Abstract

Anthracyclines are commonly used anticancer drugs with well-known and extensively studied cardiotoxic effects in humans. In the clinical setting guidelines for assessing cardiotoxicity are well-established with important therapeutic implications. Cardiotoxicity in terms of impairment of cardiac function is largely diagnosed by echocardiography and based on objective metrics of cardiac function. Until this day, cardiotoxicity is not an endpoint in the current general toxicology and safety pharmacology preclinical studies, although other classes of drugs apart from anthracyclines, along with everyday chemicals have been shown to manifest cardiotoxic properties. Also, in the relevant literature there are not well-established objective criteria or reference values in order to uniformly characterize cardiotoxic adverse effects in animal models. This in depth review focuses on the evaluation of two important echocardiographic indices, namely ejection fraction and fractional shortening, in the literature concerning anthracycline administration to rats as the reference laboratory animal model. The analysis of the gathered data gives promising results and solid prospects for both, defining anthracycline cardiotoxicity objective values and delineating the guidelines for assessing cardiotoxicity as a separate hazard class in animal preclinical studies for regulatory purposes.

Keywords: anthracyclines, echocardiography, ejection fraction, fractional shortening, rats

Introduction

Chemotherapeutics cardiotoxicity is a major concern for clinicians treating different kinds of cancer, as it seriously affects their treatment options and the survival of the patient. The cut-off values for the identification of cardiotoxicity caused by chemotherapeutics in humans differ between the American and European guidelines: the definition considers a lower cut-off value of normality for the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 50% in Europe (1) and 53% in the USA (2). Both Guidelines emphasize that a drop of LVEF compared to the patient's previous values is also required. This definition is crucial for patients and clinicians, as patients presenting this decline in cardio-imaging indices of cardiac function should be treated with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) in combination with β-blockers (3); nevertheless, modifications of anticancer treatment in such patients remain a matter of discussion among different specialists.

In animal studies, where new anticancer substances are evaluated and different agents are tested to overcome anticancer drugs cardiotoxicity, identification of the extent of cardiotoxicity is crucial and necessary for the evaluation of any favourable effects of the counteracting agent (4). In this regard, cardiac imaging is more often used at analogy to the clinical setting. Biomarkers and clinical signs of heart failure are also taken into consideration, but cardiac imaging in animal studies has gained momentum.

Anthracyclines are a class of drugs used in cancer chemotherapy isolated from Streptomyces bacterium. These compounds are used to treat many cancers, including leukemias, lymphomas, as well as breast, stomach, uterine, ovarian, bladder cancer, and lung cancers (5–7). The first anthracycline discovered was daunorubicin (trade name Daunomycin), which is produced naturally by Streptomyces peucetius, a species of actinobacteria. Clinically, the most important anthracyclines are doxorubicin, daunorubicin, epirubicin and idarubicin. Anthracyclines, which are considered as well-established cardiotoxic compounds causing myocardial suppression in a considerable number of patients, are also used in animal studies as an easy and low-cost method to introduce a model of dilated cardiomyopathy (8), as opposed to interventional research animal models of infarction and myocardial ischaemia [e.g., permanent ligation of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) or cryo-pen application on the surface of the heart leading to cryo-scar ischemia]. Different animal species and various anthracyclines dosing and administration schemes have been applied in the literature for the development of anthracyclines cardiotoxicity (9) and monitoring of the progress thereof, as well as testing different compounds/schemes for ameliorating myocardial damage. To monitor cardiotoxicity caused by anthracyclines, cardiac imaging is primarily used and secondarily, biochemical markers.

At the same time, other pharmaceutical compounds, such as anabolic steroids, along with everyday chemicals, such as metals and pesticides, have been implicated to adversely affect cardiac pathology causing function impairment (10). Toxicity and risk for human health posed by chemicals are well controlled at a European level through a thoroughly developed regulatory network. Nevertheless, cardiotoxicity is not described as a separate hazard class and no specific classification criteria are available in order to legally classify chemicals well in advance as cardiotoxic and avoid potential long-term cardiovascular complications, which could significantly burden any national health system.

But, what is considered cardiotoxicity of anticancer agents and specifically anthracyclines when parameters of cardiac imaging are monitored in animal studies? Is there a uniformity in animal models of anthracyclines cardiotoxicity induction and most importantly, do all studies describe the same decline of myocardial function? Addressing these issues could be of wider use both in clinical medicine and practice, when assessing agents employed for salvation to cardiotoxic complications during oncology treatment, for example, as well as to regulators, when trying to establish reference values in echocardiographic function representing cardiotoxicity induced in animals by chemicals.

In the current in depth review, the identification of most commonly used metrics of myocardial function in animal studies of anthracycline induced cardiotoxicity are presented, along with the range of these values differentiating normal cardiac function from animals with pathological echocardiographic findings indicative of anthracycline cardiotoxicity as per author presentation.

Materials and methods

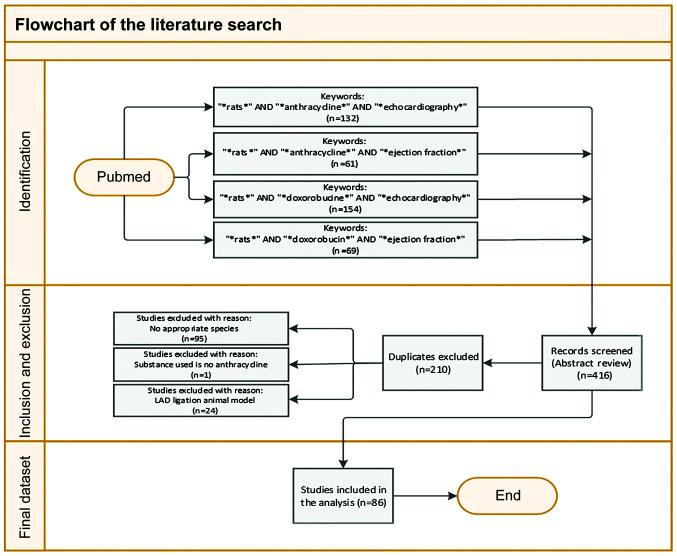

PubMed electronic database was systematically searched to detect all original research studies published until March 1, 2020, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (11). The specific literature search strategy used was: [AND (“*rats*” OR “*doxorubicin* OR “*echocardiography*” OR “anthracycline” OR “*ejection fraction*”)] either in the Title, or the Abstracts. The reference list of the retrieved studies was further evaluated for the relevance of the subject and the eligibility by screening the titles/abstracts of full papers. The non-English citations (<5) were reviewed separately. Animal data only from rat species were assessed, as it is evident from the search string. All types of citations other than original research studies (e.g., review articles) were excluded. Two authors (NG and CT) independently assessed the title and the abstract content (or both) of each record retrieved to decide which studies should be further evaluated and extracted all data. Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by consultation with a third author (KT). A final draft of the manuscript was prepared after several revisions and approved by all authors. In total, 86 published manuscripts on animal studies were considered for the systematic review (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma flow chart (literature search) for the present study design.

Despite the small size of the rat heart and the fast heart rate, echocardiography is systematically used in the evaluation of rat heart function (12). Data for 2 main indices of LV contractility were extracted from the list of studies.

The first index is LV fractional shortening (FS) and is calculated by the formula: FS (%) = [LV end-diastolic diameter (LVDd) minus LV end-systolic diameter (LVDs)]/LVDd × 100.

LVEF is the second and more common, index of LV contractility. EF can be calculated from the equation: EF (%) = [(LVDd3 - LVDs3) / LVDd3] × 100 (13) or from the equation: EF (%) = (LVEDV-LVESV)/LVEDV × 100, where LVEDV is the LV end-diastolic volume and LVESV is LV end-systolic volume (12).

Results

A summary of the studies reviewed in the present report is presented in Table I.

Table I.

Treatment protocol and main findings of the studies that examined anthracyclines cardiotoxicity in rats reviewed in the present report.

| Publication | No. of animals/rat strain/sex | Anthracycline administered | Anthracycline total dose | Duration | Summary of findings | Calculations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al (14) | 30/Sprague Dawley | Doxorubicin | 1 mg/kg | Daily doses | Cardiac dysfunction | Values calculated | |

| rats/male | (brand name Adriamycin) | for 2 weeks | (parameters monitored: | manually by the | |||

| diastolic left ventricular | authors of this | ||||||

| internal dimension, systolic | review | ||||||

| left ventricular internal | |||||||

| dimension, LVEF and LVFS) | |||||||

| Tian et al (15) | 70/Sprague Dawley | Doxorubicin | 3.0 mg/kg | Once a week | Cardiomyopathy | Values provided | |

| rats/Male | for 6 weeks | in the manuscript | |||||

| Andreadou et al (16) | 90/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 18 mg/kg, ip | 6 equal doses | Cardiomyopathy | Values provided | |

| for 2 weeks | (parameters monitored: | in the manuscript | |||||

| cardiac geometry, function | |||||||

| and histopathology) | |||||||

| Oliveira et al (17) | 20/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 5 mg/kg, ip | Once a week | Ventricular dysfunction | Values provided | |

| for 4 weeks | in the manuscript | ||||||

| Hydock et al (18) | 46/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 10 mg/kg ip | Acute | Parameters altered: | Values provided | |

| rats/Male | administration | LVFS and LVPWT | in the manuscript | ||||

| (bolus) | |||||||

| Fernandez-Fernandez | 36/Sprague-Dawley rats | Doxorubicin | 18 mg/kg | Over 12 days | Cardiac function altered | Values provided | |

