Abstract

We describe a 55-year-old woman with severe idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (mean pulmonary artery pressure 71 mmHg, pulmonary vascular resistance 30 WU at diagnosis five months ago), who was diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) and experienced a relatively mild course with symptoms resembling a common cold. To date, information about the clinical course of COVID-19 in pre-existing pulmonary arterial hypertension is lacking, and it is thus unknown whether pulmonary arterial hypertension belongs to the risk factors of severe COVID-19 disease.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial hypertension, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus, COVID-19

Case description

A 55-year-old never-smoking woman was diagnosed with severe idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension by right heart catheterization in fall 2019 with the following hemodynamic measurements: mean pulmonary artery pressure 71 mmHg, pulmonary artery wedge pressure 13 mmHg, cardiac index 1.4 l/min/m2, pulmonary vascular resistance 30 WU.1 The diagnosis was suspected due to progressive dyspnea for several years and echocardiography, which revealed severe right heart failure with a trans-tricuspid pressure gradient of 100 mmHg, enlarged right-sided chambers, D-shaping of the left ventricle, normal ejection fraction and normal size of the left atrium. Chronic thromboembolic diseases were excluded by CT-pulmonary angiography. The patient was in dyspnea NYHA III, her 6-minute walk distance was 465 m and the NT-proBNP was 4700 ng/l. The patient was treated for mild hypertension with an angiotensin-receptor blocker and with thyroid replacement therapy for hypothyreosis and had no other comorbidities. The patient declined continuous intravenous prostaglandin therapy, and thus a combination of macitentan (10 mg daily) and tadalafil (20 mg daily, increased to 40 mg daily after 14 days) combined with diuretic therapy was initiated. The patient herewith improved subjectively to NYHA II, the 6-minute walk distance increased to 570 m, and antihypertensive therapy was stopped in regard of low-normal blood pressure. The patient went to visit her family in Guatemala over Christmas time. At the end of January 2020, she felt well in dyspnea NYHA I, the NT-pro BNP decreased to 421 ng/l, the trans-tricuspid-pressure gradient to 35 mmHg, ergospirometry revealed a peak oxygen uptake of 14.3 ml/min/kg (57% predicted) and the patient was able to go back to work.

On 3 March 2020, the patient called our pulmonary hypertension unit due to symptoms of a common cold, stuffy nose, muscle- and headache, slightly elevated body temperature of 37.9℃, and general weakness. She denied cough and resting dyspnea. Symptomatic therapy was recommended at that time.

On 11 March 2020, the patient called again still suffering from rhinitis, reduced general health state, and muscle aches. Upon request, she told that she suffered from dyspnea and anxiety mainly during the night, but no fever. As Sars-CoV-2 infections started to be diagnosed in Switzerland at that time, we asked the patient to be brought to the entrance of the outpatient clinic, where she was expected by a fully protected doctor, who immediately provided her with a protective surgical mask and disinfectant for the hands.

Medical history revealed that her symptoms started a day after her weekly visits to the church the 1 March and that around 30 other persons that regularly visit her church suffered from symptoms of common cold, some of which were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2. The patient confirmed that she had followed home quarantine together with her husband, who similarly suffered from symptoms of a common cold last week. The patient’s symptoms slightly improved over the last days, but in addition to the nightly dyspnea attacks with anxiety, she also had sore throat and loss of appetite, but neither suffered from cough nor fever.

Clinical and additional exams

The patient was in a good health state, blood pressure 112/71 mmHg, heart rate 66/min, SpO2 98% on ambient air, no leg edema, no jugular vein distension, normal heart, and lung auscultation. Her throat was slightly reddish; a nasopharyngeal swap for virus including SARS-CoV-2 was taken under highly protective equipment.

Blood examination revealed a normal hematogram, a normal C-reactive protein and procalcitonin; the NT-proBNP was normal with 284 ng/l.

In lack of an indication in a patient without signs of pneumonia, we did not perform a chest X-ray and sent the patient back home with a repeated thorough instruction to follow home quarantine.

Diagnosis of intercurrent upper respiratory tract illness

The nasopharyngeal swap returned positive for a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Course of the disease

The patient was called on 12 March 2020 to inform her about the positive SARS-CoV-2 result. She reported a good health state but was anxious.

She was called again on 13 March, when the patient expressed increasing dyspnea and anxiety, so the decision was made to hospitalize her. She arrived with protective equipment with the ambulance, was still in good health state, SpO2 97% on ambient air, without signs of respiratory or cardiac failure.

She was observed on the ward under source isolation precautions for three days and afterwards discharged back to home quarantine until three days after full recovery.

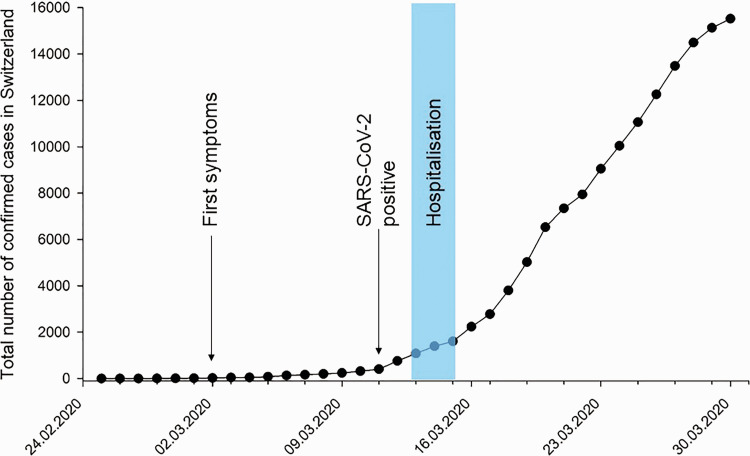

Fig. 1 shows the clinical course of this patient in relation to the total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Switzerland.

Fig. 1.

Clinical course of this patient in relation to the total number of confirmed COVID-19-cases in Switzerland.

Discussion

This patient with severe idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension, which responded very well to an initial oral combination therapy, suffered from relatively mild SARS-CoV-2 infection resembling a common cold. At her initial call, COVID-19, the respiratory disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, was only occasionally found in Switzerland and without a travel history to endemic areas or contact history to known cases, we treated this patient for a common cold. Already one week later, with raising numbers of SARS-CoV-2 infections all over Switzerland, our suspicion substantially increased, and the outpatient clinical examination including the nasal swap was performed with all precautions in order not to let the infection spread. The patient’s symptoms were consistent with a relatively mild but typical course of SARS-CoV-2 infection and fortunately not fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome.2 Her recurrent nightly dyspnea were interpreted as reactive anxiety disorder, supported by the fact that they disappeared after reassurance during the hospitalization. The patient had at least one known risk factor for COVID-19 disease, namely the history of arterial hypertension. However, we saw her only with low normal blood pressures, even before having initiated therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension.3 Whether pulmonary arterial hypertension per se is a risk factor of severity in SARS-CoV-2 infection is not known, as we did not find a published case so far and pulmonary arterial hypertension was not listed in published comorbidities.3,4 That is why we believe that it is important to share the disease course of this patient with the pulmonary hypertension community and improve the care of our patients.5

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS., et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1801913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 2020; 323: 1239–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y., et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with Covid-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 2000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395: 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan JJ, Melendres-Groves L, Zamanian RT., et al. Care of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Pulmon Circ 2020; 10: 2045894020920153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]