Abstract

Background

Resilience can be defined as maintaining or regaining mental health during or after significant adversities such as a potentially traumatising event, challenging life circumstances, a critical life transition or physical illness. Healthcare students, such as medical, nursing, psychology and social work students, are exposed to various study‐ and work‐related stressors, the latter particularly during later phases of health professional education. They are at increased risk of developing symptoms of burnout or mental disorders. This population may benefit from resilience‐promoting training programmes.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions to foster resilience in healthcare students, that is, students in training for health professions delivering direct medical care (e.g. medical, nursing, midwifery or paramedic students), and those in training for allied health professions, as distinct from medical care (e.g. psychology, physical therapy or social work students).

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, 11 other databases and three trial registries from 1990 to June 2019. We checked reference lists and contacted researchers in the field. We updated this search in four key databases in June 2020, but we have not yet incorporated these results.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing any form of psychological intervention to foster resilience, hardiness or post‐traumatic growth versus no intervention, waiting list, usual care, and active or attention control, in adults (18 years and older), who are healthcare students. Primary outcomes were resilience, anxiety, depression, stress or stress perception, and well‐being or quality of life. Secondary outcomes were resilience factors.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies, extracted data, assessed risks of bias, and rated the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach (at post‐test only).

Main results

We included 30 RCTs, of which 24 were set in high‐income countries and six in (upper‐ to lower‐) middle‐income countries. Twenty‐two studies focused solely on healthcare students (1315 participants; number randomised not specified for two studies), including both students in health professions delivering direct medical care and those in allied health professions, such as psychology and physical therapy. Half of the studies were conducted in a university or school setting, including nursing/midwifery students or medical students. Eight studies investigated mixed samples (1365 participants), with healthcare students and participants outside of a health professional study field.

Participants mainly included women (63.3% to 67.3% in mixed samples) from young adulthood (mean age range, if reported: 19.5 to 26.83 years; 19.35 to 38.14 years in mixed samples). Seventeen of the studies investigated group interventions of high training intensity (11 studies; > 12 hours/sessions), that were delivered face‐to‐face (17 studies). Of the included studies, eight compared a resilience training based on mindfulness versus unspecific comparators (e.g. wait‐list).

The studies were funded by different sources (e.g. universities, foundations), or a combination of various sources (four studies). Seven studies did not specify a potential funder, and three studies received no funding support.

Risk of bias was high or unclear, with main flaws in performance, detection, attrition and reporting bias domains.

At post‐intervention, very‐low certainty evidence indicated that, compared to controls, healthcare students receiving resilience training may report higher levels of resilience (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.43, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.07 to 0.78; 9 studies, 561 participants), lower levels of anxiety (SMD −0.45, 95% CI −0.84 to −0.06; 7 studies, 362 participants), and lower levels of stress or stress perception (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.48 to −0.09; 7 studies, 420 participants). Effect sizes varied between small and moderate. There was little or no evidence of any effect of resilience training on depression (SMD −0.20, 95% CI −0.52 to 0.11; 6 studies, 332 participants; very‐low certainty evidence) or well‐being or quality of life (SMD 0.15, 95% CI −0.14 to 0.43; 4 studies, 251 participants; very‐low certainty evidence).

Adverse effects were measured in four studies, but data were only reported for three of them. None of the three studies reported any adverse events occurring during the study (very‐low certainty of evidence).

Authors' conclusions

For healthcare students, there is very‐low certainty evidence for the effect of resilience training on resilience, anxiety, and stress or stress perception at post‐intervention.

The heterogeneous interventions, the paucity of short‐, medium‐ or long‐term data, and the geographical distribution restricted to high‐income countries limit the generalisability of results. Conclusions should therefore be drawn cautiously. Since the findings suggest positive effects of resilience training for healthcare students with very‐low certainty evidence, high‐quality replications and improved study designs (e.g. a consensus on the definition of resilience, the assessment of individual stressor exposure, more attention controls, and longer follow‐up periods) are clearly needed.

Plain language summary

Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare students

Background Healthcare students (e.g. medical, nursing, midwifery, paramedic, psychology, physical therapy, or social work students) have a high academic work load, are required to pass examinations and are exposed to human suffering. This can adversely affect their physical and mental health. Interventions to protect them against such stresses are known as resilience interventions. Previous systematic reviews suggest that resilience interventions can help students cope with stress and protect them against adverse consequences on their physical and mental health.

Review question Do psychological interventions designed to foster resilience improve resilience, mental health, and other factors associated with resilience in healthcare students?

Search dates The evidence is current to June 2019. The results of an updated search of four key databases in June 2020 have not yet been included in the review.

Study characteristics We found 30 randomised controlled trials (studies in which participants are assigned to either an intervention or a control group by a procedure similar to tossing a coin). The studies evaluated a range of resilience interventions in participants aged on average between 19 and 38 years.

Healthcare students were the focus of 22 studies, with a total of 1315 participants (not specified for two studies). Eight studies included mixed samples (1365 participants) of healthcare students and non‐healthcare students.

Eight of the included studies compared a mindfulness‐based resilience intervention (i.e. an intervention fostering attention on the present moment, without judgements) versus unspecific comparators (e.g. wait‐list control receiving the training after a waiting period). Most interventions were performed in groups (17/30), with high training intensity of more than 12 hours or sessions (11/30), and were delivered face‐to‐face (i.e. with direct contact and face‐to‐face meetings between the intervention provider and the participants; 17/30).

The included studies were funded by different sources (e.g. universities, foundations), or a combination of various sources (four studies). Seven studies did not specify a potential funder, and three studies received no funding support.

Certainty of the evidence A number of things reduce the certainty about whether resilience interventions are effective. These include limitations in the methods of the studies, different results across studies, the small number of participants in most studies, and the fact that the findings are limited to certain participants, interventions and comparators.

Key results Resilience training for healthcare students may improve resilience, and may reduce symptoms of anxiety and stress immediately after the end of treatment. Resilience interventions do not appear to reduce depressive symptoms or to improve well‐being. However, the evidence from this review is limited and very uncertain. This means that we currently have very little confidence that resilience interventions make a difference to these outcomes and that further research is very likely to change the findings.

Very few studies reported on the short‐ and medium‐term impact of resilience interventions. Long‐term follow‐up assessments were not available for any outcome. Studies used a variety of different outcome measures and intervention designs, making it difficult to draw general conclusions from the findings. Potential adverse events were only examined in four studies, with three of them showing no undesired effects and one reporting no results. More research is needed, of high methodological quality and with improved study designs.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Resilience interventions versus control conditions for healthcare students.

| Resilience interventions versus control conditions for healthcare students | ||||||

|

Patient or population: healthcare students, including students in training for health professions delivering direct medical care (e.g. medical students, nursing students), and allied health professions as distinct from medical care (e.g. psychology students, social work students); aged 18 years and older, irrespective of health status Setting: any setting of health professional education (e.g. medical school, nursing school, psychology or social work department at university) Intervention: any psychological intervention focused on fostering resilience or the related concepts of hardiness or post‐traumatic growth by strengthening well‐evidenced resilience factors that are thought to be modifiable by training (see Appendix 3), irrespective of content, duration, setting or delivery mode Comparison: no intervention, wait‐list control, treatment as usual (TAU), active control, attention control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control conditions | Risk with resilience interventions | |||||

|

Resilience

Measured by: investigators measured resilience using different instruments; higher scores mean higher resilience Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

‐ | The mean resilience score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.43 standard deviations higher (0.07 higher to 0.78 higher) | ‐ | 561 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | SMD of 0.43 represents a moderate effect size (Cohen 1988b)b |

|

Mental health and well‐being: anxiety

Measured by: investigators measured anxiety using different instruments; lower scores mean lower anxiety Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

‐ | The mean anxiety score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.45 standard deviations lower (0.84 lower to 0.06 lower) | ‐ | 362 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | SMD of 0.45 represents a moderate effect size (Cohen 1988b)b |

|

Mental health and well‐being: depression

Measured by: investigators measured depression using different instruments; lower scores mean lower depression Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

‐ | The mean depression score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.20 standard deviations lower (0.52 lower to 0.11 higher) | ‐ | 332 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd | SMD of 0.20 represents a small effect size (Cohen 1988b)b |

|

Mental health and well‐being: stress or stress perception: Measured by: investigators measured stress or stress perception using different instruments; lower scores mean lower stress or stress perception Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

