Abstract

Background

Cystic fibrosis is an inherited life‐limiting disorder, characterised by pulmonary infections and thick airway secretions. Chest physiotherapy has been integral to clinical management in facilitating removal of airway secretions. Conventional chest physiotherapy techniques (CCPT) have depended upon assistance during treatments, while more contemporary airway clearance techniques are self‐administered, facilitating independence and flexibility.

Objectives

To compare CCPT with other airway clearance techniques in terms of their effects on respiratory function, individual preference, adherence, quality of life and other outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group Trials Register which comprises references identified from comprehensive electronic database searches and handsearching of relevant journals and conference proceedings. We also searched CINAHL from 1982 to 2002 and AMED from 1985 to 2002.

Date of most recent search: 01 September 2008.

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised clinical trials including those with a cross‐over design where CCPT was compared with other airway clearance techniques. Studies of less than seven days duration were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors allocated quality scores to relevant studies and independently extracted data. If we were unable to extract data, we invited authors to submit their data. We excluded studies from meta‐analysis when data were lost or study design precluded comparison. For some continuous outcomes, we used the generic inverse variance method for meta‐analysis of data from cross‐over trials and data from parallel‐designed trials were incorporated for comparison. We also examined efficacy of specific techniques and effects of treatment duration.

Main results

We identified 83 publications and 29 were included, representing 15 data sets (475 participants). There was insufficient evidence to confirm or exclude any differences, between CCPT and other airway clearance techniques in terms of respiratory function measured by standard lung function tests. Studies undertaken during acute exacerbations demonstrated relatively large gains in respiratory function irrespective of airway clearance technique. Longer‐term studies demonstrated smaller improvements or deterioration over time. Ten studies reported individual preferences for technique, with participants tending to favour self‐administered techniques. Heterogeneity in the measurement of preference precluded these data from meta‐analysis.

Authors' conclusions

This review was unable to demonstrate any advantage of CCPT over other airway clearance techniques in terms of respiratory function, but this may have reflected insufficient evidence rather than real equivalence between methods. There was a trend for participants to prefer self‐administered airway clearance techniques. Limitations of this review included a paucity of well‐designed, adequately‐powered, long‐term trials.

Plain language summary

A comparison of usual chest physiotherapy to other methods of airway clearance in people with cystic fibrosis

Excess mucus is produced in the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis. This leads to recurrent infection and tissue damage. It is important to clear this mucus using drugs and various chest physiotherapy techniques. We aimed to compare the effects of different methods on lung function and patient preference. We looked for studies lasting over one week. We included fifteen studies in the review. These studies did not show any difference between chest physiotherapy and other therapies in terms of lung function. Studies of acute infections showed improved lung function irrespective of type of treatment. Longer‐term studies showed smaller improvements or decline. In ten studies participants preferred techniques they administered on themselves. The review was limited by the lack of well‐designed long‐term trials. We did not find evidence that conventional chest physiotherapy techniques were any better than other treatments for lung function. We can not recommend any single treatment over another at this time.

Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a common inherited life‐limiting disorder. Persistent infection and inflammation within the lungs are the major contributory factors to severe airway damage and loss of respiratory function over the years (Cantin 1995; Konstan 1997). Continuous production of thick secretions leads to airway obstruction and mucus plugging (Zach 1990). Removal of airway secretions is therefore an integral part of the management of CF. A variety of methods are used to help remove secretions from the lungs, some physical (for example chest physiotherapy) and some chemical (for example medications and inhalation therapies). Treatment methods which improve secretion clearance are considered essential in optimising respiratory status and reducing the progression of lung disease. Chest physiotherapy plays an important role in assisting the clearance of airway secretions and is usually commenced as soon as the diagnosis of CF is made.

Conventional chest physiotherapy (CCPT) techniques frequently involve the assistance of another person such as a physiotherapist, parent or caregiver. The techniques may include postural drainage, percussion and vibration, huffing and coughing.

More recently several self‐administered airway clearance techniques (ACTs) have been developed. These include the active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT), forced expiration technique (FET), autogenic drainage (AD), positive expiratory pressure (PEP), flutter, high frequency chest compression (HFCC) and exercise. All these methods are defined below. These methods of treatment aim to give the individual more independence and flexibility in clearing their airway secretions. Despite the expansion in number of treatment modalities, there remains little evidence supporting their efficacy (Prasad 1998; van der Schans 1996).

A previous Cochrane review compared any form of chest physiotherapy to no treatment (van der Schans 2000). This included six cross‐over studies, five of which involved single treatment measurements and the remaining study was conducted over two days. Conclusions suggested that ACTs could have short‐term effects in increasing mucus transport, demonstrated by improved mucous expectoration or radioactive clearance. The absence of long‐term studies precluded any conclusions regarding the ongoing effects of ACTs.

Another recently published Cochrane review compared positive expiratory pressure (PEP) physiotherapy with other forms of airway clearance in people with CF (Elkins 2006). Twenty studies met the review inclusion criteria, 16 of which were cross‐over in design and seven of which were single treatment studies. There was insufficient evidence to demonstrate whether PEP was more or less effective than other forms of physiotherapy. There was limited evidence that participants preferred PEP compared to other techniques. Both reviews pointed out the relatively low quality scores achieved by included studies (Elkins 2006; van der Schans 2000).

This review compares CCPT with other ACTs used for airway clearance in people with CF. Subsequent reviews will continue to examine whether specific physiotherapy treatment modalities offer any advantages over others.

Objectives

To determine if CCPT is more effective than other ACTs for people with CF.

To determine the acceptability of CCPT by people with CF compared to other ACTs.

The following hypotheses were tested:

CCPT is more effective than other ACTs in maintaining or improving respiratory function;

CCPT is more acceptable to people with CF than other ACTs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised or quasi‐randomised clinical trials were considered, including those with a cross‐over design.

Studies of less than seven days duration (including single treatment studies) were excluded from analysis in this review.

Types of participants

People with CF, of any age, diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria and sweat testing or genotype analysis.

Types of interventions

CCPT was compared with other ACTs as described below.

In the existing literature and in practical terms, variation occurs in the application of specific techniques. For the purposes of this review, it was necessary to group these variations within broad definitions of the treatment modalities. Separate analysis of variations within each technique would have rendered this review unmanageable.

The following treatment modalities described by the authors to be the primary intervention (with or without additional techniques) were included:

Conventional chest physiotherapy (CCPT)

This included any combination of the following: postural drainage; percussion; chest shaking; huffing; and directed coughing. It did not include the use of exercise, FET, PEP or other mechanical devices.

Positive expiratory pressure (PEP) mask therapy

PEP was defined as breathing with a positive expiratory pressure of 10‐25 cmH20 (with or without additional techniques).

High pressure PEP (hPEP) mask therapy

This is a modification of PEP which includes a full forced expiration against a fixed mechanical resistance (with or without additional techniques).

Active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT)

This comprises relaxation/breathing control, forced expiration technique (FET), thoracic expansion exercises and may include postural drainage or chest clapping.

Autogenic drainage (AD)

This breathing technique uses high expiratory flow rates at varying lung volumes to enhance mucous clearance while avoiding airway closure.

Airway oscillating devices (AOD)

This included flutter / cornet / acapella and intrapulmonary percussive ventilation (IPV). The flutter, cornet and acapella devices produce an oscillatory PEP effect within the airways. Intrapulmonary percussive ventilation provides continuous oscillation to the airways via the mouth.

Mechanical percussive devices (MP) and external high frequency chest compression devices (HFCC)

HFCC devices include the Thairapy Vest and the Hiyak Oscillator which provide external chest wall compression. MP devices provide localised chest wall percussion.

Exercise prescribed for the purpose of airway clearance either independently or as an adjunct to other techniques.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome

1. Pulmonary function: forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1); forced vital capacity (FVC); and forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% (FEF25‐75). These values were obtained in 'percentage predicted' format (age and height corrected) because of the potential for wide variations in participant age groups.

