Abstract

Implant debris generated by wear and corrosion is a prominent cause of joint replacement failure. This study utilized Fourier Transform InfraRed spectroscopic Imaging (FTIR-I) to gain a better understanding of the chemical structure of implant debris and its impact on the surrounding biological environment. Therefore, retrieved joint capsule tissue from five total hip replacement patients was analyzed. All five cases presented different implant designs and histopathological patterns. All tissue samples were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. Unstained, 5μm thick sections were prepared. The unstained sections were placed on BaF2 windows and deparaffinized with xylene prior to analysis. FTIR-I data were collected at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 using an Agilent Cary 670 spectrometer coupled with Cary 620 FTIR microscope. The results of study demonstrated that FTIR-I is a powerful tool that can be used complimentary to the existing histopathological evaluation of tissue. FTIR-I was able to distinguish areas with different cell types (macrophages, lymphocytes). Small, but distinct differences could be detected depending on the state of cells (viable, necrotic) and depending on what type of debris was present (polyethylene (PE), suture material and metal oxides). Although, metal oxides were mainly below the measurable range of FTIR-I, the infrared spectra of tissues exhibited noticeable difference in their presence. Tens of micrometer sized polyethylene particles could be easily imaged, but also accumulations of submicron particles could be detected within macrophages. FTIR-I was also able to distinguish between PE debris, and other birefringent materials such as suture. Chromium-phosphate particles originating from corrosion processes within modular taper junctions of hip implants could be identified and easily distinguished from other phosphorous materials such as bone. In conclusion, this study successfully demonstrated that FTIR-I is a useful tool that can image and determine the biochemical information of retrieved tissue samples over tens of square millimeters in a completely label free, non-destructive, and objective manner. The resulting chemical images provide a deeper understanding of the chemical nature of implant debris and their impact on chemical changes of the tissue within which they are embedded.

1. Introduction

Wear debris and corrosion products generated from total hip replacements (THR) can cause osteolysis or adverse local tissue reactions (ALTR) in some patients, often leading to premature implant failure1–4. The type of tissue response can be best diagnosed and characterized by histopathological analysis, which allows for an accurate determination of present cell types but cannot characterize the chemical structure of prominent particulate debris such as polyethylene (PE) and chromium orthophosphate (CrPO4) particles5,6. A direct analysis of the chemical structure of the debris is difficult with limited analytical options. Previous studies have employed a scanning electron microscope (SEM) or transmission electron microscope (TEM) equipped with energy-dispersive x-ray (EDS) detector which provide spectra and a detailed mapping of the elemental distribution7–9. However, chemical structures, i.e. bonding information, cannot be characterized with these methods. Moreover, the isolation of particulate debris is often needed for examination, which requires additional treatment, potentially leading to chemical alteration of the sample10,11. For the analysis of PE debris within tissue, researchers rely heavily on its birefringent nature. In some cases, suture fragments can potentially be mistakenly identified as PE debris as they are also birefringent under polarized light, thus it is up to the experience of the examiner of the histological slides to distinguish PE from other birefringent materials. TEM analysis allows for an accurate characterization of particulate debris in terms of chemical composition and crystallinity by means of electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) and electron diffraction pattern analysis12–14. However, TEM allows only for the analysis of local phenomena at a high magnification, but it is not an ideal tool for the analysis of particle laden tissue samples that are usually tens of millimeters in size.

As the number of yearly performed total joint replacements is still on the rise15,16, it is important for the orthopedic research community to better understand the chemical structure of implant debris and the corresponding histopathological patterns. As research on accurate blood and serum biomarkers is increasing17–20, it is important to note that histopathological analysis methods remain the most accurate option21. However, an accurate histopathological diagnosis is strongly dependent on the observer’s experience level. Therefore, it is important to explore additional characterization techniques for the determination of the chemical structure of implant debris and the affected tissue.

Fourier Transform InfraRed spectroscopic Imaging (FTIR-I) is a promising technique for providing chemical information on cells and tissue for clinical diagnosis and research22–24. FTIR-I spectra provide spatially resolved (to a few microns) total chemical compositional information, which for biological materials, is typically the macromolecular content of the sample—proteins, lipids, nucleic acids and carbohydrates. For non-biological materials (polymers, organics and inorganics), the resultant FTIR spectra can be used to confidently determine chemical identification or information on chemical changes via functional group analysis. The development of multichannel focal plane array (FPA) detectors allows for advanced infrared (IR) imaging of biological matter25. The yielded hyperspectral image enables rapid analysis of the chemical distribution within biological samples with a high spatial resolution. No sample preparation is needed in addition to the standard preparation for histology samples. Moreover, FTIR-I allows samples to be analyzed in a label-free, non-destructive, and objective manner, whereby the IR beam itself does not harm or change the tissue samples, allowing for further examination after the imaging26. FTIR-I can provide a fast method to localize and characterize wear and corrosion debris in context with histopathological findings by measuring the ‘fingerprint’ spectrum (1800 – 900 cm−1) with characteristic frequencies of different chemical bonds27.

It was the goal of this study to present to the orthopedic research community this new powerful imaging approach and its capability in characterizing particulate wear debris, corrosion products, cell types, and other foreign bodies imbedded within joint capsule tissue samples from THR patients with different implant types. To this effect, a retrieval study was conducted on 5 THR cases with different histopathological patterns, which included a detailed characterization of IR spectra of the joint capsule tissue itself and foreign bodies captured within.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample selection