‐ | The mean stress or stress perception score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.28 standard deviations lower (0.48 lower to 0.09 lower) | ‐ | 420 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe | SMD of 0.28 represents a small effect size (Cohen 1988b)b |

|

Mental health and well‐being: well‐being or quality of life: Measured by: investigators measured well‐being or quality of life using different instruments; higher scores mean higher well‐being or quality of life Timing of outcome assessment: post‐intervention |

‐ | The mean well‐being or quality of life score in the intervention groups was, on average, 0.15 standard deviations higher (0.14 lower to 0.43 higher) | ‐ | 251 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowf | SMD of 0.15 represents a small effect size (Cohen 1988b)b |

| Adverse events | There were no adverse events reported in association with study participation in 3 of 4 studies measuring potential adverse events.g | ‐ | 566 (3 RCTs)h |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowi | ‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection bias, high and unclear risk of performance, detection and attrition bias), by one level due to unexplained inconsistency (I2 = 75%), and by one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain interventions (e.g. group setting, face‐to‐face delivery, moderate and high intensity, unspecified theoretical foundation) and comparators (no intervention, wait‐list)).

bAccording to Cohen 1988b, a standardised mean difference (SMD) of 0.2 represents a small difference (i.e. small effect size), 0.5 a moderate difference, and 0.8 a large difference. cDowngraded by two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection bias, high and unclear risk of detection and attrition bias, high risk of performance bias), by one level due to unexplained inconsistency (I2 = 66%), and by one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain participants (medical students), interventions (e.g. group setting, moderate and high intensity) and comparators (no intervention, wait‐list)). dDowngraded by two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection bias, high and unclear risk of detection bias, high risk of performance and attrition bias), by one level due to unexplained inconsistency (I2 = 45%), by one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain participants (medical students), interventions (e.g. group and individual setting, low and high intensity) and comparators (no intervention, wait‐list)), and by two levels due to imprecision (< 400 participants; 95% CI wide and inconsistent). eDowngraded by two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection bias, high and unclear risk of detection bias, high risk of performance, attrition and reporting bias), and by one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain participants (medical and nursing students), interventions (group and individual setting, low and high intensity, mindfulness and unspecific theoretical foundation) and comparators (no intervention, wait‐list)). fDowngraded by two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection and detection bias, high and unclear risk of attrition bias, high risk of performance bias), by one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain interventions (group setting, face‐to‐face and combined delivery, high intensity)), and by two levels due to imprecision (< 400 participants; 95% CI and inconsistent).

gKötter 2016 also assessed adverse events but did not report the respective data in the report. hFor Galante 2018, subgroup data in healthcare students were not available; number of participants in total sample at post‐test (CORE‐OM data) was 482. iDowngraded by two levels due to study limitations (unclear risk of selection and detection bias, unclear and high risk of attrition bias, high risk of performance and other bias (no systematic and validated assessment of adverse events)), and by one level due to indirectness (studies limited to certain interventions (individual setting, face‐to‐face, mindfulness based) and comparators (TAU)).

Background

For a description of abbreviations used in this review, please see Appendix 1.

Description of the condition

Since the introduction of Antonovsky’s salutogenesis as a basis for health promotion (Antonovsky 1979), and the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986), the concept of resilience has stimulated extensive research. Resilience describes the phenomenon under which an individual does not, or only temporarily, experiences mental health problems despite being subjected to psychological or physical stressors of short (acute) or long (chronic) duration (Kalisch 2015; Kalisch 2017). By definition, resilience always presupposes the exposure to substantial risk or adversity (Earvolino‐Ramirez 2007; Jackson 2007; Luthar 2000; Masten 2001).

Stressor exposure in healthcare students and its consequences

Healthcare students are exposed to a large number of academic, clinical and psychosocial stressors. Substantial academic stressors include, for example, excessive academic workload (e.g. long hours of study, volume of information, difficult academic work), difficulties with studying and time management, competition with peers, examinations (e.g. high frequency), and fear of failing (Edwards 2010; Gazzaz 2018; Hill 2018). Further categories of stressor exposure may include social stressors such as conflicts with work‐life balance and relationship management, financial concerns, or uncertainty about the future (Chang 2012; Gazzaz 2018; Santen 2010). In addition to typical life changes during the transition from training (e.g. nursing or medical school) to (clinical) practice, healthcare students also have to adapt to challenges that are specific to their chosen field of work. Due to patient contact in later phases of training, they are exposed to patient‐related stressors such as exposure to human suffering and death (Hill 2018). Furthermore, clinical stressors identified among students and trainees in the healthcare sector include, for example, lack of practical skills, a theory‐to‐practice gap, tense atmosphere among clinical staff and negative attitudes of healthcare professionals, being criticised in front of staff and patients, or hospital ward rotations (Dyrbye 2009; Edwards 2010; Evans 2004; Hill 2018).

Chronic stressor exposure during health professional education has the potential to impact on the students' physical and mental health; for example, medical and nursing students have reported debilitating sleep disorders (Azad 2015; Belingheri 2020). Health professional education is perceived as stressful by many students, with many reporting increased levels of perceived stress (Edwards 2010; Fares 2016; Foster 2018; Heinen 2017; Jacob 2013; Wilks 2010). Healthcare students, especially medical students, are at increased risk of developing symptoms of burnout, such as high emotional exhaustion (Cecil 2014; Dyrbye 2009; Dyrbye 2016; Fares 2016; Santen 2010), and stress‐related mental disorders such as depression (Bunevicius 2008; Compton 2008; Dyrbye 2006; Mao 2019; Tung 2018) and anxiety (Bunevicius 2008; Dyrbye 2006; Mao 2019). The experience of stressors and the resulting health impact may negatively affect students' academic (e.g. grades) and clinical performance (e.g. decline in empathy) (Gazzaz 2018; Kötter 2017; Neumann 2011; Yamada 2014; Ye 2018), and could possibly affect also the high attrition rates found among healthcare students (Hamshire 2019) and new graduates (Pine 2007), as demonstrated by some studies (Dyrbye 2011).

Overall, based on these findings, the concept of resilience has become increasingly important for health professional education in recent years (Eley 2014; Hodges 2008; McAllister 2009; Pines 2012; Sanderson 2017; Stephens 2013; Tempski 2012; Thomas 2016; Waddell 2015; Wright 2019).

Definition of resilience

Three different approaches have been discussed in the definition of resilience (Hu 2015; Kalisch 2015). Trait resilience refers to resilience defined as personal resources or static, positive personality characteristics that enhance individual adaptation (Block 1996; Nowack 1989; Wagnild 1993). This approach has been superceded largely by a view of resilience as an outcome rather than a static personality trait (Kalisch 2015; Mancini 2009), i.e. mental health despite significant stress or trauma. According to this outcome‐oriented definition, the positive outcome of resilience is partially determined by several resilience factors (Kalisch 2015). To date, a large range of genetic, psychological, social and environmental factors have been discussed in resilience research that often overlap and may interact (Bengel 2012; Bonanno 2013; Carver 2010; Connor 2006; Earvolino‐Ramirez 2007; Feder 2011; Forgeard 2012; Haglund 2007; Iacoviello 2014; Kuiper 2012; Mancini 2009; Michael 2003; Ozbay 2007; Rutten 2013; Sapienza 2011; Sarkar 2014; Southwick 2005; Southwick 2012; Stewart 2011; Wu 2013; Zauszniewski 2010). Psychosocial resilience factors that are well‐evidenced according to the current state of knowledge and thought to be modifiable include: meaning or purpose in life, a sense of coherence, positive emotions, hardiness, self‐esteem, active coping, self‐efficacy, optimism, social support, cognitive flexibility (including positive reappraisal and acceptance), and religiosity or spirituality or religious coping (see Appendix 2: level 1). Most recently, resilience has been conceptualised as a multidimensional and dynamic process (Johnston 2015; Kalisch 2015; Kent 2014; Mancini 2009; Norris 2009; Rutten 2013; Sapienza 2011; Southwick 2012). This resilient process is characterised either by a trajectory of undisturbed mental health during or after adversities, or temporary dysfunction followed by successful recovery (Kalisch 2015). In general, resilience is viewed as the outcome of an interaction between the individual and his or her environment (Cicchetti 2012; Rutten 2013), which may be influenced through personal (e.g. optimism) as well as environmental resources (e.g. social support) (Haglund 2007; Iacoviello 2014; Kalisch 2015; Southwick 2005; Wu 2013). As such, resilience is modifiable and can be improved by interventions (Bengel 2012; Connor 2006; Southwick 2011).