Secondary outcomes

2. Adherence to therapy and individual preference 3. Quality of life measures 4. Number of respiratory exacerbations per year 5. Number of admissions / days in hospital per year 6. Number of courses / days of intravenous antibiotics per year 7. Objective change in exercise tolerance 8. Total lung capacity (TLC) and functional residual capacity (FRC) 9. Mucus transport rate as assessed by radioactive tracer clearance 10. Radiological ventilation scanning 11. Oxygen saturation measured by pulse or transcutaneous oximetry 12. Cost / benefit analysis of intervention 13. Nutritional status as assessed by growth, weight and body composition 14. Mortality

Additional outcomes which have arisen from the review

15. Adverse events 16. Other outcomes (seeResults)

Expectorated secretions (mucus, sputum, phlegm), dry or wet weight, or volume are usually employed as outcome measures in single treatment studies or those less than seven days duration. Since short‐duration studies were not included in this review, sputum measurement was not included as an outcome parameter.

Search methods for identification of studies

Relevant trials were identified from the Cochrane Group's Cystic Fibrosis trials register using the terms: physiotherapy AND conventional.

This register is compiled from electronic searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Clinical Trials) (updated each new issue), quarterly searches of MEDLINE, a search of EMBASE to 1995 and the prospective hand searching of two journals ‐ Pediatric Pulmonology and the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. Unpublished work was identified by searching the abstract books of the three major cystic fibrosis conferences: the International Cystic Fibrosis conference; the European Cystic Fibrosis conference; and the North American Cystic Fibrosis conference and of the British Thoracic Society meetings, the European Respiratory Society meetings and there American Thoracic Society meetings.

Additional searches of two electronic databases not covered by the Group's search strategy were also undertaken. These were CINAHL from 1982 to 2002 and AMED 1985 to 2002 using the following sets of MeSH search terms:

physical Therapy or Physiotherapy AND Cystic Fibrosis;

physical Therapy Techniques or Physiotherapy Techniques AND Cystic Fibrosis.

Date of the most recent search of the Group's Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register: 01 September 2008.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (EM, AP) independently selected trials to be included in the review. We scored the quality of included studies according to criteria described by Jadad (Jadad 1996). This method allocates five points on the basis of randomisation, double blinding and the description of withdrawals and dropouts. Studies scoring the maximum five points were considered to be of good quality. Studies scoring either zero, one or two points were considered to be of poor quality. Two independent authors categorised the physiotherapeutic interventions independently and allocated a Jadad score of methodological quality. If there was disagreement about whether we should include a study in the review or regarding the Jadad quality score allocated, we asked an independent author from a third centre to review the paper(s) in question.

The two authors extracted data independently on the outcome measures listed above. If we were unable to extract data directly from the publication, we contacted authors and invited them to provide data for inclusion in the meta‐analysis. We made considerable efforts to contact authors to request data. When we made contact, we sent at least two requests for data. If we could not locate authors, or they did not send the data, we placed these studies into a 'Studies awaiting assessment' category for potential inclusion in future updates of this review. Where data were either lost or we could not extract them in the format required, or where study design precluded appropriate comparison, we excluded studies from the meta‐analysis but included them in the review. We used the Cochrane Review Manager software to compile and analyse the data (Review Manager 2003).

For continuous outcomes, we recorded either the mean change from baseline for each group or mean post treatment / intervention values and the standard deviation or standard error for each group. We incorporated data from cross‐over trials into meta‐analysis using the generic inverse variance method, involving expression of data in terms of the paired mean differences between treatments and their standard error. We calculated these values either from paired individual patient data provided by authors, or by calculation of mean differences between interventions and their standard error from means, standard deviations and P values reported in the manuscript (Elbourne 2002). We combined data from parallel‐designed trials with those from cross‐over trials in meta‐analysis. We calculated the standard errors in parallel‐designed trials from the mean differences between treatments and their confidence intervals. We have reported these data in the comparison tables.

Some authors involved with cross‐over trials were able to provide original individual patient data. For the studies where these data were not available, we elected to use a correlation of zero as the most conservative estimate. In future updates of this review, further data and better understanding of average correlations for these outcomes may allow the use of less conservative correlations.

In the case of binary outcomes, in order to allow an intention‐to‐treat analysis, we collected data on the number of participants with each outcome event by allocated treated group irrespective of compliance and whether or not the individual was later thought to be ineligible, or otherwise excluded for treatment, or follow up.

We grouped studies on specific treatment techniques for the purposes of meta‐analysis (for example, all studies of CCPT versus PEP were grouped). This facilitated comparisons between specific ACTs, as well as comparisons with CCPT. For ease of comparison, and to avoid splitting data to the extent that no comparison was feasible, we also grouped some techniques which had similarities, for example, techniques which involved intra‐ or extra‐pulmonary mechanical percussion (mechanical percussion, HFCC and acoustic percussion). In cases where study design incorporated three or more treatment arms (e.g. CCPT versus PEP versus flutter), we entered data in both subgroups so that we could make comparisons between CCPT and each of the other ACTs. We examined the need to perform sensitivity analyses based on the methodological quality of the studies, including and excluding quasi‐randomised studies, however, this was not necessary on data currently included in the review.

In order to investigate the need for further meta‐analyses, we also examined the potential effects of time according to duration of study. We compared studies undertaken during hospital admissions for pulmonary exacerbations (one‐ to three‐week duration) to longer‐term studies during stable disease. We anticipated substantial improvements in respiratory function in hospitalised participants as a result of intensive therapies, unlike results from longer‐term studies undertaken during stable disease. In such studies we anticipated a maintenance or slow decline in pulmonary function. It is possible that certain ACTs, which have optimal efficacy during acute exacerbations, may not be appropriate for maintenance therapy and vice versa.

Results

Description of studies

Results of search

We identified a total of 83 publications as potentially relevant to this review. Of these, we included 29 publications (representing 15 studies) and excluded 38 publications (representing 27 studies). Eleven publications (representing 10 studies) are awaiting assessment.

Included Studies

A total of 29 publications were included which represented 15 sets of original data and 475 participants (Arens 1994; Bauer 1994; Cerny 1989; Costantini 1998; Darbee 1990; Davidson 1992; Gaskin 1998; Homnick 1995; Homnick 1998; Kraig 1995; McIlwaine 1991; McIlwaine 1997; Reisman 1988; Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987). Several data sets were published both as abstracts and journal articles, or as more than one journal article with different lead authors. Where data were published both as an abstract and article, data were extracted from the final publication. The 15 original data sets comprised 10 full publications (Arens 1994; Bauer 1994; Cerny 1989; Costantini 1998; Homnick 1995; Homnick 1998; McIlwaine 1997; Reisman 1988; Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987) and five as abstracts only (Darbee 1990; Davidson 1992; Gaskin 1998; Kraig 1995; McIlwaine 1991). The median sample size was 19.5 participants (range: 5 to 67). Six of these studies were of a randomised cross‐over design (Darbee 1990; Davidson 1992; Kraig 1995; McIlwaine 1991; Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987), while the remainder were randomised parallel‐group controlled trials. In some cases the number of participants included in meta‐analysis exceeded those in the publication, when the study continued beyond the date of publication and authors provided the additional data. Original data were gratefully received from several authors (Arens 1994; Bauer 1994; Cerny 1989; Costantini 1998; Darbee 1990; Davidson 1992; Gaskin 1998 (kindly provided by Dr Tullis); Homnick 1995; Homnick 1998; McIlwaine 1991; McIlwaine 1997; Orlik 2001; Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987).

Four of the 15 included data sets were studies undertaken during acute pulmonary exacerbations and were of roughly 10 to 16 days duration (Arens 1994; Bauer 1994; Cerny 1989; Homnick 1998). Six of the included studies were between one and six months duration (Darbee 1990; Homnick 1995; Kraig 1995; McIlwaine 1991; Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987). The five remaining included studies were conducted over periods of one year or more (Costantini 1998; Davidson 1992; Gaskin 1998; McIlwaine 1997; Reisman 1988). Five studies made no mention of disease severity at entry. Three studies reported participants to have mild to moderate disease at baseline (Gaskin 1998; Reisman 1988; Tyrrell 1986); two moderate to severe disease (Arens 1994; Cerny 1989); and five studies included people with a broad range of baseline lung function scores (Bauer 1994; Davidson 1992; Homnick 1995; Homnick 1998; McIlwaine 1997).