2.1.1. Histopathological characterization of samples

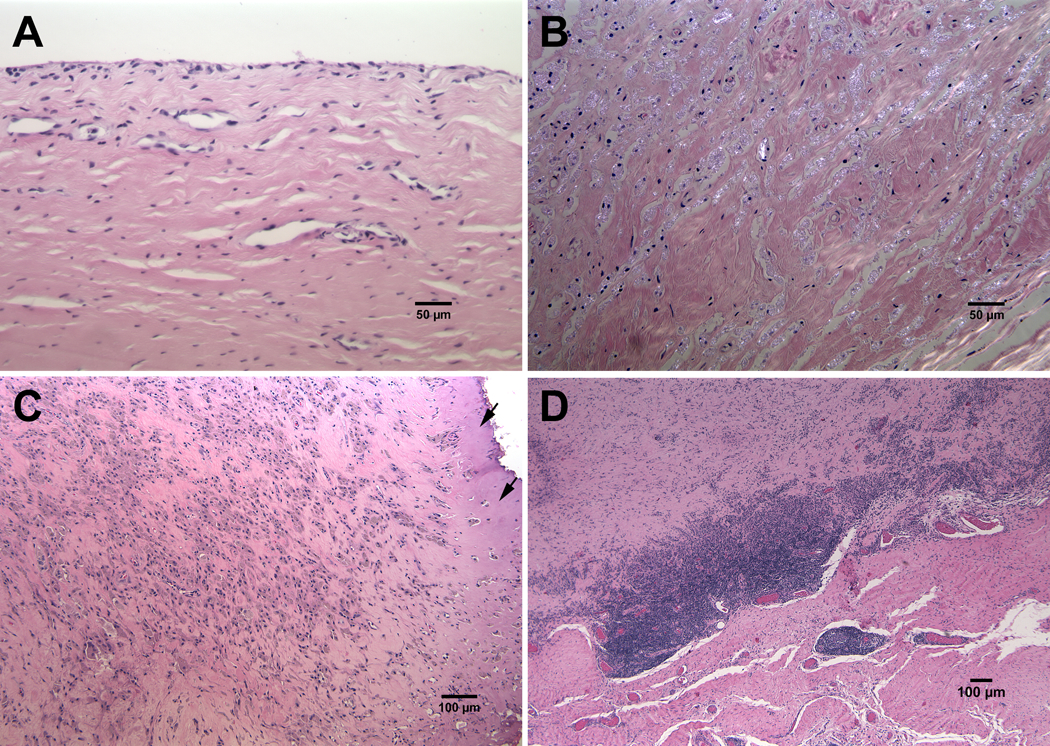

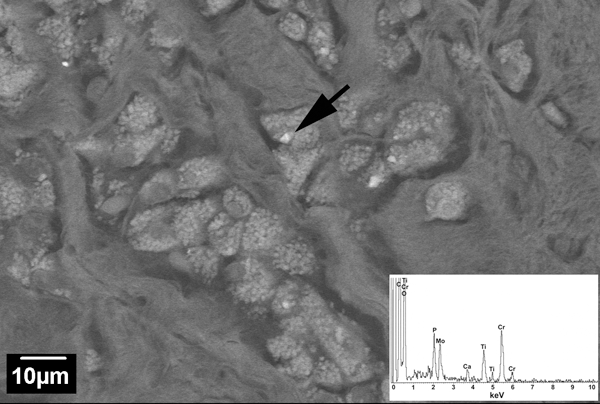

It is a standard practice at the Biocompatibility and Implant Pathology Laboratory at Rush to histopathologically analyze postmortem retrieved tissue and tissue from revision patients with suspicion of ALTR, osteolysis or other abnormal conditions. For this study, the joint capsule tissue from 5 THR patients was studied. The cases were selected to represent different bearing couples, femoral stem alloys and different histopathological findings. Two cases were retrieved postmortem, and three cases were surgically retrieved at revision surgery (Table 1). All tissue samples were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE). 5μm-thick sections were made and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Light and polarized microscopy (Microphot FXA, Nikon, Melville, NY) was used to characterize the predominant histological pattern seen for each case. The slides were evaluated for the presence and extent of inflammatory cells such as particle-laden macrophages and lymphocytes. The quality of the synovial surface and presence of necrosis was also assessed for each case. The joint capsule tissues from the 5 cases exhibited distinct histological patterns. Case 1 (Figure 1A) consisted of a normal fibrous-type synovial tissue containing a layer of one to three synoviocytes and rare particle-laden macrophages. Cases 2 and 3 (Figure 1B, 1C) had predominately macrophage-dominated foreign body reactions. In Case 2, the majority of the particle-laden macrophages contained birefringent particles. Large spindle-shaped birefringent particles were also seen in multi-nucleated giant cells. Lymphocytes were absent. The synovial surface was intact, and no necrosis was present. Case 3 had a marked presence of particle-laden macrophages. Some of the macrophages contained birefringent particles. A few perivascular and diffuse lymphocytes were also present. The synovial lining was replaced by an organizing fibrin exudate. SEM/EDS analysis revealed a mixture of different particles. The majority of particles appeared to be Cr- and Ti-oxide (Figure 2). However, CoCrMo, Cr-phosphate, Mo-oxide were present as well. Case 4 (Figure 3) had a mixed inflammatory pattern with a marked presence of lymphocytes and particle-laden macrophages which were adjacent to large areas of necrotic tissue. Within the necrotic areas, translucent green particles were seen. A fibrin exudate covered the synovial surface. An accumulation of dense, black particles was seen in one area of the exudate. SEM/EDS analysis confirmed that the majority of particles were Ti-oxide. However, there were also peaks for molybdenum and zirconium indicating that TMZF® alloy particles were generated as well. Additionally, the presence of chromium, phosphorous and oxygen peaks indicated the presence of Cr-phosphate and -oxide. The pattern seen in Case 5 (Figure 1D) was lymphocyte-dominated, consisting of both marked perivascular and diffuse lymphocytes. Plasma cells were also present, as well as a few macrophages. No particles were seen within the tissue. A fibrin exudate covered the surface of the joint capsule.

Table 1.

Histopathological findings of tissue samples in all cases.

| Case Number | Design, Manufacturer | Bearing Couple | Stem Alloy | Neck alloy | Sleeve alloy | Retrieval type | Time in situ (months) | Histopathological Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | VerSys Fiber Metal Taper, Zimmer | MoP | Ti6Al4V | N/A | N/A | Postmortem | 94.1 | Normal |

| #2 | Prodigy, DePuy | MoP | CoCrMo | N/A | N/A | Postmortem | 221.8 | Macrophage-dominated foreign body reaction |

| #3 | Profemur Plasma Z, WMT | MoM | Ti6Al4V | CoCrMo | Ti6Al4V | Surgically Retrieved | 116/ 72.2 | Marked presence of macrophages, few lymphocytes, ALTR |

| #4 | Accolade, Stryker | MoP | TMZF | N/A | N/A | Surgically Retrieved | 102.7 | Marked presence of macrophages and lymphocytes, tissue necrosis |

| #5 | Rejuvenate Modular Neck, Styker | CoP | CoCrMo (HAp coated) | CoCrMo | N/A | Surgically Retrieved | 12.4 | Marked presence of lymphocytes and few macrophages, ALTR |

Figure 1.

A: Joint capsule section Case 1 from had a normal fibrous synovial appearance (magnification, X200). B: A marked presence of particle laden macrophages containing birefringent particles was seen in Case 2 (cross polarization, magnification, X200). C: A marked presence of particle-laden macrophages was also seen in Case 3. The synovial lining was replaced an organizing fibrin exudate (arrows) (magnification X100). D: Low power image demonstrating the marked perivascular and diffuse lymphocytic reaction seen in Case 5 (magnification, X40). (All: hematoxylin and eosin stain)

Figure 2.

