Abstract

Polymyxin B has been considered to be the last line of defense for life-threatening infections caused by multiple drug resistant gram-negative pathogens, including carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA). The present study analyzed CRPA resistance to polymyxin B in the Suzhou district of China. Additionally, polymyxin B resistance rates were compared in different parts of the world to determine global trends. The present study also assessed the reliability and effectiveness of the Etest® in a clinical setting, as laboratories lack a reliable and efficient susceptibility test for polymyxin B. The susceptibility rate of polymyxin B reached 96.0%, which is in accordance with results obtained from the United States of America, Europe, Africa and the majority of Asian countries. However, the rate of polymyxin B non-susceptibility (resistant or intermediate) in Singapore is 0.53 (95% confidence interval, 0.12-0.93). In addition, the susceptibility rate of polymyxin B determined via Etest® was not significantly increased compared with that determined via broth microdilution (98.0 vs. 96.0%; P=0.558). Essential and categorical agreement rates reached 98.0%. In conclusion, the polymyxin B resistance rate of CRPA isolates is relatively low in the majority of countries, with the exception of Singapore. Furthermore, Etest® may be a reliable clinical method for the measurement of polymyxin B resistance in CRPA isolates.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, polymyxin B, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, minimal inhibitory concentrations, Etest®, broth microdilution

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) is a gram-negative non-fermenting bacillus that is prevalent in the community and hospital environment. Carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (CRPA) is a major cause of life-threatening infections worldwide (1,2). CRPA is considered to be a multidrug resistant (MDR) pathogen, as it is intrinsically resistant to different types of antimicrobial drugs. CRPA also has the capacity to develop resistance to various antimicrobial agents, thereby reducing the number of available treatment options. In the previous decade, the resistance rate of carbapenem has increased 3-fold in various countries, including the United States of America (USA), Singapore, Brazil, Iran and China, reaching 50-80% in certain areas (3-6). Since the 1950s, polymyxins have been popular for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections (7). However, their use has been restricted, due to significant neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. With an increasing number of CRE infections observed over recent years, polymyxin B and colistin have become increasingly popular treatment choices. Although the resistance rate of polymyxin B is low in most countries, it appears to be increasing. Globally, the polymyxin B resistance rate is <5%; however, it has been reported to be 50% in Singapore. Therefore, clinicians should be vigilant in regards to the rising rate of resistance (3-6, 8). Identifying an appropriate method for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) of polymyxin B and colistin is important for the treatment of CRPA infections.

A reliable method for testing polymyxin susceptibility remains elusive. In 2017, the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute® (CLSI®) no longer considered the disc diffusion (DD) method to be appropriate for colistin susceptibility testing. Furthermore, the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) did not previously deem DD to be an appropriate method for colistin susceptibility testing (9). CLSI and EUCAST guidelines have suggested broth microdilution (BMD) as the reference method for polymyxin B and colistin susceptibility testing (9). However, technical issues have been reported by clinicians worldwide, as polymyxin B and colistin adhere to microtiter plates, contributing to inaccurate results. Therefore, many clinical laboratories have used Etest® strips as an alternative method.

Studies describing the use of Etest® for polymyxin B testing in CRPA are scarce and previous data have disputed the reliability of this method (10,11). In addition, EUCAST has revised the breakpoints for colistin in its guidelines of 2017 and 2018 (9,12). As novel data has been generated over the last two years, it is necessary to compare the Etest® and BMD methods in accordance with CLSI/EUCAST standards in larger CRPA populations. The present study analyzed CRPA resistance to polymyxin B in the Suzhou district of China. A comparison analysis of polymyxin B resistance rates from different countries or regions was also performed to determine resistance trends. Additionally, the present study assessed the effectiveness and reliability of Etest® in a clinical laboratory setting.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolates

A total of 50 non-duplicated clinical CRPA isolates that were non-susceptible (resistant or intermediate) to any carbapenem (imipenem or meropenem) were identified and collected from patients admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, the leading tertiary hospital of Suzhou district with 3,000 beds, between October 2017 and February 2019. All isolates were stored at -80˚C in 10% glycerol and sub-cultured twice prior to testing. Isolates were identified using an automated system (Vitek2 compact; bioMérieux). P. aeruginosa [American Type culture collection (ATCC)® 27853™; 0.5-4 µg/ml] and Escherichia coli (ATCC® 25922™; 0.25-2 µg/ml) served as quality control strains in the 2 susceptibility methods assessed. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University and was performed in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Susceptibility testing

All susceptibility testing was conducted in accordance with the CSLI® recommendations (12). The range of susceptible, resistant and intermediate polymyxin B concentrations were ≤2, ≥8 and 4 µg/ml, respectively. Additionally, the carbapenems that were assessed (imipenem or meropenem) demonstrated the same ranges as polymyxin B (susceptible, ≤2 µg/ml; resistant, ≥8 µg/ml; intermediate, 4 µg/ml). BMD was performed using a cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton II broth (Wenzhou Kangtai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) in accordance with CLSI® guidelines. Each test was duplicated and a third test was performed for discrepant minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) or for MICs exceeding 1 log2 dilution. The polymyxin B Etest® (Wenzhou Kangtai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was performed in the clinical microbiology laboratory in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. The results were compared with those obtained via BMD.