Interventions to foster resilience

Interventions to foster resilience have been developed for and conducted in a variety of clinical and non‐clinical populations using various formats, such as multimedia programmes or face‐to‐face settings, and have been delivered in a group or individual context (see Bengel 2012 and Southwick 2011 for an overview). To date, several resilience‐training programmes that focus specifically on fostering resilience in healthcare students have been tested (Anderson 2017; Peng 2014). However, the empirical evidence for the efficacy of these interventions is still unclear and requires further research.

Description of the intervention

There is currently little consensus about when to consider a programme as ‘resilience training’, or what components are needed for effective programmes (Leppin 2014). The diversity across resilience‐training programmes in their theoretical assumptions, operationalisation of the construct, and inclusion of core components reflect the current state of knowledge (Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016), with leading guidelines still under discussion (compare Kalisch 2015; Robertson 2015).

Most training programmes, whether individual or group‐based, are implemented face‐to‐face. Alternative formats include online interventions or combinations of different formats. Resilience‐training programmes often use methods such as discussions, role plays, practical exercises and homework to reinforce training content. They usually contain a psycho‐educative element to provide information on the concept of resilience, or specific training elements (e.g. cognitive restructuring).

In general, resilience interventions are based on different psychotherapeutic approaches: cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT; Abbott 2009); acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Ryan 2014); mindfulness‐based therapy (Geschwind 2011); attention and interpretation therapy (AIT; Sood 2014); problem‐solving therapy (Bekki 2013), as well as stress inoculation (Farchi 2010). A number of training programmes focus on fostering single or multiple psychosocial resilience factors (Kanekar 2010), without being assignable to a certain approach. Few interventions base their work on a defined resilience model (Schachman 2004; Steinhardt 2008).

How the intervention might work

Depending on the underlying resilience concept, resilience interventions target different resources and skills. The theoretical foundations of training programmes and the hypotheses on how they might maintain or regain mental health are as diverse as their content. Currently, no empirically‐validated theoretical framework exists that outlines the mode of action of resilience interventions (Bengel 2012; Leppin 2014).

As resilience as an outcome is determined by several potentially modifiable resilience factors (see Description of the condition), resilience interventions might work by strengthening these factors (see Appendix 3 for examples of possible training methods). However, depending on the underlying theoretical foundation, there are different theories of change on how certain factors and hence resilience might be affected.

From a cognitive‐behavioural perspective, stress‐related mental dysfunctions (e.g. depression) are considered to be the result of dysfunctional thinking (Beck 2011; Benjamin 2011). When confronted with adversity, people show maladaptive behavioural responses or experience negative mood states, or both, due to irrational cognition (Beck 1976; Ellis 1975). This is in line with other stress and resilience theories, which assume that it is not the stressor itself, but its cognitive appraisal that may lead to stress reactions (Kalisch 2015; Lazarus 1987). Modifying cognitive processes into more adaptive patterns of thought will therefore probably produce more adaptive responses to stress (Beck 1964). By challenging an individual’s maladaptive thoughts, and by teaching coping strategies, CBT‐based resilience interventions might be beneficial in promoting the resilience factors of cognitive flexibility and active coping.

As one form of CBT, stress inoculation therapy is based on the assumption that exposing individuals to milder forms of stress can strengthen coping strategies and the individual’s confidence in using his or her coping repertoire (Meichenbaum 2007). Resilience‐training programmes grounded in stress inoculation therapy might therefore foster resilience by enhancing factors such as self‐efficacy.

Problem‐solving therapy is closely related to CBT and based on problem‐solving theory. According to the problem‐solving model of stress and adaptation, effective problem‐solving can attenuate the negative effects of stress and adversity on well‐being by moderating or mediating (or both) the effects of stressors on emotional distress (Nezu 2013). Resilience interventions based on problem‐solving that enhance an individual’s positive problem orientation and planful problem‐solving might foster participants’ psychological adaptation to stress by increasing the resilience factor of active coping.

According to ACT (Hayes 2004; Hayes 2006), psychopathology is primarily the consequence of psychological inflexibility (Hayes 2006), which is also relevant when an individual is confronted with stressors. By teaching acceptance and mindfulness skills on the one hand (e.g. being in contact with the present moment), and commitment and behaviour‐change skills on the other (e.g. values, committed action), several resilience factors might be fostered in ACT‐based resilience interventions (e.g. cognitive flexibility, purpose in life). In particular, the acceptance of a full range of emotions taught in ACT might result in a better adjustment to stressful conditions.

In mindfulness‐based therapy (e.g. mindfulness‐based stress reduction (MBSR; Stahl 2010); AIT (Sood 2010)), mindfulness is characterised by the nonjudging awareness of the present moment and its accompanying mental phenomena (i.e. body sensations, thoughts and emotions). Since practitioners learn to accept whatever occurs in the present moment, they are thought to adapt more efficiently to stress (Grossman 2004; Shapiro 2005). As being more aware of the 'here and now' may enhance the sensitivity to positive aspects in life, mindfulness‐based resilience interventions might also help participants to gain a brighter outlook for the future (i.e. optimism) or to experience positive emotions more regularly. Teaching mindfulness might also increase participants’ cognitive flexibility by learning to accept negative situations and emotions.

Independently of the underlying theory, resilience training might work differently depending on the respective 'delivery format' and 'intervention setting' (Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016). For example, interventions implemented face‐to‐face could work better than online formats in increasing resilience, due to the more direct contact between trainers and participants (Vanhove 2016), which might also increase compliance. Resilience training in an individual setting could be more efficient than group‐based interventions, as trainers might be better able to attend to participants’ individual needs and provide feedback more easily (Vanhove 2016). On the other hand, group‐based interventions could enhance participants’ social resources. No previous review has examined the role of training duration on effect sizes of resilience interventions. As participants have the opportunity to apply the taught skills in daily life, high‐intensity resilience interventions that include weekly sessions over several weeks (e.g. combined with homework assignments or daily practice) could be more efficient than low‐intensity training (e.g. a single session). Joyce 2018, who examined the role of the theoretical foundation of resilience interventions for the first time, found positive effect sizes on resilience for CBT‐based, mindfulness‐based and mixed interventions (i.e. CBT and mindfulness) compared to control. However, differences in the effects of resilience training based on other theoretical foundations have not so far been considered.

Why it is important to do this review

A large number of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses have investigated various forms of interventions to foster healthcare students' mental health, such as stress management, mentoring programmes, emotional intelligence interventions and mindfulness‐based training to reduce or prevent burnout, and crisis‐focused programmes (see Appendix 4). Although some of these reviews also identified interventions to foster resilience (e.g. Griffiths 2019), the primary review question did not specifically refer to such programmes.

A considerable number of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of interventions to foster resilience (see Appendix 4) have synthesised the efficacy of resilience‐training programmes in clinical and non‐clinical adult populations (Bauer 2018; Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Massey 2019; Milne 2016; Pallavicini 2016; Pesantes 2015; Petriwskyj 2016; Reyes 2018; Robertson 2015; Skeffington 2013; Townshend 2016; Vanhove 2016; Van Kessel 2014; Wainwright 2019), or at least have searched for 'resilience' and related constructs (Deady 2017; Tams 2016). In a recent Cochrane Review, our group synthesised the evidence on the efficacy of resilience training in healthcare professionals (Kunzler 2020). There are so far only four relevant meta‐analyses (Joyce 2018; Kunzler 2020; Leppin 2014; Vanhove 2016). Previous reviews agree in their conclusion that resilience interventions can generally improve resilience, mental health and (job) performance. Nevertheless, there are some methodological and quality differences between the reviews, which complicate statements about the efficacy of resilience training or result in a variety of effect sizes. These include, for example, heterogeneous eligibility criteria and definitions of resilience training, rather simple and limited search strategies, the lack of a review protocol or PROSPERO registration for most reviews, and different guidelines for the conduct and reporting of the review.

Four systematic reviews of healthcare students (see Appendix 4) have synthesised evidence on the efficacy of resilience‐training programmes in this target group (Gilmartin 2017; McGowan 2016; Rogers 2016; Sanderson 2017), with Sanderson 2017 not focusing only on resilience interventions. One other review (Pezaro 2017) and a meta‐analysis (Lo 2018) also searched for 'resilience'. The six publications either investigated healthcare students such as medical students (Lo 2018) or combinations of healthcare students and healthcare professionals (i.e. with completed training) (Gilmartin 2017). Overall, they found mixed results for the efficacy of resilience‐training programmes. On the one hand, they identified some benefits to healthcare students, for example, in improving resilience or mental health outcomes (e.g. Gilmartin 2017; Pezaro 2017; Rogers 2016). On the other hand, as pointed out by some authors (e.g. McGowan 2016), the reviews' conclusions have been restricted by current limitations of resilience intervention research (e.g. heterogeneous definitions of resilience, and the low methodological rigour of studies). Comparable with reviews in other populations, the publications also suffer from methodological weaknesses, which limit the robustness of their findings (see Appendix 4). Most importantly, the number of RCTs included in previous reviews is rather limited (0 to 24 RCTs among 5 to 36 studies included in the six reviews), and the search period covered by the reviews is up to January 2017 (Gilmartin 2017), thus precluding any conclusions about the efficacy of resilience interventions in healthcare students that have been developed since then.