Backscattered electron (BSE) SEM image from joint capsule of Case 3 with multiple particle-laden macrophages (magnification X1000). Inset: EDS spectrum of particle indicated by the arrow revealed the particles were mixed oxides of chromium, titanium and molybdenum.

Figure 3.

The mixed inflammatory pattern of Case 4. A: Perivascular and diffuse lymphocyte-dominated area (magnification, X100). B: Particle-laden macrophage area containing black particles (magnification, X100). C: necrotic region of the capsule containing translucent green particles (magnification X200). (All: hematoxylin and eosin stain)

2.1.2. Implant type and damage

Implant surfaces were visually examined under a stereo light microscope (SMZ-U Stereoscopic Zoom Microscope, Nikon), and results are tabulated below (Table 2). The examination included the articulating surfaces of the acetabular liner and the femoral head, the taper surfaces of the femoral head and femoral stem, and if applicable the taper surfaces of the sleeve adapter or the second modular interface of the neck-stem taper of dual modular stems. The damage score of all metal taper surfaces was scored analog to the Goldberg method with a combined fretting and corrosion score28,29. Cases that exhibited considerable damage under the light microscope were further analyzed in a SEM (JSM-6490 LV, JEOL, Peabody, MA) to determine specific damage patterns. Case 1 was a metal-on-polyethylene (MoP) with a highly cross-linked PE liner. The liner only exhibited minimal wear. The dominant wear feature was polishing. There was no damage on the femoral head articulating surface. The stem and head taper surfaces had no damage as well (Score 1). Case 2 was also a MoP hip with a conventional PE liner. The linear exhibited mild to moderate damage. There was a distinct wear scar that was also mainly characterized by polishing and some pits. There was no damage on the taper surfaces (Score 1) and no damage on the femoral head. Case 3 was a metal-on-metal (MoM) hip with a titanium stem and neck, and a CoCrMo sleeve adapter. There were distinct wear scars on both the head and cup articulating surfaces. Damage was mainly characterized by oriented scratches. The sleeve had only mild damage on either taper surface (Score 2). The trunnion of the head/neck taper had local fretting corrosion damage. The male neck/stem taper and the female stem taper exhibited severe fretting damage and plastic deformation. Case 4 was a MoP hip. The femoral head exhibited negligible material loss, the PE cup exhibited no clear wear scar, but its articulating surface exhibited strong plastic deformation, creep, and multiple scratches. The CoCrMo head taper exhibited a distinct circumferential band of damage characterized by scratches and fretting marks. The TMZF® stem taper was completely worn away in a similar fashion as earlier described for this implant type30. Material loss was not limited to the taper but extended well into the femoral neck area of the stem. Case 5 was a dual modular metal-on-ceramic (CoP) hip with a CoCrMo stem with HAp coating. The PE liner was not available for analysis. The ceramic head exhibited no wear, but metal transfer from the femoral neck component onto the head taper was observed. The head/neck taper had only minimal damage, whereas both the male and female taper surfaces of the all CoCrMo neck/stem junction exhibited severe fretting damage (Score 4).

Table 2.

Description of damage on all articulating and taper surfaces for all cases. (N/A: not applicable)

| Case Number | Cup | Head | Head taper | Sleeve taper (male) | Sleeve taper (female) | Stem taper | Neck/Stem taper (male) | Neck/Stem taper (female) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | no to minimal wear | no wear | minimal damage | N/A | N/A | minimal damage | N/A | N/A |

| #2 | moderate wear | no wear | minimal damage | N/A | N/A | minimal damage | N/A | N/A |

| #3 | severe wear (distinct wear scar) | severe wear (distinct wear scar) | mild fretting corrosion | minimal damage | minimal damage | minimal damage | severe fretting | moderate fretting corrosion |

| #4 | plastic deformation, creep, scratches | no wear | severe fretting corrosion | N/A | N/A | completely worn away | N/A | N/A |

| #5 | not available | no wear (Ti-alloy transfer) | minimal damage | N/A | N/A | minimal damage | severe fretting corrosion | severe fretting corrosion |

2.2. Sample preparation

For the chemical analysis of the tissue samples, additional 5 μm sections were cut from the paraffin embedded samples. One unstained section was placed on a 25×2 mm BaF2 disc (Spectral Systems, Hopewell Junction, NY) for FTIR-I analysis. The adjacent section was mounted on a high-purity vitreous carbon planchet for EDS analysis (INCA Energy 350, Oxford Instruments, Concord, MA). The unstained sections were deparaffinized with xylene prior to analysis.31

2.3. FTIR-I methods

2.3.1. Data Acquisition

FTIR-I data were collected at a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 using an Agilent Cary 670 FTIR spectrometer coupled with Cary 620 FTIR microscope (Agilent Technologies-Santa Clara, CA, USA). The system is equipped with a 128×128 element mercury-cadmium-telluride (MCT) Focal Plane Array (FPA) detector, which—by using the 15x, 0.62NA objective—has a projected pixel size of 5.5×5.5 μm2 at the sample plane and an overall field of view 704×704 μm2. For every acquired hyperspectral image, 96 scans were collected in transmission mode, averaged, and the ratio was computed against a 128-scan reference background to yield absorbance spectra. Data within the range between 3850–850 cm−1 were saved. The resultant single tile image consists of a total of 16,384 spatially resolved spectra covering the whole field of view. The mosaic mode was employed to extend the field of view. Images were generated by automatically moving the stage from the initially selected image position to the last to allow sequential individual scanning. A mosaic image was generated by stitching all image tiles together to provide one image within the square millimeter size range. Imaging data were then exported to a CytoSpec V2.0.04 (CytoSpec, Berlin, Germany) for further processing. In some cases, specific regions of interest (ROIs) were analyzed in more detail by operating in single point MCT mode within the microscope with an aperture (mask) of 25×25 μm2. This mode provides a higher spectral resolution at 2 cm−1, thus providing a more detailed description of narrow peaks locally. An Agilent micro-ATR (attenuated total reflection) accessory was employed to conduct measurements on suture reference samples for the comparison of spectrum from embedded suture debris. The micro-ATR has an internal reflection element made of Germanium. To ensure a good contact between the tip and sample, an unused suture was taped on a glass slide and monitored through the software window in real time. The measurement parameters were the same as imaging under transmission mode.