Search strategy

The PubMed and Embase databases updated on April 2019 were searched using the following terms: ‘Pseudomonas aeruginosa’ or ‘Polymyxin B’, together with ‘antimicrobial resistance’. Entire manuscripts associated with the resistance rate of polymyxin B and P. aeruginosa infection were then identified.

Selection of literature

The titles and abstracts of previous studies obtained from PubMed and Embase were reviewed. If the titles appeared to be associated with the research strategy abstracts were reviewed. If abstracts correlated with the research strategy the full texts were reviewed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) An original article or research article; ii) short communications; and iii) correspondence or letters. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Reviews or case reports; and ii) animal experiments.

Statistical analysis

The present study utilized CLSI® susceptibility breakpoints in CRPA isolates to obtain all descriptive statistics including susceptibility (%), resistance (%), the MIC90 concentration (mg/l) and the range (mg/l). Essential agreement (EA) was defined as samples with MICs that were equivalent to the ± 1-log2 dilution between the polymyxin B Etest® methodology and the reference method. A result was deemed inconsistent if there was a difference of ± 2-log2 in the dilution of results. Categorical agreement (CA) was determined if the results from both methods belonged to the same category of susceptibility. A serious major error rate was defined as the percentage of CRPA isolates reported to be susceptible using the Etest® method, but resistant when using the reference method (false susceptibility). A major error rate was defined as the percentage of CRPA isolates reported to be resistant using the Etest® method, but susceptible using the reference method (false resistance). Finally, a minor error rate was determined if acceptable levels were defined as <1.5% for very major errors, <3% for major errors and <10% for minor errors, all of which were indicated in the CLSI® document M23-A2(9). The odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) were determined to evaluate the association power. The χ2 test-based Q-statistic and I2 statistics were also utilized as previously described (13,14). If there was no evident heterogeneity, the fixed-effects model was applied (15). If there was heterogeneity, a random-effects model was utilized (16). All statistics were performed using Stata software (v.14.0; StataCorp LLC).

Results

Bacterial isolates

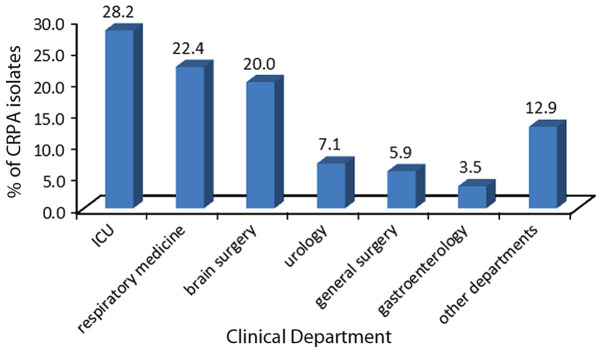

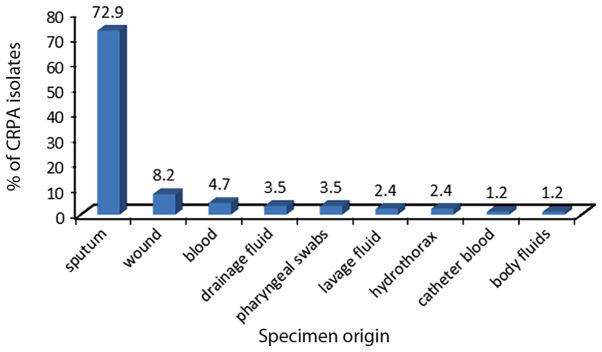

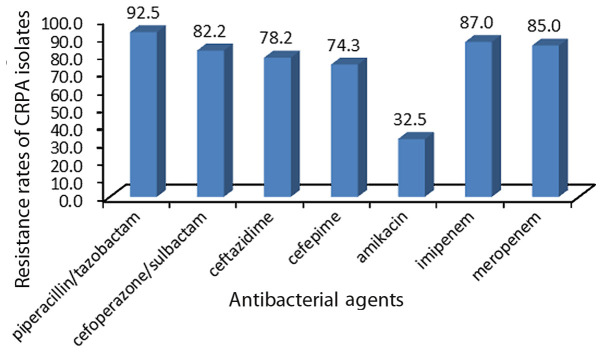

In total, 50 CRPA clinical isolates were collected from the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University. The isolates were obtained from different clinical departments and specimen types (Figs. 1 and 2), and were determined to be non-susceptible to imipenem or meropenem. Fig. 3 presents the resistance rate of CRPA isolates to several antibacterial agents.

