Abstract

Based on its pathological characteristics, breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease. Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive subtype, and due to a lack of effective therapeutic targets, patients with TNBC do not significantly benefit from endocrine or anti-HER2 therapy. Conventional chemotherapy has been regarded as the only systemic therapy option for TNBC, but its therapeutic efficacy remains limited. Estrogen receptor β (ERβ) has been identified as a tumor suppressor in TNBC. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to identify the role of ERβ in regulating the response to chemotherapy, and to investigate its underlying mechanism in TNBC. MDA-MB-231 and BT549 cells were treated with doxorubicin (DOX), liquiritigenin [Liq, (Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals, Ltd.); a specific ERβ agonist], or a combination of DOX and Liq in vitro. The effects of various treatments on cell viability and proliferation were measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 and colony-formation assays, respectively. MDA-MB-231 and ERβ knockdown (ERβ-KD) MDA-MB-231 cells were selected for the establishment of ERα-/ERβ+ and ERα-/ERβ- cell models, respectively. The two cell models were treated with DOX, Liq or a combination of DOX and Liq. The effects of the treatment on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway were evaluated by assessing the protein expression levels of AKT and mTOR using western blot analysis. Low Liq concentrations increased the sensitivity of MDA-MB-231 and BT549 cells to DOX. Moreover, the synergistic effect of Liq and DOX treatment was associated with the inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in MDA-MB-231 cells, and the effect was ERβ-dependent. The results suggested that elevated ERβ expression was associated with sensitivity to doxorubicin by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway; therefore, the combined use of conventional chemotherapeutic drugs with ERβ agonists may serve as an effective therapy for TNBC.

Keywords: estrogen receptor β, liquiritigenin, triple negative breast cancer, PI3K/AKT/mTOR

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant primary tumor in women worldwide, and the incidence is continually on the increase (1). Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), which accounts for 10-20% of newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer (1,2), is defined by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER)α, progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression. Based on the pathological features, TNBC is an aggressive subtype with a poor prognosis, due to a high rate of early recurrence and distant metastasis (3). The poor prognosis is due to the lack of efficacy of the current systemic therapies, including endocrine-based and HER2-targeted therapies (4). Conventional chemotherapy is the standard strategy for the systemic treatment of advanced TNBC; however, the therapeutic efficacy in TNBC is not satisfactory. It has been reported that 34% of patients with newly diagnosed TNBC will undergo recurrence within five years, following adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (5). Therefore, combination therapies that enhance the sensitivity and improve the tolerance of chemotherapy are required for the effective treatment of TNBC.

ERα is a major determinant in classifying the various subtypes of breast cancer, and is also an indicator of endocrine therapy. The role of ERα in breast cancer has been clearly demonstrated (6). By contrast, ERβ, another estrogen receptor subtype, is not well characterized. It has been reported that ERβ, which is expressed in 30% of TNBC cases (7), is a key regulator of signal transduction and tumor suppression in breast cancer (8). Furthermore, ERβ displays an antiproliferative role in TNBC (9). Patients with ERβ-positive TNBC displayed an improved 5-year survival rate compared with patients with ERβ-negative TNBC (10). However, research into the role of ERβ during TNBC has primarily focused on endocrine therapy, and little has been reported regarding the role and therapeutic value of ERβ in chemotherapy. A large-scale retrospective study reported that the upregulation of ERβ1 (the fully functional isoform of ERβ) predicted an improved prognosis for patients with TNBC. In the study, 508 out of 571 (89.0%) patients with TNBC were successfully treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (11). However, whether the status of ERβ in TNBC is associated with the response to chemotherapy requires further investigation. Therefore, it is important to identify the role of ERβ in regulating the response to chemotherapy and its underlying mechanisms in TNBC.

In the present study, the inhibitory effects of doxorubicin and a combination therapy [doxorubicin and liquiritigenin (Liq)] on ERβ-positive TNBC MDA-MB-231 and BT549 cell lines were investigated in vitro. The results suggested that upregulated ERβ expression in TNBC cells was associated with improved sensitivity to doxorubicin by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway.

