Abstract

This study uses national pharmacy claims data to describes trends in prescriptions for HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) overall and by specialty between 2012 and 2018.

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends use of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for individuals at risk of acquiring HIV.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 1.1 million US individuals might benefit from PrEP,2 but only 7% of those used it in 2016.3 Clinicians have been slow to prescribe PrEP, citing concerns regarding its effectiveness outside a clinical trial setting, unintended consequences, and ambiguity surrounding which type of clinician is best suited to prescribe PrEP.4 Using a commercial insurance database, this study examined trends in the number of persons prescribed PrEP, prescriptions for PrEP, and specialty of prescribing clinicians.

Methods

We used the 2012-2018 MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental database, comprising national medical claims from US employer–provided health insurance with greater representation from the South, to identify persons prescribed 30 days or more of tenofovir-disoproxil-fumarate with emtricitabine (TDF/FTC). Loss of voluntary data contributors to MarketScan led to enrollee loss over time. Since TDF/FTC is indicated for HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and HIV postexposure prophylaxis in addition to PrEP, we excluded persons with any diagnostic codes or prescription drug treatments for HIV or HBV during the year before the first TDF/FTC prescription date. To ensure PrEP use (not postexposure prophylaxis use), we included TDF/FTC prescriptions with a supply of 30 days or more.

To ascertain prescriber specialty information, we matched pharmacy claims using the PrEP fill date with the service date of outpatient or inpatient claims for each patient. We further excluded refills, which could not be linked to medical claims, and excluded PrEP prescriptions matched with claims from more than 1 physician on the same day or missing physician specialty information. We categorized physician types into infectious disease, primary care physicians, and others. Primary care physicians included internal medicine, family practice, and other primary care physicians, which included medical physician, multispecialty physician group, geriatric medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology.5 Starting in 2015, when unique physician identifiers were available, we categorized physicians into HIV care and non–HIV care physicians, defined as those who provided care to patients infected with HIV or not based on HIV diagnosis codes from inpatient and outpatient claims. The University of Florida Institutional Review Board approved this study, including an informed consent waiver because the data were deidentified. Statistical significance for the yearly trend was defined as a 2-sided P < .05 using linear regression. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

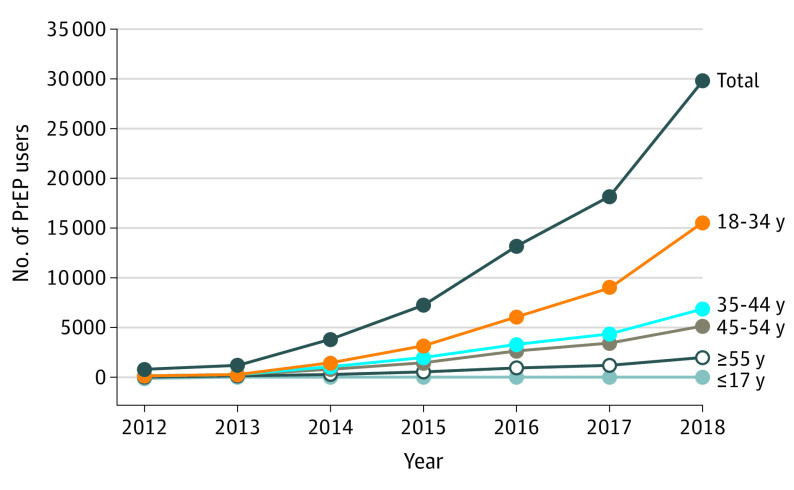

From 2012 to 2018, there were 47 132 PrEP users (397 913 prescriptions). The annual number of persons prescribed PrEP increased from 821 in 2012 (0.13 per 10 000 beneficiaries) to 29 799 in 2018 (10.56 per 10 000 beneficiaries) (P < .001) (Figure 1). Most were men (96%) and ranged in age from 18 through 44 years (73%).