2.3.2. Data Processing

Hyperspectral images were baseline-corrected using an 8-point second order polynomial fitting algorithm to compensate the scattering effect32,33. A linear subtraction of the baseline was performed to normalize the region between 1800–850 cm−1, thus correcting the off-set. Quality test was applied through calculating the signal-to-noise (SNR) ratio of individual spectrum, and to eliminate those that do not fulfill a threshold SNR ratio, which defined as a ratio of signal from Amide I region (1700–1600 cm−1) and the noise in the region between 1900–1800 cm-1. A follow-up noise reduction was achieved by conducting a principal component (PC) analysis with the first 25 PCs. After the pre-processing, images could be viewed using either a univariate or multivariate approach. For the univariate analysis, data was imaged at a specific wavenumber or a collective wavenumber range. The absorbance of chemical bonds at corresponding position was displayed as a heat map based on their relative intensity, thus revealing the biochemical distribution of a designated chemical bond. The multivariate approach is to cluster the major components across the whole image by comparing the individual spectrum of every pixel. Agglomerative hierarchal cluster analysis (HCA) is commonly used to cluster spectral data34–36. HCA is a hard clustering method that reconstructs the image based on the similarities of spectra by presenting a pseudo-colored image with a selected number of clusters. Another novel multivariate approach is fuzzy C-means analysis (FCA), considered to be a soft clustering approach. FCA has been previously employed to cluster biological hyperspectral data34,37. This method allows a spectrum of an individual pixel to belong to several clusters, thus working at both the spatial and spectral domain38. This paper provides an example by using the FCA method to generate a composition (merged) image, analog to Bonifacio et al39, for comparison with histological imaging. These clustering methods allow for the characterization of the biological environment with both their locations and characteristic spectra, which could later be compared with stained histological images for cross reference.

3. Results

3.1. FT-IR imaging of tissue

The typical IR spectrum of joint capsule tissue was mainly characterized by peaks related to the collagen network40. The characteristic peaks consisted of amides I/II (1700–1500 cm−1), amide III (1300–1180 cm−1), and other biological functional groups41 (Figure 4). Areas with a strong cell presence exhibited variations of the spectrum compared to viable areas without cells or necrotic sites likely indicative of differences in macromolecular cellular composition.

Figure 4.

Typical IR spectrum of collagen fibrous tissue. Peaks refer mainly to different amide and lipid groups.

Polyethylene debris:

PE particle were identified in Case 2 and 4 by strong characteristic absorbance signals: δas(-CH2) at 1462 cm−1, δs(-CH2) at 1473 cm−1, νs(-CH2) at 2850 cm−1, and νas(-CH2) at 2920 cm−1 42. The most dominant occurrence of PE debris was observed in Case 2. A close-up polarized light microscope image of the tissue sample showed a macrophage-rich area (Figure 5A), which could be more clearly seen under polarized light microscopy of the H&E section (Figure 1B). Chemical images of such areas were plotted to demonstrate the considerable PE absorbance intensity (Figure 5B and C) using an integrated peak around the strong C-H stretching vibration around 2850 cm−1. The chemical image at 1657 cm−1 visualized regions that showed a strong amide I (protein) presence (Figure 5B), and the chemical image at 2850 cm−1 (Figure 5C) illustrated the presence of polyethylene. In Figure 5C, it can be seen that PE occurs with different intensities. Red dotted areas in the chemical image correlated to accumulations of particles in the range of several micrometers which can usually also be seen under a polarized light microscope due to its birefringent nature. Yellow-orange areas are less intense, but still exhibited the characteristic PE peaks, thus indicating that accumulations of very fine PE particles were present within macrophages. The same type of birefringent feature was also observed in Case 4 (macrophage-rich areas) to a lesser extent. Case 2 also exhibited numerous large (~200 μm), elongated polyethylene particles (Figure 5D and 5E). Such large particles provide for a purer PE spectrum because there is little influence of peaks relating to the tissue itself due to the large particle size and thickness. The corresponding spectra diagram showed the spectral differences between un-affected collagenous tissue and particle-laden macrophages (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

A) Light microscopic image of joint capsule tissue of Case 2. This area had a prominent occurrence of macrophages and birefringent particles (Figure 1B). B) and C) Chemical images at around 1657, 2850 cm−1 respectively. The former is mainly attributed to amide I (Protein), whereas the latter correlates to the presence of PE. Areas with a prominent amide I occurrence have a lower PE occurrence and vice versa (arrows represent the pixel where the spectrum come from). D) Light microscopic and E) chemical image of a large (~400 μm) PE particle. The chemical image is plotted at 2850 cm-1. F) Diagram of the corresponding spectra illustrating the relevant spectra.

Suture debris:

Numerous birefringent particles were observed within the samples of Cases 3 and 4. Although these particles appeared similar to PE wear debris under the light microscope, it was identified as surgical suture debris with FTIR-I analysis (Figure 6). Chemical images were displayed at 1725 cm−1, which is assigned to ν(C=O), the carbonyl stretching vibration. In Case 3 these particles had mainly a round or elongated shape (Figure 6A, B), whereas in Case 4 particles were larger, had a ribbon-like shape and were found in necrotic areas (Figure 6C, D). A suture reference spectrum was achieved by using the fixed-ATR mode as described above on a suture sample. The reference spectrum corresponded well to the spectrum of suture found within the tissue. The additional peaks in the suture embedded spectrum could be assigned to amide absorbance from proteins within the tissue. To better illustrate this spectral variance since some crystalline polymers can have narrower peaks, several spectra were acquired with the single point mode at a resolution of 2 cm-1. In Case 4, by subtracting the spectrum (purple) of necrotic tissue from the spectrum (red) of an embedded suture particle, a spectrum (green) could be achieved that matched the reference sample well (Figure 6E), yet with more peak details and a stronger intensity.

Figure 6.

IR Light microscopic images and chemical images at 1725 cm−1 of tissue samples from Case 3 (A, B) and Case 4(C, D). Particles were smaller and either round or elongated in Case 3, whereas Case 4 had large ribbon-like particles that were located within necrotic areas. (E) Infrared spectra: (1) shows a spectrum of a suture particle embedded in viable tissue (Case3). It has comparable peaks to those of the suture reference spectrum (2). Spectrum (3) was taken on a large ribbon-like particle embedded in necrotic tissue (Case 4), and spectrum (4) corresponds to the nearby necrotic tissue itself. By subtracting spectrum (4) from (3) a spectrum can be generated that resembles the reference suture spectrum (2) more closely.