Age of participants was reported in 13 of the 15 studies. Nine studies reported mean age of participants between 9 years and 16 years, while three studies recorded slightly higher mean ages of participants (20 years to 25 years). The participants in the Costantini study, involving a one‐year randomised controlled trial of CCPT versus PEP, were within the first two months of life at recruitment (Costantini 1998). This study uniquely involved an infant population, and selected outcome measures were not comparable to other included studies. It could therefore not be included in the meta‐analysis.

Excluded Studies

Of the studies relevant to this review, 42 publications were excluded, representing 31 sets of original data. Twenty‐four of these were either single treatment studies or of less than seven days duration and were thus excluded. The remaining seven publications were excluded for the reasons now outlined. One study compared CCPT to a 'no treatment' group, thus did not include a valid comparative intervention (Desmond 1983). One study included a withdrawal design (10: 2: 6: months) and data could not be extracted or interpreted (Oberwaldner 1986). One study had to be excluded because participants were not randomised (Orlik 2001). One study was excluded because data had been lost by authors and could not be extracted from the publication (Tonnesen 1984). One study compared CCPT with and without postural drainage and thus did not include a valid comparative intervention (Button 2003). One study included only six participants, including some without CF and relevant data could not be extracted (Hartsell 1978). In one study different music therapy was used for each randomised group as an adjunct to conventional treatment with no relevant outcomes assessed (Grasso 2000).

Studies awaiting assessment

Eleven references to ten studies await assessment since data could not be extracted from publications in the format required for meta‐analysis. Efforts to contact authors, or efforts by the authors to locate data have to date been unsuccessful (Bain 1988; Giles 1996; Gondor 1999; Klig 1989; Steen 1991; Warwick 1991). A further four references to four studies were identified in the search conducted at the beginning of 2004 and will be assessed for eligibility in a future update of the review (Hare 2002; Keller 2001; Orlik 2000; van Hengstum 1988).

Risk of bias in included studies

Two independent authors categorised the physiotherapeutic interventions independently and allocated a score of methodological quality. There was no disagreement between authors in any cases. No studies were double‐blinded which immediately limited the maximal score to three points. Of the 15 data sets included in this systematic review, methodological quality scoring (Jadad 1996) resulted in three studies achieving three points of a maximal five (Homnick 1995; McIlwaine 1997; Reisman 1988) and eight studies achieving only two points (Arens 1994; Bauer 1994; Cerny 1989; Costantini 1998; Gaskin 1998; Homnick 1998; Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987). The four remaining studies were published abstracts and did not include sufficient information to generate a score (Darbee 1990; Davidson 1992; Kraig 1995; McIlwaine 1991).

Although a methodological score of two out of five is very low, these studies remain the current best available evidence within the field and it was considered reasonable to include them. It is not feasible in many cases for physiotherapists to incorporate blinding into study design, since participants are perfectly aware of the treatment they are receiving. The Jadad system and similar validated scoring systems are therefore a disadvantage to studies of this nature, and low scores are inevitable, since two out of five points are allocated for blinding (Jadad 1996).

Effects of interventions

Fifteen studies involving 475 participants were included in this review (Arens 1994; Bauer 1994; Cerny 1989; Costantini 1998; Darbee 1990; Davidson 1992; Gaskin 1998; Homnick 1995; Homnick 1998; Kraig 1995; McIlwaine 1991; McIlwaine 1997; Reisman 1988; Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987).

Primary outcomes

1. Pulmonary function

Values for the following were expressed as 'percentage predicted': forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1); forced vital capacity (FVC); forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% expired FVC (FEF25‐75).

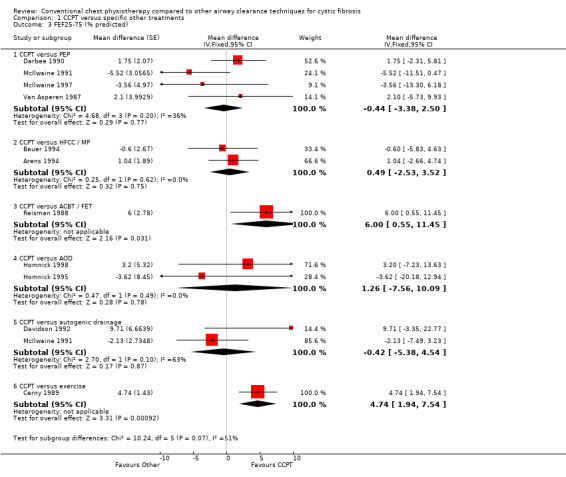

Fourteen studies had data appropriate for meta‐analysis of respiratory function comparing CCPT to other ACTs. The remaining study involved a neonatal population, in whom lung function measurements were not undertaken (Costantini 1998). Meta‐analysis of 14 studies involved 15 data set comparisons, since one study compared CCPT with both PEP and AD (McIlwaine 1991).

CCPT versus PEP

Six pulmonary function data sets comparing CCPT with PEP (164 participants) were included in meta‐analysis (Darbee 1990; Gaskin 1998; McIlwaine 1991; McIlwaine 1997; Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987). No overall group differences between CCPT or PEP were demonstrated in terms of FEV1, mean difference (MD) ‐0.08 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐1.45 to 1.62); FVC, MD 0.38 (95% CI ‐1.56 to 2.33); or FEF25‐75%, MD ‐0.44 (95% CI ‐3.38 to 2.50). Two studies demonstrated significant but divergent differences between CCPT and PEP. One of these studies (16 participants, eight weeks duration), showed significantly greater improvement in the CCPT group than the PEP group in terms of FEV1; and also showed improvements in FVC approaching significance (Tyrrell 1986). By contrast, another study (36 participants, 12 months duration) showed significantly greater improvements in the PEP group than the CCPT group in terms of both FEV1 and FVC (McIlwaine 1997). Duration of data collection in all studies varied between four weeks and two years and visual examination of the data plots indicated no associated effect of time.

CCPT versus HFCC / MP

Three studies compared CCPT with therapies involving extra‐pulmonary mechanical percussion (145 participants). These therapies included HFCC (Arens 1994), mechanical percussion (Bauer 1994) and acoustic percussion (Kraig 1995). Due to their similarities in applied mechanical percussion, they were grouped for meta‐analysis. Two studies were conducted during two‐week hospitalisations for exacerbation (Arens 1994; Bauer 1994), while the other was conducted over two months (Kraig 1995). There were no overall group differences between CCPT or extra‐pulmonary percussive therapies in terms of FEV1, MD ‐1.76 (95% CI ‐4.67 to 1.16); FVC, MD ‐1.42 (95% CI ‐5.17 to 2.33); or FEF25‐75%, MD 0.49 (95% CI ‐2.53 to 3.52). All three publications concluded that there were no significant differences between CCPT and extra‐pulmonary percussive therapies. The RevMan meta‐analysis of this data showed considerable heterogeneity in FVC changes following CCPT or HFCC in all three studies. There appeared to be no associated effect of time for FEV1, FVC or FEF25‐75%.

CCPT versus ACBT / FET

There were no eligible studies comparing ACBT with CCPT. One study conducted over more than two years (63 participants) compared CCPT with FET (Reisman 1988). The resulting publication reported that the annual decline in FEF25‐75% was significantly worse in the FET group than the CCPT group. There was also a tendency for the annual decline in FEV1 to be worse in the FET group which did not reach significance; differences in FVC were also non‐significant. RevMan analysis of these data produced similar results in terms of FEV1, MD 2.80 (95% CI ‐0.39 to 5.99); FVC, MD 1.80 (95% CI ‐0.83 to 4.43); and FEF25‐75%, MD 6.00 (95% CI: 0.55 to 11.45) (Reisman 1988).