| et al (19) | Wistar rats Fischer-344 | (LVFS, left ventricular | in the manuscript | ||||

| rats/NM | developed pressure, | ||||||

| contractility and relaxation, | |||||||

| cardiac capillary permeability) | |||||||

| Todorova et al (20) | 27/Fisher 344 rats/female | Doxorubicin | 12 mg/kg | Twice per week | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| (1.5 mg/kg each) | for 4 weeks | Plasma levels of troponin I | in the manuscript | ||||

| Left ventricle (LV) function, | |||||||

| LV PWT, LV volume, | |||||||

| LVEF, LVFS | |||||||

| Vasić et al (21) | 68/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 15 mg/kg ip | Every other day | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| for 2 weeks | Echocardiography, | in the manuscript | |||||

| serum cardiac troponins, | |||||||

| heart rate variability and | |||||||

| blood pressure variability | |||||||

| Mathias et al 22) | 64/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 20 mg/kg ip | Acute administration | Altered LVFS | Values provided | |

| (a single injection) | in the manuscript | ||||||

| Wang et al (23) | 40/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 15 mg/kg ip | Acute administration | Altered LVEF, LVFS | Values calculated | |

| rats/male | (brand name Adriamycin) | (a single injection) | and LV outflow | manually by the | |||

| authors of this | |||||||

| review | |||||||

| Arozal et al (24) | 25/Sprague-Dawley | Daunorubicin | 3 mg/kg/day | Every other day | Altered cardiac function | Values provided | |

| rats/male | (18 mg/kg total dose) | for 12 days | (haemodynamic status | in the manuscript | |||

| and echocardiography) | |||||||

| Argun et al (25) | 40/10-week-old | Doxorubicin | 4 mg/kg/dose to | Twice a week | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| Wistar albino rats/male | a cumulative dose | for 2 weeks | Serum BNP and C-type | in the manuscript | |||

| of 16 mg/kg, ip | natriuretic peptide | ||||||

| LV functions by | |||||||

| echocardiography | |||||||

| and histological | |||||||

| assessment | |||||||

| Tatlidede et al (26) | 32/Wistar albino rats of | Doxorubicin | 20 mg/kg, ip | Every other day | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| both sexes | for 2 weeks | BP and HR, | in the manuscript | ||||

| echocardiography | |||||||

| Lactate dehydrogenase | |||||||

| Razmaraii et al (27) | 24/adult Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg/48 h | Over a 12-day period | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| LVSP, LVDP, rate of | in the manuscript | ||||||

| rise/drop of LV pressure, | |||||||

| LVEF, LVFS, contractility | |||||||

| Gziri et al (28) | 43/ pregnant Wistar | Doxorubicin | 10 or 20 mg/kg i.v. | On 18th day of | Altered left ventricular | Values provided | |

| rats/female | pregnancy | function | in the manuscript | ||||

| Oliveira et al (29) | 29/adult Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | Accumulated doses of | Four weekly | Myocardial fibrosis | Values provided | |

| 8 (n=8), 12 (n=7), and | injections | Altered left ventricular | in the manuscript | ||||

| 16 (n=7) mg/kg, ip | over 8 weeks | systolic function | |||||

| Carvalho et al (30) | 64/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 20 mg/kg, ip | Acute | LVEF monitored | Values provided | |

| administration | in the manuscript | ||||||

| (a single injection) | |||||||

| Stewart et al (31) | 72/Sprague Dawley | Doxorubicin | 15 mg/kg, ip | Acute administration | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | (a bolus injection) | LV septal and PWT, | in the manuscript | ||||

| LVESd, LVEDd, mitral | |||||||

| and aortic valve blood | |||||||

| flow profiles, heart dimensions | |||||||

| Polegato et al (32) | 35/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 20 mg/kg, ip | Acute administration | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| (a single dose) | LVFS, isovolumetric | in the manuscript | |||||

| relaxation time and | |||||||

| myocardial passive stiffness | |||||||

| Lee et al (33) | 20/Sprague Dawley rats/male | Doxorubicin | Cumulative dose: | Once every two days | Impaired LV function | Values calculated | |

| 20 mg/kg, ip | for 6 times | and performance | manually by the | ||||

| authors of this | |||||||

| review | |||||||

| Cheah et al (34) | 29/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 5 mg/kg, iv | Acute administration | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| (a single dose) | BP, HR, LVED volume, | in the manuscript | |||||

| other echocardiographic | |||||||

| parameteres | |||||||

| Li et al (35) | 48/adult Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | Cumulative dose: | Over a 4-week period | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | 16 mg/kg, ip | serum BNP level | in the manuscript | ||||

| LVEDd, LVESd, LVEF, LVFS | |||||||

| Dundar et al (36) | 28/adult Wistar albino | Doxorubicin | 15 mg/kg, ip | Acute administration | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/female | (a single dose) | LVIDd and LVISd | in the manuscript | ||||

| via the parasternal long | |||||||

| axis two-dimensional images. | |||||||

| LVFS and LVEF | |||||||

| Barış et al (37) | 31/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 25 mg/kg, ip | For 12–14 days | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | left ventricular ejection f | in the manuscript | |||||

| raction (LVEF), LVFS and | |||||||

| mitral lateral annulus (s’) | |||||||

| velocity + left ventricular | |||||||

| end-diastolic and end-systolic | |||||||

| diameters | |||||||

| Lu et al (38) | 60/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5mg/kg/week, ip | For 6 weeks | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | LVFS and LVEF | in the manuscript | |||||

| O'Connell et al (39) | 115/adult Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 6 doses over a period | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| (cumulative dose | of 2 weeks | left ventricular systolic | in the manuscript | ||||

| 15 mg/kg) | and diastolic dimensions and | ||||||

| 2 mg/kg, ip (cumulative | Once a week | EF | |||||

| dose 18 mg/kg) | for 9 weeks | ||||||

| Chang et al (40) | 71/Sprague-Dawley rats/nm | Doxorubicin | 3 mg/kg/day, iv | Once a week | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| for 6 weeks | SWT and PWT, LVED | in the manuscript | |||||

| dimensions, LVES dimensions, | |||||||

| LVEF | |||||||

| Teng et al (41) | 46/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg, ip | Once a week for 8 | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | weeks | LVED dimensions, LVES | in the manuscript | ||||

| dimensions, FS | |||||||

| Kim et al (42) | 61/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 1.25 mg/kg, ip | Every other day for | LV systolic/diastolic | Values provided | |

| rats/male | 1 month (16 times) | dysfunction | in the manuscript | ||||

| Kondru et al (43) | 24/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg, ip | Once in a week | Myocardial dysfunction | Values calculated | |

| for 5 weeks | manually by the | ||||||

| authors of this | |||||||

| review | |||||||

| Moriyama et al (44) | 66/Crl:CD(SD) rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg, iv | Once weekly, | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| for 6 weeks | LVEDd, LVESd, LVFS | in the manuscript | |||||

| Burdick et al (45) | 20/Crl:CD(SD) rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg, ip | Once a week | Parameters monitored: | Values calculated | |

| for 6 weeks | LVFS | manually by the | |||||

| authors of this | |||||||

| review | |||||||

| Ammar et al (46) | 50/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 3 times a week | Parameters monitored: | Values calculated | |

| for 2 weeks | LVED dimensions | manually by the | |||||

| and LVSD dimensions, FS | authors of this | ||||||

| review | |||||||

| Calvé et al (47) | 21/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 3 mg/kg | Acute administration | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/female | (on postnatal | IVSd, LVPWd, LVIDd, | in the manuscript | ||||

| day 26th) | LVISd | ||||||

| Shen et al (48) | 150/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 1 mg/kg, ip | Twice a week | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rat/male | 2 mg/kg, ip (cumulative | Once a week | LVESd, LVEDd, LVEF | in the manuscript | |||

| dose 12 mg/kg) | for 6 weeks | ||||||

| Wu et al (49) | 32/Sprague-Dawley rat/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Every second day | Parameters monitored: | Values calculated | |

| (cumulative dose | for 6 times | LVEDP, LVESP and left | manually by the | ||||

| 15 mg/kg) | ventricular pressure | authors of this | |||||

| (±dP/dtmax), LVEF and LVFS | review | ||||||

| Shoukry et al (50) | 32/Wister rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 2 weeks | Parameters monitored: | Values calculated | |

| LVIDd, LVIDs, LVFS and | manually by the | ||||||

| LVEF | authors of this | ||||||

| review | |||||||

| Niu et al (51) | 26/Sprague Dawley | Doxorubicin | Each dose consisted of | For 2 weeks on days | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4 | 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, | IVSd, IVSs, LVPWd and | in the manuscript | |||

| and 4 mg/kg, ip | 9th, 11th, 13th and | LVPWs, LVIDd, LVIDs | |||||

| (cumulative dose | 15th, respectively | were measured on left | |||||

| 20 mg/kg) | ventricular long-axis areas. | ||||||

| LVEF and LVFS | |||||||

| Boutagy et al (52) | 20/Wistar rats | Doxorubicin | 2.15 mg/kg, ip | Every 3 days | Impaired systolic function and | Values calculated | |

| (Crl:Wl)/male | (cumulative dose | for 21 days | LV volumes and dimensions. | manually by the | |||

| 15 mg/kg) | Parameters monitored: | authors of this | |||||

| echocardiographic variables | review | ||||||

| (LVEF, global longitudinal strain, | |||||||

| global radial strain, LVEDV, | |||||||

| LVESV, relative PWT | |||||||

| Lee et al (53) | 150/Fischer rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Every other day | Altered LV function | Values calculated | |

