Total cholesterol (TC) levels, triglyceride levels, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels are linked to coronary heart disease.1 Between 1999 and 2010, mean TC, triglycerides, and LDL-C levels declined in the United States, regardless of cholesterol-lowering medication use.2 We used 2013/2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey lipid data in conjunction with 1999 to 2012 data to determine whether earlier trends continued.

Methods |

Eight 2-year National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey cross-sectional cycles between 1999/2000 and 2013/2014 were analyzed for trends in TC levels, triglyceride levels, and LDL-C levels among adults (aged 20 years or older). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey uses a stratified, multistage probability design to provide a representative sample of the noninstitutionalized, civilian US population. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey was reviewed and approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Board. All participants gave written informed consent. In 2013/2014, the examination response rate for adults was 64% and ranged from 64% to 73% for the cycles between 1999/2000 and 2011/2012.

Cholesterol levels were analyzed on venous samples collected following a standardized protocol. Total cholesterol and triglyceride levels were measured using coupled enzymatic reactions.3 Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels were calculated using the Friedewald equation (LDL-C = TC − [high-density lipoprotein cholesterol + triglycerides/5]) for adults whose triglyceride levels did not exceed 400 mg/dL (to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113). Laboratory and methods changes regarding high-density lipoprotein cholesterol are discussed elsewhere.2 The laboratories conducting the testing participated in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Lipid Standardization Program (https://www.cdc.gov/labstandards/lsp.html) ensuring valid measurement comparability owing to slight instrumentation and reagent changes between 1999 and 2014. Lipid-lowering medication use was defined as currently taking medication to lower cholesterol. Examination sample weights were used for TC analysis. Morning fasting sample weights were used in the analysis of triglycerides and LDL-C. Standard errors were estimated by Taylor series linearization and confidence intervals were constructed using the Wald method for means. Significance was set at P < .05. Analyses were carried out with Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp).

Geometric means are presented for triglycerides because the distribution was heavily skewed. Arithmetic means are reported for TC and LDL-C. Estimates were age-adjusted using the direct method to the 2000 US Census projected population by age group (20–39 years, 40–59 years, and older than 60 years). Age-adjusted trends were tested with orthogonal contrasts matrices. Significant quadratic trends (P < .05) were found for triglycerides and LDL-C, implying the trends changed direction and/or magnitude. We confirmed changes in slope using JoinPoint analysis to find inflection points and piecewise linear regressions to test differences in slope on either side of these points. Age-adjusted linear regressions were plotted using marginal standardization to generate predicted values.

