Abstract

Background

Glioblastoma (GBM) treatment requires access to complex medical services, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) sought to expand access to health care, including complex oncologic care. Whether the implementation of the ACA was subsequently associated with changes in 1-year survival in GBM is not known.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. We identified patients with the primary diagnosis of GBM between 2008 and 2016. A multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards model was developed using patient and clinical characteristics to determine the main outcome: the 1-year cumulative probability of death by state expansion status.

Results

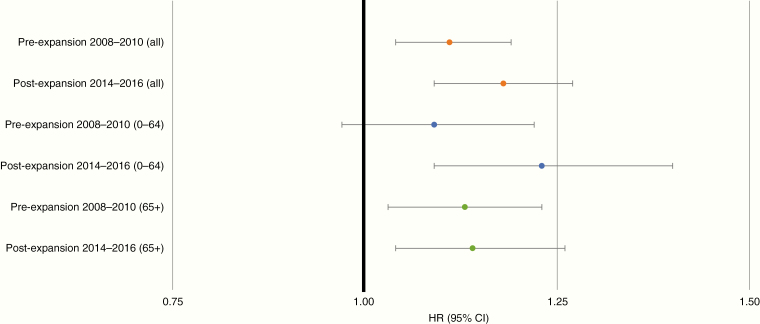

A total of 25 784 patients and 14 355 deaths at 1 year were identified and included in the analysis, 49.7% were older than 65 at diagnosis. Overall 1-year cumulative probability of death for GBM patients in non-expansion versus expansion states did not significantly worsen over the 2 time periods (2008–2010: hazard ratio [HR] 1.11, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.19; 2014–2016: HR 1.18, 95% CI 1.09–1.27). In GBM patients younger than age 65 at diagnosis, there was a nonsignificant trend toward the poorer 1-year cumulative probability of death in non-expansion versus expansion states (2008–2010: HR 1.09, 95% CI 0.97–1.22; 2014–2016: HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.09–1.40).

Conclusions

No differences were found over time in survival for GBM patients in expansion versus non-expansion states. Further study may reveal whether GBM patients diagnosed younger than age 65 in expansion states experienced improvements in 1-year survival.

Keywords: Affordable Care Act, glioblastoma, Medicaid, outcomes research, SEER

Key Points.

Overall, the ACA’s Medicaid expansion had no significant impact on mortality in GBM.

Younger GBM patients may have survived longer in states that expanded Medicaid.

Importance of the Study.

Policymakers spend substantial public resources on health policy reforms and other initiatives with the ultimate goal of improving clinical care and advancing life for patients. The ACA is the most substantial health reform in the United States in decades, and in this study, we use SEER data to investigate changes to 1-year survival related to the timing of the ACA’s implementation. In our study, we found that there were no significant changes in 1-year mortality between expansion and non-expansion states. Further study may reveal whether a trend toward improved 1-year survival among Medicaid-eligible glioblastoma patients younger than age 65 in expansion states versus non-expansion states is significant. Our findings set the stage for more research in this area and suggest that further policy reforms that expand access to healthcare may lead to improved survival for glioblastoma patients.

Glioblastoma (GBM) has a poor prognosis with an estimated 38% 1-year survival rate and 4.6% 5-year survival rate1 due to the aggressive nature of the disease and limited treatment options. The current standard of care includes neurosurgical intervention, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, all requiring health insurance coverage to access complex health delivery systems.2

A key goal of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was to decrease the uninsured rate; under the ACA, states could expand Medicaid eligibility to include low-income individuals. Thirty-seven states including the District of Columbia (DC) expanded Medicaid under the ACA, with the vast majority of these states expanding in early 2014.3 Five states (and DC) implemented heterogeneous early expansion initiatives between 2011 and 2014.4 Many published studies have now demonstrated that Medicaid expansion was associated with increased coverage, service, use, and quality of care for patients across a wide range of diseases.5 In cancer patients specifically, it has been shown that Medicaid expansion led to an increase in overall insurance coverage and subsequent association with survival benefit at the population level.6–8

To our knowledge, there has been no study of the ACA’s impact on outcomes of patients with GBM specifically. One prior study using the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database showed that patients in 2007–2012 with GBM and Medicaid (or no insurance) had a worse survival than those with other insurance.9 But whether the ACA—and in particular Medicaid expansion—led to improved survival for patients with GBM is not known.