| (cumulative dose | for 2 weeks | Parameters monitored: | manually by the | ||||

| 15 mg/kg) | LVFS, LVEDd and LVESd, | authors of this | |||||

| LV end diastolic volume | review | ||||||

| (LVEDV), right basal | |||||||

| ventricular diastolic diameter | |||||||

| (RVD1), and the RV fractional | |||||||

| area change (RVFAC) | |||||||

| da Silva et al (54) | 52/Wistar rats/female | Doxorubicin | 1.25 mg/kg, ip | Three times a week | Parameters monitored: | Values calculated | |

| for 2 weeks | aorta-to-left atrial diameter | manually by the | |||||

| ratio, LVESd, LVEF | authors of this | ||||||

| review | |||||||

| Mao et al (55) | 160/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg, ip | Once a week for | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | 8 consecutive weeks | LVEDd, LVESd, LVPWT, | in the manuscript | ||||

| interventricular septum | |||||||

| thickness (IVST), LVEF, LVFS | |||||||

| Deng et al (56) | 42/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 6 injections | Parameters monitored: | Values calculated | |

| rats/male | (brand name Adriamycin) | (cumulative 15 mg/kg) | over 2 weeks | LV dimensions, LVFS, LVEF | manually by the | ||

| authors of this | |||||||

| review | |||||||

| Bertinchant et al (57) | 45/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 1.5 mg/kg, iv, | Once a week for | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| (cumulative dose | up to 8 weeks | LVEDd, LVESd and LVFS | in the manuscript | ||||

| 12 mg/kg) | |||||||

| Sun et al (58) | 70/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Once a week for | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | 6 consecutive weeks | LVEF, LVEDd, LVESd | in the manuscript | ||||

| and LVFS | |||||||

| Guerra et al (59) | 12/SHR rats/male | Doxorubicin | 1.5 mg/kg, ip | Once a week | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| (cumulative dose | for 9 weeks | LVEDd, LVESd and LVEF | in the manuscript | ||||

| 13.5 mg/kg) | |||||||

| Gao et al (60) | 90/Wistar albino rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg, ip | Every 3 days | Parameters monitored: | Values calculated | |

| for 30 days | The interventricular septal | manually by the | |||||

| thickness at diastole, left | authors of this | ||||||

| ventricular internal diameter | review | ||||||

| in diastole and systole, | |||||||

| LVPWd at diastole, EF, FS | |||||||

| Chen et al (61) | 60/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 6 injections | Parameters monitored: | Values calculated | |

| rats/male | over 2 weeks | LVAW, LVPWT, LVIDd | manually by the | ||||

| were measured in systole | authors of this | ||||||

| and diastole. | review | ||||||

| EF, FS and LV volume at | |||||||

| end-systole and end-diastole | |||||||

| Li et al (62) | 56/Sprague-Dawley | Epirubicin | 8 mg/kg, ip | Every five days for | Parameters monitored: | Values calculated | |

| rats/male | a total of three | LV dimensions and wall | manually by the | ||||

| injections | thickness, EF, FS | authors of this | |||||

| review | |||||||

| Schwarz et al (8) | 60/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, iv | Once a week | Left ventricular end-systolic | Values provided | |

| rats/female | (brand name Adriamycin) | for 10 weeks | and end-diastolic diameters, FS | in the manuscript | |||

| Leontyev et al (63) | 46/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Once a week | LV end-systolic diameter | Values provided | |

| rats/male | for 9 weeks | (LVESD) and LV end-diastolic | in the manuscript | ||||

| diameter (LVEDD) + FS | |||||||

| Merlet et al (64) | 158/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5mg/kg, ip | 6 injections | LV end-diastolic and -systolic | Values calculated | |

| rats/male | (total 15 mg/kg) | over 2 weeks | diameters (LVEDD and | manually by the | |||

| LVESD), diastolic posterior | authors of this | ||||||

| wall thicknesses (dPWth). | review | ||||||

| + LV end diastolicand systolic | |||||||

| volumes (LVEDV and VESV) | |||||||

| to assess LV ejection fraction | |||||||

| (LVEF), whereas LV shortening | |||||||

| fraction (LVSF) | |||||||

| Ozkanlar et al (65) | 40/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, iv | Once a week | Left ventricular ejection | Values provided | |

| rats/male | for 3 weeks | fraction (LVEF) and left | in the manuscript | ||||

| ventricular fractional shortening | |||||||

| (LVFS) | |||||||

| Hong et al (66) | 12/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 5 mg/ week | Once a week | FS and ejection fraction + | Values provided | |

| rats/male | (brand name Adriamycin) | for 3 weeks | interventricular septal | in the manuscript | |||

| dimension diastole; LV | |||||||

| internal dimension diastole; | |||||||

| LV posterior wall dimension | |||||||

| diastole; interventricular | |||||||

| septal dimension systole; | |||||||

| LV internal dimension | |||||||

| systole; LV posterior | |||||||

| wall dimension systole | |||||||

| Teraoka et al (67) | 75/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 1 mg/kg, ip | 15 times over a | LV diameter of the systole | Values provided | |

| (brand name Adriamycin) | (cumulative dose | period of 3 weeks | LVDs + LV diameter of | in the manuscript | |||

| 15 mg/kg) | the diastole LVDd. | ||||||

| + %fractional shortening | |||||||

| Hamed et al (68) | 130/Wistar rats | Doxorubicin | Cumulative dose of | 3 weeks | LV diameter | Values provided | |

| (Harlan)/male | 15 mg/kg | in systole (LVIDs) | in the manuscript | ||||

| LVIDd, LV diameter in diastole; | |||||||

| IVSd, intra ventricular septum | |||||||

| in diastole | |||||||

| LV posterior wall thickness | |||||||

| in diastole (LVPWd) | |||||||

| Gabrielson et al (69) | 21/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | Cumulative dose of 15 | Six or three weekly | Interventricular septum | Values calculated | |

| rats/female | or 7.5 mg/kg | doses, respectively | diastole (IVSd) and | manually by the | |||

| left ventricular posterior | authors of this | ||||||

| wall thickness at end diastole | review | ||||||

| (PWTED) | |||||||

| + LV chamber diameters were | |||||||

| measured at the end of diastole | |||||||

| (LVEDd) and systole | |||||||

| (LVESd). EF% | |||||||

| Yu et al (70) | 63/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Once a week | LV shortening (LVFS) was | Values provided | |

| rats/male | for 6 weeks | calculated as (LVEDd- | in the manuscript | ||||

| LVESd)/LVEDd 9 100, | |||||||

| where LVEDd is LV | |||||||

| end-diastolic diameter and | |||||||

| LVESD is LV end-systolic | |||||||

| diameter | |||||||

| + LV ejection fraction | |||||||

| Bai et al (71) | Rats | Doxorubicin | 6 injections total | Within 2 weeks | LVEF; LVFS; LVEDd | Values provided | |

| 15 mg/kg) | and LVESd | in the manuscript | |||||

| Lu et al (72) | 48/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 1 mg/kg on the 2nd and | LV internal end-diastolic | Values calculated | ||

| rats/male | 4th days, 2 mg/kg on the | diameter (diastolic LVID) | manually by the | ||||

| 6th and 8th days, | and the posterior wall | authors of this | |||||

| 3 mg/kg on the 10th | end-diastolic thickness | review | |||||

| and 12th days, and | (diastolic LVPW) + LV | ||||||

| 4 mg/kg on the 14th | diastolic volume (diastolic | ||||||

| and 16th days, ip | LVV) and function indexes | ||||||

| (stroke volume, EF and FS) | |||||||

| Wachtman et al (73) | 30/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, iv | Once a week for | FS | Values provided | |

| rats/female | a total of 6 doses | in the manuscript | |||||

| Zhang et al (74) | 40/Wistar outbred rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Three times per week | The LV end-systolic diameter | Values provided | |

| (brand name Adriamycin) | (total 15 mg/kg) | for one week. After a | (LVSD), the LV end-diastolic | in the manuscript | |||

| two-week interval, | diameter (LVDD), the LV | ||||||

| administration for | end-systolic volume (LVSV) | ||||||

| another week. These | and the LV end-diastolic | ||||||

| steps were conducted | volume (LVDV) + The LV | ||||||

| 6 times | ejection fraction (LVEF) | ||||||

| and the LV shortening | |||||||

| fraction (LVFS) | |||||||

| Chen et al (75) | 39/ Wister rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Six times for 2 weeks | LV end diastolic diameter | Values provided | |

| (LVEDd), LV end systolic | in the manuscript | ||||||

| diameter (LVESd) and ejection | |||||||

| fraction (EF) + FS + LV | |||||||

| systolic pressure (LVSP), LV | |||||||

| end diastolic pressure (LVEDP), | |||||||

| LV maximum dP/dt and | |||||||

| LV minimum dP/dt | |||||||

| Ha et al (76) | 60/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg, iv | Once a week for 2, 4, | LV performance | Values calculated | |

| (brand name Adriamycin) | 6 or 8 weeks, | LV dimensions (end-diastolic | manually by the | ||||

| consecutively | and end-systolic diameter) | authors of this | |||||

| + EF | review | ||||||

| Emanuelo et al (77) | 40/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Every second day | LV systolic pressure (LVSP) | Values calculated | |

| rats/male | (total 15 mg/kg) | for a period of | Diastolic and systolic | manually by the | |||

| 2 weeks | LV wall thickness, LVEDD, | authors of this | |||||

| and LVESD were measured | review | ||||||

| + percent LV FS | |||||||

| Lim (78) | 52/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Six times | LVES dimensions, LVED | Values provided | |