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from different clinical departments of the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University. ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University by specimen type.

Figure 3.

Resistance rates of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University to several crucial antibacterial agents. Y-axis is the percentage of different antibacterial agents.

EA and CA

Following BMD, only 2 isolates were determined to be non-susceptible to polymyxin B according to CLSI® criteria (both 4.0 mg/l). The susceptibility rate reached 96.0 and 98.0%, as determined via BMD and Etest® methods, respectively. The EA and CA reached 98.0%. No very major or major errors were detected in the 50 CRPA strains. Furthermore, only 2.0% minor errors were detected (Tables I and II). The detailed results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing are provided in Table III.

Table I.

MIC comparison analysis between Etest® and BMD.

| Variable | MIC50 (mg/l) | MIC90 (mg/l) | Range (mg/l) | Susceptible (%) | Non-susceptible (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMD | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5-4.0 | 96.0 | 4.0 |

| Etest® | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5-2.0 | 98.0 | 2.0 |

BMD, broth microdilution; MIC50, 50% minimal inhibitory concentration; MIC90, 90% minimal inhibitory concentration.

Table II.

EA and CA comparison analysis between Etest® and BMD.

| Comparison | EA | CA | Very major error (%) | Major error (%) | Minor error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMD vs. Etest® | 98.0 | 98.0 | 0 | 0 | 2.0 |

BMD, broth microdilution; EA, essential agreement; CA, category agreement.

Table III.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Etest® and BMD from carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosaisolates.

| Antimicrobial susceptibility testing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of isolates | IPM | MEM | PB (Etest®) | PB (BMD) |

| Pae-503 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-504 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-505 | Resistant | Intermediate | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-506 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-507 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-510 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-511 | Resistant | Intermediate | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-512 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Pae-514 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-515 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-516 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-517 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-518 | Resistant | Resistant | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Pae-520 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-521 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-522 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-523 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-524 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-525 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-526 | Resistant | Intermediate | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-529 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Pae-531 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-532 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-533 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-534 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-535 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-536 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-537 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| Pae-538 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-539 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-540 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Pae-541 | Resistant | Resistant | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Pae-542 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Pae-555 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Pae-561 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-562 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Pae-565 | Resistant | Intermediate | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Pae-566 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-567 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-568 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Pae-569 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Pae-571 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Pae-572 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-573 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Pae-574 | Resistant | Resistant | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-575 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-576 | Resistant | Resistant | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Pae-578 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-579 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Pae-580 | Resistant | Resistant | 2.0 | 1.0 |

BMD, broth microdilution; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; Pae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; PB, polymyxin B.

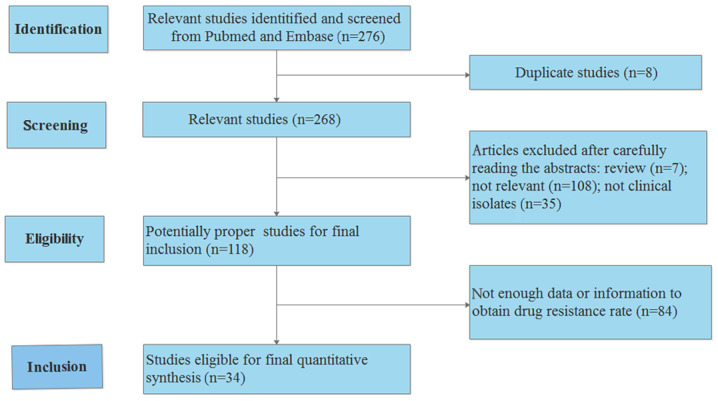

A total of 34 previous studies assessing the resistance rate of polymyxin B in P. aeruginosa were reviewed and analyzed (Table IV) (4-6,8,17-46). The process used to search the literature is presented in Fig. 4. The results revealed that the resistance rate of polymyxin B was relatively low in the majority of countries and regions, with the exception of Singapore. The resistance rate of polymyxin B in Singapore reached 53% (95% CI, 12-93%). A summary of the susceptibility analyses in different countries or regions is presented in Table V.

Table IV.