Phosphates:

The particulate CrPO4 appeared translucent and greenish in color under the light microscope and was identified in all cases except Case 1. FTIR-I data demonstrated characteristic spectra of CrPO4 by chemical imaging at an integrated peak area of 1080–1030 cm−1 43–45. Case 4 exhibited numerous large (40–100 μm) particles (Fig. 7A and B). In Case 5 similar but much fewer particles were found as well. Cases 2 (Fig. 7C, D), and 3 (Fig. 7E, F) also exhibited CrPO4 particles, but they were not as numerous as in Case 4. In Case 2, CrPO4 particles were found surrounded by macrophages, while in Case 3 and 4 CrPO4 particles resided only in necrotic areas. A yellowish flake-like particle (Figure 7C) exhibited a comparable feature to CrPO4 in the chemical image, but was identified as a bone fragment with a distinct spectrum (Fig. 7G) 46. In general, two types (Type 1 and Type 2) of CrPO4 particles could be observed, which could be distinguished by the relative intensity of the wide peak stretching from 3700 to 3000 cm-1. For Case 5, special attention was given to the potential presence of Hydroxyapatite (HAp) due to the HAp coated stem. HAp can be characterized by ν1(PO43-) at 965 cm−1 and ν3(PO43-) at 1000~1120 cm−1 with strong H-O-H stretching from 3280 cm−1 to 3550 cm−1 43,47–51. However, no HAp debris was observed.

Figure 7.

A) Light microscopic image of the tissue sample from Case 4 showing large foreign particles (middle black arrow). B) The corresponding chemical image to A); by imaging at 1080–1030 cm−1 it was shown that the foreign particle was CrPO4. It appears that the particle has fractured, thus leaving a hole. C) Image of tissue sample from Case 2, and D) the corresponding chemical image plotted at 1080–1030 cm−1 show a large CrPO4 particle. E, F) Case 3: light microscopic and chemical image plotted at 1080–1030 cm−1. The light microscopic image shows a bright (white arrow) and a dark particle (black arrow). The chemical image indicates a similar chemical structure for both particles, but the actual spectra (G) show that the bright particle has a sharp peak, whereas the darker particle has a dome shaped peak at phosphate related region between 1080 and 1030 cm-1. The former is confirmed as bone, and the latter is indicative of chromium phosphate. The spectra between 3700 and 3000 cm−1 also exhibit a difference in their width, which is related to the amount of hydrogen bonded water.

Macrophage and lymphocyte rich areas in presence of metallic or metal oxide particles:

Some samples had a strong macrophage response without the presence of PE particles as in Case 3. The area with a marked macrophage response was analyzed using FTIR-I (Figure 8A). Under transmitted visible light, the macrophage-dominated area was revealed as darker dotted zones which were easily identified. Chemical images were viewed at around 1657 and 1081 cm−1 (Figure 8B and 8C) to highlight the variation of protein (amide I peaks) and nucleic acid (phosphorous group). Spectra of macrophage-rich areas showed a gradual increase of the peak at 1150–1000 cm−1 compared with collagenous tissue (Figure 8D) which is related to a combination of different phosphate and nucleic acid groups. The previous SEM/EDS analysis showed an accumulation of mixed oxide (chromium, titanium and molybdenum) and phosphate particles within the macrophages (Figure 2). The corresponding peaks for these oxides were outside of the measurable FTIR-I range, which is 3850–850 cm-1. For instance, titanium oxide (rutile phase) has peaks around 722, 590, 525 and 471 cm−152. In Case 4, areas with strong lymphocytic infiltration, macrophage-dominated response, viable collagenous fibers, and necrosis were previously characterized through histology (Figure 3 A-C). The lymphocyte-rich areas (Figure 9A1–3) showed a similar infrared signature as viable areas, except for an increase in symmetric ν(PO2-) at 1081 cm−1 corresponding to nucleic acid (Figure. 9 C). Necrotic tissue had a comparable spectrum to areas with viable macrophages (Figure 9 B1–3). However, a detailed comparison from 2nd derivative spectra (Figure 9 C: inlet) of amides I/II related peaks revealed a shift to lower wavenumbers, indicating a change in the protein secondary structure (alpha-helix and beta-sheet mainly). The peak position of amide A also seemed to shift which could be attributed to the disruption of H-bonds or broken side chains (N-H bond) which is typical of collagen relative to other tissues53. Case 5 also exhibited a strong lymphocytic reaction as first shown in the histologic section (Figure 1D). The optical image (a 3×2 tiled mosaic) of the ROI was captured (Figure 10A), and FCA was applied to the imaging data (Figure 10B). The resulting composition image had a similar appearance as the light microscopic image of an H&E section from the corresponding region. The resulting image can be easily distinguished in three areas with different types of spectra: 1) collagenous tissue without lymphocytes, 2) lymphocytes-rich areas, and 3) collagenous tissue in direct vicinity of lymphocytes, which potentially altered the chemistry to some extent (Figure 10C).

Figure 8.

A) 2×2 mosaic image of the macrophage-rich area of Case 3 (Figure 1C). B) Chemical image plotted at around 1657cm−1 indicates a strong presence of amide I. C) The chemical image plotted at around 1081 cm−1 refers to the presence of nucleic acid, thus indicating the presence of macrophages (see Figure 1C). No foreign bodies could be directly detected despite strong macrophage presence. This is related to the fact that most particles were shown to be metal oxides (Figure 2), thus outside of the measurable range for detector. D) Diagram of peaks at different areas as marked in A). A distinct peak variation can be seen at the location of macrophages at spectral range from 1150–1000 cm-1. This spectral range can refer to different phosphate and nucleic acid groups. Area around 1720 cm−1 will present a shoulder. Peaks variation at these locations may be indirect indicators for macrophage particle uptake, which is supported by the EDS analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 9.

A-1) 1×2 mosaic image of the macrophage laden area of Case 4 (Figure 3B). This area also exhibited a large number of Ti-oxide particles. The corresponding chemical images at A-2) 1081cm−1 and A-3) 1657 cm−1 confirm again the presence of cells within an amide I-rich environment. B-1) This 1×2 mosaic images was taken in the lymphocyte laden area of the same sample (Figure 3A). The chemical images at B-2) 1081cm−1 and B-3) 1657 cm−1 also indicate the presence of cells due to the presence of nucleic acid. C) A diagram showing four typical spectra of relevant areas of this tissue sample: macrophage laden areas, necrotic areas, lymphocyte laded areas and the viable collagenous tissue. In the spectral range of 1500 −1700 cm−1 (inlets: zoom-in spectra and their corresponding 2nd derivative spectra), a red shift can be observed for macrophage and lymphocyte laden tissue compared to collagenous areas. Necrotic tissue also had a similar shift. The shift may due to its potential conformation change. The peak at 1081 cm−1 was highest for the lymphocyte laden areas indicating strong proliferation. The macrophage laden areas showed a lower peak that was similar to necrotic areas.