Materials and methods

Cells and reagents

TNBC MDA-MB-231 and BT549 cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Liq, an ERβ agonist, was purchased from Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals, Ltd.

Cell viability assay

To analyze the effects of different treatments on the viability of MDA-MB-231 and BT549 cells, a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells (5x103 cells/well) were plated in 96-well plates at 37˚C for 24 h. Subsequently, various agents, Liq (0-160 µg/ml, Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals, Ltd.) alone, doxorubicin (DOX; 0-4 ng/ml, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) alone or a combination of DOX (0-4 ng/ml) and Liq (40 µg/ml) were added to each well, whilst the control cells were treated with DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Following a 48-h incubation at 37˚C, 10 µl CCK-8 reagent was added to each well and incubated for a further 2 h at 37˚C. The absorbance of each well was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a multi-mode microplate reader (ELx800; Bio-Tek China). The IC50 of DOX and Liq was calculated using SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS, Inc.). Assays were performed in triplicate.

Lentivirus production and cell infection

shRNA targeting ERβ or negative control (NC) scramble sequence were sub-cloned into the GV112 vector (Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd.), respectively. The shRNA sequences were designed by Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. (shERβ, 5'-GCTGAATGCCCACGTGCTT-3'; shNC; 5'-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3'). For the production of lentivirus, the expression vectors (20 µg) were co-transfected with packaging plasmid pHelper 1.0 vector (15 µg) and envelope plasmid pHelper 2.0 vector (10 µg; Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd.) into 293T cells using TransIT®-LT1 (Mirus Bio, LLC). The supernatant was collected 72 h after transfection, concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 60,000 x g for 90 min at 4˚C and resuspended with OptiMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). MDA-MB-231 cells (2x104 cells/well) were cultured in 12-well plates for 24 h at 37˚C before transduction. The shERβ or shNC lentivirus particles (multiplicity of infection, 10) were respectively added into the medium. After 24 h at 37˚C, the culture medium was removed and replaced with complete medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing puromycin. The cells were incubated for 7 days at 37˚C to obtain stable ERβ knockdown (ERβ-KD)-MDA-MB-231 cells (an ERα-/ERβ- cell model). Subsequently, the ERβ-KD-MDA-MB-231 cells were divided into three groups for subsequent experiments. Western blot analysis was used to assess the efficiency of transduction.

Colony formation assay

Colony formation assays were performed to evaluate the effect of the different treatments on cell proliferation. MDA-MB-231 and ERβ-KD-MDA-MB-231 cells were selected. Single cell suspensions were prepared using 0.25% trypsin at 37˚C for 30 sec. Subsequently, cells at a density of 1x103 cells/ml were cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS, 40 µg/ml Liq, 1 ng/ml DOX or 1 ng/ml DOX and 40 µg/ml Liq. Cells were incubated at 37˚C with 5% CO2 for 10-14 days until macroscopic clones appeared. The colonies were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min, and stained with 0.1% Giemsa (AppliChem GmbH) at room temperature for 30 min. Colonies containing >50 cells were counted using an inverted light microscope (magnification, x100). The assay was performed in triplicate.

Western blotting

Western blotting was used to evaluate the protein expression levels of ERβ, AKT and mTOR. MDA-MB-231 and ERβ-KD-MDA-MB-231 cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed using a protein gel buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, 10% SDS and 10% glycerol) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride for 20 min at 4˚C. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C and the supernatants were collected. Protein concentration was quantified using a Nanodrop nd-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein (20 µg) was resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated for 24 h at 4˚C with primary antibodies targeted against: Phosphorylated (p)-mTOR (cat. no. 2974; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), mTOR (cat. no. 2983; 1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), ERβ (cat. no. sc-8974; 1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), β-actin (cat. no. 4970; 1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), phosphorylated (p)-AKT (cat. no. 4060; 1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and total AKT (cat. no. 4691; 1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Following primary incubation, the membranes were washed three times with TBST and subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (cat. no. AS014; 1:5,000; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (EMD Millipore). Blots were performed in at least triplicate. The protein expression levels were quantitatively analyzed using the Image lab 6.0 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and normalized against β-actin loading control.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test was used to analyze the data. Comparisons between multiple groups and across multiple factors were made using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS, Inc.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