| rats/male | over 2 weeks | dimensions, LVFS | in the manuscript | ||||

| Hydock et al (79) | 147/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 10 mg/kg, ip | Acute administration | SWT during systole (SWs) | Values calculated | |

| rats/male | (bolus injection) | and diastole (SWd), PWT and | manually by the | ||||

| PWT during diastole (PWd), | authors of this | ||||||

| LVEDd, LVESd, FS | review | ||||||

| Xiang et al (80) | 37/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Once a week | LVEDd and LVESd + | Values provided | |

| rats/male | for 6 weeks | LV FS (%) | in the manuscript | ||||

| Kenk et al (81) | 94/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 6 injections | LV internal diameter | Values provided | |

| rats/male | (brand name Adriamycin) | (total 15 mg/kg) | over 2 weeks | (LV diastolic and systolic | in the manuscript | ||

| dimensions; LVDD and | |||||||

| LVSD), LV posterior | |||||||

| wall (LVPW), and intra- | |||||||

| ventricular septum (IVS) | |||||||

| thickness at end-diastole | |||||||

| and peak systole. | |||||||

| →LV volume in diastole | |||||||

| and systole (LVDV, LVSV), | |||||||

| stroke volume (SV), | |||||||

| EF, FS, and LV mass | |||||||

| Katona et al (82) | 23/Adult Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Three times a week | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| (brand name Adriamycin) | for 2 weeks | LVDDd and LVSDd, | in the manuscript | ||||

| FS, LAD, AOD | |||||||

| Hydock et al (83) | 49/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 1.5 mg/kg i.p of | Once a day for | Septal wall thickness at systole | Values provided | |

| rats/female | (cumulative 15 mg/kg) | 10 consecutive days | (SWs) and diastole (SWd), | in the manuscript | |||

| posterior wall thickness at | |||||||

| systole (PWs) and diastole | |||||||

| (PWd), LVDs and LVDd, | |||||||

| and FS | |||||||

| Hou et al (84) | 40/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 6 times for 2 weeks | LV dimensions | Values provided | |

| (brand name Adriamycin) | [end-diastolic diameter | in the manuscript | |||||

| (LVDd) and end systolic | |||||||

| diameter (LVDs)] + % FS | |||||||

| of the LV | |||||||

| Hydock et al (85) | 74/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 1 mg/kg, ip | Once a day for | Septal wall thickness | Values provided | |

| rats/male | (total 10 mg/kg) | 10 consecutive days | at systole (SWs) and diastole | in the manuscript | |||

| (SWd), posterior wall thickness | |||||||

| at systole (PWs) and diastole | |||||||

| (PWd), LVDs and LVDd. | |||||||

| + FS, LV mass and relative | |||||||

| wall thickness (RWT). | |||||||

| Koh et al (86) | 33/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg, iv | Once a week | LV dimensions (the LVDd, | Values provided | |

| (brand name Adriamycin) | for 8 weeks | LVDs, the intraventricular | in the manuscript | ||||

| septal thickness, and the LV | |||||||

| posterior wall thickness) + | |||||||

| % FS of LV atrial natriuretic | |||||||

| peptide; brain natriuretic peptide | |||||||

| Carresi et al (87) | 40/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 6 times for 2 weeks | LVESd; LVEDd; IVSs; | Values provided | |

| IVSd, LVPWs and LVPWd; | in the manuscript | ||||||

| EF; FS | |||||||

| Ma et al (88) | 190/Wistar rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 6 times for 2 weeks | LVEDD) and LVESD | Values provided | |

| + FS + EF | in the manuscript | ||||||

| Zhang et al (89) | 26/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 4 mg/kg, ip | Twice per week | Diastolic interventricular | Values calculated | |

| rats/male | (cumulative dose | for 2 weeks | septum thickness (IVSTd), | manually by the | |||

| 16 mg/kg) | systolic interventricular septum | authors of this | |||||

| thickness (IVSTs), + EF + FS | review | ||||||

| Sun et al (90) | 32/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 20 mg/kg, ip | Acute administration | (LVEF) from EDV and ESV, | Values provided | |

| rats/male | 5.0 mg/kg, iv | (single dose) | + EDV and ESV | in the manuscript | |||

| + LVFS | |||||||

| Zhu et al (91) | 50/Adult Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg/week | 6 weeks | Ejection fraction | Values provided | |

| rats/male | in the manuscript | ||||||

| Croteau et al (92) | 12/ Fisher rats/male | Doxorubicin | 2 mg/kg, iv | Once a week | Left ventricular function | Values provided | |

| for 6 weeks | Left ventricle ejection fraction | in the manuscript | |||||

| Ikegami et al (93) | 14/Sprague-Dawley/NM | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | 3 times a week | LVDd and LVFS + FS | Values provided | |

| for 2 to 6 weeks | in the manuscript | ||||||

| Hiona et al (94) | 24/Sprague Dawley | Doxorubicin | Cumulative dose of | Once a week | LVFS | Values provided | |

| rats/female | 25 mg/kg, ip | for 6 weeks | in the manuscript | ||||

| Tang et al (95) | 40/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, ip | Once a day for | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | a total of 6 times | LVEF, LVIDd, LVIDs, | in the manuscript | ||||

| LVPWd, LVPWs, left ventricle | |||||||

| % EF, and left ventricle % FS | |||||||

| Migrino et al (96) | 31/Sprague Dawley | Doxorubicin | 2.5 mg/kg, iv | Once a week | FS monitored | Values provided | |

| rats/male | for 10 or 12 weeks | in the manuscript | |||||

| Liu et al (97) | 24/Sprague-Dawley | Doxorubicin | Each dose consisted of | At 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, | Parameters monitored: | Values provided | |

| rats/male | (brand name Adriamycin) | 1, 1, 2, 2, 3 and 3 mg/kg, | 9th and 11th day, | interventricular septum | in the manuscript | ||

| ip (cumulative dose | respectively | thickness of systolic, IVSd, | |||||

| 12 mg/kg) | LVIDd, LVISd, LVPW, | ||||||

| LVPWd, EF, FS | |||||||

| Liu et al (98) | 120/Sprague Dawley | Doxorubicin | 3.3 mg/kg, iv | Once a week | Values provided | ||

| rats/NM | for 4 weeks | in the manuscript |

LV, left ventricular; LVEF, LV ejection fraction; LVFS: LV fractional shortening; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; PWT, posterior wall thickness; AWT, anterior wall thickness; SWT, septal wall thickness; BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; LVSP, LV systolic pressure; LVDP, LV diastolic pressure; LVEDd, LV end-diastolic diameter; LVESd, LV end-systolic diameter; LVEDV, LV end-diastolic volume; LVIDd, LV internal diastolic diameter LVISd, LV internal systolic diameter; LVPWs, LV systolic wall thickness; LVPWd, LV diastolic wall thickness; IVSd, intraventricular septum in diastole; LAD, left atrial diameter; AOD, aortic diameter; ip, intraperitoneally; iv, intravenously; NM, not mentioned; SD, Sprague-Dawley.