CCPT versus AOD

Two randomised controlled trials comparing CCPT with airway oscillation devices (38 participants) were conducted over six months and two weeks respectively (Homnick 1995; Homnick 1998). There was no overall mean difference between CCPT and airway oscillation devices in terms of FEV1, MD 0.80 (95% CI ‐5.79 to 7.39); FVC, MD 6.06 (95% CI ‐2.42 to 14.55); or FEF25‐75%, MD 1.26 (95% CI ‐7.56 to 10.09). One of these studies showed a tendency to favour CCPT over flutter in terms of improvements in FVC (Homnick 1998).

CCPT versus AD

Two studies comparing CCPT with autogenic drainage (36 participants) were included in meta‐analysis (Davidson 1992; McIlwaine 1991) They were conducted over one year and two months respectively. No significant differences between CCPT or AD were demonstrated in terms of FEV1, MD 1.81 (95% CI ‐2.52 to 6.14); FVC, MD 0.39 (95% CI ‐3.62 to 4.40); or FEF25‐75%, MD ‐0.42 (95% CI ‐5.38 to 4.54). Both publications reported no difference in these outcomes between techniques (Davidson 1992; McIlwaine 1991). Effect of time, if any, could not be assessed.

CCPT versus exercise

One randomised controlled trial, with 17 participants, conducted over two weeks compared CCPT (three sessions a day) with exercise and CCPT (two exercise and one CCPT sessions per day) (Cerny 1989). The resulting publication reported that while both groups improved significantly during the hospital admission, differences between groups were non‐significant. However, RevMan analysis of data provided by the author showed significantly more improvement in respiratory function in the CCPT group than the exercise group: FEV1, MD 7.05 (95% CI: 3.15 to 10.95); FVC, MD 7.83 (95% CI: 2.48 to 13.18); and FEF25‐75%, MD 4.74 (95% CI: 1.94 to 7.54) (Cerny 1989). These results should be interpreted with caution. There were important differences in baseline respiratory function values between groups in this study, with those in the CCPT having significantly lower FEV1, FVC and FEF25‐75% values. This would almost certainly have influenced the magnitude of improvement during a two‐week admission for acute exacerbation.

Effects of study duration

Data from included studies showed wide heterogeneity, apparently unrelated to any systematic or predictable effects of treatment duration. If, during future updates of this review, new data indicate an effect of treatment duration, it will be appropriate to reassess data in this respect and production of comparative tables may be helpful.

Predictably, all four studies undertaken during two‐week acute exacerbations demonstrated relatively large gains in FEV1 (range: 8.2% to 18.4% predicted); FVC (range of change: 8.3% to 22.5% predicted); and FEF25‐75% (range: 4.04% to 11.20% predicted), irrespective of treatment technique (Arens 1994; Bauer 1994; Cerny 1989; Homnick 1998). These results reflect a combination of low baseline pulmonary function prior to admission and then marked improvement as a result of intense therapy including antibiotics, nutritional supplements, inhalation therapy and physiotherapy.

In contrast to studies undertaken during pulmonary exacerbations, studies conducted between one and six months demonstrated noticeably smaller improvements or deterioration over time for FEV1 (range ‐3.38% to 4.44% predicted); FVC (range: ‐4.44% to 10.20% predicted); and FEF25‐75% (‐2.45% to 3.37% predicted). Studies conducted over one year or more also demonstrated similar smaller changes in FEV1 (range: ‐4.70% to 5.98% predicted); FVC (range: ‐2.54% to 6.57% predicted); and FEF25‐75% (range ‐10.20% to 6.95% predicted).

Secondary outcomes

2. Adherence to therapy and individual preference

These data were not incorporated into comparative tables, because of substantial heterogeneity in methods used to obtain the results. Of the 15 studies included, five did not make reference to therapy adherence or individual preference (Cerny 1989; Homnick 1998; Kraig 1995; Reisman 1988; Van Asperen 1987).

CCPT versus PEP

Four of six studies comparing PEP with CCPT reported from questionnaires administered that individuals preferred PEP (Costantini 1998; Darbee 1990; McIlwaine 1997; McIlwaine 1991). Reasons for preference included comfort, convenience, independence, ease of use, more control and flexibility over treatment times and less interruption to daily living. Costantini reported that both infants and their parents "greatly" preferred PEP to CCPT (Costantini 1998). Another study did not formally assess individual preference, but noted that comments about PEP were generally favourable and that six months after completion of the study, 9 out of 16 individuals used PEP exclusively, four used it in addition to CCPT and three had no benefit from PEP (Tyrrell 1986).

McIlwaine reported that 92% of the CCPT group adhered to treatment compared to 96% of the PEP group, but did not report whether these results were significant (McIlwaine 1997). Other studies made reference to participants keeping compliance diaries, but data were not reported in the abstract (Gaskin 1998). No other studies commented on adherence.

CCPT versus HFCC / MP

Via a telephone survey, Bauer found that of the study participants who responded: 48% preferred mechanical percussion; 26% preferred manual percussion; and 26% expressed no preference (Bauer 1994). Arens reported that 22 participants (88%) expressed satisfaction with HFCC and requested it for future management of acute pulmonary exacerbations (Arens 1994). They did not assess satisfaction within the CCPT group (Arens 1994).

CCPT versus ACBT / FET

The included study did not report on this outcome (Reisman 1988).

CCPT versus AOD

Homnick reported individual acceptance and satisfaction with using IPV, but did not assess satisfaction within the CCPT group (Homnick 1995). All eight individuals in the IPV group expressed a wish to continue with this therapy.

CCPT versus AD

Both studies comparing AD with CCPT reported a preference for AD (Davidson 1992; McIlwaine 1991). Davidson suggested that participants exhibited a "marked preference" for the AD technique, and at the end of the first arm of this study, 8 out of 18 participants using AD apparently refused to revert to CCPT and a further 5 out of 18 were discovered to be using AD after they had supposedly reverted back to CCPT.

CCPT versus exercise

The included study did not report on this outcome (Cerny 1989).

3. Quality of life measures

Only one study assessed quality of life using the 'Quality of Well Being Scale' (QWB) (Gaskin 1998). No change in either the PEP or CCPT groups was reported over the duration of the study. There is likely to be a degree of overlap between perceived quality of life and individual preference with therapy reported above, especially when expressed in terms of convenience, independence, ease of use, control and flexibility over treatment times and interruption to daily living.

4. Number of respiratory exacerbations per year

None of the included studies reported on this outcome.

5a. Number of days in hospital per year

CCPT versus ACBT / FET

One study (63 participants), reported no statistical difference in average number of days per participant in hospital, when comparing CCPT with FET. Data from this study were not suitably formulated for meta‐analysis (Reisman 1988).

CCPT versus AOD

One study (16 participants) reported no difference in the average number of days per participant in hospital, when comparing CCPT with IPV, RR 1.70 (95% CI ‐3.55 to 6.95) (Homnick 1995).

5b. Number of admissions per year

CCPT versus PEP

One study (36 participants), reported no difference in number of hospitalisations per group, when comparing CCPT with PEP, RR 0.85 (95% CI 0.51 to 1.41) (McIlwaine 1997)

CCPT versus ACBT / FET

One study (63 participants), reported no difference in number of hospitalisations, when comparing CCPT with FET, RR 0.61 (95% CI 0.23 to 1.62) (Reisman 1988).

6. Number of days of intravenous antibiotics per year

Costantini found that days on antibiotic therapy were higher for infants using PEP (29.6 versus 18.2 days) over 12 months, but did not comment on the significance of these values, or specify whether these were IV or oral courses (Costantini 1998). Homnick found no difference in the number of oral or IV antibiotics administered to the CCPT or IPV groups over the six‐month study period (Homnick 1995).

7. Objective change in exercise tolerance

Three studies used exercise testing as an outcome in their studies. One tested exercise using cycle ergometry (Gaskin 1998); a second used a graded exercise challenge test (Reisman 1988); and the third used an unspecified exercise test (Cerny 1989). Data were not reported in the Gaskin study (Gaskin 1998), but both other studies found no significant differences between treatment groups (Cerny 1989; Reisman 1988).

8. Total lung capacity and functional residual capacity

Few studies reported pulmonary function parameters other than FEV1, FVC and FEF25‐75%. However, two studies reported TLC and RV (Arens 1994; Homnick 1998), while others reported either RV (Cerny 1989) or TLC (Darbee 1990). None of these studies found significant differences between treatment groups for any of these secondary outcome measures.

