Abstract

Typhuloid fungi are a very poorly known group of tiny clavarioid homobasidiomycetes. The phylogenetic position and family classification of the genera targeted here, Ceratellopsis, Macrotyphula, Pterula sensu lato and Typhula, are controversial and based on unresolved phylogenies. Our six-gene phylogeny with an expanded taxon sampling shows that typhuloid fungi evolved at least twice in the Agaricales (Pleurotineae, Clavariineae) and once in the Hymenochaetales. Macrotyphula, Pterulicium and Typhula are nested within the Pleurotineae. The type of Typhula (1818) and Sclerotium (1790), T. phacorrhiza and S. complanatum (synonym T. phacorrhiza), are encompassed in the Macrotyphula clade that is distantly related to a monophyletic group formed by species usually assigned to Typhula. Thus, the correct name for Macrotyphula (1972) and Typhula is Sclerotium and all Typhula species but those in the T. phacorrhiza group need to be transferred to Pistillaria (1821). To avoid undesirable nomenclatural changes, we suggest to conserve Typhula with T. incarnata as type. Clavariaceae is supported as a separate, early diverging lineage within Agaricales, with Hygrophoraceae as a successive sister taxon to the rest of the Agaricales. Ceratellopsis s. auct. is polyphyletic because C. acuminata nests in Clavariaceae and C. sagittiformis in the Hymenochaetales. Ceratellopsis is found to be an earlier name for Pterulicium, because the type, C. queletii, represents Pterulicium gracile (synonym Pterula gracilis), deeply nested in the Pterulicium clade. To avoid re-combining a large number of names in Ceratellopsis we suggest to conserve it with C. acuminata as type. The new genus Bryopistillaria is created to include C. sagittiformis. The families Sarcomyxaceae and Phyllotopsidaceae, and the suborder Clavariineae, are described as new. Six new combinations are proposed and 15 names typified.

Key words: Agaricomycetes, basidioma evolution, Clavariaceae, clavarioid fungi, Pleurotineae, Sclerotium, Typhulaceae

Taxonomic novelties: New suborder: Clavariineae Olariaga, Huhtinen, Læssøe, J.H. Petersen & K. Hansen

New family: Phyllotopsidaceae Locquin ex Olariaga, Huhtinen, Læssøe, J.H. Petersen & K. Hansen; Sarcomyxaceae Olariaga, Huhtinen, Læssøe, J.H. Petersen & K. Hansen

New genus: Bryopistillaria Olariaga, Huhtinen, Læssøe, J.H. Petersen & K. Hansen

New combinations: Bryopistillaria sagittiformis (Pat.) Olariaga, Huhtinen, Læssøe, J.H. Petersen & K. Hansen; Macrotyphula megasperma (Berthier) Olariaga, Huhtinen, Læssøe, J.H. Petersen & K. Hansen; Macrotyphula phacorrhiza (Reichard: Fr.) Olariaga, Huhtinen, Læssøe, J.H. Petersen & K. Hansen; Typhula podocarpi (Crous) Olariaga, Huhtinen, Læssøe, J.H. Petersen & K. Hansen

Typification: Lectotypification: Ceratella ferryi Quél. & Fautrey, Clavaria aculina Quél., Clavaria microscopica Malbr. & Sacc., Pistillaria aciculata Durieu & Lév. ex Sacc., Pistillaria aculeata Pat., Pistillaria acuminata Fuckel, Pistillaria attenuata Syd. & P. Syd., Pistillaria carestiae Ces. in Bres. & Sacc., Pistillaria equiseticola Boud., Pistillaria helenae Pat., Pistillaria juncicola Bourdot & Galzin, Pistillaria queletii Pat., Pistillaria sagittiformis Pat., Sclerotium complanatum Tode, Typhula brunaudii Quél.

Epitypification: Pistillaria acuminata Fuckel, Pistillaria queletii Pat., Pistillaria sagittiformis Pat., Sclerotium complanatum Tode

Introduction

Clavarioid fungi have club- or coral-shaped basidiomata with the hymenium fully exposed and include at least 540 species (Corner, 1950, Kirk et al., 2008). Phylogenetic studies have demonstrated that clavarioid basidiomata have arisen multiple times from ancestors with agaricoid or corticioid basidiomata in several lineages of Basidiomycota (Pine et al., 1999, Dentinger and McLaughlin, 2006), but molecular phylogenies of clavarioid fungi and allied taxa are far from being complete. Clavarioid lineages are known to have evolved in the Agaricales, Cantharellales, Gomphales, Hymenochaetales, Russulales, Thelephorales and Trechisporales among the Agaricomycetes (Pine et al., 1999, Hibbett and Binder, 2002, Hibbett, 2004, Dentinger and McLaughlin, 2006, Birkebak et al., 2013), but fully supported multigene phylogenies are lacking in most cases and details as to how transitions to a clavarioid basidioma type have occurred are vague. A more comprehensive taxon sampling and addition of more molecular markers is still needed in many groups, including clavarioid fungi, to better understand the evolution of basidioma configuration.

In this study, we target a group of clavarioid fungi with tiny basidiomata (Fig. 1A–K), here referred to as “typhuloid” following e.g. Corner, 1950, Petersen, 1974, Petersen et al., 2014, and Olariaga et al. (2016). Corner (1950: 145) characterised typhuloid fungi by their: i) small basidiomata and limited growth, ii) distinct stipe and fertile head, iii) simple hymenium, iv) epiphytic habitat on wood, stems or leaves, rather than being terricolous, v) smooth, white ellipsoid spores, vi) monomitic, generally clamped hyphae, and vii) agglutination of the hyphae on the surface of the stem. Three genera were regarded as typhuloid, Typhula, Pistillaria and Pistillina (Corner 1950), and were separated from pteruloid fungi (Deflexula, Pterula) with a dimitic hyphal system and from Ceratellopsis with highly reduced clavarioid basidiomata with generally sterile apices. Berthier (1976), in his monograph “Typhula and allied genera”, treated typhuloid fungi in a broader sense and considered Ceratellopsis, Macrotyphula, Pterula and Typhula to represent a natural group without proposing any family classification. Hirticlavula elegans, a member of Clavariaceae producing minute, hairy basidiomata, has also been considered somewhat typhuloid (Petersen et al. 2014), and limits between typhuloid fungi and other reduced clavarioid fungi are not always clear. Typhuloid fungi represent one of the most overlooked, poorly known and enigmatic groups of homobasidiomycetes. The family classification of these fungi is uncertain or based on weakly supported phylogenies with a very limited taxon sampling. Macrotyphula and Typhula were previously placed in Clavariadelphaceae (Corner, 1970, Hawksworth et al., 1995), but recent classifications place both genera in Typhulaceae together with Sclerotium (Kirk et al., 2008, Knudsen and Vesterholt, 2012). The family classification of Ceratellopsis is even more controversial. Initially included by Corner (1970) in Clavariadelphaceae, Jülich (1982) accommodated it in Typhulaceae. Hawksworth et al. (1995) and Begerow et al. (2018), probably following Corner, included it in Gomphaceae, although Ceratellopsis lacks the synapomorphic characters of this family, such as pistillarin, ampullate septa and cyanophilous, ornamented spores (Hosaka et al. 2006). As no molecular data of Ceratellopsis has been available, its phylogenetic relationships and classification have remained doubtful. Besides the above-mentioned genera treated by Berthier (1976), Mucronella and Hirticlavula, both producing tiny clavarioid basidiomata, have been assigned to the Clavariaceae based on molecular data (Birkebak et al., 2013, Petersen et al., 2014). Regardless of their phylogenetic origin, all typhuloid fungi share similar taxonomic problems. For many species of those genera only the type specimen or very few collections are known, species limits are unclear and distribution data are meagre. Molecular data of only a handful of species are available in public sequence repositories and the high morphological diversity of the group remains poorly sampled.

Fig. 1.

Diversity of typhuloid and pleurotoid fungi suggested to be closely related to Typhula. A.Macrotyphula fistulosa s.l. (IO.14.214, ARAN-Fungi). B.Macrotyphula juncea (IO.16.53, S). C.Typhula phacorrhiza, current type of Typhula (ARAN-Fungi 7446), here combined in Macrotyphula. D. Compressed sclerotium of T. phacorrhiza (ARAN-Fungi 7446). E.Typhula incarnata, showing sclerotia at the base (IO.14.92, S), proposed conserved type of Typhula. F.Typhula uncialis (IO.14.94, S, UPS), type of Gliocoryne. G.Typhula crassipes (IO.14.83, S, UPS). H.Typhula subhyalina (IO.15.06, S), type of Pistillina and Dacryopsella. I.Typhula erythropus (IO.16.83, ARAN-Fungi). J.Ceratellopsis aff. aculeata (ARAN-Fungi 11746). K.Pterulicium gracile (IO.14.142, S, UPS). L.Phyllotopsis nidulans (ARAN-Fungi). M.Pleurocybella porrigens (BIO-Fungi 13431). N.Sarcomyxa serotina (IO.14.130, S, UPS). Photographs I. Olariaga, except L by J.I. Iturrioz.

Typhula and segregated genera, Macrotyphula, and phylogenetic position of Typhulaceae

The phylogenetic position of Typhulaceae has been inferred from only two species, Typhula phacorrhiza and Macrotyphula fistulosa, type of Typhula and Macrotyphula, respectively. Through analyses of a 5-locus dataset, Matheny et al. (2006) recovered Typhulaceae in the hygrophoroid clade (Agaricales) with phylogenetic confidence, as sister to the Hygrophoraceae in a supported clade encompassing Pterulaceae and members of two pleurotoid agaric genera (Sarcomyxa serotina and Phyllotopsis spp.) (Fig. 1L–N). Binder et al. (2010), employing a broader taxon sampling of the Agaricomycetes, recovered also Typhulaceae as sister to Hygrophoraceae but without support, while Pterulaceae was supported as closely related to Stephanosporaceae instead (Binder et al. 2010). Other studies have not been able to confirm or reject the inclusion of Typhulaceae in the hygrophoroid clade, but recovered agaric or pleurotoid genera, such as Phyllotopsis, Pleurocybella, Tricholomopsis, as sister taxa of Typhulaceae with phylogenetic confidence (Dentinger and McLaughlin, 2006, Lodge et al., 2014). Dentinger et al. (2016) resolved for the first time several deep nodes of the Agaricales through a 208-locus dataset containing 35 taxa of Agaricales, and found that the hygrophoroid clade, as defined by Matheny et al. (2006), was paraphyletic. Also, Hygrocybe conica (Hygrophoraceae) was recovered as sister to the Clavariaceae, while Pterulaceae (Pterula multifida; recovered in the hygrophoroid clade by Matheny et al. (2006)), appeared in a branch with Pleurotus ostreatus. Thus, the results by Dentinger et al. (2016) question the inclusion of the Typhulaceae in the hygrophoroid clade. In addition to its uncertain phylogenetic position, the monophyly of Typhulaceae has not been tested appropriately.

