 5. Database of clinical trials in haematological malignancies search strategy

Bendamustine

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 3 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 All‐cause mortality | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 All‐cause mortality by type lymphoid malignancy (fixed‐effect) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Lymphoma | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 CLL (excluding lymphoma) | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 All‐cause mortality by treatment line (fixed‐effect) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 First‐line treatment | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 Second‐line treatment and more | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 All‐cause mortality by type of comparator (fixed‐effect) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Alkylating agents based comparator | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Purine analogues based comparator | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 All‐cause mortality with or without rituximab (fixed‐effect) | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Chemotherapy‐only regimens | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.2 Rituximab chemotherapy regimens | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Progression‐free survival | 4 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Complete response | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9 Overall response rate (complete and partial remission) | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10 Grade 3 to 4 adverse events | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 11 Grade 3 to 4 adverse events without CLL patients | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 2 All‐cause mortality.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 6 All‐cause mortality with or without rituximab (fixed‐effect).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 8 Complete response.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 9 Overall response rate (complete and partial remission).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 10 Grade 3 to 4 adverse events.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bendamustine compared to other chemotherapy, Outcome 11 Grade 3 to 4 adverse events without CLL patients.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Herold 2006.

| Methods | Allocation generation: unclear Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: no ITT: no Number of dropouts: 2/164 Median follow‐up: 44 months | |

| Participants | 164 randomised, 162 evaluable, adult patients

Type of lymphoma: follicular, mantle cell, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma

Stage: III/IV Previous treatment: no Mean age: 58 years WHO Performance status: < 2 |

|

| Interventions | Investigational intervention: Bendamustine 60 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5, vincristine 2 mg on day 1 and prednisone 100 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5; every 3 weeks, for 8 cycles Comparator intervention: Cyclophosphamide 400 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5, vincristine 2 mg on day 1 and prednisone 100 mg/m2 on days 1 to 5; every 3 weeks, for 8 cycles |

|

| Outcomes | Survival time was defined as time from the start of therapy until death Time to progression was defined as the time from the start of therapy until progression or disease‐related death, and was reported in responding patients Time to treatment failure was defined as the time from the start of therapy until treatment failure (objective progression, change of randomised therapy, intolerable toxicity or death for any reason). Rates of treatment failure in each group are described, but time to treatment failure is reported only in responding patients CR, PR Adverse events |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 2 patients (1%) were not evaluable and not included in the analysis. Reasons and allocation were not specified |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The trial's protocol was not available to evaluate selective reporting Time to progression and time to treatment failure were reported only in responding patients |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Funded by Ribosepharm GmbH, Clinical Research, Munich |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Participants and personnel were not blinded to allocated treatment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

Knauf 2009.

| Methods | Allocation generation: adequate Allocation concealment: adequate Blinding: no ITT: yes Number of dropouts: 0 (all patients were included in the analysis, 7 patients did not start allocated therapy) Median follow‐up: 35 months (range, 1 to 68) | |

| Participants | 319 randomised adult patients

Type of lymphoma: CLL/SLL

Stage: Binet B/C Previous treatment: no Mean age: 63 years, median 63 and 66 years WHO performance status: 303/311 patients < 2, 8/311 patients = 2 |

|

| Interventions | Investigational intervention: IV bendamustine 100 mg/m2 on days 1 to 2; every 4 weeks Comparator intervention: Oral chlorambucil 0.8 mg/kg on days 1 and 15; every 4 weeks |

|

| Outcomes | Primary endpoints: Overall response rate: CR or PR Progression‐free survival Secondary endpoints: Time to progression Duration of remission Overall survival Adverse events, including infection rate |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | The randomisation list (random number table) was generated by an independent statistical institute. Patients were randomised in a 1:1 ratio consecutively in the order of the CRO’s notification of study entry performing prospective stratification by centre and Binet stage (Binet B or C). For the generation of blocks and stratification by centre and Binet stage a validated software program RanCode (IDV‐Gauting, Germany) was used |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All patients were included in the analysis of overall survival and progression‐free survival. 7 patients were not treated (1 allocated to bendamustine, 6 to chlorambucil) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Analyses were done as stated in protocol |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Supported by grants from Ribosepharm GmbH, Germany and Mundipharma International, United Kingdom |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Participants and personnel were not blinded to allocated treatment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Final assessment of best response was performed in a blinded fashion by an Independent Committee for Response Assessment (ICRA) and classified as ... based on the National Cancer Institute Working Group criteria" |

