Abstract

Myomectomy scar pregnancy (MSP) is a rare disease, which is defined as a gestational sac located within a previous myomectomy scar. MSP is an uncommon late complication of uterine fibroids after myomectomy. We report a case where the implantation site matched the site of the previous myomectomy, and review the existing literature. A 28-year-old pregnant woman presented with vaginal bleeding. She was diagnosed with MSP by ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging, and then underwent laparotomic enucleation. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful. Taking into account the findings in our case and the seven other reported cases of MSP, we propose that MSP can be divided into three types and that surgical enucleation of the pregnancy mass is an effective treatment.

Keywords: Myomectomy scar pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin, vaginal bleeding, gestational sac, surgical enucleation, uterine fibroids

Introduction

Uterine fibroids commonly occur in women of reproductive age.1 In women with management of pregnancy, uterine rupture during labor has been reported in patients with prior myomectomy. A special type of ectopic pregnancy (EP), as a rare long-term complication after myomectomy, has gradually attracted attention.

Myomectomy scar pregnancy (MSP), which is characterized by an implantation into the site of a myomectomy scar, is an extremely rare form of EP.2 The diagnosis of MSP is mainly based on an imaging examination. We report a detailed case of MSP and also review previously published cases.

Case report

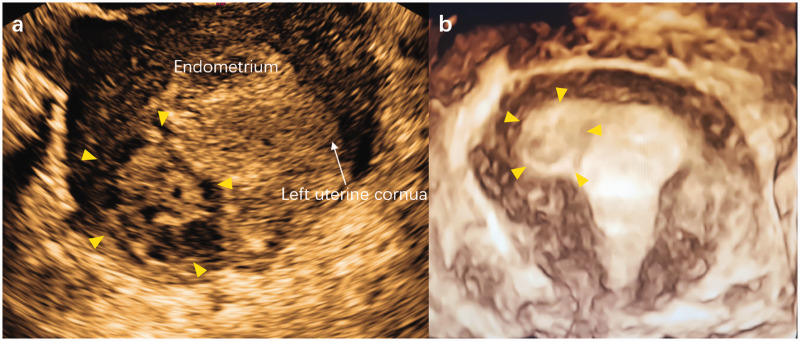

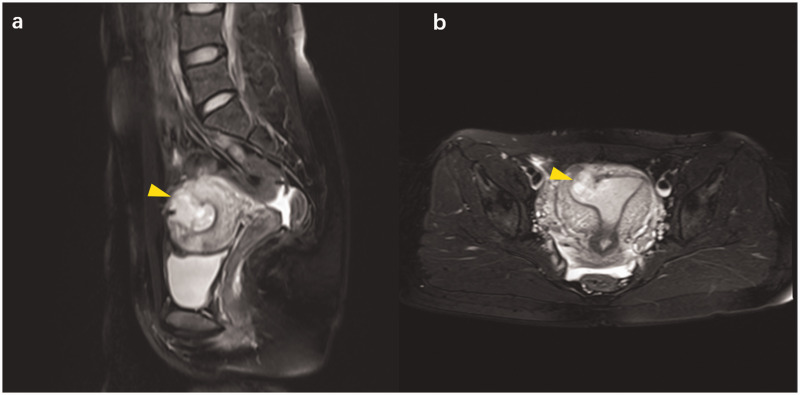

A 28-year-old, Chinese, nulligravida woman presented to our hospital with painless vaginal spotting for the past 15 days, with a history of 6 weeks of amenorrhea and a quantifiable beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin (β-HCG) level of 52,104 IU/L. A subsequent transvaginal ultrasound examination showed a hybrid-echo mass of 3.7 × 2.8 × 2.7 cm in the right horn of the uterus and it connected with the uterine cavity (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the ultrasound findings of an EP of 2.2 × 2.5 × 3.2 cm in the myometrium extending from the uterine cavity to the myometrium (Figure 2). A repeat serum β-HCG test, which was performed 48 hours after the initial test, showed a level of 64,080 IU/L. This finding represented a 23% rise in the β-HCG level.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound imaging shows a hybrid-echo mass in the right horn of the uterus (yellow arrow). (a) Transverse section of the uterus; and (b) three-dimensional image of the uterus.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvic cavity showing a mass of mixed signal (yellow arrow), which connects with the uterine cavity, in the fundus near the right uterine cornua. (a) Sagittal views of magnetic resonance imaging; and (b) transverse views of magnetic resonance imaging.

The patient had a history of laparoscopic myomectomy 2 years previously. A solitary submucous myoma approximately 7 cm in diameter at the fundal region toward the right side was removed. Intraoperatively, the actual endometrium was breached, and the incision was closed with a two-layer polyglactin suture. A postoperative examination with ultrasound showed a normal uterus without fibroids. She was physically fit and did not receive any medication before this presentation.