9. Mucus transport rate as assessed by radioactive tracer clearance

One study used radioactive tracer clearance to compare efficacy of CCPT versus PEP, but found no differences in TC‐99m‐diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (TC‐99m‐DTPA) clearance in either group (Darbee 1990).

10. Radiological ventilation scanning

No studies reported radiological ventilation scanning as an outcome. However, four studies reported chest radiographic scores, but used different or non‐standardised scoring systems, or did not report data (Costantini 1998; Gaskin 1998; McIlwaine 1997; Tyrrell 1986). It may be useful to reflect this score preference in future updates of this review, but any meaningful comparisons would require consistent use of standardised outcomes.

11. Oxygen saturation measured by pulse or transcutaneous oximetry

Two studies included used oxygen saturation as an outcome and demonstrated no difference between treatment groups (Arens 1994; Costantini 1998).

12. Cost / benefit analysis of intervention

No studies formally assessed this outcome.

13. Nutritional status as assessed by growth, weight and body composition

Homnick found no difference in body mass index between the CCPT and IPV groups (Homnick 1995). Arens reported weight gain in both groups during hospitalisation for acute exacerbation, but reported no differences between the CCPT and HFCC groups (Arens 1994).

14. Mortality

None of the included studies reported on this outcome.

Additional outcomes which have arisen from the review

15. Adverse events

Although they were not identified for inclusion in the protocol, adverse events were sporadically reported and may warrant inclusion in future updates of this review. All were reported as tenuously linked to therapy and may have been spontaneous or unrelated. Costantini reported that adverse events were rare, with only one individual on PEP suffering from gastro‐oesophageal reflux and another experiencing a transient episode of atelectasis (complete or partial collapse of the lung) (Costantini 1998). McIlwaine reported no adverse events in either CCPT or PEP groups (McIlwaine 1997). Homnick reported that one participant on IPV had minor haemoptysis (coughing up blood), but was not withdrawn from the study and was treated for pulmonary exacerbation (Homnick 1995). Arens found that one individual in the HFCC and two individuals in the CCPT groups had mild haemoptysis. In all cases treatment was discontinued for 24 hours, and then resumed (Arens 1994). Some participants in the HFCC group reported mild chest pain and nausea during first two to three days which subsequently resolved (Arens 1994).

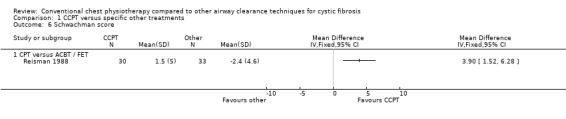

16. Other outcomes

Other outcomes were inconsistently reported and included Schwachman clinical scores (McIlwaine 1997; Reisman 1988). McIlwaine found no difference between groups (McIlwaine 1997), while Reisman reported they were worse after FET, MD 3.90 (95% CI 1.52 to 6.28) (Reisman 1988). Both these studies also reported sputum bacteriology, but found no difference between treatment groups.

A few studies involved participants keeping daily diary cards to record, most commonly, a cough score (Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987) and sputum production (Arens 1994; Kraig 1995; Tyrrell 1986; Van Asperen 1987). No differences between treatment groups were found.

Discussion

This review set out to determine if there was any advantage of CCPT (a technique used for more than five decades to clear pulmonary secretions) over other ACTs (more recently developed to encourage independence in self‐care). Outcomes included pulmonary function, individual preference, adherence to therapy, quality of life measures and number of hospitalisations per year. Studies of less than seven days duration, including single treatment studies, were excluded. CF is a chronic disorder in which single treatment or short‐term studies are inadequate in describing efficacy, safety or long‐term acceptability of any interventions for this cohort.

The review of data from 15 trials comparing these groups could not demonstrate that any of the newer techniques were better than CCPT in people with CF, but this may have reflected insufficient data for meta‐analysis rather than equivalence between techniques. There was limited evidence that participants preferred other techniques rather than CCPT. Evidence on adherence was inadequate to make any conclusions on choice of technique.

A feature of the meta‐analysis of FEV1, FVC and FEF25‐75% data was the substantial heterogeneity in results between studies. These results may reflect differences between centres in terms of treatments, training or measurement techniques. However, even within individual centres, studies undertaken less than a decade apart, comparing the same interventions, demonstrated results that were not in agreement (McIlwaine 1991; McIlwaine 1997). Another factor that may have contributed to the heterogeneity of these results could be the small numbers per participant group seen across virtually all studies. No single study recruited more than 36 participants to each study group and the mean number was far lower than this, introducing the possibility that most studies included in this review were inadequately powered to find differences between treatments if they existed and estimates of effect would be imprecise.

The absence of difference between treatments as demonstrated by the primary outcome measures chosen for this review may indicate that there are indeed no differences between treatment techniques. However, it may also indicate that the outcome measures selected for this review and for the original studies, were too insensitive to detect differences between treatments. It is possible that future studies may need to identify more sensitive indices of lung function such as lung clearance index or pulmonary scanning. However, measures such as these have not yet been validated in terms of clinical importance or relevance.

There were generally no systematic differences between CCPT and other ACTs in terms of the secondary outcome measures. The single exception to this was 'individual preference'. Ten studies included a measure of individual preference that showed, without exception, that individuals preferred to use ACTs that were self‐administered and thus facilitated independence. For example, five out of six studies comparing CCPT with PEP demonstrated a preference for PEP (the remaining study did not measure individual preference). In addition, both studies comparing CCPT with AD demonstrated a preference for AD. Reasons for preference included comfort, convenience, independence, ease of use, more control and flexibility over treatment times and less interruption to daily living. Three of four studies comparing CCPT with mechanical percussive devices indicated that participants were satisfied with the devices, but only one of these assessed individual satisfaction within the CCPT group and found that the majority preferred mechanical percussion.

It is difficult to assess the extent to which researchers viewpoints may have influenced individual reporting of preference or satisfaction, especially since current trends tend to favour independence and self‐therapy in terms of ACTs. No studies used standardised or comparable measures of individual preference but some studies measured this in a rather informal fashion. In the absence of any other clear objective distinctions between treatments, softer parameters such as individual preference seem to escalate in importance. This is particularly pertinent in a lifelong disease such as CF, where it is assumed that compliance with ACTs will be associated with a smaller annual decline in respiratory function. It is also assumed that the more satisfied individuals are with a treatment regimen, the more likely they will be to adhere to treatment.

An important issue that arose from examination of raw data submitted by authors was that, although group differences may not have indicated significant changes between treatments, it was clear that some participants responded extremely positively or negatively to individual treatments. In terms of individual patient management, 'statistical' recommendations may not always be appropriate and some experimentation may be required to provide the perfect solution for a particular individual's needs. As further studies are conducted, it may become apparent that some techniques may better suit certain ages and stages of the disease. Other factors such as pulmonary hyperreactivity may, for example, preclude certain techniques. There was no evidence from meta‐analysis of available studies that any technique offered an advantage during acute pulmonary exacerbation compared to stable disease.

There was a great sense of frustration when original data could not be found by authors and could not be retrieved from the published manuscript. At times, a degree of re‐analysis of original data was required, and this presented the possibility that the outcome described in the original paper would not quite be duplicated following re‐analysis for the purpose of meta‐analysis (this did not occur in the data submitted to date). In general, the systematic review of physiotherapy studies for CF present substantial challenges because of the great number of interventions, outcome measures and study durations. There has been a great deal of professional debate with regard to terminology reflecting the specific interventions. It is thus likely to cause some discomfort that we have chosen to lump, for the purpose of meta‐analysis, certain interventions that appear to have similarities, for example those involving mechanical percussive devices. In future updates of this review and in the presence of large numbers of studies related to each intervention, there would be no need for such combinations.