Detailed literature review of data obtained from various countries or regions.

| First author | Year (ref) | Country/district | Number of isolates | Method | Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landman | 2005(10) | USA | 527 | AD | 36.0 |

| Yang | 2005(18) | China | 320 | AD | 20.6 |

| Kirby | 2006(19) | USA | 351 | BMD | 8.0 |

| Gales (a) | 2006(4) | North America | 3,036 | BMD | 12.5 |

| Gales (b) | 2006(4) | Latin America | 1,626 | BMD | 12.5 |

| Gales (c) | 2006(4) | Europe | 3,145 | BMD | 12.5 |

| Gales (d) | 2006(4) | Asia-Pacific | 898 | BMD | 12.5 |

| van der Heijden | 2007(20) | Brazil | 109 | Etest® | 0.0 |

| Raja | 2007(21) | Malaysia | 505 | DD | 9.9 |

| Tan | 2008(22) | Singapore | 188 | BMD | 17.6 |

| Scheffer | 2010(23) | Brazil | 29 | AD | 100.0 |

| Tam | 2010(24) | USA | 18 | Etest® | 100.0 |

| Cereda | 2011(25) | Brazil | 94 | BMD | 44.1 |

| Lim | 2011(8) | Singapore | 22 | BMD | 100.0 |

| Memish | 2012(27) | Saudi Arabia | 1,734 | DD | 15.9 |

| Haeili | 2013(28) | Iran | 112 | DD | 50.0 |

| YN Liu | 2012(26) | China | 82 | AD | 74.4 |

| Qi Wang | 2013(21) | China | 178 | AD | 28.7 |

| Xiao | 2013(30) | China | 16 | BMD | 25.0 |

| Ameen | 2015(32) | Pakistan | 230 | DD | 49.5 |

| Ali | 2015(31) | Pakistan | 204 | DD | 22.0 |

| Kim | 2015(39) | South Korea | 100 | BMD | NR |

| Vaez | 2015(5) | Iran | 45 | DD | 100.0 |

| Habibi | 2015(33) | Iran | 8 | DD | 12.5 |

| Bangera | 2015(36) | India | 224 | DD | 7.14 |

| Qi Wang | 2015(34) | China | 201 | AD | 28.9 |

| Zhang | 2015(35) | China | 42 | BMD | 79.0 |

| Yang | 2015(18) | China | 256 | DD | 34.4 |

| Zowalaty | 2016(37) | Qatar | 86 | AD | 1.1 |

| Gong | 2016(38) | China | 43 | DD | 61.5 |

| Grewal | 2017(40) | India | 190 | DD | 16.3 |

| Wilhelm | 2018(6) | Brazil | 6 | BMD | 100.0 |

| Sader (a) | 2018(45) | USA | 417 | BMD | 13.9 |

| Sader (b) | 2018(45) | Europe | 491 | BMD | 19.3 |

| Sader (c) | 2018(45) | China | 311 | BMD | 22.2 |

| Ismail | 2018(43) | Iraq | 22 | DD | 22.7 |

| Azimi | 2018(41) | Iran | 160 | DD | 98.8 |

| Dogonchi | 2018(42) | Iran | 71 | DD | 28.2 |

| Kuti | 2018(44) | China | 112 | AD | 40.2 |

BMD, broth microdilution; AD, agar-dilution; DD, disk diffusion; USA, United States of America; (a-d), different studies conducted by the same author.

Figure 4.

Search process used for the comparison analysis performed in the present study.

Table V.

Overall analysis of susceptibility trends in different countries or districts.

| Country or region | Non-susceptibility (95% CI) | Weight (%) |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 0.03 (0.02-0.04) | 17.17 |

| China | 0.01 (0.01-0.02) | 26.10 |

| Latin America | 0.01 (0.01-0.02) | 12.36 |

| Europe | 0.01 (0.01-0.02) | 8.70 |

| Malaysia | 0.01 (0.00-0.02) | 4.16 |

| Singapore | 0.53 (0.12-0.93) | 0.68 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.02 (0.02-0.03) | 4.33 |