Two genera, Typhula and Macrotyphula, are currently accepted in Typhulaceae (e.g. Berthier, 1976, Knudsen and Vesterholt, 2012). Macrotyphula differs from Typhula in having large, yellow-brown basidiomata (30–300 mm) that never arise from sclerotia and non-amyloid spores (Berthier 1976). In contrast, Typhula includes species with smaller basidiomata (generally under 10 mm long) that often arise from sclerotia and usually have amyloid spores. Some Typhula species are important plant pathogens that cause economic loss in cereal crops (e.g. Ekstrand 1955). These are popularly known as “snow moulds”, producing symptoms known as “Typhula blight” (Matsumoto et al., 2001, Hoshino et al., 2008). Several economically important species like T. incarnata and T. ishikariensis have been subjected to extensive research on their ecology, physiology and genetics (e.g. Matsumoto, 1992, Vergara et al., 2004, Blunt et al., 2015, Chang, 2015, Koch, 2016). Generic limits of Typhula are not fully delineated and lack a complete consensus. Probably due to the fact that its species show diverse basidioma morphologies, sclerotial anatomy and asexual morph states (Berthier 1976), a number of genera have been segregated from Typhula, such as Cnazonaria, Dacryopsella, Gliocoryne, Phacorhiza, Pistillaria, Pistillina, Scleromitra and Sphaerula. These genera have been used to a certain extent. Of these, Corner (1950) recognised Pistillaria (with Cnazonaria, Gliocoryne, Scleromitra and Sphaerula in synonymy), Pistillina and Typhula (with Phacorhiza in synonymy). Donk (1954) adopted also Pistillaria, Typhula and Pistillina, and further synonymised Dacryopsella under Pistillina. Pistillaria has been recognised generally based on a ceraceous consistency of the fresh fruitbodies, horny when dried, and the absence of sclerotia (Corner, 1950, Corner, 1970, Pilát, 1958), but generic limits between Pistillaria and Typhula have been long debated (Corner, 1950, Bourdot and Galzin, 1928, Donk, 1954, Berthier, 1976). Pistillina has been distinguished by basidiomata with a globose fertile part (Corner 1950). Berthier (1976), after examining extensive material and type specimens available, merged all these genera under Typhula (Sphaerula, Scleromitra and Dacryopsella were not treated in the monograph), but recognised Cnazonaria, Gliocoryne, Pistillaria and Pistillina as subgenera. After the publication of Berthier's monograph, a few authors have continued to use Pistillaria and Pistillina at the generic level (Shiryaev and Kotiranta, 2007, Kaygusuz and Çolak, 2017, Begerow et al., 2018, Petersen and Læssøe, 2019). Recently, the new monotypic genus Tygervalleyomyces was described in Typhulaceae based on analyses of the 28S region (Crous et al. 2017). The asexual morph of Tygervalleyomyces podocarpi, the only known morph, is similar to the asexual morph of Typhula crassipes (Berthier 1976, as Typhula corallina) in the cylindrical conidia with a truncate base, and in fact these two species have highly similar 28S sequences (98 %) and nested within a larger highly supported clade containing other Typhula species (Crous et al. 2017). In view of this, the status of Tygervalleyomyces needs to be re-evaluated in the light of a phylogeny with a broader sampling of Typhula species. Olariaga & Salcedo (2013) synonymised Typhula and Macrotyphula due to the fact that T. phacorrhiza formed a monophyletic group with Macrotyphula in previous analyses (Pine et al., 1999, Hibbett, 2007), as well as morphological similarities. The designation of T. phacorrhiza as lectotype of Typhula by Donk (1933) has been considered unfortunate (Berthier, 1976, Olariaga, 2009, Olariaga and Salcedo, 2013), because T. phacorrhiza, with long filiform basidiomata and unique compressed sclerotia, is an atypical species in Typhula (Remsberg, 1940, Corner, 1950, Berthier, 1976). In fact, T. phacorrhiza shares many features with M. fistulosa, i.e. the pale brown, large basidiomata, the stipe surface with thin hyphae and caulotrichomes, the basal tomentum formed by thick-walled, scarcely septate hyphae and the presence of a hyaline, striped encrustation on the medulla hyphae (Olariaga & Salcedo 2013). Molecular phylogenetic analyses show that these species are closely related and nested in the Agaricales (Binder et al. 2010). Nevertheless, taxon sampling in phylogenetic studies of Typhulaceae is extremely poor and the synonymy of Typhula and Macrotyphula needs to be further explored.

The type of Sclerotium is conspecific with the type of Typhula

The genus Sclerotium, also included in Typhulaceae (Kirk et al. 2008), is currently treated as an artificial genus that accommodates fungi producing sclerotia but not, or rarely, a sexual morph (Xu et al. 2010). Tode (1790) included originally eight species in Sclerotium, of which Fries (1821) treated S. complanatum in the first place and Clements & Shear (1931: 411) thus selected this species as the type of Sclerotium. A number of authors, especially during the XIXth century, described numerous species in Sclerotium, including ascomycetous and basidiomycetous fungi (e.g. Fries, 1822, Léveillé, 1843, Duby, 1830, Desmaziéres, 1848, Rostrup, 1866), and numerous plant pathogens (Xu et al. 2010). Until now, 464 names have been described or combined in Sclerotium (Index Fungorum, viewed on 11 June 2019) and it is evident that species assigned to Sclerotium have multiple evolutionary origins, but very few attempts to disassemble it have been made (Xu et al. 2010). With the end of the asexual-sexual morph dual nomenclature, many names in Sclerotium may turn out to have priority over species names in use. Several early authors observed that some Sclerotium species appeared in connection or directly attached to basidiomata of Typhula species (e.g. Berkeley, 1837, Léveillé, 1843 (as Clavaria), Rostrup 1866). Sclerotium complanatum, type of Sclerotium, is characterised by producing compressed sclerotia attached to the substrate by a small stalk (Tode 1790) which conform to those produced by T. phacorrhiza (Berkeley, 1837, Rostrup, 1866, Schröter, 1889). Thus, it is generally accepted that S. complanatum is a synonym of T. phacorrhiza (Xu et al., 2010, Kaygusuz and Çolak, 2017), although only Remsberg (1940) has proposed this synonymy according to our search. Other authors attributed S. complanatum to the sclerotial morph of T. gyrans (Fries, 1874, Corner, 1950, Donk, 1962), but this view appears to have been abandoned. In the meantime, the taxonomic identity of S. complanatum has not been reassessed and the name remains untypified. As currently asexual names compete with sexual names for priority, the possible synonymy of S. complanatum and T. phacorrhiza would make Sclerotium and Typhula taxonomic synonyms, and all Typhula names in use, including those being applied to economically important plant pathogens, would have to be transferred to the older and equally sanctioned genus Sclerotium. Examining in depth the taxonomic concept of S. complanatum and proposing a typification is thus of paramount importance to deal with a possible scenario of undesirable nomenclatural changes.

The poorly known genus Ceratellopsis, a possible earlier synonym of Pterulicium

Ceratellopsis differs from Typhula in having minute filiform basidiomata with a sterile apex and a non-corticate stipe (Corner, 1950, Berthier, 1976). Short basidia up to 20 μm have also been suggested to be a diagnostic character (Jülich 1982). Pterulicium gracile, called Pterula gracilis until very recently (Leal-Dutra et al. 2020), strongly resembles species of Ceratellopsis because of its minute white basidiomata with a sterile apex, at least at early stages of development (Corner, 1950, Berthier, 1976), but it differs microscopically in having skeletal hyphae, typical for Pterulaceae, 2-spored basidia and no stipe (Corner, 1950, Olariaga, 2009). Furthermore, we have made collections with very minute basidiomata with a clearly delimited stipe suggesting Ceratellopsis, but having skeletal hyphae as typical in Pterulaceae. Limits between Ceratellopsis and Pterulaceae, thus, are not always clear-cut.

As pointed out by Donk, 1954, Konrad and Maublanc, 1937 introduced Ceratellopsis based on the validly published but illegitimate Ceratella Pat. (Patouillard 1887; later homonym of Ceratella Hook. f. 1844) and explicitly indicated Ceratellopsis queletii as the type of Ceratellopsis. While Donk (1954) followed this typification, Corner (1950), noted that C. queletii might represent a rudimentary Pterula, and he selected instead Ceratellopsis aculeata as type so that Ceratellopsis could be used with certainty and not reduced to a synonym of Pterula. This choice, nevertheless, is not permissible (Turland et al. 2018; Art. 7.8) since the original type indication of Ceratellopsis by Konrad & Maublanc (1937) is unequivocal and irrevocable. Also, Olariaga (2009) proposed tentatively that C. queletii might be a synonym of Pterulicium gracile, but up to present, no consistent and stable interpretation of C. queletii has been provided and the taxonomic status of Ceratellopsis remains unresolved. Twenty-four names have been described or combined in Ceratellopsis, but several of them represent P. gracile (Berthier 1976) or Typhula species.

The confirmation that C. queletii, type of Ceratellopsis, is a synonym of P. gracile would have important consequences in the classification of Pterulaceae. The family, centered on the genus Pterula, has included several clavarioid genera with a dimitic hyphal system (Corner 1970). Based on molecular studies, four resupinate genera (Aphanobasidium, Coronicium, Merulicium, Radulomyces; Larsson, 2007, Larsson et al., 2004) and the polyporoid Radulotubus (Zhao et al. 2016) were later transferred to Pterulaceae. In the light of analyses of the ITS, 28S and RPB2 regions, employing a rich taxon sampling of the Pterulaceae, Leal-Dutra et al. (2020) elucidated generic limits in the family. This study discovered Pterula to be polyphyletic and splits its species into the new genus Myrmepterula, Phaeopterula and Pterulicium, leaving in Pterula sensu stricto a handful of species around Pterula plumosa. Deflexula was shown to be paraphyletic because some species nest in the Pterula clade, while the type D. fascicularis is in the Pterulicium clade. In total, 46 names earlier treated in Pterula and Deflexula were combined in Pterulicium, a genus up to then monospecific. Pterula gracilis was found to belong to the Pterulicium clade and accordingly combined as Pterulicium gracile. In this framework, would the synonymy between C. queletiti and P. gracile be confirmed, the name Ceratellopsis (1937) would have priority over Pterulicium (1950). Thus, the identity of C. queletii needs urgent clarification.

In the present study, we expand the taxon sampling of typhuloid fungi based on the multigene datasets used by Matheny et al. (2006) and Binder et al. (2010). With these data, our main goals were to: 1) provide a robust phylogenetic hypothesis for typhuloid fungi, especially for T. phacorrhiza (type of Typhula), types of genera segregated from Typhula, Sclerotium complanatum (type of Sclerotium) and Ceratellopsis species; 2) test the monophyly of Typhula; 3) assign typhuloid fungi to appropriate families; and 4) propose an updated nomenclature in the light of a robust multigene phylogeny.