Subsequently, an exploratory laparotomy with endotracheal general anesthesia was performed. This examination showed 20 mL of blood in the pelvic cavity and a bluish-purple mass with a diameter of 3 cm in the right horn of the uterus, which was consistent with the location of the previous myoma. The great omentum was adherent high on the posterior uterine wall, which obscured visibility.

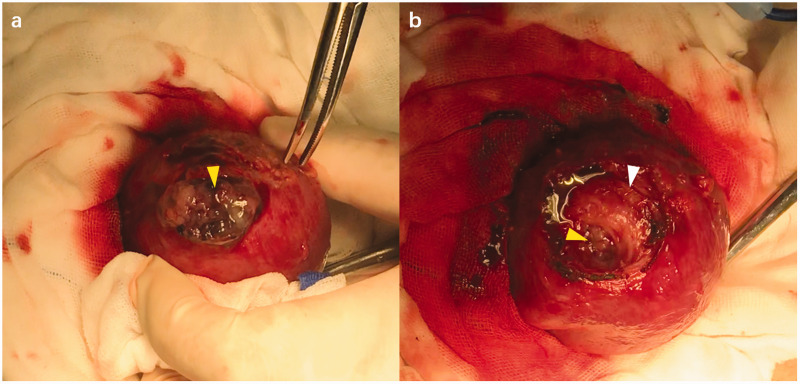

Our laparotomic technique was as follows. After removing the adhesion, a 1-cm superficial fissure was visible on the mass. A 3-cm transverse incision was made on the bottom of the uterus just above the pregnancy mass, and then the trophoblastic tissues bulged (Figure 3a). Ring forceps were used to pull the chorionic villi out of the intramural portion of the uterus. After the gestational product was completely removed, an unexpected dead space, which communicated with the uterine cavity, was visible (Figure 3b). In consideration of the high initial β-HCG level and uncertainty about residue of invisible chorionic villi, methotrexate (MTX) at a dose of 50 mg was slowly injected into the local myometrium. This was followed by repair of the wound in the uterine wall through interrupted and continuous sutures layer by layer. The amount of intraoperative hemorrhage was 50 mL.

Figure 3.

Laparotomic view of our case of myomectomy scar pregnancy. (a) Bulging trophoblastic tissues (yellow arrow) can be seen; and (b) dead space in the myometrium (white arrow) and a channel to the uterine cavity (yellow arrow) can be seen.

Postoperative recovery was uneventful. The level of β-HCG measured on postoperative day 1 was 22,946 IU/L. Pathological diagnosis confirmed the presence of villi and decidua. The woman was discharged from hospital at 7 days postoperatively and followed up in the outpatient department. The level of β-HCG had decreased to normal 4 weeks after the operation.

The patient’s specific information was completely de-identified in the manuscript. Therefore, documentation of ethics was not required. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication. We followed the CARE guidelines.

Case review

All English articles on MSP were searched in online databases, including PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science. The search strings were ((((((((intramural ectopic pregnanc*[Text Word]) OR intramural ectopic pregnanc*[Title/Abstract])) OR ((scar ectopic pregnanc*[Text Word]) OR scar ectopic pregnanc*[Title/Abstract])) OR ((ectopic pregnanc*[Text Word]) OR ectopic pregnanc*[Title/Abstract])) OR ((Scar Pregnanc*[Text Word]) OR Scar Pregnanc*[Title/Abstract])) OR ((intramural Pregnanc*[Text Word]) OR intramural Pregnanc*[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((((hysteromyomectomy[Text Word]) OR hysteromyomectomy[Title/Abstract])) OR ((Myomectomy[Text Word]) OR Myomectomy[Title/Abstract])). We also manually reviewed the reference lists of the included studies to collect more eligible articles. After reviewing all cases and published English literature, we found seven MSP cases.2–8 The clinical findings for each case are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of published myomectomy scar pregnancy cases.

| No. | Authors and year | Region | Age (years) | Previous details of myomectomy | GA at diagnosis | Mode of conception | Symptom | Present USG findings | Present MRI/CT findings | Type | Treatment | Subsequentpregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Park et al.3 2006 | Korea | 35 | Abdominal myomectomy for a 7 × 5 × 4-cm, intramural myoma; two-layer sutures were performed | 37th day post-ET | IVF | Painless vaginal spotting | GS within the subserosal area of the posterior uterine wall | — | III | Laparoscopic enucleation | Successful singleton pregnancy with frozen ET, which was 3 months after operation |

| 2 | Wong et al.4 2010 | Australia | 33 | Abdominal myomectomy for multiple fibroids; the endometrium was not breached | Not mentioned | Spontaneous conception | Not mentioned | A mass on the right posterior aspect of the uterine fundus, with bulging into the serosa | — | III | Four MTX doses administered initially locally and then intramuscularly | Unsuccessful conception |