In this study, we utilized SEER data to compare the 1-year cumulative probability of death in GBM patients between expansion and non-expansion states in a pre-expansion period (2008–2010) and in the post-expansion period (2014–2016) to evaluate whether policy change led to improved survival.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

We used data from the tumor registries in the 18 areas included in the SEER database (November 2018 submission10) to estimate overall (all causes of death) survival. SEER assembles cancer incidence data from population-based cancer registries across the United States. Analyses included all patients with a primary diagnosis of GBM using ICD-O-3 codes (9440/3: Glioblastoma NOS) between 2008 and 2016. Cases that were determined at autopsy or death certificate only were excluded. For chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment data, the SEER Data-Use Agreement does not allow for comparisons in treatment levels of different groups or comparison of groups by treatment received due to incomplete coding of the data.

Pre-expansion years were defined as 2008–2010, post-expansion was defined as 2014–2016. Given the heterogeneity of implementation of the early expansion, diagnoses from 2011 to 2013 are excluded from analyses (n = 8735). States were categorized as expansion versus non-expansion; however, some states with later expansion dates had cases diagnosed during both the expansion and non-expansion periods according to expansion date. States in the expansion period included Alaska (implemented September 1, 2015), California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana (implemented July 1, 2016), Michigan (Detroit; implemented April 1, 2014), New Jersey, New Mexico, Utah (adopted but not implemented), and Washington (Seattle). States in the non-expansion period included Alaska (implemented September 1, 2015), Georgia, Louisiana (implemented July 1, 2016), Michigan (Detroit; implemented April 1, 2014), and Utah (adopted but not implemented). Given that most Americans are granted Medicare benefits at age 65, we planned subgroup analysis for those aged 65 and older and for those younger than age 65.

Study Variables

We right-truncated follow-up time at 1 year, as median survival for adults with GBM is approximately 8 months.1 There were a total of 4777 deaths in 2008–2010 which accounted for 59.7% of included cases. There were a total of 4517 deaths in 2014–2016 which accounted for 49.9% of included cases. Follow-up time for overall survival was computed as the number of months between the date of diagnosis and the earliest of: month of death from any cause, date of last known contact, date 1 year after diagnosis, or December 2016. Thus, 2794 patients diagnosed after January 2016 did not have the full 1 year of follow-up.

Race/ethnicity was defined using the ‘Race and origin recode’ variable as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, Hispanic (all races), and non-Hispanic unknown race. SEER data on race and Hispanic ethnicity were generally based on patients’ medical records.11,12 Information on birthplace and surname was used to code Hispanic ethnicity when a specific designation was lacking.13

Insurance was categorized using the “Insurance Recode (2007+)” variable as uninsured, any Medicaid, insured, insured/no specifics, and insurance status unknown. This status is derived from primary payer at diagnosis and reflects the most extensive status throughout the course of a patient’s diagnosis and treatment. The uninsured group includes those who were recorded as “not insured” or “non-insured/self-pay.” The any Medicaid group includes those who were recorded as “Indian/Public Health Service,” “Medicaid,” “Medicaid—Administered through a Managed Care plan,” and “Medicare with Medicaid eligibility.” The insured group includes those reported as having private insurance (fee-for-service, managed care, HMO, PPO, or TRICARE) and Medicare (administered through a Managed Care Plan, with private supplement, with supplement, NOS, and Military). The “Insured, No Specifics” group includes those with “Medicare/Medicare, NOS” and “Insurance, NOS”.14

The median tumor size for all GBM patients was 45 mm. Therefore, tumor size was classified as ≤45 mm and >45 mm for analyses, consistent with prior research done with GBM patients.9

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models were developed to estimate the all-cause 1-year cumulative probability of death among GBM cases15 by state ACA status. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by examining the correlation between time and scaled Schoenfeld residuals for all covariates. The assumption of proportional hazards was violated for radiation (yes/no) and thus all models included this variable as a stratification factor to allow hazards to vary by radiation status. Models were also adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, tumor size, surgery status, and chemotherapy status. Wald global (and individual term) tests for interaction with time period (2008–2010 and 2014–2016) were computed using cross-product terms in a fully adjusted overall model additionally adjusted for all statistically significant (P < .05) interactions with time period (insurance and chemotherapy status for all ages; none for 0- to 64-year olds; chemotherapy status for age 65 and older). Sequential modeling analysis was performed as follows: (1) without adjusting for any covariates; (2) adjusting for age/sex/race; (3) additionally adjusting for insurance status; (4) additionally adjusting for tumor size; and (5) additionally adjusting for surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of patients diagnosed with GBM in all study states between 2008 and 2016. Among all states and time periods, there is little change in the percentage of male and female patients. With regard to age, in non-expansion states, there is a decrease over time periods in patients aged 40–64 (2008–2010: 47.2%, 2014–2016: 43.5%) and increase in those 65 and older (2008–2010: 46.8%, 2014–2016: 51.0%); there is a similar but less pronounced change in the age in expansion states over these time periods.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Diagnosed With Glioblastoma in Affordable Care Act Expansiona and Non-expansionb States by Period of Diagnosis (2008–2010 and 2014–2016), SEER Regions