Material and methods

Molecular techniques

DNA was extracted from fresh (stored in 1 % SDS extraction buffer) basidiomata, using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following six gene regions were amplified: 1) nu5.8S rDNA, the 5′ end of the nuclear 28S rDNA (spanning domains D1–D2), part of the nuSSU rDNA (ca. 1 600 bp), RPB1 (900 bp; A–C), RPB2 (5–7 region, ca. 1 100 bp) and EF-1α (1 100 bp). The ITS (ITS1-5.8S-ITS2) and 28S regions were amplified in one piece using the primers ITS5-LR7, or otherwise as separate pieces: ITS using ITS5-ITS4, (White et al. 1990); and 28S using LR0R-LR5 (or LR3) and LR3R-LR7 (Vilgalys & Hester 1990). The same primers were used for sequencing. The ITS was sequenced using the primers ITS1-ITS4 and/or in a few instances ITS5, 5.8S and ITS3. The SSU region was amplified in one piece employing primers NS1-NS8 or in two pieces using NS1-NS4 and NS3-NS8 (White et al. 1990). PCR products of the RPB1 region were obtained using gRPB1-A (Stiller & Hall 1997) and fRPB1-C rev primers (Matheny et al. 2002). The sequence spanning RPB2 regions 5–7 was amplified in one piece, using fRPB2-5F and bRPB2-7R, or if required, in two pieces with primers fRPB2-5F-gRPB2-6R and bRPB2-6F-bRPB2-7R (Liu et al., 1999, Matheny, 2005). For samples that did not succesfully amplify or for sequencing, Typhula-specific primers were designed for the RPB2 region and used in different combinations (Table 1). The EF-1α region was PCR amplified and sequenced employing 983F and 2218R primers (Rehner & Buckley 2005). Typhula-specific primers of the EF-1α region were designed and used for PCR amplification and sequencing of problematic samples (Table 1). PCR amplifications were performed using Illustra™ Hot Start Mix RTG PCR beads (GE Healthcare, UK) in a 25 μL volume, containing 3 μL of genomic DNA, 10 μM of each primer and distilled water. PCRs were conducted in Applied Biosystems GeneAmp® PCR System 9700 and 2720 Thermal Cyclers. Amplifications were performed using the following program: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35–40 cycles of 95 °C for 45–60 s, 52–58 °C for 50 s, 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR amplifications of protein-coding genes follow O’Donnell et al. (2011, RPB1) and Hansen et al. (2013, RPB2, EF-1α). PCR products were purified using the enzymatic method Exo-sap-IT (USB Corporation, Santa Clara, California, USA). When multiple bands were amplified in the RPB1 and RPB2 regions, PCR products were size-fractionated in a 1 % agarose gel, stained with GelRed™ (Biotium Inc.), visualised over a UV trans-illuminator, excised and purified using QIAquick spin columns (Qiagen). Purified PCR products were sequenced at Macrogen Europe service (www.macrogen.com).

Table 1.

Newly designed Typhula-specific primers for the RPB2 and EF-1α (5’–3’) regions.

| Locus | Primer | Sequence | PCR | Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF-1α | 1007F-Typh | SCGAGGAYCGTTTCAACGAG | X | |

| EF-1α | 1447F-Typh | GCATGCCHTGGTWCAAGG | X | X |

| EF-1α | 1825F-Typh | GAACGTVTCCGTYAAGGAYA | X | |

| EF-1α | 2100R-Typh | ATKGGCTTGGARGGRACRA | X | |

| RPB2 | RPB2-5Fint-Typh | AARAARCGDYTNGAYYTSGC | X | |

| RPB2 | RPB2-6F-Typh | TGGGGAYTGGAGTCGTTGGA | X | X |

| RPB2 | RPB2-6R-Typh | TCCAACGACTCCARTCCCCA | X | X |

| RPB2 | RPB2-7Rint-Typh | TASGTGTTACGAGGRGACT | X |

Type specimens, taxon and molecular sampling

Type specimens of small typhuloid fungi available at E, FH, M, PC, S and UPS herbaria were examined: Ceratella ferryi, Ceratellopsis carestiae, C. rickii, C. acuminata, C. equiseticola, Clavaria aculina, C. microscopica, Pistillaria attenuata, P. juncicola, Pterulicium gracile, Typhula brunaudii, T. crassipes, T. sclerotioides, T. sphaeroidea, T. subhyalina and T. uncialis. Material deposited in G (customs blocked the loan), PAD (not available on loan) and SAPA (several contact attempts unsuccessful) could not be examined. The notation “!” indicates that type or other original material was examined by us. Cultures of the taxa collected and described in this study were deposited in the CBS-KNAW culture collection at the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute.

For molecular analyses, types and other species of genera considered to be typhuloid or assigned to Typhulaceae were sampled, namely Ceratellopsis, Macrotyphula, Pterulicium gracile, Typhula s.l. and Sclerotium. A collection identified as C. acuminata, with skeletal hyphae, was included to test the limits between Ceratellopsis and Pterula. Nucleotide sequences were aligned in the six-gene dataset (nu5.8S rDNA, nu28S rDNA, nu18S rDNA, RPB1, RPB2 and EF-1α) assembled by Binder et al. (2010; TreeBASE no. S10185), in order to preliminarily explore their phylogenetic affinities. Nucleotide sequences were aligned in Aliview (Larsson 2014). This alignment was subjected to a maximum likelihood (ML) analysis using the “RAxML HPC2 on XSEDE” tool (Stamatakis 2014) in the CIPRES Science Gateway (Miller et al. 2010), starting from a random tree. A GTR-GAMMA model with four rate categories was selected for tree inference. For branch confidence, 1 000 ML bootstrap replicates were conducted with a GTRCAT model (ML-BP). Targeted typhuloid taxa nested in Agaricales (ML-BP 92 %), except for Ceratellopsis sagittiformis that was placed in Hymenochaetales. Based on this analysis, a first 6-locus (5.8S, 28S, 18S, RPB1, RPB2, EF-1α) dataset (the Agaricales matrix) was prepared to phylogenetically place typhuloid fungi among the Agaricales. Three taxa, Amylocorticium cebennense, Plicaturopsis crispa and Serpulomyces borealis, were included as outgroup for rooting purposes based on previous studies (Binder et al. 2010). A second dataset with the same molecular markers (the Pleurotineae matrix) included Typhulaceae and closely related families, with a more species-inclusive sampling than in the Agaricales matrix. Cantharocybe gruberi was used as an outgroup based on analyses of the Agaricales matrix. A third 28S alignment (the Clavariaceae matrix) was constructed based on Birkebak et al. (2013) to infer phylogenetic relationships of Ceratellopsis within the Clavariaceae, and employed Anomoporia bombycina, A. kamtschatica and Podoserpula pusio as outgroup taxa. A fourth 4-locus (5.8S, 28S, 18S, RPB2) dataset (the Hymenochaetales matrix) was assembled to further explore phylogenetic relationships of C. sagittiformis within the Hymenochaetales. Sequences of Calocera cornea were set as outgroup.

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analyses

Sequences were edited and assembled using Sequencher v. 4.10.1 (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI) and deposited in GenBank (Table 2). Additional sequences were downloaded from GenBank and from the following genomes through the MycoCosm portal (Grigoriev et al. 2014): Agaricus bisporus, Coprinopsis cinerea (Muraguchi et al. 2015), Laccaria bicolor (Martin et al. 2008), Onnia scaura, Phellinus ferrugineofuscus, Plicaturopsis crispa (Kohler et al. 2015), Pterulicium gracile (Varga et al. 2019, deposited as Pterula gracilis), Radulomyces confluens and Trichaptum abietinum (Table 2). Nucleotide sequences were aligned manually using Aliview (Larsson 2014). Protein-coding genes were translated to amino acids to determine intron positions. In order to check gene-tree congruence, each individual gene-region was analysed using a ML approach, as explained above. Gene congruence was assessed manually by comparing supported clades among single-gene genealogies (Mason-Gamer & Kellogg 1996). Clades were considered in conflict if a supported clade (ML-BP >70 %) for one marker was contradicted with significant support by another one. Since no conflict was detected, markers were concatenated in the Agaricales, Typhulaceae and Hymenochaetales alignments. Introns were excluded and the third codon position was partitioned in the protein-coding genes (RPB1, RPB2 and EF-1α). Each matrix was subjected to ML and Bayesian analyses. ML analyses were conducted as explained above. Bayesian analyses were implemented in MrBayes v. 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al. 2012), using two parallel runs of eight Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMCMC) chains for 30 M generations, starting from a random tree, and sampling one tree every 1 000th generation from the posterior distribution. Substitution models were sampled across the GTR space during the MCMC simulation (Ronquist et al. 2012). Stationarity was assumed when average standard deviation of split frequencies fell below 0.01. A burn-in sample of 30 000 trees was discarded. To assess branch confidence, a 50 % majority rule consensus tree was computed with the remaining 30 002 trees using the SUMT command of MrBayes. Bayesian posterior probability (PP) values ≥0.95 were considered to be significant. The alignments and respective phylogenetic trees were deposited in TreeBASE, study number S25967.

Table 2.

Sequenced specimens used in this study, with GenBank accession numbers for 5.8S, 28S, 18S, RPB1, RPB2 and EF-1α regions. Numbers in parentheses following the species names indicate multiple collections of a species. The GenBank accessions of sequences generated in this study are in bold. Asterisks indicate sequences obtained from genome data through the JGI portal (https://jgi.doe.gov/). Abbreviations of datasets are: ag = Agaricales, cl = Clavariineae; hy = Hymenochaetales, pl = Pleurotineae.

| Original name | Updated name | Voucher specimen | Dataset | GenBank accession numbers |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.8S | 28S | 18S | RPB1 | RPB2 | EF-1α | ||||

| Agaricus bisporus∗ | — | H97 | ag | Genome | Genome | Genome | genome | Genome | genome |

| Alloclavaria purpurea | — | PBM 2731 (CUW) | hy | DQ486690 | DQ457657 | DQ437679 | — | — | — |

| Anomoporia bombycina | — | CFMR:L-6240 | cl | — | GU187564 | — | — | — | — |

| A. kamtschatica | — | GB/M Edman K426 | cl | — | DQ144615 | — | — | — | — |

| Anthracophyllum archeri | — | PBM 2201 (WTU) | ag | DQ444308 | AY745709 | DQ092915 | DQ435799 | DQ385877 | DQ028586 |

| Amanita brunnescens | — | PBM 2429 (CUW) | ag | AY789079 | AY631902 | AY707096 | AY788847 | AY780936 | AY881021 |

| Aphanobasidium pseudotsugae | — | HHB-822 (CFMR) | ag, pl | GU187509 | GU187567 | GU187620 | GU187695 | GU187781 | GU187695 |

| Armillaria mellea | — | PBM 2470 (CUW) | ag | AY789081 | AY700194 | AY787217 | AY788849 | AY780938 | AY881023 |

| Baeospora myosura | — | PBM 2748 (CUW) | ag | DQ484063 | DQ457648 | DQ435796 | DQ435801 | DQ470827 | GU187762 |

| Basidioradulum radula | — | GEL 2493 (KASSEL) | hy | DQ234537 | AY700184 | AY771611 | — | — | — |

| Blasiphalia pseudogrisella | — | P. Hoijer 4393 (H7031951)/ IO.14.231 (S) | hy | MF319048 | MF318899 | MF318990 | — | MT24239 | — |

| Bolbitius vitellinus | — | MTS 5020 (WTU) | ag | DQ200920 | AY691807 | AY705955 | DQ435802 | DQ385878 | DQ408148 |