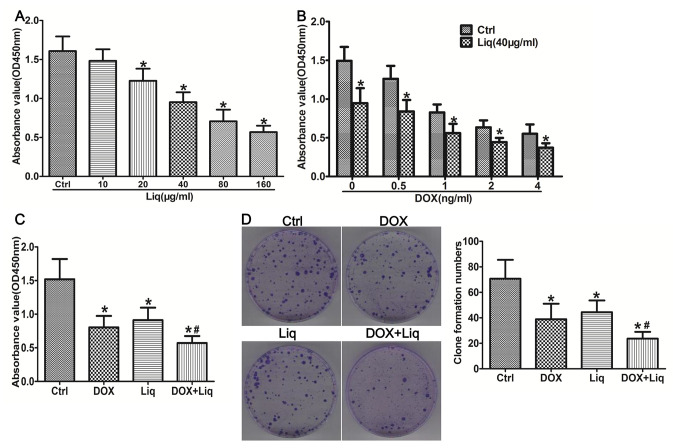

Liq inhibits the proliferation and promotes the sensitization of TNBC cells to DOX treatment

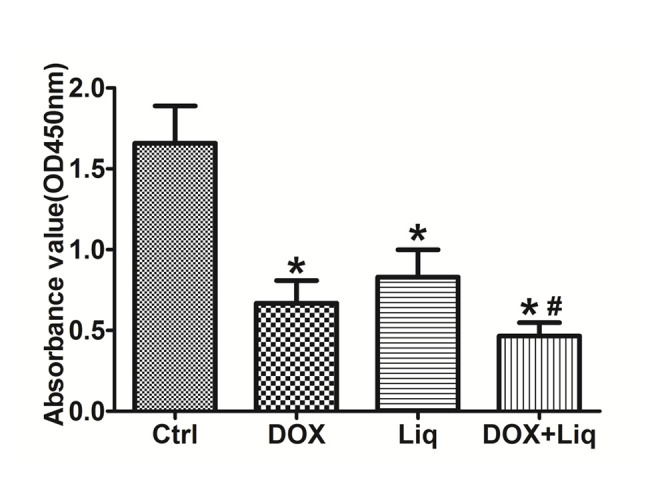

To investigate the role of Liq in regulating the therapeutic response to DOX treatment, the MDA-MB-231 and BT549 TNBC cell lines were used. The CCK-8 assay suggested that the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells decreased in a dose-dependent manner following treatment with different concentrations of Liq for 48 h (Fig. 1A). The results also indicated that Liq concentrations ≥20 µg/ml significantly decreased the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells compared with the control group (Fig. 1A). Therefore, 40 µg/ml Liq (Liq IC50=69.28 µg/ml) was used for subsequent experiments. Additionally, the effects of DOX and combination treatment (1 ng/ml DOX and 40 µg/ml Liq) on the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells were assessed. DOX treatment alone did not significantly alter the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells compared with the negative control group. By contrast, the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells was significantly decreased by the combination treatment, even with low concentrations of DOX, compared with the negative control group (DOX IC50 combination treated group =0.60 ng/ml vs. DOX IC50 DOX treated group =1.72 ng/ml; Fig. 1B). Compared with the control group, DOX (1 ng/ml), Liq (40 µg/ml) and combination treatment (1 ng/ml DOX and 40 µg/ml Liq) significantly reduced the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells. Furthermore, combination treatment (1 ng/ml DOX and 40 µg/ml Liq) significantly decreased the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells compared with DOX treatment alone (1 ng/ml) (P<0.05; Fig. 1C). Compared with the control group, the number of cell colonies was found to be significantly reduced in both DOX-treated and Liq-treated groups, whilst he number of cell colonies was significantly decreased in the combination treated group compared with that in the DOX-treated group (P<0.05; Fig. 1D). Similar results were obtained for BT549 cells. DOX (1 ng/ml), Liq (40 µg/ml) and combination treatment (1 ng/ml DOX and 40 µg/ml Liq) significantly reduced the viability of BT549 cells, compared with that in the control group. The viability of BT549 cells was significantly decreased in the combination treatment group, compared with that in the DOX-treated group (P<0.05; Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Liq treatment inhibits the viability and promotes the sensitization of MDA-MB-231 cells to DOX treatment. (A) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with (A) Liq (0-160 µg/ml), (B) DOX (0-4 ng/ml) or a combination of DOX (0-4 ng/ml) and Liq (40 µg/ml), and (C) DOX (1 ng/ml), Liq (40 µg/ml) or a combination of DOX (1 ng/ml) and Liq (40 µg/ml) for 48 h. Subsequently, cell viability was determined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay in triplicate. (D) MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with DOX (1 ng/ml), Liq (40 µg/ml) or a combination of DOX (1 ng/ml) and Liq (40 µg/ml). Subsequently, cell proliferation was assessed using a clone formation assay. Magnification, x100. *P<0.05 vs. the negative control group. #P<0.05 vs. the DOX-treated group. Liq, liquiritigenin; DOX, doxorubicin; OD, optical density; Ctrl, control.