| All 2008–2016 | Expansion states | Non-expansion states | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2010 | 2014–2016 | 2008–2010 | 2014–2016 | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age category, years | ||||||||||

| 0–19 | 330 | 1.3% | 63 | 1.0% | 81 | 1.1% | 35 | 1.9% | 22 | 1.3% |

| 20–39 | 1069 | 4.1% | 261 | 4.2% | 295 | 4.0% | 74 | 4.0% | 69 | 4.2% |

| 40–64 | 11 579 | 44.9% | 2816 | 45.7% | 3221 | 43.6% | 867 | 47.2% | 718 | 43.5% |

| 65+ | 12 806 | 49.7% | 3028 | 49.1% | 3797 | 51.4% | 859 | 46.8% | 843 | 51.0% |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 14 895 | 57.8% | 3548 | 57.5% | 4273 | 57.8% | 1057 | 57.6% | 959 | 58.1% |

| Female | 10 889 | 42.2% | 2620 | 42.5% | 3121 | 42.2% | 778 | 42.4% | 693 | 41.9% |

| Race | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 20 283 | 78.7% | 4902 | 79.5% | 5668 | 76.7% | 1492 | 81.3% | 1352 | 81.8% |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1474 | 5.7% | 214 | 3.5% | 289 | 3.9% | 258 | 14.1% | 198 | 12.0% |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 94 | 0.4% | 20 | 0.3% | 29 | 0.4% | 8 | 0.4% | <5 | 0.2% |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander | 1231 | 4.8% | 301 | 4.9% | 453 | 6.1% | 30 | 1.6% | 20 | 1.2% |

| Hispanic (all races) | 2653 | 10.3% | 719 | 11.7% | 941 | 12.7% | 44 | 2.4% | 77 | 4.7% |

| Non-Hispanic unknown race | 49 | 0.2% | 12 | 0.2% | 14 | 0.2% | <5 | 0.2% | <5 | 0.1% |

| Insurance status | ||||||||||

| Uninsured | 803 | 3.1% | 196 | 3.2% | 123 | 1.7% | 88 | 4.8% | 76 | 4.6% |

| Any Medicaid | 2825 | 11.0% | 667 | 10.8% | 921 | 12.5% | 145 | 7.9% | 115 | 7.0% |

| Non-Medicaid insured | 17 447 | 67.7% | 4164 | 67.5% | 5059 | 68.4% | 1223 | 66.6% | 1130 | 68.4% |

| Insured/No specifics | 3970 | 15.4% | 967 | 15.7% | 1095 | 14.8% | 319 | 17.4% | 254 | 15.4% |

| Insurance status unknown | 739 | 2.9% | 174 | 2.8% | 196 | 2.7% | 60 | 3.3% | 77 | 4.7% |

| Tumor size | ||||||||||

| ≤45 mm | 11 315 | 43.9% | 12 675 | 43.4% | 3304 | 44.7% | 753 | 41.0% | 762 | 46.1% |

| >45 mm | 10 348 | 40.1% | 2432 | 39.4% | 3023 | 40.9% | 764 | 41.6% | 646 | 39.1% |

| Unknown | 4121 | 16.0% | 1061 | 17.2% | 1067 | 14.4% | 318 | 17.3% | 244 | 14.8% |

| Surgery | ||||||||||

| No | 6194 | 24.0% | 1659 | 26.9% | 1645 | 22.2% | 450 | 24.5% | 376 | 22.8% |

| Yes | 19 522 | 75.7% | 4490 | 72.8% | 5724 | 77.4% | 1382 | 75.3% | 1273 | 77.1% |

| Unknown | 68 | 0.3% | 19 | 0.3% | 25 | 0.3% | <5 | 0.2% | <5 | 0.2% |

| Radiation | ||||||||||

| No/Unknown | 7513 | 29.1% | 1852 | 30.0% | 2096 | 28.3% | 529 | 28.8% | 497 | 30.1% |

| Yes | 18 271 | 70.9% | 4316 | 70.0% | 5298 | 71.7% | 1306 | 71.2% | 1155 | 69.9% |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||||

| No/Unknown | 8968 | 34.8% | 2188 | 35.5% | 2490 | 33.7% | 684 | 37.3% | 608 | 36.8% |

| Yes | 16 816 | 65.2% | 3980 | 64.5% | 4904 | 66.3% | 1151 | 62.7% | 1044 | 63.2% |

aAlaska (implemented September 1, 2015), California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana (implemented July 1, 2016), Michigan (Detroit; implemented April 1, 2014), New Jersey, New Mexico, Utah (adopted but not implemented), and Washington (Seattle).