| 3 | Bannon et al.5 2013 | USA | 27 | Abdominal myomectomy for a large, left-sided, posterior leiomyoma | 10 weeks | Spontaneous conception | Asymptomatic | A GS was located in the posterior left lateral wall of the uterus surrounded by myometrium | CT was consistent with USG | II | Suction curettage. A single dose of systemically MTX. Da Vinci-assisted laparoscopic enucleation. | Not mentioned |

| 4 | Paul et al.6 2018 | India | 31 | Laparoscopic myomectomy for a 7 × 7-cm intramural myoma toward the left side; the endometrium was not breached; two-layer sutures were used | 9 weeks | Spontaneous conception | Asymptomatic | A GS of 3.6 × 2.4 cm was found in the fundal region toward the left side | — | II | Laparoscopic enucleation | Not mentioned |

| 5 | Ishiguro et al.7 2018 | Japan | 41 | Laparoscopic myomectomy was performed twice in an interval of 2 years, and it was performed for multiple myomas in the uterine body; the endometrium was not breached; two-layer sutures were used | 8 weeks | IVF | Severe abdominal pain | A GS was in front of the uterus | — | III | Laparoscopic enucleation | Not mentioned |

| 6 | Vagg et al.8 2018 | Australia | 34 | Abdominal myomectomy was performed for a 6.3 × 6.0 × 5.6-cm intramural fibroid in the right lateral posterior uterine wall and a smaller 5.8 × 3.0 × 1.9-cm fibroid adjacent to the external cervical os was found | 12 weeks | Spontaneousconception | Pain in the right iliac fossa and vaginal discharge | A live intramural ectopic pregnancy, with a surrounding thin 3-mm layer of myometrium, was found | A GS (8.0 × 7.9 × 7.0 cm) contained a mobile fetus within the myometrium of the right uterine cornua | II | Abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy | — |

| 7 | Liu et al.92019 | China | 34 | Abdominal myomectomy for a hysteromyoma (5.4 × 3.9 cm) in the left fundus of the uterus | Not mentioned | Spontaneous conception | Asymptomatic | A GS was located in the posterior myometrium of the uterine fundus near to the left cornua | — | II | Hysteroscopy and laparoscopic enucleation | Not mentioned |

| 8 | Our case2019 | China | 28 | Laparoscopic myomectomy for a 6.8 × 7.2 × 5.7-cm submucous myoma on the right side of the uterine fundus; the endometrium was breached; two-layer sutures were used | 6 weeks | Spontaneous conception | Painless vaginal spotting | A hybrid echo-mass of 3.7 × 2.8 × 2.7 cm was located in the right horn of the uterus | An EP of 2 × 2.5 × 3.2 cm was observed in the myometrium | I | Laparotomic enucleation and a single dose of local MTX | — |

USG, ultrasonography; MTX, methotrexate; GA, gestational age; GS, gestational sac; IVF, in vitro fertilization; ET, embryo transfer; EP, ectopic pregnancy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography

Discussion

MSP refers to an uncommon type of EP, and it is defined as a gestational sac (GS) located within a previous myomectomy scar. MSP is an infrequent late complication of uterine fibroids after surgery. To the best of our knowledge, only seven cases diagnosed with MSP have been previously reported.2–8

Of the total number of eight cases including our case, two were the result of spontaneous conception and six of in vitro fertilization. Among the patients, the age ranged from 27 to 35 years, and all cases were diagnosed on the basis of ultrasonic testing, with or without MRI/computed tomography. Two of eight (25%) patients were admitted because of painless vaginal spotting and two of pain in the iliac fossa or abdomen, while three were asymptomatic. With regard to treatment modalities, surgical removal of the pregnancy mass (dilatation and curettage, laparoscopic enucleation, hysteroscopy, or hysterectomy) and/or medical management (local or intramuscular injection of MTX) were used in the cases.