Figure 1. Annual Number of PrEP Users by Age Group, 2012-2018.

The rates per 10 000 commercially insured beneficiaries prescribed HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) were 0.13 in 2012, 0.26 in 2013, 0.76 in 2014, 2.39 in 2015, 4.41 in 2016, 6.60 in 2017, and 10.56 in 2018. PrEP user counts were conducted by year, so the same PrEP user could be included in different years.

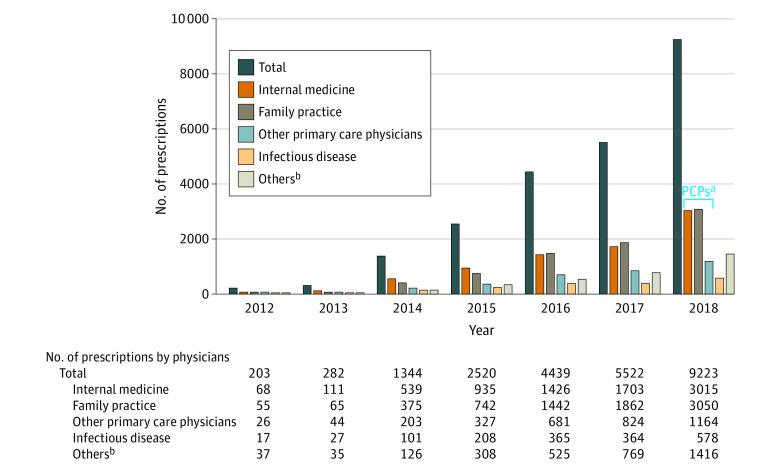

After excluding refills (56%), missing data (36%) (ie, 31% of pharmacy data not matched with outpatient or inpatient claims and 5% with missing physician type), or multiple clinicians (1%), 16 193 persons (23 533 prescriptions) were linked to physicians’ specialty information and 6529 had a unique physician identifier in the years 2015-2018. The percentage of missing data for physician specialty was consistent over time, ranging from 34% to 38%, and there were similar demographics between PrEP users with and without physician specialty information. The number of PrEP prescriptions increased from 203 in 2012 to 9223 in 2018 (P < .001) (Figure 2). Of 16 193 PrEP users linked to physician specialty information, primary care physicians prescribed 79% of PrEP while infectious disease physicians prescribed 7%. Of physicians prescribing PrEP, 42% were HIV care physicians, and they prescribed 64% of PrEP. HIV care primary care physicians prescribed 53% of PrEP.

Figure 2. Annual Number of Preexposure Prophylaxis Prescriptions by Physician Type, 2012-2018.

aPrimary care physicians (PCPs) include internal medicine, family practice, and others (medical physician, multispecialty physician group, geriatric medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology).

bMany other types of specialties, such as emergency medicine, pain medicine, urology, and psychiatry.

Discussion

The number of PrEP prescriptions among commercially insured beneficiaries steadily increased from 2012 to 2018, with primary care physicians prescribing most PrEP.

This study has several limitations. The numbers of PrEP prescriptions prescribed by physicians may be underestimated due to missing physician information or inability to match to a physician. This study included commercially insured persons only, so results may not be generalizable to other populations (eg, Medicaid). These results suggest that public health efforts to increase access to PrEP are needed, such as enhancing clinician education to identify appropriate candidates.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.US Preventive Services Task Force Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321(22):2203-2213. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Grey J. Estimates of adults with indications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by jurisdiction, transmission risk group, and race/ethnicity, United States, 2015. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):850-857.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2014-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(41):1147-1150. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6741a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silapaswan A, Krakower D, Mayer KH. Pre-exposure prophylaxis: a narrative review of provider behavior and interventions to increase PrEP implementation in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2):192-198. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3899-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu TL, Barritt AS IV, Weinberger M, Paul JE, Fried B, Trogdon JG. Who treats patients with diabetes and compensated cirrhosis. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]