bAlaska (implemented September 1, 2015), Georgia, Louisiana (implemented July 1, 2016), Michigan (Detroit; implemented April 1, 2014), and Utah (adopted but not implemented).

In 2008–2010, there was a lower proportion of non-Hispanic black patients with GBM in expansion states compared to non-expansion states (2008–2010: 3.5% vs 14.1%) and a slightly lower proportion of non-Hispanic white (2008–2010: 79.5% vs 81.3%). Patients in expansion states were in higher proportion Hispanic (2008–2010: 11.7% vs 2.4%) and non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander (2008–2010: 4.9% vs 1.6%). Increases were seen in the diagnosed Hispanic population in both expansion states (2008–2010: 11.7%, 2014–2016: 12.7%) and non-expansion states (2008–2010: 2.4%, 2014–2016: 4.7%).

In states which expanded Medicaid, the uninsured rate among GBM patients decreased substantially between the 2 time periods (2008–2010: 3.2%, 2014–2016: 1.7%), whereas in non-expansion states, the uninsured rate declined only slightly (2008–2010: 4.8%, 2014–2016: 4.6%). Likewise, between the 2 time periods, the percentage of GBM patients on Medicaid in expansion states increased (2008–2010: 10.8%, 2014–2016: 12.5%) but actually decreased in non-expansion states (2008–2010: 7.9%, 2014–2016: 7.0%).

There was an increase in patients in expansion states who were reported to have undergone neurosurgery (2008–2010: 72.8%, 2014–2016: 77.4%); in non-expansion states the increase was more modest (2008–2010: 75.3%, 2014–2016: 77.1%).

Table 2 illustrates patient demographics by insurance status over the entire period studied. Patients with Medicaid insurance were younger overall (68.9% are younger than age 65, compared to 49.6% with private or Medicare insurance). A lower proportion of patients with Medicaid were non-Hispanic white (53.8% vs 83.2%), and higher proportions were non-Hispanic black (10.1% vs 4.5%), non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (1.2% vs 0.2%), non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander (9.0% vs 4.2%), and Hispanic (25.5% vs 7.7%). Patients with non-Medicaid insurance had similar age and sex distributions compared to others with GBM but a higher proportion of them were non-Hispanic white (83.2% vs 78.7%).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics by Insurance Status for Patients Diagnosed With Glioblastoma (2008–2016), SEER Regions

| All | Uninsured | Any Medicaid | Non-Medicaid insured | Insured/ No specifics | Insurance status unknown | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age category, years | ||||||||||||

| 0–19 | 330 | 1.3% | <5 | 0.5% | 109 | 3.9% | 176 | 1.0% | 29 | 0.7% | 12 | 1.6% |

| 20–39 | 1069 | 4.1% | 86 | 10.7% | 269 | 9.5% | 596 | 3.4% | 87 | 2.2% | 31 | 4.2% |

| 40–64 | 11 579 | 44.9% | 617 | 76.8% | 1568 | 55.5% | 7890 | 45.2% | 1209 | 30.5% | 295 | 39.9% |

| 65+ | 12 806 | 49.7% | 96 | 12.0% | 879 | 31.1% | 8785 | 50.4% | 2645 | 66.6% | 401 | 54.3% |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 14 895 | 57.8% | 498 | 62.0% | 1607 | 56.9% | 10 180 | 58.3% | 2229 | 56.1% | 381 | 51.6% |

| Female | 10 889 | 42.2% | 305 | 38.0% | 1218 | 43.1% | 7267 | 41.7% | 1741 | 43.9% | 358 | 48.4% |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 20 283 | 78.7% | 486 | 60.5% | 1521 | 53.8% | 14 521 | 83.2% | 3178 | 80.1% | 577 | 78.1% |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1474 | 5.7% | 92 | 11.5% | 286 | 10.1% | 793 | 4.5% | 248 | 6.2% | 55 | 7.4% |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 94 | 0.4% | <5 | 0.1% | 34 | 1.2% | 39 | 0.2% | 16 | 0.4% | <5 | 0.5% |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander | 1231 | 4.8% | 56 | 7.0% | 253 | 9.0% | 728 | 4.2% | 169 | 4.3% | 25 | 3.4% |

| Hispanic (all races) | 2653 | 10.3% | 166 | 20.7% | 721 | 25.5% | 1347 | 7.7% | 353 | 8.9% | 66 | 8.9% |

| Non-Hispanic unknown race | 49 | 0.2% | <5 | 0.2% | 10 | 0.4% | 19 | 0.1% | 6 | 0.2% | 12 | 1.6% |