| Camarophyllopsis schulzeri | — | S. Jacobsson 3453 (H) | cl | — | AM946415 | — | — | — | — |

| Cantharellopsis prescotii | — | I. Kytovuori 08-0808/ H6059300 | hy | MF319050 | MF318901 | MF318992 | — | MF288855 | — |

| Cantharocybe gruberi | — | PBM 510 (WTU) | ag, pl | DQ200927 | DQ234540 | DQ234546 | DQ435808 | DQ385879 | DQ059045 |

| Ceratellopsis acuminatea | — | CBS 146691 | ag, cl | MT232347 | MT232298 | MT232493 | MT24236 | MT24230 | MT242352 |

| C. aculeatea | — | ARAN-Fungi 13729 | cl | — | MT232300 | — | — | — | — |

| C. aff. acuminatea | — | ARAN-Fungi 11746 | cl | MT232348 | MT232299 | — | — | — | — |

| C. sagittiformis(1) | Bryopistillaria sagittiformis | IO.15.41 (S) | hy | — | MT232301 | — | — | MT24231 | — |

| C. sagittiformis(2) | B. sagittiformis | IO.15.85 (S) | hy | — | MT232302 | — | — | MT24232 | — |

| C. sagittiformis(3) | B. sagittiformis | IO.14.164 (S) | hy | MT232349 | MT232303 | — | — | MT24233 | — |

| Cheimonophyllum candidissimum | — | PBM 2411 (WTU) | ag | DQ486687 | DQ457654 | DQ435812 | DQ447888 | DQ470831 | GU187760 |

| Calocera cornea | — | GEL 5359 (KASSEL) | hy | AY789083 | AY701526 | AY771610 | — | AY536286 | — |

| Clavaria acuta(1) | — | RHP55840 (TENN043602) | cl | — | HQ877681 | — | — | — | — |

| C. acuta(2) | — | MTS4577 (WTU) | cl | — | HQ877679 | — | — | — | — |

| C. acuta(3) | — | JFA10440 (WTU) | cl | — | HQ877680 | — | — | — | — |

| C. alboglobospora | — | TENN042295 | cl | — | HQ877682 | — | — | — | — |

| C. argillacea | — | TFB10720 (TENN058804) | cl | — | HQ877683 | — | — | — | — |

| C. australiana | — | ADM1311 (TENN051311) | cl | — | HQ877685 | — | — | — | — |

| C. aff. fragilis | — | SAT98-349-01 (WTU) | cl | — | HQ877688 | — | — | — | — |

| C. fumosa | — | GG_151003 | cl | — | EF535268 | — | — | — | — |

| C. fuscata | — | RHP55840 (TENN043602) | cl | — | HQ877681 | — | — | — | — |

| C. inaequalis | — | MB 04-016 (WTU) | cl | — | AY745693 | — | — | — | — |

| C. pullei | — | KGN98 | cl | — | AY586646 | — | — | — | — |

| C. cf. rubicundula | — | TENN043695 | cl | — | HQ877697 | — | — | — | — |

| Clavaria sp.(1) | — | TFB11835 (TENN060720) | cl | — | HQ877692 | — | — | — | — |

| Clavaria sp.(2) | — | JMB10061001 (TENN065665) | cl | — | HQ877684 | — | — | — | — |

| C. stegasauroides | — | PBM3373 | cl | — | HQ877698 | — | — | — | — |

| C. zollingeri | — | JMB08040912 (TENN064095) | cl | — | HQ877700 | — | — | — | — |

| Clavicorona taxophila | — | 9186 | cl | — | AF115333 | — | — | — | — |

| Clavulinopsis amoena | — | PBM3381 | cl | — | HQ877702 | — | — | — | — |

| C. corallinorosacea | — | PBM3380 | cl | — | HQ877707 | — | — | — | — |

| C. fusiformis | — | MGW672 (TENN064110) | cl | — | HQ877717 | — | — | — | — |

| C. sulcata | — | PBM3379 | cl | — | HQ877709 | — | — | — | — |

| Clitocella mundula | — | TJB 7599 (CORT) | ag | DQ494694 | AY700182 | DQ089017 | DQ447937 | DQ474128 | — |

| C. candicans | — | WTU | ag | DQ202268 | AY645055 | AY771609 | DQ447891 | DQ385881 | DQ408149 |

| C. subditopoda | — | WTU | ag | DQ202269 | AY691889 | AY771608 | DQ447892 | AY780942 | DQ408150 |

| Coltricia perennis | — | P. Salo 11024 (H) | hy | MF319056 | MF318907 | MF318996 | — | MF288856 | — |

| Collybia tuberosa | — | TENN 53540 | ag | AY854072 | AY639884 | AY771606 | AY857982 | AY787219 | AY881025 |

| Conocybe lactea | — | PBM 2411 (WTU) | ag | DQ486693 | DQ457660 | DQ437683 | DQ447893 | DQ470834 | — |

| Coprinus comatus | — | ECV 3198 (UC) | ag | AY854066 | AY635772 | AY665772 | AY857983 | AY780934 | AY881026 |

| Coprinopsis cinerea∗ | — | AmutBmut #326 | ag | genome | Genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| Coronicium alboglaucum | — | NH4208 | pl | AY463400 | AY586650 | — | — | — | — |

| Cortinarius iodes | — | WTU | ag | AF389133 | AY702013 | AY771605 | AY857984 | AY536285 | AY881027 |

| Cotylidia sp. | — | WTU | hy | AY854079 | AY629317 | AY705958 | — | AY883422 | — |

| C. undulatea | — | IO.15.126 (S) | hy | MT232350 | MT232304 | — | — | MT24234 | — |

| Crepidotus cf. applanatus | — | PBM 717 (WTU) | ag | DQ202273 | AY380406 | AY705951 | AY333303 | AY333311 | DQ028581 |

| Cristinia sp. | — | FP-100305 (CFMR) | pl | GU187526 | GU187585 | GU187637 | GU187470 | GU187793 | GU187718 |

| Entoloma prunuloides | — | TJB 4765 (CORT) | ag | DQ206983 | AY700180 | AY665784 | DQ447898 | DQ385883 | DQ457633 |

| Globulicium hiemale | — | Hjm 19007 (GB) | hy | DQ873595 | DQ873595 | DQ873594 | — | — | — |

| Gymnopus contrarius | — | PBM 2711 (WTU) | ag | DQ486708 | DQ457670 | DQ440643 | DQ447902 | DQ472716 | GU187700 |

| Gyroflexus brevibasidiata | — | IO.14.230 (S) | hy | MT232351 | MT232305 | — | — | MT24235 | — |

| Fibricium rude | GEL 2121 (KASSEL) | hy | — | AY700202 | AY654888 | — | — | — | |

| Fistulina Antarctica | — | — (AFTOL-ID 1335) | ag | DQ486702 | AY293181 | AY293131 | DQ447899 | DQ472713 | GU187698 |

| Flammulina velutipes | — | TENN 52002 | ag | AY854073 | AY639883 | AY665781 | AY858966 | AY786055 | AY883423 |

| Hemimycena gracilis | — | PBM 2715 (WTU) | ag | DQ490623 | DQ457671 | DQ440644 | DQ447905 | DQ472719 | GU187709 |

| Hirticlavula elegans | — | JHP-13.364 (O) | cl | — | KJ939349 | — | — | — | — |

| Hodophilus aff. foetens | — | ECV4175 (TENN065670) | cl | — | HQ877678 | — | — | — | — |

| Hodophilus hymenocephalus(1) | — | WTU | cl | — | DQ457679 | — | — | — | — |

| H. hymenocephalus(2) | — | DJL98_081505 | cl | — | EF561628 | — | — | — | — |

| Hohenbuehelia tremula | — | PBM 2301 (WTU)/ DAOM 180808 | pl | DQ182504 | KU355405 | DQ440645 | — | KU355434 | KU355465 |

| Hydropus cf. scabripes | — | WTU | ag | DQ404389 | DQ411536 | DQ444855 | DQ447908 | DQ457634 | — |

| Hygrocybe coccinea | — | PBM 915 (WTU) | ag, cl | DQ490629 | DQ457676 | DQ444858 | DQ447910 | DQ472723 | GU187705 |

| H. aff. conica | — | CBS 300.56 | cl | — | DQ534589 | — | — | — | — |

| Hygrophorus pudorinus | — | PBM 2721 (WTU) | ag | DQ490631 | DQ457678 | DQ444861 | DQ447912 | DQ472725 | GU187710 |

| Hyphodontia alutaria | — | KHL 11889 (GB) | hy | DQ873603 | DQ873603 | DQ873602 | — | — | — |

| Hyphodontiella multiseptata | — | Ryberg 021022 (GB) | cl | — | EU118634 | — | — | — | — |

| Inocybe myriadophylla | — | JV 19652F (WTU) | ag | DQ221106 | AY700196 | AY657016 | DQ447916 | AY803751 | DQ435791 |

| Inonotus griseus | — | Dai 13436 | hy | KX674583 | KX364823 | — | — | KX364919 | — |

| Infundibulicybe gibba | — | JCS 0704B (WTU) | ag | DQ490635 | DQ457682 | DQ115780 | DQ447913 | DQ472727 | GU187759 |

| Kneiffiella subalutacea | — | KHL 11888 (GB) | hy | DQ873630 | DQ873631 | DQ873629 | — | — | — |

| Kuehneromyces rostratus | — | PBM 2703 (WTU) | ag | DQ490638 | DQ457684 | DQ457624 | DQ447918 | DQ472730 | GU187712 |

| Laccaria bicolor∗ | — | S238N | ag | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| Lachnella villosa | — | CBS 609.87 | ag | DQ097362 | DQ097347 | AY705959 | — | DQ472732 | GU187721 |

| Leifia flabelliradiata | — | KG Nilsson 36270 (GB) | hy | DQ873635 | DQ873635 | — | — | — | — |

| Lepista irina | — | PBM 2291 (WTU) | ag | DQ221109 | DQ234538 | AY705948 | DQ447919 | DQ385885 | DQ028591 |

| Lycoperdon pyriforme | — | DSH 96-054 (WTU) | ag | AY854075 | AF287873 | AF026619 | AY860523 | AY218495 | AY883426 |

| Macrolepiota dolichaula | — | HKAS | ag | DQ221111 | DQ411537 | AY771602 | DQ447920 | DQ385886 | DQ435785 |

| Macrotyphula fistulosa(1) | — | IO.14.219 (S)/ IO.15.123 (ARAN-Fungi, S)/ TUB 011469 | ag | — | DQ071735 | MT232494 | DQ068002 | MT24236 | MT242353 |

| M. fistulosa(2) | — | IO.14.214 (ARAN-Fungi, S) | ag | MT232352 | KY224088 | MT232495 | MT24237 | — | MT242354 |

| M. juncea s.l. | — | IO.14.177 (S) | ag | MT232353 | MT232306 | MT241267 | — | MT24237 | MT242355 |

| Megacollybia platyphylla | — | TENN 59432 | ag | DQ249275 | AY702016 | AY786053 | DQ447923 | DQ385887 | DQ435786 |