Figure 2.

Liq treatment inhibits the viability and promotes the sensitization of BT549 cells to DOX treatment. BT549 cells were treated with DOX (1 ng/ml), Liq (40 µg/ml) or a combination of DOX (1 ng/ml) and Liq (40 µg/ml) for 48 h. Subsequently, cell viability was determined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay in triplicate. *P<0.05 vs. the negative control group. #P<0.05 vs. the DOX-treated group. Liq, liquiritigenin; DOX, doxorubicin; OD, optical density; Ctrl, control.

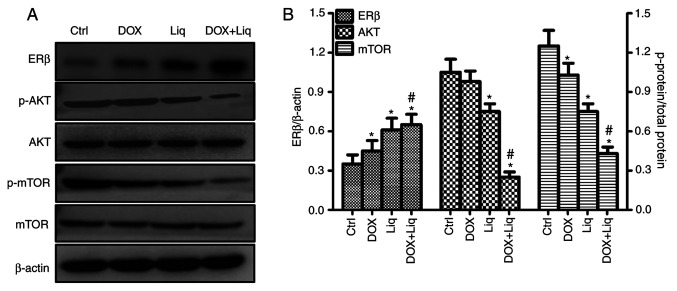

Liq enhances the therapeutic efficacy of DOX by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway

To investigate whether Liq enhanced DOX sensitivity by modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, the protein expression levels of ERβ, p-AKT, AKT, p-mTOR and mTOR were assessed by western blotting in DOX-treated, Liq-treated and combination-treated MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Liq or the combination treatment displayed increased ERβ expression levels, and decreased levels of AKT and mTOR phosphorylation, compared with the control group (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, the ratio of ERβ/β-actin, p-AKT/AKT and p-mTOR/mTOR was calculated. MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Liq or the combination treatment displayed significantly increased expression levels of ERβ, but a significantly decreased ratio of p-AKT/AKT and p-mTOR/mTOR, compared with the control group (Fig. 3B). ERβ expression was significantly increased, and the ratio of p-AKT/AKT and p-mTOR/mTOR was significantly decreased in the combination treatment group compared with the DOX-treated group (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Liq treatment enhances the protein expression of ERβ and inhibits the activity of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in TNBC cells. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with DOX (1 ng/ml), Liq (40 µg/ml) or a combination of DOX (1 ng/ml) and Liq (40 µg/ml). Subsequently, the protein expression levels of ERβ, p-AKT, AKT, p-mTOR and mTOR were (A) determined by western blotting and (B) quantified. ERβ expression levels were increased in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Liq (40 µg/ml) or the combined treatment, whereas the ratio of p-AKT/AKT and p-mTOR/mTOR was decreased, compared with the control group. *P<0.05 vs. the negative control group. #P<0.05 vs. the DOX-treated group. Liq, liquiritigenin; ERβ, estrogen receptor β; DOX, doxorubicin; p, phosphorylated; Ctrl, control.