One-Year Survival

Table 3 includes the results of the multivariable-adjusted 1-year cumulative probability of death examined by state expansion status and expansion time periods. In pre-expansion years, GBM patients in non-expansion states had 11% higher 1-year cumulative probability of death than those in expansion states (hazard ratio [HR] 1.11, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04–1.19). Post-expansion, 1-year cumulative probability of death was 18% higher among those in non-expansion states compared to expansion states, but results were not significantly different between time periods given overlapping confidence intervals (HR 1.18, 95% CI: 1.09–1.27).

Table 3.

Multivariable-Adjusted Hazard Ratios (HRs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) of 1-Year Overall Cumulative Probability of Death for Patients Diagnosed With Glioblastoma in All Included Statesa by Period of Diagnosis (2008–2010 and 2014–2016)

| Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | Interaction P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2010 | 2014–2016 | ||||

| N = 8003 | N = 9046 | ||||

| No. of deaths | HR (95% CI) | No. of deaths | HR (95% CI) | ||

| ACA status | .3628 | ||||

| Expansion states | 1129 | Reference | 950 | Reference | |

| Non-expansion states | 3648 | 1.11 (1.04–1.19) | 3567 | 1.18 (1.09–1.27) | |

| Age category, years | .2324 | ||||

| 0–19 | 44 | Reference | 46 | Reference | |

| 20–39 | 85 | 0.53 (0.37–0.76) | 77 | 0.51 (0.35–0.74) | |

| 40–64 | 1659 | 1.11 (0.82–1.50) | 1440 | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | |

| 65+ | 2989 | 2.16 (1.60–2.91) | 2954 | 1.83 (1.36–2.46) | |

| Sex | .4921 | ||||

| Male | 2699 | Reference | 2581 | Reference | |

| Female | 2078 | 0.97 (0.91–1.02) | 1936 | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) | |

| Race | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 3878 | Reference | 3599 | Reference | .1572 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 282 | 0.93 (0.82–1.06) | 238 | 0.82 (0.71–0.93) | |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 11 | 0.57 (0.31–1.03) | 14 | 1.31 (0.77–2.22) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander | 163 | 0.69 (0.59–0.81) | 192 | 0.80 (0.69–0.92) | |

| Hispanic (all races) | 434 | 0.94 (0.85–1.04) | 469 | 0.91 (0.82–1.00) | |

| Non-Hispanic unknown race | 9 | 0.60 (0.31–1.17) | 5 | 0.45 (0.19–1.09) | |

| Insurance status | .0425 | ||||

| Uninsured | 143 | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 86 | 1.13 (0.91–1.40) | |

| Any Medicaid | 499 | 1.08 (0.98–1.20) | 500 | 1.14 (1.03–1.26) | |

| Non-Medicaid insured | 3127 | Reference | 2999 | Reference | |

| Insured/No specifics | 851 | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 765 | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | |

| Insurance status unknown | 157 | 0.73 (0.61–0.86) | 167 | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | |

| Tumor size at diagnosis | .4645 | ||||

| ≤45 mm | 1929 | Reference | 1947 | Reference | |

| >45 mm | 1977 | 1.23 (1.16–1.31) | 1866 | 1.16 (1.09–1.24) | |

| Unknown | 871 | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 704 | 1.00 (0.92–1.10) | |

Cox regression models stratified by radiation and adjusted for surgery and chemotherapy.

aAlaska (Natives), California, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan (Detroit), New Jersey, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington (Seattle).