| Iran | 0.05 (0.01-0.09) | 6.83 |

| Pakistan | 0.07 (0.01-0.18) | 4.49 |

| South Korea | 0.06 (0.01-0.11) | 1.08 |

| India | 0.01 (0.00-0.02) | 7.25 |

| Qatar | 0.01 (0.00-0.03) | 2.77 |

| Iraq | 0.14 (0.01-0.28) | 0.14 |

CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

The issue of limited treatment options for CRPA has attracted increasing attention in the previous decade. Despite the neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity generated by polymyxin B, it remains a viable treatment option to which the majority of CRPA strains remain susceptible (47). However, the resistance rates of antibacterial agents may differ between geographical locations; for example, the resistance rate of polymyxin B is relatively low in the majority of countries and regions, with the exception of Singapore, whose resistance rate has been reported to be as high as 53% (95% CI, 12-93%). Polymyxin B resistance depends on a complicated multi-factorial process that includes polymyxin B exposure, the inappropriate usage of other antibacterial agents, such as carbapenems, and resistance to transmission via plasmids (48). The high resistance rates observed in Singapore may be due to the early usage of polymyxin B in the late 1990 s, which was earlier than the majority of countries and regions globally (22). In addition, polymyxin B is used as the primary polymyxin for the treatment of multidrug-resistant gram-negative infections (22). Locally, the combination of polymyxin B and other antibiotics for the treatment of infections is also common (22). Polymyxin B is rarely administered in the USA, Europe, Africa and Asia for several reasons: i) Physicians in the USA and Europe frequently use polymyxin E to treat patients with CRPA; ii) polymyxin B is only used in Brooklyn and New York city; iii) The majority of Asian countries, including China, have not approved the prescription and sale of polymyxin B (49,50).

The meta-analysis in the present study offers important data regarding the trends in CRPA resistance to polymyxin B in different global regions. Generally, the susceptibility rate of polymyxin B is high in most countries. However, an efficient and reliable method of antibiotic susceptibility testing for polymyxin B has yet to be established. There are several concerns regarding polymyxin B and colistin in vitro susceptibility testing. Firstly, and primarily, conflicting data regarding the AST procedure exists in the literature (12). Secondly, it is not clear which reference method is the most appropriate for making comparisons (51). Thirdly, the testing population that represents the MIC spectrum of polymyxin (highly resistant or highly sensitive) is restricted and inaccessible (51). Fourthly, it is difficult to obtain reproducible susceptibility information due to the heteroresistance exhibited within bacterial isolates (52). Finally, despite the MICs obtained in the present study, a single value may not accurately represent the populations that exhibit heteroresistance.

It has been demonstrated that DD is not a reliable method for susceptibility testing, and the CLSI® and EUCAST do not recommended it for polymyxin B testing (53,54). Although BMD has been recommended as a reference method by the CLSI® and EUCAST, it is time-consuming and laborious procedure, which represents a burden in routine clinical practices. In recent years, the majority of studies have focused their attention on the effectiveness and reliability of Etest® (10,20). However, certain issues remain unresolved. Studies comparing the MIC of Etest® with BMD in CRPA are rare. In addition, there are uncertainties and contrasting opinions surrounding the reliability of the Etest® method. Simar et al (10) demonstrated that the Etest® was not a reliable method for the detection of the polymyxin B MIC in CRPA strains. A high inconsistency rate between polymyxin B Etest® and BMD MICs was also revealed. Additionally, van der Heijden et al (20) revealed that only 1.2% of very major errors were detected and no major errors were determined. However, 48.7% of minor errors were detected, with the EA reaching 61%. It is well known that the acceptable rate of EA and minor errors should be ≥90 and ≤10%, respectively. In the present study, almost no difference was detected between the Etest® and BMD, as the EA reached 98.0%. No very major errors or major errors were identified, and only 2.0% minor errors were detected. All of the measurable indicators including EA, CA, very major errors, major errors and minor errors were within the acceptable level. Despite similarities in the aims and techniques utilized in a previous study by van der Heijden et al (20), the present study was valuable, as few studies have performed methodological comparisons between BMD and Etest® testing methods for polymyxin B. Furthermore, the breakpoint of polymyxin B MIC antibiotic susceptibility tests was updated in the 2017 edition of the CLSI® (12). As new data have been generated in the past decade, it is necessary to compare the Etest® with BMD methods using the new CLSI/EUCAST standards for CRPA strains.

The results of the present study differ to those published previously. There are several reasons that may account for this. Firstly, Western countries began administering polymyxins earlier than Asian countries. In 2003, it was reported that at least nine P. aeruginosa isolates were non-susceptible to colistin in Greece (55). Furthermore, in 2005, a marked decrease in polymyxin susceptibility was detected in Brooklyn and New York city, in the USA (17). However, polymyxins have not been employed by clinical physicians in China. The resurgence of polymyxin use in Malaysia occurred in 2009 due to the lack of effective treatment options for MDR gram-negative superbugs (56). Therefore, the sensitivity rate of polymyxins for CRPA in Asian countries has been identified to be increased compared with Western countries. The results of the present study may differ from previous studies due to the resistance mechanisms utilized. For example, Tan et al (53) identified the activity of mobilized colistin resistance (mcr-1), which was a resistance gene in the majority of polymyxin-resistant enterobacteriaceae isolates, but this was not observed in the study by Rojas et al (57). The present study did not investigate mcr-1 and it was challenging to elucidate the resistant mechanisms utilized by polymyxins. At present, the PhoPQ regulatory system is the only mechanism considered to serve an important role in polymyxin resistance (58). Heteroresistance may also have had a significant effect on the results of the present study. Heteroresistance occurs when sensitized bacteria are mixed with a small drug-resistant subpopulation, leading to the unexplained failure of clinical treatment. Heteroresistance is affected by diverse factors including bacteria species, antibacterial agents, resistance phenotypes or mechanisms and local epidemiology (59-61). The present study hypothesized that the discrepancy between BMD and Etest® results may be explained by the fact that BMD is more sensitive to heteroresistant subpopulations than Etest®. However, a small number of heteroresistant colonies growing in the inhibition zone appeared to contribute to the results of the Etest® strip. If equal quantities of heteroresistant and sensitive colonies grew in the specific microtiter wells and turned the wells turbid, then an elevated MIC of polymyxin B would be recorded. Furthermore, the degree of heteroresistance may determine the very major errors, major errors and minor errors between the present study and previous studies. However, studies that assess heteroresistance are scarce and rarely investigate polymyxin B in P. aeruginosa (62).