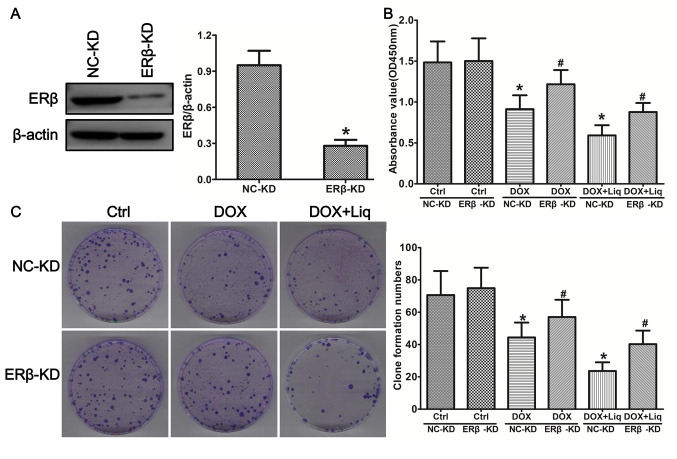

ERβ knockdown inhibits the effects of Liq on proliferation and the therapeutic efficacy of DOX in TNBC cells

To identify the role of ERβ in regulating DOX sensitivity in TNBC cells, ERβ knockdown in MDA-MB-231 cells was performed using lentiviral particles. Subsequently, the viability and proliferation of MDA-MB-231 (ERα-/ERβ+) and ERβ-KD (ERα-/ERβ-) cells were assessed. The protein expression levels of ERβ were significantly decreased in the ERβ-KD group compared with the NC-KD group (Fig. 4A). ERβ-KD-MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Liq (40 µg/ml) or the combination treatment (1 ng/ml DOX and 40 µg/ml Liq) displayed increased cell viability compared with the corresponding NC-KD group (Fig. 4B). The number of cell colonies was also significantly increased in the Liq-treated (40 µg/ml) and combination-treated (1 ng/ml DOX and 40 µg/ml Liq) ERβ-KD groups compared with the corresponding NC-KD groups (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Liq function is ERβdependent. (A) The expression of ERβ in NC-KD and ERβ-KD MDA-MB-231 cells was assessed using western blotting. (B) NC-KD and ERβ-KD MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with Liq (40 µg/ml) or a combination of DOX (1 ng/ml) and Liq (40 µg/ml). Subsequently, cell viability was determined using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. (C) Proliferation of ERβ-KD and NC-KD cells was assessed using a colony formation assay. *P<0.05 vs. the negative control group. P<0.05 vs. the NC-KD group. Liq, liquiritigenin; ERβ, estrogen receptor β; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; NC, negative control; KD, knockdown; DOX, doxorubicin; Ctrl, control; OD, optical density.

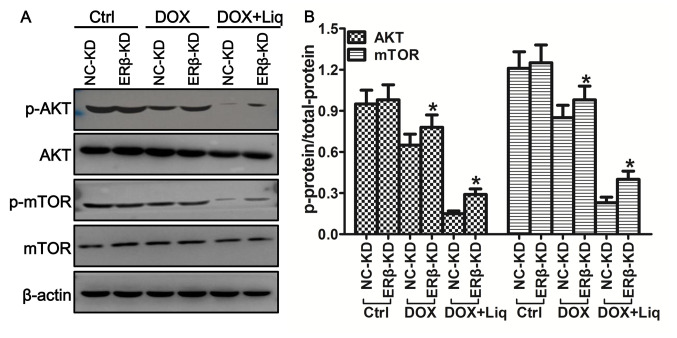

Liq-mediated effects on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway are ERβ-dependent

Western blotting was used to further investigate the relationship between the expression of ERβ and the regulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Liq (40 µg/ml) or the combination treatment (1 ng/ml DOX and 40 µg/ml Liq) displayed significantly decreased expression levels of p-AKT and p-mTOR compared with the control group (Fig. 5A). However, ERβ-KD cells treated with Liq or the combination treatment displayed significantly increased levels of AKT and mTOR phosphorylation compared with the corresponding NC-KD groups (P<0.05; Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

ERβ KD increases the activity of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in MDA-MB-231 cells. Protein expression levels of p-AKT, AKT, p-mTOR and mTOR in NC-KD and ERβ-KD cells were (A) determined by western blotting and (B) the ratio of phosphorylated/total protein was quantified. *P<0.05 vs. the NC-KD group. ERβ, estrogen receptor β; p, phosphorylated; NC, negative control; KD, knockdown; Ctrl, control; Liq, liquiritigenin; DOX, doxorubicin.