Table 4 specifically examines the cumulative probability of death among patients younger than 65 years of age at diagnosis. In non-expansion states, 2008–2010 1-year cumulative probability of death was 9% higher than in expansion states (HR 1.09, 95% CI: 0.97–1.22). After expansion, the 1-year cumulative probability of death was 23% higher in non-expansion states compared to expansion states (HR 1.23, 95% CI: 1.09–1.40); however, these differences were not statistically significant. Table 5 examines the cumulative probability of death among patients 65 years of age or older at diagnosis. For these patients, the 2008–2010 1-year cumulative probability of death in non-expansion states was 13% higher than in expansion states (HR 1.13, 95% CI: 1.03–1.23). The post-expansion period cumulative probability of death is relatively unchanged at 14% (HR 1.14, 95% CI: 1.04–1.26). In both the younger than age 65 and age 65 and older cohorts, similar to the overall GBM population, no significant change is seen in the cumulative probability of death based on age, sex, race/ethnicity, or insurance status over these time periods. The sequential models indicate that there was no contribution of these factors to differences in survival between residence in expansion versus non-expansion states in the pre-ACA period. In the post-ACA period, the survival difference is larger and seems to be slightly attributed to treatment. A summary of the 1-year cumulative probability of death estimates by state expansion status and expansion time periods is also presented in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Multivariable Adjusted Hazard Ratios (HRs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) of 1-Year Overall Cumulative Probability of Death for Patients Aged 0–64 diagnosed With Glioblastoma in All Included Statesa, by Period of Diagnosis (2008–2010 and 2014–2016

| Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | Interaction P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2010 | 2014–2016 | ||||

| N = 4116 | N = 4406 | ||||

| No. of deaths | HR (95% CI) | No. of deaths | HR (95% CI) | ||

| ACA status | .1519 | ||||

| Expansion states | 440 | Reference | 349 | Reference | |

| Non-expansion states | 1348 | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | 1214 | 1.23 (1.09–1.40) | |

| Age category, years | .792 | ||||

| 0–19 | 44 | Reference | 46 | Reference | |

| 20–39 | 85 | 0.51 (0.36–0.74) | 77 | 0.51 (0.35–0.74) | |

| 40–64 | 1659 | 1.08 (0.80–1.47) | 1440 | 1.00 (0.74–1.35) | |

| Sex | .3405 | ||||

| Male | 1100 | Reference | 946 | Reference | |

| Female | 688 | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) | 617 | 0.98 (0.88–1.08) | |

| Race | .5618 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1380 | Reference | 1161 | Reference | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 142 | 0.98 (0.81–1.17) | 117 | 0.85 (0.70–1.04) | |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 6 | 0.64 (0.29–1.45) | 8 | 1.52 (0.75–3.06) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander | 60 | 0.63 (0.49–0.82) | 64 | 0.74 (0.57–0.95) | |

| Hispanic (all races) | 199 | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) | 212 | 0.88 (0.76–1.03) | |

| Non-Hispanic unknown race | <5 | 0.13 (0.02–0.90) | <5 | 0.18 (0.02–1.27) | |

| Insurance status | .3953 | ||||

| Uninsured | 124 | 1.03 (0.85–1.24) | 67 | 1.11 (0.86–1.43) | |

| Any Medicaid | 272 | 1.21 (1.05–1.38) | 306 | 1.19 (1.04–1.37) | |

| Non-Medicaid insured | 1144 | Reference | 975 | Reference | |

| Insured/No specifics | 203 | 1.01 (0.87–1.17) | 154 | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | |

| Insurance status unknown | 45 | 0.73 (0.53–0.99) | 61 | 1.00 (0.76–1.33) | |

| Tumor size at diagnosis | .9292 | ||||

| ≤45 mm | 692 | Reference | 648 | Reference | |

| >45 mm | 769 | 1.20 (1.08–1.33) | 663 | 1.19 (1.07–1.33) | |

| Unknown | 327 | 0.95 (0.83–1.09) | 252 | 0.84 (0.72–0.98) | |

Cox regression models stratified by radiation and adjusted for surgery and chemotherapy.

aAlaska (Natives), California, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan (Detroit), New Jersey, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington (Seattle).

Table 5.

Multivariable-Adjusted Hazard Ratios (HRs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) of 1-Year Overall Cumulative Probability of Death for Patients Aged 65 and Older Diagnosed With Glioblastoma in All Included Statesa, by Period of Diagnosis (2008–2010 and 2014–2016)

| Pre-expansion | Post-expansion | Interaction P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008–2010 | 2014–2016 | ||||

| N = 3887 | N = 4640 | ||||

| No. of deaths | HR (95% CI) | No. of deaths | HR (95% CI) | ||

| ACA status | .9745 | ||||

| Expansion states | 689 | Reference | 601 | Reference | |

| Non-expansion states | 2300 | 1.13 (1.03–1.23) | 2353 | 1.14 (1.04–1.26) | |

| Sex | .2496 | ||||

| Male | 1599 | Reference | 1635 | Reference | |

| Female | 1390 | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 1319 | 0.94 (0.87–1.01) | |