In our review, which seeks to address the methodological weaknesses of previous reviews, we were also particularly interested in psychological resilience interventions offered to this target group. The interventions had to be scientifically founded, i.e. they had to address one or more of the resilience factors stated above that are known to be associated with resilience in adults according to the state of current research (see Appendix 2: levels 1a to 1c). They also had to state the intention of promoting resilience or a related construct (hardiness, post‐traumatic growth). Lastly, the trained population had to fulfil the condition of potential stress or trauma exposure (the concept implicated for resilience), i.e. being a healthcare student (see Description of the condition), in order to clearly distinguish genuine resilience interventions from other interventions focused on fostering associated constructs such as mental health (Windle 2011a).

Resilience as a concept of prevention is highly current, and there is increasing interest worldwide in promoting mental health and preventing disease (WHO 1986; WHO 2004). Due to chronic stressor exposure in healthcare students, and the potentially negative consequences for the students’ health (see Description of the condition), healthcare students are viewed as an important target group for resilience interventions (McAllister 2009). This review therefore aims to provide further and more detailed evidence about which interventions are most likely to foster resilience and to prevent stress‐related mental health problems in healthcare students. The evidence base for this review might contribute to improving existing interventions and to facilitating the future development of training programmes. In this way, researchers, practitioners and policymakers could benefit from our work.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions to foster resilience in healthcare students, that is, students in training for health professions delivering direct medical care (e.g. medical, nursing, midwifery or paramedic students), and those in training for allied health professions, as distinct from medical care (e.g. psychology, physical therapy or social work students; see Differences between protocol and review).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs.

Types of participants

Adults aged 18 years and older, who are healthcare students, i.e. students in training for health professions delivering direct medical care (e.g. medical, nursing, midwifery or paramedic students) and those in training for allied health professions, as distinct from medical care (e.g. psychology, physical therapy, social work, counselling, occupational therapy, speech therapy, medical assistant or medical technician students).

Participants were included irrespective of health status.

At the time of the intervention, individuals had to be exposed to potential risk or stressors, which was ensured by focusing on healthcare students in this review (see Description of the condition; see Differences between protocol and review).

We included studies involving mixed samples (e.g. healthcare and non‐healthcare students) in the review. We also considered these studies in meta‐analyses (see Data synthesis) provided the data for healthcare students were reported separately or could be obtained by contacting the study authors.

Types of interventions

Any psychological resilience intervention, irrespective of content, duration, setting or delivery mode.

For the purpose of this review, we define psychological resilience interventions as follows: interventions focused on fostering resilience or the related concepts of hardiness or post‐traumatic growth, by strengthening well‐evidenced resilience factors that are thought to be modifiable by training (see above and Appendix 2; level 1). In order to use highly‐objective inclusion criteria, we considered only interventions that explicitly defined the objective of fostering resilience, hardiness, or post‐traumatic growth by using one or more of these terms in the publication (see Differences between protocol and review). We did not include studies that examined the efficacy of disorder‐specific psychotherapy (e.g. CBT for depression).

We considered the following comparators in this review: no intervention, wait‐list control, treatment as usual (TAU), active control, and attention control. We used the term ‘attention control’ for alternative treatments that mimicked the amount of time and attention received (e.g. by the trainer) in the treatment group. We also considered active controls to involve an alternative treatment (no TAU; for example, treatment developed specifically for the study), but that did not control for the amount of time and attention in the intervention group and was not attention control in a narrow sense.

Types of outcome measures

Due to the different ways in which resilience has been operationalised in previous research, resilience as an intervention outcome could not always be guaranteed in studies. We therefore also defined assessments of psychological adaptation (e.g. mental health) as primary outcomes.

Secondary outcomes included a range of psychological factors associated with resilience, according to the current state of knowledge, and were selected based on conceptual clarity and measurability (levels 1a and 1b; see Appendix 2).

Measures for the assessment of psychological resilience and psychological adaptation, as well as resilience factors, are specified on the basis of previous reviews on resilience interventions (Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016) and reviews on resilience measurements (Pangallo 2015; Windle 2011b); see Helmreich 2017 and Appendix 5, Appendix 6, Appendix 7 in this review, respectively.

We considered self‐rated and observer‐ or clinician‐rated measures, as well as study outcomes at all time points. The lack of reporting of the primary or secondary outcomes described above was not an exclusion criterion for this review.

Primary outcomes

Resilience*, measured by improvements in specific resilience scales (Bengel 2012; Earvolino‐Ramirez 2007; Pangallo 2015; Windle 2011b), such as the Resilience Scale for Adults (Friborg 2003).

-

Mental health and well‐being, subsumed into the categories below, and measured by improvements in the respective assessment scales, such as the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS‐21; Lovibond 1995). See Appendix 6 for further examples.

Anxiety*

Depression*

Stress or stress perception*

Well‐being or quality of life* (e.g. well‐being, life satisfaction, (health‐related) quality of life, vitality, vigour)

Adverse events*

Secondary outcomes

Resilience factors (Bengel 2012; Haglund 2007; Iacoviello 2014; Southwick 2005; Southwick 2012; Wu 2013), whenever they were available as outcomes, assessed by an increase in the respective instruments (e.g. Life Orientation Test ‐ Revised (LOT‐R); Scheier 1994). For further examples see Appendix 7.

Social support

Optimism

Self‐efficacy

Active coping

Self‐esteem

Hardiness (although hardiness is often used as a synonym for resilience in the literature, we conceptualised it as a resilience factor in this review. See Appendix 2.)

Positive emotions

We extracted and reported data on secondary outcomes whenever they were assessed. If possible, we calculated and reported effect sizes.

Where data were available, we used outcomes marked by an asterisk (*) to generate the ‘Summary of findings’ table. If there was insufficient information, we provided a narrative description of the evidence.

Search methods for identification of studies

We ran the first searches for this review in October 2016, based on the MEDLINE search strategy in the protocol (Helmreich 2017) before changing the inclusion criteria of the review to focus on healthcare students (see Differences between protocol and review). For the top‐up searches in June 2019, we added a new section to the original search strategy using search terms to limit the search to healthcare sector workers and students.

Electronic searches

We searched the electronic sources listed below.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 6) in the Cochrane Library, which includes the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Specialised Register (searched 26 June 2019).

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 21 June 2019).

Embase Ovid (1974 to 2019 Week 25).

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to June Week 3 2019).

CINAHL EBSCOhost (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1981 to 24 June 2019).

PSYNDEX EBSCOhost (1977 to 24 June 2019).

Web of Science Core Collection Clarivate (Science Citation Index; Social Science Citation Index; Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science; Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Science & Humanities; 1970 to 26 June 2019).

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences ProQuest (IBSS; 1951 to 25 June 2019).

Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts ProQuest (ASSIA; 1987 to 24 June 2019).

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (PQDT; 1743 to 24 June 2019).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; 2019, Issue 6), part of the Cochrane Library (searched 26 June 2019).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE; 2015, Issue 4) part of the Cochrane Library (final issue; searched 27 October 2016).

Epistemonikos (epistemonikos.org; all available years, searched 24 June 2019).

ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center; 1966 to 26 June 2019).

Current Controlled Trials now ISTRCN registry (www.isrctn.com; 1 January 1990 to 24 June 2019).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; 1 January 1990 to 24 June 2019).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; who.int/trialsearch; 1 January 1990 to 24 June 2019)

We report the search strategies for each database in Appendix 8 (up to 2016) and for the revised inclusion criteria, Appendix 9 (2016 onwards). We used the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy to identify RCTs in MEDLINE (Lefebvre 2019). We adapted the search terms and syntax for other databases. The searches were not restricted by language, publication status or publication format. We limited our search to the period January 1990 onwards, to account for the fact that the concept of resilience and its operationalisation have developed significantly over the past decades (Fletcher 2013; Hu 2015; Kalisch 2015; Pangallo 2015). Because of the lack of homogeneity for the period 1990 to 2014 (Robertson 2015), it is likely that using a broader time frame would have made it even more difficult to detect resilience‐training studies with similar resilience concepts and assessments. Moreover, it appeared plausible to concentrate on the period 1990 to the present, since the idea of resilience as an outcome and a modifiable process has only emerged in recent years, and paved the way for the development of resilience‐promoting interventions (Bengel 2009; Southwick 2011). The idea of fostering resilience by specific training was therefore relatively new (Leppin 2014), which can also be seen in the review by Macedo 2014, who searched for studies on resilience interventions every year until 2013 but only found RCTs published after 1990.