Discussion

DOX is one of the most active conventional chemotherapeutic drugs used for breast cancer in neoadjuvant, adjuvant and palliative settings (12,13). DOX, as a cytotoxic agent affiliated with anthracycline, can inhibit DNA and RNA synthesis, topoisomerase II enzymatic activity, and block DNA transcription and replication (14-16). Due to a lack of effective endocrine-based and HER2-targeted therapies, doxorubicin-containing chemotherapy plays an important role in patients with TNBC in an adjuvant setting (17). However, the clinical outcome of conventional chemotherapy is not satisfactory in patients with TNBC, as resistance to standard anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapy results in treatment failure in some cases (18). In the present study, the ERβ specific agonist Liq decreased the proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells and enhanced the cytotoxic chemotherapeutic effects of DOX. Liq is a natural compound isolated from the roots of Glcyrrhizae uralensis (19). Similar to other ERβ specific agonists, including diarylpropionitrile and WAY200070, Liq upregulates ERβ expression and displays inhibitory effects in TNBC cells (20). ERβ-KD-MDA-MB-231 cells treated with the combination treatment did not display increased sensitivity to DOX compared with ERβ-positive cells. The results suggested that the synergistic effect of DOX and Liq in TNBC was dependent on ERβ. ERβ activation caused by Liq does not induce cell apoptosis and proliferation of TNBC cells, but does contribute to cell cycle arrest (21). In 2017, Reese et al reported that the activation of ERβ resulted in the decreased expression of a number of cell cycle-related genes, including cyclin B and cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), both in vitro and in vivo (22). The inhibition of CDK1 induced G2/M phase cell cycle arrest, which led to decreased proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells (22). Collectively, the aforementioned studies suggest that doxorubicin and ERβ agonists display synergistic antitumor activity in TNBC, which provides strong rationale for the combined use of ERβ agonists and conventional chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of TNBC.

A number of previous studies investigating TNBC have focused on the therapeutic value of ERβ in endocrine therapy, or the role of ERβ in tumor invasion and metastasis. For example, Hinsche and Girgert (21) co-cultured MG63 osteoblast-like cells with the HCC1806 TNBC cell line (ERα-/ERβ+), and reported that the ERβ agonists Liq and ERB-041 increased the expression of ERβ, and inhibited bone-directed invasion. Thomas et al (23) reported that ERβ1 inhibits EMT and invasion in TNBC cells in vitro and in vivo. The present study further suggested that the ERβ agonist Liq increased the sensitivity of TNBC cells to conventional chemotherapeutic agents. ERβ agonist-induced chemical sensitization has also been observed in various types of malignant tumors, including TNBC (24). Furthermore, Liu et al suggested that Liq treatment increased the susceptibility of glioma cells to temozolomide by inhibiting the mTOR signaling pathway (25).