Figure 10.

A) Light microscopic image of the area of interest. B) Pseudo-color composition image derived from fuzzy c-means clustering (FMC) method. Salmon colored areas indicate the presence of collagenous tissue, whereas cornflower blue (less densely packed) and green (densely packed) colored areas represent lymphocyte-rich areas. Red colored areas indicate collagenous tissue that lymphocytes are directly embedded within. C) Diagram of corresponding spectra extracted from B).

4. Discussion

It was the goal of this study to characterize wear debris and corrosion products within retrieved joint capsule tissue from THR patients by means of FTIR imaging. The results demonstrate that FTIR-I is a powerful tool that is complementary to the histopathological evaluation of tissue. FTIR-I not only provides information on the chemical structure of foreign bodies, but also chemical changes in the surrounding biological environment in a stain-free, non-destructive, quantitative and objective manner.

For the discussion of the FTIR-I data, one must consider that the pre-processing of raw FTIR-I data—especially the baseline correction—is crucial to yield reasonable results in context with the pathological analysis. One has to be aware that some biological samples can generate high scattering effects due to the holes and other discontinuity of the sample. Since a universal approach is lacking, a previous publication advised to choose a correction method based on visually spotted issues, correspondingly 54. In this study, the most common distortion encountered was a mildly sloping baseline, especially at higher wavenumbers (3850–1800 cm−1). Therefore, a second-order polynomial baseline correction followed by an offset correction satisfied our purpose.

The results of this study demonstrated subtle changes of the IR response to joint capsule tissue depending on its condition (viable or necrotic) and the presence of inflammatory cell types such as macrophages and lymphocytes. Chemical differences within the collagen matrix of the tissue can best be detected by slight shifts of the amide I and II peaks, whereas the presence of different cell types could be determined by differences in the peaks corresponding to nucleic acid (e.g., PO2-, PO43-). Thus, FTIR-I cannot only serve to locate and characterize foreign bodies, but also characterize the biological environment. In cases where foreign bodies could not be identified (e.g. metal oxides), the deviation of the spectral information of the biological environment may give an indirect indication of their presence. For example, the spectra of macrophages in Case 3 exhibited a widened absorbance band at 1150–1000 cm−1, and a shoulder at around 1720 cm−1 (Figure 8D). This spectrum may result from the presence of metal oxides as observed by EDS (Figure 2). The absorbance at the lipids zone also seems to increase compared to un-affected collagenous fibrous tissue55.

Large PE particles (μm range) could be easily identified, mostly correlating to findings of birefringent particles under polarized light microscopy. Interestingly, FTIR-I was also able to detect the accumulation of very fine PE debris within single macrophages (Figure 5C). Considering the fact that the majority of PE particle have a size (mean equivalent circle diameter between 200–400nm) far below the FTIR-I’s pixel size of 5.5 μm56–58, and disseminate across the entire section, it is likely that the detected peaks observed through FTIR-I resulted from particle accumulation within macrophages through the pathway of phagocytosis. The fact that the macrophage-dominant areas corresponded to considerable PE signals while tissue free from macrophages showed higher absorbance at amide I, supports this finding (Figure 5B and 5C). Thus, in cases with PE wear and taper corrosion, FTIR-I can uniquely and effectively be used to determine whether a macrophage response is primarily triggered by PE debris. The absence of PE characteristic peaks indicates that it is likely that metal or metal oxide particles have triggered the macrophage response instead.

The observed CrPO4 particles were characteristic for THRs undergoing modular junction corrosion as first described by Urban et al.44,59, and later confirmed by others14,45,60. Under the light microscope, gaps in the tissue could be easily noticed between particles, which were likely caused by fracturing of the brittle, glass-like chromium phosphate particles during sectioning 61. Two types of CrPO4 spectrum were identified, which can be attributed to different extents of Hydrogen-bonded water (Figure 7). Type 2 CrPO4 has a larger amount of bonded crystalline water than Type 1 as indicated by the broader band between wavenumbers 3700 and 3000 cm-1. It is important to note that FTIR-I enables the precise distinction of CrPO4 from other phosphates or phosphorous materials such as bone and HAp as demonstrated by the detection of a bone fragment in Case 3. Previous studies have shown that CrPO4 particles can be yellow-golden in color62, but based on the results of this study it seems possible that such particles are bone fragments which can easily be misidentified as CrPO4, thus demonstrating another benefit of FTIR-I with its ability to spatially and chemically characterize and identify particles

Case 4 exhibited considerable corrosion damage on the head taper surface, as well as a strong lymphocyte presence. However, the strong macrophage response appeared to be mainly driven by the excessive material loss generated from the TMZF® taper that has also been described by others for this implant type30. Titanium alloy debris and titanium oxides, which were detected by EDS in the macrophage dominated areas of this case, was below the detection range of the MCT FPA detector as mentioned above. Case 3 was a MoM bearing, which also exhibited some CrPO4 particles. These particles appeared to originate from moderate corrosion at the head-neck junction and severe fretting corrosion at the neck/stem junction. Overall, this case did not show any clear peaks within the macrophage-rich areas. This implant exhibited most prominently wear on both CoCrMo alloy articulating surfaces, and fretting damage on the female taper of the Ti6Al4V dual modular stem. Wear particles generated from MoM articulations were reported to have a size range of 30 to 100 nm under well-functioning conditions13,63. These particles are well below the few micron spatial resolution of our FTIR-I diffraction limits. In that case the majority of particles consist of Cr-oxide13,63. Under severe contact conditions (e.g. edge loading) larger particles are also generated, and maintain the CoCrMo alloy composition13, but may degrade to Cr-oxide over time by macrophages through phagocytosis depending on the particle size64. The observed fretting damage on the dual modular taper stem would indicate the generation of Ti-alloy and Ti-oxide debris. The EDS analysis of the corresponding tissue did reveal the presence of all types of particles (CoCrMo, Ti6Al4V, Cr-oxide and Ti-oxide). None of these particles can be chemically detected by FTIR-I directly. However, subtle changes (e.g. peak shift, shape, scattering, and intensity) of the biological environment detected by FTIR-I may give an indication as to what type of foreign body is present. The exact interpretation of fine spectral changes and how they relate to tissues and cells requires further investigation. FCA was shown to be a valuable tool to detect histopathological features (e.g. cell presence), and to image chemical changes within tissue. Although being in its early stages, clustering techniques are promising to characterize chemical changes induces by foreign particles, and may even provide a pathway to histopathological diagnosis.