| Race | .489 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2498 | Reference | 2438 | Reference | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 140 | 0.89 (0.75–1.06) | 121 | 0.77 (0.64–0.92) | |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native | 5 | 0.48 (0.20–1.15) | 6 | 1.09 (0.49–2.44) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander | 103 | 0.75 (0.62–0.92) | 128 | 0.84 (0.70–1.01) | |

| Hispanic (all races) | 235 | 0.97 (0.85–1.12) | 257 | 0.93 (0.82–1.07) | |

| Non-Hispanic unknown race | 8 | 1.12 (0.55–2.28) | <5 | 0.69 (0.26–1.85) | |

| Insurance status | .1665 | ||||

| Uninsured | 19 | 0.79 (0.50–1.25) | 19 | 1.08 (0.68–1.70) | |

| Any Medicaid | 227 | 0.94 (0.81–1.08) | 194 | 1.02 (0.87–1.19) | |

| Non-Medicaid insured | 1983 | Reference | 2024 | Reference | |

| Insured/No specifics | 648 | 1.01 (0.92–1.10) | 611 | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) | |

| Insurance status unknown | 112 | 0.72 (0.59–0.89) | 106 | 1.03 (0.84–1.27) | |

| Tumor size at diagnosis | .1577 | ||||

| ≤45 mm | 1237 | Reference | 1299 | Reference | |

| >45 mm | 1208 | 1.25 (1.16–1.36) | 1203 | 1.15 (1.06–1.24) | |

| Unknown | 544 | 1.07 (0.97–1.19) | 452 | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | |

Cox regression models stratified by radiation and adjusted for surgery and chemotherapy.

aAlaska (Natives), California, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan (Detroit), New Jersey, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington (Seattle).

Figure 1.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the 1-year cumulative probability of death in non-expansion states compared to expansion states by time period and age group.

Discussion

Among possible health policy priorities, the ACA focused most strongly on access to healthcare through expanded health insurance,16 an essential element in the care of neuro-oncologic disease. Our data suggest that the ACA may have been effective in decreasing the rate of uninsured patients with GBM, particularly in states which expanded Medicaid. An increased rate of patients with GBM undergoing neurosurgical intervention in expansion states compared to non-expansion states may be related to improved access to care in the post-ACA period. But improved health insurance coverage to care did not clearly improve survival among the entire population with GBM.

Particularly in the group of patients aged 65 and older at diagnosis, there was virtually no change in outcomes between patients in expansion and non-expansion states. The lack of change among this older population may be explained by the ubiquity of Medicare insurance, which at age 65 for eligible individuals confers coverage for high-quality specialty care in all US states. While Medicare beneficiaries may still face barriers in receiving care despite health coverage, access to care among Medicare beneficiaries is typically superior to those who have Medicaid insurance.17

However, access to care in the US population younger than 65 is more heterogeneous: Most younger individuals obtain health insurance through their employer, through Medicaid, or through private plans on the non-group market.18 Prior to the implementation of the ACA, it was this younger population with the most tenuous access to care. Policies such as the individual market exchanges and the Medicaid expansion were focused on expanding health coverage to those younger than age 65 while Medicare eligibility was not impacted. Our study shows that in this younger patient population with GBM, there was no statistically significant difference in survival between expansion and non-expansion states over time, but a trend exists which requires further study to better understand. Such a trend toward improved survival could be explained by fewer uninsured patients younger than age 65 in expansion states and thus improved access to care for this group. Another possibility is that expansion states may experience a proportionally greater general improvement in the quality of care secondary to the ACA’s other impacts to the health system as a whole.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our study include the use of a well-accepted and comprehensive population-based database that spans across the country. The strength of SEER allows us to make inferences about a disease with relatively low incidence, though even with 25 784 patients, especially when divided among time periods and demographic groups, statistical power was still limited in this study.

An unfortunate strength of this study is that the standard of care for glioblastoma did not change significantly between 2008 and 2016. An alternating electric field therapy device was approved in 2011 for recurrent GBM and in late 2015 for new GBM, but the adoption rate of this therapeutic is low and survival advantage is limited.19,20

A final strength is the clarity of an essentially natural experiment that was created by the National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, a 2012 Supreme Court ruling that made the ACA’s Medicaid expansion optional for states, allowing us to assess the impacts of a policy change among relatively similar US populations.