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway plays a critical role in regu-lating cell metabolism, growth, survival, proliferation, migration and differentiation (26). The inappropriate activation or overactivation of the signaling pathway can result in the progression of tumors in several malignancies, including TNBC (27,28). AKT interacts with the DNA-protein kinase catalytic subunit and induces DNA double-strand break repair (29). In TNBC, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway serves as an oncogenic driver (30). PI3K mutations were reported in 73.9% cfDNA samples and 57.1% tumor samples obtained from patients with metastatic TNBC (31). In addition, overexpression of PI3K and overactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway are associated with chemical drug resistance in breast cancer cells (32,33). Therefore, some have hypothesized that combined treatment, including standard chemotherapy and specifically target components of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway could be used to effectively treat TNBC (31). However, Park et al (31) previously found that the addition of the mTOR inhibitor everolimus to the gemcitabine/cisplatin treatment strategy did not result in a synergistic effect in patients with metastatic TNBC. In addition, the toxicities of everolimus, including stomatitis and hematologic toxicities, should be considered (31,34). The identification of other inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, which display increased tolerance and decreased toxicity, is essential for the effective treatment of TNBC. The present study suggested that increased ERβ expression levels decreased the level of AKT and mTOR phosphorylation in TNBC cells. The result was consistent with a previous study, which reported that ERβ1+/pAKT- status in TNBC tumor samples predicted the most favorable prognosis. The previous study also suggested that ERβ activation was associated with inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway (11). An explanation for the association could be that increased ERβ expression results in decreased cell proliferation, which is primarily controlled by the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in TNBC cells (35). Furthermore, downregulation of the signaling pathway results in decreased cell proliferation (35). Alternatively, the ERβ-mediated inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway may be associated with downstream actions that influence the secretion of amphiregulin and Wnt-10b, which may form part of a cascade that could potentially regulate the signaling pathway (36). However, the mechanism underlying how ERβ activation modulates the activity of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway requires further investigation. Therefore, Liq, which can specifically target ERβ-positive cells, displays characteristics of a therapeutic agent with improved tolerance and reduced toxicity. Furthermore, Liq may display increased specificity compared with general PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway inhibitors, which could result in improved patient outcomes when used in combination with chemotherapy. To conclude, the in vitro results of the present study suggested that Liq increased the sensitivity of TNBC cells to DOX, and indicated that ERβ agonists in combination with chemotherapy may serve as a novel therapeutic strategy for TNBC. Additionally, Liq enhanced the sensitivity of TNBC cells to DOX by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, in an ERβ-dependent manner.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Health and Family Planning Commission of Hunan Province (grant no. 20180726), and the Ren Shu Foundation from Hunan Provincial People's Hospital (grant no. RS201707).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