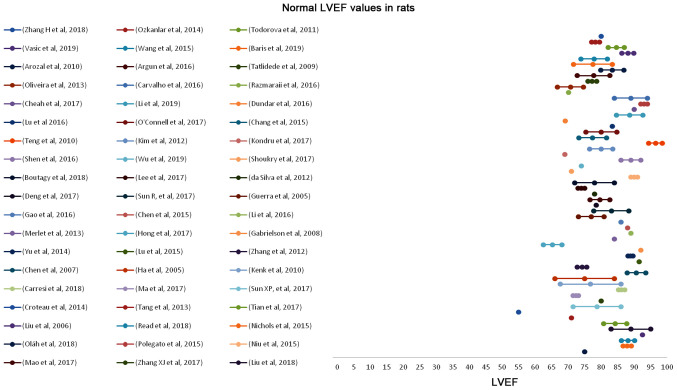

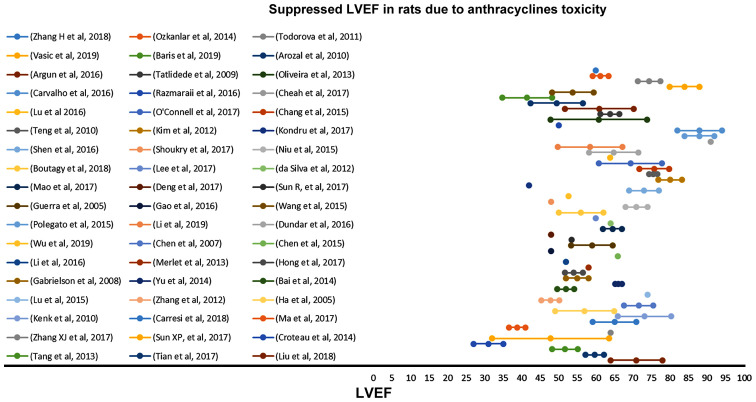

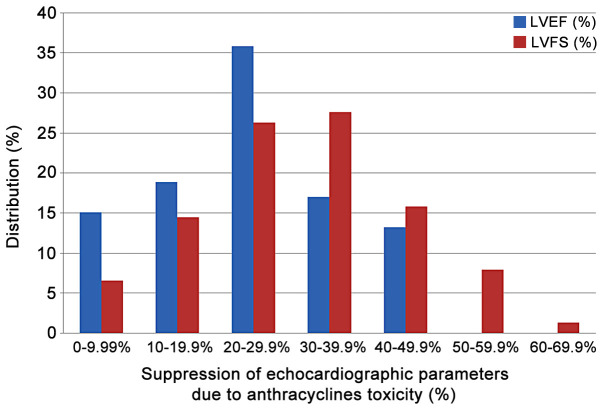

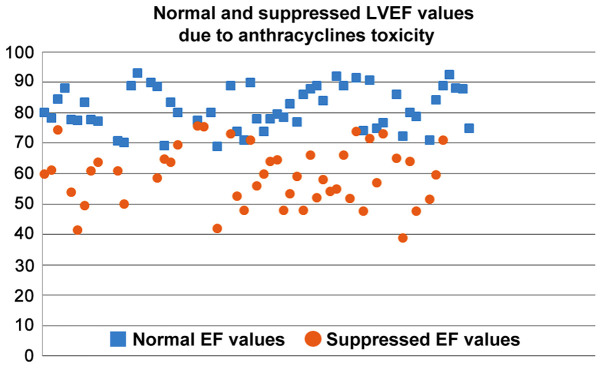

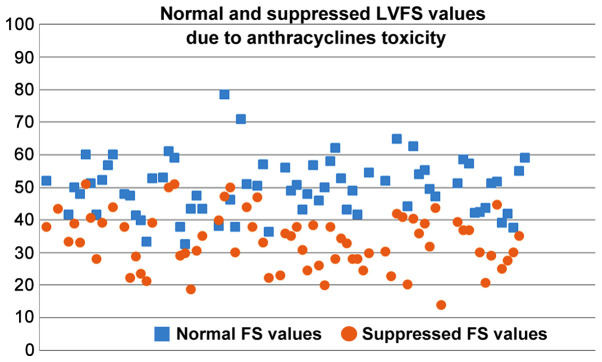

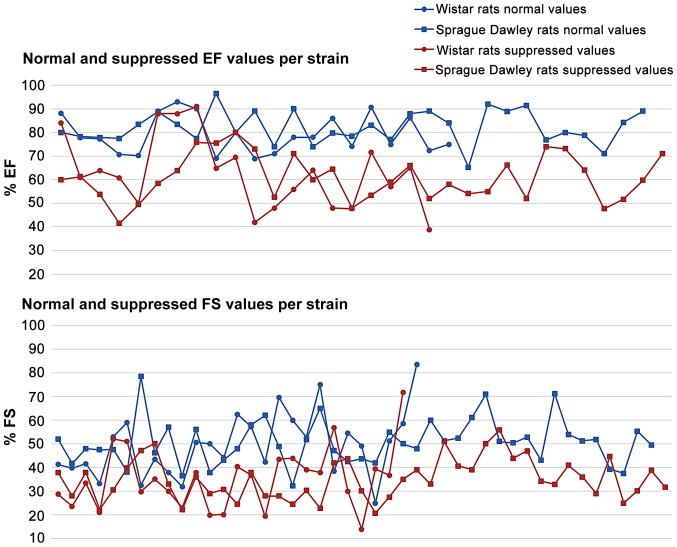

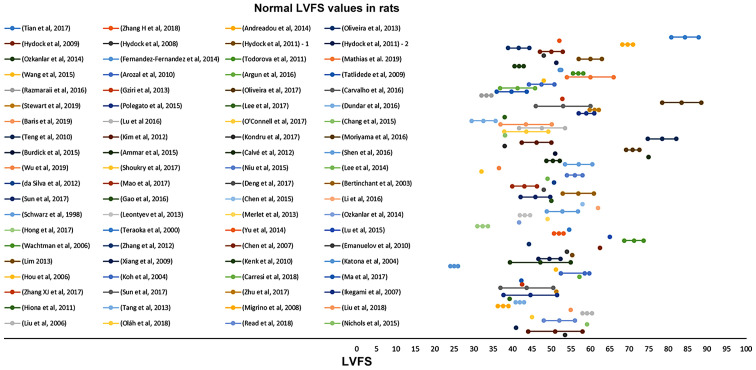

In Figs. 2–5, the normal and suppressed values of the two main echocardiographic indices discussed, %EF and %FS, respectively, are presented. Reported baseline (normal) %EF values in rats vary (55-96.5%). In 78.2% of the studies reviewed, normal values range from 70 to 90%. High %EF values (>90%) are reported in 14% of the studies. In contrast, normal %FS values present even higher variability (25-84.2%). The majority (66.7%) of the values, though, are reported to be within the range of 40 and 60%.

Figure 2.

Normal (baseline) LVEF values in rats before anthracycline administration as reported in 57 relevant studies reviewed in the present report. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

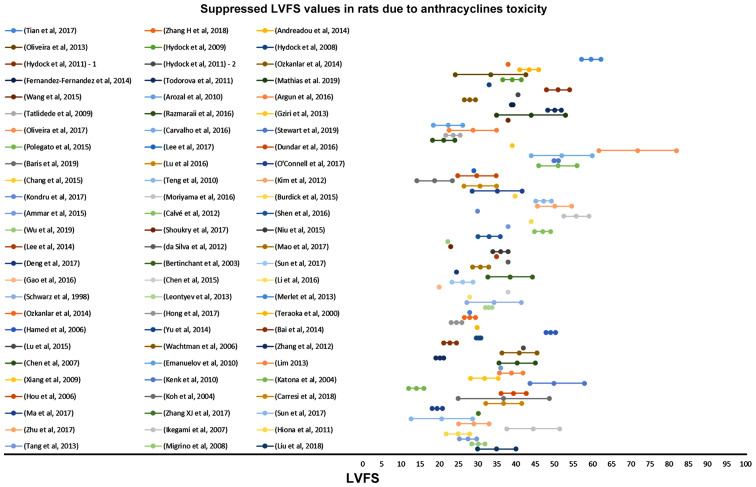

Figure 5.

Suppressed LVFS values in rats due to anthracycline toxicity as reported in 78 relevant studies reviewed in the present report. LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening.

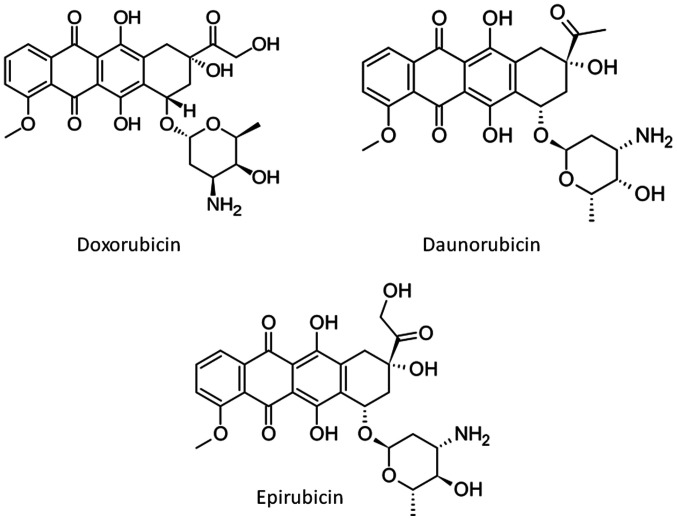

Exposure to anthracyclines suppresses both echocardiographic indices. In the 86 studies reviewed in the present report, Doxorubicin is almost universally used to induce cardiotoxicity, along with Daunorubicin and Epirubicin in two studies (Table I). The structures of the three anthracyclines used are presented in Fig. 6. Anthracyclines were administered with order of appearance either via intraperitoneal injection, intravenous injection or orally with the feed. The doses were administered once, twice, three times per week. The duration of the dose administration spans from one week to ten weeks. In most of the experiments, the benchmark for terminating the administration was the proof of cardiac toxicity. The echocardiography values suggest that there is no specific dose regime threshold which indicates the establishment of the effect, but it is specific to each experiment and probably dependent on other factors such as age and general condition of the animals.

Figure 6.

Chemical structures of the three anthracyclines used to induce cardiotoxicity in the studies reviewed in the present report.

The suppressed %EF values reported from rats after anthracyclines administration vary from 31 to 91% (Fig. 4). EF values 50–80% are reported in 72.3% of the studies reviewed. Suppression of the %EF due to anthracycline administration varies from 10 to 40% compared to the normal values in more than two thirds of the studies reviewed (71.7%) (Fig. 7). On the other hand, suppressed %FS values ranging from 14 to 71.8%, present a more narrow distribution (%FS values 20–50% in 84.6% of the studies). As shown in Fig. 7, a more equal distribution of the %FS suppression due to anthracycline toxicity is observed with approximately one fourth of the studies reporting 20–30% and 30–40% suppression, respectively. It is evident from Figs 8 and 9 that normal and suppressed %EF and %FS values separate sufficiently well. The rat strain does not seem to influence either the normal or the suppressed %EF and %FS values (Fig. 10).

Figure 4.

Suppressed LVEF values in rats due to anthracycline toxicity as reported in 54 relevant studies reviewed in the present report. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Figure 7.

Percentiles distribution of % suppression of LVEF and LVFS due to anthracycline toxicity as mentioned in the studies reviewed in the present report. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening.

Figure 8.

Scatter plot of normal (baseline) and suppressed LVEF values in rats due to anthracycline toxicity as reported the studies reviewed in the present report. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Figure 9.

Scatter plot of normal (baseline) and suppressed LVFS values in rats due to anthracycline toxicity as reported in the studies reviewed in the present report. LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening.

Figure 10.

Normal and suppressed LVEF and LVFS values for the two main rat strains used in the studies reviewed in the present report. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening.