As resilience‐training programmes should be adapted to scientific findings on a regular basis, and with the current research focusing on the detection of general resilience mechanisms (Kalisch 2015; Luthar 2000), the last five years seemed especially important in synthesising the evidence on newly‐developed resilience training.

We performed a further scoping search of four key databases (CENTRAL, CINAHL EBSCOhost, PsycINFO Ovid, ClinicalTrials.gov) in June 2020 prior to the publication of this review. The results are awaiting classification and will be incorporated into the review at the next update.

Searching other resources

In addition to the electronic searches, we inspected the reference lists of all included RCTs and relevant reviews, and contacted researchers in the field as well as the authors of selected studies, to check if there were any unpublished or ongoing studies. If data were missing or unclear, we contacted the study authors.

Data collection and analysis

We report only the methods we used in successive sections in this review. We report preplanned but unused methods in Table 2.

1. Unused methods table.

| Method | Approach planned for analysis | Reason for non‐use |

| Measures of treatment effect | Dichotomous data We had planned to analyse dichotomous outcomes by calculating the risk ratio (RR) of a successful outcome (i.e. improvement in relevant variables) for each trial. We had intended to express uncertainty in each result using 95% confidence intervals (CIs). | No study provided relevant dichotomous data for any of the primary or secondary outcomes included in this review. |

| Unit of analysis issues | Cluster‐randomised trials In cluster‐randomised trials, if the clustering is ignored and the unit of analysis is different from the unit of allocation (‘unit‐of‐analysis error’) (Whiting‐O'Keefe 1984), P values may be artificially small and may result in false‐positive conclusions (Higgins 2019c). Had we encountered such cases, we would have accounted for the clustering in the data and followed the recommendations given in the literature (Higgins 2019c; White 2005). For those cluster‐randomised trials that did not report correct standard errors, we would have tried to recover correct standard errors by applying the usual formula for the variance inflation factor 1 + (M ‐ 1) ICC, where M is the average cluster size and ICC the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient (Higgins 2019c). If it had not been possible to extract ICC values from the study, we would have used the ICC of all cluster‐randomised trials in our review that investigated the same primary outcome scale in a similar setting. If this was not available, we would have used the average ICC of all other cluster‐randomised trials in our review. If no such studies were available, we would have used ICC = 0.05 as a mildly conservative guess for the primary analysis, and conducted a sensitivity analysis using ICC = 0.10. We had also planned to conduct sensitivity analyses based on the unit of randomisation as well as the ICC estimate in cluster‐randomised trials (see Sensitivity analysis). | No cluster‐RCT was identified and included in this review. |

|

Multiple treatment groups Had multiple groups in a study been relevant, we would have accounted for the correlation between the effect sizes from multi‐arm studies in a pair‐wise meta‐analysis (Higgins 2019c). We would have treated each comparison between a control group and a treatment group as an independent study. We would have multiplied the standard errors of the effect estimates by an adjustment factor to account for correlation between effect estimates. In so doing, we would have acknowledged heterogeneity between different treatment groups. |

For studies with multiple treatment groups, we considered only one intervention group to be relevant for the review and meta‐analyses, based on the independent judgement of two review authors. Thus, in a pair‐wise meta‐analysis, we did not have to account for the correlation between the effect sizes for multi‐arm studies. | |

| […] If there is an adequate evidence base, we will consider performing a network meta‐analysis (see Data synthesis). | The evidence base was insufficient to conduct a network meta‐analysis. | |

| Dealing with missing data | If standard deviations could neither be recovered from reported results nor obtained from the authors, we would have considered single imputation by means of pooled within‐treatment standard deviations from all other studies, provided that fewer than five studies had missing standard deviations. If more than five studies had missing standard deviations, we would have performed multiple imputation on the basis of the hierarchical model fitted to the non‐missing standard deviations. | We found no studies using the same scale that had missing standard deviations. Missing standard deviations could always be recovered from alternative statistical values or be obtained from the study authors. |

| Data synthesis | Had a trial reported more than one resilience scale, we planned to use the scale with better psychometric qualities (as specified in Appendix 3 in Helmreich 2017), to calculate effect sizes. | All studies measuring resilience only used one resilience scale. |

| If a study provided data from two instruments used equally in the included RCTs, two review authors (AK, IH) would have identified the appropriate measure through discussion (compare Storebø 2020). | This did not occur in this review. | |

| Network meta‐analyses (NMAs) would have been merely exploratory and would only have been conducted if the review results had a sufficient and adequate evidence base. Network meta‐analyses offer the possibility of comparing multiple treatments simultaneously (Caldwell 2005). They combine both direct (head‐to‐head) and indirect evidence (Caldwell 2005; Mills 2012), by using direct comparisons of interventions within RCTs, as well as indirect comparisons across trials, on the basis of a common reference group (e.g. an identical control group) (Li 2011). A network meta‐analysis on resilience‐training programmes does not exist. According to Mills 2012, Linde 2016 and the Cochrane Handbook (Chaimani 2019), there are three important conditions for the conduct of NMAs: transitivity, homogeneity, consistency. Had an NMA been possible, i.e. if the three conditions had been fulfilled, we would have conducted an analysis ‐ with expert statistical support as suggested by Cochrane (Chaimani 2019) ‐ using a frequentist approach in R (Rücker 2020; Viechtbauer 2010). For sensitivity analyses, we had planned to fit the same models using the restricted maximum likelihood method (Piepho 2012; Piepho 2014; Rücker 2020). We had intended to consider categorising resilience training into seven groups, based on the underlying training concept: (1) cognitive behavioural therapy, (2) acceptance and commitment therapy, (3) mindfulness‐based therapy, (4) attention and interpretation therapy, (5) problem‐solving therapy, (6) stress inoculation therapy and (7) multimodal resilience training. We may have included additional groups after conducting the full literature search. Reference groups that might have been included in the NMA were: attention control, wait‐list, treatment as usual or no intervention. We had planned to investigate inconsistency and flow of evidence in accordance with recommendations in the literature (e.g. Chaimani 2019; Dias 2010; König 2013; Krahn 2013; Krahn 2014; Lu 2006; Lumley 2002; Rücker 2020; Salanti 2008; White 2012b). |

The evidence base was insufficient to conduct a network meta‐analysis. | |

| Summary of findings | Depending on the assessment of heterogeneity and possible effect modifiers (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity), we would have created several ‘Summary of findings’ tables; for example, the clinical status of study populations or the comparator group. | We were not able to investigate potential effect modifiers for the primary outcomes in subgroup analyses and therefore created no additional ‘Summary of findings’ tables. |

| Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity | Where we detected substantial heterogeneity, we had planned to examine characteristics of studies that may be associated with this diversity (Deeks 2019). The selection of potential effect modifiers was based on experiences from previous reviews (Leppin 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016). We had intended to perform the following subgroup analyses on our primary outcomes, if we identified 10 or more studies during the review process (Deeks 2019):

|

For the primary outcomes at each time point, we identified fewer than 10 studies in a pair‐wise meta‐analysis. |

| Sensitivity analysis | Comparable with the planned subgroup analyses, we had planned to perform sensitivity analyses if more than 10 RCTs were included in a meta‐analysis. We had intended to restrict the sensitivity analyses to the primary outcomes.