SL, PF and AW designed the study. SL, YJ and MF performed the experiments. MW, CZ, SH and ZH analyzed the data. SL and AW drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938–1948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papa A, Caruso D, Tomao S, Rossi L, Zaccarelli E, Tomao F. Triple-negative breast cancer: Investigating potential molecular therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19:55–75. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.970176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oakman C, Viale G, Di Leo A. Management of triple negative breast cancer. Breast. 2010;19:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. New Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938–1948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, Lickley LA, Rawlinson E, Sun P, Narod SA. Triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429–4434. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imamov O, Lopatkin NA, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor beta in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2773–2774. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200412233512622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors: Therapies targeted to receptor subtypes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:44–55. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JQ, Russo J. ER alpha-negative and triple negative breast cancer: Molecular features and potential therapeutic approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1796:162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakamoto G, Honma N. Estrogen receptor beta status influences clinical outcome of triple negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2009;16:281–282. doi: 10.1007/s12282-009-0110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Zhang C, Chen K, Tang H, Tang J, Song C, Xie X. ERβ1 inversely correlates with PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway and predicts a favorable prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152:255–269. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Minckwitz G, Raab G, Caputo A, Schütte M, Hilfrich J, Blohmer JU, Gerber B, Costa SD, Merkle E, Eidtmann H, et al. Doxorubicin with cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel every 21 days compared with doxorubicin and docetaxel every 14 days as preoperative treatment in operable breast cancer: The GEPARDUO study of the German Breast Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2676–2685. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gasparini G, Dal Fior S, Panizzoni GA, Favretto S, Pozza F. Weekly epirubicin versus doxorubicin as second line therapy in advanced breast cancer. A randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 1991;14:38–44. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199102000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Momparler RL, Karon M, Siegel SE, Avila F. Effect of adriamycin on DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis in cell-free systems and intact cells. Cancer Res. 1976;36:2891–2895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fornari FA, Randolph JK, Yalowich JC, Ritke MK, Gewirtz DA. Interference by doxorubicin with DNA unwinding in MCF-7 breast tumor cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:649–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tewey KM, Rowe TC, Yang L, Halligan BD, Liu LF. Adriamycin-induced DNA damage mediated by mammalian DNA topoisomerase II. Science. 1984;226:466–468. doi: 10.1126/science.6093249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mamounas EP, Bryant J, Lembersky B, Fehrenbacher L, Sedlacek SM, Fisher B, Wickerham DL, Yothers G, Soran A, Wolmark N. Paclitaxel after doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide as adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer: Results from NSABP B-28. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3686–3696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan Y, Li M, Ma K, Hu Y, Jing J, Shi Y, Li E, Dong D. Dual-target MDM2/MDMX inhibitor increases the sensitization of doxorubicin and inhibits migration and invasion abilities of triple-negative breast cancer cells through activation of TAB1/TAK1/p38 MAPK pathway. Cancer Biol Ther. 2019;5:617–632. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2018.1539290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shanle EK, Hawse JR, Xu W. Generation of stable reporter breast cancer cell lines for the identification of ER subtype selective ligands. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:1940–1949. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reese JM, Suman VJ, Subramaniam M, Wu X, Negron V, Gingery A, Pitel KS, Shah SS, Cunliffe HE, McCullough AE, et al. ERβ1: Characterization, prognosis, and evaluation of treatment strategies in ERα-positive and -negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(749) doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinsche O, Girgert R, Emons G, Gründker C. Estrogen receptor β selective agonists reduce invasiveness of triple-negative breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:878–884. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reese JM, Bruinsma ES, Monroe DG, Negron V, Suman VJ, Ingle JN, Goetz MP, Hawse JR. ERβ inhibits cyclin dependent kinases 1 and 7 in triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:96506–96521. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas C, Rajapaksa G, Nikolos F, Hao R, Katchy A, McCollum CW, Bondesson M, Quinlan P, Thompson A, Krishnamurthy S, et al. ERbeta1 represses basal-like breast cancer epithelial to mesenchymal transition by destabilizing EGFR. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(R148) doi: 10.1186/bcr3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shanle EK, Zhao Z, Hawse J, Wisinski K, Keles S, Yuan M, Xu W. Research resource: Global identification of estrogen receptor β target genes in triple negative breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1762–1775. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Wang L, Chen J, Ling Q, Wang H, Li S, Li L, Yang S, Xia M, Jing L. Estrogen receptor β agonist enhances temozolomide sensitivity of glioma cells by inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:1516–1522. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan KH, Yap TA, Yan L, Cunningham D. Targeting the PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling network in cancer. Chin J Cancer. 2013;32:253–265. doi: 10.5732/cjc.013.10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bitting RL, Armstrong AJ. Targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:R83–R99. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martelli AM, Evangelisti C, Chiarini F, McCubrey JA. The phosphate-dylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mTOR signaling network as a therapeutic target in acute myelogenous leukemia patients. Oncotarget. 2010;1:89–103. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toulany M, Lee KJ, Fattah KR, Lin YF, Fehrenbacher B, Schaller M, Chen BP, Chen DJ, Rodemann HP. Akt promotes post-irra-diation survival of human tumor cells through initiation, progression, and termination of DNA-PKcs-dependent DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:945–957. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costa RLB, Han HS, Gradishar WJ. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in triple-negative breast cancer: A review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;169:397–406. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4697-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park IH, Kong SY, Kwon Y, Kim MK, Sim SH, Joo J, Lee KS. Phase I/II clinical trial of everolimus combined with gemcitabine/cisplatin for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Cancer. 2018;9:1145–1151. doi: 10.7150/jca.24035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chock KL, Allison JM, Shimizu Y, ElShamy WM. BRCA1-IRIS overexpression promotes cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8782–8791. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Brien NA, Browne BC, Chow L, Wang Y, Ginther C, Arboleda J, Duffy MJ, Crown J, O'Donovan N, Slamon DJ. Activated phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT signaling confers resistance to trastuzumab but not lapatinib. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1489–1502. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu J, Tian D. Hematologic toxicities associated with mTOR inhibitors temsirolimus and everolimus in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:67–74. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2013.844116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton N, Márquez-Garbán D, Mah V, Fernando G, Elshimali Y, Garbán H, Elashoff D, Vadgama J, Goodglick L, Pietras R. Biologic roles of estrogen receptor-β and insulin-like growth factor-2 in triple-negative breast cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015(925703) doi: 10.1155/2015/925703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.