The identification of feasible and reliable susceptibility testing methods to determine the MIC of polymyxin B are urgently required. The results of the present study identified a good concordance between BMD and Etest®. However, there are certain limitations: The present study is single-center investigation and does not contain genetic data regarding the resistant mechanisms utilized by polymyxins. Furthermore, the CRPA populations in the present study lacked isolates with an MIC of polymyxin B>2 mg/l (n=1). Additionally, detailed information regarding clinical outcome data was not obtained.

Despite the existence of several studies from various geographical regions assessing trends of polymyxin B in the antimicrobial resistance of CRPA, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first that provides global data and compares the MIC of Etest® with BMD for CRPA isolates in China. In conclusion, polymyxin B resistance rates are relatively low in the majority of countries and regions, with the exception of Singapore. The Etest® may serve as a potentially reliable clinical method of polymyxin B MIC determination in CRPA.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms Li Yan (Zhangjiagang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine) and Mr Haitao Hu (People's Hospital of Taizhou) who assisted in the collection and organization of the experiment data.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BK20170364), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81702065) and Jiangsu Province Medical Innovation Team (grant no. CXTDB2017009).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

LZ and XC conceived and designed the experiments of the current study. XC, QZ, YR and JX performed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents, materials and analysis tools, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and informed consent

Patient data were collected retrospectively from electronic health records. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University and was in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The patients provided written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