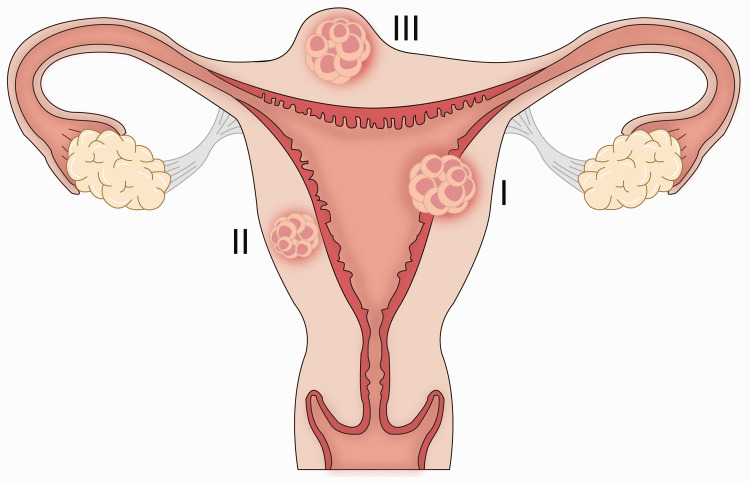

According to the characteristics of the ultrasonic signal, we propose that MSP can be divided into three types (Figure 4) as follows: (I) GS/products of conception partially breaching the endometrial–myometrial junction, connected with the uterine cavity; (II) GS/products of conception completely breaching the endometrial–myometrial junction, well circumscribed by the myometrium; and (III) GS/products of conception projecting out of the uterus, surrounded by myometrium and serosa. Type II is the most common in MSP. Case 8 (our case) is first case of MSP that had a GS that connected with the uterine cavity.

Figure 4.

Three types of myomectomy scar pregnancy.

The pathogenic mechanisms of MSP remain unclear. We speculate that the etiology of MSP in our case was implantation of the embryo through a microscopic fistula that formed after the myomectomy scar.

Early diagnosis for MSP is crucial because it may lead to uterine rupture and life-threatening massive hemorrhage in a short period of time, which may require hysterectomy. However, MSP lacks a specific clinical manifestation and can be easily misdiagnosed as uterine myomas, missed abortion (case 3), trophoblastic disease, or nonintramural EP, especially cornual pregnancy. Therefore, carefully reviewing the initial history and physical exam records is important. The diagnostic process of MSP involves serial β-HCG measurements and an ultrasound examination. MRI also provides a good assist method for diagnosis. Furthermore, contrast-enhanced ultrasound may help effectively monitor blood perfusion and identify the implantation site of the embryo.9

Because of the rarity of MSP, the standard treatment guidelines currently remain unclear. However, once the diagnosis is established, appropriate treatment should be carried out without delay before complications occur. Clinical doctors must be vigilant for cases of MSP. Furthermore, hospitals should be equipped to deal with emergency conditions and a blood bank, or prompt transfer to a higher level hospital is recommended. Management and individual therapy are administrated to each case based on availability of resources, the physician’s experience, and the patient’s preference. Among the eight cases of MSP, surgical enucleation of the pregnancy mass appeared to be the preferable option. Tight sutures of the uterine wall incision, including the endometrium, myometrium and serosa, could potentially reduce the incidence of MSP. However, because of the limited cases of MSP, specific recommendations to prevent MSP are not currently available. More clinical cases of MSP are necessary to address this issue. Our findings will hopefully play an enlightening role and attract the attention of clinicians.

In conclusion, although MSP is extremely rare, it should not be ignored in case of unknown located pregnancy. The individualized treatment plan for this condition must be carefully considered. The key to early diagnosis of MSP is to increase awareness of diagnosis and improve accuracy of imaging at the diagnostic level. Currently, surgical exploration appears to be preferable for confirmation of the pregnancy site and the certainty of efficacy of treating MSP.

Author contributions

DHL conceived the study. DHL, SYL, and LQ performed the operation and follow-up of the patient. WCS created the figures and table. LLZ and XYY drafted the article and DHL revised it critically. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the version to be published.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

Grant support was provided by the Project Foundation of Hangzhou Science and Technology Bureau (20170533B59), Hangzhou Health Science, Technology Plan (2017A54), Zhejiang Medical and Health Technology Plan (2018248116; 2020KY620) and Medical Health Science, Technology Project of Hangzhou Women’s Hospital (2016YJA02).

References

- 1.Stewart EA, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Catherino WH, et al. Uterine fibroids. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2: 16043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul PG, Mannur S, Shintre H, et al. Myomectomy scar pregnancy: a rare complication of myomectomy. J Gynecol Surg 2018; 34: 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park WI, Jeon YM, Lee JY, et al. Subserosal pregnancy in a previous myomectomy site: a variant of intramural pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2006; 13: 242–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong KS, Tan J, Ang C, et al. Myomectomy scar ectopic pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2010; 50: 93–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannon K, Fernandez C, Rojas D, et al. Diagnosis and management of intramural ectopic pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013; 20: 697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishiguro T, Yamawaki K, Chihara M, et al. Myomectomy scar ectopic pregnancy following a cryopreserved embryo transfer. Reprod Med Biol 2018; 17: 509–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vagg D, Arsala L, Kathurusinghe S, et al. Intramural ectopic pregnancy following myomectomy. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2018; 6: 2324709618790605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu D, Gu X, Liu F, et al. Application of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for scar pregnancy cases misdiagnosed as other diseases. Clin Chim Acta 2019; 496: 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong X, Yan P, Gao C, et al. The value of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in the diagnosis of cesarean scar pregnancy. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 4762785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]