| Mucronella calva(1) | — | JS16142 | cl | — | AY586689 | — | — | — | — |

| M. calva(2) | — | GEL4458 | cl | — | AJ406588 | — | — | — | — |

| M. aff. calva | — | KHL10317 | cl | — | AY586690 | — | — | — | — |

| M. flava | — | IO.16.84 (S) | ag, cl | MT232354 | MT232307 | MT232496 | MT24238 | — | MT242356 |

| M. fusiformis | — | DJM 1309 | ag, cl | — | DQ284905 | — | — | — | — |

| M. pendula | — | PBM 3437 | ag, cl | — | HQ829921 | — | — | — | — |

| Muscinupta laevis | — | V. Haikonen 19745 (H6059292) | hy | MF319066 | MF318921 | MF319004 | — | MF288861 | — |

| Mycetinis alliaceus | — | TENN 55620 | ag | AY854076 | AY635776 | AY787214 | AY860526 | AY786060 | AY883431 |

| Odonticium romellii | — | KHL s. n. (GB) | hy | DQ873639 | DQ873639 | DQ873638 | — | — | — |

| Onnia scaura∗ | — | P53A | hy | genome | Genome | genome | — | genome | — |

| Oxyporus populinus | — | Dai 12793/ DSH 93-188 | hy | KF111019 | KF111021 | AF026616 | — | KT210380 | — |

| Peniophorella praetermissa | — | GEL 2182 (KASSEL) | hy | AY854081 | AY700185 | AY707094 | — | AY787221 | — |

| P. pubera | — | KHL 13154 (GB) | hy | DQ873599 | DQ873599 | DQ873598 | — | — | — |

| Pluteus romellii | — | ECV 3201 (UC) | ag | AY854065 | AY634279 | AY657014 | AY862187 | AY786063 | AY883433 |

| Phaeomarasmius proximans | — | PBM 1951 (WTU) | ag | DQ404381 | AY752970 | AY752970 | — | AY333314 | DQ028592 |

| Phellinidium ferrugineofuscum∗ | — | SpK3Phefer14 | genome | genome | genome | — | genome | — | |

| Phellinus tremulae | — | KCTC 6659/ NJB2011-PT2-F | hy | AY189703 | KU139202 | AY178026 | KU139277 | — | — |

| Phyllotopsis nidulans | — | IO.14.196 (S) | ag, pl | — | MT232308 | MT232497 | MT24239 | MT24238 | MT242357 |

| Phyllotopsis sp. | — | MB 35 (WTU) | ag, pl | DQ404382 | AY684161 | AY707090 | DQ447933 | AY786061 | DQ059047 |

| Porotheleum fimbriatum | — | CBS 788.86 | ag | DQ490626 | DQ457673 | DQ444854 | DQ447907 | DQ472721 | — |

| Pleurocybella porrigens | — | JFA 12544 (WTU)/TUB012154/ UPS F-611822 | ag, pl | MT232355 | MT232309 | GU187660 | DQ067994 | MT24239 | GU187740 |

| Pleurotus eryngii | — | X102 | ag, pl | KX977448 | — | FJ379286 | — | — | — |

| P. ostreatus | — | TENN 53662 | NG_027634 | AY645052 | AY657015 | AY862186 | AY786062 | AY883432 | |

| Plicaturopsis crispa∗ | — | FD-325 SS-3 | ag, pl | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| Podoserpula pusio | — | Hlepp-329 | ag | — | EF535271 | — | — | — | — |

| Porodaedalea pini | — | No-6170-T | hy | JX110037 | JX110081 | — | — | JX109951 | — |

| Pseudoclitocybe cyathiformis | — | JFA 12811 (WTU)/GLM 46020 (GB) | ag | GU187553 | EF551313 | GU187659 | DQ067939 | GU187815 | GU187742 |

| Pterulicium echo(1) | — | DJM 302S58 (MINN) | ag, pl | DQ494693 | AY458123 | DQ092911 | — | GU187805 | GU187743 |

| P. echo(2) | cf. Pterula | ZRL20151311 | pl | LT716065 | KY418881 | KY418947 | KY418979 | KY419026 | KY419076 |

| P. gracile∗(1) | — | CBS 309.79 | ag, pl | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| P. gracile(2) | — | IO.14.142 (S) | pl | MT232356 | MT232310 | MT232498 | — | — | MT242358 |

| Radulomyces confluens∗ | — | OMC1631 | ag, pl | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| R. molaris | — | ARAN-Fungi 2003 | ag, pl | — | MT232311 | MT232499 | MT24230 | MT24230 | MT242359 |

| Ramariopsis biformis | — | JMB10061006 (TENN065660) | cl | — | HQ877712 | — | — | — | — |

| R. crocea | — | JMB10071001 (TENN065661) | cl | — | HQ877715 | — | — | — | — |

| R. aff. kunzei | — | Marr5064 (WTU) | cl | — | HQ877719 | — | — | — | — |

| R. pseudosubtilis | — | RHP27722 (TENN027722) | cl | — | HQ877723 | — | — | — | — |

| R. tenuiramosa | — | GG_061104 | cl | — | EF535269 | — | — | — | — |

| Repetobasidium conicum | — | KHL 12338 (GB) | hy | DQ873647 | DQ873647 | DQ873646 | — | — | — |

| R. mirificum | — | FP-133558-sp | hy | — | AY293208 | AY293155 | — | — | — |

| Resinicium bicolor | — | GEL 2071 (KASSEL) | hy | DQ218310 | AY700183 | — | — | DQ457635 | — |

| Rickenella fibula | — | PBM 2503 (WTU) | hy | DQ241782 | AY700195 | AY771599 | — | DQ408115 | — |

| Rhodocollybia maculate | — | WTU | ag | DQ404383 | AY639880 | AY752966 | DQ447936 | AY787220 | DQ061279 |

| Sarcomyxa serotina | — | WTU/ DSH 93-218 | ag, pl | DQ494695 | AY691887 | AF026590 | DQ447938 | DQ859892 | GU187754 |

| Schizophyllum radiatum | — | FH | ag | AY571060 | AY571023 | AY705952 | DQ447939 | DQ484052 | — |

| Schizopora radula | — | Dai 12631 | hy | KT203307 | KT203328 | — | — | KT210382 | — |

| Sclerotium complanatum | Macrotyphula phacorrhiza | Microf. Exs. No. 49 (UPS) | pl | — | MT234400 | — | — | — | — |

| Sistotrema confluens | — | FCUG 298 | hy | DQ267125 | AY647214 | AY757260 | — | DQ381837 | — |

| Stephanospora caroticolor | — | TUB019072/ IOC 137-97/ R44008 | ag, pl | KM086827 | AF518652 | AF518591 | KF211335 | — | GU187747 |

| Trichaptum abietinum∗ | — | R44008 | hy | genome | genome | genome | — | genome | — |

| Tubulicrinis globisporus | — | KHL 12133 (GB) | hy | DQ873655 | DQ873655 | DQ873654 | — | — | — |

| T. inornatus | — | KHL 11763 (GB) | hy | DQ873659 | DQ873659 | DQ873658 | — | — | — |

| Tygervalleyomyces podocarpi | Typhula podocarpi | CPC 29979 | NR_156661 | NG_059851 | — | — | — | — | |

| Typhula capitata | — | IO.15.122 (S, UPS)/ CBS 143727 | ag, pl | MT232357 | MT232312 | MT232500 | MT24231 | MT24231 | MT242360 |

| T. crassipes | — | IO.14.83 (S, UPS) | ag, pl | MT232358 | KY224094 | — | — | MT24232 | MT242361 |

| T. erythropus | — | IO.14.123 (S, UPS)/ CBS 143797 | ag, pl | MT232359 | KY224096 | MT232501 | MT24232 | MT24233 | MT242362 |

| T. gyrans | — | IO.14.103 (S)/ CBS 143796 | ag, pl | MT232360 | KY224097 | MT232502 | MT24233 | MT24234 | MT242363 |

| T. micans | — | IO.14.165 (S) | ag, pl | MT232361 | KY224102 | MT232503 | MT24234 | MT24235 | MT242364 |

| T. incarnata | — | IO. 14. 92 (S)/ CBS 143742/ CBS 350.79 | ag, pl | MT232362 | MT232313 | MT232504 | MT24235 | MT24236 | MT242365 |

| T. phacorrhiza(1) | Macrotyphula phacorrhiza | IO.14.200 (S) | ag, pl | MT232363 | MT232314 | MT232505 | — | MT24237 | MT242366 |

| T. phacorrhiza(2) | M. phacorrhiza | IO.14.167 (S) | ag, pl | MT232364 | MT232315 | MT232506 | MT24236 | MT24238 | MT242367 |

| T. phacorrhiza(3) | M. juncea s.l. | DSH 96-059 | pl | — | AF393079 | AF026630 | — | AY218525 | — |

| T. phacorrhiza(4) | M. phacorrhiza | ARAN-Fungi 7446 | pl | — | MT232316 | — | — | — | MT242368 |

| T. sclerotioides | — | IO.14.22 (S) | ag, pl | MT232365 | MT232317 | MT232507 | MT24237 | MT24239 | MT242369 |

| T. subhyalina | — | IO.15.06 (S)/ CBS 143735 | ag, pl | MT232366 | MT232318 | MT232508 | — | MT24230 | MT242370 |

| T. uncialis | — | IO.14.74 (S) | ag, pl | MT232367 | MT232319 | MT232509 | MT24238 | MT24231 | MT242371 |

| Uncultured Basidiomycota(5) | Ceratellopsis sp. | Soil sample | cl | DQ341741 | DQ341741 | — | — | — | — |

| Uncultured Basidiomycota(1) | Ceratellopsis sp. | Soil sample | cl | HQ433218 | HQ433218 | — | — | — | — |

| Uncultured Basidiomycota(2) | Ceratellopsis sp. | Soil sample | cl | GQ159941 | GQ159941 | — | — | — | — |

| Uncultured Basidiomycota(3) | Ceratellopsis sp. | Soil sample | cl | EU691875 | EU691875 | — | — | — | — |

| Uncultured Basidiomycota(4) | Ceratellopsis sp. | Soil sample | cl | EU861817 | EU861817 | — | — | — | — |

| Uncultured Basidiomycota(5) | Ceratellopsis sp. | Soil sample | cl | DQ341741 | DQ341741 | — | — | — | — |

| Uncultured Basidiomycota(6) | Ceratellopsis sp. | Soil sample | cl | EF434117 | EF434117 | — | — | — | — |

| Uncultured Basidiomycota(7) | Ceratellopsis sp. | Soil sample | cl | GQ159939 | GQ159939 | — | — | — | — |

| Xerula radicata | — | TENN 59235 | ag | DQ241780 | AY645051 | AY654884 | DQ447946 | AY786067 | DQ029194 |

| Xylodon rimosissimus | — | CBS 105.045/ Ryberg 021031 (GB) | hy | DQ873627 | DQ873628 | DQ873626 | — | LN714662 | — |