Systematic reviews of physiotherapy studies also face the challenge of problematic quality selection systems used for scoring individual studies. Validated scoring systems such as those proposed by Jadad place great value upon randomisation and double blinding (Jadad 1996). While randomisation and complete follow up remain important criteria in physiotherapy studies, many physiotherapy studies cannot easily incorporate blinding and are inevitably disadvantaged when measured using such scores. These studies become vulnerable to exclusion from review and the potential to recognise valuable clinical information may be missed. In this review, no studies were excluded on the basis of low quality scores.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There appeared to be no advantage of CCPT over other ACTs in terms of effect on respiratory function. It is important to note that this result may simply reflect the paucity of evidence rather than a definitive conclusion that CCPT is no better than any of the alternatives. The studies included generally scored poorly on quality assessment and it is likely that no single study was adequately powered to identify clinical differences. More long‐term, well‐designed studies with adequate participant numbers are needed to resolve this issue. There appeared to be a tendency for individuals to prefer self‐administered ACTs. These seemed to offer more choice, independence and convenience in performing this daily routine. Clinicians may consider this when providing advice on which ACT is most appropriate for individuals old enough to be capable of self‐treatment.

It was clear from examination of original data that individual responses to therapies were extremely variable. Some individuals improved significantly while others deteriorated. In light of the fact that this review cannot yet recommend any single treatment above others, physiotherapists and people with CF might feel more comfortable about trying various ACTs until a method is found that suits the individual best.

Implications for research.

More than half the publications relevant to this review were excluded on the basis of study design; almost without exception because they involved single treatments or study duration of less than seven days. These study designs were purported to provide some information on treatment safety and efficacy. The chronic nature of CF necessitates daily treatment during the individual's lifetime. It is thus unlikely that safety or efficacy can be demonstrated over very short study intervals. Only four studies out of the 15 identified for possible inclusion were undertaken over a period of one year or more. More adequately‐powered long‐term randomised controlled trials (parallel or cross‐over in design) need to be included in this review before clinically valuable information can be gained with regard to treatment efficacy and safety.

Trials of sufficient numbers and sufficient duration are recommended to determine if there is a difference in important outcome measures such as rate of decline in respiratory function, quality of life and independence. Other outstanding areas of research include identifying sensitive selection criteria (including age and severity of disease) for different treatment modalities. In addition, well‐established standard measures of respiratory function, for example FEV1, are proving to be insensitive in early disease. Development of more sensitive outcomes, for example inert gas washout techniques may improve the ability to differentiate between treatments, especially during childhood.

The wide between‐subject variability in response to physiotherapy treatments, continues to challenge healthcare professionals, but suggests that treatment selection may depend on factors that have not yet been identified. Future studies need to focus on the relationship between specific clinical or physiological features that may predict positive responses to specific treatment modalities. It may also be useful for studies to systematically monitor and record possible treatment‐related adverse effects.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 January 2013 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 1, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 February 2009 | Amended | Converted to new review format. The Synopsis has been replaced by a new Plain Language Summary. Amendments in light of comments from the Group's Statistician have been made throughout the review. |

| 18 February 2009 | New search has been performed | Following on from as search of the Group's Cystic Fibrosis Trials Register four trials have been added to excluded studies (Chatham 2004; Grasso 2000; Stites 2006; Warwick 2004). An additional reference to an already excluded trial was also added (Braggion 1995). |

| 15 November 2004 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Enormous gratitude is extended to authors who gave up valuable time to locate and send original data in order to facilitate this review. Data were gratefully received from Arens 1994, Bauer 1994, Cerny 1989, Costantini 1998, Darbee 1990, Davidson 1992, Gaskin 1998 (and from Dr Tullis), Homnick 1995, Homnick 1998, McIlwaine 1991, McIlwaine 1997, Orlik 2001, Tyrrell 1986 and Van Asperen 1987.

We are also extremely grateful for the support of Tracey Remmington (Review Group Co‐ordinator) and Ashley Jones (Medical Statistician).

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. CCPT versus specific other treatments.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 FEV1 (% predicted) | 14 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 CCPT versus PEP | 6 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐1.45, 1.62] | |

| 1.2 CCPT versus HFCC / MP | 3 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.76 [‐4.67, 1.16] | |

| 1.3 CCPT versus ACBT / FET | 1 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.80 [‐0.39, 5.99] | |

| 1.4 CCPT versus AOD | 2 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [‐5.79, 7.39] | |

| 1.5 CCPT versus autogenic drainage | 2 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.81 [‐2.52, 6.14] | |

| 1.6 CCPT versus exercise | 1 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.05 [3.15, 10.95] | |

| 2 FVC (% predicted) | 14 | mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 CCPT versus PEP | 6 | mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [‐1.56, 2.33] | |

| 2.2 CCPT versus HFCC / MP | 3 | mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.42 [‐5.17, 2.33] | |

| 2.3 CCPT versus ACBT / FET | 1 | mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.8 [‐0.83, 4.43] | |

| 2.4 CCPT versus AOD | 2 | mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.06 [‐2.42, 14.55] | |

| 2.5 CCPT versus autogenic drainage | 2 | mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.39 [‐3.62, 4.40] | |

| 2.6 CCPT versus exercise | 1 | mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.83 [2.48, 13.18] | |

| 3 FEF25‐75 (% predicted) | 11 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 CCPT versus PEP | 4 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.44 [‐3.38, 2.50] | |

| 3.2 CCPT versus HFCC / MP | 2 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [‐2.53, 3.52] | |

| 3.3 CCPT versus ACBT / FET | 1 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 6.0 [0.55, 11.45] | |

| 3.4 CCPT versus AOD | 2 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [‐7.56, 10.09] | |

| 3.5 CCPT versus autogenic drainage | 2 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.42 [‐5.38, 4.54] | |

| 3.6 CCPT versus exercise | 1 | Mean difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.74 [1.94, 7.54] | |

| 4 Number of hospital admissions | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 CPT versus PEP | 1 | 36 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.53, 1.35] |

| 4.2 CPT versus ACBT / FET | 1 | 63 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.23, 1.62] |

| 5 Number of days in hospital | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 CCPT versus AOD | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Schwachman score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 CPT versus ACBT / FET | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CCPT versus specific other treatments, Outcome 1 FEV1 (% predicted).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CCPT versus specific other treatments, Outcome 2 FVC (% predicted).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CCPT versus specific other treatments, Outcome 3 FEF25‐75 (% predicted).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CCPT versus specific other treatments, Outcome 4 Number of hospital admissions.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CCPT versus specific other treatments, Outcome 5 Number of days in hospital.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 CCPT versus specific other treatments, Outcome 6 Schwachman score.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Arens 1994.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Parallel design. | |

| Participants | 70 adult participants. Mean (SD) age: CCPT: 18 years (1.3); HFCC: 22.9 years (2.0). All participants completed. | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus HFCC. | |

| Outcomes | Sputum weight (wet and dry), VC, FEV1, FEF25‐75, SpO2, RV, RV/TLC. | |

| Notes | Jadad score: 2/5. 2‐week study duration, during acute pulmonary exacerbation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Bauer 1994.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Parallel design. | |

| Participants | 51 participants in publication (70 from author) randomly assigned to each group. Mean (SD) age: CCPT: 17 years (1.4); mechanical: 15.9 years (1.4). All participants completed. | |

| Interventions | CCPT using manual versus mechanical percussion. | |

| Outcomes | FVC, FEV1, FEF25‐75. | |

| Notes | Jadad score 2/5. Approximately 2‐week study, during acute pulmonary exacerbation. 22 participants on re‐admission were assigned to opposite group from their first admission. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Cerny 1989.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Parallel design. | |

| Participants | 17 participants. Mean (SD) age: CCPT: 15.9 years (4.9); exercise: 15.4 years (4.9). All participants completed. | |

| Interventions | CCPT (n=8) or exercise plus CCPT (n = 9). | |

| Outcomes | FVC, FEV1, FEF25‐75, ERV, IC, FRC, airway resistance, RV, TLC, exercise test, SAC. | |

| Notes | Jadad score 2/5. 2‐week study, during acute pulmonary exacerbation. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Costantini 1998.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Parallel design. | |

| Participants | 12 participants published. (Data on 27 participants obtained from author.) Age: within 2nd month of life at recruitment. | |