For intervention studies assessing resilience with resilience scales, we had planned to perform a sensitivity analysis on the basis of the underlying concept (state versus trait) in these measures, and to limit the analysis to scales assessing resilience as an outcome of an intervention. To examine the impact of the risk of bias of included trials, we had intended to limit the studies included in the sensitivity analysis to those whose risk of bias was rated as low or unclear, and to exclude studies assessed at high risk of bias; for studies with low or unclear risk of bias, we had planned to conduct subgroup analyses. We had also intended to consider the restriction to registered studies. We had planned to identify registration, both by recording whether we found a study in a trial registry and by noting whether the study author claimed to have registered it. We had planned to perform sensitivity analyses by limiting analysis to those studies with low levels of missing data (less than 10% missing primary outcome). We had intended to limit the analysis to studies where missing data had been imputed or accounted for by fitting a model for longitudinal data, or where the proportion of missing primary outcome data was less than 10%. We had also intended to perform sensitivity analyses based on the ICC estimate in cluster‐randomised trials that had not adjusted for clustering, by excluding cluster‐RCTs where standard errors had not been corrected or corrected only on the basis of an externally‐estimated ICC. In an additional sensitivity analysis, we had planned to replace all externally‐estimated ICCs less than 0.10 by 0.10. Finally, we had intended to conduct a sensitivity analysis based on the unit of randomisation, by limiting the analysis to individually randomised trials. |

For the primary outcomes at each time point, we identified fewer than 10 studies in a pair‐wise meta‐analysis. |

This table provides details of analyses that had been planned and described in the protocol (Helmreich 2017), including revisions made at review stage, but were not used as they were not required or not feasible.

ACT: acceptance and commitment therapy; AIT: attention and interpretation therapy; CBT: cognitive‐behavioural therapy; RCT(s): randomised controlled trial(s); TAU: treatment as usual; vs: versus

Selection of studies

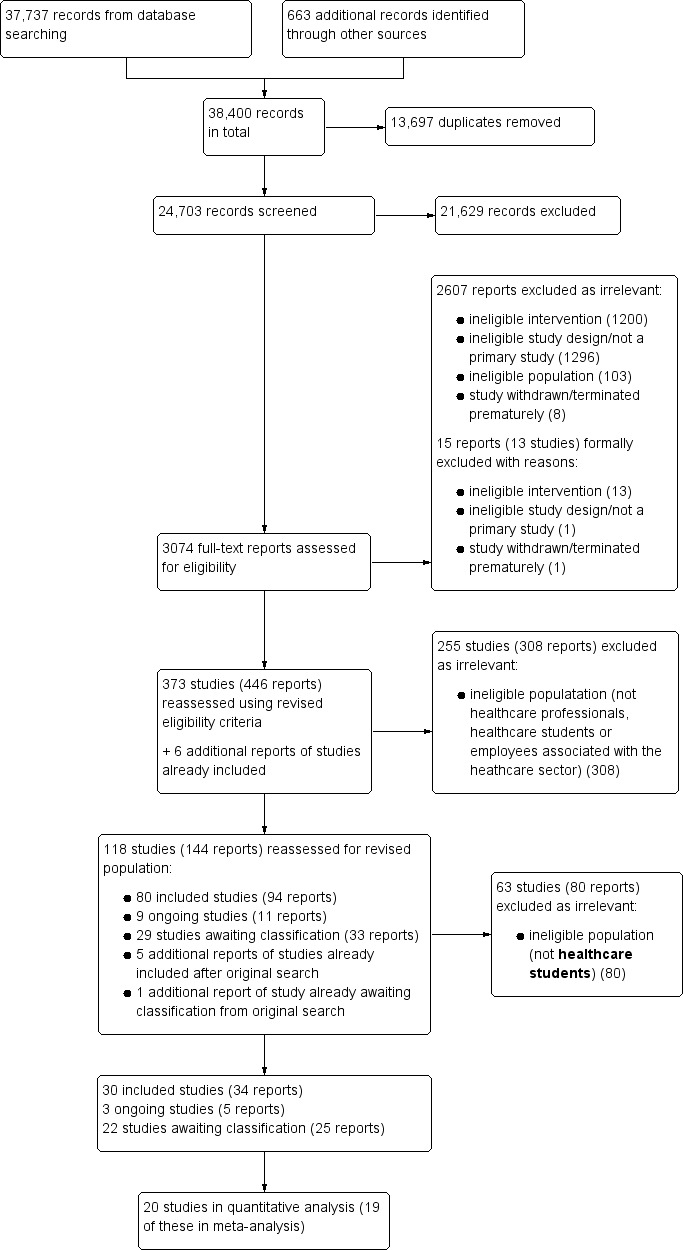

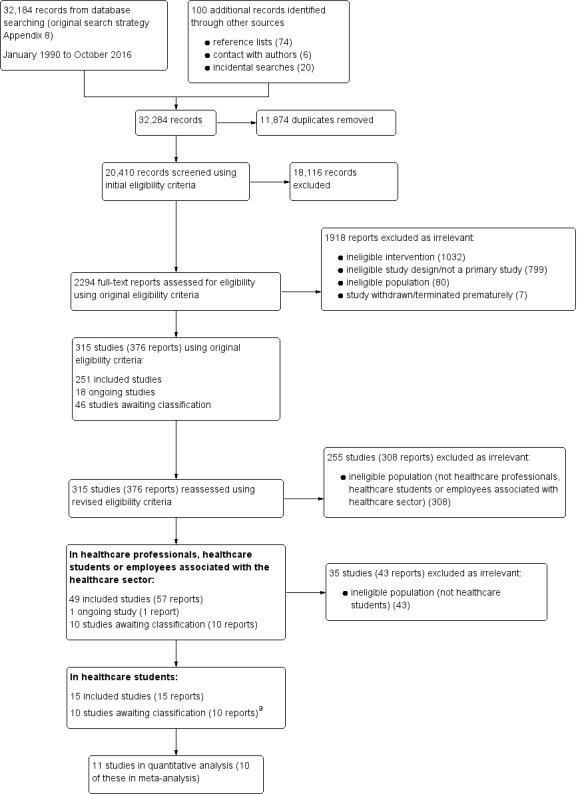

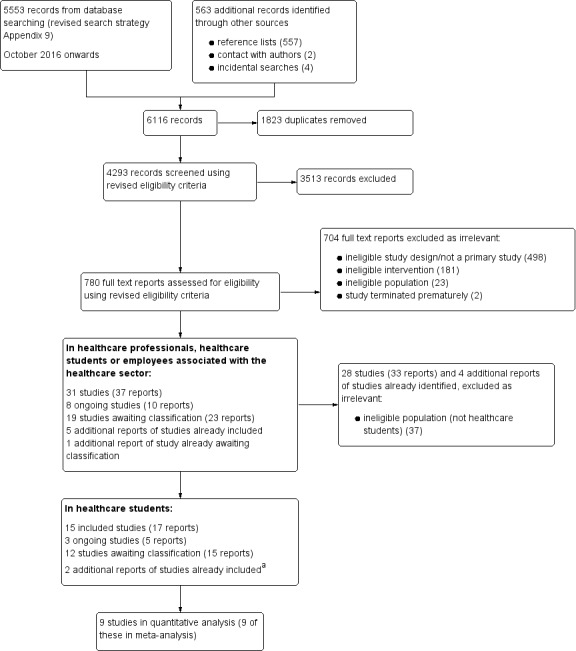

Two review authors (AK, IH) independently screened titles and abstracts in order to determine eligible studies. We immediately excluded clearly irrelevant papers. At full text level, the same two review authors (AK, IH), working independently, inspected for eligibility in duplicate. We calculated inter‐rater reliability at both stages (title and abstract screening and full text screening), resolving any disagreements in study selection by discussion. Where we could reach no consensus, a third review author (AC or KL) arbitrated. If necessary, we contacted the study authors to seek additional information. We recorded all decisions in a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009).

We assessed the feasibility of the selection criteria a priori, by screening 500 studies in order to attain acceptable inter‐rater reliability (see Differences between protocol and review). There was good agreement between the review authors (kappa = 0.72), and thus no need to refine or clarify the criteria. For scientific reasons, however, we adapted the eligibility criteria during review development (see Differences between protocol and review).

Data extraction and management

We developed a data extraction sheet (see Appendix 10), based on Cochrane guidelines (Li 2019), and tested it on 10 randomly‐selected included studies. This initial test resulted in sufficient agreement between the review authors. For each included study, two review authors (AK, IH) independently extracted the data in duplicate. The extraction sheet contained the following elements:

source and eligibility;

study methods (e.g. design);

allocation process;

participant characteristics;

interventions and comparators;

outcomes and assessment instruments (means and standard deviations (SDs) in any standardised scale);

results;

miscellaneous aspects.

We resolved any disagreements in data collection by discussion. Where we could reach no consensus, a third review author (AC or KL) arbitrated. If necessary, we contacted the study authors to seek additional information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AK, IH) independently assessed the risks of bias of the included studies. We checked the risk of bias for each study using the criteria presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, hereafter referred to as the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011a) (see Appendix 11). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by consulting a third review author (AC or KL). In accordance with Cochrane’s 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011b), we critically assessed each study across the following domains:

sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

selective outcome reporting (reporting bias).