Niederle 2012.

| Methods | Allocation generation: computer generated Allocation concealment: central Blinding: no Number of dropouts: 4 not eligible/96 Median follow‐up: 36 months | |

| Participants | 92 randomised adult patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia requiring treatment after 1 previous systemic regimen

Type of lymphoma: CLL/SLL

Stage: Binet B/C Previous treatment: 1 line (refractory or relapse) Mean age: 68 years WHO Performance status: < 3 |

|

| Interventions | Investigational: bendamustine 100 mg/m2 iv, day 1 + 2, q4w Comparator: fludarabine 25 mg/m2 iv, days 1 to 5, q4w |

|

| Outcomes | (Non‐inferior) progression‐free survival Overall survival |

|

| Notes | Unpublished data provided by the investigators as individual patient data | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated randomisation lists, created by a block randomisation method with variable block size |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 4 randomised patients were ineligible and were not included in the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Analyses were done as stated in protocol |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Responsible party and sponsor: WiSP Wissenschaftlicher Service Pharma GmbH |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding, open label |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | No blinding |

Rummel 2009.

| Methods | Allocation generation: not reported Allocation concealment: not reported Blinding: no ITT: no Number of dropouts: 36/549 Median follow‐up: 28 months | |

| Participants | 549 randomised, 513 evaluable, adult patients

Type of lymphoma: follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, other indolent lymphoma

Stage: 96% of patients stage III/IV Previous treatment: no Mean age: 64 years (range 31 to 83 years) |

|

| Interventions | Investigational intervention: Bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 1 to 2, and rituximab 375 mg/m2 on day 1; every 4 weeks, up to 6 cycles Comparator intervention: Standard CHOP and rituximab 375 mg/m2 on day 1; every 3 weeks, up to 6 cycles |

|

| Outcomes | Progression‐free survival Overall survival Event‐free survival. An event was defined by a response less than a partial response, disease progression, relapse or death from any cause Time to next treatment Adverse events |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | "Of the 549 randomized patients 36 patients were not evaluable: 10 did not receive any study medication, 9 due to withdrawal of consent, 13 due to incorrect diagnosis, and 4 for other reasons." Allocation of non‐evaluable patients is not reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Analyses were done as stated in protocol |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Research funding by Roche Pharma AG Published as an abstract |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Participants and personnel were not blinded to allocated treatment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

Rummel 2010.

| Methods | Allocation generation: not reported Allocation concealment: not reported Blinding: no ITT: no Number of dropouts: 11/219 Median follow‐up: 33 months | |

| Participants | 219 randomised, 208 evaluable, adult patients

Type of lymphoma: follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, other indolent lymphoma

Stage: 93% of patients allocated to bendamustine and 86% allocated to fludarabine stage III/IV Previous treatment: yes Mean age: 68 years (range 38 to 87 years) |

|

| Interventions | Investigational intervention: Bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 1 to 2, and rituximab 375 mg/m2 on day 1; every 4 weeks, up to 6 cycles Comparator intervention: Fludarabine 25 mg/m2 on days 1 to 3 and rituximab 375 mg/m2 on day 1; every 4 weeks, up to 6 cycles |

|

| Outcomes | Progression‐free survival Overall survival |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | "219 patients ... were randomized ...11 patients were not evaluable due to protocol violations, and were not followed further" Allocation of non‐evaluable patients is not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Analyses were done as stated in protocol |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Published as an abstract |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Participants and personnel were not blinded to allocated treatment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukaemia CR: complete response ITT: intention‐to‐treat iv: intravenous PR: partial response SLL: small lymphocytic lymphoma

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Catovsky 2011 | No allocation to bendamustine treatment |

| Cheson 2010 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| D'Elia 2010 | Not a randomised controlled trial (a case report of bendamustine for a patient with Hodgkin's lymphoma) |

| Ferrajoli 2005 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| Friedberg 2008 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| Hesse 1972 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| Hesse 1972b | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| Kath 2001 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| Moosmann 2010 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| No authors listed | A review |

| No authors listed B | A review |

| Robinson 2008 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| Rummel 2011 | A review |

| Treon 2011 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Cephalon.