| Interventions | CCPT (n = 5) versus PEP (n = 7). | |

| Outcomes | SaO2, growth, CXR, antibiotic therapy, GOR. | |

| Notes | Jadad 2/5 (on abstract). 1‐year study in infants, 12th NACF conference abstract. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Darbee 1990.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Cross‐over design. | |

| Participants | 13 participants published (data on 20 participants obtained from author). Ages: 18‐34 years, mean (SD): 25.7 (5). | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus PEP. | |

| Outcomes | Radionucleotide clearance. FVC, FEV1, FEF, TLC. | |

| Notes | Jadad (cannot score: abstract). 4th NACF conference abstract. This study involved single assessments of radionucleotide clearance and respiratory function before and after 3 months after CPT and PEP. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Davidson 1992.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Cross‐over design. | |

| Participants | 36 participants. Ages: 12‐18 years. All participants completed first arm. | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus AD. | |

| Outcomes | FVC, FEV1, FEF25‐75 (Schwachman, hospital days ‐ but exploratory data only and not sent on request). | |

| Notes | Jadad score: (abstract only: cannot score). This cross‐over study was supposed to incorporate two arms (one year each arm). However AD arm in first year refused to return to CCPT. Thus only first arm used (1 year). This is the 6th NACF conference abstract. This is the same data reported in McIlwaine 11th International CF conference (1992). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Gaskin 1998.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Parallel design. | |

| Participants | 66 participants, of which 61participants completed. Ages: 11‐45 years. Mean (SD) age: CCPT 21.9 (8.7); PEP: 21.3 (8.0). | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus PEP. | |

| Outcomes | FVC, FEV1, QOL, exercise test, CXR score. | |

| Notes | Jadad score (2/5 based on abstract). This is the 12th NACF conference abstract (1998). This is the same data supplied by Tullis. 2‐year study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Homnick 1995.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Parallel design. | |

| Participants | 20 participants, of which 16 completed. Ages: 5‐24 years. CCPT: Mean (range) 10 years (5‐18 years); IPV: 12 years (5‐24 years). | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus IPV. | |

| Outcomes | FVC, FEV1, FEF25‐75, BMI, patient log/preference, hospital admissions, intravenous antibiotic courses | |

| Notes | Jadad 3/5. 6‐month parallel comparative study: stratified randomisation. Article gives descriptions of adverse events. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate |

Homnick 1998.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Parallel design. | |

| Participants | 22 participants on 33 admissions. Ages: 8‐44 years, CCPT: Mean (range) 12 years (7‐21 years); flutter: 16.1 years (8‐44 years). | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus flutter. | |

| Outcomes | Sputum volume, FVC, FEV1, FEF25‐75, FEV/TLC, TLC, RV, RV/TLC, clinical score. | |

| Notes | Jadad score 2/5. Roughly 2‐week study, acute exacerbations. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Kraig 1995.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Cross‐over design. | |

| Participants | 5 participants. Ages not recorded. | |

| Interventions | Manual chest percussion versus acoustic percussion. | |

| Outcomes | Sputum, FVC and FEV1. | |

| Notes | Abstract only (cannot score). Data reviewed after 2 months. ATS 1995. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

McIlwaine 1991.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Cross‐over design. | |

| Participants | 18 participants. All completed. Ages not recorded. | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus PEP versus AD. | |

| Outcomes | Sputum, FVC, FEV1, FEF25‐75, FEV1/FVC. | |

| Notes | Jadad (cannot score on abstracts). Each of 3 arms 2 months long: with one month PD wash out period. This is the 17th European CF conference (McIlwaine 1991). It is the same data reported in 2nd NACF conference abstract (Davidson 1988) and the 10th International CF conference (McIlwaine 1988). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

McIlwaine 1997.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Parallel design. | |

| Participants | 40 participants, of which 36 completed. Ages: 6‐17 years. CCPT: Mean (range) 9.8 years (6‐14 years); PEP: 10.4 years (6‐17 years). | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus PEP. | |

| Outcomes | FVC, FEV1 and FEF25‐75, radiographic score (not reported). | |

| Notes | Jadad score 3/5. 1‐year long‐term study, participants with equivalent FEV1, age and sex were stratified. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate |

Reisman 1988.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Parallel design. | |

| Participants | 67 participants, of which 63 completed. Ages 7‐21 years, mild to moderate disease. | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus FET. | |

| Outcomes | FVC, FEV1 and FEF25‐75, hospital days, Schwachman, exercise test. | |

| Notes | Jadad score 3/5. Participants were stratified for age, sex and pulmonary impairment, then randomised. Trial over 2.4 years, data given as decline per year. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Adequate |

Tyrrell 1986.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Cross‐over design. | |

| Participants | 19 participants, all completed. Ages: 13 years (10‐18 years). Mean (SD) age: CCPT: 12.6 years (4.2); FET: 11.8 years (3). 3 excluded from analysis due to non‐compliance, mild to moderate disease. | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus PEP. | |

| Outcomes | PEFR, FEV 0.75, FVC, sputum volume, Schwachman but not reported. | |

| Notes | Jadad score 2/5, 4 weeks each arm. Received raw data from authors. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

Van Asperen 1987.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial. Cross‐over design. | |

| Participants | 13 participants, of which 10 completed. Ages: 7‐18 years. | |

| Interventions | CCPT versus PEP. | |

| Outcomes | Sputum volume, FEV1, FEF25‐75, cough score, activity score, PEFR. | |

| Notes | Jadad score 2/5, 4 weeks each arm. Published data in L/s, but % predicted obtained from authors. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear |

AD: autogenic drainage ATS: American Thoracic Society BMI: body mass index CCPT: conventional chest physiotherapy CXR: chest X‐ray ERV: expiratory reserve volume FET: forced expiratory technique FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second FEF25‐75: forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% expired FVC FRC: functional residual capacity FVC: forced vital capacity GOR: gastro‐oesophageal reflux HFCC: high frequency chest compression IC: inspiratory capacity IPV: intrapulmonary percussive ventilation L/s: litres per second NACF: North American Cystic Fibrosis PD: postural drainage PEF: peak expiratory flow PEFR: peak expiratory flow rate PEP: positive expiratory pressure QOL: quality of life RV: residual volume SaO2: saturation of haemoglobin with oxygen in arterial blood SpO2: saturation of haemoglobin with oxygen using pulse oximetry TLC: total lung capacity

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Baldwin 1994 | Study less than 7 days in duration. Cross‐over: 1 treatment each of 2 regimens over 2 non‐consecutive days. Outcomes FEV1, FVC, FEF25, peak flow and sputum weight. CCPT versus CCPT plus exercise, 8 participants. |

| Braggion 1995 | Less than 7‐day study: Excluded because 2 treatments for 2 days for each of 4 interventions, 16 participants, Sputum, wet and dry, tolerance. CCPT versus PEP versus HFCC versus control. |

| Button 2003 | CCPT with and without head down tip. Over 12 months, outcomes involved cough days, annual upper respiratory tract infections, wheeze days, etc. Excluded because the study focus is on 'effect of tip' more than effect of CCPT. |

| Chatham 2004 | Less than 7‐day study: Single treatment cross‐over. Twenty adults with cystic fibrosis. Outcome measures included sputum weight, inflammatory markers and protein content. 'Standard' physiotherapy includes ACBT and therefore not strictly 'conventional' as defined in this protocol. |

| de Boeck 1984 | Less than 7‐day study: One treatment on 2 consecutive mornings. Vigorous coughing versus CCPT. Outcomes Pulmonary function and volume of sputum, 9 participants. |

| Desmond 1983 | CCPT versus no physiotherapy. Cross‐over study, 8 children. |

| Falk 1984 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over, 1 treatment session each for 4 regimens over 2 days, SaO2, sputum weight, FEV, PEF, 14 participants. |

| Giles 1995 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over. Two treatment regimens over 2 days. CCPT versus autogenic drainage. Pulse oximetry, sputum and PEF, FEV1 and FVC. 10 participants, 1 treatment each, 3 minutes of 7 positions. |

| Grasso 2000 | Twelve week study. Twenty children were randomised to two groups with different music therapy used as adjunct to conventional treatment. Outcomes were 'enjoyment' and 'perception of time' |