Results

Origins of typhuloid fungi within Agaricales and Pleurotineae

A total of 118 (21 5.8S, 23 28S, 18 18S, 13 RPB1, 23 RPB2, 20 EF-1α) sequences were generated for this study (Table 2). The Agaricales matrix comprised 81 taxa and contained 6 292 unambiguously aligned nucleotide positions (161 nu5.8S, 1 480 nu28S, 1 745 nu18S, 861 RPB1, 1 056 RPB2 and 989 EF-1α), with all genes available for 86.4 % of taxa. The Pleurotineae matrix had 39 taxa and contained 6 215 unambiguously aligned nucleotide positions (159 nu5.8S, 1 418 nu28S, 1 732 nu18S, 863 RPB1, 1 056 RPB2 and 987 EF-1α), with all genes available for 72.2 % of taxa. The Bayesian analysis of the Agaricales and Pleurotineae datasets reached average standard deviations of split frequencies > 0.01 after 12 195 000 and 425 000 generations, respectively. The Bayesian majority rule consensus tree of the Agaricales was fully resolved and many deeper branches received high support by Bayesian PP (Fig. 2). The majority of these branches were, however, not supported by ML-BP (< 70 %). Typhuloid fungi do not form a monophyletic group. Specimens with skeletal hyphae nest in Pleurotineae (Pterulicium gracile) and in Clavariineae (C. acuminata). Sequences of the specimen of P. gracile collected by us (IO.14.142) were identical to those obtained from the available genome of P. gracile (CBS 309.79) (Fig. 3), employed also by Leal-Dutra et al. (2020). Clavariineae forms a strongly supported clade (PP 1, ML-BP 86) that is resolved as an early diverging lineage within Agaricales (PP 1). Ceratellopsis acuminata forms a highly supported clade with Ramariopsis kunzei (PP 1, ML-BP 100). The remaining Agaricales form a strongly supported monophyletic group (PP 1), within which Ampulloclitocybe clavipes, Cantharocybe gruberi, Hygrocybe coccinea, Hygrophorus pudorinus and Pseudoarmillariella ectypoides, corresponding to the Hygrophoraceae, constitute a strongly supported lineage in the Bayesian analysis (PP 0.98), as a sister group to the rest of the Agaricales (PP 1). The suborders Agaricineae (PP 0.96), the Tricholomatineae (PP 1), the Marasmiineae (PP 0.99) and the Pluteineae (PP 0.95) also received high support in the Bayesian analysis. Xeromphalina campanella, previously assigned to the hygrophoroid clade, is supported as an early diverging sister lineage to the Marasmiineae (PP 0.99). Species of Typhula and Macrotyphula form a well-supported clade together with other pleurotoid, clavarioid, corticioid and gasteroid species (PP 0.95) that is referred to the Pleurotineae. The Agaricales (ag) and Pleurotineae (pl) phylogenies (Fig. 2, Fig. 3) show similar supported nodes in the Pleurotineae, except that the Pleurotaceae formed a sister group to the rest of the Pleurotineae in both Bayesian and ML analyses of the Pleurotineae matrix (PP 1, ML-BP 99). In all analyses T. phacorrhiza is nested within a monophyletic Macrotyphula (ag PP 1, ML-BP 100; pl PP 1, ML-BP 100). A specimen identified as Sclerotium complanatum is nested within a clade of three T. phacorrhiza collections in the analyses of the Pleurotineae matrix. The Macrotyphula clade is encompassed in a larger supported clade together with Phyllotopsis and Pleurocybella porrigens (pl PP 1). Stephanospora caroticolor, Cristinia rhenana, Pterulaceae and Radulomycetaceae (Aphanobasidium, Radulomyces) form a strongly supported clade (pl PP 1, ML-BP 73) sister to the Macrotyphula clade, Phyllotopsis and Pleurocybella porrigens. All Typhula species but its type T. phacorrhiza, form a distinct separate lineage (pl PP 1, ML-BP 100). It includes the types of Cnazonaria, Dacryopsella, Gliocoryne, Phacorhiza, Pistillaria, Pistillina, Scleromitra, Sphaerula and Tygervalleyomyces. Typhula is a sistergroup to the clade formed by Macrotyphula, Phyllotopsis, Pleurocybella porrigens, Pterulaceae and Stephanosporaceae in the Pleurotineae phylogeny (Fig. 3), albeit without support (pl PP 0.94). Pleurotus and Hohenbuehelia tremula are supported as a sistergroup to the rest of the Pleurotineae in the Pleurotineae phylogeny (Fig. 3, PP 1, ML-BP 99).

Fig. 2.

Bayesian inference 50 % majority rule consensus phylogram of the Agaricales from 5.8S-18S-28S-RPB1-RPB2-EF-1α sequence data, with the placement of typhuloid fungi (in blue font). Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) and Maximum Likelihood bootstrap values (ML-BP) are shown on branches, ordered as PP/ML-BP. Thickened branches received support at least in one analysis (ML-BP ≥ 70 % and/or PP ≥ 95 %). Suborder names recognised within the Agaricomycetes are indicated on the right side.

Fig. 3.

Bayesian inference 50 % majority rule consensus phylogram of the Pleurotineae from 5.8S-18S-28S-RPB1-RPB2-EF-1α sequence data. Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) and Maximum Likelihood bootstrap values (ML-BP) are shown on branches, ordered as PP/ML-BP. Thickened branches received support at least in one of the analyses (ML-BP ≥ 70 % and/or PP ≥ 95 %). Family names recognised within the Pleurotineae are marked with colour boxes. Basidioma types are indicated with different colours for ingroup taxa.

The Clavariaceae phylogeny

The Clavariaceae matrix comprised 53 taxa and contained 1 505 unambiguously aligned nucleotide positions (28S rDNA). Bayesian and ML analyses produced very similar topologies (Fig. 4). Species of Mucronella form a highly supported sister group to the rest of the Clavariaceae (PP 1, ML-BP 100). Clavaria, Camarophyllopsis, Hodophilus and Hirticlavula elegans form a highly supported monophyletic group (PP 1, ML-BP 84), characterised by lacking clamp connections on context hyphae in all species but Clavicorona taxophila. Three species of Ceratellopsis form a distinct clade with several environmental sequences (uncultured Basidiomycota in GenBank). The relationships of the Ceratellopsis clade to the other genera with clamp connections, Ramariopsis and Clavulinopsis, are not resolved with support.

Fig. 4.

Bayesian inference 50 % majority rule consensus phylogram of the Clavariineae from 28S sequence data. Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) and Maximum Likelihood bootstrap values (ML-BP) are shown on branches, ordered as PP/ML-BP. Thickened branches received support at least in one analysis (ML-BP ≥ 70 % and/or PP ≥ 95 %). Basidioma types are indicated with different colours for ingroup taxa.

The Hymenochaetales phylogeny

The Hymenochaetales matrix contained 37 taxa and 4 239 unambiguously aligned characters. The majority rule consensus tree of the Bayesian analysis is provided in Fig. 5. The Hymenochaetales is recovered as monophyletic with high support in the Bayesian analysis (PP 1, ML-BP 62). It comprises two larger clades: a) a clade containing Coltricia, Kneiffiella, Xylodon and Hymenochaetaceae, corresponding to clades C–F in Larsson et al. (2006), along with two species of Repetobasidium (PP 0.91, ML-BP 26); and b) a clade corresponding to the Rickenella clade (clade B in Larsson et al. 2006) (PP 1, ML-BP 57). Within the Rickenella clade, the three Ceratellopsis sagittiformis specimens are encompassed in a well-supported clade (PP 1, ML-BP 65) with species of agaricoid (Blasiphalia, Cantharellopsis, Gyroflexus, Rickenella), clavarioid (Alloclavaria), corticioid (Globulicium, Hyphodontia, Peniophorella, Resinicium), cyphelloid (Muscinupta) and thelephoroid (Cotylidia) basidiomata. The position of Hyphodontia alutaria and Resinicium bicolor is in conflict; both species form a supported monophyletic group with Rickenella fibula and C. sagittiformis in the Bayesian analysis (PP 99), as opposed to a monophyletic group with Cotylidia spp. in the ML analysis (ML-BP 75).

Fig. 5.

Bayesian inference 50 % majority rule consensus phylogram of the hymenochaetoid clade from 5.8S-18S-28S-RPB2 sequence data. Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) and Maximum Likelihood bootstrap values (ML-BP) are shown on branches, ordered as PP/ML-BP. Thickened branches received support at least in one analysis (ML-BP ≥ 70 % and/or PP ≥ 95 %). Basidioma types are indicated with different colours for ingroup taxa.

Taxonomy

Clavariineae Olariaga, Huhtinen, Læssøe, J.H. Petersen & K. Hansen, subord. nov. MycoBank MB831365.

Basidiomata clavarioid, more rarely agaricoid with waxy decurrent gills, or corticioid. Hyphal system monomitic, or more rarely dimitic. Basidiospores hyaline, usually thin-walled, smooth or ornamented, usually with multiguttulate contents, sometimes with amyloid or dextrinoid reactions, usually with a cubic apiculus. Basidia claviform, with up to 4 sterigmata, chiastic, sometimes characteristically long (< 50 μm) or short (> 20 μm), occasionally sometimes with a loop-like basal clamp (Clavaria subgen. Holocoryne). Cystidia usually absent. Pileipellis either a hymeniderm or a trichoderm with rounded terminal elements in genera with agaricoid basidiomata. Basal tomentum composed of narrow, usually < 2 μm broad thick-walled hyphae in clavarioid genera (Ceratellopsis, Clavaria, Clavulinopsis, Ramariopsis), possibly also in other stipitate genera. Clamp connections present or absent, sometimes restricted to basidia. Saprotrophic on dead wood, herbaceous plants or leaves, or biotrophic with grasses and bryophytes. Presence of EF-1α intron 21 (numbering according to Matheny et al. 2007) in some genera (absent in Ceratellopsis).

Type family: Clavariaceae Chevall.

Notes: This suborder contains a single family. Similar isotopic ratios to those found in the Hygrophoraceae suggest that at least non-lignicolous members of Clavariaceae have some kind of biotrophic association with plants (Birkebak et al. 2013), whereas genera occurring on dead plant remnants are probably saprotrophic (Ceratellopsis, Mucronella, Hirticlavula). Very narrow and slightly thick-walled hyphae in the basal tomentum and mycelium are characteristic for many species of Clavariaceae, including species in Clavaria, Clavulinopsis, Ramariopsis (Olariaga 2009) and Ceratellopsis (Fig. 6) and it might be a synapomorphic character of the Clavariineae. The presence of EF-1α intron 21, absent in the rest of the Agaricales (Matheny et al. 2007) seems so far unique to some Clavariaceae (Clavaria, Clavulinopsis, Camarophyllopsis).