Results |

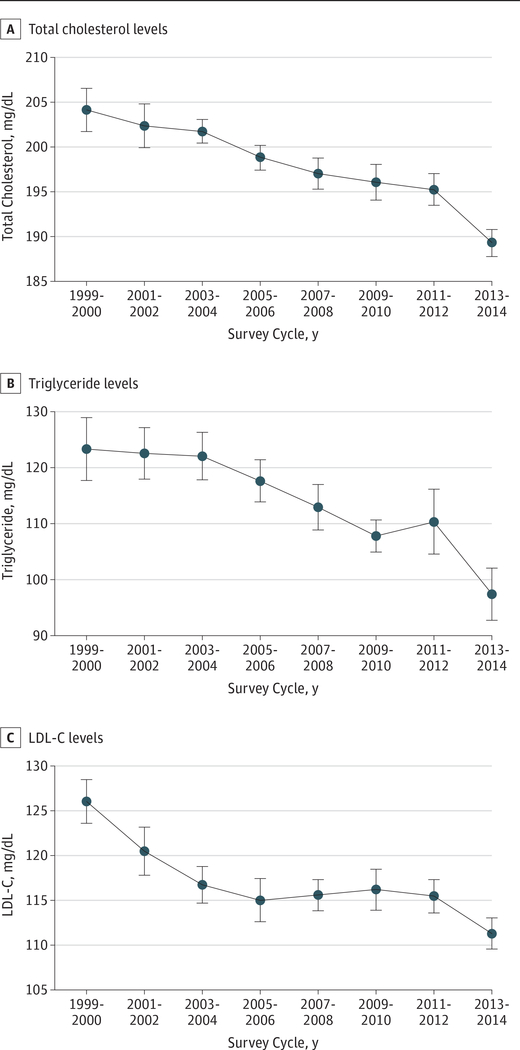

Thirty-nine thousand forty-nine adults 20 years or older had TC levels analyzed, and 17486 and 17096 had triglyceride levels and LDL-C levels analyzed, respectively. Age-adjusted mean TC decreased between 1999/2000 (204 mg/dL; 95% CI, 202–206 [to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259]) and 2013/2014 (189 mg/dL; 95% CI, 188–191 mg/dL) with significant linear (P<.001) but not quadratic trends and with a 6-mg/dL drop between 2011/2012 and 2013/2014 (Table; Figure, A). Age-adjusted geometric mean triglyceride levels decreased from 123 mg/dL (95% CI, 118–129 mg/dL) in 1999/2000 to 97 mg/dL (95% CI, 92–102 mg/dL) in 2013/2014 (P=.02 quadratic trend) with a 13-mg/dL drop since 2011/2012 (Figure, B). Mean LDL-C levels decreased from 126 mg/dL (95% CI, 124–129 mg/dL; to convert to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259) to 111 mg/dL (95% CI, 110–113 mg/dL) during the 8 survey cycles (P = .001 quadratic trend), with a 4-mg/dL drop between 2011/2012 and 2013/2014 (Figure, C). JoinPoint analysis and piecewise regressions found an inflection point at 2011/2012 for triglyceride values and 2 inflection points for LDL-C at 2003/2004 and 2011/2012, which reflect significantly steeper negative slopes. Between 1999/2000 and 2013/2014, the decreasing trends in TC, triglycerides, and LDL-C levels described in previous paragraphs were similar when stratified by lipid-lowering medications.

Table.

Age-Adjusted Arithmetic Mean Total Cholesterol, Geometric Mean Triglycerides, and Arithmetic Mean Low-Density Lipoprotein, by Lipid-Lowering Medication Status in US Adults Aged 20 Years and Older, 1999 to 2014a

| Header | Mean (95% CI) | P Value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | 2003–2004 | 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | 2011–2012 | 2013–2014 | Linear Trend, 1999–2000 to 2013–2014 | Quadratic Trend, 1999–2000 to 2013–2014 | |

| No.b,c | 4118 | 4691 | 4476 | 4481 | 5332 | 5696 | 4913 | 5342 | ||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dLd | 204 (202–206) | 202 (200–205) | 201 (200–203) | 199 (197–200) | 197 (195–199) | 196 (194–198) | 195 (193–197) | 189 (188–191) | <.001 | 0.13 |

| No.b,c | 369 | 479 | 649 | 640 | 981 | 1036 | 932 | 1061 | ||

| TC: LL meds, mg/dLd | 209 (200–218) | 212 (204–220) | 217 (198–235) | 206 (198–214) | 197 (187–207) | 186 (176–195) | 192 (181–204) | 191 (185–197) | <.001 | 0.67 |

| No.b,c | 3590 | 4001 | 3637 | 3652 | 4137 | 4491 | 3960 | 4268 | ||

| TC: no LL meds, mg/dLd | 205 (202–207) | 203 (200–205) | 203 (201–204) | 200 (199–202) | 200 (198–201) | 199 (196–201) | 199 (197–201) | 193 (191–195) | <.001 | 0.19 |

| No.b,e | 1819 | 2163 | 1952 | 1959 | 2347 | 2595 | 2286 | 2365 | ||

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, geometricd | 123 (118–129) | 122 (117–126) | 121 (117–126) | 117 (113–121) | 112 (108–116) | 107 (105–110) | 110 (104–115) | 97 (92–102) | <.001 | 0.02 |

| No.b,e | 149 | 215 | 295 | 287 | 442 | 473 | 451 | 481 | ||

| Triglycerides: LL meds, mg/dLd | 146 (139–153) | 151 (122–187) | 152 (126–183) | 175 (141–218) | 143 (127–160) | 131 (108–158) | 122 (104–142) | 116 (100–136) | 0.001 | 0.02 |

| No.b,e | 1614 | 1852 | 1578 | 1601 | 1808 | 2059 | 1826 | 1875 | ||

| Triglycerides: no LL meds, mg/dLd | 121 (116–127) | 120 (115–125) | 118 (113–123) | 113 (109–116) | 110 (106–114) | 105 (102–108) | 107 (102–113) | 94 (90–99) | <.001 | 0.07 |

| No.b,f | 1772 | 2095 | 1900 | 1907 | 2296 | 2550 | 2244 | 2332 | ||

| LDL-C, mg/dLd | 126 (124–129) | 121 (118–123) | 117 (115–119) | 115 (113–117) | 116 (114–117) | 116 (114–118) | 115 (114–117) | 111 (110–113) | <.001 | 0.001 |