We also considered the baseline comparability between study conditions as part of selection bias (random‐sequence generation), which is not defined in the Cochrane Handbook. In the first part of the assessment, we described what was reported to have happened in the study for each domain, before assigning a judgement for the risk of bias (low, high or unclear) for the entry.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We did not need to use our preplanned methods for analysing dichotomous outcomes (Helmreich 2017), as none of the included studies reported relevant dichotomous data for any of the prespecified primary or secondary outcomes.

Continuous data

Because the included resilience‐training studies used different measurement scales to assess resilience and related constructs (see Table 3; Table 4), we used standardised mean difference (SMD) effect sizes (Cohen's d) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous data in pair‐wise meta‐analyses. We calculated effect sizes on the basis of means, standard deviations (SDs) and sample sizes for each study condition. If the respective data were not provided, we computed Cohen's d from alternative statistics (e.g. t test, change scores). We assessed the magnitude of effect for continuous outcomes using the criteria for interpreting SMDs suggested in the Cochrane Handbook (Schünemann 2019a): a value of 0.2 indicates a small effect; 0.5 a moderate effect; and 0.8 a large effect (Cohen 1988b).

2. Primary outcomes: scales used.

| Outcomes | Number of studies | Studies and instruments |

| Resilience | 17 |

|

| Anxiety | 9 |

|

| Depression | 10 |

|

| Stress or stress perception | 13 |

|

| Well‐being or quality of life | 6 |

|

aFor depression, we preferred depression scales over burnout scales if both measures were reported. bConcerning Barry 2019, we included the values for the PSS‐10 in the pooled analysis, as this measure was used more often among the included studies.

3. Secondary outcomes: scales used.

| Outcomes | Number of studies | Studies and instruments |

| Social support (perceived) | 4 |

|

| Optimism | 4 |

|

| Self‐efficacy | 7 |

|

| Active coping | 2 |

|

| Self‐esteem | 2 |

|

| Hardiness | 1 |

|

| Positive emotions | 6 |

|

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

As the allocation of individuals to different conditions in resilience intervention studies partly occurs by groups (e.g. work sites, hospitals), we intended to include cluster‐randomised studies along with individually‐randomised studies. Since we identified no cluster‐RCTs, we only included individually‐randomised studies in meta‐analyses.

Repeated observations on participants

If there were longitudinal designs with repeated observations on participants, we defined several outcomes based on different follow‐up periods and conducted separate analyses, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2019b). One analysis included all studies with measurement at the end of intervention (post‐test), while other analyses were based on the period of follow‐up (short‐term: three months or less; medium‐term: more than three months to six months; and long‐term follow‐up: more than six months). We rated assessments as post‐intervention if performed within one week after the intervention. Assessments at more than one week after the intervention were counted as short‐term follow‐up.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

If selected studies contained two or more intervention groups, two review authors (AK, IH) determined which group was relevant to the review and the particular meta‐analysis, based on the inclusion criteria for interventions (see Types of interventions). For all studies that included several intervention groups, we considered only one intervention group as relevant for the review (see Results, specifically 'Interventions').

Dealing with missing data

In the case of studies where there were missing data, such as missing SDs, or where healthcare students had been combined with other participants, we contacted the original authors to enquire if the missing data or subgroup (summary outcome) data were available. To obtain missing summary outcome data for studies solely conducted in healthcare students, we contacted the study authors (at least twice) to request the respective data (i.e. means, SDs and sample sizes for the relevant study conditions, or alternative information to calculate the SMDs; see Measures of treatment effect).

We did not ask for individual‐level missing data for outcome data missing due to attrition, and performed no re‐analysis using imputation methods. We rated studies with high levels of missing data (≥ 10%) that used no imputation methods at high attrition risk of bias (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies). If the study authors had reported a complete‐case analysis as well as imputed data, we used the summary outcome data based on the imputed dataset (e.g. last observation carried forward (LOCF) in two studies, or ideally expectation maximisation or multiple imputation).

Following the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2019b), we computed missing SDs for continuous outcomes on the basis of other statistical information (e.g. t values, P values), since, as expected, we found enough information in all papers to restore SDs from the reported results.

Studies for which authors provided additional data not originally reported (e.g. number of participants analysed) are described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies tables. We recorded missing data and attrition levels for each included study in the ‘Risk of bias’ tables (beneath the Characteristics of included studies tables).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the presence of clinical heterogeneity by comparing study and population characteristics across all eligible studies, by generating descriptive statistics. In accordance with the Cochrane Handbook (Deeks 2019), we explored if studies were sufficiently homogeneous for participant characteristics, interventions and outcomes.

We assessed methodological diversity by inspecting the included studies for variability in study design and risks of bias (e.g. method of randomisation). In accordance with previous reviews that have already described the great heterogeneity in resilience intervention studies (Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016), we discuss the similarities and differences between the included studies for these study characteristics in the Results and Discussion sections.

To assess statistical heterogeneity between the included studies within each pair‐wise meta‐analysis (i.e. heterogeneity in observed treatment effects that exceeds sampling error alone), we relied on forest plots, Chi2 test, tau2, and I2 statistic, as suggested by Deeks 2019. We also considered G2, in order to take small‐study effects into account (Rücker 2011). Significant statistical heterogeneity is indicated by a P value in the Chi2 test lower than 0.10. Since resilience‐training studies are often conducted with relatively small sample sizes (e.g. Loprinzi 2011; Sood 2014), we acknowledge that the Chi2 test has only limited power in such cases. Tau2 also provides an estimate of between‐study variance in a random‐effects meta‐analysis. The I2 is a descriptive statistic, which reflects the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than to chance. In accordance with guidelines (Deeks 2019), we assumed non‐important heterogeneity for I2 values of 0% to 40%, moderate heterogeneity for I2 values of 30% to 60%, substantial heterogeneity for I2 values of 50% to 90%, and considerable heterogeneity for I2 values between 75% and 100%. G2 indicates the proportion of unexplained variance, having allowed for possible small‐study effects (Rücker 2011). No statistical heterogeneity is indicated by a G2 near zero. We also calculated the 95% prediction intervals from random‐effects meta‐analyses (see Data synthesis; pooled analyses with more than two studies) to present the extent of between‐study variation (Deeks 2019).