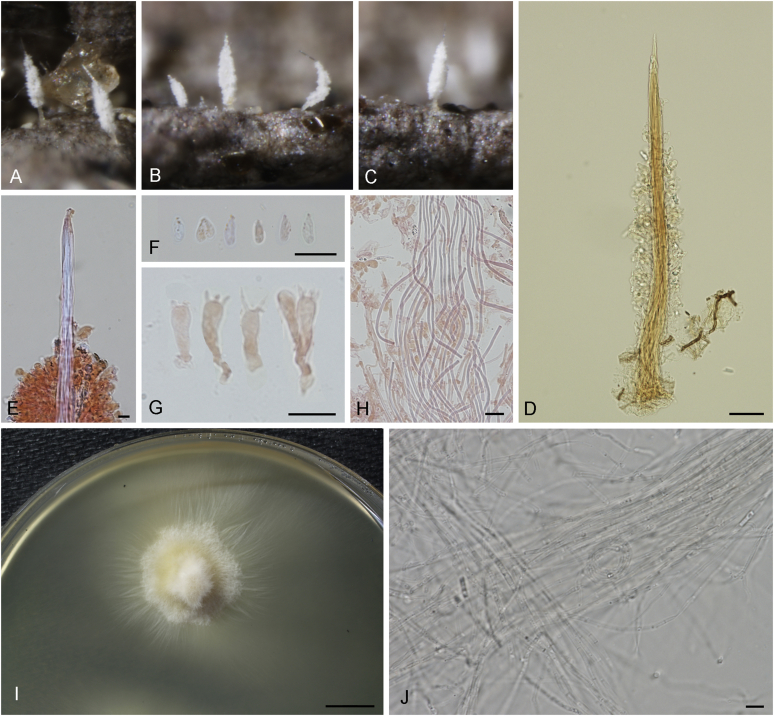

Fig. 6.

Ceratellopsis acuminata (epitype, Huhtinen 15/07, S). A–C. Dried basidiomata. D. Basidioma observed using a light microscope. E. Close-up of basidioma apex. F. Basidiospores. G. Basidia. H. Medullar hyphae resembling skeletal hyphae. I. One-year-old culture in MEA, kept at 5 °C (culture ex-epitype, CBS 146691). J. Hyphae from cultured mycelium (culture ex-epitype, CBS 146691). Mounting media were Melzer's reagent (D), Congo Red in ammonia (E–H) and water (I). Scale bars: D = 100 μm, E–H = 10 μm; I = 10mm. Photographs I. Olariaga.

Clavariaceae Chevall., Fl. Gen. Env. Paris 1: 102. 1826. [“Clavariae”; “ordre”; considered family according to Art. 18.2].

Type genus: Clavaria Vaill. ex L. : Fr.

Genera: Camarophyllopsis, Ceratellopsis, Clavaria, Clavulinopsis, Hirticlavula, Hodophilus, Hyphodontiella, Mucronella, Ramariopsis.

Ceratellopsis Konrad & Maubl., Icon. Select. Fung. 6: 502. 1937.

Basionym: Ceratella Pat., Hymenomyc. Eur.: 137. 1887. [nom. illeg. Art. 53.1, later homonym of Ceratella Hook f. 1844].

Presumed saprobic on bark, dead wood or culms. Basidiomata gregarious, clavarioid, 0.2–1(–2) mm high, lanceolate with a sterile pointed apex, white. Stipe usually present, short, glabrous or pubescent. Hyphal system monomitic or dimitic. Basidiospores without iodine reactions. Basidia claviform, short, 10–16 μm long. Generative hyphae present in the medulla, unidirectional, cylindrical, septate, thick-walled, 1–2.5 μm broad, sometimes dextrinoid. Skeletal hyphae present in the medulla of C. acuminata and further undescribed species known by us. Clamp connections scattered.

Type: Ceratellopsis acuminata (Fuckel) Corner, typ. cons. prop.

Notes: The background of the name Ceratellopsis requires, however, further clarification as its type has been a matter of controversy. According to our nomenclatural study, Ceratellopsis is a validly published replacement name based on Ceratella Pat. and typified by Pistillaria queletii. The final epithet Ceratella was first employed by Quélet (1886) for an unranked infrageneric name. Later, although Patouillard (1887) referred to Ceratella as “CERATELLA (Quél.)” he did not have in mind Clavaria [unranked] Ceratella as the basionym of a new combination. As explained in the introduction of the Hyménomycètes (Patouillard 1887: VII), authors of generic names were cited between round brackets only when Patouillard's circumscriptions were absolutely different from the original ones. Therefore, we consider Ceratella as the name of a new taxon to be cited as “Ceratella Pat.” (J. McNeill, pers. comm.) in agreement with Donk (1954) and the ING (Farr & Zijlstra 2020). Nevertheless, Ceratella Pat. (1887) is illegitimate as a later homonym of Ceratella Hook f. (1846). When Ceratellopsis was introduced, Konrad & Maublanc (1937) referred to it as a new name for “Ceratella (Quélet p.p.), Patouillard (1887)” and proposed Ceratellopsis queletii as the type, without providing a Latin description. Since Ceratellopsis was a replacement name for Ceratella Pat., and not a new taxon, Ceratellopsis is a validly published generic name even though it lacked a Latin description and was published later than 1935 (Art. 39.1), because such is not required for a replacement name. The type proposed for Ceratellopsis by Konrad & Maublanc is also in order, since Ceratella queletii was one of the three species listed under Ceratella Pat. (1887). A relevant fact that might have affected the typification of Ceratellopsis is whether the combination Ceratella queletii was validly published when Patouillard erected Ceratella Pat. Patouillard (1887) listed C. queletii as “C. Queletii” without explicitly citing its basionym Pistillaria queletii. However, we interpret that Patouillard (1887: VI) gave an indirect reference to the basionym that fulfils conditions for valid publication of C. queletii (Art. 41.3 and 38.14) by explicitly stating that Tabulae Analyticae Fungorum, the place of publication of Pistillaria queletii, basionym C. queletii, was one of the main works on which he based his Hyménomycètes (Art. 41.4, Ex. 9), and because Patouillard himself was author of the basionym.

For details on our choice to suggest C. acuminata as the conserved type for Ceratellopsis see notes under Pterulicium and the Discussion.

Ceratellopsis acuminata (Fuckel) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 202. 1950. Fig. 6.

Basionym: Pistillaria acuminata Fuckel, Fungi Rhen. Exs. (suppl.) 4: no 1888. 1867.

Synonym: Ceratella acuminata (Fuckel) Pat., Essai Tax. Hyménomyc.: 49. 1900.

Basidiomata gregarious, 0.2–0.4 mm high, simple, with a short stipe and a sterile apex. Fertile part cylindrical to oblong, sharply delimited from the stipe and the apex, white, 0.1–0.3 × 0.02–0.04 mm. Stipe short, cylindrical, glabrous, hyaline white, 0.04–0.12 × 0.01–0.02 mm. Apex pointed, acute, hyaline white, 0.04–0.1 mm long. Basidiospores ellipsoid to pip-shaped, sometimes in tetrads, hyaline, without iodine reactions, (3–)4–6 × (1.5–)2–3 μm. Basidia claviform, 2–4-spored, 10–16 × 3.5–4.5 μm, clamped. Generative hyphae cylindrical, hyaline, thin-walled, clampless, sometimes with scarce septa at the stipe base, 1–2.2 μm broad. Skeletal hyphae present in the medulla, cylindrical, refractive, slightly dextrinoid, 1.2–2.8 μm broad. Colonies on MEA 30–40 mm diam after 1 yr at 5 °C, superficial, effuse, convex, tomentose, hard-textured, with erect white tufts and strong smell reminiscent of Scleroderma. Reverse white. Margin regular and distinct. Vegetative hyphae cylindrical, closely septate, very slightly thick-walled, hyaline, 2.5−4 μm broad, with scattered clamp connections. Asexual morph not observed in culture.

Typus: Germany, Nassau, Johannisberger Schlosswald, ad pini sylv. folia putrida falae humus, Fuckel, Fungi Rhen. Exs. no 1888 (S-F128455 !, lectotype of Pistillaria acuminata designated here, MycoBank MBT387677). Isolectotypes: S-F128454 (!), S-F267533 (!), FH00608504 (!), K(M) 159801, M. Sweden, Härjedalen, Tänndalen, Hamrafjället Nature Protection Area, on dead leaves of Dryas octopetala, 4 Aug. 2015, S. Huhtinen 15/07 (S, epitype of Pistillaria acuminata designated here, MycoBank MBT389356). Culture ex-epitype: CBS 146691.

Known distribution: Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Norway, Spain and Sweden.

Additional materials examined: Denmark, Sjælland, Bognæs skov, on leaves of Leymus on exposed beach, 26 Oct. 2019, T. Læssøe, DMS-10058526 (C). Finland, Perä-Pohjanmaa, Rovaniemi, Lovevaara Nature Protection area, brookside herb-rich forest, on leaf litter under alders, 7 Sep. 2012, S. Huhtinen 12/15 (TUR 197690). France, Val-d'Oise, Montmorency, ad cortices, 1889, Boudier herbarium (PC). Norway, Finnmark, Nord Varanger, Varanger Peninsula, Fosefjellet (ca. 3 km NW of Vadsö), on hare dung (Lepus tumidus) in moist chamber, 27 Jul. 1966, N. Lundqvist 4965g (UPS F-152857). Sweden, Gästrikland, Gävle, Lövudden, Salix viminali, folia dejecta, 25 Jun. 1953, J.A. Nannfeldt 12806 (UPS F-152650, as Ceratellopsis sp.); Lycksele Lappmark, Saxnäs, Satsfjället, on dead fern stems, 28 Jul. 2010, K. Hansen, K. Gillen & I. Olariaga, IO.10.01 (S); Västergötland, Håkantorp, Äspås hållplats, on Quercus robur leaves, 2 Oct. 1955, S. Kilander (UPS F-152830).

Notes: Ceratellopsis acuminata differs from C. aculeata in having skeletal hyphae in the basidioma core. Another collection identified as C. aff. acuminata by us (ARAN-Fungi 11746) possessed also skeletal hyphae, but had longer and shorter basidiomata and nested in a different clade than the epitype of C. acuminata (Fig. 4). This substantiates the idea that an additional species of Ceratellopsis exists and when more specimens become available the species limits should be studied further.

Corner (1950: 203) mentioned a type collection of Pistillaria acuminata (that Donk had examined in ms) without providing a collection number or a herbarium. Since we believe that Corner's type indication did not fulfil requirements for achieving a valid typification (Art. 7.11), we propose here a lectotypification of C. acuminata. The four syntypes examined are very meagre. Therefore, we select as epitype a recent collection from which a living culture and several gene regions have been obtained. We found C. acuminata to have a very broad host range and distribution, and feel justified in selecting Swedish material collected on Dryas leaves as epitype.

Ceratellopsis aculeata (Pat.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 200. 1950.

Basionym: Pistillaria aculeata Pat., Tab. anal. Fung. 1: 26. 1883.

Synonyms: Ceratella aculeata Pat., Essai Tax. Hyménomyc.: 49. 1900.

(?) Pistillaria mucedinea Boud., Bull. Soc. bot. Fr. 24: 308. 1878. [1877].

(?) Ceratellopsis mucedinea (Boud.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 204. 1950.

Typus: No type specimen in the Patouillard herbarium (FH, PC). Lectotype of Pistillaria aculeata designated here: Patouillard, Tab. Anal. Fung. 1: fig. 58. 1883. MycoBank MBT387467.