But the complexity of the early expansion period presents a limitation to our study. Several states (and DC) chose to expand Medicaid between 2011 and 2014 in very different and limited patient populations that we are not able to isolate in the SEER database. Consequently, making any assessment of that time period as it relates to access to care and clinical outcomes is difficult requiring us to exclude this period from our analyses.

The last limitation in our study is the consolidation of patients with Medicare insurance and private insurance by the SEER database, which makes it difficult to parse out differences in demographics and outcomes between these heterogeneous patient populations. Our study, therefore, is limited to understanding differences between the Medicaid insured population and the otherwise insured population (with some data on the uninsured as well).

Conclusions

In this study of 25 784 patients diagnosed with GBM between 2008 and 2016, the uninsured rate dropped among patients in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA and more patients had access to neurosurgical care. However, there was no clear overall change in 1-year survival post-expansion between those residing in expansion states compared to those in non-expansion states. Additional studies should be undertaken to better understand whether trends toward improved survival in the population younger than age 65 which did not reach statistical significance in this study are borne out in the more extensive investigation.

Funding

The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC), National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP006344; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201800032I awarded to the University of California, San Francisco, contract HHSN261201800015I awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201800009I awarded to the Public Health Institute, Cancer Registry of Greater California. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the State of California, Department of Public Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Authorship statement. Experimental design: N.M., D.L.O., E.J.S.R., S.L.G., and R.T; analysis/interpretation of data: N.M., D.L.O., E.J.S.R., W.J.T., S.L.G., and R.T.; manuscript writing and editing: N.M., D.L.O., E.J.S.R., W.J.T., S.L.G., and R.T.

References

- 1. Cantrell JN, Waddle MR, Rotman M, et al. . Progress toward long-term survivors of glioblastoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(7):1278–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perkins A, Liu G. Primary brain tumors in adults: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(3):211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map 2019; https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/. Accessed November 16, 2019.

- 4. Golberstein E, Gonzales G, Sommers BD. California’s early ACA expansion increased coverage and reduced out-of-pocket spending for the state’s low-income population. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1688–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):944–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jemal A, Lin CC, Davidoff AJ, Han X. Changes in insurance coverage and stage at diagnosis among nonelderly patients with cancer after the affordable care act. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(35): 3906–3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Soni A, Sabik LM, Simon K, Sommers BD. Changes in insurance coverage among cancer patients under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(1):122–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Han X, Yabroff KR, Ward E, Brawley OW, Jemal A. Comparison of insurance status and diagnosis stage among patients with newly diagnosed cancer before vs after implementation of the patient protection and affordable care act. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12): 1713–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rong X, Yang W, Garzon-Muvdi T, et al. . Influence of insurance status on survival of adults with glioblastoma multiforme: a population-based study. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3157–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Incidence – SEER 18 Regs Custom Data (with additional treatment fields), Nov 2018 Sub (1975–2016 varying). National Cancer Institute, Surveillance Research Program; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gomez SL, Le GM, West DW, Satariano WA, O’Connor L. Hospital policy and practice regarding the collection of data on race, ethnicity, and birthplace. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1685–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gomez SL, Satariano W, Le GM, Weeks P, McClure L, West DW. Variability among hospitals and staff in collection of race, ethnicity, birthplace, and socioeconomic information in the greater San Francisco Bay Area. J Registry Manag. 2009;36(4):105–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adamo MB, Johnson C, Ruhl J, Dickie L. 2010SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Insurance Recode (2007+). National Cancer Institute https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/variables/seer/insurance-recode/. Accessed November 22, 2019.

- 15. National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Population-Based Cancer Survival Statistics Overview. https://surveillance.cancer.gov/survival/. Accessed December 11, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glied S, Ma S, Borja AA.. Effect of the Affordable Care Act on Health Care Access. The Commonwealth Fund; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holgash K, Heberlein M. Physician acceptance of new Medicaid patients: what matters and what doesn’t. In: Affairs H, ed. Health Affairs Blog. Vol 2019, April 10 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190401.678690/full/. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garfield R, Orgera K, Damico A.. The Uninsured and the ACA: A Primer. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/report/the-uninsured-and-the-aca-a-primer-key-facts-about-health-insurance-and-the-uninsured-amidst-changes-to-the-affordable-care-act/. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wick W. TTFields: where does all the skepticism come from? Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(3):303–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner AA, et al. . Maintenance therapy with tumor-treating fields plus temozolomide vs temozolomide alone for glioblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(23):2535–2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]