| No.b,f | 144 | 210 | 285 | 273 | 422 | 461 | 437 | 475 | ||

| LDL-C: LL meds, mg/dLd | 117 (113–122) | 121 (110–132) | 119 (91–147) | 122 (114–130) | 120 (106–135) | 107 (96–119) | 107 (89–126) | 107 (99–116) | 0.03 | 0.21 |

| No.b,f | 1574 | 1793 | 1540 | 1564 | 1778 | 2028 | 1798 | 1849 | ||

| LDL-C: no LL meds, mg/dLd | 127 (125–130) | 122 (119–124) | 119 (116–121) | 117 (114–120) | 118 (116–120) | 119 (116–122) | 119 (117–121) | 115 (113–117) | <.001 | 0.002 |

Abbreviations: LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein; LL meds, lipid-lowering medication; TC, total cholesterol.

SI conversion factor: To convert low-density lipoprotein cholesterol to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; to convert total cholesterol to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglycerides to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113.

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; estimates are weighted.

Unweighted sample size.

Thirty-nine thousand forty-nine adults 20 years or older had TC levels analyzed and 37 883 have information on lipid-lowering medications.

95% CI calculated using Wald method for means.

Seventeen thousand four hundred eighty-six adults 20 years or older had triglyceride levels analyzed and 17 006 have information on lipid-lowering medications.

Seventeen thousand ninety-six adults 20 years or older had LDL-C levels analyzed and 16 631 have information on lipid-lowering medications.

Figure 1. Age-Adjusted Total Cholesterol, Triglyceride, and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) Trends for US Adults Aged 20 Years and Older, 1999 to 2014.

A, Predicted total cholesterol levels and 95% confidence intervals in a sample size of 39 049. B, Predicted log-transformed triglyceride levels and 95% confidence intervals; log-transformed values were exponentiated after the regression, sample size of 17 406. C, Predicted LDL-C levels and 95% confidence intervals in a sample size of 17 096. Figure generated using marginal standardization from age-adjusted linear regression models. Data source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

SI conversion factors: To convert LDL-C to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; to convert total cholesterol to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglycerides to micromoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113.

Discussion |

Between 1999/2000 and 2013/2014, a significant decline in triglyceride levels and LDL-C levels occurred with significantly steeper negative slopes observed between 2011/2012 and 2013/2014. A steady decreasing trend continued in 2013–20142 in mean TC levels.

Removal of trans-fatty acids in foods has been suggested as an explanation for the observed trends of triglycerides, LDL-C levels, and TC levels.4 With increased interest in triglycerides for cardiovascular health,5 the continued drop of triglycerides, LDL-C levels, and TC levels at a population level represents an important finding and may be contributing to declining death rates owing to coronary heart disease since 1999.6

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

Correction: There was an error in the author affiliations and an error in the Results section. Dr Rosinger should have the affiliation “Epidemic Intelligence Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevencion, Atlanta, Georgia,” and Drs Rosinger, Carroll, Lacher, and Ogden should have the affiliation “Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, Maryland.” Additionally, in the first paragraph of the Results section, in the second sentence, the age-adjusted mean total cholesterol level in 2013/2014 should have been 189 mg/dL, not 89 mg/dL. This article was corrected online. This article was corrected on January 7, 2016.

Contributor Information

Asher Rosinger, Epidemic Intelligence Service, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, Maryland; Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, Maryland.

Margaret D. Carroll, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, Maryland.

David Lacher, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, Maryland.

Cynthia Ogden, Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, Maryland.

References

- 1.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel iii). JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll MD, Kit BK, Lacher DA, Shero ST, Mussolino ME. Trends in lipids and lipoproteins in US adults, 1988–2010. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1545–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Health Statistics/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: MEC laboratory procedures manual; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_13_14/2013_MEC_Laboratory_Procedures_Manual.pdf. Published 2013 Accessed April 7, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vesper HW, Kuiper HC, Mirel LB, Johnson CL, Pirkle JL. Levels of plasma trans-fatty acids in non-Hispanic white adults in the United States in 2000 and 2009. JAMA. 2012;307(6):562–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby P Triglycerides on the rise: should we swap seats on the seesaw? Eur Heart J. 2015;36(13):774–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma J, Ward EM, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Temporal trends in mortality in the United States, 1969–2013. JAMA. 2015;314(16):1731–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]