Specimens examined: Denmark, Lolland, Maribo Søndersø, on stems of Cladium mariscus, 9 Oct. 2000, T. Læssøe, DMS-376001 (C). Spain, Aragón, Huesca, on Pinus bark, 26 Feb. 2017, R. Blasco, ARAN-Fungi 13729; Basque Country, Gipuzkoa, Larraul, Usarrobi erreka, 9 Jun. 2012, I. Olariaga, ARAN-Fungi A3064020. Sweden, Öland, Norra Mosse, on damp, dead parts of Cladium, 2 Jul. 1988, S. Elborne, C-F-94548. UK, England, Wicken fen, on Cladium mariscus, 12 Aug. 1926, E.J.H. Corner (PC).

Notes: Medulla hyphae in Ceratellopsis aculeata are thick-walled and have scarce septa, as noted by Corner (1950). Originally described as occurring on fallen leaves, C. aculeata has been considered to typically occur on dead leaves of Cladium mariscus (Corner, 1950, Hansen and Knudsen, 1997). Specimens collected on bark or dead wood share a similar basidioma configuration, hyphae and spores.

As Corner (1950) suggested Pistillaria mucedinea is very close to C. aculeata. The small size of basidiomata (0.5–0.75 mm) and the 4-spored basidia described in the protologue support this view. Furthermore, our study of an authentic specimen kept at PC, collected on bark as described in the protologue, has scarcely septate thick-walled hyphae as observed in the material on Cladium mariscus. We agree with Corner (1950) and even suggest P. mucedinea might be conspecific with C. aculeata and list it as a possible earlier synonym. However, a better insight on species limits in Ceratellopsis needs to be acquired to further test this.

Names formerly placed in Ceratellopsis and imperfectly known, excluded here or illegitimate

Ceratellopsis aciculata (Durieu & Lév. ex Sacc.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 200. 1950.

Basionym: Pistillaria aciculata Durieu & Lév. ex Sacc., Syll. Fung. 6: 759. 1887.

Typus: Lectotype designated here: Bory de Saint-Vincent & Durieu de Maisonneuve, Expl. Sci. Algérie 1(5): tab. 32, fig. 4. 1846. MycoBank MBT387461.

Notes: Pistillaria aciculata, published as a nomen nudum (Bory de Saint-Vincent & Durieu de Maisonneuve 1846), was invalid until Saccardo provided a description. The illustration provided by Bory de Saint-Vincent & Durieu de Maisonneuve (1846) shows brown, pointed acute structures that do not look like a fertile fungus but rather incipient basidiomata of a marasmioid fungus. This figure is, to our knowledge, the only original element and it is accordingly proposed as lectotype.

Ceratellopsis asphodeli (Pat.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 203. 1950.

Basionym: Ceratella microscopica var. asphodeli Pat., Cat. Pl. Cell. Tunisie: 66. 1897.

Typus: No type specimen in the Patouillard herbarium (FH, PC). No original illustration.

Notes: The 2-spored basidia and the presence of cystidia described in Patouillard (1897) suggest that C. asphodeli is a synonym of Pterulicium gracile. The pink tones can be present in P. gracile (Olariaga 2009).

Ceratellopsis biformis Khurana in Berthier, Bull. Soc. Linn. Lyon. 45: 190. 1976 [nom. illeg., Art. 39, 40].

Notes: The description provided by Berthier (1976) based on Corner's notes of a fungus on Quercus leaves from India suggests that C. biformis may belong to Ceratellopsis as conceived here due to its narrow, 1.5–2 μm broad, medulla hyphae. Nevertheless, C. biformis was never validly published since neither a Latin diagnosis nor a type specimen were provided for it.

Ceratellopsis brondaei (Quél.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 203. 1950.

Basionym: Clavaria brondaei Quél., Revue mycol. (Toulouse) 14(54): 65. 1892.

Typus: No type specimen in PC and TL.

Notes: Quélet (1892) described C. brondaei apparently based only on the Brondeau plate no. 165 (“Alb. 165”). The illustration provided in the protologue (plate 126, fig. 3), probably a reproduction of plate no. 165, shows a small white clavarioid fungus, said to grow in forest on soil among tiny mosses. The description, except the ecology, tallies with a species of Ceratellopsis as treated here, but in the absence of microscopic information and a type specimen, a reliable interpretation cannot be provided, as Corner (1950) stated.

Ceratellopsis caespitulosa (Sacc.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 203. 1950.

Basionym: Pistillaria caespitulosa Sacc., Atti del Congr. bot. di Palermo. 1902.

Typus: [from Saccardo, Syll. Fung. 17: 202. 1905]: France, Côte d’Or, in cortice emortuo Loniceræ periclymeni [Lonicera periclymenum], PAD.

Notes: The denticulate “basidia” and the 1-septate biguttulate spores suggest that C. caespitulosa is an asexual morph fungus, probably conspecific with Isaria friesii (Leotiomycetes, Ascomycota).

Ceratellopsis carestiae (Ces.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 203. 1950.

Basionym: Pistillaria carestiae Ces. in Bres. & Sacc., Malpighia 11: 255. 1897.

Typus: Italy, Piemonte, Alagna Valsesia, sur ramis secchiSyringa vulgaris, 13 Oct. 1857, Ab. Carestia no 27 (S-F15983 !, ex Bresadola herbarium; lectotype designated here, MycoBank MBT387464).

Notes: The material constitutes an asexual fungal state growing on bark, very probably conspecific with Isaria friesii. The spore content, described as divided in two (“plasma bipartito”) is due, in fact, to the 1-septate spores, as in C. caespitulosa (see above).

Ceratellopsis corneri Berthier, Bull. mens. Soc. linn. Lyon 43: 188. 1974.

Typus: France, Lyon, Soucieu-en-Jarrest, sur l´ecorce pourrissante d'un arbre abattu (Gymnosperme?), Bussy, 11 Apr. 1970 (holotype G).

Notes: Due to the 4–6 μm broad medulla hyphae and the amyloid spores, C. corneri does not conform to Ceratellopsis. We consider it that C. corneri should be examined and compared to Mucronella instead.

Ceratellopsis dryopteridis (S. Imai) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 203. 1950.

Basionym: Pistillaria dryopteridis S. Imai, Sapporo Trans. Sapporo nat. Hist. Soc. 13(4): 386. 1934.

Typus: Japan, Ishikari province, Nov. probably at SAPA.

Notes: The filiform 1–5 mm long basidiomata and 9–12.5 μm long spores suggest that C. dryopteridis should not be excluded from Ceratellopsis. The spores of C. dryopteridis are asperulate and therefore a relationship with Pterula is suggested here, but the type specimen, if it exists, should be examined to confirm this.

Ceratellopsis equiseticola (Boud.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 204. 1950.

Basionym: Pistillaria equiseticola Boud., Bull. Trimestr. Soc. Mycol. France 33(1): 13. 1917.

Typus: France, Saône-et-Loire, Clovey (?), ad caules Equiseti limosi [Equisetum fluviatile], May 1915, Boudier herbarium (PC !, as P. equisetina; lectotype designated here, MycoBank MBT387465).

Notes: As earlier suggested by Berthier (1976), we conclude that C. equiseticola is a synonym of P. gracile after examining type material.

Ceratellopsis graminicola (Bourdot & Galzin) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 204. 1950.

Basionym: Pistillaria graminicola Bourdot & Galzin, Hymenomyc. France: 139. 1928.

Typus: No type specimen in the Bourdot & Galzin herbarium (PC). No original illustration.

Notes: The 12–18 μm long, 2–4-spored basidia, small spores (6–7 × 4 μm) and narrow, 1.5–2.5 μm broad hyphae given in the original description would indicate that C. graminicola should be retained in Ceratellopsis, rather than being conspecific with P. gracile. It might be conspecific with C. aculeata or C. acuminata, but details on its hyphal structure are necessary to provide a solid interpretation.

Ceratellopsis helenae (Pat.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 204. 1950.

Basionym: Pistillaria helenae Pat., Tab. Anal. Fung. 1: 26. 1883.

Typus: No type specimen in the Patouillard herbarium (FH, PC). Lectotype designated here: Patouillard, Tab. Anal. Fung. 1: fig. no. 57. 1883. MycoBank MBT387466.

Notes: The forked or sparsely branched basidiomata, with a tendency to be caespitose, and the presence of a distinct stipe, suggest that C. helenae is a synonym of Typhula crassipes. Although basidiomata of T. crassipes are usually simple, we have observed branched basidiomata as those depicted in the lectotype figure. Also, 2-spored basidia and incarnate tones are sometimes present in T. crassipes (Olariaga 2009). Corner (1950) compared C. helenae to P. gracile, but the latter lacks a stipe.

Ceratellopsis kubickae Pilát, Česká Mykol. 12(4): 217. 1958.

Typus: Czech Republic, prope Třeboň, ad folium putridum Salicis auritae [Salix aurita], 15 May 1958, Kubíčka (PRM 655767).

Notes: Pilát (1958) described C. kubickae as monomitic and compared it with P. gracile. Berthier (1976) investigated the type material and proposed that C. kubickae is a synonym of P. gracile, and that Pilát (1958) overlooked skeletal hyphae. In our opinion, the 2-spored basidia and the absence of a stipe in C. kubickae support it is a synonym of P. gracile.

Ceratellopsis mucosa (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 205. 1950.

Basionym: Typhula mucosa Berk. & M.A. Curtis, Grevillea 2(14): 18. 1873.

Typus: USA, South Carolina, Society Hill, in herb. mort., 1852, Carolina inf. No. 3832 (syntypes FH 596847, K).

Notes: The original description is very meagre, and we are unable to propose a reliable interpretation without checking type material. Corner (1950) failed also to provide a specific interpretation and stated that C. mucosa “may be Ceratellopsis, Pterula, or a rudimentary Pistillaria”.

Ceratellopsis rickii (Oudem.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 205. 1950.

Basionym: Mucronella rickii Oudem., Ned. kruidk. Archf., 3 sér. 2(3): 667. 1902.

Synonym: Cnazonaria rickii (Oudem.) Donk, Meded. Bot. Mus. Herb. Rijks Univ. Utrecht 9: 99. 1933.

Typus: The Netherlands, Limburg, Valkenburg, in caulibus herbarum praesertim Asparagi off. [Asparagus officinalis], May 1901, J. Rick, herb. Oudemans (holotype L). Isotype: Bourdot & Galzin herbarium (PC !).

Notes: Jülich (1980) reduced C. rickii to a synonym of P. gracile after examining type material. We confirm this synonymy based on characters seen on the cited isotype.

Ceratellopsis rosella (Fr.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 206. 1950.

Basionym: Pistillaria rosella Fr., Epicr. syst. mycol.: 587. 1838. [1836–1838].

Typus: No type specimen in the Fries herbarium (UPS). No original illustration.

Notes: The pink colour described in the protologue is almost unique to T. micans among typhuloid fungi and we thus agree with Berthier (1976) in considering C. rosella a synonym of T. micans.

Ceratellopsis sydowii (Bres.) Corner, Ann. Bot. Mem. 1: 206. 1950.

Basionym: Clavaria sydowii Bres. in Sydow, Hedwigia 35: (61). 1896.

Typus: Germany, Saxony, Muskau, O.L. Bergpark, ad ramulos Robiniae pseudoacaciae, Jul. 1895, P. Sydow, Mycoth. March. 4405 (syntypes CHRB, MIN, NCU).