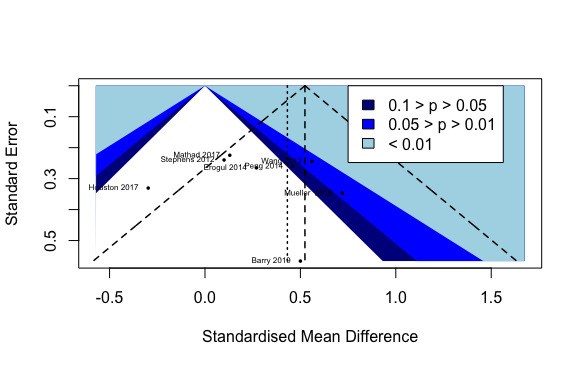

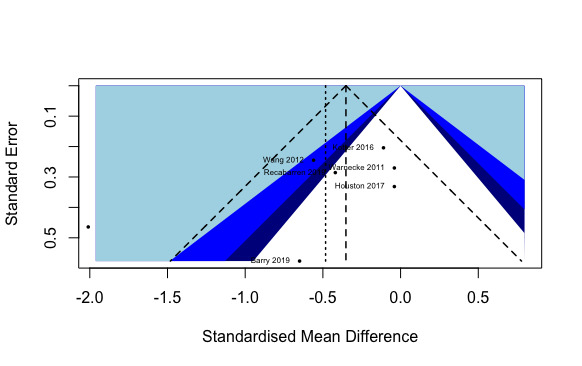

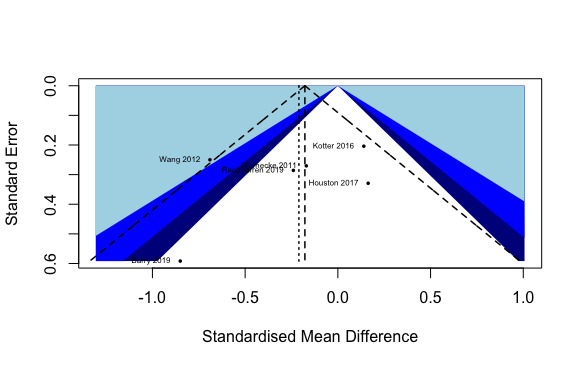

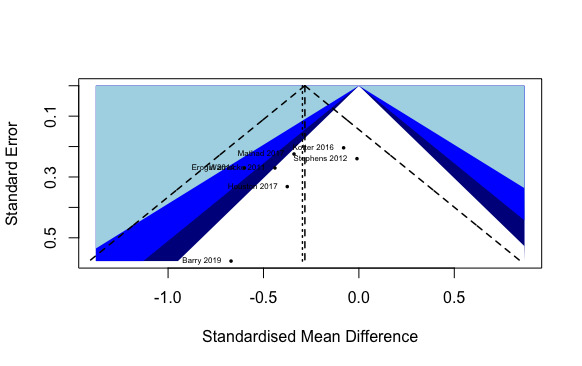

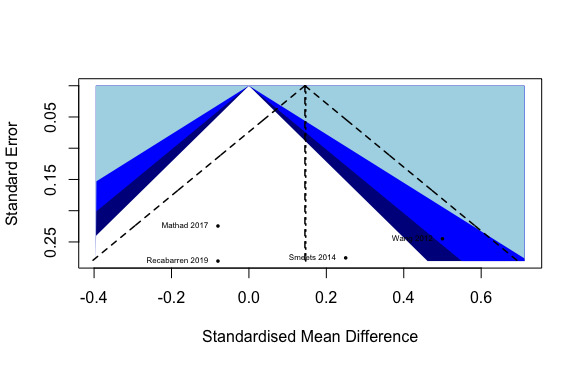

Assessment of reporting biases

We produced (contour‐enhanced) funnel plots for the primary outcomes at post‐test, plotting the effect estimates of studies against their standard errors on reversed scales (Page 2019; Peters 2008), in order to explore potential publication bias as part of our assessment of the certainty of the evidence and to create the 'Summary of findings' table (see Data synthesis). We considered the fact that funnel plot asymmetry does not necessarily reflect publication bias but can stem from a number of reasons (Page 2019). To differentiate between real asymmetry and chance, we followed the recommendations in Page 2019, and also used Egger’s test (regression test; Egger 1997) to test for funnel plot asymmetry.

We did not assess reporting bias as planned for the remaining outcomes at other time points (Helmreich 2017), due to an insufficient number of studies (fewer than 10 studies) included in the meta‐analyses for each outcome (see Effects of interventions).

Data synthesis

We synthesised the results, in narrative and tabular form, by describing the resilience interventions, their theoretical concept (when possible), as well as the populations and outcomes studied (see Results). We performed the statistical analyses either in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5; Review Manager 2014) or in R (R 3.6.3 2019; libraries used: meta (Balduzzi 2019) metafor (Viechtbauer 2010) and metasens (Schwarzer 2019), when appropriate.

We combined outcome measures of included studies through pair‐wise meta‐analyses (any resilience training versus control), in order to determine summary (pooled) intervention effects of resilience‐training programmes in healthcare students. The decision to summarise numerical results of RCTs in pair‐wise meta‐analyses depended on the number of studies found (at least two studies for a specific outcome and time point), as well as the homogeneity of the included studies by population (for age, sex), resilience interventions (i.e. comparable content and modalities), comparisons, outcomes measured (i.e. the same prespecified outcome, albeit with different assessment tools), and methodological quality (risk of bias) of selected studies. We conducted meta‐analyses where intervention studies did not differ excessively in their content, outcomes (measures) were not too diverse and there were no individual studies predominantly at high risk of bias.

For summary statistics for continuous data, we reported SMDs using an inverse variance random‐effects model. We used random‐effects pair‐wise meta‐analyses since we anticipated a certain degree of heterogeneity between studies, as indicated by the results of previous reviews (Joyce 2018; Leppin 2014; Macedo 2014; Robertson 2015; Vanhove 2016), and given the nature of the interventions included. We calculated the 95% prediction intervals from random‐effects meta‐analyses (see Assessment of heterogeneity). As part of our sensitivity analyses, we also performed fixed‐effect analyses (see Sensitivity analysis). We analysed continuous data reported as means and SDs in some studies separately from outcomes where SMDs and the respective standard error were taken from different data (e.g. independent t test). We subsequently combined these values using the generic invariance method in RevMan 5 (Review Manager 2014).

We also included studies with mixed samples (i.e. healthcare students and non‐healthcare students) in meta‐analyses, provided the subgroup data for healthcare students were reported separately or could be obtained from the study authors. If subgroup data were not available, we provided a narrative report of the findings of these studies in a separate section (see Effects of interventions, studies with mixed samples) for each outcome.

All studies measuring resilience used only one resilience scale. If a study reported more than one instrument for mental health and well‐being outcomes or for a specific resilience factor, we used the measure most often used among the included studies for effect size calculation. For the outcome of depression, we preferred depression scales over burnout scales if both measures were reported. Where studies reported both general measures of well‐being or quality of life and work‐related assessments (e.g. job satisfaction, work‐related vitality), we preferred general measures.

Once we had produced a summary of the evidence to date, and only if a pair‐wise meta‐analysis (any resilience training versus control) was possible, we examined whether the data were also suitable for a network meta‐analysis (NMA). There was insufficient evidence to perform a NMA.

Summary of findings

In this review, we used the software developed by the GRADE Working Group, GRADEpro: Guideline Development Tool (GRADEpro GDT), to create a 'Summary of findings' table for the comparison: resilience interventions versus control conditions for healthcare students.

We included all primary outcomes at post‐test in the ‘Summary of findings’ table. For each outcome, we assessed the certainty of the body of evidence using the GRADE approach proposed by the GRADE working group (Schünemann 2013; Schünemann 2019b), across the following five GRADE considerations:

limitations in the design and implementation of available studies (i.e. unclear or high risk of bias of studies contributing to the respective outcome; Guyatt 2011a);

high probability of publication bias (i.e. high risk of selective outcome reporting bias for studies contributing to the outcome, based on funnel plot asymmetry, Egger's test, different results of published versus unpublished studies, and whether the evidence consisted of many small studies with potential conflicts of interest) (Guyatt 2011b);

imprecision of results (i.e. small number of participants included in an outcome and wide CIs; Guyatt 2011c);

unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results (i.e. heterogeneity based on variation of effect estimates, CIs, the statistical test of heterogeneity and I2, but the subgroup analyses fail to identify a plausible explanation; Guyatt 2011d); and

indirectness of evidence (i.e. included studies limited to certain participants, intervention types, or comparators; Guyatt 2011e).

According to the GRADE system, meta‐analyses for continuous outcomes should include sample sizes of at least 400 participants for sufficient statistical precision. Where there was both substantial inconsistency (I2 ≥ 60%) for an outcome and imprecision, we did not downgrade for imprecision, as the heterogeneity might have influenced the CI (i.e. precision) and we did not wish to double‐downgrade for the same problem.

Two review authors (AK, IH), working independently, conducted the assessment of the certainty of the evidence in duplicate, resolving any disagreements by discussion or by consulting a third review author (AC, KL). We interpreted the magnitude of effect for continuous outcomes according to the criteria suggested in the Cochrane Handbook (Schünemann 2019a) (i.e. 0.2 as a small effect, 0.5 as a moderate effect, 0.8 as a large effect).

We rated the certainty of the evidence as high, moderate, low or very low (Schünemann 2013). High‐certainty evidence indicates high confidence that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of effect. Very‐low certainty evidence indicates that we have very little confidence in the effect estimate and that the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Due to the limited number of studies that we could include in our meta‐analyses for the primary outcomes (fewer than 10 studies; Deeks 2019), we were not able to conduct the planned subgroup analyses to examine key characteristics of studies that may be associated with the substantial heterogeneity detected for several outcomes (see Effects of interventions). We were also unable to perform a subgroup analysis for training intensity (post hoc addition).

Sensitivity analysis

Due to the limited number of studies we were able to include in our meta‐analyses for the primary outcomes (fewer than 10 studies; Deeks 2019), we did not conduct most of the planned sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the findings of this review.

However, for the primary outcomes at post‐test (i.e. the main analyses of this review), we performed the planned sensitivity analysis using a fixed‐effect model in addition to random‐effects meta‐analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We ran the first searches for this review in October 2016 according to the protocol (Helmreich 2017). We used the strategies in Appendix 8 to find studies in which the participants included any adults aged 18 years and older. Due to the large number of potentially eligible studies, we decided to split the review and changed the inclusion criteria to focus on healthcare sector workers and students (see Differences between protocol and review). Before running the top‐up searches in June 2019, we revised the original search strategy by limiting the population to healthcare sector workers and students (Appendix 9). Following these searches, we further revised the inclusion criteria to healthcare students only, which is the focus of this review.