| Trial name or title | Study of bendamustine hydrochloride and rituximab (BR) compared with R‐CVP or R‐CHOP in the first‐line treatment of patients with advanced indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) ‐ referred to as the BRIGHT study |

| Methods | The primary objective of the study is to compare the complete response (CR) rate of bendamustine and rituximab (BR) with that of standard treatment regimens of either rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (R‐CVP) or rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R‐CHOP) in patients with advanced, indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). An open‐label, randomised, parallel group study of bendamustine hydrochloride and rituximab (BR) compared with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (R‐CVP) or rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R‐CHOP) in the first‐line treatment of patients with advanced, indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) |

| Participants | Previously untreated patients with advanced indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) |

| Interventions | Bendamustine and rituximab

versus R‐CVP or R‐CHOP |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measures:

Complete response (CR) rate at end of treatment of bendamustine and rituximab (BR) with either R‐CVP or R‐CHOP in the treatment of patients with advanced indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma or mantle cell lymphoma Secondary outcome measures: Safety and tolerability of BR and R‐CVP, or R‐CHOP Overall response rate (ORR) = complete remission (CR) and partial remission (PR) Progression‐free survival Quality of life, as determined by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 30‐item core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ‐C30) Median durations of responses |

| Starting date | April 2009 |

| Contact information | Cephalon |

| Notes | NCT00877006 |

Chen.

| Trial name or title | Bendamustine hydrochloride injection for initial treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised Endpoint classification: safety/efficacy study Intervention model: parallel assignment Masking: open label Primary purpose: treatment |

| Participants | Untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients |

| Interventions | Bendamustine hydrochloride d1‐2, 100 mg/m2, 28 days per cycle, at most 6 cycles versus Chlorambucil d1‐d2, d15‐d16, oral 0.4 mg/kg/day, 28 days per cycle, at most 6 cycles |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measures: Objective response rate Secondary outcome measures: progression‐free survival Duration of remission Overall survival The incidence and severity of adverse events |

| Starting date | March 2010 |

| Contact information | Dr Zhixiang Shen, 86‐021‐64370045 ext 665251 |

| Notes | NCT01109264 |

Eichhorst.

| Trial name or title | Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab or bendamustine and rituximab in treating patients with previously untreated B cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia |

| Methods | Phase III trial of combined immunochemotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) versus bendamustine and rituximab (BR) in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia |

| Participants | Patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia |

| Interventions | Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) versus bendamustine and rituximab (BR) |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measures: progression‐free survival rate after 24 months Secondary outcome measures: minimal residual disease, complete response rates and partial response rates Duration of remission Event‐free survival Overall survival Overall response rate Response rates in and survival times in biological subgroups Toxicity rates Quality of life Standard safety analysis |

| Starting date | September 2008 |

| Contact information | Barbara Eichhorst, MD 49‐221‐478‐4400 barbara.eichhorst@uk‐koeln.de |

| Notes | NCT00769522 |

Mundipharma Research.

| Trial name or title | A trial to investigate the efficacy of bendamustine in patients with indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) refractory to rituximab |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised Endpoint classification: safety/efficacy study Intervention model: parallel assignment Masking: open label Primary purpose: treatment |

| Participants | Patients with indolent B‐cell non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma that did not respond (stable disease or progressive disease) to rituximab or a rituximab‐containing regimen during or within 6 months of the last rituximab treatment |

| Interventions | Bendamustine compared to treatment of physician's choice |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measures: progression‐free survival. Defined as the interval between randomisation and disease progression or death. Secondary outcome measures: Overall response rate Complete remission or partial remission Duration of response Overall survival Safety and tolerability Change in health‐related quality of life measures (EORTC QLQ‐C30) |

| Starting date | February 2011 |

| Contact information | Margaret C Wilson and Jill Kiteley nfo@contact‐clinical‐trial.com |

| Notes | NCT01289223 |

Roche.