The patients provided written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Khosravi AD, Shafie F, Abbasi Montazeri E, Rostami S. The frequency of genes encoding exotoxin A and exoenzyme S in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients. Burns. 2016;42:1116–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leseva M, Arguirova M, Nashev D, Zamfirova E, Hadzhyiski O. Nosocomial infections in burn patients: Etiology, antimicrobial resistance, means to control. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2013;26:5–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu PY, Sun YX, Gu DQ, Cheng JL. Drug resistance of imipenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli in coal worker's pneumoconiosis chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with lower respiratory tract infection. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2013;31:700–702. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gales AC, Jones RN, Sader HS. Global assessment of the antimicrobial activity of polymyxin B against 54 731 clinical isolates of Gram-negative bacilli: Report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance programme (2001-2004) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:315–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaez H, Moghim S, Nasr Esfahani B, Ghasemian Safaei H. Clonal relatedness among imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from ICU-hospitalized patients. Crit Care Res Pract. 2015;2015(983207) doi: 10.1155/2015/983207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilhelm CM, Nunes LS, Martins AF, Barth AL. In vitro antimicrobial activity of imipenem plus amikacin or polymyxin B against carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;92:152–154. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nation RL, Velkov T, Li J. Colistin and polymyxin B: Peas in a pod, or chalk and cheese? Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:88–94. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim TP, Lee W, Tan TY, Sasikala S, Teo J, Hsu LY, Tan TT, Syahidah N, Kwa AL. Effective antibiotics in combination against extreme drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa with decreased susceptibility to polymyxin B. PLoS One. 2011;6(e28177) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakthavatchalam YD, Veeraraghavan B. Challenges, issues and warnings from CLSI and EUCAST working group on polymyxin susceptibility testing. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:DL03–DL04. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/27182.10375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simar S, Sibley D, Ashcraft D, Pankey G. Colistin and polymyxin B minimal inhibitory concentrations determined by Etest found unreliable for Gram-negative bacilli. Ochsner J. 2017;17:239–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nhung PH, Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Phuong DM, Shimada K, Anh NQ, Binh NG, Thanh do V, Ohmagari N, Kirikae T. Evaluation of the Etest method for detecting colistin susceptibility of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative isolates in Vietnam. J Infect Chemother. 2015;21:617–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulengowski B, Ribes JA, Burgess DS. Polymyxin B Etest® compared with gold-standard broth microdilution in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae exhibiting a wide range of polymyxin B MICs. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landman D, Bratu S, Alam M, Quale J. Citywide emergence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains with reduced susceptibility to polymyxin B. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:954–957. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang QW, Xu YC, Chen MJ, Hu YJ, Ni YX, Sun JY, Yu YS, Kong HS, He L, Wu WY, et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance among nosocomial gram-negative pathogens from 15 teaching hospitals in China in 2005. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;87:2753–2758. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirby JT, Fritsche TR, Jones RN. Influence of patient age on the frequency of occurrence and antimicrobial resistance patterns of isolates from hematology/oncology patients: Report from the chemotherapy alliance for neutropenics and the control of emerging resistance program (North America) Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;56:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Heijden IM, Levin AS, De Pedri EH, Fung L, Rossi F, Duboc G, Barone AA, Costa SF. Comparison of disc diffusion, Etest and broth microdilution for testing susceptibility of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa to polymyxins. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2007;6(8) doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raja NS, Singh NN. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a tertiary care hospital. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40:45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan TY, Hsu LY, Koh TH, Ng LS, Tee NW, Krishnan P, Lin RT, Jureen R. Antibiotic resistance in gram-negative bacilli: A Singapore perspective. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:819–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheffer MC, Bazzo ML, Steindel M, Darini AL, Climaco E, Dalla-Costa LM. Intrahospital spread of carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a university hospital in Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010;43:367–371. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822010000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tam VH, Chang KT, Abdelraouf K, Brioso CG, Ameka M, McCaskey LA, Weston JS, Caeiro JP, Garey KW. Prevalence, resistance, mechanisms and susceptibility of multidrug-resistant bloodstream isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1160–1164. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01446-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cereda RF, Azevedo HD, Girardello R, Xavier DE, Gales AC. Antimicrobial activity of ceftobiprole against gram-negative and gram-positive pathogens: Results from INVITA-A-CEFTO Brazilian study. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15:339–348. INVITA-A-CEFTO Brazilian Study Group. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu YN, Cao B, Wang H, Chen LA, She DY, Zhao TM, Liang ZX, Sun TY, Li YM, Tong ZH, et al. Adult hospital acquired pneumonia: a multicenter study on microbiology and clinical characteristics of patients from 9 Chinese cities. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2012;35:739–746. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Memish ZA, Shibl AM, Kambal AM, Ohaly YA, Ishaq A, Livermore DM. Antimicrobial resistance among non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria in Saudi Arabia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1701–1705. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haeili M, Ghodousi A, Nomanpour B, Omrani M, Feizabadi MM. Drug resistance patterns of bacteria isolated from patients with nosocomial pneumonia at Tehran hospitals during 2009-2011. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:312–317. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Zhao CJ, Wang H, Yu YS, Zhu ZH, Chu YZ, Sun ZY, Hu ZD, Xu XL, Liao K, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Gram-negative bacilli isolated from 13 teaching hospitals across China. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013;93:1388–1396. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao H, Ye X, Liu Q, Li L. Antibiotic susceptibility and genotype patterns of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from mechanical ventilation-associated pneumonia in intensive care units. Biomed Rep. 2013;1:589–593. doi: 10.3892/br.2013.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali Z, Mumtaz N, Naz SA, Jabeen N, Shafique M. Multi-drug resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa: a threat of nosocomial infections in tertiary care hospitals. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ameen N, Memon Z, Shaheen S, Fatima G, Ahmed F. Imipenem Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: The fall of the final quarterback. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31:561–565. doi: 10.12669/pjms.313.7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Habibi A, Honarmand R. Profile of Virulence Factors in the Multi-Drug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Strains of Human Urinary Tract Infections (UTI) Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2015;17(e26095) doi: 10.5812/ircmj.26095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Wang Q, Wang H, Yu Y, Xu X, Sun Z, Lu J, Yang B, Zhang L, Hu Z, Feng X, et al. Antimicrobial resistance monitoring of gram-negative bacilli isolated from 15 teaching hospitals in 2014 in China. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2015;54:837–845. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang JF, Zhu HY, Sun YW, Liu W, Huo YM, Liu DJ, Li J, Hua R. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection after pancreatoduodenectomy: risk factors and clinic impacts. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2015;16:769–774. doi: 10.1089/sur.2015.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bangera D, Shenoy SM, Saldanha DR. Clinico-microbiological study of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in wound infections and the detection of metallo-β-lactamase production. Int Wound J. 2016;13:1299–1302. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Zowalaty ME, Gyetvai B. Effectiveness of Antipseudomonal Antibiotics and Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pol J Microbiol. 2016;65:23–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gong YL, Yang ZC, Yin SP, Liu MX, Zhang C, Luo XQ, Peng YZ. Analysis of the pathogenic characteristics of 162 severely burned patients with bloodstream infection. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2016;32:529–535. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1009-2587.2016.09.004. (In Chinese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim YH. Conditional probability analysis of multidrug resistance in Gram-negative bacilli isolated from tertiary medical institutions in South Korea during 1999-2009. J Microbiol. 2016;54:50–56. doi: 10.1007/s12275-016-5579-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grewal US, Bakshi R, Walia G, Shah PR. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of non-fermenting gram-negative Bacilli at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Patiala, India. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2017;24:121–125. doi: 10.4103/npmj.npmj_76_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azimi A, Peymani A, Pour PK. Phenotypic and molecular detection of metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with burns in Tehran, Iran. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2018;51:610–615. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0174-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dogonchi AA, Ghaemi EA, Ardebili A, Yazdansetad S, Pournajaf A. Metallo-β-lactamase-mediated resistance among clinical carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in northern Iran: A potential threat to clinical therapeutics. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018;30:90–96. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_101_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ismail SJ, Mahmoud SS. First detection of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases variants (NDM-1, NDM-2) among Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from Iraqi hospitals. Iran J Microbiol. 2018;10:98–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuti JL, Wang Q, Chen H, Li H, Wang H, Nicolau DP. Defining the potency of amikacin against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii derived from Chinese hospitals using CLSI and inhalation-based breakpoints. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:783–790. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S161636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sader HS, Dale GE, Rhomberg PR, Flamm RK. Antimicrobial Activity of Murepavadin Tested against Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the United States, Europe, and China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62: pii:e00311–18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00311-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang X, Xing B, Liang C, Ye Z, Zhang Y. Prevalence and fluoroquinolone resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a hospital of South China. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:1386–1390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meletis G, Skoura L. Polymyxin Resistance Mechanisms: From Intrinsic Resistance to Mcr Genes. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2018;13:198–206. doi: 10.2174/1574891X14666181126142704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teo JQ, Chang CW, Leck H, Tang CY, Lee SJ, Cai Y, Ong RT, Koh TH, Tan TT, Kwa AL. Risk factors and outcomes associated with the isolation of polymyxin B and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae spp.: A case-control study. Antimicrob Agents. 2019;53:657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhan Y, Ma N, Liu R, Wang N, Zhang T, He L. Polymyxin B and polymyxin E induce anaphylactoid response through mediation of Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor X2. Chem Biol Interact. 2019;308:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li S, Jia X, Li C, Zou H, Liu H, Guo Y, Zhang L. Carbapenem-resistant and cephalosporin-susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a notable phenotype in patients with bacteremia. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:1225–1235. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S174876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Humphries RM, Hindler JA. Emerging Resistance, New Antimicrobial Agents ... but No Tests! The Challenge of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing in the Current US Regulatory Landscape. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:83–88. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meletis G, Tzampaz E, Sianou E, Tzavaras I, Sofianou D. Colistin heteroresistance in carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:946–947. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan TY, Ng LS. Comparison of three standardized disc susceptibility testing methods for colistin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:864–867. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gales AC, Reis AO, Jones RN. Contemporary assessment of antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods for polymyxin B and colist in: review of available interpretative criteria and quality control guidelines. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:183–190. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.183-190.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Sambatakou H, Galani I, Giamarellou H. In vitro interaction of colistin and rifampin on multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Chemother. 2003;15:235–238. doi: 10.1179/joc.2003.15.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zakuan ZD, Suresh K. Rational use of intravenous polymyxin B and colistin: A review. Med J Malaysia. 2018;73:351–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rojas LJ, Salim M, Cober E, Richter SS, Perez F, Salata RA, Kalayjian RC, Watkins RR, Marshall S, Rudin SD, et al. Colistin Resistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Laboratory Detection and Impact on Mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:711–718. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee JY, Ko KS. Mutations and expression of PmrAB and PhoPQ related with colistin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamazumi T, Pfaller MA, Messer SA, Houston AK, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, Furuta I, Jones RN. Characterization of heteroresistance to fluconazole among clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:267–272. doi: 10.1128/jcm.41.1.267-272.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Plipat N, Livni G, Bertram H, Thomson RB Jr. Unstable vancomycin heteroresistance is common among clinical isolates of methiciliin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2494–2496. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.5.2494-2496.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomasz A, Nachman S, Leaf H. Stable classes of phenotypic expression in methicillin-resistant clinical isolates of staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:124–129. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.1.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hermes DM, Pormann Pitt C, Lutz L, Teixeira AB, Ribeiro VB, Netto B, Martins AF, Zavascki AP, Barth AL. Evaluation of heteroresistance to polymyxin B among carbapenem-susceptible and -resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1184–1189. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.059220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.