Furthermore, FTIR-I was able to distinguish suture debris from PE particles, which is not always obvious using polarized light microscopy only. Whereas, in some cases particles can easily be identified as suture due to long fibrillar shape, short particles can only be distinguished from PE particles by experienced investigators. By utilizing both imaging and single point mode it was possible to confirm the chemistry of suture even with the presence of narrow peaks.

This study had some limitations. The most prominent drawback was the cut-off of the detectable spectral range below 850 cm−1 due to the intrinsic bandgap of MCT FPA detector, though with more recent advances, current Agilent MCT FPAs have an improved cutoff at ~720cm-1. The limited range in this study did therefore not allow for the accurate direct characterization of metal oxides that were detected and confirmed with EDS. Although this limitation affects some inorganic species, the biological constituents (e.g. cells, proteins) are less concerned. Also, the use of light microscopic images of tissue samples is not ideal for comparison to FTIR chemical images. Light microscopic imaging of H&E stained samples would provide a better context especially with respect to the location of cells. However, this method is only effective if both sample sections (H&E and FTIR-I) were cut consecutively. As histology has been performed at an earlier time point, consecutive samples could not be guaranteed for this study.

In conclusion, FTIR-I provides valuable biochemical information that provides a better understanding of specific wear and corrosion products from joint replacements within the periprosthetic tissue of THR patient. Furthermore, FTIR-I can be employed to detect changes in the biological environment. FTIR-I provides a fast chemical assessment of joint capsule tissue samples which should ideally be coupled with a corresponding sequential H&E slide. The combination of polarized light imaging of H&E stained tissue, EDS, and FTIR-I is an ideal and complementary approach to fully characterize the reaction to implant debris over several square millimeters of tissue. As wear and corrosion are still a major cause of premature implant failure and revision surgery, it is important to advance our knowledge on how wear debris and corrosion products trigger an adverse tissue response.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This study was funded by NIH/NIAMS grant R01 AR070181. The authors would like to thank Dr. Mustafa Kansiz (Agilent Technologies) for valuable comments and suggestions. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Michel Laurent (Rush University Medical Center) for helpful discussion.