| Hartsell 1978 | CCPT versus mechanical percussor, single treatment only, PFTs. Includes non‐CF patients. Abstract only, 6 participants. |

| Kerrebijn 1982 | Less than 7‐day study: Single treatments comparing CCPT with aerosol treatment. |

| Kluft 1996 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: 29 patients (7 to 47 yrs), 2 days each of CCPT and high frequency chest wall oscillation over a 4‐day period. Wet and dry sputum measured. |

| Konstan 1994 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: Three regimens each performed twice over 2 weeks. 18 patients (8 to 38 years). CCPT versus flutter versus cough. Wet and dry sputum. |

| Lannefors 1992 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: One treatment of each of three regimens over 3 separate days. Tc clearance. 9 participants included. |

| Maayan 1989 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: 1 treatment each of 4 regimens, conventional chest physiotherapy versus two aerosols versus CCPT plus aerosol. 19 infants under one year randomised into 4 groups. Infant plethysmograph and vmax FRC. |

| Majaesic 1996 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: 7 participants (6 to 18), CCPT versus HFCC, outcome viscosity and spinnability. |

| Marks 2000 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: Single treatment: Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation versus CCPT, 10 patients, PFT, sputum wet and dry. |

| Maxwell 1979 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: Single treatment of mechanical versus manual percussion. Sputum volume and FEV1, FVC. n=14 |

| Morris 1982 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: CCPT versus mechanical percussor, one treatment each regimen, 18 participants. |

| Natale 1994 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: 3 regimens over 5 days, one treatment each, CCPT versus Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation, LFT and sputum volume. 9 participants. |

| Newhouse 1998 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: single interventions of 3 regimens cross‐over, CCPT versus Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation versus flutter, 8/10 patients, PFT, SaO2, sputum wet weight. |

| Oberwaldner 1986 | Excluded because of ABC 'withdrawal' study design: 20 patients, (A = 10 months of High Pressure PEP, then B=2 months reverting to pre‐study treatment (10 with FET and 10 with CCPT), then C=6 months PEP). Outcomes were PFT, and mucous clearance. |

| Orlik 2001 | Excluded because study groups not randomised. 4 groups over 7 months. 80 patients (6‐18) PD with clapping (33) versus PD with clapping and vibrations (16) vs ACBT (18) versus Flutter (13). Outcomes were FVC, FEV1 and FEF25‐75, MEF. |

| Pryor 1979 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: CCPT versus FET. 2 treatments only. |

| Rossman 1982 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: One treatment each of 5 regimens over 5 days, 6 participant, Outcome: Tc clearance. |

| Samuelson 1994 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over single treatment study. CCPT versus therabed. |

| Scherer 1998 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: Excluded: 1 treatment each of 5 regimens. 2 forms of HF oral airway and 2 forms of chest wall oscillation versus CCPT. 14 participants (12 to 34) with stable CF. |

| Stites 2006 | Less than 7‐day study: Single treatment cross‐over. Ten adults. Primary outcome was deposition of DPTA following CCPT or during HFCWO. Cross‐over interval variable between 72 hours and 10 days. |

| Tonnesen 1984 | Cross‐over non‐randomised study, second arm prospective (first arm retrospective). 15 participants (12 to 29 years), mild to severe disease, 3 excluded. CCPT versus PEP. PEF, FEV1, FVC. 6 to 9 months CCPT versus 6 to 9 months PEP. Author contacted ‐ data have been lost. Data could not be extracted from paper. |

| Warwick 1990 | Less than 7‐day study: Randomised cross‐over: Abstract of 4th NACFC, 1 treatment each of 4 regimens. |

| Warwick 2004 | Less than 7‐day study: While this was conducted over 2 weeks, the study design comprised a series of four single treatment session over four days. Interventions were conventional physiotherapy and HFCC. Twelve men participated. Outcome measures were wet and dry sputum weight. |

ACBT: active cycle of breathing therapy CCPT: conventional chest physiotherapy HFCC: high frequency chest compression NACFC: North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference PEP: positive expiratory pressure

Contributions of authors

Eleanor Main, Ammani Prasad and the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group conducted searches for relevant studies.

Eleanor Main, Ammani Prasad and Cees van der Schans wrote the protocol for the review and independently evaluated which studies should be included.

Eleanor Main and Ammani Prasad extracted data from included studies, liaised with the authors of studies to obtain additional data, performed data entry, data analysis, interpretation of the results and wrote the review.

Eleanor Main acts as guarantor for this review.

Declarations of interest

None known

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Arens 1994 {published data only}

- Arens R, Gozal D, Omlin KJ, Vega J, Boyd KP, Keens TG, et al. Comparison of high frequency chest compression and conventional chest physiotherapy in hospitalized patients with cystic fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1994;150(4):1154‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arens R, Gozal D, Omlin KJ, Vega J, Boyd KP, Keens TG, et al. Comparitive efficacy of high frequency chest compression and conventional chest physiotherapy in hospitalized patients with cystic fibrosis [abstract]. Pediatric Pulmonology 1993;Suppl 9:239. [Google Scholar]

Bauer 1994 {published data only}

- Bauer M, Schoumacher R. Comparison of efficacy of manual and mechanical percussion in cystic fibrosis [abstract]. Pediatric Pulmonology 1990;Suppl 5:249. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer ML, McDougal J, Schoumacher RA. Comparison of manual and mechanical chest percussion in hospitalized patients with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatrics 1994;124(2):250‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cerny 1989 {published data only}

- Cerny FJ. Relative effects of bronchial drainage and exercise for in‐hospital care of patients with cystic fibrosis. Physical Therapy 1989;69(8):633‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Costantini 1998 {published data only}

- Costantini D, Brivio A, Brusa D, Delfino R, Fredella C, Russo M, et al. PEP mask versus postural drainage in CF infants a long‐term comparative trial [abstract]. Pediatric Pulmonology 2001;Suppl 22:308. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini D, Brivio A, Delfino R, Fredella C, Russo MC, Sguera A. PEP mask versus postural drainage in CF infants a long‐term comparative trial [abstract]. Proceedings of the 24th European Cystic Fibrosis Conference; 2001 June 6‐9; Vienna, Austria. 2001:P100.

- Costantini D, Brivio A, Delfino R, Sguera A, Brusa D, Padoan R, et al. PEP mask versus postural drainage in CF infants [abstract]. Pediatric Pulmonology 1998;Suppl 17:342. [Google Scholar]

Darbee 1990 {published data only}

- Dadparvar S, Darbee J, Jehan A, Bensel K, Slizofski WJ, Holsclaw D. Tc‐DIPA aerosol ventilation evaluates the effectiveness of PEP mask in the treatment of cystic fibrosis [abstract]. European Respiratory Journal 1995;8(Suppl 19):177s. [Google Scholar]

- Darbee J, Dadparvar S, Bensel K, Jehan A, Watkins M, Holsclaw D. Radionuclide assessment of the comparative effects of chest physical therapy and positive expiratory pressure mask in Cystic Fibrosis [abstract]. Pediatric Pulmonology 1990;Suppl 5:251. [Google Scholar]

Davidson 1992 {published data only}

- Davidson AGF, Wong LTK, Pirie GE, McIlwaine PM. Long‐term comparative trial of conventional percussion and drainage physiotherapy versus autogenic drainage in cystic fibrosis [abstract]. Pediatric Pulmonology 1992;14(S8):235. [Google Scholar]

- McIlwaine PM, Wong LTK, Pirie GE, Davidson AGF. Long‐term comparative trial of conventional percussion and drainage physiotherapy versus autogenic drainage in cystic fibrosis [abstract]. Proceedings of the 11th International Cystic Fibrosis Congress; 1992. 1992:AHP42.

Gaskin 1998 {published data only}

- Gaskin L, Corey M, Shin J, Reisman JJ, Thomas J, Tullis DE. Long term trial of conventional postural drainage and percussion vs. positive expiratory pressure [abstract]. Pediatric Pulmonology 1998;Suppl 17:345. [Google Scholar]

Homnick 1995 {published data only}