Only 11 studies used an acute administration scheme, with 3–20 mg/kg bw anthracycline single injection either intravenously or intraperitoneally. Most of the studies used a prolonged administration period, from 2 weeks (33 studies) up to 10 weeks, and cumulative doses ranging from 1 to 20 mg/kg bw. All dosage schemes were carefully selected to induce cardiotoxicity and did not seem to affect the suppression of %EF and %FS monitored.

Discussion

Myocardial contractility suppression due to anthracycline administration is of increasing interest and represents a major challenge in the clinical setting. At the same time in a preclinical stage it serves as a model for the assessment of both new chemotherapeutic and cardioprotective agents to be introduced in clinical practice. The myocardial toxicity of anthracyclines is known to be affected by sex and age, along with a number of cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities (99). It is found that anthracycline related congestive heart failure reaches 10% of patients older than 65 years at usual doses (100). While in early studies it was thought that EF cannot accurately predict congestive heart failure attributed to doxorubicin (100), current perspective is that anthracycline-related cardiotoxicity is manifested by a progressive continuous decline in LVEF (1) and identifying subclinical myocardial dysfunction related to anthracycline treatment has great therapeutic implications (2).

Preclinical animal studies are essential in cancer chemotherapy research along with the evaluation of the cardiotoxic propensity of the chemotherapeutic agents. The current recommendations for prevention of cardiac events from cancer chemotherapies are largely based on recommendations. The American Society of Clinical Oncology, for example, recommends active screening and prevention of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, such as tobacco use, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, alcohol use, obesity and physical inactivity (101). A well characterized animal model for defining cardiotoxicity due to chemotherapy and the treatment thereof is of great importance for clinical practice, as it will enable physicians to base their decisions not only on epidemiology but also on observations developed using concrete data from animal studies.

In the present review, the range of the main echocardiographic indices, namely EF and FS, used in describing anthracycline cardiotoxicity in rats was summarized along with the normal values of the said indices presented in the respective studies. In the graphic representation, it seems that normal and suppressed values due to anthracyclines administration for the two echocardiographic indices are well separated. This provides the first evidence for the possibility of setting a cut-off point for defining anthracycline cardiotoxicity in rats with an in-depth future meta-analysis.

In the current study a wide range of EF and FS decline due to anthracycline administration was observed. However, the trends of the said decline are easily identified, especially for FS values, thus rendering the establishment of minimum cut off values of decline feasible. The question remains, as it has also been identified for humans, whether the absolute suppressed values of EF and FS, combined or separately, or the % suppression caused by anthracyclines should be used to describe cardiotoxicity, and which of the two approaches could be more effective in prevention. In our study, it seems that setting a range for % suppression of EF and FS could be more efficient in identifying early cardiotoxicity by counteracting the intra-individual variation of the absolute values.

In the current in depth review analysis, we did not identify differences between rat strains in terms of suppressed EF and FS values due to anthracycline administration. This is an interesting finding as it seems that the usual strains used in rat studies are equally prone to the cardiotoxic anthracycline potential. In animal models of genetically programmed hypertension and heart failure, it is found that doxorubicin administration did not lead to lower myocardial contractility compared to non-genetically modified strains (102). In addition, in the current systematic review, acute and chronic anthracyclines cardiotoxicity models were found equally potent in inducing cardiotoxicity based on evaluated echocardiographic indices.

Currently, when assessing chemicals toxicity, cardiac effects if monitored and detected in animal studies, mainly on the tissue level, are considered by the authorities, but cardiotoxicity, as such, is not described as a separate hazard class of chemical substances through the available regulations, both at a European level and world-wide. Therefore, chemicals other than pharmaceutical agents are recognised to be cardiotoxic after having exerted such deleterious effects on humans, based on epidemiological studies. In a previous review of our research team, the cardiac pathology and function impairment due to exposure to pesticides revealed that several cardiovascular complications have been reported in animal models including electrocardiogram abnormalities, myocardial infarction, impaired systolic and diastolic performance and histopathological findings, such as haemorrhage, vacuolization, signs of apoptosis and degeneration (103). In addition, there is evidence that short and/or long-term exposure to anabolic androgenic steroids is linked to a variety of cardiovascular complications which could be identified by using echocardiography or biochemical markers (10,104,105). The published data suggest clearly that there is a need to establish regulatory criteria for assessing cardiotoxicity as an inherent property of a chemical substance well in advance, and characterize the risk of exposure to such chemicals through a well-developed regulatory network based on animal models, as is the case for other human health hazard classes, such as carcinogenicity. Regulatory established criteria will enable international organizations to early identify cardiotoxic effects and classify chemicals in order to avoid long-term cardiovascular complications. Specific classification criteria should be developed based on anatomical, histopathological, echocardiographic and biochemical criteria in animals developed in a way that could exclude confounding factors in the development of the observed cardiotoxicity. The results of the present study are promising in identifying echocardiographic criteria in rats for the establishment of cardiotoxicity. Further studies and meta-analyses are needed in order to evaluate other species, commonly used in research, and explore the possibility of early recognizing the onset of cardiotoxicity, possibly through monitoring of biochemical markers based on understanding of the mode of action.

Figure 3.

Normal (baseline) LVFS values in rats before anthracycline administration as reported in 80 relevant studies reviewed in the present report. LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Glossary

Abbreviations

- LV

left ventricular

- LVEF

LV ejection fraction

- LVFS

LV fractional shortening

- BNP

brain natriuretic peptide

- PWT

posterior wall thickness

- AWT

anterior wall thickness

- SWT

septal wall thickness

- BP

blood pressure

- HR

heart rate

- LVSP

LV systolic pressure

- LVDP

LV diastolic pressure

- LVEDd

LV end-diastolic diameter

- LVESd

LV end-systolic diameter

- LVEDV

LV end-diastolic volume

- LVIDd

LV internal diastolic diameter

- LVISd

LV internal systolic diameter

- LVPWs

LV systolic wall thickness

- LVPWd

LV diastolic wall thickness

- IVSd

intraventricular septum in diastole

- LAD

left atrial diameter

- AOD

aortic diameter

- ACEIs

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARBs

angiotensin II receptor blockers

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Authors' contributions

All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript. This report is part of the PhD Thesis of NG supervised by DS, KTo and DK and performed in the University of Thessaly. NG: organization and performing of the research, collecting data, writing of the research article. KT, CT: conceptualization of the project, setting criteria for the research, verification of the results, reviewing the manuscript, the statistics and the reference list, overall project management. RR, HN, GENK, JLCMD: data extraction, evaluation of the results, statistical analysis. DAS, DS, KTo, DK, CT: overall project overview, data assessment, evaluation of the results, evaluation of the applicability of the findings, reviewing and writing of the research article and plan assessment.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Patients consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