References

- 1.Cooper HJ et al. Corrosion at the head-neck taper as a cause for adverse local tissue reactions after total hip arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 94, 1655–1661 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGrory BJ, MacKenzie J & Babikian G A High Prevalence of Corrosion at the Head–Neck Taper with Contemporary Zimmer Non-Cemented Femoral Hip Components. J. Arthroplasty 30, 1265–1268 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingham E & Fisher J The role of macrophages in osteolysis of total joint replacement. Biomaterials 26, 1271–1286 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langton DJ et al. Adverse reaction to metal debris following hip resurfacing: the influence of component type, orientation and volumetric wear. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 93, 164–171 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall DJ et al. Corrosion of Modular Junctions in Femoral and Acetabular Components for Hip Arthroplasty and Its Local and Systemic Effects in Modularity and Tapers in Total Joint Replacement Devices (eds. Greenwald AS, Kurtz SM, Lemons JE & Mihalko WM) 410–427 (ASTM International, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs JJ et al. Local and distant products from modularity. Clin. Orthop. 319, 94–105 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catelas I et al. Effects of digestion protocols on the isolation and characterization of metal–metal wear particles. II. Analysis of ion release and particle composition. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 55, 330–337 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milošev I & Remškar M In vivo production of nanosized metal wear debris formed by tribochemical reaction as confirmed by high-resolution TEM and XPS analyses: In Vivo Production of Nanosized Metal Wear Debris. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 91A, 1100–1110 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia Z et al. Nano-analyses of wear particles from metal-on-metal and non-metal-on-metal dual modular neck hip arthroplasty. Nanomedicine Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 13, 1205–1217 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doorn PF et al. Metal wear particle characterization from metal on metal total hip replacements: Transmission electron microscopy study of periprosthetic tissues and isolated particles. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 42, 103–111 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Catelas I et al. Effects of digestion protocols on the isolation and characterization of metal–metal wear particles. I. Analysis of particle size and shape. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 55, 320–329 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goode AE et al. Chemical speciation of nanoparticles surrounding metal-on-metal hips. Chem. Commun. 48, 8335 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pourzal R, Catelas I, Theissmann R, Kaddick C & Fischer A Characterization of Wear Particles Generated from CoCrMo Alloy under Sliding Wear Conditions. Wear 271, 1658–1666 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart AJ et al. The chemical form of metallic debris in tissues surrounding metal-on-metal hips with unexplained failure. Acta Biomater. 6, 4439–4446 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E & Bozic KJ Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 96, 624–630 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Joint Replacement Registry. Fourth AJJR Annual Report on Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Data. (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Günther K-P et al. Consensus statement ‘Current evidence on the management of metal-on-metal bearings’--April 16, 2012. Hip Int. J. Clin. Exp. Res. Hip Pathol. Ther. 23, 2–5 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine BR et al. Ten-year outcome of serum metal ion levels after primary total hip arthroplasty: a concise follow-up of a previous report*. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 95, 512–518 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moran MM, Wilson BM, Ross RD, Virdi AS & Sumner DR Arthrotomy-based preclinical models of particle-induced osteolysis: A systematic review. J. Orthop. Res. Off. Publ. Orthop. Res. Soc. (2017). doi: 10.1002/jor.23619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fillingham YA et al. Serum Metal Levels for Diagnosis of Adverse Local Tissue Reactions Secondary to Corrosion in Metal-on-Polyethylene Total Hip Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 32, S272–S277 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lohmann C. et al. Periprosthetic Tissue Metal Content but Not Serum Metal Content Predicts the Type of Tissue Response in Failed Small-Diameter Metal-on-Metal Total Hip Arthroplasties: J. Bone Jt. Surg.-Am Vol. 95, 1561–1568 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker MJ et al. Investigating FTIR based histopathology for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. J. Biophotonics 2, 104–113 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bird B et al. Infrared spectral histopathology (SHP): a novel diagnostic tool for the accurate classification of lung cancer. Lab. Invest. 92, 1358–1373 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leslie LS, Kadjacsy-Balla A & Bhargava R High-definition Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic imaging of breast tissue. in 9420, 94200I (International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan KLA, Kazarian SG, Mavraki A & Williams DR Fourier Transform Infrared Imaging of Human Hair with a High Spatial Resolution without the Use of a Synchrotron. Appl. Spectrosc. 59, 149–155 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bassan P et al. Whole organ cross-section chemical imaging using label-free mega-mosaic FTIR microscopy. Analyst 138, 7066–7069 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh MJ et al. FTIR Microspectroscopy Coupled with Two-Class Discrimination Segregates Markers Responsible for Inter- and Intra-Category Variance in Exfoliative Cervical Cytology. Biomark. Insights 3, 179–189 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg JR et al. A multicenter retrieval study of the taper interfaces of modular hip prostheses. Clin. Orthop. 401, 149–161 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall DJ et al. Mechanical, chemical and biological damage modes within head-neck tapers of CoCrMo and Ti6Al4V contemporary hip replacements: DAMAGE MODES IN THR MODULAR JUNCTIONS. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. (2017). doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raju S, Chinnakkannu K, Puttaswamy MK & Phillips MJ Trunnion Corrosion in Metal-on-Polyethylene Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Case Series. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 25, 133–139 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes C, Gaunt L, Brown M, Clarke NW & Gardner P Assessment of paraffin removal from prostate FFPE sections using transmission mode FTIR-FPA imaging. Anal. Methods 6, 1028–1035 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bassan P et al. Resonant Mie scattering (RMieS) correction of infrared spectra from highly scattering biological samples. Analyst 135, 268–277 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lasch P Spectral pre-processing for biomedical vibrational spectroscopy and microspectroscopic imaging. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 117, 100–114 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lasch P, Haensch W, Naumann D & Diem M Imaging of colorectal adenocarcinoma using FT-IR microspectroscopy and cluster analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Basis Dis. 1688, 176–186 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bassan P et al. FTIR microscopy of biological cells and tissue: data analysis using resonant Mie scattering (RMieS) EMSC algorithm. Analyst 137, 1370–1377 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wrobel TP, Kwak JT, Kadjacsy-Balla A & Bhargava R High-definition Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic imaging of prostate tissue. in (eds. Gurcan MN & Madabhushi A) 97911D (2016). doi: 10.1117/12.2217341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonifacio A et al. Chemical imaging of articular cartilage sections with Raman mapping, employing uni- and multi-variate methods for data analysis. The Analyst 135, 3193 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tran TN, Wehrens R & Buydens LMC Clustering multispectral images: a tutorial. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 77, 3–17 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonifacio A, Beleites C & Sergo V Application of R-mode analysis to Raman maps: a different way of looking at vibrational hyperspectral data. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 407, 1089–1095 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belbachir K, Noreen R, Gouspillou G & Petibois C Collagen types analysis and differentiation by FTIR spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 395, 829–837 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Movasaghi Z, Rehman S & Rehman DI ur. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy of Biological Tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 43, 134–179 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collier JP et al. Overview of Polyethylene as a Bearing Material Comparison of Sterilization Methods. Clin. Orthop. 333, 76 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller FA & Wilkins CH Infrared spectra and characteristic frequencies of inorganic ions. Anal. Chem. 24, 1253–1294 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Urban RM, Jacobs JJ, Gilbert JL & Galante JO Migration of corrosion products from modular hip prostheses. Particle microanalysis and histopathological findings. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 76, 1345–1359 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huber M, Reinisch G, Trettenhahn G, Zweymuller K & Lintner F Presence of corrosion products and hypersensitivity-associated reactions in periprosthetic tissue after aseptic loosening of total hip replacements with metal bearing surfaces. Acta Biomater. 5, 172–180 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boskey A & Camacho NP FT-IR Imaging of Native and Tissue-Engineered Bone and Cartilage. Biomaterials 28, 2465–2478 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fowler BO, Moreno EC & Brown WE Infra-red spectra of hydroxyapatite, octacalcium phosphate and pyrolysed octacalcium phosphate. Arch. Oral Biol. 11, 477–492 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenthal AK, Mattson E, Gohr CM & Hirschmugl CJ Characterization of articular calcium-containing crystals by synchrotron FTIR. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 16, 1395–1402 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berzina-Cimdina L & Borodajenko N Research of Calcium Phosphates Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. (2012). doi: 10.5772/36942 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ryu K et al. The prevalence of and factors related to calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition in the knee joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22, 975–979 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skogareva LS, Ivanov VK, Baranchikov AE, Minaeva NA & Tripol’skaya TA Effects caused by glutamic acid and hydrogen peroxide on the morphology of hydroxyapatite, calcium hydrogen phosphate, and calcium pyrophosphate. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 60, 1–8 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chhor K, Bocquet JF & Pommier C Syntheses of submicron TiO2 powders in vapor, liquid and supercritical phases, a comparative study. Mater. Chem. Phys. 32, 249–254 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rabotyagova OS, Cebe P & Kaplan DL Collagen Structural Hierarchy and Susceptibility to Degradation by Ultraviolet Radiation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 28, 1420–1429 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baker MJ et al. Using Fourier transform IR spectroscopy to analyze biological materials. Nat. Protoc. 9, 1771–1791 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Giambattista L et al. New marker of tumor cell death revealed by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 399, 2771–2778 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Endo M et al. Comparison of wear, wear debris and functional biological activity of moderately crosslinked and non-crosslinked polyethylenes in hip prostheses. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. [H] 216, 111–122 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang A, Essner A, Stark C & Dumbleton JH Comparison of the size and morphology of UHMWPE wear debris produced by a hip joint simulator under serum and water lubricated conditions. Biomaterials 17, 865–871 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scott M, Morrison M, Mishra SR & Jani S Particle analysis for the determination of UHMWPE wear. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 73B, 325–337 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Urban RM et al. Characterization of Solid Products of Corrosion Generated by Modular-Head Femoral Stems of Different Designs and Materials. (1997). doi: 10.1520/STP12019S [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Di Laura A et al. The Chemical Form of Metal Species Released from Corroded Taper Junctions of Hip Implants: Synchrotron Analysis of Patient Tissue. Sci. Rep. 7, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urban RM et al. Characterization of Solid Products of Corrosion Generated by Modular-Head Femoral Stems of Different Designs and Materials. (1997). doi: 10.1520/STP12019S [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kung MS et al. Histological Characterization of Chromium Orthophosphate Corrosion Products from Modular Total Hip Replacements in Modularity and Tapers in Total Joint Replacement Devices (eds. Greenwald AS, Kurtz SM, Lemons JE & Mihalko WM) 428–439 (ASTM International, 2015). doi: 10.1520/STP159120140141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Catelas I et al. Effects of digestion protocols on the isolation and characterization of metal–metal wear particles. I. Analysis of particle size and shape. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 55, 320–329 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gill HS, Grammatopoulos G, Adshead S, Tsialogiannis E & Tsiridis E Molecular and immune toxicity of CoCr nanoparticles in MoM hip arthroplasty. Trends Mol. Med. 18, 145–155 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]