| Trial name or title | A study of mabThera added to bendamustine or chlorambucil in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (MaBLe) |

| Methods | Allocation: randomised

Endpoint classification: safety/efficacy study

Intervention model: parallel assignment

Masking: open label A randomised study to assess the effect on response rate of rituximab added to a standard chemotherapy, bendamustine or chlorambucil, in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia |

| Participants | Patients with CLL with progressive Binet stage B or C, ineligible for treatment with fludarabine. For second‐line patients, only pretreatment with rituximab and/or chlorambucil is allowed |

| Interventions | Rituximab 375 mg/m2 iv day 1 of cycle 1, followed by 500 mg/m2 iv every 4 weeks cycles 2 to 6 and bendamustine 90 mg/m2 (first‐line) or 70 mg/m2 (second‐line) iv, days 1 and 2 every 4 weeks, cycles 1 to 6 versus Rituximab (same schedule and dosage) and chlorambucil 10 mg/m2 po days 1 to 7 every 4 weeks, for up to 12 cycles |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measure: Complete response rate Secondary outcome measures: Overall response rate, complete response, partial response, stable disease, progression‐free survival, disease‐free survival, time to next leukaemia treatment, duration of response, overall survival, molecular response, minimal residual disease Adverse events, laboratory parameters |

| Starting date | March 2010 |

| Contact information | genentechclinicaltrials@druginfo.com |

| Notes | NCT01056510 |

Differences between protocol and review

Type of outcome measures:

We added all‐cause mortality assessed as dichotomous data as included published papers reported on mortality as dichotomous data, and there was not enough data to assess mortality (overall survival) as time to event outcome.

We deleted partial response (PR) and added overall response rate (PR + complete response (CR)).

Assessment of reporting bias:

We conditioned inspection of the funnel plot on the inclusion of at least 10 trials.

Subgroup analysis:

Comparator treatment

Alkylating agents based therapy

Purine analogues based therapy

Data synthesis:

For the primary outcomes we used a fixed‐effect model, and repeated the analysis using a random‐effects model as described in the protocol. Due to the clinical heterogeneity we decided to pool all other outcomes using a random‐effects model.

We did not pool results of progression‐free survival (PFS), overall response rate (ORR) and grade 3 or 4 adverse events due high statistical heterogeneity.

Contributions of authors

LV is the co‐ordinator of the review LV is responsible for constructing the search strategy, data collection, writing to authors for additional information and organising retrieval of papers. AG is responsible for undertaking searches in conference proceedings. AG, LV, RG and OS are responsible for screening search results, abstracting data from papers, screening retrieved papers against the inclusion criteria and appraising quality of papers; the latter review author was in charge, in case of disagreement. LV is responsible for entering data into RevMan 5 (RevMan 2011). AG, LV, RG, PR and OS participated in preparing and reviewing the protocol. AG, LV, PR, MD and OS participated in the analysis and interpretation of data.

All review authors participated in writing the review.

Declarations of interest

M. Dreyling received financial support for investigator‐initiated trials (Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Mundipharma, Pfizer, Roche Glycart), and honoraria for scientific advisory boards (Calistoga, Celgene, Janssen, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics, Roche) as well as educational presentations (Janssen, Mundipharma, Pfizer, Roche)

The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Herold 2006 {published data only}

- Herold M, Schulze A, Niederwieser D, Franke A, Fricke HJ, Richter P, et al. for the East German Study Group Hematology and Oncology (OSHO). Bendamustine, vincristine and prednisone (BOP) versus cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (COP) in advanced indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma: results of a randomised phase III trial (OSHO# 19). Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2006;132(2):105‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Knauf 2009 {published and unpublished data}

- Knauf U, Lissichkov T, Aldoud A, Herbrecht R, Liberati A, Loscertales J, et al. Bendamustine versus chlorambucil in treatment‐ naive patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: updated results of an international phase III study. Haematologica. 2009; Vol. 94 (Suppl 2):141. Abstract 0355.

- Knauf WU, Lissichkov T, Aldaoud A, Herbrecht R, Liberati AM, Loscertales J, et al. Bendamustine versus chlorambucil in treatment‐Naive Patients with B‐Cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B‐CLL): Results of an International phase III study. Blood 2007;110(11):609a. [Google Scholar]