DAS is the Editor-in-Chief for the journal, but had no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this article. The positions and opinions presented in this article are those of the authors (NG, GENK, JLCMD) alone and are not intended to represent the views or any official position or scientific works of the European Agencies EFSA and ECHA. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, Habib G, Lenihan DJ, Lip GYH, Lyon AR, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2768–2801. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plana JC, Galderisi M, Barac A, Ewer MS, Ky B, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Ganame J, Sebag IA, Agler DA, Badano LP, et al. Expert consensus for multimodality imaging evaluation of adult patients during and after cancer therapy: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:911–939. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardo Sanz A, Zamorano JL. ‘Cardiotoxicity’: time to define new targets? Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1730–1732. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park CJ, Branch ME, Vasu S, Melendez GC. The role of cardiac MRI in animal models of cardiotoxicity: hopes and challenges. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2020 Apr 4; doi: 10.1007/s12265-020-09981-8. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sobczuk P, Czerwinska M, Kleibert M, Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska A. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system-from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Heart Fail Rev. 2020 May 30; doi: 10.1007/s10741-020-09977-1. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashemzaei M, Karami SP, Delaramifar A, Sheidary A, Tabrizian K, Rezaee R, Shahsavand S, Arsene AL, Tsatsakis AM, Mohammad S. Anticancer effects of co-administration of daunorubicin and resveratrol in MOLT-4, U266 B1 and RAJI cell lines. Farmacia. 2016;64:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iranshahi M, Barthomeuf C, Bayet-Robert M, Chollet P, Davoodi D, Piacente S, Rezaee R, Sahebkar A. Drimane-type sesquiterpene coumarins from ferula gummosa fruits enhance doxorubicin uptake in doxorubicin-resistant human breast cancer cell line. J Tradit Complement Med. 2014;4:118–125. doi: 10.4103/2225-4110.126181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarz ER, Pollick C, Dow J, Patterson M, Birnbaum Y, Kloner RA. A small animal model of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and its evaluation by transthoracic echocardiography. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;39:216–223. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robert J. Preclinical assessment of anthracycline cardiotoxicity in laboratory animals: Predictiveness and pitfalls. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2007;23:27–37. doi: 10.1007/s10565-006-0142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germanakis I, Tsarouhas K, Fragkiadaki P, Tsitsimpikou C, Goutzourelas N, Champsas MC, Stagos D, Rentoukas E, Tsatsakis AM. Oxidative stress and myocardial dysfunction in young rabbits after short term anabolic steroids administration. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;61:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA, PRISMA-P Group Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zacchigna S, Paldino A, Falcao-Pires I, Daskalopoulos EP, Dal Ferro M, Vodret S, Lesizza P, Cannatà A, Daniela Miranda-Silva D, et al. Toward standardization of echocardiography for the evaluation of left ventricular function in adult rodents: a position paper of the ESC Working Group on Myocardial Function. Cardiovasc Res. 2020 May 4; doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa110. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Rigel DF. Echocardiographic examination in rats and mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;573:139–155. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-247-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Lu X, Liu Z, Du K. Rosuvastatin reduces the pro-inflammatory effects of adriamycin on the expression of HMGB1 and RAGE in rats. Int J Mol Med. 2018;42:3415–3423. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian XQ, Ni XW, Xu HL, Zheng L, ZhuGe DL, Chen B, Lu CT, Yuan JJ, Zhao YZ. Prevention of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy using targeted MaFGF mediated by nanoparticles combined with ultrasound-targeted MB destruction. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:7103–7119. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S145799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andreadou I, Mikros E, Ioannidis K, Sigala F, Naka K, Kostidis S, Farmakis D, Tenta R, Kavantzas N, Bibli SI, et al. Oleuropein prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy interfering with signaling molecules and cardiomyocyte metabolism. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;69:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveira MS, Melo MB, Carvalho JL, Melo IM, Lavor MSI, Gomes DA, de Goes AM, Melo MM. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and cardiac function improvement after stem cell therapy diagnosed by strain echocardiography. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2013;5:52–57. doi: 10.4172/1948-5956.1000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hydock DS, Lien CY, Hayward R. Anandamide preserves cardiac function and geometry in an acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity rat model. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2009;14:59–67. doi: 10.1177/1074248408329449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez-Fernandez A, Carvajal DA, Lei T, McGoron AJ. Chemotherapy-induced changes in cardiac capillary permeability measured by fluorescent multiple indicator dilution. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:2405–2415. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1110-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Todorova VK, Kaufmann Y, Klimberg VS. Increased efficacy and reduced cardiotoxicity of metronomic treatment with cyclophosphamide in rat breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:215–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasić M, Lončar-Turukalo T, Tasić T, Matić M, Glumac S, Bajić D, Popović B, Japundžić-Žigon N. Cardiovascular variability and β-ARs gene expression at two stages of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019;362:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathias LMBS, Alegre PHC, Dos Santos IOF, Bachiega T, Figueiredo AM, Chiuso-Minicucci F, Fernandes AA, Bazan SGZ, Minicucci MF, Azevedo PS, et al. Euterpe oleracea Mart. (Açai) supplementation attenuates acute doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2019;53:388–399. doi: 10.33594/000000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Chen L, Wang T, Jiang X, Zhang H, Li P, Lv B, Gao X. Ginsenoside Rg3 antagonizes adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity by improving endothelial dysfunction from oxidative stress via upregulating the Nrf2-ARE pathway through the activation of akt. Phytomedicine. 2015;22:875–884. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arozal W, Watanabe K, Veeraveedu PT, Thandavarayan RA, Harima M, Sukumaran V, Suzuki K, Kodama M, Aizawa Y. Effect of telmisartan in limiting the cardiotoxic effect of daunorubicin in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;62:1776–1783. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Argun M, Üzüm K, Sönmez MF, Özyurt A, Derya K, Çilenk KT, Unalmış S, Pamukcu Ö, Baykan A, Narin F, et al. Cardioprotective effect of metformin against doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in rats. Anatol J Cardiol. 2016;16:234–241. doi: 10.5152/akd.2015.6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tatlidede E, Sehirli O, Velioğlu-Oğünc A, Cetinel S, Yeğen BC, Yarat A, Süleymanoğlu S, Sener G. Resveratrol treatment protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by alleviating oxidative damage. Free Radic Res. 2009;43:195–205. doi: 10.1080/10715760802673008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Razmaraii N, Babaei H, Mohajjel Nayebi A, Assadnassab G, Ashrafi Helan J, Azarmi Y. Crocin treatment prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Life Sci. 2016;157:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gziri MM, Pokreisz P, De Vos R, Verbeken E, Debiève F, Mertens L, Janssens SP, Amant F. Fetal rat hearts do not display acute cardiotoxicity in response to maternal Doxorubicin treatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346:362–369. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.205419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oliveira LF, O'Connell JL, Carvalho EE, Pulici ECC, Romano MMD, Maciel BC, Simões MV. Comparison between radionuclide ventriculography and echocardiography for quantification of left ventricular systolic function in rats exposed to doxorubicin. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2017;108:12–20. doi: 10.5935/abc.20160194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carvalho PB, Gonçalves AF, Alegre PH, Azevedo PS, Roscani MG, Bergamasco CM, Modesto PN, Fernandes AA, Minicucci MF, Paiva SA, et al. Pamidronate attenuates oxidative stress and energetic metabolism changes but worsens functional outcomes in acute doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;40:431–442. doi: 10.1159/000452558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart LK, Smoak P, Hydock DS, Hayward R, O'Brien K, Lisano JK, Boeneke C, Christensen M, Mathias A. Milk and kefir maintain aspects of health during doxorubicin treatment in rats. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102:1910–1917. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-15576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polegato BF, Minicucci MF, Azevedo PS, Carvalho RF, Chiuso-Minicucci F, Pereira EJ, Paiva SA, Zornoff LA, Okoshi MP, Matsubara BB, et al. Acute doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity is associated with matrix metalloproteinase-2 alterations in rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:1924–1933. doi: 10.1159/000374001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KH, Cho H, Lee S, Woo JS, Cho BH, Kang JH, Jeong YM, Cheng XW, Kim W. Enhanced-autophagy by exenatide mitigates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Int J Cardiol. 2017;232:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheah HY, Šarenac O, Arroyo JJ, Vasić M, Lozić M, Glumac S, Hoe SZ, Hindmarch CCT, Murphy D, Kiew LV, et al. Hemodynamic effects of HPMA copolymer based doxorubicin conjugate: A randomized controlled and comparative spectral study in conscious rats. Nanotoxicology. 2017;11:210–222. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2017.1285071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, Xu G, Wei S, Zhang B, Yao H, Chen Y, Liu W, Wang B, Zhao J, Gao Y. Lingguizhugan decoction attenuates doxorubicin-induced heart failure in rats by improving TT-SR microstructural remodeling. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19:360. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2771-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dundar HA, Kiray M, Kir M, Kolatan E, Bagriyanik A, Altun Z, Aktas S, Ellidokuz H, Yilmaz O, Mutafoglu K, et al. Protective effect of acetyl-L-carnitine against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in wistar albino rats. Arch Med Res. 2016;47:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barış VO, Gedikli E, Yersal N, Müftüoğlu S, Erdem A. Protective effect of taurine against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats: Echocardiographical and histological findings. Amino Acids. 2019;51:1649–1655. doi: 10.1007/s00726-019-02801-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu PP, Ma J, Liang XP, Guo CX, Yang YK, Yang KQ, Shen QM, Ma LH, Zhou XL. Xinfuli improves cardiac function, histopathological changes and attenuate cardiomyocyte apoptosis in rats with doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2016;13:968–972. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Connell JL, Romano MM, Campos Pulici EC, Carvalho EEV, de Souza FR, Tanaka DM, Maciel BC, Salgado HC, Fazan-Júnior R, Rossi MA, et al. Short-term and long-term models of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in rats: A comparison of functional and histopathological changes. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2017;69:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang SA, Lim BK, Lee YJ, Hong MK, Choi JO, Jeon ES. A novel angiotensin type I receptor antagonist, Fimasartan, prevents Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:559–568. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.5.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teng LL, Shao L, Zhao YT, Yu X, Zhang DF, Zhang H. The beneficial effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on doxorubicin-induced chronic heart failure in rats. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:940–948. doi: 10.1177/147323001003800320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim YH, Kim M, Park SM, Kim SH, Lim SY, Ahn JC, Song WH, Shim WJ. Discordant impairment of multidirectional myocardial deformation in rats with Doxorubicin induced cardiomyopathy. Echocardiography. 2012;29:720–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2012.01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kondru SK, Potnuri AG, Allakonda L, Konduri P. Histamine 2 receptor antagonism elicits protection against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rodent model. Mol Cell Biochem. 2018;441:77–88. doi: 10.1007/s11010-017-3175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moriyama T, Kemi M, Horie T. Elevated cardiac 3-deoxyglucosone, a highly reactive intermediate in glycation reaction, in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Pathophysiology. 2016;23:237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burdick J, Berridge B, Coatney R. Strain echocardiography combined with pharmacological stress test for early detection of anthracycline induced cardiomyopathy. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2015;73:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ammar HI, Sequiera GL, Nashed MB, Ammar RI, Gabr HM, Elsayed HE, Sareen N, Rub EA, Zickri MB, Dhingra S. Comparison of adipose tissue- and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for alleviating doxorubicin-induced cardiac dysfunction in diabetic rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:148. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0142-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calvé A, Haddad R, Barama SN, Meilleur M, Sebag IA, Chalifour LE. Cardiac response to doxorubicin and dexrazoxane in intact and ovariectomized young female rats at rest and after swim training. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2048–H2057. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01069.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen LJ, Lu S, Zhou YH, Li L, Xing QM, Xu YL. Developing a rat model of dilated cardiomyopathy with improved survival. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2016;17:975–983. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu Z, Zhao X, Miyamoto A, Zhao S, Liu C, Zheng W, Wang H. Effects of steroidal saponins extract from Ophiopogon japonicus root ameliorates doxorubicin-induced chronic heart failure by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Pharm Biol. 2019;57:176–183. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2019.1577467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shoukry HS, Ammar HI, Rashed LA, Zikri MB, Shamaa AA, Abou Elfadl SG, Rub EA, Saravanan S, Dhingra S. Prophylactic supplementation of resveratrol is more effective than its therapeutic use against doxorubicin induced cardiotoxicity. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niu QY, Li ZY, Du GH, Qin XM. (1)H NMR based metabolomic profiling revealed doxorubicin-induced systematic alterations in a rat model. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;118:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boutagy NE, Wu J, Cai Z, Zhang W, Booth CJ, Kyriakides TC, Pfau D, Mulnix T, Liu Z, Miller EJ, et al. In vivo reactive oxygen species detection with a novel positron emission tomography tracer, 18F-DHMT, allows for early detection of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in rodents. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2018;3:378–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee PJ, Rudenko D, Kuliszewski MA, Liao C, Kabir MG, Connelly KA, Leong-Poi H. Survivin gene therapy attenuates left ventricular systolic dysfunction in doxorubicin cardiomyopathy by reducing apoptosis and fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;101:423–433. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.da Silva MG, Mattos E, Camacho-Pereira J, Domitrovic T, Galina A, Costa MW, Kurtenbach E. Cardiac systolic dysfunction in doxorubicin-challenged rats is associated with upregulation of MuRF2 and MuRF3 E3 ligases. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2012;17:101–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mao C, Hou X, Wang B, Chi J, Jiang Y, Zhang C, Li Z. Intramuscular injection of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells improves cardiac function in dilated cardiomyopathy rats. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:18. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0472-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deng B, Wang JX, Hu XX, Duan P, Wang L, Li Y, Zhu QL. Nkx2.5 enhances the efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells transplantation in treatment heart failure in rats. Life Sci. 2017;182:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bertinchant JP, Polge A, Juan JM, Oliva-Lauraire MC, Giuliani I, Marty-Double C, Burdy JY, Fabbro-Peray P, Laprade M, Bali JP, et al. Evaluation of cardiac troponin I and T levels as markers of myocardial damage in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy rats, and their relationship with echocardiographic and histological findings. Clin Chim Acta. 2003;329:39–51. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(03)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun R, Wang J, Zheng Y, Li X, Xie T, Li R, Liu M, Cao Y, Lu L, Zhang Q, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine baoxin decoction improves cardiac fibrosis of rats with dilated cardiomyopathy. Exp Ther Med. 2017;13:1900–1906. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guerra J, De Jesus A, Santiago-Borrero P, Roman-Franco A, Rodríguez E, Crespo MJ. Plasma nitric oxide levels used as an indicator of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Hematol J. 2005;5:584–588. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao Y, Yang H, Fan Y, Li L, Fang J, Yang W. Hydrogen-rich saline attenuates cardiac and hepatic injury in doxorubicin rat model by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:1320365. doi: 10.1155/2016/1320365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Y, Tang Y, Xiang Y, Xie YQ, Huang XH, Zhang YC. Shengmai injection improved doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy by alleviating myocardial endoplasmic reticulum stress and caspase-12 dependent apoptosis. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:952671. doi: 10.1155/2015/952671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li H, Mao Y, Zhang Q, Han Q, Man Z, Zhang J, Wang X, Hu R, Zhang X, Irwin DM, et al. Xinmailong mitigated epirubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via inhibiting autophagy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;192:459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leontyev S, Schlegel F, Spath C, Schmiedel R, Nichtitz M, Boldt A, Rübsamen R, Salameh A, Kostelka M, Mohr FW, et al. Transplantation of engineered heart tissue as a biological cardiac assist device for treatment of dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:23–35. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Merlet N, Piriou N, Rozec B, Grabherr A, Lauzier B, Trochu JN, Gauthier C. Increased beta2-adrenoceptors in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in rat. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ozkanlar Y, Aktas MS, Turkeli M, Erturk N, Oruc E, Ozkanlar S, Kirbas A, Erdemci B, Aksakal E. Effects of ramipril and darbepoetin on electromechanical activity of the heart in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173:519–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hong YM, Lee H, Cho MS, Kim KC. Apoptosis and remodeling in adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy rat model. Korean J Pediatr. 2017;60:365–372. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2017.60.11.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Teraoka K, Hirano M, Yamaguchi K, Yamashina A. Progressive cardiac dysfunction in adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy rats. Eur J Heart Fail. 2000;2:373–378. doi: 10.1016/S1388-9842(00)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hamed S, Barshack I, Luboshits G, Wexler D, Deutsch V, Keren G, George J. Erythropoietin improves myocardial performance in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1876–1883. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gabrielson KL, Mok GS, Nimmagadda S, Bedja D, Pin S, Tsao A, Wang Y, Sooryakumar D, Yu SJ, Pomper MG, et al. Detection of dose response in chronic doxorubicin-mediated cell death with cardiac technetium 99m annexin V single-photon emission computed tomography. Mol Imaging. 2008;7:132–138. doi: 10.2310/7290.2008.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu Q, Li Q, Na R, Li X, Liu B, Meng L, Liutong H, Fang W, Zhu N, Zheng X. Impact of repeated intravenous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells infusion on myocardial collagen network remodeling in a rat model of doxorubicin-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;387:279–285. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1894-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bai J, Gu R, Wang B, Zhang N, Kang L, Xu B. Overexpression of integrin-linked kinase improves cardiac function in a rat model of doxorubicin-induced chronic heart failure. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2014;42:225–229. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lu XL, Tong YF, Liu Y, Xu YL, Yang H, Zhang GY, Li XH, Zhang HG. Gαq protein carboxyl terminus imitation polypeptide GCIP-27 improves cardiac function in chronic heart failure rats. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wachtman LM, Browning MD, Bedja D, Pin S, Gabrielson KL. Validation of the use of long-term indwelling jugular catheters in a rat model of cardiotoxicity. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2006;45:55–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang J, Zhang L, Wu Q, Liu H, Huang L. Recombinant human brain natriuretic peptide therapy combined with bone mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for treating heart failure in rats. Mol Med Rep. 2013;7:628–632. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen X, Chen Y, Bi Y, Fu N, Shan C, Wang S, Aslam S, Wang PW, Xu J. Preventive cardioprotection of erythropoietin against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21:367–374. doi: 10.1007/s10557-007-6052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ha JW, Kang SM, Pyun WB, Lee JY, Ahn MY, Kang WC, Jeon TJ, Chung N, Lee JD, Cho SH. Serial assessment of myocardial properties using cyclic variation of integrated backscatter in an adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy rat model. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46:73–77. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Emanuelov AK, Shainberg A, Chepurko Y, Kaplan D, Sagie A, Porat E, Arad M, Hochhauser E. Adenosine A3 receptor-mediated cardioprotection against doxorubicin-induced mitochondrial damage. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lim SC. Interrelation between expression of ADAM 10 and MMP 9 and synthesis of peroxynitrite in doxorubicin induced cardiomyopathy. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2013;21:371–380. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hydock DS, Lien CY, Schneider CM, Hayward R. Exercise preconditioning protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiac dysfunction. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:808–817. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318163744a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xiang P, Deng HY, Li K, Huang G-Y, Chen Y, Tu L, Ng PC, Pong NH, Zhao H, Zhang L, et al. Dexrazoxane protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy: Upregulation of Akt and Erk phosphorylation in a rat model. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:343–349. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kenk M, Thackeray JT, Thorn SL, Dhami K, Chow BJ, Ascah KJ, DaSilva JN, Beanlands RS. Alterations of pre- and postsynaptic noradrenergic signaling in a rat model of adriamycin-induced cardiotoxicity. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17:254–263. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Katona M, Boros K, Sántha P, Ferdinandy P, Dux M, Jancsó G. Selective sensory denervation by capsaicin aggravates adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;370:436–443. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0985-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hydock DS, Parry TL, Jensen BT, Lien CY, Schneider CM, Hayward R. Effects of endurance training on combined goserelin acetate and doxorubicin treatment-induced cardiac dysfunction. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68:685–692. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hou XW, Son J, Wang Y, Ru YX, Lian Q, Majiti W, Amazouzi A, Zhou YL, Wang PX, Han ZC. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improves cardiac function in adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy in rats. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2006;20:85–91. doi: 10.1007/s10557-006-7652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hydock DS, Lien CY, Jensen BT, Schneider CM, Hayward R. Exercise preconditioning provides long-term protection against early chronic doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. Integr Cancer Ther. 2011;10:47–57. doi: 10.1177/1534735410392577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Koh E, Nakamura T, Takahashi H. Troponin-T and brain natriuretic peptide as predictors for adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy in rats. Circ J. 2004;68:163–167. doi: 10.1253/circj.68.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carresi C, Musolino V, Gliozzi M, Maiuolo J, Mollace R, Nucera S, Maretta A, Sergi D, Muscoli S, Gratteri S, et al. Anti-oxidant effect of bergamot polyphenolic fraction counteracts doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy: Role of autophagy and c-kitposCD45negCD31neg cardiac stem cell activation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;119:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ma H, Kong J, Wang YL, Li JL, Hei NH, Cao XR, Yang JJ, Yan WJ, Liang WJ, Dai HY, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 overexpression protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy by multiple mechanisms in rats. Oncotarget. 2017;8:24548–24563. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang XJ, Cao XQ, Zhang CS, Zhao Z. 17β-estradiol protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in male Sprague-Dawley rats by regulating NADPH oxidase and apoptosis genes. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:2695–2702. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sun XP, Wan LL, Yang QJ, Huo Y, Han YL, Guo C. Scutellarin protects against doxorubicin-induced acute cardiotoxicity and regulates its accumulation in the heart. Arch Pharm Res. 2017;40:875–883. doi: 10.1007/s12272-017-0907-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]